Abstract

Purpose

To perform a systematic review on the use of maintenance treatment to prevent relapse and recurrence in patients with psychotic unipolar or bipolar depression.

Methods

We conducted an electronic search in December 2019 (and an updated search in July 2021) of four databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane) to identify controlled studies comparing the relapse rates of patients receiving maintenance treatment for psychotic unipolar depression and psychotic bipolar depression. A meta-analysis was made that included three studies comparing antidepressant (AD) and antipsychotic (AP) combination therapy with AD monotherapy. We used the GRADE tool to assess the quality of evidence.

Results

We included five randomized controlled trials fulfilling the inclusion criteria, making three comparisons: (a) AD + AP versus AD monotherapy; (b) AD + AP versus AP monotherapy; (c) AD + electroconvulsive therapy versus AD monotherapy. The included studies only examined patients with psychotic unipolar depression. The largest included study reported a statistically significant advantage of AD + AP compared with AD monotherapy. We made a meta-analysis of the three studies comparing AD + AP combination therapy with AD monotherapy, which included 195 patients and 56 events. The meta-analysis did not show a statistically significant difference between these treatments.

Conclusions

Contrary to the finding of the largest study, we did not find a statistically significant difference between AD + AP combination therapy and AD monotherapy in the meta-analysis. There is insufficient evidence to support the superiority of any treatment modality as maintenance treatment for psychotic depression. Further studies are required.

Introduction

Psychotic unipolar depression has an estimated lifetime prevalence of between 0.35% and 1% [Citation1]. Patients with psychotic unipolar depression have more severe episodes than patients with non-psychotic depressive episodes [Citation1,Citation2]; thus effective treatment is of great importance.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective acute treatment for psychotic unipolar depression, with treatment responses of 70% and above [Citation3–5]. Antidepressants (AD) and antipsychotics (AP) are other established acute treatment options. There have been suggestions that combination therapy with AD + AP is more effective than either treatment as monotherapy [Citation6,Citation7]. The treatment guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association recommend ECT or combination therapy with AD + AP as first-line acute treatment. However, the American Psychiatric Association does not present any specific guidelines for the maintenance treatment of psychotic unipolar depression [Citation8].

In 2011, Farahani et al. made a systematic review examining the efficacy of AD and AP (but not other interventions) as maintenance treatments. They identified one randomized controlled trial that investigated maintenance treatment [Citation6]. Since then, further studies have been published on maintenance treatment for psychotic unipolar depression. However, we have not found any systematic reviews on maintenance treatment for psychotic bipolar depression. Thus, a systematic review examining the evidence of maintenance treatment for psychotic unipolar and bipolar depression is warranted. For the purposes of this review, maintenance treatment is defined as an intervention given after a patient has either remitted or responded to acute treatment.

Aims of the study

To perform a systematic review on the effectiveness of maintenance treatment to prevent relapse and recurrence in patients with psychotic unipolar depression or psychotic bipolar depression who have responded to acute treatment.

Methods

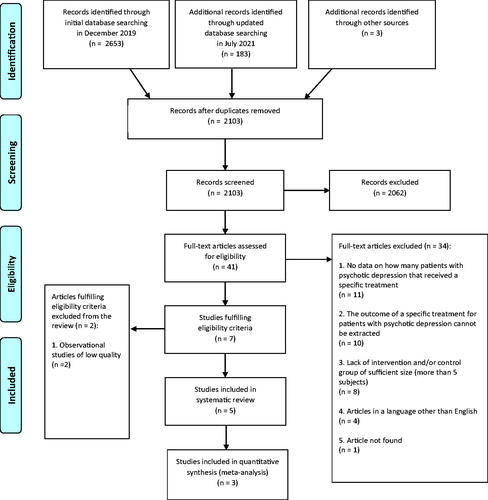

The PRISMA guidelines were followed for this systematic review [Citation9]. A PRISMA checklist is presented in Supplemental Appendix 1. We searched for controlled studies examining the outcome of maintenance treatment in patients diagnosed with either psychotic unipolar depression or psychotic bipolar depression. In , an overview of the search strategy and collection of data items is presented.

Table 1. Overview of search strategy and collection of data items.

Synthesis of results and risk of bias within and across studies

Quality assessment of the individual studies

To evaluate the quality of the individual studies, the Jadad scale was used, which consists of three items: randomization (0–2 points), double-blinding (0–2 points) and withdrawals and drop-outs (0–1 point). The maximum score is 5 points; 0–2 points indicate that the study is of low quality, and 3–5 points indicate high quality [Citation10].

Meta-analysis

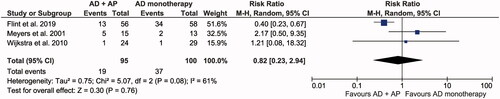

The software RevMan 5.4 (developed by the Cochrane collaboration) was used to conduct a meta-analysis, which consisted of three studies comparing AD + AP combination therapy with AD monotherapy. The outcome was whether a patient suffered a relapse or not. A random effects model was used due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 61%). Risk ratio was chosen as the effect measure to facilitate data interpretation. Mantel–Haenszel was chosen as statistical method.

GRADE assessment

We used the system of Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) to evaluate the summarized quality of evidence for the studies comparing the effects of AD + AP combination therapy with AD monotherapy. There are four levels to classify the quality of evidence: very low, low, moderate, and high. Observational studies without any special strengths or limitations are considered to provide low-quality evidence, whereas randomized controlled trials without significant limitations provide high-quality evidence. The GRADE score can be lowered by 1–2 levels for each of the following factors: limitations in the study design or execution (risk of bias), inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision, and publication bias. The GRADE score can be elevated by 1–2 levels if the effect size is large. The score is raised by one level if a dose-response gradient is shown, and also if all plausible confounding would reduce the demonstrated effect or increase the effect if no effect was observed (this specific criterion is only applicable for observational studies) [Citation11]. For comparisons of interventions where only one article is published, a total GRADE score was not given. However, we evaluated the applicable abovementioned factors and discussed them narratively for these comparisons.

Results

Study selection

The initial search in December 2019 generated six studies that met our inclusion criteria. In July 2021, we conducted a second search, with the same search string and databases as in the initial search, identifying one additional study. Of the seven identified studies, five were RCTs. The two other studies were not included in this review due to being observational studies of low quality [Citation12,Citation13]. A flow diagram of the study selection is presented in . A description of the main reasons for excluding articles after the full-text analysis is presented in Supplemental Appendix 3.

In all included studies, patients were classified as having psychotic unipolar depression according to DSM-IV or DSM-IV-TR criteria; thus, none of the articles examined patients with psychotic bipolar depression.

Of the included articles, three compared the combination of AD + AP with AD alone or alongside placebo [Citation14–16]; one study compared the combination of AD + AP with AP and placebo [Citation17]; and one study compared ECT and AD with AD alone [Citation18]. Below, we present the results of these comparisons.

Quality assessment of the individual studies

All included studies were deemed to be of high quality according to the Jadad scale (see ). All studies described using computer-generated randomization, except for the study by Meyers et al., where the randomization method was not mentioned. Double-blinding was mentioned in the studies by Flint et al., Meyers et al., and Bingham et al. and in all these studies it was implied that neither the study participant nor the person doing the assessment could identify the intervention. The study by Navarro et al. was single-blinded (and thus 0 points was given for blinding). The study by Wijkstra et al. was blinded in the acute phase of the treatment but was unblinded during the maintenance phase. Complete data of withdrawal was presented in the studies by Flint et al., Wijkstra et al., and Navarro et al.

Table 2. Quality assessment of individual studies.

AD + AP versus AD monotherapy

We found three randomized controlled studies comparing the efficacy of AD + AP combination therapy with AD monotherapy.

In the largest study by Flint et al. combination therapy with sertraline and olanzapine was superior to sertraline and placebo; of patients who finished the study, 13/56 patients in the combination group relapsed, whereas 34/58 patients in the sertraline monotherapy group relapsed [Citation14]. The difference is statistically significant and gives a number needed to treat of 2.82 (95% CI: 1.87–5.77).

The other two studies were smaller, had few relapses, and did not show any significant difference between combination therapy and monotherapy. In the study by Wijkstra et al. 1/24 patients who finished the study relapsed when receiving venlafaxine and quetiapine combination therapy, 1/17 relapsed when receiving imipramine monotherapy, and 0/12 relapsed when receiving venlafaxine monotherapy [Citation16].

In the study by Meyers et al. 5/15 patients who received nortriptyline and perphenazine combination therapy relapsed compared with 2/13 patients who received nortriptyline monotherapy [Citation15].

The patient characteristics, criteria for inclusion after acute treatment, and definition of relapse were similar between the studies and are presented in .

Table 3. Patient characteristics, post-acute treatment status, and relapse definition of studies comparing AD + AP with AD monotherapy.

Meta-analytic comparison

Combination therapy was favored over monotherapy, but the effect was not statistically significant (p = 0.76). For the study by Wijkstra et al. we combined the results of the venlafaxine monotherapy group and imipramine monotherapy group as an AD monotherapy group. The meta-analysis is presented in .

GRADE assessment

We assessed that the total quality of evidence to support the use of combination therapy over monotherapy was very low. The initial rating was reduced by three levels based on inconsistency (−1 level) and imprecision (−2 levels) of the results. The inconsistency was based on substantial heterogeneity between studies. Imprecision resulted from a low number of study participants and events. See for a summary of the GRADE scoring. In , we present some other observed differences and deficiencies between the studies that were not severe enough to downgrade the quality of evidence.

Table 4. GRADE scoring of studies comparing AD + AP with AD monotherapy.

Table 5. Other differences and deficiencies of studies comparing AD + AP with AD monotherapy.

AD + AP versus AP monotherapy

In a study by Meyers et al. patients with psychotic unipolar depression were randomized under double-blind conditions to receive either olanzapine and sertraline combination therapy or olanzapine and placebo as acute treatment [Citation19]. Bingham et al. conducted a continuation study in which patients who achieved remission continued to receive the same treatment, in what was called a ‘stabilization phase’, for another 12 weeks (still under double-blind conditions) [Citation17].

Bingham et al. defined relapse as 2 consecutive weeks fulfilling at least one of the following criteria: (a) Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) score ≥ 18; (b) meeting symptomatic criteria for major depressive disorder according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID); or (c) SCID-rated psychosis and a score of ≥3 on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) delusion or hallucination severity items.

Of patients receiving combination therapy, 6/46 patients relapsed compared with 2/25 receiving olanzapine monotherapy, but the difference was not statistically significant. Data on potential drop-outs were not reported.

There was a statistically significant difference (but not regarded as clinically meaningful) in the baseline HDRS score after the acute treatment; the mean score was 3.96 (SD 2.75) in the combination group and 5.32 (SD 2.67) in the monotherapy group. Besides this, the patient characteristics in the study by Bingham et al. were similar, with no reported statistically significant differences between the treatment groups. The mean age was 59.7 years (SD 17.3) in the combination group and 60.1 years (SD 15.4) in the monotherapy group. In the group receiving combination therapy, 71.7% were female, whereas 64.0% were female in the group receiving olanzapine monotherapy.

ECT + AD versus AD monotherapy

In a randomized study by Navarro et al. 38 elderly patients aged 60 and older with psychotic unipolar depression received acute treatment with ECT and nortriptyline [Citation18]. In patients who remitted, 16 received nortriptyline and ECT as a maintenance treatment. The ECT was administered weekly for the first month, and then every 2 weeks for another month, and then monthly until the end of the follow-up after 2 years. This group was compared with a group of 17 patients remitting from acute treatment who received nortriptyline monotherapy as maintenance treatment. The patients treated with nortriptyline monotherapy also received risperidone for 6 weeks after cessation of acute treatment; the dose of risperidone was gradually tapered-off for another 4 weeks. The study was conducted under single-blind conditions during the maintenance phase.

A survival analysis measuring the number of relapses and recurrences during the 2-year study period was conducted. Re-emergence of depressive symptoms according to DSM-IV and a HDRS score ≥ 16 within 6 months of the end of treatment was defined as a relapse, and after 6 months this re-emergence was defined as a recurrence. In the nortriptyline monotherapy group, 8/13 participants that completed the study either relapsed or experienced recurrence. In the ECT and nortriptyline group, only 1/12 patients relapsed.

In the monotherapy group, 23.5% of the patients (4/17) dropped out and in the combination group, 25% (4/16) dropped out.

The patient characteristics were similar between the treatment groups. The mean age prior to the acute treatment was 70.4 years (SD 3.2) in the combination group and 70.7 years (SD 3.4) in the monotherapy group. In the combination group, 62.5% of the participants were female compared with 64.7% in the monotherapy group.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of maintenance treatment to prevent relapse in psychotic unipolar and psychotic bipolar depression. After full-text analysis, five RCT studies were included on psychotic unipolar depression, whereas we did not identify any controlled studies on psychotic bipolar depression. Thus, the discussion below relates to psychotic unipolar depression.

In our meta-analysis we did not find a statistically significant difference between AD + AP combination therapy and AD monotherapy. However, this should be interpreted with caution. In the only study that provided high-quality evidence by Flint et al. there was a distinct superiority of combination treatment, with a number needed to treat of 2.82 (95% CI: 1.87–5.77). Several factors also raise the question of whether the included studies are too heterogeneous to be synthesized in a meta-analysis. Firstly, the studies by Wijkstra et al. and Meyers et al. were significantly smaller and had few events. When combined, these two studies had less participants than the study by Flint et al. and only yielded data on nine relapses.

An explanation for the low number of events in these studies may arise from the smaller sample size, and the shorter treatment duration and follow-up times used by Wijkstra et al. (15 weeks) and Meyers et al. (26 weeks) compared with Flint et al. (8 weeks of stabilization treatment and 36 weeks of maintenance treatment).

The optimal duration of maintenance treatment following remission is unclear. Rothschild et al. suggested that the majority of patients with psychotic unipolar depression do not need treatment with AP for more than 4 months [Citation20]. This notion is based on a small uncontrolled study in which 30 patients with psychotic unipolar depression who had achieved remission were treated with fluoxetine and perphenazine for 3 months (plus 1 month of acute treatment). After that, the dose of perphenazine was tapered-off; 22/30 patients remained well until the end of the study 11 months later. The remaining 8/30 patients showed signs of impending relapse within 2 months of the tapering. All patients regained remission when perphenazine treatment was reinstated. When a new attempt was made to taper-off perphenazine, 3/8 patients once more presented with symptoms of impending relapse. On the other hand, a study by Naz et al. indicated that a high proportion of relapses may occur after 1 year, whether patients are obtaining treatment or not [Citation21]. In their study, 60 patients who had achieved remission after an episode of psychotic unipolar depression were followed-up for 4 years, during which 26 patients relapsed. The median time for relapse was 50.0 weeks (interquartile range: 30.3–78.6 weeks). The authors concluded that treatment after achieving remission was not significantly associated with time-to-relapse. Since the optimal duration of maintenance treatment is not known, we suggest that future studies adhere to the protocol of Flint et al. with a follow-up time of at least 36 weeks.

Another factor that may influence the heterogeneity of the results is that each study used a different acute treatment. In the study by Meyers et al. all patients achieved remission with ECT. In the study by Wijkstra et al. the patients continued to receive the acute treatment that led to remission (i.e. the maintenance AD monotherapy group achieved remission with acute AD monotherapy), whereas in the study by Flint et al. all patients achieved remission with combination treatment, and then AP was removed from the AD monotherapy group in the maintenance phase. However, removal of AP occurred after a stabilization phase of 8 weeks, during which the patients needed to continue to be responding or be in remission to be eligible for the maintenance phase. Thus, AD and AP were effective and safe for the patients in the trial. The study by Flint et al could therefore be described to be enriched for patients who benefit from AD with AP, a design which tend to increase the effect of the studied drug [Citation22].

In summary, the differences in sample size, acute treatment, and duration of treatment and follow-up time make it questionable to synthesize the high-quality study by Flint et al. with the other two in a meta-analysis. However, the study by Flint et al. only answers the question of whether a patient that has responded to acute treatment with olanzapine and sertraline should continue to receive the same treatment. The everyday clinical setting is more complex, consisting of patients that have responded to a variety of acute treatment modalities such as ECT or AD monotherapy. It is uncertain if the findings of Flint et al. can be generalized to these populations. Thus, we aimed to synthesize the results from studies examining the same maintenance treatment intervention under various conditions, in order to see if we could obtain a more general conclusion.

Regarding other possible interventions, we only identified one controlled study each for AP monotherapy and ECT (+ nortriptyline), and thus no general conclusions can be made about these interventions.

The potential preventive effect of AP as a maintenance treatment for unipolar depression as a whole is uncertain. In a systematic review for patients with non-psychotic unipolar depression by Chen et al. three studies where found, comparing AP monotherapy with placebo; or comparing AP as an adjunctive to AD with AD and placebo [Citation23–26]. The time-to-relapse tended to be longer in patients receiving AP treatment than in the placebo group, but only the study by Liebowitz et al. showed a statistically significant difference [Citation26]. The study by Liebowitz et al. showed that continued quetiapine treatment was advantageous over placebo in patients stabilized on quetiapine. In summary, there are not enough studies on the potential preventive effect of AP in psychotic depression to draw any conclusions. Further research is needed to explore this understudied field, particularly for psychotic depression but also for non-psychotic depression. Treatment with AP is not unproblematic. Except for known side effects of AP such as metabolic effects, extrapyramidal symptoms, and anticholinergic symptoms, AP have also been found to be frequently used agents in suicidal poisoning; thus, if AP does not have a preventive effect, they could potentially be harmful [Citation27,Citation28]. An interesting question is whether there are any differences between different classes of antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics has a reduced risk of extrapyramidal symptoms and also potential antidepressant qualities [Citation29]. We did not find any controlled studies that compared different classes of antipsychotics, nor did Wijkstra et al. in their systematic review on acute pharmacological treatment for psychotic depression [Citation7]. However, this may be an important topic for future research.

ECT is an effective acute treatment for psychotic depression. The American Psychiatric Association recommends ECT as a first-line acute treatment option [Citation8]. There is long clinical experience with ECT for psychotic depression. The scientific basis for this recommendation is largely based on a meta-analysis on acute treatment by Parker et al. comparing ECT, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and AP either as monotherapy or in combination [Citation3]. In this meta-analysis, ECT was superior to TCA monotherapy, and there was a trend for ECT to be superior to TCA + AP combination therapy and AP monotherapy; yet 20 of the 21 included studies on ECT appeared to be uncontrolled studies. To our knowledge there is no systematic review on acute treatment for psychotic depression with controlled studies on pharmacological treatment versus ECT. However, our study group recently conducted a study comparing the suicide frequency among patients with psychotic depression receiving ECT and not receiving ECT. Based on Swedish registries, we matched 1314 inpatients receiving ECT as acute treatment with 1314 not receiving ECT. When adjusting for several factors, including treatment with antidepressants and lithium, there was a markedly decreased risk of suicide among patients receiving ECT with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.20 (95% CI: 0.08–0.54) [Citation30]. We only identified one small controlled study on maintenance treatment with ECT, by Navarro et al. It presented promising results in favor of ECT: only 1/12 patients on ECT and nortriptyline treatment relapsed, compared with 8/13 patients treated with nortriptyline alone, and in this study the patients were followed-up for 2 years. However, the drop-out rate from the analysis in each treatment group was high (23.5% for ECT and nortriptyline and 25% for nortriptyline alone), and the authors concluded that their findings should be interpreted as preliminary. In contrast to the above study, a study by Kellner et al. did not find any statistically significant difference between continuation ECT and combination therapy with nortriptyline and lithium as maintenance treatment [Citation31]. We did not include this study since the results for patients with psychotic unipolar depression were not reported separately from the results for patients with non-psychotic unipolar depression. The study included 31 patients with psychotic unipolar depression receiving ECT monotherapy and 35 patients with psychotic unipolar depression receiving nortriptyline and lithium, after having achieved remission with acute ECT treatment. At the end of the study at 6 months, 37.1% of patients relapsed in the ECT group, and 31.6% relapsed in the nortriptyline and lithium group, for the sample as a whole containing both psychotic unipolar depression and non-psychotic unipolar depression patients; but the authors concluded that the effect of treatment on relapse was not significantly affected by the presence of psychotic symptoms.

Lithium, the gold standard for maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder [Citation32], seems to be effective to prevent relapse in unipolar depression as well. Undurraga et al. conducted a meta-analysis, identifying 21 RCT studies on long-term treatment with lithium in unipolar depression [Citation33]. The pooled results favored lithium over placebo or other comparators with an OR of 2.80 (95% CI: 1.59–4.92). Lithium also seems to be effective to prevent relapse after successful acute ECT treatment. Lambrichts et al. recently conducted a meta-analysis, including 14 studies on maintenance treatment with lithium after an acute course of ECT in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression. Patients treated with lithium were at lower risk of suffering a relapse compared to patients not receiving lithium, with a weighted OR of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.34–0.82) [Citation34]. Also, maintenance treatment with lithium reduces suicide rates in unipolar depression [Citation35], although we are not aware of any studies on the effects of lithium to prevent suicide specifically in psychotic depression. Thus, more studies are needed on lithium as maintenance treatment for psychotic depression.

The major limitation of this review is that we only identified seven controlled studies (of which five were included), and most of these studies had few participants and few events. There is not just a lack of studies on maintenance treatment, but also on acute treatment. In the abovementioned systematic review on acute pharmacological treatment by Wijkstra et al. they identified 12 RCTs with a total of 929 participants. Their results showed superiority of AD + AP combination therapy over AD monotherapy. However, they stated that this area was heavily understudied. They mention that it is very difficult to conduct RCTs for this population, and that these patients often are unable or reluctant to give informed consent [Citation7]. The inability to give informed consent may be due to the severity of this subtype of depression. Except for having psychotic symptoms, some studies are suggesting that also the depressive symptoms are more severe and that these patients have a higher number of hospitalizations than patients with non-psychotic depression [Citation2,Citation36].

It seems unlikely that the same problem applies to studies on maintenance treatment, since the patients usually need to have few or no symptoms to be eligible to enter a study. If there are difficulties to recruit patients due to the nature of psychotic depression one may have to depend on more limited small sampled studies. Except for the statistical uncertainty, small studies are also limited for testing hypotheses on other potentially influencing factors. Comorbidity may for instance be a factor that might complicate treatment response. In a study by Souery et al. comorbidity with panic disorder, social phobia, and personality disorders were associated with remaining depressive symptoms after pharmacological treatment in patients with major depressive disorder [Citation37]. The majority of the studies we included in this review do not have enough patients to analyze a possible effect of these comorbidities on relapse rates with different maintenance treatments. A complementary approach is to conduct large registry-based observational studies to address these questions.

Another limitation of our review is that after having selected abstracts from the initial screening process, four non-English articles were excluded, which may have added further evidence (although based on their abstracts, two of these studies were small; each had 21 patients or fewer) [Citation38,Citation39].

Finally, there were difficulties in assessing a potential publication bias when comparing AD + AP combination therapy with AD monotherapy. Since we only identified three studies, it was not possible to construct a funnel plot [Citation11]. We conducted a comprehensive search, minimizing the risk of not detecting studies with negative/null findings. Also, in the study by Flint et al. we found no evidence for lag bias (i.e. early publication of positive results). Their final follow-up date was 13 June 2017, and the study was not published until 20 August 2019. In summary, although the means to determine an eventual publication bias were limited, we decided that there was not enough evidence of publication bias to cause downgrading of the final GRADE score.

In conclusion, we only identified the comparison between AD + AP combination therapy versus AD monotherapy to have more than one conducted study, but there was no statistically significant difference between these interventions in the meta-analysis. The clinical interpretation of the weak evidence base is not easy. We primarily suggest to continue the same treatment that induced remission, regardless if this treatment was AD + AP, AD monotherapy or ECT. Because ECT requires many resources, to gradually taper ECT in favor of lithium could be a more practical possibility [Citation34,Citation40]. However, one should be aware that these suggestions are based on very limited evidence, which highlights the need for further controlled studies.

We did not find any studies on maintenance treatment for psychotic bipolar depression, and it is unclear whether the studies on unipolar psychotic depression can be generalized to this patient population, especially regarding treatment with AD. There is an ongoing debate on whether AD is efficacious and safe to use in patients with bipolar depression without psychosis [Citation41–43]. The same controversy may apply to the treatment of psychotic bipolar depression, but further studies are needed to address this question.

Geolocation information

This study was conducted in Sweden.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (49.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.1 KB)Disclosure statement

Axel Nordenskjöld has received a lecturer honorarium from Lundbeck.

Data availability statement

All relevant data are presented in the article and supplementary material.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Al-Wandi

Ahmed Al-Wandi, MD, is a resident physician in psychiatry and a PhD-student at School of Medical Sciences, Örebro University, Sweden.

Christoffer Holmberg

Christoffer Holmberg, BSc, is a fifth-year medical student at School of Medical Sciences, Örebro University, Sweden.

Mikael Landén

Mikael Landén, MD, PhD is a psychiatrist. He is a professor of psychiatry at the Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

Axel Nordenskjöld

Axel Nordenskjöld, MD, PhD is a psychiatrist at the Unit for brain stimulation, University Hospital Örebro. He is an associate professor at the Faculty of Medicine and Health, Örebro University, Sweden.

References

- Jääskeläinen E, Juola T, Korpela H, et al. Epidemiology of psychotic depression – systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):905–918.

- Lykouras L, Gournellis R. Psychotic (delusional) major depression: new vistas. CPSR. 2009;5(1):1–28.

- Parker G, Roy K, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Psychotic (delusional) depression: a meta-analysis of physical treatments. J Affect Disord. 1992;24(1):17–24.

- Petrides G, Fink M, Husain MM, et al. ECT remission rates in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients: a report from CORE. J Ect. 2001;17(4):244–253.

- Pande AC, Grunhaus LJ, Haskett RF, et al. Electroconvulsive therapy in delusional and non-delusional depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 1990;19(3):215–219.

- Farahani A, Correll CU. Are antipsychotics or antidepressants needed for psychotic depression? A systematic review and Meta-analysis of trials comparing antidepressant or antipsychotic monotherapy with combination treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(04):486–496.

- Wijkstra J, Lijmer J, Burger H, et al. Pharmacological treatment for psychotic depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):Cd004044.

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2010.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Jadad AR, Moore RA ,Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12.

- Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al, editors. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group. 2013. Available from guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook

- Shiwaku H, Fujita M, Takahashi H. Benzodiazepines reduce relapse and recurrence rates in patients with psychotic depression. JCM. 2020;9(6):1938–1910.

- Birkenhager TK, Van Den Broek WW, Mulder PGH, et al. One-year outcome of psychotic depression after successful electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2005;21(4):221–226.

- Flint AJ, Meyers BS, Rothschild AJ, et al. Effect of continuing olanzapine vs placebo on relapse among patients with psychotic depression in remission: the STOP-PD II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(7):622–631.

- Meyers BS, Klimstra SA, Gabriele M, et al. Continuation treatment of delusional depression in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):415–422.

- Wijkstra J, Burger H, van den Broek WW, et al. Long-term response to successful acute pharmacological treatment of psychotic depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;123(1–3):238–242.

- Bingham KS, Meyers BS, Mulsant BH, et al. Stabilization treatment of remitted psychotic depression: the STOP-PD study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(3):267–273.

- Navarro V, Gasto C, Torres X, et al. Continuation/maintenance treatment with nortriptyline versus combined nortriptyline and ECT in late-life psychotic depression: a two-year randomized study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(6):498–505.

- Meyers BS, Flint AJ, Rothschild AJ, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of olanzapine plus sertraline vs olanzapine plus placebo for psychotic depression: the study of pharmacotherapy of psychotic depression (STOP-PD). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):838–847.

- Rothschild AJ, Duval SE. How long should patients with psychotic depression stay on the antipsychotic medication? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(4):390–396.

- Naz B, Craig TJ, Bromet EJ, et al. Remission and relapse after the first hospital admission in psychotic depression: a 4-year naturalistic follow-up. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1173–1181.

- Rabinowitz J, Werbeloff N, Mandel FS, et al. Determinants of antidepressant response: Implications for practice and future clinical trials. J Affect Disord. 2018;239:79–84.

- Chen J, Gao K, Kemp DE. Second-generation antipsychotics in major depressive disorder: update and clinical perspective. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24(1):10–17.

- Rapaport MH, Gharabawi GM, Canuso CM, et al. Effects of risperidone augmentation in patients with treatment-resistant depression: results of open-label treatment followed by double-blind continuation. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;31(11):2505–2513.

- Alexopoulos GS, Canuso CM, Gharabawi GM, et al. Placebo-controlled study of relapse prevention with risperidone augmentation in older patients with resistant depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):21–30.

- Liebowitz M, Lam RW, Lepola U, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy as maintenance treatment of major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(10):964–976.

- Longden E, Read J. Assessing and reporting the adverse effects of antipsychotic medication: a systematic review of clinical studies, and prospective, retrospective, and cross-sectional research. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(1):29–39.

- Mainio A, Kuusisto L, Hakko H, et al. Antipsychotics as a method of suicide: population based follow-up study of suicide in Northern Finland. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75(4):281–285.

- Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):365–373.

- Rönnqvist I, Nilsson FK, Nordenskjöld A. Electroconvulsive therapy and the risk of suicide in hospitalized patients with major depressive disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116589.

- Kellner CH, Knapp RG, Petrides G, et al. Continuation electroconvulsive therapy vs pharmacotherapy for relapse prevention in major depression: a multisite study from the consortium for research in electroconvulsive therapy (CORE). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(12):1337–1344.

- Hirschowitz J, Kolevzon A, Garakani A. The pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder: the question of modern advances. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010;18(5):266–278.

- Undurraga J, Sim K, Tondo L, et al. Lithium treatment for unipolar major depressive disorder: Systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(2):167–176.

- Lambrichts S, Detraux J, Vansteelandt K, et al. Does lithium prevent relapse following successful electroconvulsive therapy for major depression? A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143(4):294–306.

- Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, et al. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646.

- Coryell W. The treatment of psychotic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 1:22–27. discussion 8–9.

- Souery D, Oswald P, Massat I, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment resistance in major depressive disorder: results from a european multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(07):1062–1070.

- Serra M, Gasto C, Navarro V, et al. [Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy in elderly psychotic unipolar depression]. Med Clin (Barc). 2006;126(13):491–492.

- Snedkova LV. [A trial of the use of nifedipine for preventing relapses in affective and schizoaffective psychoses]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 1996;96(1):61–66.

- Brus O, Cao Y, Hammar Å, et al. Lithium for suicide and readmission prevention after electroconvulsive therapy for unipolar depression: population-based register study. BJPsych Open. 2019;5(3):e46.

- Gijsman HJ, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, et al. Antidepressants for bipolar depression: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(9):1537–1547.

- Viktorin A, Lichtenstein P, Thase ME, et al. The risk of switch to mania in patients with bipolar disorder during treatment with an antidepressant alone and in combination with a mood stabilizer. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(10):1067–1073.

- Sidor MM, Macqueen GM. Antidepressants for the acute treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(02):156–167.