Abstract

Objectives

To compare the differences in prevalence of antipsychotic and adjunctive pharmacotherapy use among individuals with schizophrenia between Sweden and Finland during 2006–2016.

Methods

Nationwide register-based data were utilized for constructing two separate cohorts: all persons in Finland with a diagnosis of schizophrenia treated in inpatient care during 1972–2014, and persons in Sweden aged 16–64 with recorded diagnoses of schizophrenia in inpatient or specialized outpatient care, sickness absence or disability pension during 2005–2013. The prevalence of use was assessed as a point prevalence on 31 October each year 2006–2016, based on drug use periods modelled with the PRE2DUP method. In 2016, the Finnish cohort included 37,780 persons and Swedish cohort 25,433 persons.

Results

The most commonly used antipsychotic in 2016 was oral olanzapine in both countries (22.7% [95% CI 21.6–22.4] in Finland, 20.9% [20.4–21.4] in Sweden), followed by clozapine which was more frequently used in Finland (22.0%, 21.6–22.4) than in Sweden (14.8%, 14.4–15.3). Long-acting injectable (LAI) use was almost two times more likely in Sweden (21.6%, 95% CI 21.1–22.1) than in Finland (12.8%, 12.5–13.1), a difference which was due to more common use of FG-LAIs in Sweden. A four-fold difference was observed in Z-drugs use (19.9% in Sweden versus 5.0% in Finland).

Conclusion

Potential explanations for the observed discrepancies include differences in national treatment guidelines, methods of data collection, patient characteristics and/or attitudes towards treatment among both patients and physicians.

Introduction

Antipsychotics represent the cornerstone of the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia [Citation1]. The physician’s choice to prescribe a pharmacological treatment to the individual patient is influenced by many different aspects [Citation2]. Apart from clinical guidelines, prescriber’s choice can also be influenced by culture [Citation3], personal attitudes toward, for example, antipsychotic polypharmacy or high-dose antipsychotic use [Citation2], views on whether to taper doses up slowly or go quickly for a good effect [Citation4], and perception of patient’s preference on the treatment, for example, which are tolerable side-effects [Citation5]. Genetics can also have an influence through population level pharmacogenetics (e.g. prevalence of ultra-rapid/ultra-slow metabolizers) [Citation6]. Previous studies have shown an overall transition from first-generation antipsychotics to second-generation ones which carry lower risk of serious adverse effects [Citation7]. Another trend in pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia is utilization of long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) to avoid problems caused by non-adherence, and benefits of LAI in relapse prevention [Citation8–10].

Antipsychotic utilization on a population-level varies between countries also with similar health care systems such as Sweden and Finland. A study covering the period 2005–2014 found 14.4 antipsychotic users per 1000 persons of all ages in Sweden compared to 33.2 users in Finland, which was the highest in the Nordic countries [Citation11]. These population-level prevalence differences may describe variations in prevalence of disorders which represent the main indications for antipsychotic use, namely schizophrenia and bipolar disorders, but could possibly also be due to variations in off-label use, medication costs, and overall willingness or ability for patients to access healthcare services. Previous studies have also noted some country-specific variations in the type of antipsychotics used. For instance, utilization of clozapine has been reported to be highest in the world in Finland, 189.2 users per 100,000 persons compared with, for example, 61.0 users in Sweden [Citation12]. However, overall use of psychotropic drugs is more similar between Sweden and Finland compared with, for example, Baltic countries [Citation13].

Very few studies have compared treatment choices and time trends of antipsychotics use among persons with schizophrenia between countries. Previous studies from Sweden and Finland found that olanzapine and risperidone are the two most often used antipsychotics in first-episode patients with schizophrenia [Citation14,Citation15]. However, these studies were conducted only for the period 2006–2007 in Sweden and 2000–2007 in Finland and thus, may not describe the current situation. In addition, trends in prevalence of LAI use, antipsychotic polypharmacy, or frequency of adjunctive pharmacotherapy use were not included in the analyses.

We aimed to compare the prevalence of antipsychotic use among all individuals with schizophrenia between Sweden and Finland. Separate analyses were performed for first-episode (incident) cases to determine which antipsychotics they used after their first diagnosis in outpatient care. In addition, we compared the prevalence of adjunctive pharmacotherapy with antidepressants, mood stabilizers and benzodiazepines and related drugs.

Methods

Study cohorts

This study investigates drug use patterns in two nationwide cohorts of individuals with schizophrenia, from Sweden and Finland. In both countries, all residents have been assigned a unique personal identification number which enabled linkage between nationwide registers.

The Finnish schizophrenia cohort included all persons with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder (International Classification of Diseases version 10, ICD-10 codes F20, F25; and ICD-9 and ICD-8 code 295*) during 1972-2014 in Finland [Citation16–18]. They were identified from the Hospital Discharge register (HDR) maintained by the National Institute of Health and Welfare, based on inpatient hospital care diagnoses. Data on all hospital care periods was derived from the HDR, purchased reimbursed medications from the Prescription register (maintained by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, SII) and dates of death from the SII database linked with the population register system. Data linkage from the registers was available up until the end of 2016. At the baseline for this study (31 October 2006), the cohort included 39,154 community-dwelling persons diagnosed with schizophrenia and the corresponding figure at the last measurement point (31 October 2016) was 37,780. Incident cases were defined as those who received their first diagnoses during 2006–2014, who had not used antipsychotic drugs for any indication at any dose during one year prior to their first recorded diagnosis of schizophrenia and initiated use of antipsychotic in outpatient care within one year after the diagnosis (N = 3856).

The Swedish schizophrenia cohort included all individuals aged 16–64 with at least one registered treatment contact with diagnoses of schizophrenia between 1 July 2005 until 31 December 2013 in Sweden [Citation9,Citation19]. Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder diagnoses (ICD-10 F20, F25) were derived from the following registers: the National Patient Register (NPR, maintained by the National Board of Health and Welfare) regarding inpatient and specialized outpatient care, and data on disability pension and sickness absence from the MiDAS register (maintained by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency). Data on all hospital care periods were derived from NPR, data on purchased medications since July 2005 was gathered from the Prescribed Drug Register (PDR, maintained by the National Board of Health and Welfare) and dates of death were obtained from the Causes of Death Register (maintained by the National Board of Health and Welfare). Demographic characteristics were based on data in the LISA register (maintained by Statistics Sweden). At the baseline for this study (31 October 2006), the cohort included 13,600 persons diagnosed with schizophrenia and the corresponding figure at the last measurement point (31 October 2016) was 25,433. The dataset was updated with follow-up data from the registers up until end of 2016. Information on measurements of clinical and sociodemographic factors for the Swedish and the Finnish cohort are given in . Incident cases were defined with similar inclusion/exclusion criteria as for the Finnish cohort and incident cases were diagnosed during 2006–2013 (N = 3145).

Table 1. Description of the Swedish (SWE) and Finnish (FIN) schizophrenia cohorts at 31 October 2016.

Hence, the two main differences between Finnish and Swedish cohorts are that Swedish cohort includes also persons diagnosed in outpatient care (versus only inpatient diagnoses in the Finnish cohort), and Swedish register includes all drug purchases whereas the Finnish one includes only reimbursed purchases.

Exposure

Antipsychotics were defined as the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code N05A (excluding lithium). Antipsychotics were further categorized into oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs), and into first generation (FG) and second generation (SG) antipsychotics (N05AE, N05AH, N05AX). Antipsychotic polypharmacy refers to concomitant use of two or more antipsychotics. “Any oral” refers to antipsychotics in oral formulation whereas “any LAI” means use of any LAI formulation. Other main exposure categories were antidepressants (ATC code N06A, with subcategories for tricyclic antidepressants TCAs ATC code N06AA, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors SSRIs ATC code N06AB, serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors SNRIs [venlafaxine N06AX16, milnacipran N06AX17 and duloxetine N06AX21]; and mirtazapine N06AX11), mood stabilizers (carbamazepine N03AF01, valproic acid N03AG01, lamotrigine N03AX09, lithium N05AN01), and benzodiazepines and related drugs (benzodiazepines N05BA, N05CD; and Z-drugs N05CF).

Modeling and analyses

The prevalence of use was assessed as a point prevalence on 31 October each year 2006–2016 when the data was available from both countries, based on drug use periods modelled with the PRE2DUP method [Citation20]. Each drug for each person was modelled separately, and also by separating oral and LAI formulations for each drug. The PRE2DUP method is based on the calculation of sliding averages of defined daily dose (DDDs) according to individual drug use patterns and it takes into account hospitalizations (when drugs are provided by the caring unit and not recorded in the registers), the stockpiling of drugs and changing dose. The method constructs drug use periods, that is, when drug use started and ended for each drug, which enables point prevalence assessment. This approach is crucial for assessment of polypharmacy, that is, whether two or more drugs are used concomitantly as this information cannot be directly obtained from drug dispensings. For prevalence of use at annual assessment points, users (numerator) were defined as those who had an ongoing use period at the assessment date, and the study population (denominator) included persons diagnosed with schizophrenia by the assessment date, who were alive and not hospitalized at this date. Thus, the number of persons included in the prevalence assessment point changed every year.

The analyses were conducted separately in the Finnish (FIN) and Swedish (SWE) cohorts. All analyses of specific drugs and drug categories (except antipsychotics, AP, polypharmacy) are conducted by reporting prevalence of use regardless of potential other medications used at the same time from the same class (i.e. prevalence estimates do not add up to 100%). Most common first antipsychotic drugs among persons with incident diagnoses of schizophrenia were analyzed within one year after the first diagnoses. Prevalence estimates (%) between the cohorts were compared with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated for percentages (non-overlapping CIs were considered statistically significant). Prevalence trends were calculated from the years 2006–2016 using linear regression.

As sensitivity analyses, data on electronic prescription (e-prescription) dispensings of BZDRs in 2016 was derived from Kanta, the Finnish electronic prescription database. Data from dispensed, non-reimbursed BZDRs from e-prescriptions were added to the Finnish Prescription register data, and utilized for determining prevalence of BZDR, benzodiazepine and Z-drug prevalence in 2016.

Ethical review

The Regional Ethics Board of Stockholm approved this research project (decision 2007/762–31) related to the Swedish data. Permissions were granted by pertinent institutional authorities at the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare (permission THL/847/5.05.00/2015), the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (65/522/2015), and Statistics Finland (TK53-1042-15).

Results

The Swedish cohort was younger (mean age 52.1 years compared to 56.3) and had a higher proportion of men than women (56.7%) whereas in the Finnish cohort both genders were equally represented in 2016 (). Persons with schizophrenia in the Finnish cohort had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease and previous cancer whereas substance abuse was diagnosed more often in the Swedish cohort.

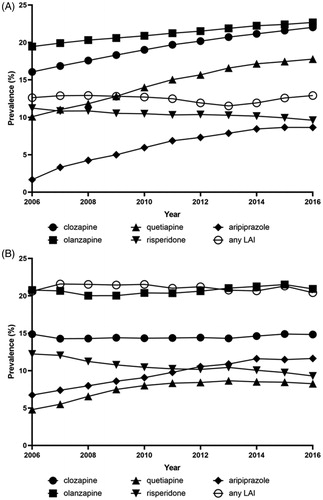

During the 11 years’ observation window on prevalence of specific antipsychotics used by persons with schizophrenia, many time-related trends in both cohorts were observed (). The prevalence of first-generation antipsychotics decreased in both countries whereas second-generation antipsychotics were used more frequently towards 2016. Some first-generation antipsychotics (such as chlorpromazine) disappeared from the market in both countries during the period whereas new antipsychotics (such as olanzapine LAI, paliperidone LAI, aripiprazole LAI) have been launched. In terms of most common SG oral antipsychotics, aripiprazole and quetiapine show increasing trends in both countries whereas risperidone use has decreased (). The most commonly used antipsychotic in 2016 was oral olanzapine in both countries (22.7% [95% CI 21.6–22.4] in Finland, 20.9% [20.4–21.4] in Sweden), followed by clozapine which was more frequently used in Finland (22.0%, 21.6–22.4) than in Sweden (14.8%, 14.4–15.3). Quetiapine was the third most common drug in Finland (17.8%, 17.4–18.2) and the fifth in Sweden (8.2%, 7.9–8.6). The third most common antipsychotic in Sweden was aripiprazole (11.6%, 11.2–12.0) which was the fifth most common in Finland (8.6%, 8.4–8.9). Risperidone oral was the fourth most common antipsychotic in both countries with a similar prevalence in both (9.6% [9.3–9.9] Finland, 9.3% [8.9–9.7] Sweden).

Figure 1. Point prevalence of most commonly used second generation oral antipsychotics and any long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) during 2006–2016 among persons with schizophrenia in Finland (A) and Sweden (B).

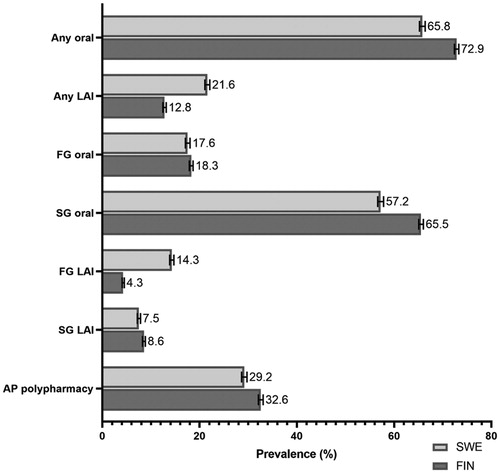

The overall point-prevalence of antipsychotic use in 2016 was 78.9% for Finland and 77.5% for Sweden. The use of LAIs was almost two times more common in Sweden (21.6%, 95% CI 21.1–22.1) than in Finland (12.8%, 12.5–13.1) in 2016 (). This difference was explained by more common use of FG-LAIs (14.3%, 13.9–14.7 in Sweden and 4.3%, 4.1–4.5 in Finland), whereas prevalence of SG-LAI use was more similar (7.5% (7.2–7.9) in Sweden and 8.6% (8.3–8.8) in Finland). Antipsychotic polypharmacy was somewhat more common in Finland (32.6%, 32.1–33.1) than in Sweden (29.2%, 28.6–29.8). In the Swedish sub-cohort of persons treated only in outpatient care and not hospitalized during the follow-up (2006–2016, n = 6154, 24.2%), the point prevalence of antipsychotic use was 68.5% and only 18.2% had antipsychotic polypharmacy. The sub-cohort used less clozapine (11%) and LAIs (9.3%) compared with the total cohort.

Figure 2. Prevalence of use (%) of specific antipsychotic drug classes in persons with schizophrenia in Finland (FIN) and Sweden (SWE) in 2016 (with 95% confidence intervals). Each category is assessed separately regardless of other categories potentially used at the same time (i.e. percentages do not add up to 100%). LAI: long-acting injectable antipsychotic; FG: first-generation; SG: second-generation; AP polypharmacy: concomitant use of ≥2 antipsychotics.

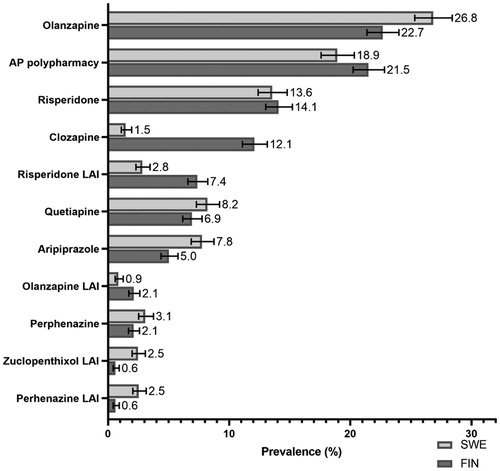

Olanzapine was the most commonly used first antipsychotic as monotherapy in outpatient care among persons with first-episode schizophrenia in Sweden (26.8%, 95% CI 25.3–28.4) and Finland (22.7%, 21.2–24.8) (), followed by risperidone. Antipsychotic polypharmacy was highly prevalent both in Swedish (18.9%, 17.6–20.3) and in Finnish first-episode patients (21.5%, 18.2–21.6), whereas clozapine use was much higher in Finland (12.1% [12.2–15.2] than in Sweden (1.5% [1.1–2.0]). Of the two-drug combinations, olanzapine–aripiprazole was the most common combination among two-drug users in Sweden (15.3%, 12.5–18.6) and the second most common in Finland (11.4%, 8.9–15.3) whereas clozapine–aripiprazole was the most common combination in Finland (14.7%, 11.3–18.8), but rarely used in Sweden (1.7%, 0.9–3.2). Other two-drug combinations were mainly combinations of second-generation oral antipsychotics.

Figure 3. Prevalence of most common first antipsychotic drugs used in outpatient care among persons with incident diagnoses of schizophrenia in Finland (FIN) and Sweden (SWE). Calculated proportions from those who initiated some antipsychotic within one year after their first diagnoses (SWE, N = 3145, FIN, N = 3856). LAI: long-acting injectable antipsychotic; AP polypharmacy: concomitant use of ≥2 antipsychotics.

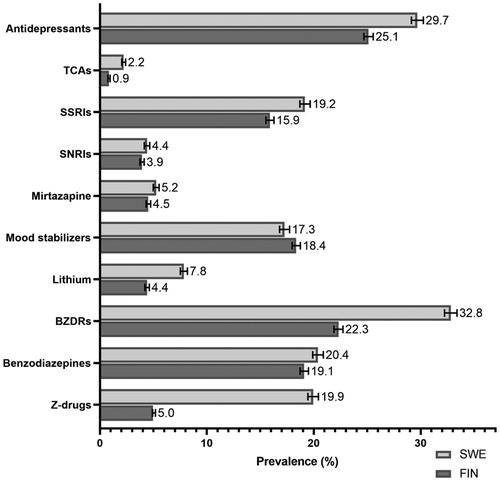

Antidepressants were more commonly used as adjunctive pharmacotherapy in Sweden (29.7%, 95% CI 29.1–30.3) than in Finland (25.1%, 24.7–25.6) (). SSRIs were the most commonly antidepressant class in both countries. Prevalence of mood stabilizer use was quite similar in Finland (18.4%, 18.0–18.8) and in Sweden (17.3%, 16.8–17.7). However, lithium use was almost two times more frequent in Sweden (7.8%, 7.5–8.2) than in Finland (4.4%, 4.2–4.6). Large differences were noticed in the use of benzodiazepine and related drugs, as shown by an almost four-fold higher use of Z-drugs in Sweden (19.9%, 19.5–20.4) than in Finland (5.0%, 4.8–5.2). In the sensitivity analyses with additional dispensing data from e-prescriptions, the prevalence of BZDR use in 2016 in Finland increased (from 22.3% to 28.4%). This was caused by increased prevalence of benzodiazepines use (from 19.1% to 25.3%) whereas prevalence of Z-drug use remained on a similar level (5.0–5.2%).

Figure 4. Prevalence of adjunctive pharmacotherapies in persons with schizophrenia in Finland (FIN) and Sweden (SWE) in 2016. TCAs: tricyclic antidepressants; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRIs: selective serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors; BZDRs: benzodiazepines and related drugs (so-called Z-drugs).

Antidepressant, benzodiazepine and Z-drug use were more common among persons with antipsychotic polypharmacy than among those with antipsychotic monotherapy in both cohorts ().

Table 2. Prevalence of adjunctive pharmacotherapy use compared between antipsychotic (AP) monotherapy and polytherapy users in 2016, in Finnish and Swedish cohorts.

In the Swedish sub-cohort of persons ever hospitalized due to schizophrenia (n = 19,279), the observed differences compared with the Finnish cohort remained similar (clozapine was less often used [16.1%, 15.6–16.6] in the Swedish cohort than in the Finnish cohort [22.0%, 21.6–22.4]), or were further accentuated: LAIs use was two times more likely in the Swedish cohort (25.5% versus 12.8%) and the difference was due to more frequent use of FG-LAIs in Sweden (16.4% versus 4.3%). In addition, Z-drugs were used by 21.1% of the ‘ever-hospitalized Swedish cohort’ (versus 5.0% of the Finnish cohort).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the most thorough comparison to date of treatment patterns of persons with schizophrenia between two countries. According to our data, the prevalence of antipsychotic use among schizophrenia patients in Finland and Sweden was similar, although overall use of antipsychotics in the general population has been shown to be markedly higher in Finland [Citation10]. The biggest differences were seen in the overall use of LAIs and clozapine, with LAIs being used more in Sweden and clozapine in Finland, and the more prominent use of adjunctive medications, especially Z-drugs in Sweden. Incidentally these are three topics that often rise up for debate in clinical practice and which are often found inconsistently covered or recommended in clinical care guidelines. In line with previous studies, olanzapine and risperidone are the most frequently used antipsychotics among first-episode patients in Sweden and in Finland [Citation14,Citation15], although we found that antipsychotic polypharmacy has surpassed risperidone use in both countries. Similar trend from FGA to SGA was observed in both countries as expected.

There may be multiple reasons for the higher level of adjunctive medication (antidepressants, benzodiazepines, Z-drugs) usage in Sweden compared to Finland. It could be either due to Swedish patients having more psychiatric comorbidities, such as affective or anxiety disorders, or that these disorders are more readily discovered and treated. A previous report by Suokas et al. has shown that antidepressant use is associated with a reduced and benzodiazepine use with an increased risk of antipsychotic polypharmacy especially in chronic schizophrenia patients [Citation21]. Our results also showed more antipsychotic polypharmacy in Finland, where antidepressants are used less, even though benzodiazepine use was less frequent in Finland than in Sweden. However, in both countries antipsychotic polypharmacy was associated with a higher prevalence of antidepressant, benzodiazepine and Z-drug use than monotherapy, indicating that the overall prevalence of adjunctive medication use is higher in Sweden and is not explained by the level of antipsychotic polypharmacy utilization. One potential explanation for the markedly higher level of benzodiazepine and related drug use in Sweden could be the higher frequency of substance abuse disorder comorbidities seen in the Swedish cohort, as these patients are sometimes prescribed such drugs, even though their use may have detrimental consequences [Citation22]. Taken together, the levels of adjunctive medication use both in Sweden and Finland were generally higher than what has previously been described for other countries. A recent study from Asia from the REAP survey in 2016 revealed that 12% of schizophrenia patients were prescribed adjunctive antidepressants, 14% mood stabilizers and 28% benzodiazepines [Citation23], and a German inpatient study among 30,908 schizophrenia patients between 2000 and 2015 reported 32% of the patients having been prescribed conjunctive tranquilizers, 17% antidepressants, 14% anticonvulsants, 2% lithium and 8% hypnotics [Citation24].

With regard to the choice of antipsychotics, differences on how national care guidelines are formulated are likely to have an impact on prescription patterns. In Sweden, the 2014 national guidelines recommended clozapine for treatment resistant patients and patients with suicidal behavior [Citation25]. LAI treatment was recommended for patients who prefer this, or repeatedly drop out of treatment. Risperidone and flupentixol were given almost equal priority among LAIs, whereas olanzapine was given very low priority. In Finland, the guidelines state that medication choices should be made individually and do not give a clear prioritization between antipsychotics, other than stating that clozapine is more effective than the others, but should only be considered after two failed trials with other antipsychotic medications due to risk of agranulocytosis [Citation26]. The guidelines also state that long-acting injection formulations may be useful for anosognostic patients and might improve long-term treatment results for all patients. One possible interpretation is that patients who are treatment resistant, or difficult to treat because of other reasons were more readily prescribed LAI in Sweden (with FG more prominent due to differences in cost), and clozapine in Finland.

However, the observed differences cannot be solely attributed to discrepancies between national guidelines. The results provided here may imply that prescribers are influenced by more recent observational studies showing better comparative effectiveness of clozapine, LAIs and polypharmacy over antipsychotic monotherapy [Citation9,Citation16,Citation18]. However, recent observational evidence also ill-favors the use of benzodiazepines and their derivatives [Citation27], but the results show that those were still widely used in both countries, although more prominently in Sweden.

Antipsychotic polypharmacy was relatively common in this study, 33% and 29% of prevalent cohorts in 2016 in Sweden and Finland, respectively. Antipsychotic polypharmacy also was the second most common choice among first-episode patients, with one quarter of patients initiating antipsychotic use in outpatient care with more than one antipsychotic concurrently. In previous studies, higher prevalences on antipsychotic polypharmacy have been reported from Asia [Citation23]. The Finnish guidelines state that monotherapy should be strived for whenever possible and more than two antipsychotics should not be used at the same time [Citation26], and polypharmacy is not part of the recommended treatment in the Swedish guidelines [Citation25]. The Finnish guidelines also advocate against using per oral antipsychotic medications in addition to long-acting injectables. Although not in line with guidelines in Sweden and Finland, frequent use of antipsychotic polypharmacy may not be a safety concern as recent observational studies have shown that antipsychotic polypharmacy does not increase risk of physical morbidity or mortality in schizophrenia [Citation28].

Strengths and limitations

Overall, the strengths of this study are based on using comprehensive data from nationwide cohorts including all persons with diagnosed schizophrenia and their medication use over an extensive 11-year follow-up period. However, some differences in the registers utilized between the countries exist, which may have influenced our results. The Swedish cohort may include less severe cases as diagnoses were also collected from specialized outpatient care, sickness absence and disability pension registers, whereas the Finnish cohort included only persons treated in inpatient care. The sub-cohort treated only in outpatient care used antipsychotics less often in general, and less often antipsychotic polypharmacy, LAIs and clozapine, although this was only a minority of the total Swedish cohort.

The Swedish Prescription register records all dispensings, whereas the Finnish one only reimbursed dispensings. This is one potential explanation for some of the higher prevalences in Sweden, especially related to benzodiazepines and related drugs, as these are restrictively reimbursed in Finland. For example, temazepam is an often-used hypnotic in Finland, but in 2016, it was not reimbursed at all and, thus, is lacking from Finnish prevalence estimates. In addition, some small packages of Z-drugs were not reimbursed in 2016 in Finland. However, by using additional data from e-prescription dispensings in 2016 (e-prescriptions covered 94% of all drug dispensings in Finland in 2016), we showed that difference in Z-drug use is not caused by use of non-reimbursed packages as Z-drug prevalence remained on the same level whereas benzodiazepine use prevalence increased. Thus, methodological or data source-related differences do not explain this finding.

Conclusions

In conclusion, although prescription patterns of antipsychotics were largely similar between countries, LAIs and clozapine are used differently in Sweden and Finland, and adjunctive pharmacotherapy is more prevalent in Sweden. Some of the discrepancies may be explained by differences in national treatment guidelines, but they also may reflect differences in patient characteristics and/or attitudes towards treatment among both patients and physicians.

Acknowledgements

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding authors had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Authors’ contribution

Concept and design: J. T., H. T., and A. T.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: H. T., M. L., and S. C.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: H. T. and A. P.

Obtained funding: H. T. and J. T.

Supplementary_Table.docx

Download MS Word (19.8 KB)Disclosure statement

Jari Tiihonen, Heidi Taipale, Ellenor Mittendorfer-Rutz and Antti Tanskanen have participated in research projects funded by grants from Janssen-Cilag and Eli Lilly to their employing institution. Heidi Taipale reports personal fees from Janssen-Cilag. Jari Tiihonen reports personal fees from the Finnish Medicines Agency (Fimea), European Medicines Agency (EMA), Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, and Otsuka; is a member of advisory board for Lundbeck, and has received grants from the Stanley Foundation and Sigrid Jusélius Foundation. Markku Lähteenvuo is a board member of Genomi Solutions Ltd., has received honoraria from Sunovion Ltd., Orion Pharma Ltd., and Janssen-Cilag Ltd., and research funding from The Finnish Medical Foundation and Emil Aaltonen Foundation. Simon Cervenka has received grant support from AstraZeneca as a coinvestigator and has served as a speaker for Otsuka.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barnes TRE. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567–620.

- Latimer EA, Naidu A, Moodie EEM, et al. Variation in long-term antipsychotic polypharmacy and high-dose prescribing across physicians and hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1210–1217.

- Ng CH, Klimidis S. Cultural factors and the use of psychotropic medications. In: Ng C, Singh B, Chiu E, editors. Ethno-psychopharmacology: advances in current practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008. p. 123–134.

- Best-Shaw L, Gudbrandsen M, Nagar J, et al. Psychiatrists' perspectives on antipsychotic dose and the role of plasma concentration therapeutic drug monitoring. Ther Drug Monit. 2014;36(4):486–493.

- Helbling J, Ajdacic-Gross V, Lauber C, et al. Attitudes to antipsychotic drugs and their side effects: a comparison between general practitioners and the general population. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6(1):42.

- Eum S, Lee AM, Bishop JR. Pharmacogenetic tests for antipsychotic medications: clinical implications and considerations. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18(3):323–337.

- Carbon M, Kane JM, Leucht S, et al. Tardive dyskinesia risk with first- and second-generation antipsychotics in comparative randomized controlled trials: a meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):330–340.

- Kane JM. Treatment strategies to prevent relapse and encourage remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:27–30.

- Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):686–693.

- Taylor DM, Velaga S, Werneke U. Reducing the stigma of long acting injectable antipsychotics - current concepts and future developments. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(Sup1):S36–S39.

- Halfdanarson Ó, Zoega H, Aagaard L, et al. International trends in antipsychotic use: study in 16 countries, 2005–2014. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27(10):1064–1076.

- Bachmann CJ, Aagaard L, Bernardo M, et al. International trends in clozapine use: a study in 17 countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136(1):37–51.

- Harro J, Aadamsoo K, Rootslane L, et al. Comparison of psychotropic medication use in the Baltic countries. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74(4):301–306.

- Tiihonen J, Haukka J, Taylor M, et al. A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):603–609.

- Reutfors J, Brandt L, Stephansson O, et al. Antipsychotic prescription filling in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(6):759–765.

- Taipale H, Mehtala J, Tanskanen A, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs for rehospitalization in schizophrenia-a nationwide study with 20-year follow-up. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1381–1387.

- Tiihonen J, Tanskanen A, Taipale H. 20-Year nationwide follow-up study on discontinuation of antipsychotic treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):765–773.

- Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Mehtala J, et al. Association of antipsychotic polypharmacy vs monotherapy with psychiatric rehospitalization among adults with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(5):499–507.

- Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274–280.

- Tanskanen A, Taipale H, Koponen M, et al. From prescription drug purchases to drug use periods – a second generation method (PRE2DUP). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:21.

- Suokas JT, Suvisaari JM, Haukka J, et al. Description of long-term polypharmacy among schizophrenia outpatients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48(4):631–638.

- Votaw VR, Geyer R, Rieselbach MM, McHugh RK. The epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;200:95–114.

- Dong M, Zeng L-N, Zhang Q, et al. Prescription of antipsychotic and concomitant medications for adult Asian schizophrenia patients: findings of the 2016 Research on Asian Psychotropic Prescription Patterns (REAP) survey. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;45:74–80.

- Toto S, Grohmann R, Bleich S, et al. Psychopharmacological treatment of schizophrenia over time in 30 908 inpatients: data from the AMSP study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;22(9):560–573.

- SOCIALSTYRELSEN. Nationella riktlinjer för antipsykotisk läkemedelsbehandling vid schizofreni och schizofreniliknande tillstånd. Artik. 2014-4-6. 2014. Available from: www.socialstyrelsen.se.

- Duodecim FMS. Current care guideline on schizophrenia. Published Online First: 2015. Available from: http://www.kaypahoito.fi/.

- Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Torniainen M, et al. Mortality and cumulative exposure to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and benzodiazepines in patients with schizophrenia: an observational follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):600–606.

- Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Mehtala J, et al. 20-Year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):61–68.