Abstract

Introduction

Suicide attempts by violent methods (VM) can leave the patient with physical and mental trauma affecting health-related quality of life (HRQOL). There is limited knowledge about the impact and HRQOL after a suicide attempt by VM.

Aims

To compare HRQOL in patients after a suicide attempt by VM, both to self-poisonings (SP) and the general population, and the association of hospital anxiety and depression to the HRQOL in the two groups.

Methods

Patients admitted to hospital after a suicide attempt were included in this prospective cohort-study from 2010 to 2015. For HRQOL, Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), and Hospital anxiety and depression scale scores (HADS-A and HADS-D) were assessed during study follow-up.

Results

The VM-group scored lower HRQOL for the physical dimensions at 3 months (p<.05), compared to the SP group, and only role limitation physical at 12 months (p<.05). Both groups scored lower HRQOL than the general population (p < .05).

At baseline, the VM group scored lower for HADS-A than the SP group (p < .05). Both groups had lower HADS scores one year after (p < .05). In multiple regression analyses, the HADS scores were associated with HRQOL in the VM-group (p < .05). SP group HADS scores were negatively associated with general health, vitality, social functioning, and mental health (p < .05).

Conclusion

Both groups scored lower for HRQOL than the general population, and the VM group had worse score than the SP group in physical dimensions. Both groups had less symptoms of anxiety and depression over time, but it`s association to HRQOL was strong.

Keywords:

Background

Suicide attempts is a major public health concern worldwide, with more than 700,000 deaths by suicide every year [Citation1]. It is estimated that about 10 to 15% of suicide attempts eventually die by suicide, and a previous suicide attempt is the strongest known risk factor for later suicide [Citation2]. The risk factors for suicide attempts and suicide are otherwise similar, with a higher suicide risk for males, for people with mental disorders, and for people with a family history of suicide [Citation3], and for those using a more lethal method [Citation4].

Suicide attempters using a violent method (VM) are found to be more impaired in the decision-making process and have a higher risk of future suicide [Citation5,Citation6] than those using non-violent methods (mainly self-poisoning (SP)) [Citation7]. The choice of method inflicts on the immediate risk of dying, but also on the risk of sequelae for survivors [Citation8]. Furthermore, choice of method is a predictor for increased mortality and death by suicide in the long term [Citation8]. There are also gender differences in the choice of method. Males, as a group, tend to favor more VM, whereas females predominately use SP [Citation8–10]. Young people more often use VM than the elder [Citation9]. Suicide deaths among the elderly are now on the rise [Citation11], with a higher intent and less impulsive suicide attempts, more frequently using SP as a method [Citation12].

An American study found that about 2/3 of suicide attempts admitted to the Emergency Department were by SP and about 1/4 were by VM [Citation13]. In Norway, approximately 2/3 of deaths from suicide are by VM [Citation14]. Furthermore, no systematic data for methods used in suicide attempts are available in Norway, but suicide attempts admitted to the hospital by VM are notably fewer than those admitted by SP [Citation15, Citation16].

Patients admitted to the hospital after a suicide attempt may survive the initial attempt, but this may still have a lifelong impact on their functioning [Citation2,Citation17]. According to the choice of method and the outcome of the hospitalization, the VM group was more injured and needed more intensive care than the SP group [Citation18].

The multi-dimensional concept of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) covers physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning dimensions, measured using standardized scales [Citation19, Citation20]. Little is known about HRQOL among patients admitted for suicide attempts by VM compared to SP. Though HRQOL in patients admitted for suicide attempts compared to the general population is assumed to be lower due to the possible physical sequelae after the suicide attempt, this aspect is less studied than risk factors for later suicide [Citation21]. There is a known association between low HRQOL and suicidal thoughts or attempts [Citation22], and the HRQOL of suicide attempters was significantly lower than the HRQOL of matched healthy controls in one study [Citation23]. More specifically, lower HRQOL in the physical dimensions was found in survivors after suicide attempts by jumping compared to the general population [Citation24, Citation25]. More bodily injury and longer rehabilitation time among VM patients than SP patients may also contribute to a lower quality of life. Knowledge of HRQOL following suicide attempts by VM may allow us to target interventions early in treatment and rehabilitation.

Anxiety and depression disorders are associated with suicide attempts [Citation22] and with impairment of HRQOL [Citation26]. Patients with anxiety and depression more often report lower quality of life and more lifetime suicide attempts [Citation26]. Therefore, lower HRQOL among patients admitted for suicide attempts may be related to their mental health, and not only to the episode leading to hospitalization. Comparison of VM and SP is rare. No previous studies have been found that compare the quality of life between VM and SP. The findings in this study may therefore contribute to filling the knowledge gaps regarding HRQOL for patients attempting suicide.

Aims

We wanted to compare HRQOL in patients after a suicide attempt by VM to patients discharged from the hospital after SP after three and twelve months and compare results for HRQOL to the general population using the Norwegian living condition study. Furthermore, we wanted to compare the two patient groups’ hospital anxiety and depression scores, and how these anxiety and depression scores were associated with the reported HRQOL among patients admitted for suicide attempts.

Methods

Design and setting

This prospective multicenter cohort study was designed to examine longitudinal outcomes of patients admitted to the hospital after suicide attempts by VM compared to SP. The study was performed at Oslo University Hospital (OUH), Ullevaal, a trauma referral Centre for Eastern and Southern Norway serving approximately 2.7 million people. Patients from other regional hospitals were also included, although the majority was treated at Oslo University Hospital, as described previously [Citation18].

Characteristics of participants

All patients between 18 and 80 years admitted to a somatic hospital after a suicide attempt by VM were eligible for inclusion. Due to the written questionnaires, patients who did not understand oral and written Norwegian, not having the capability to consent, sustained a severe head injury, were mentally disabled and/or psychotic, or did not have a fixed address were excluded. We defined VM as all methods inflicting harm to the patients requiring hospital treatment, consisting of cutting, jumping from heights, hanging, firearms, drowning and others (intentionally car accident, fire or jumping in front of train), excluding self-poisoning [Citation27]. Self-poisoning was defined as self-inflicted poisoning in a suicide attempt [Citation27, Citation28]. Each included patient was paired with a control admitted after a suicide attempt with SP within three months, matched for gender and age ± 5 years. The original cohort included 161 patients between December 2010 and April 2015; 80 patients used VM (63% males, mean age males 43.1, females 37.8 yrs., where 22% had injuries related to the head or neck, and 35% had injuries related to the thorax, spinal canal, or the back), and 81 patients used SP (47% males, mean age: males 45, females 39 yrs.).

Data collection and measurements

The patients completed the initial questionnaire during the hospital stay for baseline data. Follow-up questionnaires regarding life conditions and HRQOL, were sent by mail to the patients at 3 and 12 months after discharge. We wanted to use SF 36 to measure HRQOL, but not at baseline. The other baseline data was collected shortly after the initial attempt (days). The suicide attempt was considered an acute crisis, and we did not measure the HRQOL right during the crisis. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed, but questions regarding job satisfaction and social functioning did not seem relevant during the hospital stay. However, doing this after a shorter period would have been possible. We chose to do it after 3 and 12 months, in a more stable situation, to assess the HRQOL.

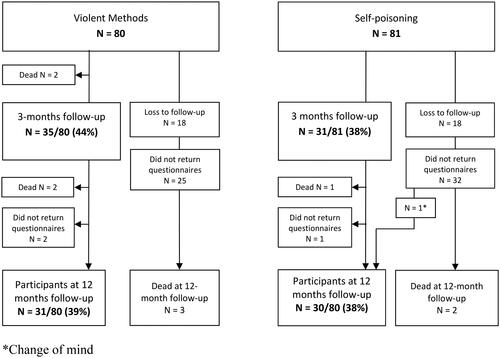

During the follow-up period (3–12 months), two patients died in the VM group and one of the patients in the SP group which gave a total death toll of 7 and 3, respectively (). A total of 36 patients (18 VM and 18 SP) were excluded, as they could not be reached by mail or phone ().

In order to assess HRQOL, the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) was used to assess the patient’s physical and emotional health at three- and twelve-month follow-ups [Citation19]. The SF-36 is a patient-reported survey for general health status containing a 36-item questionnaire covering eight dimensions; physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health [Citation29, Citation30]. High scores (range 0–100) indicate a higher level of functioning or freedom from pain [Citation19] and are associated with a better quality of life and state of health [Citation25]. The Norwegian translation of SF-36 has been well validated [Citation31].

In addition, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure the symptom burden of anxiety and depression [Citation20, Citation32]. Anxiety and depression are important factors that could inflict HRQOL and were assessed separately. Although not measuring HRQOL, the HADS scale is recommended to support a clinical practice when SF-36 is used for quality-of-life assessment [Citation33, Citation34]. The HADS questionnaire consists of 14 questions, holding seven for HADS-A and seven for HADS-D, each item scores from 0 to 3 [Citation32], obtained at baseline, three- and twelve-month follow-up. Scores ≥ 8 indicate symptoms of clinical importance. Each patient was allocated to one of three categories for anxiety and depression, based on individual final scores: 0–7 normal, 8–10 mild and 11+ moderate to severe [Citation35]. In order to validate the findings in the HADS scores, a drop-out analysis was carried out for responders versus non-responders at follow-up. To achieve statistical power, we intended to include 100 patients in the VM group and twice as many in the SP group. Due to the extended use of time because of fewer patients eligible, we terminated the study inclusion after 4.5 years. However, we consider the matching with the SP patients to be sufficient for the primary dependent variables.

The Norwegian living conditions survey

SF-36 scores for the participants were compared to the general population in Norway using SF-36 data from a longitudinal population health study from 2015 (n = 2118), known as The Norwegian living conditions study [Citation36]. The validated Norwegian living conditions study is representative of earlier and larger population studies such as HUNT in Norway [Citation36].

Statistical methods

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 26; IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses. Data on categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented with a mean score, 95% confidence interval, and standard deviation. There were no missing data in the SF-36 and HADS data. The analyses were performed only for those who responded at all-time points. Using the SPSS analysis program, we checked the descriptive statistics and ran a skewness test to check for normal distribution (or skewed). Our variables turned out to be approximately normal.

An independent sample Student’s t-test was used to compare the means between two groups on continuous variables, and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed for skewed distributed data. Using results from OpenEpi, Version 3, an open-source calculator, a t-test was performed by using sample size, mean and standard deviation and setting a two-sided confidence interval to 95%, we present scores for SF 36 following the general population.

A paired sample t-test was used when comparing mean scores within groups at two time points.

A General Linear Model, using multivariate tests, was used to measure the effect over time for HADS within the groups and measure the effect of time as a factor for change between the groups. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The internal consistency of the mean was tested in the SF-36 form and for both HADS-A and HADS-D scales, using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, which exceeded 0.8 at all measurement points. If the items in a test are more correlated, the score of Cronbach’s alpha is higher, expressed as a number between zero and one. The score should be at least 0.70 for the variable to be satisfactory [Citation37].

A multiple linear regression analysis was performed to investigate whether HADS anxiety or HADS depression, adjusted for demographic variables, was associated with HRQOL domains within groups of methods used. The contribution of each individual parameter was studied in an univariate linear regression analysis, and the results from the analyses are reported as regression coefficients (β)+ with 95% Confidence Interval, p values, and explained variances (adjusted R2).

Ethics

The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and the Regional Ethics Committee and the Data Protection Officer at Oslo University Hospital approved the study (REK:2010/1487). The patients were informed and signed a written consent during the hospital stay. No patients withdrew their consent during the study period, but several participants were lost for follow-up because of unknown new addresses and telephone numbers ().

Results

At the three-month follow-up, the VM group scored significantly lower than the SP group on physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, bodily pain, and role limitation due to emotional problems (). At the 12-month follow-up, the VM group scored significantly lower than the SP group only on role limitation due to physical problems. Comparing scores from three to twelve months, the VM group improved significantly over time regarding physical functioning and mental health (). In both groups, all participants responded to all SF-36 dimensions.

Table 1. Mean SF-36 scale scores for the VM and SF group at 3- and 12-month follow-up.

Compared to the Norwegian living condition study, a significantly lower score was measured for HRQOL in all eight dimensions in SF-36 for both males and females in the VM group at twelve-month follow-ups (). For males in the SP group, a significantly lower score was measured for HRQOL in all eight dimensions, except bodily pain, and a significantly lower score was measured for females in the SP group scored for all dimensions, except physical functioning and bodily pain at twelve-month follow-ups.

Table 2. SF-36 Scale Scores after suicide attempt by VM or SF according to gender and time to follow-up, and compared to the Norwegian living condition study.

In , both groups had high scores for anxiety and depression. At baseline, there were significantly lower HADS-A mean scores in the VM group compared to the SP group (mean 9.3 vs. 11.7, respectively, p < .05). No differences were seen for HADS-A and HADS-D between the groups at either three- or twelve-month follow-ups (). Within the VM group, the HADS-A mean score did not change significantly between baseline, three-month, and twelve-month (9.3, 8.9, and 8.3, respectively, p = .05), but for the SP group, the HADS-A mean score was significantly lower at the twelve-month point compared to baseline (11.7, 9.0 and 8.0, respectively, p < .05) ().

Table 3. Hospital anxiety and depression scores at baseline, 3 months and 12 months for patients attempting suicide using violent methods compared to self-poisoning.

There were no significant differences in the HADS-D mean scores between the groups. The HADS-D mean score was significantly lower at twelve-month than baseline for both the VM and SP groups (both with p < .05). There were no significant differences in mean scores for HADS-A (VM group 10.3 vs. 9.3 and SP group 11.5 vs. 11.7) and HADS-D (VM group 8.7 vs. 8.6 and SP group 9.8 vs. 9.4) between patients lost to follow-up and patients responding to all variables at all three time-points.

In , we adjusted for demographic variables. As such, the independent variables, anxiety- and depression-scores, were associated significantly with all the VM HRQOL scores measured at the twelve-month follow-up. When controlled for other variables, increased HADS-A and HADS-D scores explained a lower HRQOL.

Table 4. Multivariable linear regression analyses of SF-36 at 12 months follow-up and associations to hospital anxiety and depression score and adjusted for demographic variables according to method used in suicide attempt.

For the SP group, the anxiety and depression scores were associated with the SF-36 dimensions; social functioning and mental health (both with p= < .001), vitality (p= .001), and general health (p= < .05) (). Note the reliability in the model, as the adjusted R–square was high for the VM group. The SP groups adjusted R-square was high (> 0.6) for those SF-36 dimensions where the association was significant.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that patients attempting suicide with VM had lower scores of HRQOL than the SP group at three-month for four of the eight dimensions studied (physical functioning, role limitation physical, bodily pain, role limitation emotional). As such, the VM group improved during the study period, especially regarding physical functioning and mental health, whereas the SP group reported no significant improvement. All patients experienced symptoms of anxiety and depression, associated with lower HRQOL.

The physical consequences of the violent methods used were the main difference between the groups at three- and twelve-month follow-up. Patients attempting suicide by VM are more vulnerable, as they may suffer physical sequelae after discharge because of injuries to the skeleton, neck, internal organs, or spinal cord [Citation18, Citation27], resulting in an even more significant impact on the quality of life or Health-related Quality of Life (HRQOL). Mutilation because of shotgun wounds to the head, knife wounds in the abdomen or neck, or spinal cord injuries due to hanging will require long rehabilitation and may result in life-long sequelae for some. We did not investigate how common brain injury and back pain was among VM suicide survivors in our study. However, others have shown that among patients surviving suicide attempts by VM, attempts by hanging are at high mortality risk because of head injuries and anoxic brain injuries [Citation38], and patients surviving from a firearm injury differed between assault and self-inflicted [Citation39]. Among patients who attempted suicide by jumping, they found brain injury to cause death and mostly fractures in the skeleton for survivors [Citation40].

Lower HRQOL has a substantial impact on patients attempting suicide by VM. This is in accordance with the fact that physical health is crucial for the experience of a good quality of life [Citation41–43]. However, in our previous study comparing these two groups [Citation44], we found that the VM group had a higher suicidal intent compared to the SP group, which may be reflected in their choice of method on a group level.

Previous studies with SF-36 and HADS have mostly focused on different disease categories separately (Intensive care patients, cardiac surgery, cancer patients, neurological patients, or medical patients), with findings of, in contrast to the present study, improvement in HRQOL score over time [Citation34, Citation42, Citation45]. When using SF-36 and HADS for analyses in our study, slight improvements were seen for anxiety and depression one year after the attempt in both groups, while HRQOL scores remained poor.

Different methodologies and assessment time between studies have made comparing disease categories difficult. Though focusing on suicide ideation, Goldney et al. found that adolescents with suicidal thoughts reported significantly poorer HRQOL than people without suicidal thoughts [Citation46], and poorer HRQOL was associated with higher odds of suicide ideation onset [Citation47]. The VM and SP groups scored low for HRQOL in the present study. Though, there was found high suicide ideation over time in patients attempting suicide by VM [Citation44].

Farabaugh et al. [Citation48] found that college students with poorer HRQOL were more likely to endorse suicidal ideation and that poorer HRQOL was still a significant predictor of suicidal ideation. Patients with higher suicide ideation and suicide intent score higher for anxiety and depression [Citation44], and according to the results from the present study, high anxiety and depression scores provide poorer quality of life.

Both patient groups had lower scores for HRQOL than the general population one year after the suicide attempt. According to methods used in suicide attempts, only one Swedish prospective study compared suicide attempts by jumping to the average population using SF-36. In all SF-36 domains, the patients scored lower than the Swedish norm group [Citation25]. This is in concordance with the present study, where all dimension scores for both VM and SP groups were lower than in the Norwegian population. In the absence of a satisfactory HRQOL, it is therefore important to provide these patients with a good follow-up.

Both groups’ scores were high for anxiety and depression over time, and a high score for anxiety and depression was associated with lower HRQOL 12 months after hospitalization. In contrast to the SP group, the VM group did not score significantly better regarding anxiety one year after the initial attempt. However, both groups scored better for depression. Previous studies for cancer patients found anxiety to be associated with the SF-36 summary scales, especially with the mental dimensions (49%). In comparison, depression was also associated mostly with the mental dimensions (45%) in the HRQOL [Citation49]. According to our findings, anxiety and depression are associated with both the physical and mental dimensions in the SF-36 summary scales for the VM group and more with the mental dimensions for the SP group. In a linear regression analysis, Soberg et al. revealed that severe brain injury influenced HRQOL twelve months after the injury [Citation50], and others found that back pain correlated to HADS [Citation51].

We could not find any studies comparing how anxiety and depression affect the different method choices in suicide attempts. Differences within the groups, related to gender and more psychosis for the VM group [Citation8], and more depression and anxiety in the SP group [Citation18], may affect the results. Since the VM group had more physical injuries and, therefore, more ailments over time, we may assume that this could affect the HRQOL more than the SP group regarding depression and distress symptoms, as measured by HADS. In our cohort, when controlling for demographic variables in a regression analysis, the HADS-A and HADS-D were associated more with HRQOL for the VM group than the SP group according to physical dimensions. Since scores and outcomes for the mental dimensions were more similar over time between the groups, we also noted a similar association between anxiety and depression and the mental dimensions, and a strong association was found for both groups one year after the suicide attempt.

Suicide attempts by VM are a rare occurrence. Our findings regarding this group may be helpful for other major hospitals treating similar patients, especially in Scandinavian countries or other similar countries as well [Citation52].

Strengths and limitations

An essential strength of this study is the novelty of the research question, as no previous prospective cohort studies comparing HRQOL between VM and SP were found. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examines the quality of life and compare methods used in suicide attempts leading to hospitalization, and the first to our knowledge using both the SF36 and the HADS when comparing the two groups. When using postal surveys, the patients do not have the possibility to ask questions concerning the questionnaires. To avoid this problem, the patients were contacted by phone and asked if they had questions regarding the study and the forms. We excluded patients who did not understand Norwegian, thus removing the possibility of further misunderstandings because of language problems.

The exclusion above is also a limitation as we may lose vital information from groups having difficulties in their new country where they do not understand the language. During the follow-up period, a considerable proportion of these vulnerable patients were lost. Study limitations also included a modest sample size, and larger data sets could allow the use of more sophisticated statistical techniques to assess answers towards HRQOL among patients attempting suicide. Among the 161 patients measured at baseline, only 61 (38%) remained at twelve months. Considering this population´s vulnerability, a sample size relapse was expected, as was also the case when we earlier studied self-poisonings [Citation53]. Another weakness relates to the use of self-reported measures of HRQOL, which may be influenced by the patient’s personal mood that very day. There were a higher HADS score at baseline and a lower score for SF-36, especially for the VM group for those who were lost to follow-up. Accordingly, the data analyses carry risks of bias, and our findings may therefore have been even worse if all patients had completed the study.

Clinical implication

Patients attempting suicide by VM had physical consequences, both reversible and not reversible, and scored lower for the physical dimensions in HRQOL. More intensive follow-up seems therefore required. It is crucial to adopt a treatment for both mental illness and physical ailments combined with good pain relief in patients admitted to hospital after a suicide attempt by VM. Patients with SP also had high scores for anxiety and depression and low for HRQOL after the suicide attempt. One year after the suicide attempt, the symptoms, except for the physical dimensions, were most pronounced in the VM group. The low HRQOL may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts. Therefore, HRQOL must be followed closely after the suicidal attempt.

Conclusion

Patients with physical sequelae after the suicide attempt naturally have a worse score on the physical dimensions of quality of life, but there were more similarities than differences in the experience of quality of life measured between the groups. Both patients using VM and SP had significant psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression, one year after the suicide attempt, and compared to the general population, these two groups had a much poorer quality of life. In assessing suicide risk, measuring the quality of life is also essential, as these dimensions are significantly reduced.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the collaborators from other hospitals: Bente Rabba, Innlandet Hospital Trust; Anny Mortensen, University Hospital of Northern Norway (UNN); Trond Jørgensen, Akershus University Hospital (AHUS); Jørn Bøtker, Haukeland University Hospital (HUS); and Andrea Chioqueta, Stavanger University Hospital (SUS). Furthermore, we would like to thank all employees at the Department of Acute Medicine and at the Trauma Centre at Oslo University Hospital. In addition, we thank Catrine Brunborg at the Oslo Centre for Biostatistics and Epidemiology (OCBE) for valuable help in statistical calculations.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Data availability statement

Data relating to this article can be made available by agreement with the author. Data is linked to the hospital’s server and is subject to sensitive data.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Surveys., W.H.O.s.W.M.H. Mental health and substance use. Suicide data. who.int, 2019.

- Suominen K, Isometsä E, Suokas J, et al. Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):562–563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.562.

- Hawton K, Casañas I Comabella C, Haw C, et al. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1–3):17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004.

- Isometsa E. Suicidal behaviour in mood disorders–who, when, and why? Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(3):120–130. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900303.

- Bergen H, Hawton K, Waters K, et al. How do methods of non-fatal self-harm relate to eventual suicide? J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.036.

- Probert-Lindström S, Öjehagen A, Ambrus L, et al. Excess mortality by suicide in high-risk subgroups of suicide attempters: a prospective study of standardised mortality rates in suicide attempters examined at a medical emergency inpatient unit. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e054898. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054898.

- Gorlyn M, Keilp JG, Oquendo MA, et al. Iowa gambling task performance in currently depressed suicide attempters. Psychiatry Res. 2013;207(3):150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.030.

- Runeson B, Tidemalm D, Dahlin M, et al. Method of attempted suicide as predictor of subsequent successful suicide: national long term cohort study. BMJ. 2010;341(1):c3222–c3222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3222.

- Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, et al. Age differences in behaviors leading to completed suicide. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;6(2):122–126. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199805000-00005.

- Nordentoft M, Branner J. Gender differences in suicidal intent and choice of method among suicide attempters. Crisis. 2008;29(4):209–212. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.29.4.209.

- Wiktorsson S, Runeson B, Skoog I, et al. Attempted suicide in the elderly: characteristics of suicide attempters 70 years and older and a general population comparison group. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):57–67. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bd1c13.

- Wiktorsson S, Strömsten L, Renberg ES, et al. Clinical characteristics in older, middle-aged and young adults who present with suicide attempts at psychiatric emergency departments: a multisite study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;30(3):342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.08.001.

- Canner JK, Giuliano K, Selvarajah S, et al. Emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self harm in the USA: 2006-2013. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(1):94–102. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000871.

- FHI. Statistics Norway FHI. 2021.

- Bjornaas MA, Jacobsen D, Haldorsen T, et al. Mortality and causes of death after hospital-treated self-poisoning in Oslo: a 20-year follow-up. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47(2):116–123. doi: 10.1080/15563650701771981.

- Heyerdahl F, Bjornaas MA, Dahl R, et al. Repetition of acute poisoning in Oslo: 1-year prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(1):73–79. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048322.

- O'Connor RC, Smyth R, Ferguson E, et al. Psychological processes and repeat suicidal behavior: a four-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(6):1137–1143. doi: 10.1037/a0033751.

- Persett PS, Grimholt TK, Ekeberg O, et al. Patients admitted to hospital after suicide attempt with violent methods compared to patients with deliberate self-poisoning – a study of background variables, somatic and psychiatric health and suicidal behavior. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1602-5.

- Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002.

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3.

- Qin P. Suicide risk in relation to level of urbanicity–a population-based linkage study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(4):846–852. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi085.

- Balazs J, Miklosi M, Halasz J, et al. Suicidal risk, psychopathology, and quality of life in a clinical population of adolescents. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00017.

- Kumar PN, George B. Life events, social support, coping strategies, and quality of life in attempted suicide: a case-control study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(1):46–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105504.

- Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Ware JE.Jr., The swedish SF-36 health survey–I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1349–1358. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00125-q.

- Borg T, Holstad M, Larsson S. Quality of life in patients operated for pelvic fractures caused by suicide attempt by jumping. Scand J Surg. 2010;99(3):180–186. doi: 10.1177/145749691009900314.

- Das-Munshi J, Goldberg D, Bebbington PE, et al. Public health significance of mixed anxiety and depression: beyond current classification. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(3):171–177. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036707.

- Stenbacka M, Jokinen J. Violent and non-violent methods of attempted and completed suicide in swedish young men: the role of early risk factors. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1):196. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0570-2.

- Giner L, Jaussent I, Olié E, et al. Violent and serious suicide attempters: one step closer to suicide? J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(3):e191-7–e197. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08524.

- Myhren H, Tøien K, Ekeberg O, et al. Patients’ memory and psychological distress after ICU stay compared with expectations of the relatives. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(12):2078–2086. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1614-1.

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr., Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006.

- Loge JH, Kaasa S. Short form 36 (SF-36) health survey: normative data from the general norwegian population. Scand J Soc Med. 1998;26(4):250–258. doi: 10.1177/14034948980260040401.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

- Kancir CB. A comparison of short form 36 and hospital anxiety and depression scale based on patients 1 month after discharge from the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2010;14(Suppl 1):P440. doi: 10.1186/cc8672.

- Tøien K, Bredal IS, Skogstad L, et al. Health related quality of life in trauma patients. Data from a one-year follow up study compared with the general population. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2011;19(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-22.

- Stern AF. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(5):393–394. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu024.

- Jacobsen EL, Bye A, Aass N, et al. Norwegian reference values for the short-form health survey 36: development over time. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1201–1212. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1684-4.

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the SF-36 in eleven countries: results from the IQOLA project. International quality of life assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00106-1.

- Nichols SD, McCarthy MC, Ekeh AP, et al. Outcome of cervical near-hanging injuries. J Trauma. 2009;66(1):174–178. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817f2c57.

- Bertisch H, Krellman JW, Bergquist TF, et al. Characteristics of firearm brain injury survivors in the traumatic brain injury model systems (TBIMS) national database: a comparison of assault and self-inflicted injury survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(11):2288–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2017.04.006.

- Giordano V, Santos FSE, Prata C, et al. Patterns and management of musculoskeletal injuries in attempted suicide by jumping from a height: a single, regional level I trauma center experience. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48(2):915–920. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01499-7.

- Erlangsen A, Banks E, Joshy G, et al. Measures of mental, physical, and social wellbeing and their association with death by suicide and self-harm in a cohort of 266,324 persons aged 45 years and over. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(2):295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01929-2.

- Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Health-related quality of life and return to work after critical illness in general intensive care unit patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1554–1561. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e2c8b1.

- Cuthbertson BH, Scott J, Strachan M, et al. Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(4):332–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04109.x.

- Persett PS, Ekeberg Ø, Jacobsen D, et al. Higher suicide intent in patients attempting suicide with violent methods versus self-poisoning. Crisis. 2022;43(3):220–227. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000773.

- Ulvik B, Bjelland I, Hanestad BR, et al. Comparison of the short form 36 and the hospital anxiety and depression scale measuring emotional distress in patients admitted for elective coronary angiography. Heart Lung. 2008;37(4):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.08.001.

- Goldney RD, Fisher LJ, Wilson DH, et al. Suicidal ideation and health-related quality of life in the community. Med J Aust. 2001;175(10):546–549. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143717.x.

- Fairweather-Schmidt AK, Batterham PJ, Butterworth P, et al. The impact of suicidality on health-related quality of life: a latent growth curve analysis of community-based data. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.067.

- Farabaugh A, Bitran S, Nyer M, et al. Depression and suicidal ideation in college students. Psychopathology. 2012;45(4):228–234. doi: 10.1159/000331598.

- Fossa SD, Dahl AA. Short form 36 and hospital anxiety and depression scale. A comparison based on patients with testicular cancer. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(2):79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00308-7.

- Soberg HL, Røe C, Anke A, et al. Health-related quality of life 12 months after severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective nationwide cohort study. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(8):785–791. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1158.

- Weßollek K, Kowark A, Czaplik M, et al. Pain drawing as a screening tool for anxiety, depression and reduced health-related quality of life in back pain patients: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258329.

- Todorov L, Vulser H, Pirracchio R, et al. Suicide attempts by jumping and length of stay in general hospital: a retrospective study of 225 patients. J Psychosom Res. 2019;119:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.02.001.

- Grimholt TK, Jacobsen D, Haavet OR, et al. Effect of systematic follow-up by general practitioners after deliberate Self-Poisoning: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143934.