Abstract

Background

Little is known regarding the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with both coronary heart disease (CHD) and type D personality, and whether these patients may benefit from psychotherapy that modifies metacognitive beliefs implicated in disorder maintenance. This study explored prevalence rates among these patients and associations between type D characteristics, rumination and metacognitions.

Methods

Forty-seven consecutive patients with CHD who scored positive for type D personality were included in this pre-planned study. Participants underwent structured clinical interviews for mental and personality disorders and completed questionnaires assessing rumination and metacognitions.

Results

Mean age was 53.8 (SD 8.1) years and 21.3% were female. At least one mood disorder or anxiety disorder was found in 70.2% and 61.7% of the patients. The most common disorders were major depressive disorder (59.6%), social phobia (40.4%), and generalized anxiety disorder (29.8%). At least one personality disorder was detected in 42.6%. Only 21% reported ongoing treatment with psychotropic medication whereas none had psychotherapy. Metacognitions and rumination were significantly associated with negative affectivity (0.53–0.72, p < .001) but not social inhibition.

Conclusion

Mood and anxiety disorders were highly prevalent and relatively untreated among these patients. Future studies should test the metacognitive model for type D personality.

Introduction

Type D personality is an established risk factor for the development and poor prognosis of coronary heart disease (CHD) [Citation1], and it is included in the European Cardiovascular Prevention Guidelines as a risk factor to screen for [Citation2]. Type D personality or Distressed personality [Citation3] is ‘characterized by the combination of negative affectivity (NA) and social inhibition (SI)’ [Citation4]. Negative affectivity is the tendency to experience negative emotions across time and situations and is associated with feelings of dysphoria. Social inhibition, or the tendency to inhibit the expression of emotions or behavior, is a major determinant of social distress and is associated with the avoidance of negative reactions from others [Citation4]. Both traits describe psychologically vulnerable individuals and can be assessed using the type D scale or DS14 [Citation3]. The prevalence rates of Type D personality in patients with CHD range from 18% to 53% [Citation5] and most recently it was argued that type D personality should be taken into account in patient-oriented CHD treatment [Citation6].

Given the definition of Type D personality, it is not surprising that it has been associated with symptoms of emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety. Most previous studies examining the associations between Type D personality and emotional disorders have used self-report questionnaires [Citation7]. To date, only three studies have relied on psychiatric diagnostic interviews to explore the link between Type D personality and psychiatric disorders in CHD patients [Citation7–9]. One such study reported a 26% prevalence of depression in a group of patients experiencing myocardial-infarction (MI) who also had Type D personality [Citation8]. In another similar study among patients with MI, psychiatric disorders were significantly more prevalent in patients with Type D compared to those without type D personality, with 40% of the Type D patients identified as suffering from depressive disorders as opposed to 6% among those without type D personality [Citation9]. The association between Type D personality and a broader spectrum of mental disorders was also investigated in 570 patients with depression and CHD. In this study, there was a prevalence of at least one mental disorder in 85% of patients with both type D and CHD, with affective disorders (54%) being the most common cluster of disorders [Citation7]. Finally, at least one personality disorder or dysthymia was found in 30% of this patient group [Citation7]. Despite the high prevalence of mental disorders, we do not know if these patients are identified and offered treatment for their mental disorders.

A principal aim of this study was to contribute to our knowledge of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among patients with Type D personality and CHD by using only clinician-administered psychiatric diagnostic interviews for both mental and personality disorders in an unselected group of CHD patients longer term after the event. Another key aim was to contribute to our understanding of the psychological factors associated with the maintenance of Type D personality by exploring specific associations between Type D personality traits and factors known to be associated with the development and perpetuation of psychopathology [Citation10]. This would enable us to determine effective psychological interventions that can be offered to patients with CHD who are identified as having Type D personality since there is not yet established effective therapies for this important clinical population [Citation1].

To date, there is little knowledge regarding the psychological factors associated with the maintenance of Type D personality. A recent study by Messerli-Burgy and colleagues showed that CHD patients with Type D personality scored significantly higher on a measure of maladaptive emotional regulation than those without Type D personality [Citation11]. Therefore, further knowledge of the maintenance factors associated with Type D personality can be explored within existing influential models of emotional self-regulation. One such model is the metacognitive model of emotional disorders proposed by Wells and based on Wells and Matthews’ Self-Regulatory Executive Function model [Citation12–13]. According to the metacognitive model, ‘people become trapped in emotional disturbance because their metacognitions cause a particular pattern of responding to inner experiences that maintains emotion and strengthens negative ideas’ [Citation12]. This pattern of responding is called the cognitive-attentional syndrome, which consists of perseverative negative thinking such as rumination and worry as well as attentional bias, and unhelpful self-regulatory strategies or coping behaviours. Metacognition is cognition applied to cognition or thinking about thinking or beliefs about thinking. Two sub-types of metacognitive beliefs are positive beliefs about rumination (e.g. ‘I must ruminate in order to find answers to my sadness’) and negative beliefs about rumination (e.g. ‘I cannot control my thinking’). Over the past 30 years, a large volume of research has accumulated supporting the metacognitive model of emotional disorders [Citation9]. In addition, empirical evidence has demonstrated that metacognitive therapy derived from this model is an effective treatment for mood/depressive and anxiety disorders [Citation14–15]. We believe that the state or trait manifestations in Type D personality are the consequences of the cognitive-attentional syndrome, which in turn is activated by maladaptive metacognitive beliefs that can interfere with both the course and medical treatment of CHD.

Grounded on the metacognitive model of emotional disorders, we wanted to explore specific relationships between the cognitive-attentional syndrome (i.e. cognitive perseveration in the form of rumination) and metacognitions relevant for depressive disorders with Type D personality in patients diagnosed with CHD. More specifically, we hypothesized that there would be a significant and positive association between rumination and metacognitions with Type D traits (NA and SI).

Methods

Study design and population

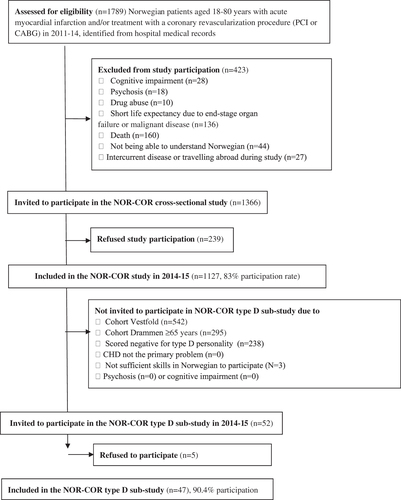

This was a pre-planned sub-study of the Norwegian Coronary (NOR-COR) Prevention Study. The design, methods and baseline characteristics of the NOR-COR Study have been described elsewhere [Citation16] and the study flow chart is shown in . In this cross-sectional study, 1789 consecutive patients aged 18–80 years with first or recurrent diagnosis or treatments for CHD event were retrospectively identified from hospital discharge lists in the past three (i.e. 2011–14) years prior to study participation. The index coronary event was defined as the latest coronary event at the time of study inclusion. A total of 1127 (83%) attended a clinical visit including blood samples and completed a comprehensive questionnaire 2–36 (mean 17) months after the index event [Citation17]. The present sub-study comprised consecutive patients from cohort Drammen aged 18–65 years who scored positive for type D personality and who met all of the additional criteria: (1) CHD was the primary problem, (2) Being able to understand and write the Norwegian language, and (3) Signed written informed consent prior to study entry. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Psychosis as assessed by SCID-I or cognitive impairment, the latter defined as a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score <20 was applied for study exclusion, which is in line with the recommendations of MacKenzie et al. [Citation18]; (2) short life expectancy due to end-stage organ failure or malignant disease; (3) other somatic illness than CHD is experienced as a main somatic problem. We approached 52 consecutive eligible patients in the Drammen cohort of the NORCOR study. Eligible and consenting patients were contacted by the study coordinator and scheduled an appointment for an outpatient consultation with an experienced research psychiatrist at the Department of Medicine, Drammen Hospital and underwent both structured clinical interviews for psychiatric state disorders (SCID-I) [Citation19] and personality disorders (SCID-II) [Citation20], and the completion of self-report questionnaires.

Measures

Demographic and clinical data

Data were obtained from hospital records, clinical measurements, and questionnaires, previously described in detail elsewhere [Citation17]. Socio-demographic factors: age, gender, marital status (single, married or cohabiting, divorced, separated or widowed), work status (part-time, full time, sick leave, rehabilitation, retired, student, unemployed), education (low education was defined as the completion of primary or secondary school only), ethnicity (ethnic minority background defined as 1st and 2nd generation patients born in Asia, Africa or South America) and number of months from index event to follow-up. Medical factors: coronary diagnosis (MI vs. unstable/stable CHD requiring revascularization), number of coronary events prior to index event, cardiovascular risk factors; diabetes, smoking status (current, previous, never), obesity (body mass index >30kg/m2), high blood pressure (>140/90 mmHg or 140/80 mmHg in diabetes), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C in mmol/L), physical activity (low: <30 min of moderate activity 2–3 times/week, no: <1 time/week), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

Self-assessment questionnaires

DS-14 [Citation3] was used for the assessment of type D personality. The scale consists of two 7-item subscales assessing negative affectivity (NA) and social inhibition (SI). Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 to 4. Type D is defined as having a score ≥10 on both the NA and SI subscales. A Norwegian translation version was used that has been validated in a Norwegian group of CHD patients, with acceptable psychometric properties with Cronbach’s α of 87/83 and with a test-retest reliability over a 1-month period of r = 0.91/0.90 for the two subscales, respectively [Citation5,Citation21]. In our study, the alpha for the total scale was 0.89, and those for NA and SI were 0.87 and 0.86, respectively.

Rumination was measured using the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) [Citation22]. The RRS is a 22-item self-report scale that assesses the tendency to ruminate in response to depressed mood and the scores range from 22 to 88. In this study, the alpha for the RRS was 0.96.

Metacognitions were assessed using the Positive Beliefs about Rumination Scale (PBRS) [Citation23–24] and the Negative Beliefs about Rumination Scale (NBRS) [Citation25]. We included these metacognitions because they are more relevant to the metacognitive model of depression [Citation26] since depression is an established risk factor for poor prognosis in CHD patients [Citation27]. The PBRS is a 9-item self-report scale that assesses metacognitive beliefs about the perceived value or usefulness of rumination. Scores range from 9 to 36. In this study, the alpha for the PBRS was 0.92. The NBRS is a 13-item self-report scale designed to assess negative beliefs concerning the perceived uncontrollability and harmfulness of rumination. Scores range from 13 to 52. The alpha for the NBRS was 0.92. For both scales, the higher the score the greater the conviction in the perceived belief.

Diagnostic assessments

All patients underwent the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I (SCID-I) and axis II disorders (SCID-II) [Citation19–20]. It consists of 94 questions that cover the criteria for each of the 10 personality disorders. All diagnostic assessments were confirmed in discussions between the rater and a research clinical psychologist (CP) with extensive experience in diagnostic interviews including SCID-I/P and SCID-II. There was complete agreement in all diagnostic assessments.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with SPSS version 28. Variables are presented as frequencies or mean ± SD. For comparisons within the study groups, the t-test or Mann–Whitney U test (non-normal distribution) was applied for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. All tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was set at p < .05. Pearson’s correlation analyses were conducted.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committee of Ethics in Medical Research (ID number 2013/1885 and 2012/1883b for type D sub-study). All participants signed an informed consent prior to study participation. The NOR-COR study is registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov (ID NCT02309255).

Results

Characteristics

The mean age was 53.8 (SD 8.1) years, 21.3% were female, 96% were native Europeans, 74.4% were married/cohabitant, and 52.3% were currently working. The prevalence of type D personality was 23.1% in the Drammen cohort. Only 25.5% had participated in cardiac rehabilitation. Patients were included on average 18.4 (SD 11.0) months after the index coronary event. The characteristics of the patient group are shown in . We found no significant differences between the type D patients in the present patient group and those who declined participation or were excluded, regarding age, gender and type D characteristics (all ps >0.2).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the included coronary heart disease patients with type D personality <65 years (n = 47).

Prevalence of mental disorders and treatment

Eight out of ten patients suffered from at least one symptom/axis I disorder (). At least one affective disorder was found in 70.2% and at least one anxiety disorder was reported in 61.7% of the patients. Major depressive disorder (59.6%), social phobia (40.4%), and generalized anxiety disorder (29.8%) were the most common disorders. At least one personality disorder was found among 42.6% of the patients, of which avoidant (19.1%), paranoid (19.1%) and obsessive-compulsive (17.0%) personality disorders were the most commonly occurring. Only eight out of 38 patients (21%) with an axis I disorder reported ongoing treatment with psychotropic medication, all reported the use of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), and none reported ongoing psychological treatment. Only six (21.4%) of 32 patients with current major depressive disorder reported ongoing treatment with SSRI.

Table 2. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of chronic coronary heart disease patients with type D personality < 65 years (n = 47).

Associations between Type D characteristics and metacognitions

Correlations between Type D characteristics, rumination and metacognitions are shown in . All metacognitions correlated significantly with the Negative Affectivity (NA) subscale but not the Social Inhibition (SI) subscale. Particularly strong and significant associations were found between NA, rumination, and metacognitions.

Table 3. Zero-order correlations between Type D traits, rumination and metacognitions. Pearson’s r.

Discussion

This pre-planned cross-sectional study among chronic CHD outpatients with type D personality revealed high prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders that were mainly untreated. High correlations were found between rumination, metacognitions and negative affectivity, but not social inhibition.

Our findings of high prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders are consistent with those reported in previous studies [Citation7–9]. We found a higher rate of depressive disorders than that reported in 50 type D patients 2–6 months after a MI [Citation9] and among CHD patients with depression entering the SPIRR-CAD or MIND-IT intervention studies for depression [Citation7–8]. Of particular interest, the prevalence of current major depressive episode in our study was higher than those previously reported in similar studies and what has been reported in a review of studies among MI patients not taking type D personality into consideration (19.5%) [Citation8,Citation28]. Possible reasons for the higher prevalence rate may be that we only included patients 65 years of age or younger and conducted our assessments over a longer time period (18.4 months) since the last cardiac event compared to that of previous studies. The latter may be of importance since there is some evidence that depressed mood may increase over time in CHD patients [Citation29–30] and that type D is a risk factor for the development of depression after percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) [Citation31]. There is also some evidence of the contrary that the prevalence of depressive disorders is higher three months after MI than at one-year follow-up [Citation8]. Hence, the relationship between depression, type D personality and time since the cardiac event should be addressed in future studies.

We also found higher prevalence rates of anxiety disorders such as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia than previous studies. The prevalence rate of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is somewhat lower than that of other studies [Citation28], which may be due to a longer time period since the last cardiac event. Noteworthy is that the SPIRR-CAD study reported a higher rate of dysthymia than that in our study. One explanation may be that our study included unselected participants whereas the SPIRR-CAD study selected patients with depression who were motivated for participation in a treatment study. In our study, the rate of personality disorders was higher (38.2%) than that found in the only previous study assessing personality disorders [Citation7]. Avoidant and obsessive-compulsive disorders were the most frequent disorders in both studies. Interestingly, we also found a high rate of paranoid personality disorders, which may be a reflection of high levels of social inhibition, but future studies are needed to explore this relationship further.

This is the first study reporting whether patients with both type D personality and CHD receive effective treatment for their mood or anxiety disorders. Only 21% reported ongoing use of SSRIs and none received psychological treatment indicating that these patients are not screened and effectively treated for their psychiatric disorders. This is in line with a study that found that only 27% of those with major depressive disorder and CHD received any depression treatment [Citation27]. However, our result is consistent with the low prescription rate of antidepressants in patients with depression in Norway compared to other European countries [Citation32]

The results of our study clearly add to the evidence that Type D is a marker for more complex and serious disorders that need to be identified and effectively treated. Whether pharmacological or psychological treatment of mood and anxiety disorders would lead to a decrease in type D characteristics and potentially influencing clinical outcomes in these patients remains to be tested. There is some evidence that a stepwise psychotherapeutic approach to improve depressive symptoms is particularly beneficial for CHD patients with type D personality [Citation7].

Currently, there is no effective treatment for type D personality in CHD patients. It has been argued that proof of principle should be established before randomized controlled trials are conducted. Our assessment of metacognitions suggests that metacognitive therapy (MCT) [Citation12] targeting positive and negative metacognitive beliefs with subsequent reduction in rumination and negative affectivity may be beneficial for all patients with depressive symptoms and for those who score high on negative affectivity and hence may be effective for type D personality treatment. Surprisingly, we did not find any associations between metacognitions and social inhibition. This may suggest that other emotion-regulation strategies are more important for social inhibition than for negative affectivity and that these are indeed distinct traits [Citation33]. It has also been suggested that emotion-regulation in individuals who score high on SI deserves further investigation [Citation34]. In some studies, negative affectivity has been shown to be more strongly associated with prognosis and with the development of neo-atherosclerosis after PCI in CHD patients compared to social inhibition [Citation35]. Since metacognition has been reported as a potential underlying factor in personality trait [Citation36], identified in the support of the metacognitive model in cardiac patients [Citation37], and found as important components in the transdiagnostic metacognitive model, further testing of the metacognitive model for negative affectivity and social inhibition should be performed. Metacognitive therapy may be particularly suitable for these CHD patients as they tend to experience distress but are reluctant to discuss this openly [Citation38].

Limitations of our study include the lack of a comparison group and non-blinded assessment of psychiatric disorders according to type D status. The study patient group was restricted to patients 65 years of age or younger. On the other hand, younger patients have been found to have poorer prognosis associated with type D than those older than 70 years [Citation39]. In addition to establishing inter-rater reliability of the diagnostic assessments, all diagnoses were thoroughly discussed between two experienced research clinicians. The interviewer had extensive competency with assessments of psychiatric disorders in somatic patients with high to excellent reliability scores in previous studies [Citation40–41]. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design limits the assessment of the temporal relationship between type D personality and any disorders and we do not know if these patients developed their axis I disorders before or after their cardiac event. We do not know the appropriateness of anxiety and depression treatment including adherence, refusal, discontinuation or the extent to which patients in our study had undergone previous pharmacological/psychological interventions and thus may represent a treatment-resistant patient group. Furthermore, we do not know how well a population of 47 reflects the ‘true’ frequencies of comorbid psychiatric disorders in cardiovascular patients scoring high on social inhibition and negative affectivity. The very high Cronbach alpha values of some of the questionnaires indicate redundancy. Finally, a depressive state may affect the subjective score of trait measures such as the DS-14 and consequently future studies should examine the relationship between NA, SI, rumination and metacognitions in both patients with and without depression [Citation42].

Conclusion

This study found a high prevalence of mainly untreated mental disorders and significant correlations between rumination, metacognitions and negative affectivity but not social inhibition among chronic CHD patients. DS-14 may be a useful screening tool to identify CHD patients with complex disorders in need of mental health treatment. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to test the metacognitive model of type D personality in patients with CHD.

Author contributions

TD and CP developed the study concept. TD, JM and ES collected the data. TD, JM and TM contributed to the analysis and all authors contributed to the interpretation of data. TD drafted the manuscript. JM, ES, TM and CP critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank study patients for participating and study personnel for their invaluable contribution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kupper N, Denollet J. Personality as a risk factor in coronary heart disease: a review of current evidence. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20(11):104.

- Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the sixth joint task force of the european society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the european association for cardiovascular prevention & rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315–2381.

- Denollet J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and type D personality. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):89–97.

- Denollet J, Conraads VM. Type D personality and vulnerability to adverse outcomes in heart disease. Clev Clin J Med. 2011;78(Suppl 1):S13–S19.

- Bergvik S, Sørlie T, Wynn R, et al. Psychometric properties of the type D scale (DS-14) in norwegian cardiac patients. Scand J Psychol. 2010;51(4):334–340.

- Raykh OI, Sumin AN, Korok EV. The influence of personality type D on cardiovascular prognosis in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting: data from a 5-year-follow-up study. Int J Behav Med. 2022;29(1):46–56.

- Lambertus F, Herrmann-Lingen C, Fritzsche K, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders among depressed coronary patients with and without type D personality. Result of the multicenter SPIRR-CAD trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;50:69–75.

- Denollet J, de Jonge P, Kuyper A, et al. Depression and type D personality represent different forms of distress in the Myocardial INfarction and Depression – Intervention trial (MIND-IT). Psychol Med. 2009;39(5):749–756.

- Annagür BB, Demir K, Avci A, et al. Impact of a type D personality on clinical and psychometric properties in a sample of turkish patients with a first myocardial infarction. J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23(1):3–10.

- Wells A. Breaking the cybernetic code: understanding and treating the human metacognitive control system to enhance mental health. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2621.

- Messerli-Burgy N, Barth J, von Kanel R, et al. Maladaptive emotion regulation is related to distressed personalities in cardiac patients. Stress Health. 2012;28(4):347–352.

- Wells A. Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2009.

- Wells A, Matthews G. Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: the S-REF model. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(11–12):881–888.

- Normann N, van Emmerik AA, Morina N. The efficacy for metacognitive therapy on anxiety and depression: a metanalytic review. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(5):402–411.

- Normann N, Morina N. The efficacy of metacognitive therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2211.

- Munkhaugen J, Sverre E, Peersen K, et al. The role of medical and psychosocial factors for unfavourable coronary risk factor control. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2016;50(1):1–8.

- Sverre E, Peersen K, Husebye E, et al. Unfavourable risk factor control after coronary events in routine clinical practice. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):40.

- MacKenzie DM, Copp P, Shaw RJ, et al. Brief cognitive screening of the elderly: a comparison of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT) and Mental Status Questionnaire (MSQ). Psychol Med. 1996;26(2):427–430.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders–patient edition (SCID-IP. version 2.0. 4. 97 revision): biometrics research department. New York (NY): New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997.

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders, (SCID-II). Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997.

- Peersen K, Munkhaugen J, Gullestad L, et al. Reproducibility of an extensive self-report questionnaire used in secondary coronary prevention. Scand J Public Health. 2017;45(3):269–276.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(1):115–121.

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Metacognitive beliefs about rumination in recurrent major depression. Cogn Behav Pract. 2001;8(2):160–164.

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. Positive beliefs about depressive rumination: development and preliminary validation of a self-report scale. Behav Ther. 2001;32(1):13–26.

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. The negative beliefs about rumination scale in depression, rumination and metacognition: empirical tests of an information processing model Papageorgiou C [dissertation]. University of Manchester; 2004.

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. An empirical test of a clinical metacognitive model of rumination and depression. Cognit Ther Res. 2003;27(3):261–273.

- Kuhlmann SL, Arolt V, Haverkamp W, et al. Prevalence, 12-month prognosis, and clinical management need of depression in coronary heart disease patients: a prospective cohort study. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88(5):300–311.

- Kumar M, Nayak PK. Psychological sequelae of myocardial infarction. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:487–496.

- Konrad M, Jacob L, Rapp MA, et al. Depression risk in patients with coronary heart disease in Germany. World J Cardiol. 2016;8(9):547–552.

- Palacios JE, Khondoker M, Achilla E, et al. A single, one-off measure of depression and anxiety predicts future symptoms, higher healthcare costs, and lower quality of life in coronary heart disease patients: analysis from a multi-wave, primary care cohort study. PLOS One. 2016;11(7):e0158163.

- Al-Qezweny MN, Utens EM, Dulfer K, et al. The association between type D personality, and depression and anxiety ten years after PCI. Neth Heart J. 2016;24(9):538–543.

- Borge Hansen A, Baste V, Hetlevik O, et al. GPs’ drug treatment for depression by patients’ educational level: registry-based study. BJGP Open. 2021;5(2):BJGPO-2020-0122.

- Timmermans I, Versteeg H, Duijndam S, et al. Social inhibition and emotional distress in patients with coronary artery disease: the type D personality construct. J Health Psychol. 2019;14:1929–1944.

- Grande G, Glaesmer H, Roth M. The construct validity of social inhibition and the type-D taxonomy. J Health Psychol. 2010;15(7):1103–1112.

- Lee R, Yu H, Gao X, et al. The negative affectivity dimension of type D personality is associated with in-stent neoatherosclerosis in coronary patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: an optical coherence tomography study. J Psychosom Res. 2019;120(5):20–28.

- Nordahl H, Hjemdal O, Hagen R, et al. What lies beneath trait-anxiety? Testing the self-regulatory executive function model of vulnerability. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1–8.

- Anderson R, Capobianco L, Fisher P, et al. Testing relationships between metacognitive beliefs, anxiety and depression in cardiac and cancer patients: are they transdiagnostic? J Psychosom Res. 2019;124:109738.

- McPhillips R, Salmon P, Wells A, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation patients’ accounts of their emotional distress and psychological needs: a qualitative study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(11):e011117.

- Denollet J, Tekle FB, van der Voort PH, et al. Age-related differences in the effect of psychological distress on mortality: type D personality in younger versus older patients with cardiac arrhythmias. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:246035.

- Sagen U, Finset A, Moum T, et al. Early detection of patients at risk for anxiety, depression and apathy after stroke. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(1):80–85.

- Einvik G, Hrubos-Strøm H, Randby A, et al. Major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and cardiac biomarkers in subjects at high risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(5):378–384.

- Talaei-Khoei M, Mohamadi A, Fischerauer SF, et al. Type D personality in patients with upper-extremity musculoskeletal illness: internal consistency, structural validity and relationship to pain inference. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;50:38–44.