Abstract

Introduction

In 2016, a new addiction treatment service, Allorfik, was introduced in Greenland. Allorfik has, throughout the implementation and after, used auditing of patient records with feedback to develop the quality of care in treatment. Audits and feedback are routinely done in each treatment center. This study wishes to investigate the development of the quality of treatment through the case notes from the journal audits.

Methodology

This study is based on case notes audits from 2019, 2020 and 2021. In the audits, the focus has been on the quality of documentation and content for ten specific areas in each patient record. Each area was scored on a Likert scale of 0–4 for both outcomes. Statistical analyses were done using Stata 17, and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We present baseline characteristics for patients and illustrate the development of quality for both outcomes as time trends with scatter plots.

Results

The analysis was based on data from 454 patients and audits of their case notes. The mean number of weeks in treatment is 12.72, and the mean age for the people in the audited case notes is 39. Time had a positive effect on both outcomes, and so each month, documentation increased by 0.21 points (p-value = <0.001), and content increased by 0.27 points (p-value = <0.001).

Conclusion

For documentation and content, the quality level has increased significantly with time, and the quality of case notes is at an excellent level at the final audits of all treatment centers.

1. Background

In 2015, a political consensus decision in Greenland led to the introduction of a new national treatment service for addiction to alcohol, cannabis, and gambling problems named Allorfik. Addiction problems have been a significant concern for health and social problems in Greenland for many years and were consequently high up on the agenda in the government’s public health strategy [Citation1,Citation2]. The Population Health Surveys in Greenland have continuously found a significant proportion − 35% to 52% – of the participants consume five or more drinks on the last occasion (binge drinking), and 22% to 29% consume possibly harmful levels of alcohol. The population health surveys have also documented a regular use of cannabis (> once per month) with 9–19% of the participants [Citation3,Citation4]. Gambling behavior is found in less than 10% of the population (ibid). However, it is still of concern since studies have found that lifetime gamblers are at high risk of cross-addictive behaviors such as harmful use of alcohol, frequent use of cannabis, or both [Citation5].

Allorfik started its establishment and implementation in 2016 [Citation6]. When Allorfik was implemented, it was with a clear purpose of delivering addiction treatment based on the available evidence and close to the people needing treatment [Citation7]. Addiction treatment was previously only available in one city. Thus, a large part of the population had to travel long distances or wait for a traveling counselor to visit their hometown for intensive treatment courses once a year or even on rare occasions. The new addiction treatment led to the implementation of five new out-patient treatment centers scattered over the country, training of new counselors, and implementation of new treatment methods, and this effort has continuously been supplemented with an option of intensive daily treatment through a partnership with a private provider of treatment (central treatment). The implementation process was a challenge, but according to the people involved, the addiction treatment currently delivered corresponds to what was intended [Citation8]. The treatment was based on the available evidence [Citation9,Citation10] and mainly consists of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy. New clients in treatment can enter treatment by direct contact with a treatment center or by referral from, e.g. a workplace, healthcare provider, or social worker in the municipalities. A standard outpatient treatment course in the present study consists of two weekly sessions for about 10–12 weeks.

In Allorfik, the treatment counselors were responsible for not only offering treatment but also for treatment registration and documentation. Documentation and data were needed if treatment quality was to be monitored and if it was a potential topic for quality development. However, when counselors were expected to perform documentation and registration alongside the treatment courses, differences in documentation practice and human errors may occur. Many counselors had no former practice with registration and documentation of treatment before working with Allorfik, so documenting was learned as part of the introduction training and utilizing repetitive training across the treatment centers. The counselors have very different backgrounds, experiences, and professional training, but many have a higher educational background, e.g. nurse, teacher, or social counselor. A few were trained in addiction treatment methods before employment with Allorfik. However, all those persons were trained in other treatment methods, as Allorfik introduced new methods (Motivational Interviewing) [Citation8]. There were at least three counselors in each treatment center, and the biggest center in Nuuk had six counselors employed. All treatment centers had a local group leader; some centers had a secretary/administrative assistant and/or interpreter employed. In the first years of implementation, staff had a high turnover [Citation8]. In July 2020, a new and improved treatment guideline was introduced to all treatment facilities within Allorfik. The guidelines aimed at being easy to follow for all counselors and hence increase compliance and documentation of the treatment courses, as well as improve the treatment courses experience for the patients in treatment. The new guideline simplified the instructions for counselors with guidelines that were easier to read and follow. At the same time, WHO-5 screening was introduced at the start of the treatment [Citation11].

Examination of quality performance data, describing the quality of the treatment delivered at a given time point, can be performed in many ways. Auditing is one method to perform systematic examinations of, e.g. patient records to determine the quality of care [Citation12]. Audits followed by feedback to the professionals is a widely used method to improve professional practice [Citation13] and an example of tools used in quality assurance work. Audit and feedback have been found to be effective in improving professional practice in some cases and the effects of doing audit and feedback are found to be small to moderate [Citation13]. Audit and feedback have been used in outpatient treatment for alcohol addiction in Denmark [Citation14], in addition to many other health sectors [Citation13]. External expert audits can be constructive in the development of quality as therapists have been found to over-rate their competence in therapy [Citation15]. Quality of care is also a focus area in the Greenlandic healthcare system, and quality is clinically monitored for chronic patients observed at the hospitals in Greenland with, e.g. diabetes or lung disease [Citation16,Citation17]. However, so far, no reports on performing Audits and feedback as a method for quality development in Greenland have been found. However, Nexøe and colleagues used an audit questionnaire when investigating alcohol- and violence-related healthcare visits [Citation18].

Throughout Allorfiks’ implementation process, quality of care has been sought secured, and improved by employing an external expert to systematically perform journal audits and give feedback to treatment counselor teams and management. This study wished to explore the development of the quality of care based on data stemming from these case notes. The hypothesis was a positive development of quality of care in treatment with the continued work to secure this.

2. Materials and methods

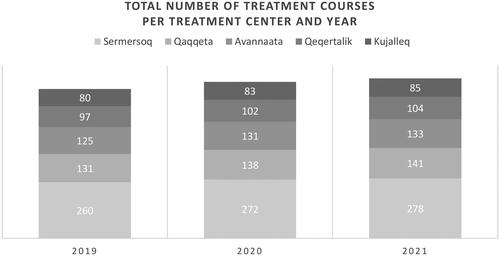

The number of referred patients and completed treatment courses in Allorfik has increased yearly. was based on the Annual reports from Allorfik and displays the number of treatment courses conducted each year and the share of patients per treatment center (both in the local Allorfik centers and as in-patient treatment courses with a private provider, central treatment) [Citation19–21]. The patients in local treatment offered by Allorfik were more often women with employment and a family, and the majority are younger people aged 25–34 years, whereas, in central treatment in Nuuk, there was more equal distribution in gender; few have family obligations, and all have a more substantial addiction pattern [Citation22]. The majority of people in treatment struggled with alcohol addiction however a significant proportion had a mix of addiction problems [Citation20].

2.1. The instrument included in the audits

Each person entering treatment would, after three sessions (initiation, visitation, and motivation), complete an assessment of the severity of the addiction and its adverse effects on various aspects of life using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) [Citation23] in a translated Greenlandic version and the WHO5 questionnaire on well-being [Citation24]. The ASI was repeated in a shorter version after six weeks of treatment, and both ASI and WHO5 are again repeated at the end of treatment. The data collected using these instruments were, in addition to being used directly in the clinical work in treatment, also used in the assessment of the quality of care.

2.2. Audit of case notes

Audits of case notes and feedback were and are continuously performed routinely in each Allorfik treatment center and based on a random sample of case notes from treatment courses concluded within the last year with status as ‘finished’ treatment courses. The purpose was to provide feedback to all counselors in each treatment center and provide feedback to the team on the quality of treatment courses conducted. The methods were inspired by what has been used to monitor the quality of care in the Danish [Citation25] and the English [Citation26] healthcare systems for many years. The present study was based on case note audits performed in 2019, 2020, and 2021. With the last local treatment center established in mid-2018, the study excluded journal audits from before the implementation of local treatment centers was completed.

The audits focused on the quality of the documentation and content in the case notes for ten specific areas:

Preliminary interview

Visitation

Motivational Interview

ASI base screening

WHO5 base screening

Treatment

Psychoeducation

ASI at six weeks

ASI end screening

WHO5 end screening

For each area, a quality assessment was made according to a manual describing the requirements for good quality in both documentation and content, as appeared in the case notes. For documentation, the assessment was based on whether a registration of action was noted in the case notes and in the proper order for the treatment course. For content, the assessment was based on a predefined description of what was required for the area in question to attain excellent quality of care. The areas, manuals, and requirements for quality were chosen and described in collaboration with a management team from Allorfik.

The assessment was performed by one external expert, visiting Allorfik. The external expert was an acknowledged professor in psychiatry with extensive experience in addiction treatment services, auditing of case notes, and quality development from both the outpatient treatment of addiction services and psychiatry in Denmark. The external expert conducted assessments for Allorfik in the period from September 2016 to April 2022. During this period audits of case notes from a series of treatment courses and feedback visits were performed three times for each of the five treatment centers. Each time, the audits of case notes were followed by a feedback visit at the treatment enter. An audit of case notes for one treatment course lasted 15–30 min and the assessment was done in concordance with the manual. The case notes were randomly chosen among treatment courses performed at the treatment centers, having a status of being ‘finished’ within a period of three months prior to the feedback visit of the external expert and approximately half of all the courses performed in the period was assessed. Feedback to the staff at the treatment center, based on the assessment of case notes, was provided during the external expert’s visit to the treatment centers. The external expert would typically visit for one week.

Each area was scored on a Likert scale of 0–4 for both documentation and content. The individual journal score values were interpreted according to the recommendation of the national quality program for the health sector [Citation25]. Scores 0 and 1 meant unacceptable quality requiring supervision and control. The score 2 was what you would typically see after a start-up period, but it would still be essential to support a culture of improvement so that the quality can be further improved. A score of 3 or 4 indicated excellent quality with an essential culture of improvement, which could create the basis for new initiatives to raise the quality even further.

Due to the COVID-19 epidemic, Greenland closed its borders to outsiders throughout 2020; thus, no feedback visits were conducted. Instead, an extra-large proportion of journals were audited, and feedback was provided through online meetings in 2020.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The patient’s baseline characteristics (age, treatment center, and number of weeks in treatment) were presented as counts (percentages (%)), means, and median when appropriate. Time trends were illustrated with a scatter plot of the quarterly development of quality of care for both documentation and content in each of the local Allorfik treatment centers.

To show the development of quality of care in treatment, data was modelled using an interrupted time series approach, similar as described in Wagner, A.K., et al. from 2002 [Citation26]. We used linear mixed models for both outcomes (documentation and content) to account for repeated measures per treatment center over time.

Fixed effects in the model included time (continuous, measured in days), new treatment guidelines in 2020 (binary, 0 before, one after), and treatment center (categorical). For each of the two outcomes, we tested for an interaction term between time and new guidelines to investigate a change in trend over time before or after the intervention and also for interaction between town and new guidelines to examine whether the different treatment centers differ in the effect of the intervention. These interactions were evaluated using the likelihood ratio test to investigate improved model fit, but no interaction was significant in any model.

We included a random intercept per local treatment center in the models. Including a random slope did not improve model fit and was thus not added in the final models. Because the assumption of normality of residuals was violated for both models, we employed bootstrapping with 1000 replications to estimate standard errors and confidence interval bounds of the regression coefficients. We checked normality assumptions by visual inspection. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant, and we conducted all statistical analyses using Stata 17 (StataCorp, College Station; TX, USA).

3. Results

The analysis was based on data from audits of case notes from 454 randomly chosen patients. The case notes include 82 journals of treatment courses in 2019 (11% of the total number of treatment courses this year), 302 journals from treatment courses in 2020 (41% of the total number of treatment courses this year), and 70 journals courses of treatment in 2021 (9% of the total number of treatment courses this year) for the analysis. The mean number of weeks in treatment was 12.72, and the mean age for the people in the audited case notes was 39 years. The distribution of case notes, patient age, and treatment durations were shown in .

Table 1. Distribution of the number of patients and median age and weeks in treatment per year.

3.1. Time trends

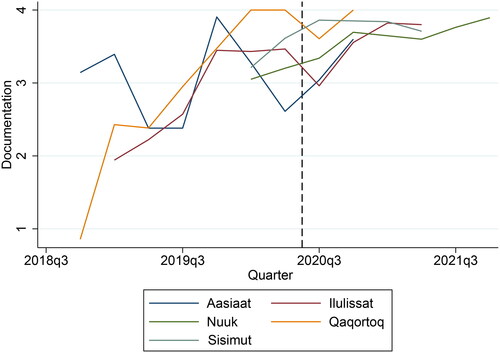

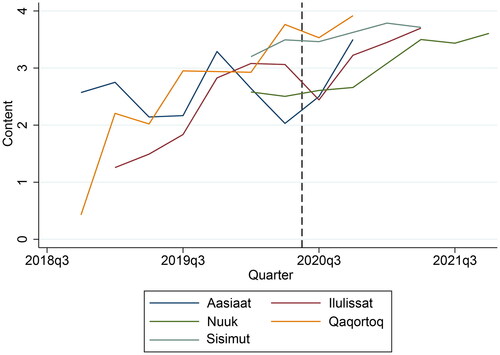

illustrated how the accumulated quality score of the documentation steadily increased over time in each treatment center. In , the same pattern was seen for the quality score of the content in each treatment center. and also illustrated an equally high-end level of documentation and content for all treatment centers.

Figure 2. Quarterly development in documentation for each treatment center with the 2020 guideline update marked with the dashed line.

Figure 3. Quarterly development in content for each treatment center with the 2020 guideline update marked with the dashed line.

As illustrated in and , no audits were performed in Nuuk and Sisimiut in 2019, and their starting points in the 2020 audits were at the same level as the other treatment centers. Furthermore, no audits were performed in Qaqortoq and Aasiaat in 2021. Still, the final audits for all treatment centers in 2020 and 2021 showed how the quality of content and documentation levels were almost the same across all centers.

3.2. Mixed effects

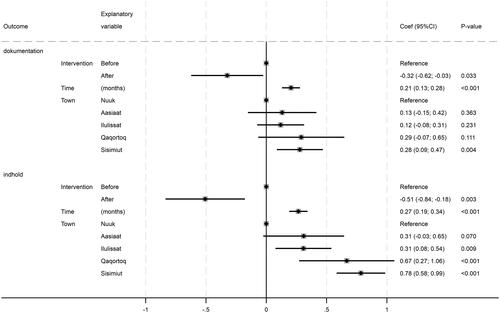

A multilevel mixed-effect linear regression model was performed to test if the positive trends were significant and if the updated guideline in 2020 (intervention) implementation might explain the development in documentation and content. The results can be seen in with a forest plot of the regression model.

Figure 4. Forest plot of results from a mixed linear regression illustrating the development of quality in documentation and content and how time, treatment center, and the 2020 intervention (a new treatment guideline) have affected the quality development.

shows that after the 2020 intervention with a new treatment guideline, the quality of case notes on documentation decreased by 0.32 points and 0.51 points for content, and the decreases were significant (p-value = 0.033 and 0.003). Time had a positive effect on both outcomes, and so each month, documentation increased by 0.21 points (p-value = <0.001), and content increased by 0.27 points (p-value = <0.001). also shows that with Nuuk (the largest center in the capital) as the reference, all other centers have a higher level of quality in case notes for both documentation and content.

4. Discussion

The present study illustrated that the quality of care in the treatment documented in the case notes in Allorfik, Greenland, has significantly improved over time and that the improvements were seen in both documentation and content. The introduction of a new treatment guideline - with the intent of improving the quality of treatment for the patients and improving the workflow for treatment counselors - did not explain the improvement in the quality, as the trends of improvement in quality did not differ before and after the introduction, and no interaction was found between time and intervention. This short decline might reflect how the treatment counselors became acquainted with the new guidelines. Still, the continued focus on quality improvement was probably what secures an ongoing positive development of quality of care unaffected by the monetarily fall in mid-2020.

With the local treatment centers having been implemented over several years, it might be expected that the quality of the treatment was higher in the treatment centers first established, e.g. Qaqortoq or Nuuk, since they would have had a longer time to develop a good quality than the newest treatment centers in Aasiaat. However, this did not seem to be the case with the high and matching end levels of documentation and content across the treatment centers.

Since the quality level did not seem to be dependent on the specific treatment center, it thus must have been related to other factors, for example, the qualifications of the individual treatment counselor. This study had no information on the individual counselors, as the journal audits did not include this information. The purpose of the case note audits was not to give personal feedback to each counselor but to work with all counselors in each treatment center as a team. The experiences on feedback from other studies are mixed, and the recommendation is to provide feedback either to individuals or groups and that a higher effectiveness is achieved with feedback delivered more intensively [Citation13]. And that tailored comparison is preferred from benchmarking against the mean [Citation12]. Evidence have also supported the effects of audits and feedback to be possibly more significant when the professionals re actively involved and had specific and formal responsibilities for implementing change [Citation13]. The average period of employment for each counselor varies as there has been a high turnover in staff in all Allorfik centers [Citation8]. With the high turnover in staff, it could have been speculated if the quality of treatment would have improved over time, and perhaps we would not have seen an improvement in quality if the study had focused on the first year’s audit and feedback while the implementation and establishment were still ongoing. However, as this study found a significant improvement in the quality of care in treatment, we hypothesize that the ongoing work with audit and feedback has had an effect that was not disturbed by the turnover in staff in the implementation period.

Audits and feedback have been used throughout the implementation of Allorfik and are still used after the implementation has ended. Thus, working with quality development of treatment is continuously being performed. The results of this study indicate that this strategy has been successful since the end level of the quality of treatment is high in all treatment centers. A sub-study of the present study also found that continued focus on quality in treatment has contributed to the successful implementation of Allorfik [Citation8]. There were no other examples found of audit and feedback from a Greenlandic context; however, this study could be an inspiration for others working with the quality of treatment and/or implementation of a new intervention.

One external consultant performed the audits and provided feedback on case notes, which could provide a limitation. However, as the areas and requirements for good quality were chosen by management, this could instead be a strength as one person performing the audits and feedback also provides excellent consistency. Quality of care in treatment could also be studied in other ways, e.g. observation of counseling sessions or group supervision, which would give different perspectives on developing quality of care in treatment. However, this was not feasible in this study but could inspire future studies.

5. Conclusion

For documentation and content, the quality level has increased significantly with time, and the quality of case notes was at an excellent level in all treatment centers at the final audits in 2020 and 2021. This indicates a basic internal culture of improvement and quality, providing an opportunity for new initiatives to improve the quality of care even further in Allorfik.

Ethical approval

The study has been approved by the National Board of Health in Greenland

Disclosure statement

Birgit Niclasen is the director of the National Addiction Treatment Services, Allorfik, but has never handled the audits of case notes used for this study or contributed to the analysis or results of this manuscript. Birgit’s contributions to the manuscript are conceptualization, supervision, and validation. The authors, therefore, declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Data management and -storage were handled by the Open Patient Data Explorative Network. The dataset can be shared upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Julie Flyger

Julie Flyger has a background in public health and as a researcher she has been interested in addiction problems and treatment services in Greenland.

Anna Mejldal

Anna Mejldal is a biostatistician. Anna have worked with varies types of projects and have published in numerous peer-reviewed journals and her specialty is in epidemiology of persons with alcohol addiction.

Bent Nielsen

Bent Nielsen is professor MSO in psychiatry. For many years, he has researched the treatment of patients with alcohol problems and quality development in psychiatry. Has received the Quality Award from the Danish Society of Quality of Health for his work with quality development.

Birgit Niclasen

Birgit Niclasen is a trained doctor with a phd in public health. She is the principal investigator for the HBSC survey in Greenland and has published in many peer-reviewed journals. For many years she has worked as the director of Allorfik.

Anette Søgaard Nielsen

Professor Anette Søgaard Nielsen, MA, PhD, works at the University of Southern Denmark. Her research interest is primarily focused on treatment for alcohol use disorders. She has been heading several randomized controlled trials, surveys and qualitative studies in the field. She has published more than 150 peer-reviewed papers and a series of text-books and book chapters about primarily addiction, treatment, Motivational Interviewing, alcohol culture and narrative medicine.

References

- Departement for Sundhed. Inuuneritta 3. Naalakkersuisuts strategi for samarbejdet om det gode børneliv 2020-2030. [Inuuneritta 3 - The government of greenlands strategy for cooperation on the good life of children 2020-2030]. 2020: nuuk, Greenland.

- Departement for Sundhed. Inuuneritta 2 - Naalakkersuisuts strategier og målsætning for folkesundheden 2013-2019. [Inuuneritta 2 - The government of greenlands strategy and aims for the public health 2013-2019]. 2012: nuuk, Greenland.

- Larsen CVL, et al. Befolkningsundersøgelsen i grønland 2018. Levevilkår, livsstil og helbred - oversigt over indikatorer for folkesundheden. In SIF’s Grønlandsskrift [The Population Health Survey in Greenland 2018]. 2018, Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, SDU.

- Dahl-Petersen IK, et al. Befolkningsundersøgelsen i grønland 2014/kalaallit nunaanni innuttaasut peqqissusaannik misissuisitsineq 2014: levevilkår, livsstil og helbred/inuunermi atugassarititaasut, inooriaaseq peqqissuserlu. In SIF’s Grønlandsskrifter [The Population Health Survey 2014]. 2016, Syddansk Universitet. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed.

- Larsen CV, Curtis T, Bjerregaard P. Harmful alcohol use and frequent use of marijuana among lifetime problem gamblers and the prevalence of cross-addictive behaviour among Greenland inuit: evidence from the cross-sectional inuit health in transition Greenland survey 2006-2010. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(1):19551. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.19551.

- Flyger J, et al. Wishing for a sober society: a scoping review on abusive behavior and addiction treatment services in Greenland prior to deciding the current national strategy for treatment for addiction in Greenland. Manuscript submitted for publication, 2023.

- Departement for Sundhed og Infrastruktur. Forslag til national plan for fremtidens misbrugsbehandling., [Proposal For a National Plan for Future Substance Abuse Treatment]. 2015: nuuk.

- Flyger J, et al. A qualitative study of the implementation and organization of the national greenlandic addiction treatment service. Manuscript submitted for publication, 2023.

- Nice. Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence | guidance and guidelines. | NICE. 2011, NICE.

- Danish Health authority. National clinical guideline on treatment of alcohol dependence. 2018. Copenhagen: The Danish Health authority. p. 161.

- Topp CW, Østergaard SD, Søndergaard S, et al. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–176. doi: 10.1159/000376585.

- Gude WT, Brown B, van der Veer SN, et al. Clinical performance comparators in audit and feedback: a review of theory and evidence. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0887-1.

- Jamtvedt G, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes cochrane. Database of Syst Rev. 2006;(6).

- Nielsen AS, Nielsen B. Implementation of a clinical pathway may improve alcohol treatment outcome. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0031-8.

- Brosan L, Moore RG, Reynolds S. Self-evaluation of cognitive therapy performance: do therapists know how competent they are? Behav Cognit Psychother. 2008;36(05):581–587. doi: 10.1017/S1352465808004438.

- Lauridsen MV, et al. Prevalence and quality of care among patients using medication targeting obstructive lung disease: a cross-sectional study in the five regions of Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2021;80(1):1948244.

- Pedersen ML. Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Greenland, 2008: examining the quality and organization of diabetes care. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68(2):123–132. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i2.18322.

- Nexøe J, Wilche JP, Niclasen B, et al. Violence- and alcohol-related acute healthcare visits in Greenland. Scand J Public Health. 2013;41(2):113–118. doi: 10.1177/1403494812469852.

- Allorfik. Årsrapport 2019. [Annual Report 2019]. 2020: nuuk.

- Andersen C, Schou M, Niclasen B. Årsrapport 2021. [Annual Report 2021]. 2022. Allorfik: nuuk. p. 1–58.

- Niclasen B, Sommerlund K, Povlsen F. Årsrapport 2020. [Annual Report 2020]. 2021. Videnscenter om Afhængighed: nuuk. p. 1–37.

- Flyger J, Nielsen B, Niclasen BV, et al. Does establishing local treatment institutions lead to different populations seeking treatment among greenlandic inuit? Nord J Psychiatry. 2019;74(4):259–264. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2019.1696887.

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. p. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s.

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the DepCare Project: report on a WHO meeting: Stockholm, Sweden, 12–13 February 1998. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/349766

- Ministeriet for sundhed og forebyggelse. Nationalt kvalitetsprogram for sundhedsområdet 2015–2018 [National quality program for the health sector 2015–2018]. 2015: ministeriet for sundhed og forebyggelse. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Ministry for Health.

- Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x.