Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) has been associated with increased risk of mortality in large register samples. However, there is less known about the association between symptoms of ADHD in adolescents and risk of mortality in general population samples.

Methods

The Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986 (n = 9432 at recruitment in early pregnancy) linked to nationwide register data for deaths was utilized to study the association between parent-rated ADHD symptoms assessed using Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD symptoms and Normal Behaviors (SWAN) questionnaire and mortality until age 33 years. Cox-regression analysis with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to study the association between SWAN inattentive, hyperactive, and combined symptom scores and risk of death.

Results

Sixty-three (0.9%) of the 6685 participants died during the follow-up. Higher SWAN inattentive (crude HR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.46–3.63), SWAN hyperactive (crude HR = 2.43, 95% CI 1.29–4.56), and SWAN combined (crude HR = 2.69, 95% CI 1.57–4.61) scores were associated with increased risk of death. After adjustments for sex, family structure, and lifetime parental psychiatric disorder, these associations persisted. Further adjustment for frequent alcohol intoxication, cannabis, and other substance use in adolescence attenuated these to below statistical significance.

Conclusions

These results extend previous findings on the risk of mortality in adolescents who have symptoms of ADHD. Further research with larger samples are needed to determine whether the association between ADHD symptoms and mortality is independent of adolescent substance use.

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurobehavioral disorder characterized by age-inappropriate levels and persistent patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity with onset prior to age of 12 [Citation1]. The community prevalence of ADHD is 5.9% in youths and 2.5% in adults and is more common in males [Citation2]. Recent longitudinal study findings indicate that youth with ADHD continue to display fluctuating, yet persistent, levels of ADHD symptoms and social functioning impairments through young adulthood [Citation3].

ADHD is associated with excess mortality that has been linked to psychiatric comorbidity (e.g. substance use disorder (SUD) and conduct disorder) in large nationwide register studies due to suicide, unintentional injury, and external causes [Citation4–10]. However, the association with mortality has not been studied using prospective general population cohorts and covering the full spectrum of ADHD symptoms, i.e. including those not meeting the threshold for diagnosis. This is important as ADHD symptoms at a subthreshold level have been related to significant impairment [Citation11,Citation12].

Individuals with diagnosed ADHD or ADHD symptoms are more likely to show a pattern of early substance use [Citation13–17]. Prospective general population studies report a link between frequent alcohol intoxication [Citation18], stimulant [Citation19] and cannabis use [Citation20] in adolescence and excess mortality. Thus, adolescent onset substance use behaviors could plausibly explain the association between ADHD and mortality.

The Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986 (NFBC 1986) [Citation21] is a large prospective general population-based study that is linked to multiple Finnish national registers covering data on mortality. NFBC 1986 provides data on a range of potential covariates such as adolescent substance use and demographic factors. Use of this cohort allowed us to test whether ADHD symptoms at age 16 years were associated with all-cause mortality up until age of 33. Furthermore, we tested whether these associations were independent of demographic factors, parental psychiatric disorder, and adolescent substance use.

Methods

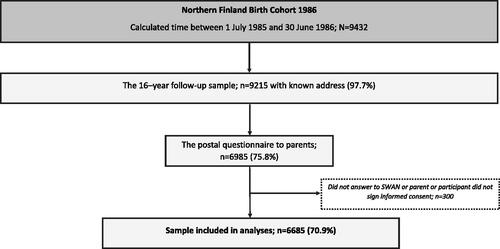

NFBC 1986 is an ongoing follow-up study including 99% of all live-born children (n = 9432) with an expected date of birth between 1 July 1985 and 30 June 1986, from the two northernmost provinces in Finland. Data used in these analyses were collected between 2001–2002 when study members were aged 15–16 years. First, participants and their parents with valid addresses were sent self-report questionnaires in separate envelopes (n = 9215); we received 7344 completed postal questionnaires from adolescents and 6985 from their parents. The adolescent answered questions e.g. concerning their physical health and psychosocial wellbeing. Their parents completed the Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD symptoms and Normal Behaviors (SWAN) questionnaire [Citation22] for their offspring (n = 6985) and answered questions concerning family and demographic factors. Second, adolescent participants were invited to attend a clinical study, where they completed a self-report that included e.g. questions on substance use (n = 6798). Participants and parents who signed the informed consent form with available data on ADHD symptoms were included in the study. Using these data, cohort participants were followed-up for 17 years from 2001 until 2018. The final sample totaled 6685 individuals. For data flow, see .

NFBC 1986 study is approved by the Ethics committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District in Finland with latest version dated on 15.1.2018 (EETTMK 108/2017). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Mortality by age 33 years

Data on dates and causes of death were obtained from national registers Population Register Data and Registry for Causes of Death that cover all the deaths in Finland. These data were available until the end of 2018 i.e. until the participants were at age of 33 years. The deaths were categorized into those due to somatic causes, accidents and suicide according to International Classification of Disease 10th revision and these data were combined to reflect all-cause mortality.

ADHD symptoms at age 15/16 years

The Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD symptoms and Normal Behaviors (SWAN) questionnaire [Citation22] is a revised version of the SNAP-IV developed by Swanson and his colleagues measuring problems in attention, hyperactivity/impulsivity and disruptive behavior [Citation22]. Parents rated items based on the 18 ADHD symptoms described in the DSM-IV-TR for example ‘Gives close attention to detail and avoids careless mistakes’. Parents rate these items on a seven-point scale anchored to average behavior (i.e. Far Below Average = 3, Below Average = 2, Somewhat Below Average = 1, Average = 0, Somewhat Above Average = −1, Above Average = −2, and Far Above Average = −3) resulting in normally distributed behavioral traits. Swanson suggested that collapsing the −3 to −1 ratings into the zero category yielded similar distribution of individuals as the SNAP 0–3 rating scale and this categorization has been used in NFBC studies on ADHD [Citation23,Citation24]. As the aim of this study was to test the association between ADHD symptoms and mortality, the −3 to −1 ratings were collapsed into zero category. Individual SWAN items were used to compute means for a Combined scale score (C), using all 18 items, an Inattentive score (I) using 9 Inattentive items, and a Hyperactive-Impulsive score (HI) using 9 Hyperactive-Impulsive items. We excluded participant data if the SWAN scales had more than one item missing. If there was only one item missing, the missing value was replaced by the mean value of the items of the particular scale for that person. For the questionnaire used in this study, see NFBC website: https://www.oulu.fi/nfbc/node/18149.

Adolescent substance use (age 15/16 years)

Participants self-reported their frequency of alcohol intoxication during the past year. Participants were asked: ‘Have you been drunk during the past year? (0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–39, or 40 times or more)’. We dichotomized this variable as ≥10 times (=1) and ≤9 (=0) based on the distribution of data.

To assess cannabis use up until follow-up, participants were asked: ‘Have you used marihuana or hashish?’ with options ‘never’, ‘once’, ‘two to four times’, ‘five or more times’, or ‘I use regularly’. These options were pooled as ‘adolescent lifetime cannabis use’ yes (=1) or no (=0) to provide sufficient sample size.

Adolescents were also asked ‘Have you tried or used any of the following substances? – Ecstasy, heroin, cocaine, amphetamine, LSD or other similar intoxicating drugs?’ and ‘Have you ever tried or used any of the following substances? - Sniffing thinner, glue, etc. for intoxication’ with options ‘never’, ‘once’, ‘two to four times’, ‘five or more times’, or ‘I use regularly’. The data on other illicit substances other than cannabis and use of inhalants were pooled into a binary variable ‘other lifetime substance use’ yes (=1) or no (=0) to provide sufficient sample size.

Family structure

Information on family structure was collected by combining data from parents at birth and from the clinical study in 2001–2002. These data were categorized as ‘family with two biological parents (=1)’, where both biological parents lived together with the participant, and ‘other (=0)’, which consisted of all other family types.

Parental psychiatric disorders

Data on parental psychiatric diagnoses (F00–69, F80–99) were obtained up until 2018 from the national registers, which included: (1) Register of Health Care 1972–2018 (including inpatient care and visits to specialized outpatient health care since 1998), (2) Disability pensions of the Finnish Centre for Pensions (1965–2016), and (3) The Register of Primary Health Care Visits (2011–2018). For more information about the registers, see a previous study [Citation25]. The Finnish national register data are generally reliable [Citation26] and are more complete as compared to surveys [Citation27].

Statistical methods

We used χ2 or Fisher exact test to assess the relationship of covariates and death during follow-up. The associations between means on each of the three SWAN subscales (inattentive, hyperactive, and combined), treated as continuous variables, with all-cause mortality were examined using Cox-regression analysis with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) as Model 1. To study whether the association between adolescent ADHD symptoms and mortality is independent of potentially confounding factors, we included frequent alcohol intoxication [Citation18], substance use [Citation13–15] parental psychiatric disorders [Citation28,Citation29], sex [Citation4], and family structure [Citation30] as covariates. We adjusted for covariates as follows: Model 2: sex, family structure, and parental psychiatric disorder. Model 3 additionally included frequency of alcohol intoxication during the past year, adolescent lifetime cannabis use and adolescent lifetime substance use other than cannabis. The HR reflect risk of death by unit increase in SWAN scale. Statistical significance was considered when p ≤ .05. Linear regression and multicollinearity diagnostics with variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were used to examine possible correlation between multiple covariates (variables in Model 3).

There is known attrition in this sample such that fewer males (64% vs. 71%; p < .001), individuals living in urban areas (66% vs. 71%, p < .001) and individuals with parental psychiatric disorder (58% vs. 69%, p < .001) participated in the 15–16 year follow-up study [Citation31]. To address attrition due to non-participation, we weighted our crude analyses by sex, parental psychiatric disorder, and urbanicity by using inverse probability weighting [Citation32] and analyzed these data with logistic regression analysis and odds ratios (OR).

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25; IBM Co., Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

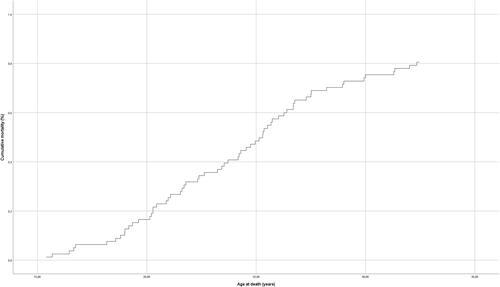

The final sample included 6685 (49.9% male) participants. Cumulatively, 63/6685 (0.9%) deaths occurred during the 17-year follow-up. Of these, 46 died due to non-natural causes (27 suicides, 19 unintentional injury or external causes) and 17 due to natural causes. As shown in , those who died during the follow-up period, i.e. adolescence to age 33 years, had generally higher SWAN means scores, were more likely to be male, come from families where both biological parents did not live with the participant, and were also more likely to live in families with parental psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, they were also more likely to report adolescent lifetime cannabis and other substance use and frequent alcohol intoxication past year. Multicollinearity was not seen (all VIFs < 1,2). Hazard curve for the NFBC1986 follow-up sample is presented in .

Table 1. Demographics of the sample.

In the crude analyses (Model 1) higher SWAN inattentive (HR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.46–3.63), SWAN hyperactive (HR = 2.43, 95% CI 1.29–4.56), SWAN combined (HR = 2.69, 95% CI 1.57–4.61) were associated with risk of death at a statistically significant level. After adjustments for sex, family structure, and parental psychiatric disorder (Model 2), the associations with SWAN inattentive, hyperactive, and combined remained statistically significant (see ). Further adjustment for frequent alcohol intoxication in the previous year and adolescent lifetime cannabis use and other substances (Model 3) attenuated all associations to statistically nonsignificant level (see ). In these final models, frequent alcohol intoxication, parental psychiatric disorder, and male sex were associated with all-cause mortality (online supplement Table 1). There was substantial non-response concerning substance use items that limited sample sizes. This resulted in selective attrition as 1.6% (18/1097) of those who did not answer substance use items deceased during the follow-up compared to 0.8% (44/5432) of those in Model 3.

Table 2. Association of ADHD symptoms and mortality in Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986.

All the statistically significant ORs in unweighted analyses were also statistically significant in the weighted analyses, and the strength of the associations were of similar magnitude (see online supplement tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

In this population-based sample of Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1986, we report positive linear associations between parent-rated ADHD (Hyperactive and Inattentive and Combined) symptoms in adolescence and increased mortality risk in the following 17 years. The association of inattentive, hyperactive, and combined symptoms and mortality risk remained after adjustment for sex, family structure, and parental psychiatric disorder. Additional adjustments for frequent alcohol intoxication during the past year, cannabis use, and other substance use in adolescence attenuated the associations to statistically non-significant. However, there was selective attrition 29% of individuals who died during the follow-up had missing values on substance use items. This may account for the attenuation of the associations to statistical non-significance.

Our findings are in line with previous large nationwide register studies where ADHD diagnosis has been associated with excess mortality [Citation4–8]. These studies have examined unnatural (accidents, injury, and suicide) and natural causes of death and have reported increased mortality for unnatural causes. Our study, using NFBC a general population-based birth cohort, is able to include variables gathered across the life course on lifestyle characteristics and to link this information to the national register of causes of death. Thus, in contrast to previous population-register studies with larger sample sizes, our study has the advantage of providing detailed data on potential covariates. Although mortality in this age range was rare with only 63 (9.4 deaths per 1000) participants deceased during the follow-up period, our study was able to provide novel evidence of a link between ADHD symptoms in adolescence and increased risk of death by the age of 33 years.

This study utilized data on ADHD symptoms reported by parents from all consenting participants and focused on these symptom dimensions in the general population. Thus, extending the existing register studies [Citation4–8] to study ADHD at the symptom-level. These findings are important as they pertain to the general population with ADHD symptoms and not restricted to the most severe cases warranting ADHD diagnosis. Our findings are further supported by results from a recent study where a high polygenetic predisposition to ADHD increased the risk of all-cause mortality [Citation33]. Together these findings suggest that ADHD liability/severity may increase risk of death linearly. More studies are warranted to examine the association between ADHD symptoms and mortality risk due to the public health significance of the present findings and need for adequate prevention strategies.

Adjustment for alcohol intoxication and substance use, however, attenuated the associations. In some of the previous studies, the association of ADHD diagnosis and all-cause mortality has persisted beyond adjustment for comorbidities such as substance use disorders [Citation5,Citation6]. We believe that due to selective attrition, this study is not able to determine if the associations between ADHD symptoms and mortality are to some extent explained by alcohol intoxication or cannabis use. This is an important issue as substance use in adolescence has been associated with premature death and at the same time ADHD diagnosis and ADHD symptoms have been reported to increase the likelihood of using different substances. Thus, we emphasize caution when interpreting these findings and further studies are needed to disentangle and directly test whether the association is influenced by alcohol intoxication or substance use and if so, to what extent.

Strengths and limitations

The NFBC 1986 study sample is one of the largest birth cohort studies with high genetic and ethnic homogeneity and considerable follow-up allowing for robust examination of life-course factors. This study was able to examine the associations between ADHD symptoms and mortality in the general population by combining questionnaire data with national registers for death and psychiatric disorders using a prospective design. The linkage of several national registers provides objective data with high coverage on deaths during the 17-year follow-up. Furthermore, the extensive dataset allowed us to examine the associations while including potential confounders.

There are also limitations. Even with considerable sample size, death in this age range is a rare outcome and thus we were not able to study the specific causes of death. Adolescent lifetime substance use was collected via self-report at age 15–16 and may be underreported. Specific non-response to the substance use items limited the sample size further. This introduces risk of type 2 error in adjusted models. Female sex has been associated with greater ADHD related mortality [Citation4,Citation6], but we were not able stratify our sample by sex due to power issues. There was significant non-participation in 2001–2002 follow-study, but weighted analyses corresponded to the unweighted analyses thus providing some confidence in validity of results. Finally, possible role of childhood or familial adversity could not be accounted for, and residual confounding such as symptoms of comorbid disruptive behavioral disorders may persist [Citation10]. However, we were able to use data on family history of psychiatric disorders to account for possible environmental and genetic confounding arising from parental psychiatric disorders.

Conclusions

In this general population-based birth cohort sample of 6685 individuals followed for 17 years via data linkage to national registers, we report a positive linear association between ADHD symptoms in adolescence and risk of death by the age of 33 years. This extends the literature on mortality to adolescents not necessarily meeting the criteria for ADHD diagnosis. Future studies with sufficiently large sample sizes should directly test whether this association is influenced by adolescent substance use.

Author contributions

AM and SN developed conception and design of the work. AM, SN, and AEA performed data analysis and interpretation. AM, SN, JM, MV, AR, TH, AHH, and JGS wrote the first manuscript draft. AM, SN, JM, AR, MV, TH, AHH, JGS, and AEA supervised conception and design of the work and provided critical revision of the article. All authors contributed approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank all cohort members and researchers who have participated in the study. We also wish acknowledge the work of the NFBC project center. We thank statistician Jari Koskela for his help.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

NFBC data is available from the University of Oulu, Infrastructure for Population Studies. Permission to use the data can be applied for research purposes via electronic material request portal. In the use of data, we follow the EU general data protection regulation (679/2016) and Finnish Data Protection Act. The use of personal data is based on cohort participant’s written informed consent at his/her latest follow-up study, which may cause limitations to its use. Please contact NFBC project center ([email protected]) and visit the cohort website (www.oulu.fi/nfbc) for more information.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antti Mustonen

Antti Mustonen, MD, PhD, is a post-doctoral researcher at Faculty of Medicine and Health Technology, Tampere University and Center for Life Course Health Research, University of Oulu and a psychiatry resident in Department of Psychiatry, Seinäjoki Central Hospital.

Anni-Emilia Alakokkare

Anni-Emilia Alakokkare, MSc, is a statistician at Center for Life Course Health Research, University of Oulu and Department of Psychiatry, University of Turku.

James G. Scott

James G. Scott, MD, PhD is a professor and leads the Child and Youth Research Group at the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute. He also practices clinically as a Child and Youth Psychiatrist with the Metro North Mental Health Service, where he is the Director of the Early Psychosis Service.

Anu-Helmi Halt

Anu-Helmi Halt MD, PhD, is a clinical lecturer and a post-doctoral researcher at Research Unit of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry, University of Oulu and a co-PI in the follow-up study of ADHD in NFBC1986. She also works as a psychiatrist and as a cognitive psychotherapist in Oulu University Hospital.

Miika Vuori

Miika Vuori, RMN, PhD, is a senior researcher at Research Centre for Child Psychiatry, University of Turku. Tuula Hurtig, PhD, is an associate professor and a university lecturer at Research Unit of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry, University of Oulu, PEDEGO Research Unit, Child Psychiatry, University of Oulu and Clinic of Child Psychiatry, Oulu University Hospital.

Alina Rodriguez

Alina Rodriquez, PhD, is professor of psychology working in public health at the junction of mental and physical health. She is affiliated with Imperial College London and Queen Mary University of London.

Jouko Miettunen

Jouko Miettunen, PhD, is a professor at Center for Life Course Health Research, University of Oulu. Solja Niemelä, MD, PhD is an associate professor at Department of Psychiatry, University of Turku and senior physician at Addiction Psychiatry Unit, Turku University Hospital.

References

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5TM. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2013.

- Faraone SV, Banaschewski T, Coghill D, et al. The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:789–818.

- Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. American J Psychiatry 2022;179(2):142–151.

- Dalsgaard S, Ostergaard SD, Leckman JF, et al. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2190–2196.

- Sun S, Kuja-Halkola R, Faraone SV, et al. Association of psychiatric comorbidity with the risk of premature death among children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(11):1141–1149.

- Chen VCH, Chan HL, Wu SI, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mortality risk in Taiwan. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198714.

- Fitzgerald C, Dalsgaard S, Nordentoft M, et al. Suicidal behaviour among persons with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(4):615–620.

- London AS, Landes SD. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and adult mortality. Prev Med. 2016;90:8–10.

- Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, et al. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76.

- Scott JG, Giørtz Pedersen M, Erskine HE, et al. Mortality in individuals with disruptive behavior disorders diagnosed by specialist services - a nationwide cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:255–260.

- Kirova AM, Kelberman C, Storch B, et al. Are subsyndromal manifestations of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder morbid in children? A systematic qualitative review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:75–90.

- Rodriguez A, Järvelin M-R, Obel C, et al. Do inattention and hyperactivity symptoms equal scholastic impairment? Evidence from three European cohorts. BMC Public Heal. 2007;7(1):1–9.

- Molina BSG, Howard AL, Swanson JM, et al. Substance use through adolescence into early adulthood after childhood-diagnosed ADHD: findings from the MTA longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(6):692–702.

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, et al. The role of early childhood ADHD and subsequent CD in the initiation and escalation of adolescent cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123(2):362–374.

- Connolly RD, Speed D, Hesson J. Probabilities of ADD/ADHD and related substance use among Canadian adults. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(12):1454–1463.

- Lee PH, Anttila V, Won H, et al. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2019;179(7):1469.e11–1482.e11.

- Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF, Sigfusdottir ID, et al. An epidemiological study of ADHD symptoms among young persons and the relationship with cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and illicit drug use. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(3):304–312.

- Levola J, Sarala M, Mustonen A, et al. Frequent alcohol intoxication and high alcohol tolerance during adolescence as predictors of mortality: a birth cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(5):692–699.

- Davstad I, Allebeck P, Leifman A, et al. Self-reported drug use and mortality among a nationwide sample of Swedish conscripts – a 35-year follow-up. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118(2-3):383–390.

- Manrique-Garcia E, De Leon AP, Dalman C, et al. Cannabis, psychosis, and mortality: a cohort study of 50,373 Swedish men. AJP. 2016;173(8):790–798.

- University of Oulu. Northern Finland birth cohort 1986; Published online 1986. Available from: http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:att:f5c10eef-3d25-4bd0-beb8-f2d59df95b8e

- Swanson JM, Schuck S, Porter MM, et al. Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: history of the SNAP and the SWAN rating scales. Int J Educ Psychol Assess. 2012;10(1):51–70.

- Lubke GH, Muthén B, Moilanen IK, et al. Subtypes versus severity differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the Northern Finnish birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(12):1584–1593.

- Khalife N, Kantomaa M, Glover V, et al. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms are risk factors for obesity and physical inactivity in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(4):425–436.

- Filatova S, Marttila R, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, et al. A comparison of the cumulative incidence and early risk factors for psychotic disorder in young adults in the Northern Finland birth cohorts 1966 and 1986. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(3):314–324.

- Sund R. Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):505–515.

- Haapea M, Miettunen J, Isohanni MK, et al. Non-participation in a field survey with respect to psychiatric disorders. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(7):728–736.

- Ranning A, Benros ME, Thorup AAE, et al. Morbidity and mortality in the children and young adult offspring of parents with schizophrenia or affective disorders-a nationwide register-based cohort study in 2 million individuals. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(1):130–139.

- Björkenstam E, Björkenstam C, Jablonska B, et al. Cumulative exposure to childhood adversity, and treated attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a cohort study of 543 650 adolescents and young adults in Sweden. Psychol Med. 2018;48(3):498–507.

- McAdams TA, Neiderhiser JM, Rijsdijk FV, et al. Accounting for genetic and environmental confounds in associations between parent and child characteristics: a systematic review of children-of-twins studies. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(4):1138–1173.

- Miettunen J, Murray GK, Jones PB, et al. Longitudinal associations between childhood and adulthood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology and adolescent substance use. Psychol Med. 2014;44(8):1727–1738.

- Haukoos JS, Newgard CD. Advanced statistics: missing data in clinical Research-Part 1: an introduction and conceptual framework. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):662–668.

- Ajnakina O, Shamsutdinova D, Wimberley T, et al. High polygenic predisposition for ADHD and a greater risk of all-cause mortality: a large population-based longitudinal study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):1–10.