Abstract

Background

Brief Admission by self-referral (BA) is a crisis-management intervention standardized for individuals with self-harm at risk of suicide. We analyzed its health-economic consequences.

Materials and methods

BA plus treatment as usual (TAU) was compared with TAU alone in a 12-month randomized controlled trial with 117 participants regarding costs for hospital admissions, coercive measures, emergency care and health outcomes (quality-adjusted life years; QALYs). Participants were followed from 12 months before baseline to up to five years after.

Results

Over one year BA was associated with a mean annual cost reduction of 4800 or incremental cost of 4600 euros, depending on bed occupancy assumption. Cost-savings were greatest for individuals with >180 admission days in the year before baseline. In terms of health outcomes BA was associated with a QALY gain of 0.078. Uncertainty analyses indicated a significant QALY gain and ambiguity in costs, resulting in BA either dominating TAU or costing 59 000 euros per gained QALY.

Conclusion

BA is likely to produce QALY gains for individuals living with self-harm and suicidality. Cost-effectiveness depends on targeting high-need individuals and comparable bed utilization between BA and other psychiatric admissions. Future research should elaborate the explanatory factors for individual variations in the usage and benefit of BA.

Introduction

Self-harm – deliberate, damaging actions directed at one’s own body [Citation1] – is a risk factor for suicide [Citation2] and a key feature of borderline personality disorder (BPD) [Citation3]. The consequences of self-harm are substantial, including personal suffering, societal losses due to disability and life years lost [Citation4], and high hospital care costs, especially for individuals admitted to intensive care due to use of particularly dangerous methods. A minority of individuals with repeated care due to self-harm appears to account for a significant percentage of total hospital care costs [Citation5]. Accordingly, there is a need for evidence-based, systematic, and cost-effective actions to address the personal and societal burden of self-harm and suicide [Citation6].

Besides interventions for longer-term management, such as dialectical behavior therapy (which has demonstrated cost-effectiveness) [Citation7], there is a demand for effective crisis management interventions that meet the needs of individuals with self-harm at risk of suicide [Citation8]. Brief Admission by Self-referral (BA) is one of the few such standardized interventions supported by a randomized controlled trial (RCT) [Citation9,Citation10]. Individuals with access to BA may self-refer to a psychiatric ward when they feel that a crisis is imminent, to prevent a relapse or just to take a break when they feel they need extra support. BA aims to offer predictability and early recovery without jeopardizing autonomy [Citation9], reducing the risk of iatrogenic effects due to loss of control and coercion during emergency admissions [Citation11]. A 12-month RCT [Citation9] showed no significant change in the total number of days on hospital admission when providing BA alongside treatment as usual (TAU) compared to TAU alone, and inconclusive differences in disability based on the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) [Citation12]. The health-economic consequences of BA are not yet known.

Self-referral programs such as BA are part of an ongoing shift within psychiatric care towards agency and autonomy. Offering decision power to self-refer means providing hospital care without gatekeeping, in a setting where clinicians traditionally perform assessments to allocate a limited number of inpatient care beds according to need [Citation13]. Furthermore, BA requires high availability to meet needs as they arise. In a publicly funded health system, self-referral may raise ethical questions such as risk of displacement effects when some hospital admissions are not based on physician-assessed needs and current availability. Analyzing the cost-effectiveness of an intervention compared to relevant alternatives, utilizing measures of clinical effects, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), and economic costs, can offer valuable information to both clinicians and policymakers [Citation14].

We analyzed the cost-effectiveness of BA for individuals with self-harm at risk of suicide using data from a 1-year RCT [Citation9]. Additionally, we analyzed costs and outcomes before, during and after the trial using health register and follow-up data from four psychiatric health care facilities in southern Sweden.

Materials and methods

We followed standard methods for economic evaluation of healthcare [Citation14] utilizing patient-level data collected before, during, and after a 12-month RCT [Citation9]. The RCT (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02985047) including the four-year follow-up, received ethical approval (2014/570, 2016/10 and 2016/81, Lund, Sweden) and informed consent from participants.

Participants and setting

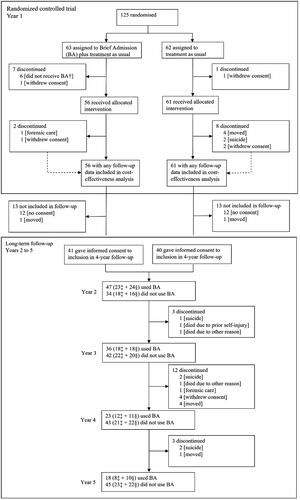

This study was conducted during 2015–2022. The RCT, conducted 2015–2018, has been reported elsewhere [Citation9]. Participants were randomized to have access to BA plus TAU (intervention group) or to TAU alone (control group) for 12 months, after which they were invited to a four-year follow-up wherein both groups had access to BA. All randomized individuals with any follow-up data were included in the analysis. Participants (n = 117) were 20–54 years with a mean age of 32 years (standard deviation 9) including 98 (84%) females, 14 (12%) males and five (4%) others based on self-reported gender identity. Ethnicity data was not collected. They were treated at one of four psychiatric inpatient clinics in Scania, southern Sweden (population 1.4 million), due to ongoing episodes of self-harm and/or recurring suicidality with at least three criteria for BPD. Participants had to have had at least seven days of psychiatric admission or three visits to a psychiatric emergency care unit during the six months before baseline. shows the participant flow.

Brief admission by self-referral (BA) and treatment as usual (TAU)

BA was provided according to a structured manual of strategies to enhance treatment fidelity [Citation15]. After an individualized contract negotiation aiming to guide BA in terms of goals, needs and when to self-admit, individuals with BA could self-admit for up to three nights, thrice per month. Individuals decided themselves when to use BA. During admission, they had to bring their own medication and remain responsible for their own safety. They were offered two daily supportive meetings with unit staff, but no meetings with physicians, psychologists, or other health care staff. Individuals were free to leave the unit during the day, such as to attend outpatient care or do other activities of their choice. Acts of self-harm led to discharge from the current BA but did not affect future access. After discharge due to self-harm, the individual was walked over to the emergency care unit and assessed by a physician who either let them go home or provided admission as a general psychiatric inpatient [Citation16].

Having a BA contract was provided in addition to TAU, both within the RCT and after, and did not affect access to other psychiatric care resources. TAU included for example regular contact with an outpatient psychiatric clinic and access to acute psychiatric care when needed.

During the RCT, BA was only provided at units that offered psychiatric emergency admission. After the RCT, designated BA-units were created at some clinics, while others continued providing BA at units with psychiatric emergency admissions.

Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)

QALYs were calculated based on WHODAS 2.0 scores [Citation12], using the validated country-independent mapping function on selected domains to estimate disability weights [Citation17,Citation18] (Supplement 1). Conversion was done without demographic adjustments since the analysis was based on randomized groups, without systematic differences in background variables observed between the randomized groups [Citation9]. WHODAS, which evaluates functioning and disability in the previous 30 days, was assessed at RCT baseline, after 6 months, 12 months, and 5 years. WHODAS scores during the RCT were assumed to represent the prior period between measurements. Missing data were imputed according to the WHODAS 2.0 manual [Citation12], such that when one or two items were missing, the mean domain score for that participant was imputed; if more than two items were missing, the participant was omitted. Utility weights to estimate QALYs during the RCT were estimated by subtracting the disability score from 1 and multiplying by the time expressed in years between WHODAS measurements. Participants who died due to self-harm and suicide were given a utility weight of zero, assuming no health utility from that point onward, to account for potential effects on QALYs in the analyses [Citation19].

Days admitted to hospital and related costs

Days in hospital were collected from medical records in six-month intervals from one year before baseline to five years after (six years in total), including care at a psychiatric clinic (voluntary care, compulsory care, and BA) and inpatient care days at other clinics if related to self-harm or suicidality. Additionally, type, duration, and number of coercive measures and emergency care visits related to psychiatric care or treatment of self-harm/suicidality at other clinics were collected. SW (RCT principal investigator) reviewed medical records and included all condition-related health care utilization at non-psychiatric clinics (Supplement 2). At the time this study started, SW had 14 years of experience in psychiatric care and had worked for 10 years in self-harm and suicide prevention.

Healthcare resource use was transformed into costs by multiplying quantities with the estimated unit price. Unit prices were based on real prices for resource inputs in 2020 at representative departments of Lund University Hospital (one of the four clinics in Scania). Price per admission day of BA was based on data from a designated BA-unit with 8 beds which opened in 2020 (Supplement 3 provides cost breakdown of this unit in 2020). Price per admission day for emergency psychiatric inpatient care was based on data from a 16-bed unit at the same clinic. The price per psychiatric emergency care visit was estimated using the emergency care unit in the same building.

The price per psychiatric admission day was calculated in two ways. In the base case, prices were based on actual bed occupancy rates during 2020, which was 49% at the BA unit and 115% at the emergency psychiatric care unit. In a capacity-adjusted scenario, calculations were based on an estimated annual average bed occupancy of 85% in both units; this is generally considered a safe bed occupancy rate in emergency care and a relevant goal for the dimensioning of BA units [Citation20].

Costs related to treatment of self-harm at non-psychiatric clinics were based on available regional price lists. Costs were converted from Swedish crowns (SEK) to euros using the annual average exchange rate for 2020 according to Sweden’s central bank (€1 = 10.49 SEK). See .

Table 1. Unit prices and cost calculation of hospital care in euros, 2020.

Choice of outcome measures

The cost-effectiveness analysis based on data from the RCT measured cost per QALY gained. Measuring health outcomes in QALYs was considered likely to be more useful to decision-makers compared to measures of natural units related to the objective of an intervention, due to the generic nature of QALYs incorporating value and combining effects on morbidity and mortality. The measure is widely used in health-economic evaluations, allowing for broad comparison and providing information on opportunity costs of a new intervention [Citation14]. Measuring cost per QALY gained means that cost and outcome are considered jointly. The impact or meaning of any change in cost per QALY gained will depend on the willingness to pay per QALY. Utility weights for calculating QALY were derived from WHODAS 2.0, which is freely available in more than 30 languages with satisfactory psychometric properties, hereunder the Swedish version [Citation12,Citation21].

The long-term follow-up, lasting up to five years after the baseline of the RCT, was based on the use of inpatient services as this was the primary outcome of the underlying RCT. Related costs were calculated to provide information on economic consequences.

Analysis

The analysis was based on all participants with any follow-up data (n = 117; 56 in the intervention group, 61 controls) (). Separate analyses were conducted for the RCT (within-trial analysis) and 4-year follow-up. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27 [Citation22].

The cost-effectiveness analysis involved calculating QALYs for BA + TAU and TAU alone for the within-trial period and comparing these to additional costs. To manage the expected individual-level variation in costs, a difference-in-difference strategy was used. Health care costs during 12 months before RCT baseline were used as reference and subtracted from the costs observed within the RCT period. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of BA versus TAU was defined as the difference in costs relative to the difference in QALYs, calculated as the difference in the area under the curves according to a conventional approach [Citation14]. Subgroup analyses involved comparing results according to available cases, complete cases, and individuals with less than 180 admission days the year before the RCT.

In the long-term follow-up, inpatient care days, costs and health utility were followed for all participants because they all had access to BA after the RCT.

Uncertainty analysis and handling of missing data

To assess the uncertainty of cost-utility results from the RCT, non-parametric bootstrap resampling based on 1000 iterations of individual-level cost/QALY pairs were applied [Citation23]. Scatter plots were created to illustrate the simulated distribution of mean differences in costs and outcomes. These were used to translate results into cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, showing the probability of BA being cost-effective at different levels of willingness to pay per QALY gained. Multiple imputation was used to address missing data for calculating QALYs, assuming that data were missing at random (i.e. systematic differences between missing and observed values can be explained by differences in observed data) [Citation24]. In the imputation models, age, educational level, BPD, and sex were used as auxiliary variables, as in the RCT [Citation9].

Role of the funders

None of the organizations contributing with funding had any role in the present work or any influence of its results or the interpretations of the findings.

Results

Within-trial cost-effectiveness

When comparing the two groups during the RCT, base case calculations indicated a cost increase of 4600 euros in average annual cost per participant in the BA group compared to controls, while the capacity-adjusted scenario with prices based on estimated availability instead indicated a cost reduction of 4800 euros per participant (). Alongside a gain of 0.078 QALYs (), the cost per QALY gained was 59 000 euros for BA versus TAU in the base case (). BA was cost-saving in the capacity-adjusted scenario ().

Table 2. Estimated treatment cost before and during randomized controlled trial (in euros based on 2020 prices; n = 117).

Table 3. Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) during 1-year randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Table 4. Cost-effectiveness of Brief admission by self-referral as add on to usual care compared to usual care alone (2020 prices in euros).

Individuals with extensive psychiatric care before the RCT (>180 admission days in the year before the RCT; n = 16, nine randomized to BA) accounted for 39% of costs during the year before the RCT and 24% during the RCT. When excluding these individuals (suggesting a potentially less severe subgroup), the cost per QALY gained increased to 119 900 euros in the base case and to 16 500 euros in the capacity-adjusted scenario. In a complete case analysis (n = 37), BA outmatched TAU in all scenarios.

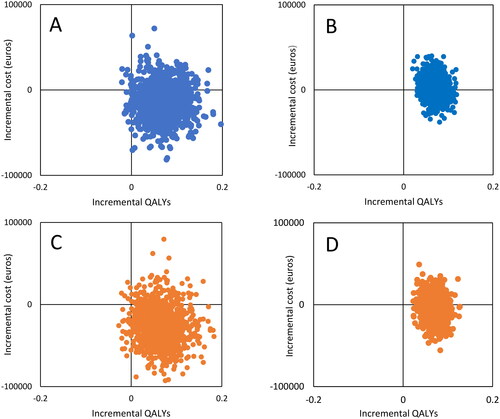

Uncertainty of within-trial cost-effectiveness

Scatter plots of the 1000 bootstrap replications of incremental costs and QALYs gained with BA compared to TAU illustrate the uncertainty of the results in a cost-effectiveness plane based on complete cases (n = 37, : boxes A and C) and all cases (n = 117) (boxes B and D). In the latter, multiple imputation was used for missing values of health utility because attrition analyses indicated no significant differences between the groups in baseline variables, adverse events, or known reasons for discontinuation. The utility differences were slightly smaller when imputed (Supplement 4).

Figure 2. Scatterplots of bootstrap re-sampling based on actual bed occupancy in 2020 (blue) and capacity-adjusted to an average of 85% bed occupancy (orange) for complete cases (n = 37, boxes a and C) and all cases, using multiple imputation on utility where missing (n = 117, boxes B and D). The horizontal axes show QALY gain with BA versus TAU. The vertical axes show incremental cost in euros (mean cost with BA versus TAU).

Most bootstrap repetitions of the incremental cost-|effectiveness ratios indicated health gains (975–979 out of 1000 among complete cases and 1000 when based on all cases). The difference in QALYs in the BA group versus TAU was statistically significant (t115 = 3·988, p < 0·001, Cohen’s d: 0·738, 95% CI: 0·361–1·111), also when excluding two individuals in the control group who died by suicide during the RCT.

Incremental cost values were both positive and negative, indicating individual-level variation in need for hospital resources, many of which were associated with cost savings. For occupancy rate, among complete cases, 77% of observations indicated cost-savings for the base case (, box A). This figure increased to 87% in the capacity-adjusted scenario (, box C). Ambiguity in costs was more prominent when considering all individuals (, boxes B and D), with 37% of samples indicating cost-savings in the base case and 64% for the capacity-adjusted scenario.

As for decision uncertainty in willingness to pay for a gained QALY, bootstrap scatter plots translated into cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (Supplement 5) illustrate that for complete cases, the probability of BA being cost-effective is high in both scenarios and at all levels of willingness to pay. However, the willingness to pay per QALY gained will affect the probability of BA being cost-effective when considering all cases. For example, with an assumed willingness to pay of 10 000 or 50 000 euros, the probability of BA being cost-effective is 39% or 49% in the base case and 65% or 72% in the capacity-adjusted scenario, respectively.

Long-term follow-up

The average number of admission days and costs per person per year decreased over time for both groups () in the long-term follow-up, including when considering only the 63 participants who completed all six years of the study (Supplement 6). See supplement 7 for costs during follow-up, including costs discounted with 3% to account for differential timing in accordance with recommendations [Citation25]. In the final year of the follow-up, average annual costs were at 25 000 to 26 100 euros among participants, while the costs in the year before the RCT were 70 000 euros. The data indicated a fluctuating need of care over the years, with about half of participants included in the follow-up showing wave-like shifts in admission days (individual patterns are not shown since the approval from the regional ethical review board (2014/570) stated that data should only be presented on a group level).

Figure 3. Number of days admitted to hospital (boxes a and B) and treatment costs in euros (boxes C and D), average per person per year before, during, and after the randomized controlled trial (RCT). BA: intervention group during RCT (n = 56); Control: control group during RCT (n = 61). Base case: prices based on actual bed occupancy rate; Capacity-adjusted scenario: prices based on an average bed occupancy rate of 85%. See supplement 7 for costs during follow-up, including costs discounted with 3% to account for differential timing in accordance with recommendations [Citation25].

![Figure 3. Number of days admitted to hospital (boxes a and B) and treatment costs in euros (boxes C and D), average per person per year before, during, and after the randomized controlled trial (RCT). BA: intervention group during RCT (n = 56); Control: control group during RCT (n = 61). Base case: prices based on actual bed occupancy rate; Capacity-adjusted scenario: prices based on an average bed occupancy rate of 85%. See supplement 7 for costs during follow-up, including costs discounted with 3% to account for differential timing in accordance with recommendations [Citation25].](/cms/asset/40e9cd7f-1f2d-4780-8b07-f105860e0207/ipsc_a_2366854_f0003_c.jpg)

During the RCT, about 80% (46 of 56) of the intervention group participants self-admitted. During follow-up, about two thirds (54 of 81) of participants chose to self-admit to BA at least once, with 58% (47 of 81) self-admitting multiple times, indicating high acceptability of the intervention.

By the end of the follow-up, ten participants had died, including seven by suicide or suspected suicide (). Mean health utility based on WHODAS scores was 0.700 at baseline (n = 101) and 0.772 after five years (n = 58) (Supplement 4 provides more detail on health utility before, during, and after the RCT).

Discussion

The within-trial analysis of cost-effectiveness was sensitive to bed occupancy ranging from 59 000 euros per gained QALY in the base case to cost savings in the capacity-adjusted scenario (85% bed occupancy). All analyses indicated health gains on average due to BA. Inpatient care and related costs showed substantial average reductions in the long-term.

In the present study, access to BA did not lead to increased days in inpatient care [Citation9]. Prior studies on the effects of psychiatric self-admission have indicated both decreased [Citation26,Citation27], unaffected [Citation28], and increased inpatient care and related costs [Citation29]. As BA aims to increase autonomy and self-care, it remains unclear whether an extra inpatient care day due to self-admission is beneficial or harmful, especially in groups who are struggling with help-seeking and stigma [Citation30]. The decrease in inpatient care use and costs over five years with access to BA also resembles the natural course for BPD, whereby only about half of those diagnosed at one point still meet the diagnostic criteria two years later (despite persistent functional impairment) [Citation31].

The results showed economic gains with an 85% bed occupancy both for BA and TAU but a loss when using actual bed occupancy rates for 2020, at 49% and 115% bed occupancy, respectively. Decision-makers may find these results useful for planning the implementation and organization of BA. The lower bed occupancy at the BA unit in 2020 was the result of available premises, staff, and expectations of increased bed occupancy once BA was fully implemented. Bed occupancy may need to be considered in relation to the total number of unit beds, such that two or three BA beds in a mixed unit may require lower occupancy compared to a separate unit with more beds. The latter permits greater occupancy, as the turnover due to maximum admissions of three nights creates flexibility. The work and time devoted to dimensioning BA according to need from initial to full implementation may, from a payer perspective, be seen as part of the resources used to execute an implementation strategy. The psychiatric care unit in this study had 115% bed occupancy in 2020. This overcrowding compared to the goal of 85% occupancy stated in regional activity reports partly explains the cost-effectiveness results of BA in the base case analysis [Citation32]. While it is beyond the scope of this study to analyze the impact of overcrowding on care quality, our analysis clearly shows its impact on cost-estimates.

The ethical platform guiding provision of health care in Sweden states that conditions with high severity should be given priority over less severe conditions. This has been interpreted as a higher willingness to pay for health gains, such as in the reimbursement of medicines, for those with more severe conditions [Citation33]. There is no single cost-effectiveness threshold in Sweden as decisions weigh in severity and other factors. An analysis of decisions regarding reimbursement of pharmaceuticals gives an illustration of how severity matters for approvals [Citation33] (See Supplement 5 illustrating the probability of cost-effectiveness at different levels of willingness to pay per QALY gained). Our study included the most severely ill individuals in the region (including those with >180 admission days in a year). Excluding those with the highest hospital admission rate at baseline increased the cost per QALY gained for BA compared to TAU in our study, which was mainly driven by the lower average cost before the study and the lower savings potential. This suggests that BA should not be limited to those with less prior admission or milder disease.

Given that BA was utilized to varying degrees by the participants, we suggest that future research explore in more detail who is most likely to use and benefit from BA. This would be useful for optimizing the organization of BA.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include that the data were obtained from an RCT using a standardized intervention developed for the target group, the assessment of quality of life, long-term observation, and basing unit costs according to the real-life cost of healthcare. Moreover, we performed subgroup and uncertainty analyses, including varying bed occupancy rates to account for the anticipated uptake of BA. A limitation was that costs related to outpatient care, caregiver burden, or deaths were not included, even though they were expected to be substantial [Citation6]. Other limitations include collection of days in hospital performed by only one investigator, prices based on only one clinic, missing data on birth country and an observed attrition rate of 46% over five years which may impact the generalizability of the results. Conversion of WHODAS answers into QALYs was based on a country-independent mapping function since there was no function available for Sweden. Conversion of WHODAS into QALY yielded similar results when using the only mapping function available which was based on a European country (Slovakia, data not shown). In addition, WHODAS, which only assesses the last 30 days, was used to calculate health utility over the last six months, which may not be valid. It is uncertain how this may have affected results, and future studies might consider this aspect.

Conclusion

BA was associated with significant health gains as measured by QALYs, while the impact on costs was sensitive to assumptions of bed occupancy rates and targeting. Including individuals with an extensive history of psychiatric inpatient care (base case) in the BA group implies lower costs per QALY gained compared to the subgroup with milder illness severity. The results suggest that cost-effective provision of BA, in terms of beds and staff devoted to BA, regardless of whether organized separately or mixed with acute care, should be reconsidered regularly, as cost-effectiveness may differ over the course of initial to full implementation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (97.5 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The clinical data supporting the study findings are not publicly available. In the approval from the regional ethical review board (2014/570), it is stated that data should only be presented on a group level as these might contain sensitive information.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rose-Marie Lindkvist

Rose-Marie Lindkvist, PhD, has a background in health economics and public health and experience of qualitative research on brief admission by self-referral for individuals with self-harm.

Katarina Steen Carlsson

Katarina Steen Carlsson, PhD, associate professor in health economics. Research includes real-world data analyses and economic evaluation. Commissioned health economic expert for authorities, organizations and companies.

Daiva Daukantaitė

Daiva Daukantaitė, PhD, is an associate professor of psychology specializing in youth mental health issues. She was primarily responsible for the statistical analysis in the clinical trial on brief admission by self-referral, which forms the basis of this work.

Lena Flyckt

Lena Flyckt, MD, PhD, is a psychiatrist and associate professor. Her main focus in research has been schizophrenia, and self-harm among emotionally instable individuals, hereunder research on brief admission.

Sofie Westling

Sofie Westling, MD, PhD, is associate professor and lecturer, clinical researcher and senior psychiatrist working clinically with self-harm in adult psychiatry. She was the principal investigator for the clinical trial on brief admission by self-referral which this work was based on.

References

- Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, et al. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ. 2002;325(7374):1207–1211. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207.

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):225–236.

- Mendez-Miller M, Naccarato J, Radico JA. Borderline personality disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(2):156–161.

- Castelpietra G, Knudsen AKS, Agardh EE, et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990-2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;16:100341. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100341.

- Dyvesether SM, Hastrup LH, Hawton K, et al. Direct costs of hospital care of self-harm: a national register-based cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145(4):319–331. doi:10.1111/acps.13383.

- Mehlum L. Cost of self-harm to society is high and increasing: a call for evidence-based and systematic treatment approaches. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145(4):317–318. doi:10.1111/acps.13402.

- Haga E, Aas E, Grøholt B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dialectical behaviour therapy vs. enhanced usual care in the treatment of adolescents with self-harm. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12(1):22. doi:10.1186/s13034-018-0227-2.

- Klonsky ED, Victor SE, Saffer BY. Nonsuicidal self-injury: what we know, and what we need to know. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(11):565–568. doi:10.1177/070674371405901101.

- Westling S, Daukantaite D, Liljedahl SI, et al. Effect of brief admission to hospital by self-referral for individuals who self-harm and are at risk of suicide: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e195463. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.5463.

- Monk-Cunliffe J, Borschmann R, Monk A, et al. Crisis interventions for adults with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;9(9):CD009353. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009353.pub3.

- Coyle TN, Shaver JA, Linehan MM. On the potential for iatrogenic effects of psychiatric crisis services: the example of dialectical behavior therapy for adult women with borderline personality disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86(2):116–124. doi:10.1037/ccp0000275.

- Ustun TB, Kostanjesek N, Chatterji S, World Health Organization., et al. Measuring health and disability: manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0). 2010.

- Strand M, Sjöstrand M. Self-admission in psychiatry: the ethics. Bioethics. 2019;33(1):132–137. doi:10.1111/bioe.12501.

- Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 4th ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Liljedahl S, Marjolein H, Daiva D, et al. Brief Admission: manual for training and implementation developed from the Brief Admission Skåne Randomized Controlled Trial (BASRCT). Lund: Vetenskapscentrum för klinisk psykiatri, Region Skåne; 2017.

- Liljedahl SI, Helleman M, Daukantaité D, et al. A standardized crisis management model for self-harming and suicidal individuals with three or more diagnostic criteria of borderline personality disorder: the Brief Admission Skåne randomized controlled trial protocol (BASRCT). BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):220. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1371-6.

- Lokkerbol J, Wijnen BFM, Chatterji S, et al. Mapping of the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 to disability weights using the Multi-Country Survey Study on Health and Responsiveness. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2021;30(3):e1886.

- CORRIGENDUM. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2022;31(4):e1907. doi:10.1002/mpr.1921.

- Roudijk B, Donders ART, Stalmeier PFM. Setting dead at zero: applying scale properties to the QALY model. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(6):627–634. doi:10.1177/0272989X18765184.

- NICE. Chapter 39, Bed occupancy. In: Emergency and acute medical care in over 16s: service delivery and organisation. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2018.

- Midhage R, Hermansson L, Söderberg P, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Swedish self-rated 36-item version of WHODAS 2.0 for use in psychiatric populations - using classical test theory. Nord J Psychiatry. 2021;75(7):494–501. doi:10.1080/08039488.2021.1897162.

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2020.

- Briggs AH, Wonderling DE, Mooney CZ. Pulling cost-effectiveness analysis up by its bootstraps: a non-parametric approach to confidence interval estimation. Health Econ. 1997;6(4):327–340.

- Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338(jun29 1):b2393–b2393. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2393.

- Attema AE, Brouwer WBF, Claxton K. Discounting in Economic Evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(7):745–758. doi:10.1007/s40273-018-0672-z.

- Strand M, Bulik CM, Gustafsson SA, et al. Self-admission in the treatment of eating disorders: an analysis of healthcare resource reallocation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):465. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06478-1.

- Johansson BA, Holmström E, Eberhard S, et al. Introducing brief admissions by self-referral in child and adolescent psychiatry: an observational cohort study in Sweden. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10(8):598–607. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00157-8.

- Sigrunarson V, Moljord IE, Steinsbekk A, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing self-referral to inpatient treatment and treatment as usual in patients with severe mental disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71(2):120–125. doi:10.1080/08039488.2016.1240231.

- Paaske LS, Sopina L, Olsen KR, et al. The impact of patient-controlled hospital admissions among patients with severe mental disorders on health care cost: A nationwide register-based cohort study using quasi-experimental design. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;144:331–337. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.10.032.

- Klein P, Fairweather AK, Lawn S. Structural stigma and its impact on healthcare for borderline personality disorder: a scoping review. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2022;16(1):48. doi:10.1186/s13033-022-00558-3.

- Torgersen S. The nature (and nurture) of personality disorders. Scand J Psychol. 2009;50(6):624–632. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00788.x.

- Teitelbaum A, Lahad A, Calfon N, et al. Overcrowding in Psychiatric Wards is Associated With Increased Risk of Adverse Incidents. Med Care. 2016;54(3):296–302. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000501.

- Svensson M, Nilsson F. [The Swedish dental and pharmaceutical benefits agency’s willingness to pay for new drugs has been analyzed]. Lakartidningen. 2016;113:DX44.