Abstract

Background

Sexual abuse is associated with severe health consequences, and the European Union has, through the Istanbul Convention, urged its member countries to provide specialist care for victims of sexual abuse.

Aim

This aim of this study was to investigate patient- and abuse-related characteristics among patients seeking help at a specialist clinic in Sweden, with focus on disclosure, mental health and appropriate healthcare access.

Methods

This is a descriptive study where journal data from 100 consecutive patients January 2017 to February 2018 were analyzed. All adult individuals (women n = 80, men n = 8) who had taken part in the standardized semi-structured intake interview at the clinic were included (n = 88).

Results

At admission, mean age was 40.3 (SD 11.9), mean number of psychiatric diagnoses 6.3 (2.6), and 93% of the patients scored above cut-off (≥34) on IES-R for PTSD. A majority of the patients (87%) had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse (CSA), and mean time to first disclosure was 15.9 (SD 15.3) years. In total, 82% of the patients had, despite disclosure, experienced difficulties accessing appropriate healthcare before coming to the specialist clinic.

Conclusion

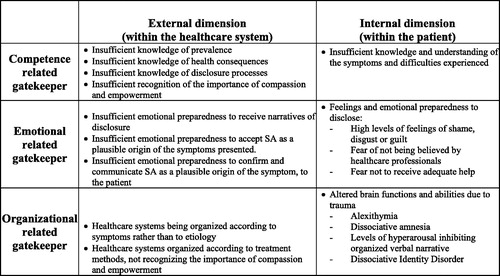

Adult victims of sexual abuse have difficulties accessing appropriate healthcare. This constitutes a gender-based equality problem. A model of gatekeeping mechanisms with two dimensions (external and internal) and three categories (Competence related, Organizational and Emotional) is proposed to understand these difficulties.

Introduction

The high prevalence of sexual abuse (including sexual violence, rape, assault and other types of violation of an individual’s sexual integrity), its severe health consequences with high risk for multiple diagnosis and suicide attempts [Citation1–4] as well as re-victimization and further traumatization after sexual abuse [Citation5–9], makes access to appropriate healthcare for victims of sexual abuse important. Disclosure has been described as the start of the process of healing [Citation10], but sexual abuse, child sexual abuse (CSA) in particular, is associated with disclosure barriers and delay, often for many years [Citation11–14]. Collin-Vezina et al. have described an ecological framework of three barrier categories explaining the process of disclosure: barriers from within (including abilities and feelings within the victim), barriers in relation to others (including family and network support or dysfunctions), and barriers in relation to the social world (including sexuality taboos and lack of services).

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched guidelines for healthcare for victims of sexual abuse, stating ‘…In most countries, however, there is a gap between the health care needs of victims of sexual violence and the existing level of health services provided’ [Citation15], and later defined sexual violence as a serious public health threat and human rights problem [Citation16]. The European Union, through the Istanbul Convention, has urged member countries to provide specialist care to victims of sexual violence (Europe, Istanbul, 11/05/2011 [Citation17]). However, in many parts of Europe there are still no specific clinics, research programs, or coordination of healthcare for victims of sexual abuse. In Sweden, there are two public emergency services for victims of rape and one public specialist clinic with the capacity to provide non-emergency healthcare for approximately 80 adults victims of sexual abuse per year. Alongside with the public healthcare, there is also a non-governmental non-profit organization running a non-emergency specialist clinic for victims of sexual abuse. In the national health guide (www.1177.se), victims of sexual abuse in need of healthcare are encouraged to ask for help within the primary healthcare system. However, in 2020, The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKR) confirmed a still existing gap between the healthcare needs of victims of sexual abuse and the healthcare availability and accessibility [Citation18]. To bridge that gap, more information about the patient group is needed. This aim of this study was to investigate patient- and abuse-related characteristics among patients seeking help at a specialist clinic in Sweden, with focus on disclosure, mental health and appropriate healthcare access.

Method

Clinical setting

In this descriptive study, data were collected from the specialist clinic run by the non-governmental nonprofit organization WONSA. The clinic was chosen since it is the only non-emergency specialist clinic with systematic data collection of abuse related characteristics in Sweden. The clinic is situated in Stockholm, but patients from all over the country are accepted. In 2017, two doctors specialized in Family Medicine and 20 therapists – psychologists, psychotherapists, physiotherapists and body therapists – worked at the clinic. Patients generally find their way to the clinic through internet search, networks of support organizations, or via referrals from other healthcare services. The specialist clinic is funded to 90% by donations and volunteering staff, and due to lack of resources, only patients who are fluent in Swedish, Spanish or English can be assessed and treated at the clinic for the moment.

Data collection

In order to facilitate and structure the patient narratives and records, a standardized semi-structured intake interview is used at admission to the clinic (supplementary material). The questions in the intake interview were initially chosen either because the data collected by the questions were assumed, or known, to impact or indicate health outcome, such as age at onset of abuse, duration of period of abuse, type of abuse, relation to perpetrator, and number of perpetrators. Number and types of diagnoses, given earlier or at admission to the clinic, as well as present or earlier suicidal thoughts or actions were also collected. Due to intermittent emotional stress or memory failure during the intake interview, all included patients did not answer all the questions.

Three standardized questionnaires were used in conjunction with the interview:

We assessed number of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), as identified in the American ACE-study, with well-documented impact on health outcomes [Citation19,Citation20]. Each of the ACEs gives one score, on a scale between 0 and 10.

We used the Impact of Event Scale Revised (IES-R) to assess posttraumatic stress symptoms. The IES-R has shown high internal consistency and the correlation between the IES-R and the PTSD-checklist (PCL5) has been shown to be high [Citation21,Citation22]. A cut-off for PTSD at 34 points has provided good sensitivity (0.86 and 0.89 respectively n = 854 and n = 3313) in large studies [Citation22,Citation23].

We assessed depressive symptoms with the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Scale – Self-rating (MADRS-S), a self-rating instrument with high diagnostic sensitivity (87.4%) and significant association with the M.I.N.I., as an instrument for assessing depression [Citation24].

The answers to the semi-structured patient interview were used to produce group level data on selected patient characteristics. The items related to perpetrators refer to the first assault and the first perpetrator, although many had been subjected to multiple abuse or abuse by several perpetrators. Sexual abuse duration and disclosure delay was measured by the time between the first and the last abuse occasion and disclosure, respectively. Suicidality was measured by asking whether suicidal thoughts or attempts had ever occurred. If they had occurred, the patient was asked to confirm whether the intention had been to hurt oneself (self-destructive action) or if the intention had been to commit suicide (suicide attempt). The patient was also asked how many times they had self-harmed/attempted suicide, and age at first occasion. Three different types of abuse were defined: type 1 – abuse without physical contact; type 2 – abuse with physical contact but without penetration; type 3 – abuse with penetration. Finally, the patients were also asked whether they had tried to get access to healthcare because of symptoms related to sexual abuse within the private or public healthcare system available in Sweden, before seeking help at the specialist clinic. If so, they were asked whether they had disclosed their exposure of sexual abuse when asking for healthcare. Only those who had disclosed when asking for healthcare, were categorized as ‘Attempted to access appropriate healthcare before coming to the specialist clinic’ ().

Table 1. Healthcare seeking and disclosure data.

Included patients

Journal records from 100 consecutive patient intake visits, between 1 January 2017 and 28 February 2018, were reviewed. Among these patients, the standardized semi-structured intake interview could not be used for 11 patients, because of too high emotional stress during the intake visit, and one patient being a child (8 years old). Among the remaining 88 patients included in the analysis, a majority were women (n = 80). Mean age at inclusion was 40.31 years (SD 11.9) and 72% had taken part of professional or university studies (). All patients were Swedish speaking.

Table 2. Data on participants and abuse characteristics.

Statistical method

Basic statistics were used to summarize the data. Since the data collected were chosen because assumed, or known, to impact or indicate health outcome, we wanted to test the correlation between collected patient and abuse specific data and health outcome such as number of diagnoses and prevalence of suicide attempts for example. Spearman’s correlations tests were used to test unadjusted associations for all patient and abuse specific data and health outcome variables, except when testing the dichotomous variable ‘perpetrator type (yes/no)’ and ‘suicide attempt (yes/no)’ where Pearson’s Chi2-test was used instead. STATA, version 16.1 (College Station, TX) was used.

Ethical considerations

The study started as a quality assurance project. However, as findings could be of interest for further research and discussion in a scientific context, ethical approval for the medical journal review was obtained from the regional ethical review board in Stockholm 09/01/19 (2019-00481).

Results

The results are presented in . The vast majority (90.9%) of the patients were women and childhood sexual abuse (CSA) was common among the included patients: 87.0% of the patients were <18 years old at the time of the first sexual abuse and 52.0% were ≤5 years old (). In total, 80.8% had been exposed repeatedly, i.e. more than once (), and 83.9% of the included patients had been subjected to penetrative abuse (). The mean time for the duration of the abuse period was 6.0 (SD 5.1) years, but 25.0% of the patients had been exposed for 10 years or more ().

Table 3. Participants health variables.

Table 4. Perpetrator details (number of patients answering the question n = 85).

Comorbidities were common, and the mean number of diagnoses given earlier or at admission to the specialist clinic was 6.3 (SD 2.6) (). The most common diagnoses among the included patients, made at admission to the specialist clinic or earlier, were; anxiety (89.8%); depression (88.1%); PTSD (85.2%); chronic pain (59.1%) and exhaustion disorder (52.3%) (). Suicide attempts were common and 38.4% of the patients had made at least one attempt and 25.6% had tried to commit suicide more than once. The mean ACE score was 3.5 (2.2). Among patients who completed self-ratings at admission, 92.7% scored above cut-off for PTSD (IES-R ≥ 34 points, mean 59.6 (SD 16.1)) and 85.5% scored above cut-off for depression (MADRS-S ≥ 13 mean 24.1 (SD 9.4)) (). The majority of the patients, 56.5%, had been abused by perpetrators in the family, and most commonly, 28.2%, by their biological father (). The strongest correlations between high number of diagnoses when contacting the clinic and other patient data, were number of ACEs (Spearman’s r = 0.4, n = 66, p=.001). The strongest correlation between suicide attempts and other patient data was number of ACE (Spearman’s 0.4, n = 79 p=.002), number of perpetrators (Spearman’s r = 0.4, n = 83, p=.0008) and father or other man to whom the patient had been dependent (Person’s Chi2 p=.0026 and p<.0001, respectively). No correlation was found between type of abuse and perpetrator.

Help-seeking patterns and disclosure

Among the included patients, 82.1% had sought healthcare within the public or private healthcare system before seeking healthcare at the specialist clinic (). The data with the strongest correlation with earlier healthcare seeking were number of ACE scores (Spearman’s r = 0.2, n = 78, p=.042) and number of diagnoses (Spearman’s r = 0.2, n = 84, p=.049). The mean time from the first sexual abuse to the first disclosure was 15.7 years (SD 15.3), however, 30.0% of patients had at least 20 years delay to disclosure (). The abuse data with the strongest correlations with late disclosure were number of years with sexual abuse (Spearman’s r = 0.5, n = 54, p=.001), followed by father being the abuser (Spearman’s r = 0.4, n = 79, p=.003) and age at onset (Spearman’s r=–0.3, n = 72, p=.0035). The most common individual to disclose to was biological mother (25.3%) followed by healthcare professional (22.8%) and friend (19.0%) (). Most likely to feel helped when disclosing, were those who disclosed to a sibling (66.7%) healthcare professionals (61.1%). However, even among those disclosing to healthcare professionals, 38.9% had not felt helped ().

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to describe patients with experiences of sexual abuse seeking help at a specialist clinic, with focus on patient and abuse related characteristics, disclosure, mental health and healthcare access.

First, patients seeking healthcare at the specialist clinic were mainly women, who had delayed disclosure for many years; a majority of the patients were five years or younger at onset, and mean time of disclosure delay was 16 years. That a majority of the included patients were women is in line with global accumulated knowledge of sexual abuse and gender based violence [Citation16]. The fact that the patients with CSA had delayed discloser for several years, and in many cases not until adulthood, is consistent with published data on narrative of disclosure of sexual abuse for both male and female [Citation11,Citation14,Citation25–32]. Delayed healthcare seeking and disclosure to healthcare professionals because of fear of not being believed if telling about their sexual abuse experience, or fear of simply not getting helped by possible healthcare interventions, has also been described in earlier studies [Citation30].

Second, the patients had severe health problems and had received multiple psychiatric diagnoses before admission to the specialist clinic. The high burden of disease, as indicated by the number of diagnoses, prevalence of suicide attempts and high scores on both IES-R and MADRS-S are in line with earlier studies analyzing associations between exposure to sexual abuse, a high burden of ACEs and poly victimization and health outcome later in life [Citation1–4,Citation19,Citation20,Citation33–42], as well as with high healthcare costs [Citation34].

Third, 82% of the patients in the study had disclosed and tried to access appropriate healthcare because of symptoms related to the sexual abuse before admission to the specialist clinic, but had not felt the help provided was enough. Furthermore, there was no correlation between prior healthcare access, and scores on IES-R and MADRS-S at admission to the specialist clinic. This indicates that the help provided earlier, was not sufficient for these patients.

A suggested model of gatekeeping mechanisms

Further understanding of possible barriers to appropriate non-emergency healthcare access for adult victims of sexual abuse, is a prerequisite for adequate policy changes for increased healthcare access to take place. We suggest a two-dimensional gatekeeping model, with three different categories, when conceptualizing these barriers. The two dimensions in the model include the perspective of healthcare systems, labeled as ‘External’ gatekeepers, and of healthcare seeking victims of sexual abuse, labeled as ‘Internal’ gatekeepers. The three categories of gatekeeping mechanisms in the suggested model are: Competence related Gatekeeping; Emotional Gatekeeping and Organizational Gatekeeping ().

Figure 1. A possible model for gatekeeping mechanisms. The model is applicable for both healthcare-systems and professionals (external dimension) and for healthcare-seeking victims of SA (internal dimension). The text in the boxes are examples of factors that may work as gatekeeping mechanisms to healthcare access for victims of SA.

Competence related gatekeeping: Earlier studies have found that low awareness or insufficient knowledge among healthcare providers of the health consequences of sexual abuse, increases the risk to dismiss or ignore disclosure of sexual abuse [Citation43,Citation44]. Insufficient understanding of psychological symptoms after sexual abuse as adaptive rather than pathological increases the risk to overlook exposure to sexual abuse as secondary to a psychiatric disorder, at expense of the former [Citation43]. The ability to convey compassion and empowerment were also identified as important competences needed among healthcare professionals in order to make victims of sexual abuse perceive the healthcare provided appropriate, in a meta-analysis from 2019 [Citation12]. These examples are labeled as external competence related gatekeeping mechanisms, and may partly explain the results from the present study, were a majority of the patients seeking help at the specialist clinic, had not felt the healthcare provided earlier was not sufficient. The internal dimension of the competence related gatekeeping includes the assumption that if the patient has insufficient understanding of her or his own symptoms and their possible association with the sexual abuse experiences, the likelihood to seek healthcare and to disclose to healthcare professionals ought to decrease. This hypothesis is the base of the internal dimension of the competence related gatekeeping mechanism, and it is also in line with the Barrier from Within described by Collin-Vezina et al. [Citation13]. Level of education as well as language knowledge might also be an internal competence related gatekeeping mechanism, lowering the access to appropriate healthcare, as demonstrated in this study. Organizational related gatekeeping: Sexual abuse is not a disease nor a diagnosis, and despite well documented associations between exposure and health consequences, it is not acknowledged as an etiological determinant for specific symptoms or diseases. In addition, patients exposed to sexual abuse may suffer from different symptoms and diagnosis often treated in different departments or clinics [Citation1–3]. Healthcare systems and interventions however are often organized in relation to specific symptoms or to diseases with acknowledged etiological determinants, like infectious, rheumatic, orthopedic or oncological clinics. Healthcare organization and at first sight non-cohesive symptoms and healthcare needs of victims of sexual abuse, might make it difficult for staff to know where to refer and what to offer the patient. Inexplicit and undefined roles and responsibility for these patients within each clinic may further decrease healthcare access [Citation43]. Earlier studies also suggest that patient autonomy with a wider control of the health care process than normally offered, is needed when treating victims of sexual abuse, and should be seen as an important factor contributing to the process of healing [Citation12,Citation45]. All these factors may be seen as an external dimension of the organizational gatekeeping mechanisms, and may partly explain the results from the present study, were a majority of the patients seeking help at the specialist clinic, had not felt the healthcare provided earlier was sufficient. The internal dimensions of the organizational gatekeeping mechanism are instead related to ‘negative symptoms’ such as partial or total dissociative amnesia, alexithymia or decreased ability to verbally express symptoms and tell about exposure to potentially harming experiences, because of repeated childhood traumas and PTSD [Citation46–50]. The results in this study, with high prevalence of ACEs, dissociation, amnesia and PTSD ( and ) among the patients, are in line with the proposed internal dimension of the organizational gatekeeping mechanism. Emotional related gatekeeping: For the external dimension, we intend health care professionals own emotional preparedness to listen to disclosure of sexual abuse, and to accept and confirm the presence of sexual abuse as a plausible origin of the symptom presentation of the patient. Even though closely related to the Competence related gatekeeping mechanism, and depending on both experience and access to education during basic and further professional healthcare education [Citation43], emotional preparedness is also depending on personal experiences and interests, and what we describe as the external dimension of the Emotional gatekeeping mechanisms can exist despite adequate formal competence among the healthcare professionals [Citation13]. The internal dimension of the emotional related gatekeeping mechanism includes feelings of guilt, shame, victim self-blaming and disgust within the patients, feelings of fear in regard to a dysfunctional family system as described by Collin-Vezina et al., as well as the patient’s preparedness to accept the own history of abuse as inhibitors of disclosure [Citation11,Citation13]. Finally, we also include possible feelings of fears within the patient, of not being understood or believed if disclosing their history of abuse to healthcare professionals, or of being offered healthcare that will increase rather than diminish the discomfort experienced [Citation12] to the internal emotional gatekeeping mechanism. For a summary of the three different categories in the proposed gatekeeping model, see .

The results of this present study indicate specialist clinics are indeed important, but not enough: the patients finding their way to the clinic studied are not representative for the general population, but were for instance higher educated and more linguistic homogenous than the population in general [Citation51]. This indicates coequal access to appropriate healthcare for adult victims of sexual abuse requires a cohesive healthcare chain, including both primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare, easily accessible patient information in different languages and clear structures for both referral and direct access to specialist clinics. To diminish the internal gatekeeping mechanisms, higher awareness and basic knowledge about sexual abuse, its common health consequences together with more information about where to seek help could, is probably needed among the population in general. Including this knowledge in sex education programs in schools could be one way of achieving this.

Implications for research and practice

Specialist clinics organized to the needs of sexually abused patients, with staff who has a specialist interest, education and emotional preparedness to recognize, assess, and treat sexually abused patients, is probably a key factor to diminish external gate-keepers, and to some extent, some of the internal gatekeeping mechanisms.

An incidental finding while using the semi-structured interview during the first visit at the specialist clinics, was the clinical experience of how defined categories and words for sexual abuse and its associated data, facilitated the assessment process for both doctor and patient, indicating that better categorization of sexual abuse related data could be useful for both staff and patients. The high prevalence of CSA among the patients at the clinic probably reflects that delay of disclosure tend to increase the prevalence of adult survivors of CSA with healthcare needs, compared to those exposed ‘only’ to adult sexual abuse. The needs among this group should be considered when planning healthcare organization. Finally, the proposed gatekeeping model needs to be studied more in depth by qualitative interviews and a broadened intake interview

Strengths and limitation

A strength of this quality assurance data is that data relates to consecutive cases that were collected in a similar way, and that all data contain register entries that provide greater understanding of the collected patient data. The small number of patients is however a limitation. The fact that the questions in the semi-structured intake interview were not originally constructed for research is another limitation, resulting in unknown reasons for why patients did not answer specific questions, and lack of data about ethnicity and socio-economic situation. Furthermore, all data were anamnestic, i.e. no objective or external validity check of collected data was made. Since the participants often described experiences that happened many years ago, memory bias could not be excluded in some cases. Despite these important limitations, the material is unique and creates opportunities for hypothesis generation and theory construction to be further tested.

Conclusion

Delayed healthcare access for victims of sexual abuse is a gender-based equality problem.

A gatekeeping model with three external and internal categories is proposed for further understanding and analysis of barriers to appropriate healthcare access for adult victims of sexual abuse.

Author contributions

GR researched data, drafted the manuscript and researched the literature ACC, CGS and GR designed the study; PW, LW; BP and CW contributed to the planning and editing of the manuscript.

Patientdata_eng.docx

Download MS Word (42.4 KB)Disclosure statement

Gita Rajan is the founder and president of the non-profit organization World of No Sexual Abuse, WONSA.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gita Rajan

Gita Rajan, PhD candidate, is a physician, specialized in family medicine. Dr Rajan is also the founder of the NGO World of No Sexual Abuse (WONSA). The vision of WONSA is a world of no sexual abuse and the mission is to increase the access to efficient health care for victims of sexual abuse.

Lars Wahlström

Lars Wahlström, PhD, is an expert in consultation liaison psychiatry at Stockholm Health Care Services and clinician at the CL Unit, Psykiatri SV at Karolinska University Hospital Huddinge and doctor of psychiatry. Formerly at Crisis and Disaster Psychology Unit at the Centre for Family Medicine.

Björn Philips

Björn Philips, associate professor of psychology at the Stockholm University, is a clinical psychologist who's main area of research and teaching is psychodynamic therapy, especially contemporary variants such as mentalization-based therapy, affect-focused therapy, and relational psychotherapy, and he is experienced on treatment studies.

Per Wändell

Per Wändell, appointed professor of general medicine at Karolinska Institutet in 2010 and director of studies for the Research School in General Practice at KI. Wändell's research aims to identify the best way for the healthcare system to reach patients in order to implement preventive measures.

Caroline Wachtler

Caroline Wachtler, PhD, is a physician, doctor in medicine, specialized in family medicine. Dr Wachtler’s clinical work as a resident in primary care (Stuvsta Primary care Center AB since 2009) informs her interest in mental health as she is daily made aware of the gap between research and practice. Caroline boasts a rare combination of skills in both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Carl-Göran Svedin

Carl Göran Svedin, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry since 2002. Prof. Svedin's research has covered areas such as child physical and sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, children exploited in child pornography, prostitution. He has been responsible for three previous Swedish epidemiological studies on young people's sexuality and sexual abuse (2004, -09, -14) and now carrying out the fourth.

Axel C. Carlsson

Axel C. Carlsson, associate professor at Karolinska Institutet with a demonstrated history of working in the higher education. Skilled in biomarkers, epidemiology, molecular biology. Dr Carlsson is principal for the research school in family medicine and primary care. He is also working as investigator at the Swedish Public Health Agency.

References

- Rajan G, Ljunggren G, Wandell P, et al. Diagnoses of sexual abuse and their common registered comorbidities in the total population of Stockholm. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(6):592–598.

- Rajan G, Ljunggren G, Wandell P, et al. Health care consumption among adolescent girls prior to diagnoses of sexual abuse, a case-control study in the Stockholm Region. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(10):1363–1369.

- Rajan G, Syding S, Ljunggren G, et al. Health care consumption and psychiatric diagnoses among adolescent girls 1 and 2 years after a first-time registered child sexual abuse experience: a cohort study in the Stockholm Region. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01670-w

- Rajan G, Wachtler C, Lee S, Wändell P, Philips B, Wahlström L, Svedin CG, Carlsson AC. A one-session treatment of PTSD after single sexual assault trauma. A pilot study of the WONSA MLI project: A randomized controlled trial. J Interpers Violence. 2020:886260520965973. PMID: 33084475. doi: 10.1177/0886260520965973

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Re-victimization patterns in a national longitudinal sample of children and youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(5):479–502.

- Lau M, Kristensen E. Sexual revictimization in a clinical sample of women reporting childhood sexual abuse. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(1):4–10.

- Moller A, Sondergaard HP, Helstrom L. Tonic immobility during sexual assault – a common reaction predicting post-traumatic stress disorder and severe depression. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(8):932–938.

- Papalia NL, Luebbers S, Ogloff JRP, et al. Further victimization of child sexual abuse victims: a latent class typology of re-victimization trajectories. Child Abuse Negl. 2017;66:112–129.

- Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, et al. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16(2):79–101.

- Jeong S, Cha C. Healing from childhood sexual abuse: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. J Child Sex Abus. 2019;28(4):383–399.

- Alaggia R, Collin-Vézina D, Lateef R. Facilitators and barriers to child sexual abuse (CSA) disclosures: a research update (2000–2016). Trauma Violence Abuse. 2019;20(2):260–283.

- Caswell RJ, Ross JD, Lorimer K. Measuring experience and outcomes in patients reporting sexual violence who attend a healthcare setting: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect. 2019;95(6):419–427.

- Collin-Vezina D, De La Sablonniere-Griffin M, Palmer AM, et al. A preliminary mapping of individual, relational, and social factors that impede disclosure of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;43:123–134.

- Smith DW, Letourneau EJ, Saunders BE, et al. Delay in disclosure of childhood rape: results from a national survey. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(2):273–287.

- WHO. Guidelines for medico-legal care for victims of sexual violence. World Health Organization; 2003.

- WHO. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization; 2013.

- Europe, C. o. (Istanbul, 11/05/2011). Council of Europe convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Vol. Treaty No. 210); 2011.

- SKR. Vården vid sexuellt våld, nuläge och vägar framåt; 2020.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258.

- Felitti VD, Robert FA. The adverse childhood experiences study; 2020.

- Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale – Revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489–1496.

- Murphy D, Ross J, Ashwick R, et al. Exploring optimum cut-off scores to screen for probable posttraumatic stress disorder within a sample of UK treatment-seeking veterans. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1398001.

- Bondolfi G, Jermann F, Rouget BW, et al. Self- and clinician-rated Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale: evaluation in clinical practice. J Affect Disord. 2010;121(3):268–272.

- Nejati S, Ariai N, Bjorkelund C, et al. Correspondence between the neuropsychiatric interview M.I.N.I. and the BDI-II and MADRS-S self-rating instruments as diagnostic tools in primary care patients with depression. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:177–183.

- Bonanno GA, Noll JG, Putnam FW, et al. Predicting the willingness to disclose childhood sexual abuse from measures of repressive coping and dissociative tendencies. Child Maltreat. 2003;8(4):302–318.

- Hebert M, Tourigny M, Cyr M, et al. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and timing of disclosure in a representative sample of adults from Quebec. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(9):631–636.

- Jonzon E, Lindblad F. Disclosure, reactions, and social support: findings from a sample of adult victims of child sexual abuse. Child Maltreat. 2004;9(2):190–200.

- McTavish JR, Sverdlichenko I, MacMillan HL, et al. Child sexual abuse, disclosure and PTSD: a systematic and critical review. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;92:196–208.

- Morrison SE, Bruce C, Wilson S. Children's disclosure of sexual abuse: a systematic review of qualitative research exploring barriers and facilitators. J Child Sex Abus. 2018;27(2):176–194.

- Patterson D, Greeson M, Campbell R. Understanding rape survivors' decisions not to seek help from formal social systems. Health Soc Work. 2009;34(2):127–136.

- Romano E, Moorman J, Ressel M, et al. Men with childhood sexual abuse histories: disclosure experiences and links with mental health. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;89:212–224.

- Somer E, Szwarcberg S. Variables in delayed disclosure of childhood sexual abuse. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(3):332–341.

- Barbosa LP, Quevedo L, da Silva Gdel G, et al. Childhood trauma and suicide risk in a sample of young individuals aged 14–35 years in southern Brazil. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(7):1191–1196.

- Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, et al. Health care utilization and costs associated with childhood abuse. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):294–299.

- Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(7):618–629.

- Elklit A, Christiansen DM. ASD and PTSD in rape victims. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25(8):1470–1488.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: II. Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35(10):1365–1374.

- Fergusson DM, McLeod GF, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and adult developmental outcomes: findings from a 30-year longitudinal study in New Zealand. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(9):664–674.

- Fjeldsted R, Teasdale TW, Bach B. Childhood trauma, stressful life events, and suicidality in Danish psychiatric outpatients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74(4):280–286.

- Hailes HP, Yu R, Danese A, et al. Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: an umbrella review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(10):830–839.

- Putnam KT, Harris WW, Putnam FW. Synergistic childhood adversities and complex adult psychopathology. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(4):435–442.

- Tiihonen Moller A, Backstrom T, Sondergaard HP, et al. Identifying risk factors for PTSD in women seeking medical help after rape. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111136.

- O'Dwyer C, Tarzia L, Fernbacher S, et al. Health professionals' experiences of providing care for women survivors of sexual violence in psychiatric inpatient units. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):839.

- Ranjbar V, Speer SA. Revictimization and recovery from sexual assault: implications for health professionals. Violence Vict. 2013;28(2):274–287.

- Snyder BL. Women's experience of being interviewed about abuse: a qualitative systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23(9–10):605–613.

- Chu JA, Frey LM, Ganzel BL, et al. Memories of childhood abuse: dissociation, amnesia, and corroboration. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5):749–755.

- Cottraux J, Lecaignard F, Yao SN, et al. Magneto-encephalographic (MEG) brain recordings during traumatic memory recall in women with post-traumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Encephale. 2015;41(3):202–208.

- Honkalampi K, Flink N, Lehto SM, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and alexithymia in patients with major depressive disorder. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74(1):45–50.

- Hull AM. Neuroimaging findings in post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:102–110.

- Williams LM. Recall of childhood trauma: a prospective study of women's memories of child sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(6):1167–1176.

- Education NAfH. Statistik analys; 2012.