Abstract

Background

Depression in adolescence is a serious major global health problem with increasing rates of prevalence. Measures of depression that are valid for young people are clearly needed in clinical contexts.

Methods

The study included 577 patients from child and adolescent psychiatry (n = 471) and primary care (n = 106) aged 12–22 years in Sweden (Mage=16.7 years; 76% female). The reliability and validity for Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth (MADRS-Y) were investigated. To confirm the latent structure, we used a single-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). A Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to test total score differences between diagnostic groups. Using Spearman’s rho correlations, we examine whether single items in the MADRS-Y correlate with suicidal ideation measured by The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-JR (SIQ-JR).

Results

The internal consistency using McDonald’s coefficient omega was excellent. The CFA of the 12-item MADRS-Y supported a one factor structure. Evidence of convergent and discriminant validity was shown. There was a significant difference in MADRS-Y scores across diagnostic groups, with higher results for depressive disorders. A strong correlation with suicidal ideation was found for two items.

Conclusions

The results support MADRS-Y as a brief, reliable, and valid self-report questionnaire of depressive symptoms for young patients in a clinical setting.

Depression in adolescence is a serious major health concern worldwide [Citation1–3]. With a one-year period prevalence of 8% and lifetime prevalence of 19% in the Western countries, depression is more common in adolescents than in adults [Citation1]. It is well-established that more females than males are affected [Citation2] and a significant increase in depression has been observed specifically among female adolescents over the last decade [Citation3–5]. The high prevalence and increasing rates are concerning because adolescent depression is a significant risk factor for suicide [Citation6–8], substance use disorder [Citation7,Citation9], negative psychosocial outcomes [Citation10], and adult depression [Citation11].

Measures of depression that are valid across different contexts and age groups as well as for research are clearly needed for assessment of symptom severity and treatment effectiveness [Citation12]. Self-report questionnaires for adolescents are a suitable tool for assessing different levels of depression [Citation13] and have been shown to better capture depressive symptoms as compared to clinical interview, both for subthreshold states and for the most serious symptoms [Citation14,Citation15]. Ideally, self-reporting should be used together with clinical interviews in assessment and treatment planning [Citation16,Citation17]. Regular assessment of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation is also important during ongoing treatment [Citation16]. Although adolescent depression symptoms differ from those of adults [Citation18], many depression self-report questionnaires used in adolescent populations have not been sufficiently psychometrically evaluated for this age group [Citation19].

There are several self-report questionnaires for depression available in Swedish. Knowledge Support for Caregivers [Citation20] recommends using the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS) [Citation21], which is not validated in a Swedish context to be used for adolescents, and the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Self report (MADRS-S) [Citation22,Citation23]. Evidence from a previous study of MADRS-S [Citation24] has shown adequate levels of diagnostic accuracy for Swedish adolescents in two child and adolescent outpatient clinics. However, MADRS-S is developed for adults and not adapted for young people.

The self-report questionnaire Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth (MADRS-Y) [Citation25] is an adapted version of MADRS-S with age-appropriate instructions, item descriptions and content, with the aim to capture depressive symptoms in young people. There are three items in MADRS-Y that are not included in MADRS-S: irritability, increased sleep, and increased appetite. MADRS-Y is a brief dimensional self-report questionnaire that relates to all the DSM-5 criteria for adolescent depression, except the psychomotor disturbance criteria [Citation25]. The MADRS-Y has shown to be reliable, and valid for screening of depressive symptoms in a normative sample of Swedish students aged 12–20 years [Citation25], but has not yet been investigated in a clinical setting. In the current study, we included young patients 12–22 years old, capturing an age range from adolescence to young adulthood. Young adults with mental disorders show clinical similarities with adolescents with the same conditions [Citation26].

The aim of this study is to investigate the psychometric properties in terms of validity, reliability, and factor structure of the self-report questionnaire MADRS-Y in a psychiatric sample of young patients aged 12–22 years. We also aim to compare the MADRS-Y total score in this psychiatric sample with a normative non-clinical sample to test the hypothesis that the MADRS-Y total score is higher in the psychiatric sample. Furthermore, we aim to test whether the MADRS-Y total score differs between diagnostic groups, and finally, we examine correlations for each item with suicidal ideation as assessed by the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-JR (SIQ-JR) [Citation27].

Method

Study setting

This study is part of the project Adolescents’ experience of mental illness – psychometric properties of new Swedish versions of tests (UPOP) [Citation28]. The purpose of UPOP is to develop new instruments for screening and evaluation of treatment effects of mental illness among young patients. The current study was conducted in the northern part of Sweden. Data was gathered from 2018 to 2022 in four towns (population range 8,000–133,000: Lycksele 8,000, Örnsköldsvik 55,000, Skellefteå 77,000 and Umeå 133,000) from young patients in four child and adolescent psychiatry clinics, one primary care youth clinic and one primary care health clinic.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Swedish Regional Ethical Review Board (number 2018/59-31).

Young patients with symptoms of anxiety and depression (with concurrent treatment or on a waiting list for treatment) were informed about the study by mail or text message and if they did not respond, they received a phone call from a research assistant. Flyers were also posted in the clinics’ waiting rooms. There were 1,396 individuals initially interested and 582 (42%) of these choose to participate. Due to missing data in five cases (25–60% missing items), there were 577 participants left for analyses.

Participants

The participants were patients aged 12–22 years. Inclusion criteria were: 1) having self-reported or parent-reported symptoms of depression and/or anxiety (all comorbidities were allowed), 2) in the event of recent psychiatric inpatient care or suicide attempt, at least three months had to have passed since discharge from hospitalization or the suicide attempt, and 3) fluency in written Swedish and ability to complete the online questionnaires.

Measures

Description of the self-report questionnaire MADRS-Y

Montgomery–åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth (MADRS-Y)

MADRS-Y is a brief self-report questionnaire including 12 items, tested in a normative sample of adolescents aged 12–20 years [Citation25]. It has been adapted from the adult version, MADRS-S [Citation23], and measures depression symptoms. MADRS-Y has instructions describing that the focus should be on how the respondent is feeling currently and during the last three days. The items include questions about sadness, irritability, anxiety, reduced sleep, increased sleep, reduced appetite, increased appetite, concentration difficulties, lassitude, inability to feel, thoughts about yourself and your future, and suicidal thoughts. The self-report is measured with a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (low) to 6 (high) and the maximum score is 72. The internal consistency has been established in two samples (sample one n = 310, aged 12–20 years, sample two n = 310, aged 12–20 years) and was good (e.g. Cronbach alpha .89 for each sample) [Citation25]. The MADRS-Y is available as supplementary material.

Convergent validity

Montgomery–åsberg Depression Rating Scale – self report (MADRS-S)

MADRS-S is a self-report dimensional questionnaire for adults measuring depressive symptoms [Citation22,Citation23]. The questionnaire has nine items, including questions about mood, feelings of unease, sleep, appetite, ability to concentrate, initiative, emotional involvement, pessimism, and zest for life. MADRS-S is measured with a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (low) to 6 (high) and the maximum score is 54. A higher score indicates more severe depression [Citation22]. MADRS-S is a reliable and valid instrument with good sensitivity for screening MDD in adults. Internal consistency measured with Cronbach’s alpha has shown to be between .76 and .94 for adults (see compilation by Citation24]. One study validated the questionnaire in an adolescent outpatient psychiatric sample [Citation24] and showed that the psychometric properties of the MADRS-S (n = 105, mean age 16 years) were good (e.g. Cronbach alpha .87). Furthermore, ROC analyses supported very good diagnostic accuracy, where AUC was 0.86 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.78–0.93, p < .001) [Citation24]. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .89, 95% CI [.87, .90].

Divergent validity

Patient-Reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS)

The PROMIS project aims to develop, validate, and standardize item banks to measure patient-reported health. It is initiated by the US National Institutes of Health [Citation29]. To investigate divergent validity, we used the following PROMIS item banks [Citation29,Citation30], which are different, but all related to the construct depression: PROMIS® Pediatric Item Bank v2.0 – Peer Relationships (15 items) [Citation31], PROMIS® Pediatric Item Bank v1.0 – Family Relationships – Short Form 8a (8 items) [Citation32,Citation33], and PROMIS® Pediatric Item Bank v1.0 – Physical Activity (10 items) [Citation34–36]. The self-report 5-point scales range from 1 (e.g. ‘never’ or ‘not at all’) to 5 (e.g. ‘always’ or ‘almost always’). Cronbach’s alpha in this sample were .90, 95% CI [.88, .91] for peer relationships, .94, 95% CI [.93, .95] for family relationships and .93, 95% CI [.92, .93] for physical activity.

Measure for suicidal ideation

The suicidal ideation questionnaire-JR (SIQ-JR)

SIQ-JR [Citation27] is a self-report questionnaire developed for adolescents aged 12–15 years. It has 15 items, each addressing a specific suicidal cognition and measured with a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (I never had this thought) to 6 (almost every day), with higher scores indicating greater severity of suicidal ideation [Citation37]. The SIQ-JR has been used to assess suicidal ideation in clinical samples of adolescents 12–18 years old [Citation38–40]. Internal consistency measured with Cronbach’s alpha ranged between .93 and .96 [Citation37]. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .96, 95% CI [.96, .97] for the investigated age group of 12–17 years old.

Statistical analysis

The data was first analyzed with descriptive statistics. For age comparison, the sample was divided into two groups: 12–17 years old and 18–22 years old. We used the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test to analyze differences in sex and age because normal distribution was lacking. Cohen’s guidelines for effect size are: r ≥ .1 a small effect, r ≥ .3 a medium effect, and r ≥ .5 a large effect [Citation41]. To investigate any differences in socioeconomic status, we divided the sample into four groups by the occupation of the first parent/caregiver: 1) Workers (n = 115, 20%), 2) Assistant and intermediate non-manual workers (n = 201, 35%), 3) Professionals, civil servants and executives (n = 147, 26%), and 4) Self-employed (n = 48, 8%); the remaining (n = 66, 11%) were unknown. The non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used to measure the impact of socioeconomic status.

Corrected item-total correlations (rit c) were calculated and a correlation of less than .3 indicates that the item does not correlate well with the overall scale and should therefore be removed [Citation42,Citation43]. Inter-correlations between items were calculated by Spearman’s rho. For interpretation, .00–.10 was considered as negligible correlation, .10–.39 as weak correlation, .40–.69 as moderate correlation, .70–.89 as strong correlation and .90–1.00 as very strong correlation [Citation44].

The reliability of the scale was calculated with McDonald’s coefficient omega [Citation45] and for interpretation, 0.7 was considered acceptable, 0.8 good and 0.9 excellent [Citation46]. To enable comparison of reliability with the previous MADRS-Y study, Cronbach’s alpha was also calculated.

To confirm the latent structure of the MADRS-Y in a clinical sample, we used a single-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The internal consistency was examined using the lavaan package for structural equation modelling version 0.6–3.00 [Citation47]. Goodness of fit indices used were: the Satorra–Bentler Chi square (SB χ2), χ2/df (a good model is ≤ 3) [Citation48], the comparative fit index (CFI; a good model is > .90) [Citation49], the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; a good model is > .90) [Citation49], the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; a good model is <.05 and a reasonable model fit is < .08) [Citation50], and standardized root mean square residual, SRMR, a good model is < .08 [Citation51]. Because we had a non-normal distribution and ordinal scale responses, we used a robust diagonally weighted least squares with scaled-shifted test (DWLSSS) estimator [Citation52].

We calculated evidence of the convergent and divergent validity by using Spearman’s rho correlations between MADRS-Y and the convergent and divergent validity measures. For interpretation, .00–.10 was considered as negligible correlation, .10–.39 as weak correlation, .40–.69 as moderate correlation, .70–.89 as strong correlation and .90–1.00 as very strong correlation [Citation44].

Principal component analyses (PCA) were used to show the relationships between the MADRS-Y scale and the divergent validity scales. A variable correlation plot was calculated [Citation53] and it can be interpreted as follows: positively correlated variables are grouped together, and negatively correlated variables are positioned on opposite sides of the plot origin [Citation54].

A Kruskal–Wallis test was calculated to test whether the MADRS-Y total score differed between diagnostic groups, where diagnosis was registered within the range of 30 days before and after completing the MADRS-Y self-report. The analysis was followed by a comparison between median scores in these groups.

Using the one-sample t-test, the mean of the MADRS-Y total score was compared with means from the previous MADRS-Y study with two normative population samples [Citation25].

Spearman’s rho correlations were used to examine whether single items in the MADRS-Y correlate with suicidal ideation measured by SIQ-JR. Since we used the measure SIQ-JR, intended for younger adolescents, the correlations were calculated in the age group 12–17 years old. Due to weakness in the administration structure for handing out this particular questionnaire, there were 316 participants in this age group with completed SIQ-JRs.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 and R using the lavaan package for structural equation modelling version 0.6–3.00 [Citation47].

Results

Descriptive statistics

The participants were 12–22 years old, the mean age was 16.7 years (SD = 2.6) and 76% were females. N = 471 (82%) patients were recruited from child and adolescent psychiatry clinics, N = 103 (18%) at a primary care youth clinic and N = 3 (1%) at a primary care health clinic. Primary ICD-diagnosis could be detected from the medical records for N = 215 patients. N = 62 (30%, 54 females and 8 males) of these had a depressive disorder.

Descriptive statistics for gender, age and socioeconomic status

A Mann-Whitney U test showed that females had higher depressive symptoms compared to males, with a significant difference in the MADRS-Y total score of females (Mdn = 25, n = 440) and males (Mdn = 11, n = 137), U = 14979.00, z = −8.90, p < .001, r = .37, medium correlation according to Cohen’s guidelines [Citation41].

The sample was divided into two age groups: 12–17 years old and 18–22 years old. The Mann-Whitney U test showed no significant difference in the MADRS-Y total score of 12–17 years old (Mdn = 22, n = 412) and 18–22 years old (Mdn = 21, n = 165), U = 34177.50, z = .10, p = .917, r < .001, very small correlation according to Cohen’s guidelines [Citation41].

To investigate any differences in socioeconomic status, the sample was divided into four different socioeconomic status groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test showed no significant difference in MADRS-Y total score across the different groups χ2 (3, n = 511) = 1.06, p = .787.

Descriptive statistics and corrected item-total correlation of the items

Descriptive statistics of the items were analyzed before calculating PCA and CFA. The items 5 (‘increased sleep’) and 7 (‘increased appetite’) had the lowest mean values (M = 1.30 and .94, respectively), and the items 3 (‘anxiety’) and 9 (‘starting to do things’) the highest (M = 2.80 and 2.83, respectively). The corrected item-total correlation (ritc) was higher than .3 for all items, except item 7 (.28); see .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for the montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth (MADRS-Y) questionnaire.

Correlations between items

Spearman’s rho was used to measure intercorrelations between the MADRS-Y items; see . For most of the items, correlation ranged from .36 to .79. The result for item 5 (‘increased sleep’) and item 7 (‘increased appetite’) were weaker (.18–.35). All correlations were significant at p < .001, except for the correlation between item 6 (‘decreased appetite’) and item 7 (‘increased appetite’) (p < .05).

Table 2. Intercorrelations between montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth (MADRS-Y) items using Spearman’s rho.

Reliability

The internal consistency of MADRS-Y total score measured with McDonald’s coefficient omega was excellent (ω = 0.91). This was also supported by the result of Cronbach’s alpha (α =.90).

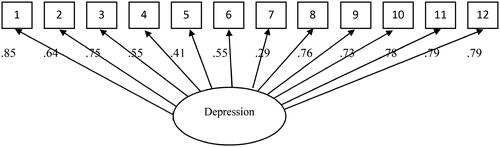

Confirmatory factor analysis

A CFA of the 12-item MADRS-Y supported a one factor structure. The analysis showed a good fit of the model to the data, χ2/df, and RMSEA was better than recommended goodness of fit indices: χ2 (54) = 108.73, χ2/df = 2.01, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = 0.04 (90% CI .03 to .07; SRMR = .05). The scale showed standardized factor loadings higher than .40 for all items except for item 7 (‘increased appetite’); see .

Convergent and divergent validity

Using Spearman’s rho, convergent validity was found with strong correlation between MADRS-Y and MADRS-S (r = .89, p < 0.001). For divergent validity, there were small to moderate associations between the MADRS-Y and the three divergent scales: PROMIS® Pediatric Item Bank v1.0 – Family Relationships – Short Form 8a (r = −0.45, p < 0.001), PROMIS® Pediatric Item Bank v2.0 – Peer Relationships (r = −0.34, p < 0.001) and PROMIS® Pediatric Item Bank v1.0 – Physical Activity (r = −0.13, p < 0.001).

A principal component analysis was conducted to visualize the correlations between the scales; see . This demonstrates that the MADRS-Y scale is very close to MADRS-S, and different from the divergent scales. PROMIS family and peer relationships position themselves on the opposite side of the depression scales. PROMIS physical activity positions itself in a distinct dimension on the PCA.

Figure 2. Principal component analyses of MADRS-Y total scale and all validity measures. Note. MADRS-Y = Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth [Citation58]; MADRS-S = Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Self-rated [Citation52]; PROMIS Family = PROMIS Pediatric Short Form v.1.0—Family relationships 8a [Citation4]; PROMIS Friends = PROMIS Pediatric Bank v2.0 – Peer relationships [Citation17]; PROMIS Physical Activity = PROMIS Pediatric Bank v1.0—Physical activity [Citation55,Citation56].

![Figure 2. Principal component analyses of MADRS-Y total scale and all validity measures. Note. MADRS-Y = Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth [Citation58]; MADRS-S = Montgomery – Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Self-rated [Citation52]; PROMIS Family = PROMIS Pediatric Short Form v.1.0—Family relationships 8a [Citation4]; PROMIS Friends = PROMIS Pediatric Bank v2.0 – Peer relationships [Citation17]; PROMIS Physical Activity = PROMIS Pediatric Bank v1.0—Physical activity [Citation55,Citation56].](/cms/asset/c3a462e5-91a3-46da-b6e5-40caedb09865/ipsc_a_2374417_f0002_c.jpg)

Comparison between different diagnostic groups

A Kruskal–Wallis test revealed a statistically significant difference in MADRS-Y total score across different diagnoses, χ2 (6, n = 214) = 59.78, p < .001. The group with depressive disorders had the highest median (Md = 38), significantly (p < .05) higher than the other diagnostic groups except for the two groups OCD and Other; see .

Table 3. Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – Youth (MADRS-Y) results for different diagnosis groups.

Comparisons with normative samples

The previous MADRS-Y normative study [Citation25] with students 12–20 years old had two samples (N = 310 respectively, with n = 187 females in sample one and n = 196 females in sample two). The mean total score was 11.39 (SD = 10.18) for sample one and 12.33 (SD = 10.66) for sample two. The current sample with a clinical population had significantly higher total scores (M = 22.73, SD = 14.12) than sample one (t(576) = 19.29, p < .001 two tailed) and sample two (t(576) = 17.69, p <.001 two tailed).

Correlation with suicidal ideation

Spearman’s rho showed that all twelve MADRS-Y items separately had a positive correlation (p < .001) with suicidal ideation measured by SIQ-JR total score for 12–17 years old (n = 316). There was a weak correlation for item 5 (‘increased sleep’), r = .30, item 6 (‘reduced appetite’), r = .39, and item 7 (‘increased appetite’), r = .20, a moderate correlation for item 1 (‘sadness’), r = .66, item 2 (‘irritability’), r = .44, item 3 (‘anxiety’), r = .56, item 4 (‘reduced sleep’), r = .41, item 8 (‘concentration difficulties’), r = .51, item 9 (‘lassitude’), r = .47, and item 10 (‘inability to feel’), r = .57, and a strong correlation for item 11 (‘thoughts about yourself and the future’), r = .70 and item 12 (‘suicide thoughts’), r = .82.

Discussion

The present study aimed to test the psychometric properties of the self-report scale MADRS-Y for young patients aged 12–22 years in a clinical setting.

Females rated significantly higher scores in the MADRS-Y than males, which was expected as there was a greater proportion of females with a depressive disorder. There was not a significant difference between the age groups or the socioeconomic status groups.

The corrected item-total correlation (ritc) was higher than .3 for all items, except item 7 (‘increased appetite’) (.28). The same item was also, together with item 5 (‘increased sleep’), weaker in the intercorrelations between the items. A CFA of the 12-item MADRS-Y supported a one factor structure for the Swedish clinical sample, in which all items except item 7 (‘increased appetite’) showed standardized factor loadings higher than .40. In the previous MADRS-Y study with a normative sample, item 7 had the weakest loading of all items in the CFA (.41) and PCA (.42) [Citation25]. Overall, item 7 is the item that shows the weakest association with depression, followed by item 5, which was a weaker result than we expected. The inclusion of item 5 and 7 in MADRS-Y should therefore be questioned. However, at this point, we argue that all items should be included in MADRS-Y to keep the questionnaire consistent with the DSM-5 diagnostic symptom criteria for MDD in younger age groups [Citation55] and for the clinical value. The lower ratings of increased sleep and increased appetite could be because they are more associated with the subtype major depression with atypical features [Citation55], which is important to recognize for appropriate treatment [Citation56]; see previous MADRS-Y study for further discussion in this area [Citation25].

The result of Cronbach’s alpha (α =.90) showing excellent internal consistency was in line with a previous MADRS-Y validation study (α =.89) [Citation25], which strengthens the evidence of reliability.

The presented evidence of convergent and discriminant validity was good, with high correlation between the convergent measure indicating that MADRS-Y is measuring the same construct as MADRS-S. The similarity of the questionnaires may affect the high correlation, however, there are several differences. The two questionnaires include similar items except that the MADRS-Y examines irritability, increased appetite, and increased sleep, which are not included in MADRS-S. The benefits of MADRS-Y are that it is adapted for young people, with easier and modernized language, and that it includes all the DSM-5 criteria for MDD in adolescents except the psychomotor disturbance criteria [Citation55].

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed a statistically significant difference in MADRS-Y total score across different diagnoses, with significantly higher results for depressive disorders than other diagnostic groups, except for the groups OCD and Other. The results indicate an ability to differentiate groups with depression from non-depression groups and may support the use of MADRS-Y in psychiatric settings. Compared with a normative sample, MADRS-Y had a significantly higher result in the clinical sample, indicating an ability to differentiate clinical groups from non-clinical.

All twelve MADRS-Y items separately had a positive correlation (p < .001), with suicidal ideation measured by an SIQ-JR total score for ages 12–17, and a strong correlation was found for item 11 (‘thoughts about yourself and the future’), r = .70, and item 12 (‘suicide thoughts’), r = .82. The strong correlation for item 11 is in line with the suicidality theory of Beck [Citation57], emphasizing that negative expectancies about the future (hopelessness) is a key psychological factor in suicidal behaviors and has a crucial relationship to suicidal intent [Citation57–59]. Items 11and 12 specifically aim to assess suicidal ideation and behaviors, and it needs to be underscored that no instruments have sufficient reliability to predict suicidal acts [Citation60].

Limitations

The distribution of sex was skewed, including more females than males, mirroring the clinical reality [Citation1, Citation4]. However, in the previous MADRS-Y study [Citation25], measurement invariance analysis indicated that the scale performs equally in both sexes.

We did not know how the diagnostic assessment was performed in the clinics, as it was not conducted as a part of the study. Consequently, the results of the diagnostic group analyses should be interpreted with caution. Adding to the uncertainty, only 214 participants had a diagnosis recorded within 30 days before and after completing the MADRS-Y.

Additional investigations of MADRS-Y are warranted, preferably with an interview-based measure as reference test.

Conclusions

MADRS-Y demonstrated good psychometric properties in a Swedish clinical sample of young patients aged 12–22 years, supporting the results from the previous normative study.

The questionnaire is brief and can be used by clinicians to assess depression severity among young patients 12–22 years old in Sweden, and for research purposes.

MADRS Y questionnaire translated into English to reviewers.docx

Download MS Word (32.4 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank all the young people who participated in this project, the clinic staff, and the research assistants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Magnus Vestin is a PhD student at Department of Clinical Science, the Child- and Adolescent Psychiatry unit, Umeå University, Sweden. He is a licensed psychologist, specialist in clinical child and youth psychology, at the Child and adolescent psychiatry clinic in Umeå.

Ida Blomqvist, MD, PhD, is a resident in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry in the region of Västernorrland and a researcher at the department of Clinical Science, the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry unit, Umeå University.

Eva Henje is a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist and professor in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Department of Clinical Science at Umeå University. Her clinical work and research is mainly focused on trauma- and stress related disorder and depression in youth.

Inga Dennhag, docent, psychologist and psychotherapist. She teaches and work with research at the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Umeå University in Sweden. Her main research areas are psychometrics, sexual harassments, teenage depression, and trauma. Year 2017, the book Power and Psychotherapy came out.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.V, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61(2):287–305. doi:10.1111/bjc.12333.

- Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, et al. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056–1067. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60871-4.

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Martinez AM, et al. Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol Med. 2018;48(8):1308–1315. doi:10.1017/s0033291717002781.

- Keyes KM, Platt JM. Annual Research Review: sex, gender, and internalizing conditions among adolescents in the 21st century - trends, causes, consequences. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;65(4):384–407. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13864.

- Twenge JM, Cooper AB, Joiner TE, et al. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(3):185–199. doi:10.1037/abn0000410.

- Brådvik L. Suicide risk and mental disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):2028. doi:10.3390/ijerph15092028.

- Grossberg A, Rice T. Depression and suicidal behavior in adolescents. Med Clin North Am. 2023;107(1):169–182. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2022.04.005.

- Miller L, Campo JV. Depression in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(5):445–449. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2033475.

- O’Neil KA, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in youth: comorbidity, risk, temporal order, and implications for intervention. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(1):104–112. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.002.

- Clayborne ZM, Varin M, Colman I. Systematic review and meta-analysis: adolescent depression and long-term psychosocial outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58(1):72–79. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.896.

- Johnson D, Dupuis G, Piche J, et al. Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: a systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(8):700–716. doi:10.1002/da.22777.

- Ekbäck E, Blomqvist I, Dennhag I, et al. Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale second edition (RADS-2) in a clinical sample. Nord J Psychiatry. 2023;77(4):383–392. doi:10.1080/08039488.2022.2128409.

- Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(8):783–822. doi:10.1037/bul0000102.

- Joiner TE, Jr., Walker RL, Pettit JW, et al. Evidence-based assessment of depression in adults. Psychol Assess. 2005;17(3):267–277. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.17.3.267.

- Karsten J, Nolen WA, Penninx BW, et al. Subthreshold anxiety better defined by symptom self-report than by diagnostic interview. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1-3):236–243. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.006.

- Choe CJ, Emslie GJ, Mayes TL. Depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2012;21(4):807–829. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2012.07.002.

- Jeffrey J, Klomhaus A, Enenbach M, et al. Self-report rating scales to guide measurement-based care in child and adolescent psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2020;29(4):601–629. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2020.06.002.

- Rice F, Riglin L, Lomax T, et al. Adolescent and adult differences in major depression symptom profiles. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:175–181. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.015.

- Stockings E, Degenhardt L, Lee YY, et al. Symptom screening scales for detecting major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:447–463. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.061.

- Knowledge Support for Caregivers. Depression och nedstämdhet hos barn och unga 6-17 år; 2021. https://kunskapsstodforvardgivare.se/omraden/psykisk-halsa/vagledningsdokument-for-barn-och-unga-med-psykisk-ohalsa/depression-och-nedstamdhet-hos-barn-och-unga-6-17-ar.

- Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, et al. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38(8):835–855. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00130-8.

- Svanborg P, Asberg M. A comparison between the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the self-rating version of the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). J Affect Disord. 2001;64(2-3):203–216. doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00242-1.

- Svanborg P, Asberg M. A new self-rating scale for depression and anxiety states based on the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89(1):21–28. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01480.x.

- Ntini I, Vadlin S, Olofsdotter S, et al. The Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Rating Scale - self-assessment for use in adolescents: an evaluation of psychometric and diagnostic accuracy. Nord J Psychiatry. 2020;74(6):415–422. doi:10.1080/08039488.2020.1733077.

- Vestin M, Åsberg M, Wiberg M, et al. Psychometric validity of the Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Rating Scale for Youths (MADRS-Y). Nord J Psychiatry. 2022;77(5):421–431. doi:10.1080/08039488.2022.2135761.

- Chanen AM, Betts JK, Jackson H, et al. A Comparison of Adolescent versus Young Adult Outpatients with First-Presentation Borderline Personality Disorder: findings from the MOBY Randomized Controlled Trial. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67(1):26–38. doi:10.1177/0706743721992677.

- Reynolds WM. Suicidal ideation questionnaire- junior. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987.

- Dennhag I. Ungdomar med psykisk ohälsa: nya psykometriska test (UPOP). 2018. https://www.umu.se/forskning/projekt/ungdomar-med-psykisk-ohalsa-nya-psykometriska-test-upop/.

- Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–s11. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55.

- HealthMeasures. Publication Checklist; 2021. https://www.healthmeasures.net/resource-center/research-tools/publication-checklist.

- Dewalt DA, Thissen D, Stucky BD, et al. PROMIS Pediatric Peer Relationships Scale: development of a peer relationships item bank as part of social health measurement. Health Psychol. 2013;32(10):1093–1103. doi:10.1037/a0032670.

- Bevans KB, Riley AW, Landgraf JM, et al. Children’s family experiences: development of the PROMIS(®) pediatric family relationships measures. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(11):3011–3023. doi:10.1007/s11136-017-1629-y.

- Cox ED, Connolly JR, Palta M, et al. Reliability and validity of PROMIS® pediatric family relationships short form in children 8-17 years of age with chronic disease. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(1):191–199. doi:10.1007/s11136-019-02266-x.

- Carlberg Rindestig F, Wiberg M, Chaplin JE, et al. Psychometrics of three Swedish physical pediatric item banks from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)®: pain interference, fatigue, and physical activity. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5(1):105. doi:10.1186/s41687-021-00382-2.

- Tucker CA, Bevans KB, Teneralli RE, et al. Self-reported pediatric measures of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and strength impact for PROMIS: conceptual framework. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2014;26(4):376–384. doi:10.1097/pep.0000000000000073.

- Tucker CA, Bevans KB, Teneralli RE, et al. Self-reported pediatric measures of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and strength impact for PROMIS: item development. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2014;26(4):385–392. doi:10.1097/pep.0000000000000074.

- Reynolds WM, Mazza JJ. Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: reliability and validity of the suicidal ideation questionnaire-JR. School Psych Rev. 1999;28(1):17–30. doi:10.1080/02796015.1999.12085945.

- King CA, Jiang Q, Czyz EK, et al. Suicidal ideation of psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents has one-year predictive validity for suicide attempts in girls only. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(3):467–477. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9794-0.

- King CA, O’Mara RM, Hayward CN, et al. Adolescent suicide risk screening in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(11):1234–1241. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00500.x.

- Maultsby K, López R, Jr., Wolff J, et al. Longitudinal relations between parenting practices and adolescent suicidal ideation in a high-risk clinical sample: a moderated mediation model. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2023;51(5):613–623. doi:10.1007/s10802-022-01018-9.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

- Everitt BS. The Cambridge dictionary of statistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP; 2002.

- Field AP. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. 5th ed. London: Sage Publications; 2018.

- Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(5):1763–1768. doi:10.1213/ane.0000000000002864.

- Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol. 2014;105(3):399–412. doi:10.1111/bjop.12046.

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994.

- Rosseel Y. lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Soft. 2012;48(2):1–36. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 1998.

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with eqs and eqs/windows: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. doi:10.1177/014662169401800208.

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol Methods Res. 1992;21(2):230–258. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005.

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

- Li CH. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods. 2016;48(3):936–949. doi:10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7.

- Abdi H, Williams LJ. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Computational Statistics. 2010;2(4):433–459. doi:10.1002/wics.101

- Kassambara A. Practical guide to principal component methods in R. Vol. 2. South Carolina: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform; 2017.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Virginia: APA; 2013.

- Singh T, Williams K. Atypical depression. Psychiatry. 2006;3(4):33–39.

- Beck AT. Hopelessness as a predictor of eventual suicide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;487(1):90–96. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb27888.x.

- Bedrosian RC, Beck AT. Cognitive aspects of suicidal behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1979;9(2):87–96. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1979.tb00433.x.

- Wenzel A, Beck AT. A cognitive model of suicidal behavior: theory and treatment. Appl Prev Psychol. 2008;12(4):189–201. doi:10.1016/j.appsy.2008.05.001.

- SBU. Instrument för bedömning av suicidrisk. En Systematisk Litteraturöversikt (Vol SBU-rapport nr 242). 2015.