Abstract

Purpose

This study evaluates the dimensionality and differential item functioning of SCL-9S, a short version of the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R), on patients in psychiatric care.

Material and methods

Based on the factor structure of the Swedish standardization and validation of the SCL-90-R, a nine-item index (SCL-9S) was developed consisting of the items most indicative for each of the nine subscales in SCL-90-R. Rasch analysis was used to evaluate the SCL-9S on a sample of 668 psychiatric outpatients and 167 inpatients across four Swedish regions.

Results

The evaluation revealed that the SCL-9S was unidimensional, the items represented different levels of severity across a general psychological distress dimension, and the scale showed equity (no differential items functioning) across gender and patient groups.

Conclusion

The SCL-9S is a fast, structurally valid, and reliable tool for screening general psychological distress among men and women in psychiatric in- and outpatient services, and in combination with other instruments, it will be useful in epidemiological studies.

Introduction

Symptoms impose psychological distress that has a negative effect on the health outcomes of patients [Citation1]. Thus, measurement of symptom presence is vital in health intervention assessments and in mental health epidemiological screening and modelling within the community as well as across clinical populations. In this regard, the Symptom-Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [Citation2] is a frequently used self-report multidimensional inventory for measuring a broad range of symptoms. However, the proposed multidimensional nine-factor structure of the SCL-90-R has been questioned [e.g. Citation3–5]. These studies as well as other studies contrasting different factor structures [e.g. Citation6] have expressed strong support for the idea that SCL-90-R is better conceptualized as a unidimensional measure of general psychological distress than a measure of nine independent symptom dimensions.

The SCL-90-R contain 90 items. The more items an instrument contain the higher its reliability and thus its potential validity [Citation7]. This circumstance rewards longer questionnaires. The unfavorable side is that long questionnaires take time to administrate and fill in, and for some patients it can be taxing to the extent that they are unable to complete the questionnaire with missing data or response errors as a result [Citation8]. Thus, the length of the questionnaire must be balanced with the desired precision of an instrument.

Considering the need for a briefer version of the SCL-90-R, particularly in contexts involving constraints over response time, several short versions have been developed [Citation9,Citation10,Citation11]. A variety of methods have been used to develop these short versions, including (i) selection of items with the highest primary and secondary factor loadings (e.g. SCL-6 [Citation12], SCL-27 [Citation13]), (ii) selection of the fewest number of items that can maintain the nine-factor structure (e.g. BSI-53 [Citation14], SCL-10R [Citation12]), (iii) selection of items relevant for the most common psychiatric disorders (e.g. BSI-18 [Citation15], SCL-10N [Citation16]), and (iv) selection of subscale items that showed the highest correlation with the mean of all items, i.e. the item total correlation, of the SCL-90-R (e.g. SCL-K-9 [Citation17], SCL-9-I [Citation18]). However, among the vast number of short versions, only the SCL-K-9 and the SCL-9-I have been explicitly developed to measure a unidimensional general distress factor. Based on confirmatory factor analysis, both SCL-K-9 and SCL-9-I show marginal support for unidimensionality [Citation10,Citation18].

Although classical test theory methods, such as factor analysis, have been the most frequently used methods to investigate the dimensionality of the SCL-90-R and its short versions, some studies have used item response theory methods, such as Mokken scaling [Citation19,Citation20] or Rasch analysis [Citation21]. These methods are favorable for developing and evaluating unidimensional scales since they overcome some of the shortcomings of factor analysis by being less sample-specific, less sensitive to the symptom base rate, and more capable of representing the test-takers and the difficulty of the items as independent parameters [Citation22].

Another factor to be considered is that the SCL-90-R short versions developed to measure a general distress factor were not developed on clinical population data. Instead, the SCL-K-9 was developed on a general population and the SCL-9-I, on infertile couples. Given that an instrument should be psychometrically evaluated on the intended population [Citation23], any short versions of SCL-90-R intended for use in a psychiatric patient population should be developed on this population. Correspondingly, a unidimensional short version of the SCL-90R developed for the Swedish psychiatric care situation is relevant since studies using the Swedish version of the SCL-90-R on patient populations agree with international studies suggesting a unidimensional structure of the SCL-90-R [Citation24,Citation25].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published SCL-90-R short versions providing a unidimensional measure of general psychological distress based on item response theory methods in patients under psychiatric care. Therefore, a short version, SCL-9S, was developed. To preserve the construct validity and clinical validity of SCL-90-R, the items most indicative of a symptom dimension was chosen, i.e. the items with the highest loading in each subscale in the validation of the SCL-90-R on patients from psychiatric in- and outpatient clinics across Sweden [Citation24]. By using Rasch analysis, different groups of respondents can be compared regardless of the raw score distributions, and by examining the properties of the SCL-9S for different groups (i.e. type of psychiatric care or gender), one can examine item equivalence in terms of differential item functioning (DIF) to determine whether an item is endorsed similarly across gender and type of psychiatric care groups. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the dimensionality and DIF of the SCL-9-S on patients under psychiatric care.

Methods

Participants and procedure

A total of 835 psychiatry patients from 26 clinics at four regions in central Sweden participated in the study. The patients completed a questionnaire containing the SCL-9S and questions regarding patient characteristics, which are shown in . The inpatients completed the questionnaire at the ward during discharge whereas the outpatients completed it during a visit at the clinic as a part of ongoing treatment. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

SCL-9S

The SCL-9S () includes items from all nine of the original SCL-90-R subscales to preserve the content validity and representativity across the broad spectrum of psychiatric symptomatology captured by the SCL-90-R. The selected nine items had the highest loading in each subscale of the SCL-90-R in the Swedish validation of the SCL-90-R [Citation24]. Each item was scored, as on the SCL-90-R, on a five-point Likert type scale from 0 = none to 4 = extremely.

Table 2. Items and dimensions of the SCL-90-R and SCL-9S.

Background questions

In addition to the SCL-9S, and as shown in , the patients were asked of their age, gender, living status, education level, current occupation, diagnosis, and treatment. They were also asked to rate their perceived mental health on a five-point Likert type scale from 1 = very bad to 5 = very good.

Statistical analyses

Rank-ordered scores were analyzed using the Rasch rating scale model with Winsteps 3.81.0 [Citation26]. A detailed explanation of Rasch models is provided elsewhere [Citation27]. One-parameter Rasch analysis with DIF was applied to further explore the dimensionality and group equivalence of the SCL-9S. Cronbach’s alpha [Citation28] was used to assess the internal consistency of the scale. Coefficients higher than 0.7 [Citation29] and ceiling and floor effects < 10% [Citation30] were considered acceptable. Descriptive statistics were computed using the statistical software package SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Principal-component analysis of residuals was used to examine the dimensionality of the SCL-9S. Unidimensionality was considered to exist if at least 50% of the total variance was explained by the first component and any additional components had an eigenvalue lower than 2 or explained less than 5% of the remaining variance after removal of the first component [Citation26]. In addition, there should be more than 10 responses in each rating category, the average person measure should increase with the rating category, thresholds should be ordered, and category infit and outfit mean square values should be below 1.5. To evaluate whether the range of items was appropriate for the samples, a targeting value between −1.0 and 1.0 logits was considered acceptable. Differential item functioning was used to examine whether an item performed differently for men and women and differently for the two patient groups, and DIF was considered to be present if the difference between the two groups on an item measure was 0.5 logits or more and reached significance (p < 0.05) in a t-test [Citation31]. To further identify how the patients were grouped regarding symptomatology, K-means clustering with Ward’s method was conducted. To investigate convergent validity, variables that may explain the variations in psychological distress measured by the SCL-9S were analyzed using stepwise multiple regression. In all analyses, a pvalue of 0.05 or smaller was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demography

Participant characteristics are listed in . The outpatient group contained more women while the inpatient group contained more men. The age range in both groups was similar, but the outpatients were approximately 10 years younger, and relatively more of them were living with a partner. Outpatients had a higher educational level, and although both groups showed no differences in occupation, a larger proportion of inpatients had retirement pension. Relatively more outpatients knew their diagnoses. The most common diagnosis among outpatients in comparison with inpatients was attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorder, and personality disorder. More inpatients had been treated with medication and electroconvulsive therapy whereas more outpatients had undergone counselling and psychotherapy. Finally, inpatients perceived their mental health as somewhat better than did the outpatients.

Rasch analysis

Rating categories

The principal component analysis of the residuals showed that the variance explained by the measures was 50%, and the eigenvalue and unexplained variance of the first contrast were 1.7 and 9.7%, respectively, suggesting that the SCL-9S is unidimensional.

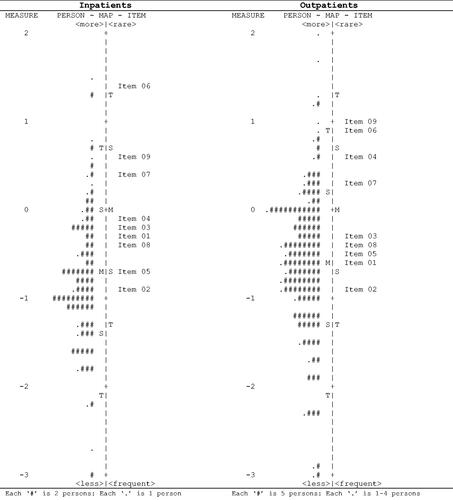

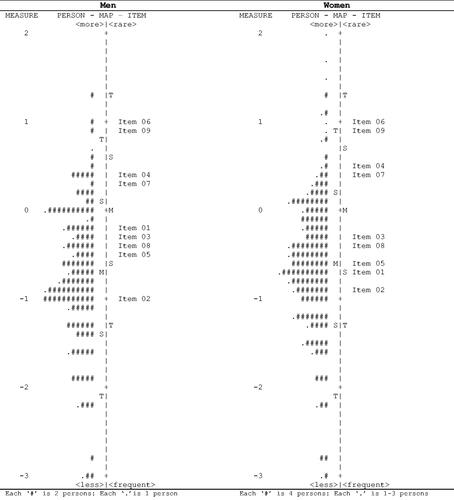

Person measures

Both patient groups fulfilled the rating scale criteria (), i.e. there were more than 10 responses in each rating category, the average person measure increased with the rating category, thresholds were ordered, and category infit and outfit mean square values were below 1.5. In terms of mean item difficulty, item 2 was the easiest to endorse in both patient groups, whereas the most difficult item to endorse in the inpatient group was item 6 and that in the outpatient group was item 9 (). The mean SCL-9S person measures for the gender and patient groups are shown in . Analysis of variance showed no significant differences related to gender and patient group (p = 0.25 and 0.52) or gender by group interaction (p = 0.95) of the SCL-9S mean score.

Table 3. Summary statistics for the five SCL-9S rating scale categories for inpatients (IP) and outpatients (OP).

Table 4. Fit statistics.

Table 5. Item mean raw score (M) and standard deviations (SD) for men and women in the inpatient (IP) and outpatient (OP) groups.a

Floor and ceiling effects

Eight individuals (1.2%) in the outpatient group and two (1.3%) in the inpatient group scored a zero (not at all) on all nine items whereas non scored a four (extremely) on all nine items, demonstrating the absence of floor and ceiling effects.

Targeting

The range of SCL-9S items in the in- and outpatient samples showed acceptable targeting of −0.77 and −0.62 logits, and those for women and men also showed acceptable targeting of −0.60 and −0.74 logits, demonstrating that the SCL-9S scale was relevant for the chosen population.

Differential item functioning

Person-item maps for patient groups and gender are shown in . Although men and women showed no DIF, two items showed minor DIF between the inpatient and outpatient groups: item 4 (−0.63 logits) and item 6 (0.56 logits). Given the identical levels of perceived psychological distress, item 4 ‘Thoughts of ending your life’ was thus more likely to be endorsed by those in the inpatient group whereas item 6 ‘Shouting or throwing things’ was more likely to be endorsed by those in the outpatient group.

Scale reliability and separation

The reliability for the full sample was 0.75, varying between 0.72–0.79 for the patient group and gender subsamples. Person separation of the full sample was 1.75 and item separation was 17.19, translating into three and 23 distinct strata, respectively. Thus, the high item separation demonstrates the construct validity (i.e. item difficulty hierarchy) of the SCL-9S and the moderate person separation indicates that the SCL-9S may be sensitive enough to distinguish between high-, medium-, and low-severity groups.

Convergent validity

The SCL-9S score showed a moderate correlation with patient’s perceived mental health (r = −0.55, p < 0.001), indicating that greater psychological distress is related to worse mental health and supporting the convergent validity of the SCL-9S. The regression analysis used to investigate variables that may explain the variation in the psychological distress measured by the SCL-9S showed that, in addition to worse mental health (β = −0.43, p < 0.001), diagnoses of anxiety (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), personality disturbances (β = 0.08, p = 0.015), or autism spectrum disorder (β = 0.07, p = 0.034), as well as perceived worse physical health (β = −0.16, p < 0.001), and psychotherapy (β = 0.08, p = 0.009) were associated with greater psychological distress whereas older age (β = −0.07, p = 0.028) and electroconvulsive therapy (β = −0.07, p = 0.020) were associated with lower psychological distress. The model had an R2 of 0.38. Neither gender nor patient group contributed significantly to the model.

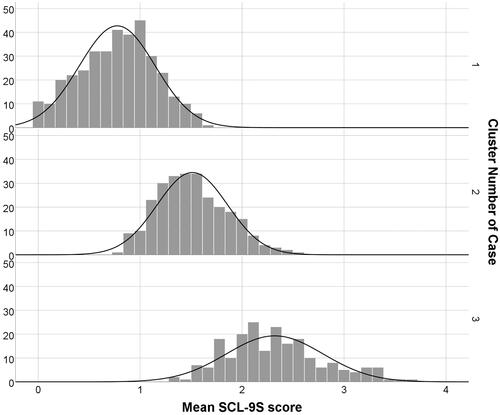

Cluster analysis

K-means clustering suggested the presence of three similar sized clusters, as indicated by the Rasch separation statistics (). As seen in , cluster 1 had the lowest SCL-9S mean scores, followed by cluster 2 and cluster 3, which had the highest mean scores on all items except item 1 ‘Soreness of your muscles’, which was instead endorsed the most by patients in cluster 2. Item 2 ‘Feeling blocked in getting things done’ did not discriminate between clusters 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Person item maps for men and women. Note. M: mean of person or item distribution; S: one standard deviation from the person or item mean; T: two standard deviations from the person or item mean.

Table 6. Mean scores per item of the SCL9S across patient clusters.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the dimensionality and DIF of the SCL-9-S in patients under psychiatric care. To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize Rasch analysis to evaluate a short form of the SCL-90-R in a clinical population. The results demonstrated that the SCL-9S was unidimensional and thus corroborated previous research suggesting that the full SCL-90-R is best used as a global index of symptom severity. Moreover, we found that the SCL-9S rating categories advanced monotonically from not at all to extremely and that the patients could effective discriminate between categories.

The SCL-9S also showed equality across gender and patient groups, except for minor DIFs observed between the inpatient and outpatient groups for two of the items. Item 4 ‘Thoughts of ending your life’ was more likely to be endorsed by those in the inpatient group whereas item 6 ‘Shouting or throwing things’ was more likely to be endorsed by those in the outpatient group. The possible source of this DIF is difficult to explain, since the two patient groups did not differ in average psychological distress. Although the inpatient group contained more men and the outpatient group contained more women, and gender-related differences have been reported in both throwing objects [Citation32] and suicidal thoughts [Citation33] , no gender-related DIFs were identified. Thus, it is less likely that gender bias has influenced the item DIF. Considering the observed minor DIF, the SCL-9S may by all practical means indicate similar function across gender and patient groups, and comparison across these groups will be meaningful.

Item separation indicated the existence of 17 discrete item severity strata, clarifying the progressive endorsement difficulty of items along the measured distress dimension and confirming the hierarchy of item endorsement difficulty (i.e. construct validity) of the SCL-9S. Consistent with previous research [Citation21,Citation34]), Rasch analysis categorized anxiety, somatization, and social insecurity as ‘easier’ items to endorse at a given location on the latent variable, whereas hostility and psychoticism items were more ‘difficult’ to endorse.

The person separation statistics revealed the possibility of discriminating among three person strata, which was supported by cluster analysis. The three clusters identified were characterized by a low psychological distress cluster (1) and a high psychological distress cluster (3) with an intermediate psychological distress cluster (2), which was, however, distinctively differentiated from the other two clusters by a high level of somatization by item 1 ‘Soreness of your muscles’. Only item 2 ‘Feeling blocked in getting things done’ did not differentiate clusters 2 from 3.

Convergent validity of the SCL-9S was supported by the association between greater perceived psychological distress and worse perceived worse mental health. The multiple regression analysis showed that in addition to mental health, other factors such as perceived physical health, age, diagnoses, and treatments were independently associated with perceived psychological distress. The regression model, however, explained about one-third of the variance of psychological distress. Thus, there are potentially additional factors not identified in the present study that may explain the variance in psychological distress.

Limitations

Although the SCL-9S showed adequate psychometric properties as a short version of the SCL-90-R, some limitations should be noted. First, since the patients only completed the items of the SCL-9S, we were not able to assess whether the SCL-9S is more suited to the Swedish psychiatry context than any of the other available short versions of the SCL-90-R. Second, the observed DIF values were practically negligible, but from a theoretical perspective, more demographic information might have shed light on the source of the DIF observed. Finally, the study did not include a community sample; thus, we were not able to estimate clinically relevant cut-off values.

Conclusion

The SCL-9S is a fast, structurally valid, and reliable tool for screening psychological distress among patients in psychiatric care, and in combination with other instruments, it will be useful in epidemiological studies.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the regional research ethics committee at Uppsala, Sweden (reference number: dnr 2018/186).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lars-Olov Lundqvist

Lars-Olov Lundqvist, associate professor of Psychology, adjunct professor of Disability Research, and research leader at the University Healthcare Research Center at Örebro University. Research areas of interests are disability science, affective neuroscience, and psychometrics.

Agneta Schröder

Agneta Schröder, RNT, professor of Nursing Science at Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Norway, and associate professor of Medical Science and research leader at the University Healthcare Research Center at Örebro University. Research areas are focused on quality of psychiatric care, instrument development, and psychometrics.

References

- Barry V, Stout ME, Lynch ME, et al. The effect of psychological distress on health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Health Psychol. 2020;25(2):227–239.

- Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R, administration, scoring and procedures manual-II for the R(evised) version and other instruments of the Psychopathology Rating Scale Series. Townson: Clinical Psychometric Research;1992.

- Bonynge ER. Unidimensionality of SCL‐90‐R scales in adult and adolescent crisis samples. J Clin Psychol. 1993;49(2):212–215.

- Smits IA, Timmerman ME, Barelds DP, et al. The Dutch symptom checklist-90-revised. Is the use of the Subscales Justified? Eur J Psychol Assess. 2015;31(4):263–271.

- Urbán R, Kun B, Farkas J, et al. Bifactor structural model of symptom checklists: SCL-90-R and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) in a non-clinical community sample. Psychiatry Res. 2014;216(1):146–154.

- Arrindell WA, Urbán R, Carrozzino D, et al. SCL-90-R emotional distress ratings in substance use and impulse control disorders: one-factor, oblique first-order, higher-order, and bi-factor models compared. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:173–185.

- Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, et al. Multivariate data analysis. 4th ed. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ:Prentice Hall; 1995.

- Waller G, Meyer C, Ohanian V. Psychometric properties of the long and short versions of the Young Schema Questionnaire: Core beliefs among bulimic and comparison women. Cogn Ther Res. 2001;25(2):137–147.

- Müller JM, Postert C, Beyer T, et al. Comparison of eleven short versions of the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R) for use in the assessment of general psychopathology. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(2):246–254.

- Prinz U, Nutzinger DO, Schulz H, et al. Comparative psychometric analyses of the SCL-90-R and its short versions in patients with affective disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):104.

- Sereda Y, Dembitskyi S. Validity assessment of the symptom checklist SCL-90-R and shortened versions for the general population in Ukraine. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–11.

- Rosen CS, Drescher KD, Moos RH, et al. Six- and ten-item indexes of psychological distress based on the Symptom Checklist-90. Assessment. 2000;7(2):103–111.

- Hardt J, Gerbershagen HU. Cross-validation of the SCL- 27: a short psychometric screening instrument for chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2001;5(2):187–197.

- Derogatis LR, Spencer P. Brief symptom inventory: BSI. Upper Saddle River: Pearson; 19 93.

- Derogatis LR. The Brief-Symptom-Inventory-18 (BSI-18): administration, scoring and procedures manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems: MN; 2000.

- Nguyen TD, Attkisson CC, Stegner BL. Assessment of patient satisfaction: development and refinement of a service evaluation questionnaire. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6(3-4):299–314.

- Klaghofer R, Brähler E. Konstruktion und Teststatistische Prüfung einer Kurzform der SCL-90-R. Psychiatrie Und Psychotherapie. 2001;49:115–124.

- Martínez-Pampliega A, Herrero-Fernández D, Martín S, et al. Psychometrics of the SCL-90-R and development and testing of brief versions SCL-45 and SCL-9 in Infertile Couples. Nurs Res. 2019;68(4):E1–E10.

- Paap MC, Meijer RR, Cohen-Kettenis PT, et al. Why the factorial structure of the SCL-90-R is unstable: comparing patient groups with different levels of psychological distress using Mokken Scale Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):819–826.

- Schmitz N, Hartkamp N, Kiuse J, et al. The symptom check-list-90-R (SCL-90-R): a German validation study. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(2):185–193.

- Elliott R, Fox CM, Beltyukova SA, et al. Deconstructing therapy outcome measurement with Rasch analysis of a measure of general clinical distress: the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised. Psychol Assess. 2006;18(4):359–372.

- DeVellis RF. Scale development: theory and applications. Vol. 26. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications; 2016.

- International Test Commission. ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests (second edition). Int J Testing. 2018;18(2):101–134.

- Fridell M, Cesarec Z, Johansson M, et al. SCL-90. Svensk Normering. Standardisering och Validering av Symtomskalan [SCL 90. Swedish Normalisation, Standardisation and Validation of the Symptom Scale.]. Stockholm: Statens Institutionsstyrelse SiS; 2002.

- Rytilä-Manninen M, Fröjd S, Haravuori H, et al. Psychometric properties of the Symptom Checklist-90 in adolescent psychiatric in-patients and age-and gender-matched community youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2016;10(1):23.

- Linacre JM. A User’s Guide to WINSTEPS. Chicago, IL: Winsteps.com; 2014.

- Engelhard Jr G. Invariant measurement: using Rasch models in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. New York: Routledge; 2013.

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334.

- Nunnally J, Bernstein I. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;1994.

- Bond TG, Fox CM. Applying the Rasch model: fundamental measurement in the human sciences. 2nd ed. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 20 07.

- Karami H. An introduction to differential item functioning. Int J Educ Psychol Assess. 2012;11(2):59–76.

- Campbell A, Muncer S. Intent to harm or injure? Gender and the expression of anger. Aggress Behav. 2008;34(3):282–293.

- World Health Organization 2016. Suicide data. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/

- Kopta SM, Howard KI, Lowry JL, et al. Patterns of symptomatic recovery in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(5):1009–1016.