Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to investigate if temperament and experience of childhood trauma differed between young psychiatric patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), bipolar disorder (BD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Methods

Diagnoses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Axis I and Axis II. Temperament was assessed by the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) and childhood trauma by the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report-Short Form (ETI-SR-SF). Temperament and childhood trauma were compared between the BPD group (n = 19) and the non-BPD group (BD/ADHD) (n = 95). Interactions between trauma and temperament were evaluated using a logistic regression model with a BPD diagnosis as outcome variable.

Results

Participants in the BPD group showed higher novelty seeking (NS) and harm avoidance (HA). Traumatic experiences in childhood were common but the BPD group differed very little from the others in this regard. The interaction between temperament and trauma had low explanatory power for a BPD diagnosis in this sample.

Conclusion

Temperament might be useful to distinguish BPD when symptoms of impulsivity and affective instability are evaluated in psychiatric patients. The results from the interaction analysis support the multifactorial background to BPD.

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by affective dysregulation, interpersonal problems, impulsivity, lower quality of life and with high levels of psychosocial impairment and increased risk of suicide [Citation1,Citation2]. The interaction between biological temperament and environmental factors is included in several models of BPD development, such as the biopsychosocial developmental model for BPD, the multifactorial model and Cloninger’s psychobiological model for the development of personality [Citation3–5]. A heritability of 46% is estimated for BPD [Citation6]. Experience of childhood maltreatment is common in patients with BPD/BPD symptoms [Citation7,Citation8]. Both prospective and cross-sectional studies indicate that childhood abuse is an important factor for BPD development [Citation9,Citation10]. A recent meta-analysis indicated that individuals with BPD were more likely to report adverse events in childhood than patients with other psychiatric disorders [Citation11]. BPD patients have been shown to report more emotional and sexual abuse compared to individuals with adult ADHD and BD [Citation12].

Cloninger et al.’s psychobiological model incorporates temperament as the heritable determinant [Citation5]. The model assumes that the phenotypic structure of personality develops as a result of interactions between temperament and environmental influences. Cloninger’s model includes four dimensions of temperament: novelty seeking (NS), harm avoidance (HA), reward dependence (RD), and persistence (PS). High values of HA and NS have been associated with BPD [Citation13,Citation14]. These biological temperaments, HA and NS, together with experience of childhood trauma are considered to be one developmental pathway to BPD. A recent review indicates that the effect on early development of BPD is caused by the interaction between risk factors and not their separate effects, for example, the interaction between childhood maltreatment and temperamental traits [Citation15]. To our knowledge, there are no studies that have explored how specific to BPD the interaction between temperament and childhood trauma is, especially when compared with other psychiatric diagnoses with similar emotional instability and impulsivity, such as bipolar disorder (BD), and or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Therefore, analyzing differences in temperamental traits and childhood maltreatment between BPD and ADHD/BD and to explore a theoretical model of interaction between these risk factors would add additional light on the developmental antecedents of BPD.

The aim of this study was to investigate the associations between childhood trauma, Cloninger’s four dimensions of temperament, and a BPD diagnosis in psychiatric patients with BPD, BD, and or ADHD. Our hypothesis was that individuals with BPD, compared to individuals with BD and/or ADHD, would have higher levels of HA and/or NS in combination with having experienced more childhood trauma.

Materials and methods

Participants

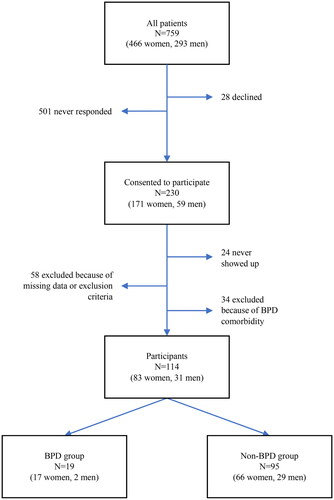

Patients from an outpatient psychiatric clinic for young adults (18–25 years, N = 759) in Uppsala, Sweden, diagnosed with BPD, ADHD, or BD, between 1 May 2005 and 31 October 2010, were identified in the administrative patient register and received a postal invitation to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were severe psychotic or manic symptoms at the time of the interview. One patient was excluded because of current mania. Thirty-four participants had a BPD diagnosis with comorbid ADHD and/or BD, and they were also excluded from the analyses. For description of the recruitment process, see . A total of 114 patients were finally included in the study (BPD: n = 19, non-BPD: n = 95).

Dropout analysis

Comparing the dropouts (n = 645) with those participating (n = 114) revealed that there were more women among the participants, 72.8% vs. 59.4% (χ2 = 7.369, p < .01), fewer individuals with an ADHD diagnosis, 28.1% vs. 45.7% (χ2 = 7.056, p < .01), and more with a BD diagnosis, 43.9% vs. 31.2% (χ2 = 12.330, p < .01).

Procedure

The study design was cross-sectional. The participants were interviewed by three psychiatrists/residents in psychiatry (MR, IK and NH) beginning with a basic interview about anamnestic, social, and demographic data that was performed, using a checklist. All diagnoses were based on structured diagnostic interviews performed either before or at the study entrance. All interviewers were previously trained and quality-assured interviewers, and in 99% of all cases it was MR, IK, or NH who performed the interviews. Inter-rater reliability for MR, IK and NH for this study was assessed based on randomly selected audiotaped interviews performed with the participants. The results are presented below, under each instrument. For each interview, there could be three protocols, one for each rater. Since the number of protocols varied, both the number of interviews and the number of protocols are presented. Lastly, patients filled out study questionnaires about temperament and childhood trauma.

The analyses were done in two steps. First, the effects of childhood trauma and temperament on BPD were analyzed, independently of each other, in order to explore the individual effects of the two factors. In the second step, both childhood trauma and temperament were included in a theory testing model, in an explorative attempt to investigate if they could distinguish the BPD group from the non-BPD group.

Assessments

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-Axis I Clinical Version (SCID-I-CV)

The SCID-I-CV [Citation16] is a semi-structured clinical interview that assesses diagnoses in accordance with the Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Mean prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) calculated for the three interviewers (MR, IK, NH) was 0.95 (range 0.91–0.97) based on six SCID-I interviews (13 protocols).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-Axis II (SCID-II)

The SCID-II is a semi-structured diagnostic interview for assessment of personality disorders in accordance with DSM-IV [Citation17]. If a patient reported items above the cut-off for any other personality disorder in the SCID-II personality questionnaire, that disorder was evaluated through interviewing, assessing all criteria for the disorder together with the general personality disorder criteria. According to the DSM-IV, a BPD diagnosis requires the fulfillment of five out of nine criteria. These criteria include fear of abandonment (criterion one, SCID question 90), dysfunctional patterns of interpersonal relationships (criterion two, SCID question 91), identity disturbance (criterion three, SCID questions 92–95), impulsivity (criterion four, SCID question 96), recurrent suicidal behavior (criterion five, SCID questions 97–98), affective instability (criterion six, SCID question 99), chronic feelings of emptiness (criterion seven, SCID question 100), intensive anger (criterion eight, SCID questions 101–103), and dissociative symptoms (criterion nine, SCID question 104).

The inter-rater reliability for the three interviewers (MR, IK, NH) measured with PABAK was 0.85 (range 0.79–0.88) based on nine SCID-II interviews (23 protocols).

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS, Supplement for ADHD)

The K-SADS is a semi-structured interview for children between the ages of six and eighteen years, measuring child psychiatric disorders in accordance with DSM-IV [Citation18]. Because of the lack of validated interviews in Swedish translation for assessing ADHD in adults, the K-SADS supplement for ADHD was chosen for these young adults. We composed a list of DSM-IV criteria for ADHD that corresponded to the questions included in the K-SADS supplement for ADHD. All criteria were assessed based on the participants’ information. However, no parents took part. The participants were asked to consider whether symptoms were present before the age of seven. The inter-rater reliability for the three interviewers (MR, IK, NH) measured with PABAK was 0.72 (range 0.64–0.81) based on four interviews (11 protocols).

Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI)

The TCI is a self-report questionnaire that comprises 238 true/false items, based on Cloninger’s psychobiological model and measures four temperament scales – NS, HA, RD, and PS – and three character scales: self-directedness (SD), cooperativeness (C), and self-transcendence (ST). The dimensions of temperament reflect heritable responses to stimuli. The validity and reliability of the Swedish version of the TCI have been tested in clinical samples [Citation19]. Internal consistency for the TCI in this material was 0.895, as determined using Cronbach’s alpha.

Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report-Short Form (ETI-SR-SF)

The ETI-SR-SF is a self-report questionnaire that assesses childhood trauma in four trauma categories, general (T), physical (P), emotional (E), and sexual (S) trauma, using twelve, five, five, and six items, respectively, as well as a total trauma (TT) score [Citation20]. Frequency of exposure and impact on everyday life are recorded. For physical, emotional, and sexual trauma, perpetrator and age of onset are also recorded. The English version of the ETI-SR-SF has shown good validity and internal consistency [Citation20]. This was replicated for the Swedish translation used in this sample [Citation21].

Statistical analysis

The software R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for analyses [Citation22]. Significance value was a priori decided as p < .05.

The inter-rater reliability in this study was assessed using the PABAK [Citation23].

All BPD subjects that also had an ADHD or BD diagnosis were excluded from the sample in order to remove the need for covariate adjustment. Internal attrition within each instrument was investigated for the TCI (238 items), the ETI-SR-SF (28 items), and the SCID-II (nine criteria). Missing values were then imputed using a multiple imputation with the chained equation approach [Citation24]. All variables in the dataset were considered permissible as predictors for the variables that were to be imputed. Numeric values were imputed using predictive mean matching, with a logistic regression model used for binary variables, and a multinomial logit model used for factorial variables. The number of imputed datasets was set to five and convergence was assessed visually. The median of missing values was 1.3% among the studied variables and ranged between 0% and 18.5%. The median of missing values for each subject was 0%, with a range of 0–27%. Mean and standard deviation for each imputed variable were plotted against imputation number and if the lines intersected, convergence was considered to be achieved.

Differences between groups for gender and occupation status were assessed using Pearson’s chi-squared test; differences in age and mean number of anxiety disorders were assessed using the independent samples t-test.

Differences in responses to TCI items were first evaluated by computing differences in standardized mean score between the BPD and non-BPD group. Since the assumption of normality could be questioned, the median score for each group and the difference in location between the two groups were computed and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed.

Differences in response pattern regarding the ETI-SR-SF were assessed through computing frequency of endorsement and odds ratios (ORs) for the BPD group and the non-BPD group. This was done for each ETI-SR-SF item and sub-scale. Odds ratios were chosen since the separate ETI-SR-SF items are dichotomous. We performed a Poisson regression in order to compare the TT scores between the BPD group and the non-BPD group.

As theory testing, a logistic regression was performed with a BPD diagnosis as outcome variable, and the TCI temperament scales that significantly differed between the two groups, and the TT scores as predictors, controlling for gender. A power analysis was conducted based on the six independent predictors (sex, NS, HA, TT, HA:TT and NS:TT). Given a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), α = 0.05 and the power of 0.8 a minimal sample size of 97 participants was required. Therefore, this analysis was considered appropriate. Tjur’s D and Pseudo-R2 were calculated in order to assess explanatory power [Citation25,Citation26]. Bonferroni’s corrections were applied.

Ethical considerations

Study participants were all recruited from regularly psychiatric care. Three of the researchers were psychiatrists that worked at the clinic from where the participants were recruited, and had in many cases been their doctors. This could have made patients feel compelled to participate. Therefore, all invitations were sent by mail, so that patients could feel free not to take part. According to the numbers that never responded or did not show up, they seem to have felt free to deny participation. The trauma questionnaire was filled in last of all questionnaires and never by the participant left alone. All emotional reactions were taken care of by the interviewing psychiatrist. We also posted a questionnaire after they had participated, asking about their experience of participation, and among those who responded the majority was very positive. The study was approved by the Uppsala University Ethics Committee, Dnr 2008/171.

Results

Comparison of demographic variables between the BPD group (n = 19) and the non-BPD group (n = 95) is presented in . There was a significant difference in the mean number of Axis I and Axis II diagnoses between the groups, with the BPD group having more diagnoses on both axes.

The results of the comparison of the median TCI scores between BPD and non-BPD groups are presented in . The BPD-group showed higher NS and HA scores compared with non-BPD group.

Odds ratios for the four trauma categories of ETI-SR-SF with respect to the BPD and non-BPD groups are presented in , and computed ORs for all ETI-SR-SF items can be found in Appendix A. None of the general trauma scales generated a significant difference between the groups. However, two of the items of the ETI-SR-SF, ‘serious injury or illness of a sibling’ (T10) (OR = 4.56; 95% CI 1.61–12.09; p = .005) and ‘touched in intimate parts in a way that was uncomfortable’ (S5) (OR = 3.08; 95% CI 1.10–8.58; p = .032), were more often reported by the BPD group (see Appendix A). Utilizing a Poisson regression model where the TT score was regressed upon BPD, a significant difference in the mean TT score between individuals with BPD and those without BPD was observed. The non-BPD group had a mean score of 6.8, whereas the BPD group had a significantly higher mean score of 9.2 (p < .001).

We further investigated the theoretical hypothesis of the study, the potential interactive effect between HA, NS and TT, while controlling for sex. HA, NS and TT as well as their interaction effects were regressed upon the fulfillment of BPD diagnosis. None of the independent variables were significant predictors for a BPD diagnosis.

Results are shown in .

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine if psychiatric patients with BPD had higher levels of HA and/or NS and had experienced more childhood trauma compared with psychiatric patients with BD/ADHD. Moreover, the theoretic interaction between temperament and trauma in explaining a BPD diagnosis was explored. The results suggested that temperament in patients with BPD differed from that in patients with BD and ADHD, as they reported higher NS and HA. Traumatic experiences in childhood were similar in all participating patients and the BPD group differed very little from the others in that regard. No interaction between HA, NS and TT could explain the BPD diagnosis.

High NS and HA scores have previously been shown to enable distinction between individuals with BPD and individuals with other psychiatric disorders [Citation14]. A study that compared individuals with ADHD symptoms with individuals with combined ADHD and BPD symptoms, found that high HA was related to BPD symptoms while high NS was related to inattention symptoms of ADHD [Citation27]. The results from our study showed that even when compared with disorders such as BD and ADHD, patients with BPD had significantly higher levels of both HA and NS. This combination of fearful, anxiety-prone (HA) and impulsive, anger-prone traits leads to more anxious and angry reactions to emotions [Citation28]. This is in line with previous research that suggested that more pronounced affective temperaments are common in patients with BPD compared to patients with BD [Citation29]. Assessment of temperamental traits in patients with BPD might be useful when symptoms of impulsivity and affective instability are evaluated in psychiatric patients.

Studies evaluating the role of trauma in the development of BPD consistently report high prevalence of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse during childhood [Citation11]. Few studies compare the prevalence of childhood trauma between psychiatric patients with BPD and psychiatric patients with overlapping symptoms, even though trauma experiences are known to be increased even in these patients [Citation30,Citation31]. Mazer et al. [Citation32] reported more emotional abuse in childhood in patients with BPD compared with patients with BD. Ferrer et al. [Citation33] supported the association between childhood physical trauma and ADHD, while emotional abuse could be associated with BPD. Since traumatic experiences in childhood were common in both the BPD and non-BPD group, this could explain why the previous finding could not be replicated in this study, where all patients came from trauma burdened groups. Patients with ADHD and BD also experience more trauma when compared to non-disordered samples, which can make the differences smaller between the ADHD/BD group and the BPD group, thus also in this study [Citation34–36]. When BPD is compared with non-clinical controls, the difference in experienced trauma is large [Citation37] but when compared to, for example, patients diagnosed with PTSD, the difference is much smaller [Citation20]. The generally lower rates of trauma in Sweden might also have influenced the results. For example, Gerdner and Allgulander [Citation38] showed that both Swedish clinical and non-clinical samples rated lower trauma scores compared to American samples. In a study were ETI-SF-SR was used the pattern was the same with lower scores in Swedish samples [Citation20]. So even if it was very common among participants to have experienced trauma, the number of traumas was still lower than in studies from North America, and therefore, it was more difficult to identify differences between groups. However, the results suggest a difference in the mean TT scores between the two groups. This discrepancy could be explained by the impact of outliers when assessing mean scores and by the low sample size of our study. Therefore, caution is advised before translating this into the clinical setting and instead argue in favor of further studies with larger cohorts.

This study showed that there was significantly higher prevalence of one specific type of sexual abuse – having been touched in intimate parts – reported by individuals with BPD compared with those in the non-BPD group. This has not previously been reported. If it will be replicated in the future, the mechanism behind this association needs further investigation.

The BPD group had significant more Axis I and Axis II diagnoses than the non-BPD group. Several studies have previously addressed the high rates of comorbidity in individuals with BPD [Citation39,Citation40]. Adult patients with BPD are also at higher risk to be diagnosed with comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder [Citation41–43]. However, Eich et al. did not find any differences in Axis I comorbidity between adults diagnosed with BPD, BD and ADHD [Citation44]. One explanation for the finding in this sample could be that female individuals with BPD display higher rates of comorbidity for Axis I disorders [Citation45] and the BPD group consisted mostly of female patients.

Although there were significant differences between the groups in terms of the temperament scales NS and HA, our theory testing interaction model could not show any interactions between NS, HA and TT in explaining a BPD diagnosis. The interaction between temperament and environment is complex and many other both genetic and environmental factors are involved in the development of BPD. Our results indicate that childhood adversities are not specific for BPD and suggest that it might be the way traumatic experiences are processed based on the temperamental traits that might contribute to the development of the disorder. In spite of a negative interaction analysis, there is support in the literature for this theory, for example, in a study of individuals with BPD and their sisters, Laporte et al. showed that both probands and their sisters had similar childhood traumatic experiences but differed in personality traits leading to the suggestion that sensitivity to adverse experiences are influenced by personality profiles [Citation7]. In a longitudinal study by Bornovalova et al. examining the course and heritability of BPD, the results indicated that genetic factors highly influenced the stability of BPD traits while the influence of environmental factors was modest [Citation46].

The overall explanatory power of our explorative interaction model was 20%, indicating that there are more factors that influence the development of BPD in support of the multifactorial background to BPD development. Results from other interaction models are similar. Martin-Blanco et al. [Citation47] showed that two specific personality traits and emotional abuse accounted for 30% of the variance of BPD severity. In light of these results, it should be advisable for clinicians to refrain from using reductionistic models to explain BPD development and keep in mind the inherent complexity of the developmental pathways of the disorder.

Our study has several limitations. Our trauma questionnaire relied on retrospective data, which could have generated a recall bias. However, there is some evidence that supports the validity of retrospective recall of childhood trauma, as shown in a review article by Hardt and Rutter [Citation48]. Our logistic regression analysis model did not generate sufficient explanatory power, partly due to the fact that the two study groups had overlapping symptoms and partly due to childhood trauma being common in both groups. This sample was small and became even smaller when all participants with comorbid BPD/ADHD/BD were excluded according to the study design. Exclusion of patients with comorbidity may have led to a certain bias as there was an overrepresentation of patients with comorbid BPD/ADHD/BD in the excluded group of patients. That said, when the analyses were repeated including patients with comorbidity, similar results were retrieved (data not shown). Given the small size of our study, power issues are a limitation and generate an increased risk for false positives.

Another limitation is the use of a diagnostic interview for ADHD developed for children and adolescents, when our participants were young adults. When we started the study, there were no diagnostic interviews for ADHD in adults available in the Swedish language. Now, the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in adults (DIVA) has been translated, but it is still not psychometrically evaluated in its Swedish translation. Since K-SADS was well established as a diagnostic interview with good psychometric properties for adolescents up to 18 years, and our participants were still young we decided to use the K-SADS. Moreover, we assessed each diagnostic criterion based on the responses on the K-SADS questions. There were rich descriptions and clarifications provided by the participants on each item, since it is a semi-structured interview. It was experienced as easy to assess the diagnostic criteria based on the material. As part of the same project, the Swedish translation of Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) was validated [Citation49], and the diagnostic accuracy of the WURS vs. an ADHD diagnosis according to K-SADS was examined using AUC and ROC analysis, and the optimal cut-off score for WURS was 39, with a sensitivity of 0.88 and specificity of 0.70, with AUC 0.87, 95% CI 0.80–0.94. In a recent study that evaluated validity of DIVA in its Spanish translation, the same cut off 39 for WURS was used, and the results showed 83.9% with ADHD above cut-off (e.g. sensitivity) and 88.8% of those without ADHD below cut-off (e.g. specificity) [Citation50]. These figures are very similar and support the accuracy of our ADHD diagnoses.

The differences found between BPD, BD, and ADHD with respect to certain temperament traits and traumatic experiences are in line with earlier research. However, the interaction between temperament and trauma had low explanatory power for a BPD diagnosis in this sample and are not enough to distinguish BPD from ADHD and BD in this outpatient clinical setting. Finding more efficient factors for distinguishing between these groups could therefore be of interest in future studies.

Conclusion

Temperament but less childhood trauma distinguished the BPD group from the clinical non-BPD group. Assessment of temperament traits might be useful for clinicians in evaluating patients with affective instability and impulsivity. The interaction effects between NS, HA and TT did not explain a BPD diagnosis. Since this is a small sample, our analyses should be viewed as explorative and theory testing. Still, the explorative interaction analysis supports a multifactorial model of BPD development.

Author contributions

IK and MR conceptualized the research and its methodology, were involved in data collection and were major contributors to writing the original draft, reviewing and editing. HH curated the data, ran statistical analyses, and contributed to writing the original draft and reviewing the final version. LE contributed to conceptualizing the research, supervising and reviewing. All authors read, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Uppsala University Ethics Committee, Dnr 2008/171.

Consent form

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Niklas Hörberg for his valuable contribution to data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author [IK]. The data are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise research participant consent.

No funding sources.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ioannis Kouros

Ioannis Kouros, MD, PhD student in psychiatry at Uppsala University, Department of Medical sciences and Senior Consultant at the Department of Adult Psychiatry, Akademiska University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden.

Håkan Holmberg

Håkan Holmberg, statistician, at the time of the study working with the national health registers at at the National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden.

Lisa Ekselius

Lisa Ekselius, MD, PhD, Senior professor in psychiatry at Uppsala University, Department for Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Mia Ramklint

Mia Ramklint, MD, PhD, Professor in child and adolescent psychiatry at Uppsala University, Department of Medical sciences, and Senior Consultant at the Department of Child and adolescent psychiatry, Akademiska University Hospital, both inUppsala, Sweden.

References

- Javaras KN, Zanarini MC, Hudson JI, et al. Functional outcomes in community-based adults with borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;89:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.01.010.

- Temes CM, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice GM, et al. Deaths by suicide and other causes among patients with borderline personality disorder and personality-disordered comparison subjects over 24 years of prospective follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(1):18m12436. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12436.

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Linehan MM. A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(3):495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616.

- Ball JS, Links PS. Borderline personality disorder and childhood trauma: evidence for a causal relationship. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11(1):63–68. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0010-4.

- Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(12):975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008.

- Skoglund C, Tiger A, Rück C, et al. Familial risk and heritability of diagnosed borderline personality disorder: a register study of the Swedish population. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(3):999–1008. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0442-0.

- Laporte L, Paris J, Guttman H, et al. Psychopathology, childhood trauma, and personality traits in patients with borderline personality disorder and their sisters. J Pers Disord. 2011;25(4):448–462. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.448.

- Godbout N, Daspe M-È, Runtz M, et al. Childhood maltreatment, attachment, and borderline personality-related symptoms: gender-specific structural equation models. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(1):90–98. doi: 10.1037/tra0000403.

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Paris J. A prospective investigation of borderline personality disorder in abused and neglected children followed up into adulthood. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(5):433–446. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.5.433.

- Zanarini MC, Temes CM, Magni LR, et al. Risk factors for borderline personality disorder in adolescents. J Pers Disord. 2020;34(Suppl. B):17–24. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2019_33_425.

- Porter C, Palmier-Claus J, Branitsky A, et al. Childhood adversity and borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141(1):6–20. doi: 10.1111/acps.13118.

- Richard-Lepouriel H, Kung AL, Hasler R, et al. Impulsivity and its association with childhood trauma experiences across bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.060.

- Fassino S, Amianto F, Gastaldi F, et al. Personality trait interactions in parents of patients with borderline personality disorder: a controlled study using the Temperament and Character Inventory. Psychiatry Res. 2009;165(1–2):128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.10.010.

- Barnow S, Herpertz SC, Spitzer C, et al. Temperament and character in patients with borderline personality disorder taking gender and comorbidity into account. Psychopathology. 2007;40(6):369–378. doi: 10.1159/000106467.

- Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Baldassarri L, et al. The role of trauma in early onset borderline personality disorder: a biopsychosocial perspective. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:721361. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.721361.

- Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I disorders, clinician version (SCID-CV). Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1996.

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders: SCID-II. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021.

- Brandstrom S, Richter J, Przybeck T. Distributions by age and sex of the dimensions of Temperament and Character Inventory in a cross-cultural perspective among Sweden, Germany, and the USA. Psychol Rep. 2001;89(3):747–758. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.89.3.747.

- Bremner JD, Bolus R, Mayer EA. Psychometric properties of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(3):211–218. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243824.84651.6c.

- Horberg N, Kouros I, Ekselius L, et al. Early Trauma Inventory Self-Report Short Form (ETISR-SF): validation of the Swedish translation in clinical and non-clinical samples. Nord J Psychiatry. 2019;73(2):81–89. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2018.1498127.

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020.

- Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):423–429. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90018-v.

- Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn C. MICE: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Soft. 2011;45(3):1–67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

- Tjur T. Coefficients of determination in logistic regression models—a new proposal: the coefficient of discrimination. Am Stat. 2009;63(4):366–372. doi: 10.1198/tast.2009.08210.

- McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Frontiers in econometrics; New York [u.a.] : Academic Press -1974. p. 105–142.

- van Dijk FE, Lappenschaar M, Kan CC, et al. Symptomatic overlap between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and borderline personality disorder in women: the role of temperament and character traits. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.007.

- Cloninger CR. Psychobiology and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2002;14(2):60–65. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5215.2002.140202.x.

- Nilsson AK, Jørgensen CR, Straarup KN, et al. Severity of affective temperament and maladaptive self-schemas differentiate borderline patients, bipolar patients, and controls. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(5):486–491. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.02.006.

- Sugaya L, Hasin DS, Olfson M, et al. Child physical abuse and adult mental health: a national study. J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(4):384–392. doi: 10.1002/jts.21719.

- Durdurak BB, Altaweel N, Upthegrove R, et al. Understanding the development of bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder in young people: a meta-review of systematic reviews. Psychol Med. 2022;52(16):1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291722003002.

- Mazer AK, Cleare AJ, Young AH, et al. Bipolar affective disorder and borderline personality disorder: differentiation based on the history of early life stress and psychoneuroendocrine measures. Behav Brain Res. 2019;357–358:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2018.04.015.

- Ferrer M, Andion O, Calvo N, et al. Differences in the association between childhood trauma history and borderline personality disorder or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnoses in adulthood. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;267(6):541–549. doi: 10.1007/s00406-016-0733-2.

- Rucklidge JJ, Brown DL, Crawford S, et al. Retrospective reports of childhood trauma in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2006;9(4):631–641. doi: 10.1177/1087054705283892.

- González RA, Vélez-Pastrana MC, McCrory E, et al. Evidence of concurrent and prospective associations between early maltreatment and ADHD through childhood and adolescence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(6):671–682. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01659-0.

- McKay MT, Cannon M, Chambers D, et al. Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;143(3):189–205. doi: 10.1111/acps.13268.

- Alafia J, Manjula M. Emotion dysregulation and early trauma in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory study. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(3):290–298. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_512_18.

- Gerdner A, Allgulander C. Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short form (CTQ-SF). Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(2):160–170. doi: 10.1080/08039480802514366.

- Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Axis I diagnostic comorbidity and borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(99)90123-2.

- Kaess M, von Ceumern-Lindenstjerna IA, Parzer P, et al. Axis I and II comorbidity and psychosocial functioning in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology. 2013;46(1):55–62. doi: 10.1159/000338715.

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404.

- Zanarini MC, Athanasiadi A, Temes CM, et al. Symptomatic disorders in adults and adolescents with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2021;35(Suppl. B):48–55. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2021_35_502.

- Pagura J, Stein MB, Bolton JM, et al. Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the U.S. population. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(16):1190–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.016.

- Eich D, Gamma A, Malti T, et al. Temperamental differences between bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: some implications for their diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.028.

- Silberschmidt A, Lee S, Zanarini M, et al. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: results from a multinational, clinical trial sample. J Pers Disord. 2015;29(6):828–838. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_175.

- Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, et al. Stability, change, and heritability of borderline personality disorder traits from adolescence to adulthood: a longitudinal twin study. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(4):1335–1353. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990186.

- Martin-Blanco A, Soler J, Villalta L, et al. Exploring the interaction between childhood maltreatment and temperamental traits on the severity of borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(2):311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.08.026.

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x.

- Kouros I, Hörberg N, Ekselius L, et al. Wender Utah Rating Scale-25 (WURS-25): psychometric properties and diagnostic accuracy of the Swedish translation. Ups J Med Sci. 2018;123(4):230–236. doi: 10.1080/03009734.2018.1515797.

- Ramos-Quiroga JA, Nasillo V, Richarte V, et al. Criteria and concurrent validity of DIVA 2.0: a semi-structured diagnostic interview for adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(10):1126–1135. doi: 10.1177/1087054716646451.

Appendix A.

Odds ratios (or) for all ETI-SR-SF items predicting a BPD diagnosis in 114 psychiatric outpatients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) or not (non-BPD)

Figure 1. Flowchart of the recruitment process, starting with all psychiatric patients diagnosed with either borderline personality disorder (BPD), bipolar disorder (BD), and/or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) between May 2005 and October 2010, at a specific outpatient clinic.

Table 1. Descriptive data for the BPD group and the non-BPD group (BD/ADHD) in a young psychiatric sample.

Table 2. Comparison of median TCI scores for the BPD group and the non-BPD group in a young psychiatric sample.

Table 3. Odds ratios for the four trauma categories of the ETI-SR-SF predicting BPD in a sample of young psychiatric patients with BPD or non-BPD, the latter constituted by BD and/or ADHD.

Table 4. Results of the logistic regression of temperament and trauma on a BPD diagnosis.