ABSTRACT

Introduction

This paper describes the concept and content of early adolescents’ emotional skills among the general population. The research literature contains many emotional skills-related terms with overlapping meanings, and it can be challenging to determine which are applicable for example, to a music therapy assessment tool. This study comprises the first phase of developing an assessment tool for early adolescents’ emotional skills, namely, determining what is to be assessed.

Method

A scoping review of the literature is presented with written definitions of emotional skills-related terms, as well as a concept analysis of the terms performed using Walker and Avant’s method.

Results

The components of early adolescents’ emotional skills are presented. Early adolescents’ emotional skills comprise several skill components as presented in the current research literature. These components help in understanding the multifaceted entirety of emotional skills.

Discussion

This paper presents the term emotional skills as a practical, general term that includes the content of other emotional skills-related terms. The concept analysis’ outcome, the components of early adolescents’ emotional skills, is applicable to future research as a theoretical framework for developing an assessment tool for early adolescents’ emotional skills. The components are also useful for music therapy clinicians to analyse their work with early adolescents and to communicate in detail the phenomenona related to emotional skills in therapy.

Introduction

A lack of interaction and emotional skills is often a part of mental and social problems for early adolescents (Gonçalves et al., Citation2019; Parker et al., Citation2006; Zins & Elias, Citation2006). These problems are also related to challenges in school and use of intoxicants (Zins & Elias, Citation2006). A lack of emotional skills is also a recognised issue in clinical music therapy practice with early adolescents (Lindahl Jacobsen, Citation2019). In Finland, early adolescents (10–14 years) account for 60% of all children (0–15 years) in music therapy rehabilitation. Eighty-five percent of these early adolescents have mental or behavioural problems (Social Insurance Institution of Finland, Citation2017). These various angles indicate the justifiable reasons to focus research to develop music therapy assessment on this age group and their needs.

In this research, the term “emotional skills” is chosen as a general term that covers at least somewhat other emotional skills-related terms. In Finland, the term “emotional skills” is in daily use by rehabilitation professionals and is typically used in official rehabilitation reports and documents. The term “emotional skills” is commonly used in everyday language, but many other terms are also used in a research context. The terms are often overlapping, and finding a practical theory-based definition that is applicable for helping to structure a music therapy assessment tool, for example, may be challenging. Inconsistencies in the use of these terms dictate the need for further exploration to develop clear definitions that fulfil scientific requirements (Humphrey et al., Citation2007; Matthews et al., Citation2002; Wigelsworth et al., Citation2010).

Systematic research-based theory building of music therapy assessment tools is increasing but still scarce in music therapy research generally (Cripps et al., Citation2016; Waldon & Gattino, Citation2018; Wheeler, Citation2018). Before developing and validating an assessment tool, the phenomenon should be well grounded in theories and clearly defined (DeVellis, Citation2017). This article presents one possible way to define a concept and start building a theoretical framework for a music therapy assessment tool for early adolescents’ emotional skills.

Early adolescence

Early adolescence is the first step in a transition period when childhood is left behind for the biological, cognitive, and socio-emotional changes one goes through to reach adulthood. Early adolescence begins at approximately 10 to 13 years of age (Santrock, Citation2008) but is usually considered as the period between 11 and 13 years of age (Levesque, Citation2012; Salmela-Aro, Citation2011). Changes in one’s body and strengthening sexual awareness challenge the balance established in childhood (Impiö, Citation2005). Changes also happen on a neurobiological level, which are part of the cognitive and affective behaviour seen during early adolescence (Yurgelun-Todd, Citation2007).

Typical for early adolescents are, for example, a struggle with emotional and social development, feeling awkward about oneself and one’s own body image, worrying about being normal, having heightened conflicts with parents, becoming increasingly influenced by peer groups, having an increased desire for independence, returning to childish behaviour when stressed, being prone to mood swings, testing rules and limits, becoming more private, and having a growing interest in sex (Sawyer et al., Citation2012).

In Piaget’s cognitive development theory early adolescence is called the formal operational period. Children begin to use logic to solve abstract problems and can develop a hypothesis, plan how to test the hypthothesis, and also consider possible cosequences of different hypotheses. At the end of this period, early adolescents can perform relativistic thinking and are able to consider their own behaviour (Carr, Citation2016). Bandura (Citation2018) describes these aforementioned skills in his social cognitive theory using three main properties. These are forethought, in which people can motivate and guide themselves by action plans, goals, and visualizing the outcomes; self-reactiviness, which means people’s ability to perform self-regulation, and self-reflectiveness, with which people can self-examine their functioning (Bandura, Citation2018).

Emotional skills of early adolescents

Brummer (Citation2005) pointed out that the normal emotional development of early adolescence is based on the developmental periods of earlier childhood. Unfinished childhood psychological development can cause difficulties for early adolescents when moving between life phases; one’s biological and psychological age may collide with each other. Carr (Citation2016) emphasized how attachment relationships with parents or caregivers are the foundation for the rules of recognizing, understanding, and managing emotions and also interactions with peers and others through modelling and reinforcement. In early adolescence, children increase the use of multiple startegies for regulating emotions and managing stress. They differentiate between emotional expression with close friends and others, and they better understand social roles and how to regulate emotions in making and maintaining friendships (Carr, Citation2016).

A successful transition from middle childhood (period between 6 and 12 years) to early adolescence requires a successful latency stage. Latency occurs in middle childhood and is marked by increased numbers of relationships with peers and adults outside the family, ego function growth (the ego is the personality component that deals with the external world and its practical demands; American Psychological Association, Citation2018), skills, activities, and interests and by adaptation to the rules of the family and community (Furman, Citation1991).

A crucial developmental task during the latency stage is strengthening the self. The “self” is based on the theory of psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut and relates to the individual’s intrapsychic sturctures that can reliably regulate and calm the person (Baker & Baker, Citation1987). The essential quality of having a strong sense of self is the ability to internalise contradictions. In practice, this means that children with a strong enough self do not need to display their own internal conflicts as aggressive behaviour towards other people because they are able to internally process such conflicts. (Brummer, Citation2005).

An emotional life develops forward when regulatory abilities and emotional experiences are more internalised (Henderson et al., Citation2017). A sufficiently strong self is flexible, permissive, and empathic; can tolerate anxiety, fear, shame, guilt, and conflicts, and is also capable of protecting oneself from those emotions. Furthermore, a strong enough self is capable of playfulness. When the latency stage is closed, the childhood’s dependency and needs are no longer a goal, and the child wants to grow up and change (Brummer, Citation2005).

Emotional skills of early adolescents in music therapy

Music therapy is a therapeutic approach used with early adolescents who have emotional difficulties. Often, these early adolescents come to music therapy because of behavioural problems and an inability to regulate their feelings. They can be either aggressive or withdrawn. Other reasons can include, for example, a challenging life situation, fears, difficulty concentrating, low self-esteem, or obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Music therapy offers the possibility to process emotions in a nonverbal way and therefore is suitable for clients who need a more practical approach to working with emotions (Finnish Society for Music Therapy, Citation2015).

Previous research has supported the use of music therapy with emotionally disturbed early adolescents (Gold et al., Citation2004, Citation2007). However, studies with larger sample sizes and higher methodological quality performed in various research settings are still needed (Geipel et al., Citation2018; Porter et al., Citation2017). Based on research, music therapy for early adolescents with emotional challenges may reduce anxiety (Hendricks et al., Citation1999), have an influence on mood state (Shuman et al., Citation2016), increase emotional responsiveness (Wasserman, Citation1972), reduce impulsiveness and increase self-regulation (Layman et al., Citation2002; Uhlig et al., Citation2018), and help the adolescents to develop a self-image (Friedlander, Citation1994).

Both music and emotions are multilevel constructs that are influenced by multiple variables, processes, and interactions. The literature has examined the role of music-induced emotions in culture, music’s ability to facilitate group emotions, the musical properties that contribute to emotional responses and the communicative function of music-induced emotions. However, studies are still needed to help understand the complexity of the interactions between music and emotions and how this knowledge can be used in an intentional way in music therapy among early adolecents for example (Moore, Citation2017).

Emotional skills of early adolescents in music therapy assessment

Music therapy assessment tools that are probably applicable to early adolescents’ emotional skills have been developed for different purposes, settings, and contexts. However, most of these tools target both children and adolescents, such as Baxter et al. (Citation2007), Carpente (Citation2013), Langan (Citation2009), MacKeith (Citation2011), Layman et al. (Citation2002), Douglass (Citation2006), and Goodman (Citation1989), or are applicable to all age groups, such as Loewy (Citation2000). Based on Cripps et al.’s (Citation2016) comprehensive overview of outcome measures in music therapy, the only assessment tool that was strictly limited to early adolescence was Wells (Citation1988) Music Therapy Assessment for Disturbed Adolescents. Remarkably, none of these tools has been validated among early adolecents.

Additionally, none of these aforementioned assessment tools focuses comprehensively on emotional skills; mainly they highlight some particular aspect of emotional skills instead such as emotional differentiation, expression, regulation, and self-awareness (Baxter et al., Citation2007) or attention, affect, adaption engagement, and interrelatedness (Carpente, Citation2013). They also evaluate emotional expression (Langan, Citation2009; MacKeith, Citation2011), emotional responsiveness (Layman et al., Citation2002) and emotional constriction (Wells, Citation1988). Other tools assess social-emotional functioning or behaviour (Douglass, Citation2006; Goodman, Citation1989) and range of affect (Loewy, Citation2000).

All of these assessment tools are important steps in music therapy assessment research; however, more detailed and focused music therapy assessment tools are still needed specifically for the early adolescent target group and to cover all components of emotional skills.

Study objectives

The purpose of this study is to determine the concept of early adolescents’ emotional skills based on a scoping review and concept analysis of the research literature. Through these methods, the study presents the first phase of the assessment-development process: to describe clearly what is intended to be assessed (DeVellis, Citation2017). We aim to answer the following questions: What are the definitions and theoretical frames of the emotional skills-related terms in the current research literature? What kind of practical general definition of the concept could be applicable as a theoretical framework for developing a music therapy assessment tool for early adolescents’ emotional skills?

Method

Scoping review

We chose to conduct a qualitative scoping review in order to create a foundation for the concept analysis of emotional skills. A scoping review addresses an exploratory research question, and its aim is to map the literature and to identify the key conceps, gaps in the research, types of evidence, and sources available to inform practice and research by systematically searching for, selecting, and synthesizing existing knowledge (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Colquhoun et al., Citation2014; Daudt et al., Citation2013). A scoping review is an appropriate approach for finding papers with diverse methodologies and evidence; for example, it is useful for answering the question “What is known about the concept?” (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) five-step guidelines for conducting a scoping review were used: (a) identify the research question; (b) identify relevant studies; (c) define a relevant study selection; (d) chart the data; and (e) collect, summarise, and report the results (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Step 1 in the scoping review focused on the following question: What are the definitions and theoretical frames of emotional skills-related terms? Steps 2 and 3 are reported by adhering to the PRISMA for Scoping Review Checklist (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The PRISMA flow diagram depicts the flow of information through the different phases of a scoping review (see ). It maps out the number of studies identified, included, and excluded and the reasons for the exclusions (PRISMA, Citation2015). Step 4 and 5 are presented in the table of study characteristics (see ).

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies

Preparation phase of the scoping review

The main search was prepared and relevant keywords were found using the Web of Science and Scopus databases. A professional information specialist searched the databases by focusing on early adolescents and emotional skills. This preparation phase determined the main search strategy. In the preparatory phase, the concept of emotional skills was found not to be solid, and the databases offered many related concepts for the search. Fourteen other terms in addition to the term “emotional skills” were identified as keywords and therefore were relevant search words for this study. The terms were “emotional clarity,” “emotional competence,” “emotional control,” “emotional differentiation,” “emotional functioning,” “social-emotional functioning,” “emotional intelligence,” “emotional learning,” “social-emotional learning,” “emotional maturity,” “emotional regulation,” “emotional responses,” “emotional self-efficacy,” and “emotional states.”

Search strategy for the research articles

The main electronic literature search highlighting these 15 emotional skills-related keywords was performed using the PsycINFO database. PsycINFO was chosen because it covers all of the scientific fields found to be relevant for the topic in the Web of Science and Scopus databases. The timeframe limit of the search was set to end of December 2018. The data search was conducted on 18 April 2019. The search covered all branches of science in PsycINFO and peer-reviewed journals in the English language, and the population was limited strictly to 11- to 13 -year-old early adolescents. The search was done at a title and abstract level, in accordance with PRISMA study selection procedures (Moher et al., Citation2009). A total of 2,206 studies were identified and considered for this qualitative synthesis and concept analysis. The search strategy is listed in .

Table 2. Search strategy from the electronic database

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The papers that were included in the qualitative synthesis met the following criteria: written in the English language, included a written definition of the emotional skills-related terms needed in this study, and possessed a sample group including only 11- to 13-year-olds without a diagnosis or disability. This study focused primarily on the middle period of early adolescence; therefore, 10-year-olds and 14-year-olds were excluded. Usually, early adolescence is considered as the period between 11 and 13 years of age (Levesque, Citation2012; Salmela-Aro, Citation2011).

Populations with special characteristics were excluded because this study focuses on the definition of emotional skills of early adolescents in the general population, to determine which emotional skills are typical for early adolescents. In the assessment-development process, this is based on the assumption that typical development of emotional skills in early adolescents must be defined before one can determine atypical development.

If the study mentioned only the class grade of the participants, the participants’ age was determined by finding the typical age of students in that class grade for that country. Studies that looked at emotional skills-related terms without mentioning any age group or without applicable written definitions of the emotional skills-related term were excluded.

Study selection

All titles and abstracts were initially examined according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria stated above. Six hundred and forty-one full-text articles were reviewed, of which 618 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was an unsuitable age group or a special group with a diagnosis. Two additional studies were identified by scanning the reference lists of the included papers. All of the selected papers (n = 25) were examined independently by a second reviewer to reduce selection bias. There was full agreement between the two reviewers. A total of 25 papers were included in the qualitative synthesis. A detailed overview of the study selection is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram in .

Charting the data

Information on the authors, the publication year, the title of the article, and the sample size were extracted and are presented in . The definitions of emotional skills-related terms and their theoretical background were also explored. Information regarding data collection and design of each study was excluded, though such information is usually considered essential in a scoping review. For the aims of our study, data collection strategy and study design were not relevant as our focus was not on each study’s research details and results per se but how the investigators described the emotional skills-related terms.

Concept analysis

A concept analysis of emotional skills–related terms was performed using Walker and Avant (Citation2014) concept analysis method to explore the features and qualities of the concept and systematically outline the basic elements of the concept and phenomenon. Concept analysis captures the critical elements of the concept at the specific moment in time (Walker & Avant, Citation2014).

The whole qualitative concept analysis procedure includes eight steps, but for the purposes of this study, only the first four steps were applied. The remaining steps focus on semantics and detailed practical examples and were not appropriate or related to the aims of this study. The applied steps of Walker and Avant (Citation2014) concept-analysis method are as follows: (a) select a concept, (b) determine the aims or purposes of the analysis, (c) identify all uses of the concept, and (d) determine the defining attributes.

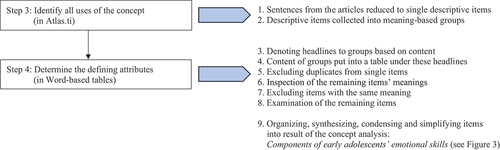

In this study, (a) the concept is emotional skills of early adolescents, and (b) the purpose of the concept analysis was to explore how current research literature defines the emotional skills of early adolescents. The process of applying Steps 3 and 4 of the concept analysis is described in .

Step 3, identification of all uses of the concept, was conducted based on the scoping review data on the terms’ descriptions. The written description of each term was reduced to single items, and items with the same or very similar meanings were then organised into network table groups in Atlas.ti (Version 8.4.5; Atlas.ti, Citation2019) . Atlas.ti is a qualitative data analysis and research software program that enables the researcher to structure text according to thematic content, for example. This phase showed how single descriptors formed groups and were relevant to show different fields of emotional skills.

Step 4, determination of the defining attributes was conducted by collecting the items from these Atlas.ti network table groups, and then tabulating and categorizing them according to their descriptive main headings. The headings were the preexisting words in the table groups and were chosen based on how well they represented the meanings of all of the words in the same group. Repeated items and those with similar meanings were removed. For example, concepts related to regulation were described in the literature as the ability to control positive/negative emotions or ability to manage negative/positive emotions; the meaning of these descriptions are quite similar, and both are under the heading Regulating. The remaining data were synthesized, condensed, simplified, and developed further for the components of early adolescents’ emotional skills resulting from this concept analysis ().

Results

Scoping review

provides a thorough overview of the included studies. A total of 2,206 studies were identified and considered for the qualitative synthesis and the concept analysis. After ineligible studies were excluded for not fulfilling the inclusion criteria 641 full-text articles were reviewed, and 25 papers were included (see ). The sample sizes ranged from one school class (the number of students was not mentioned) to 3,306 early adolescents. The total of n was 11,779 early adolescents. The percentage of females ranged from 41% to 63%; three studies did not mention the gender distribution. Nine terms in the context of early adolescence could be explored from the 15 extracted keyword terms found in the preparation phase from PsychINFO. The papers were published between the years 2004 to 2018. The bulk of the papers were from the field of psychology. The terms and topics of the articles varied greatly across the 25 studies. In the analysed studies, the target group was defined with the following words: “early adolescents,” “youth,” “preadolescents,” “children,” “students,” “pupils,” “young adolescence,” and “young persons.”

Nine of the 15 emotional skills-related key terms were included in the study. These terms were “emotional clarity,” “emotional control,” “emotional functioning,” “emotional intelligence,” “emotional learning,” “social-emotional learning,” “emotional regulation,” “emotional self-efficacy,” and” emotional skills.” The remaining terms were omitted because there were no articles based on the context of early adolesecents. These omitted terms were “emotional competence,” “emotional differentiation,” “social-emotional functioning,” “emotional maturity,” “emotional responses,” and “emotional states.”

All of the included studies had a written description of the emotional skills-related term, and all of the studies identified the theoretical background of the terms’ descriptions. The theories were based on articles published between the years 1986 and 2016 (). The terms “Emotional intelligence,” “social-emotional learning,” and “emotional regulation” were those with the broadest theoretical backgounds. Bandura (Citation1997), Bar-On and Parker (Citation2000), Conway et al. (Citation2016), and Salovey and Mayer (Citation1990) provided the background theory behind more than one of the emotional skills-related terms.

Concept analysis

The outcomes of the concept analysis for the nine emotional skills–related key terms resulted in 91 descriptions of the content of emotional skills when divided into single items. Some items were identical to each other, many of them had the same meaning, and different terms were often used to describe similar attributes. All of the items and their meanings were inspected, collected into groups and tabulated under the relevant headings, synthesized, condensed, simplified and developed further, and placed into a figure describing the components of emotional skills in early adolescents’ lives (see ). The figure represents the implementation of the third and fourth steps of Walker and Avant (Citation2014) concept analysis: identify all uses of the concept that can be discovered and determine the defining attributes.

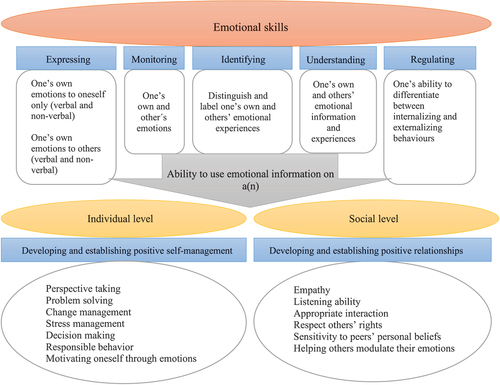

Based on the concept analysis, the main components of early adolescents’ emotional skills are (a) expressing, (b) monitoring, (c) identifying, (d) understanding, and (e) regulating emotions; along with the (f) ability to use emotional information. The last component can be seen as an implication of the five previous components. It comprises two parts: (a) the ability to use emotional information on an individual level for developing and establishing positive self-management and (b) the ability to use emotional information on a social level for developing and establishing positive relationships.

The main components include the person’s own and an interactional point of view as well as positive and negative emotions. The 'expressing' component was divided into nonverbal and verbal expressing and whether the emotions are expressed to oneself only (for example, by writing, painting, by inner voice or crying) or to others. The 'monitoring' component was divided into ability to monitor both one´s own inner emotions as well as other’s emotions. The 'identifying' component involves bringing out one’s ability to distinguish and label emotional experiences. The 'understanding' component accounts for one’s ability to understand both emotional information and experiences. The 'regulating' component includes one’s ability to differentiate between internalizing and externalizing behaviours.

Based on these data, Component 6–'ability to use emotional information on a social and individual level' – includes several subcomponents (see ). The ability to use emotional information on an individual level for developing and establishing positive self-management includes the following skills: perspective taking, problem solving, change management, stress management, decision making, responsible behaviour, and motivating oneself through emotions.

The ability to use emotional information on a social level for developing and establishing positive relationships includes the following skills: empathy, listening ability, appropriate interaction, respecting others’ rights, sensitivity to peers’ personal beliefs, and helping others modulate their emotions.

Discussion

Definition of emotional skills among early adolescents

This study has refined the key concepts related to emotional skills identified in the literature for early adolescents among the general population. The aim was to find a practical, general description that would be applicable as a theoretical framework for developing a music therapy assessment tool for early adolescents’ emotional skills in the future. To do this, a scoping review and a concept analysis of the emotional skills-related terms was conducted. As a result, this study shows that the components of emotional skills include six main skills, which take different sides of emotional skills into account, highlighting the importance of individual- and social-level emotional skills (see ).

Based on this research the main emotional skills are (a) expressing, (b) monitoring, (c) identifying, (d) understanding, (e) regulating; along with the (f) ability to use emotional information on a social level for developing and establishing positive relationships and on an individual level for developing and establishing positive self-management. The five aforementioned skills are considered basic skills, whereas the skill 'ability to use emotional information on the individual and social levels' is more of an implication of these basic skills. It includes several sub-domains that present the diversity of the needed skills, in both positive relationships and self-management. These basic skills and their implication present the general description of emotional skills among early adolescents in the research literature until 2018.

Emotional skills are not disclosed in a particular linear order in because the scoping review articles did not mention the skills’ developmental order. Our impression is that many emotional skills are present simultaneously and often cannot be divided into separate divisions in practical daily life situations or in a research study. Their nature is very dynamic, and their manifestation differs between each developmental stages of the lifespan. Emotional skills also comprise the multiple simultaneous processes in a body and mind based on their neurobiological, neurophysiological, and neuropsychological functions. An individual’s temperament and personality, early interaction and attachment, language development, and cultural context also play roles in the gestalt (e.g. Freund et al., Citation2010; Lamb & Lerner, Citation2015; Plutchik & Kellerman, Citation1983).

However, the presented components of emotional skills in this study (expressing, monitoring, identifying, understanding, regulating, ability to use emotional information on an individual level for developing and establishing positive self-management, and a social level for developing and establishing positive relationships) are useful for music therapy clinicians to analyze their work with early adolescents and to communicate in detail the phenomenona related to emotional skills in the therapy.

Interchangeable emotional skills-related terms

The Web of Science and Scopus databases highlighted 15 keyword terms used for describing emotional skills. This also shows that the term “emotional skills” is not yet solidly defined in the literature. The situation influenced the scoping review and concept analysis: instead of exploring one term, as usually done in a scoping review, it was necessary to focus on many key terms at the same time to explore the gestalt of early adolescents’ emotional skills.

Most of the studies described the terms with overlapping concepts. This supports the idea that in at least some contexts, it is possible and reasonable to use one general term (“emotional skills”) when trying to get a general picture of the topic and its content. However, more distinctive terms should be used in, for example, research or clinical assessment, because the nuances between concepts may be important in some cases. Based on this study, socioemotional learning and emotional intelligence are the most popular emotional skills-related research areas when it comes to the emotional skills of early adolescents.

The theoretical background of emotional skills-related terms offered in the studies highlighted that this field is quite young, dating between 1986 and 2016. Some theoretical backgrounds in the scoping review studies were from the same researcher but from different years of their theoretical work. Some theoretical studies were used as background theory for more than one emotion skills-related term. This also supports the idea that the terms overlap with each other and that in some contexts, it is reasonable to use general term “emotional skills” (see ).

These results are consistent with previous studies that have identified how different terms for emotional skills are used interchangeably (Wigelsworth et al., Citation2010). However, this is the first study to systematically map out the different terms in use across the literature for this or any other age group, and analyse them in terms of concept meaning; therefore, this study may provide a unique contribution to the field. This study contributes to the continued refinement of terms related to emotional skills and will help to provide more concrete definitions across the literature. One of the benefits of providing and using consistent terminology is that doing so allows therapists and clients to interact more clearly, and it also provides the basis for continuous research to be applied in a meaningful way.

Early adolescents as a target group

The number of studies decreased when the search was limited to the age group of early adolescents between 11 and 13 years of age. This study focused primarily on the middle period of early adolescence, when puberty is likely to be actively ongoing. The age range of this study was strict, but even if the age range were extended to include 10- to 14-year olds, the number of studies would not have increased substantially. This showed that research on early adolescents and emotional skills in the general population is quite scarce. This is an interesting and surprising finding, considering how emotionally unstable and meaningful early adolescence is in people’s lives. In a therapy context, it is also valuable to work with early adolecents and their emotional skills because according to Piaget’s cognitive development theory, in this development stage, children are capable of relativistic thinking and are able to consider their own behaviour more profoundly (Carr, Citation2016).

Focusing on early adolescents as the target group was laborious due the lack of definitions in the databases and vague definitions in research on this age group. The PsycINFO database does not allow a search to be narrowed to participants aged 11 to 13 years old; instead, three different age ranges had to be selected (childhood, school age, and adolescence) to be able to include the age range 11–13. In addition, authors did not clearly state the target group of early adolescents in their titles or abstracts. Instead, they used more general terms, like “youth,” “adolescents,” or “young people.” These terms may include early adolescents but also quite a wide group of older or sometimes younger people. Some papers only mentioned the participants’ school grade. Due to international differences in school systems, the class or grade year is not an exact indicator of a child’s age, which was also problematic at the inclusion/exclusion phase. In addition, the names of schools in different countries can vary (e.g. comprehensive school, grade school, elementary school or primary school). In many cases, detailed information about the age of the target group could only be found by reading the full text. Some articles mentioned only the mean age of their target group, and in the context of early adolescence, this is too general a description and could have led to bias at the data-extraction stage. Stricter definitions of early adolescence and the specific age range are needed, both in databases and by authors writing about this age group.

Comparing existing music therapy assessment tools

In general, existing music therapy assessment tools do not include emotional skills components in their gestalt, and they are not validated, especially for early adolescents (Cripps et al., Citation2016). However, when the results of this study are compared to existing music therapy assessment tools, such as the Individualized Music Therapy Assessment Profile (IMTAP) (Baxter et al., Citation2007), which is a general assessment tool for children and adolescents and includes quite an encompassing emotional domain, the components of early adolescents’ emotional skills presented in this study seem to be partly the same. The IMTAP focuses on emotional differentiation/expression, regulation, and self-awareness (Baxter et al., Citation2007). 'Expressing' and 'regulation' are presented with similar captions as the corresponding components in this study. Based on our impression, the content of the IMTAP category 'self-awareness' seems to combine the elements of the components of 'monitoring', 'identifying' and 'understanding' of this study. The IMTAP category 'differentiaton' (combined with the category expression in the IMTAP) on a practical level, seems to be a skill to first identify and then express the emotions. These skills are combined. In this study the component 'identifying' is its own independent part. Category 6 of this study, 'ability to use emotional information on social and individual levels', is not presented in the IMTAP emotional domain.

Future research

Future research could consider studing the applicability of the components to music therapy assessment research. Once the purpose of an assessment tool has been clearly defined, the next step in the assessment-development process is to generate items for an assessment tool (DeVellis, Citation2017). It would also be important to explore how these skills can be seen in music-related work and expression. Additionally, applicability of the defined emotional skills to groups with special needs must be examined. This scoping review and concept analysis could also be repeated in the future when the volume of emotional skills-related research on early adolescents has increased. It might then be possible to cover the whole conceptual field of emotional skills-related key terms in the analysis. Finally, it would be of potential interest to explore whether the presented emotional skills components are relevant to other age groups.

Limitations

Possible data selection bias may have resulted from the limited number of articles on emotional skills-related terms for the target age group. As a result of the literature search, not all 15 keyword terms could be examined in the context of early adolescents in the general population. Therefore, only nine terms of the 15 originally found terms were examined in the scoping review and concept analysis. This means that the definitions and the presented categories are incomplete and do not cover the whole conceptual field of emotional skills-related terms. However, the results do discuss the current state of the art of the literature on early adolescents’ emotional skills. Further bias may have resulted from the concept analysis’s implementation. The implementation process is always somewhat individual, depending on the topic and the researcher’s choices. However, providing as detailed a description of the analysis process as possible (see ) helps other researchers to follow the process and evaluate the decisions made.

Conclusion

This study gives an overall picture of the emotional skills-related terms and their content in the context of early adolescence literature. This study also shows that in at least some contexts, the term “emotional skills” is possible and reasonable to use as a general term when trying to obtain a general picture of the topic and its content. In addition, the study highlights the small amount of research on emotional skills-related terms for early adolescents. Furthermore, the study shows that scoping reviews and concept analysis are useful research methods with which to explore written definitions of terms when the aim is to apply assessment-development theory and its first phase: to determine clearly what one wants to assess. Additionally, this study offers knowledge about the characteristics and theoretical background of the current research on the emotional skills of early adolescents in the general population. As a result, this study presents the components of early adolescents’ emotional skills that are applicable as a theoretical framework, for example, in developing a music therapy assessment tool for this age group. The components are also useful for music therapy clinicians to analyze their work with early adolescents and to communicate in detail the phenomenona related to emotional skills in the therapy.

Despite the limitations and areas that are important to consider in future research and practice, this study offers an interesting point of view and a general overview of early adolescents’ emotional skills as a gestalt. The study fulfils the main objective and offers definitions of emotional skills among early adolescents that are applicable for research developing music therapy assessments in the future.

Acknowledgements

This study was completed in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maija Salokivi

Maija Salokivi, MA, is a music therapist and a doctorand of University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She has been working several years with children and adolescence with psychiatric and neurological problems. The aim of her PhD dissertation is to develop an assessment instrument for emotional skills of early adolescents in the context of music therapy. Her research interests include assessment, assessment development, emotional skills, children and adolescents.

Sanna Salanterä

Sanna Salanterä, PhD, RN, Professor of Clinical Nursing Science, Vice Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at University of Turku and Nurse Director at Turku University Hospital. She is specialized in clinical nursing science, nursing and patient decision-making, smart technology in nursing, pain nursing, health service research, children´s nursing and empowering patient education. She leads the research programs “Health producing basic care with smart technology” and “Health producing health promotion with smart technology.” Both projects consist of several sub projects.

Esa Ala-Ruona

Esa Ala-Ruona, PhD, is a music therapist and psychotherapist working as a senior researcher at the Music Therapy Clinic for Research and Training, at University of Jyväskylä. His research interests are music therapy assessment and evaluation, and in studying musical interaction and clinical processes in improvisational psychodynamic music therapy, and furthermore the progress and outcomes of rehabilitation of stroke patients in active music therapy. Currently he is the president of the European Music Therapy Confederation. He regularly gives lectures and workshops on music therapy both nationally and internationally.

References

- Studies marked with an asterisk were included in the review.

- American Psychological Association. (2018). Dictionary of Psychology. Ego. American Psychological Association. Retrieved October, 2019 from https://dictionary.apa.org/ego

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Atlas.ti. (2019). ATLAS.ti scientific software development GmbH (Version 8.4.5) [Mac educational license].

- Baker, H. S., & Baker, M. N. (1987). Heinz Kohut’s self psychology: An overview. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(1), 1–9.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Bandura, A. (1999). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Key readings in social psychology. The self in social psychology (pp. 285–298). Psychology Press.

- Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617699280

- Bar-On, R. (1997). The emotional intelligence inventory (EQ-I): Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems.

- Bar-On, R., & Parker, J. (2000). The Bar-On EQ-i: YV: Technical manual. Multi-Health Systems.

- Baxter, H., Berghofer, J., MacEwan, L., Nelson, J., Peters, K., & Roberts, P. (2007). The individualized music therapy assessment profile. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- *Benita, M., Levkovitz, T., & Roth, G. (2017). Integrative emotion regulation predicts adolescents’ prosocial behavior through the mediation of empathy. Learning and Instruction, 50(Aug), 14–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.11.004

- Brackett, M. A., Kremenitzer, J. P., Maurer, M., Carpenter, M., Rivers, S. E., & Elbertson, N. (2011). Creating emotionally literate classrooms: An introduction to the RULER approach to social and emotional learning. National Professional Resource.

- Brummer, K. (2005). Lapsuuden normaali kehitys leikki-iästä nuoruuteen. In M. Brummer & H. Enckell (Eds.), Lasten ja nuorten psykoterapia (pp. 29–43). WSOY.

- Carpente, J. A. (2013). The individual music-centered assessment profile for neurodevelopmental disorders: A clinical manual. Regina Publishers.

- Carr, A. (2016). The handbook of child and adolescent clinical psychology. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315744230

- CASEL. (2013) . 2013 CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs-Preschool and elementary school edition.

- *Chung, S., & Moore Mcbride, A. (2015). Social and emotional learning in middle school curricula: A service learning model based on positive youth development. Children and Youth Services Review, 53(June), 192–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.04.008

- *Coelho, V. A., & Sousa, V. (2017). Comparing two low middle school social and emotional learning program formats: A multilevel effectiveness study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(3), 656–667. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0472-8

- Cole, P. M., Martin, S. E., & Dennis, T. A. (2004). Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development, 75(2), 317–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014, December). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

- Conway, A., Miller, A. L., & Modrek, A. (2016). Testing reciprocal links between trouble getting to sleep and internalizing behavior problems, and bedtime resistance and externalizing behavior problems in toddlers. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48(4), 678–689. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0692-x

- Cripps, C., Tsiris, G., & Spiro, N. (Eds.). (2016). Outcome measures in music therapy: A resource developed by the Nordoff Robbins research team. Nordoff Robbins. https://www.nordoff-robbins.org.uk/research-projects/outcome-measures-in-music-therapy/

- Daudt, H. M., Van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-48

- DeVellis, R. (2017). Scale development-theory and applications (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Douglass, E. T. (2006). The development of a music therapy assessment tool for hospitalized children. Music Therapy Perspectives, 24(2), 73–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/24.2.73

- *Downey, L. A., Johnston, P. J., Hansen, K., Birney, J., & Stough, C. (2010). Investigating the mediating effects of emotional intelligence and coping on problem behaviours in adolescents. Australian Journal of Psychology, 62(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530903312873

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school- based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Murphy, B. C., Guthrie, I. K., Jones, S., Friedman, J., Poulin, R., & Maszk, P. (1997). Contemporaneous and longitudinal prediction of Children’s social functioning from regulation and emotionality. Child Development, 68(4), 642–664. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1132116

- Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Reiser, M., Cumberland, A., Shepard, S. A., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. H., Guthrie, I. K., & Thompson, M. (2004). The relations of effortful control and impulsivity to children’s resiliency and adjustment. Child Development, 75(1), 25–46.

- Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Hayenes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-Stone, M. E., & Shriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- *Ferrando, M., Prieto, M. D., Almeida, L. S., Ferrándiz, C., Bermejo, R., López-Pina, J. A., Hernández, D., Sáinz, M., & Fernández, M.-A. (2011). Trait emotional intelligence and academic performance: Controlling for the effects of IQ, personality, and self-concept. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(2), 150–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282910374707

- Finnish Society for Music Therapy. (2015). Finnish Society for Music Therapy. Retrieved January, 2019, from http://www.musiikkiterapia.net/index.php/38-musiikkiterapia-eriasiakasryhmille/84lastenpsykiatria

- Freund, A. M., Lamb, M. E., & Lerner, R. M. Eds. (2010). The handbook of life-span development, Vol. 2: Social and emotional development. John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved from Psychological Experiments Online Database.

- Friedlander, L. H. (1994). Group music psychotherapy in an inpatient psychiatric setting for children: A developmental approach. Music Therapy Perspectives, 12(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/12.2.92

- Furman, E. (1991). Early latency: Normal and pathological aspects. In S. I. Greenspan & G. H. Pollock (Eds.), The course of life, vol.3: Middle and late childhood, (pp.161–203) Internation Universities Press.

- Geipel, J., Koening, J., Hillecke, T., Resch, F., & Kaess, M. (2018). Music-based interventions to reduce internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 255(1), 647–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.035

- Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2000). Individual differences in emotional experience: Mapping available scales to processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(6), 679–697. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200268004

- Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition & Emotion, 16(4), 495–518. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000374

- Gold, C., Voracek, M., & Wigram, T. (2004). Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(6), 1054–1063. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00298.x

- Gold, C., Wigram, T., & Voracek, M. (2007). Effectiveness of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: A quasi-experimental study. Psychotherapy Research, 17(3), 289–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600607886

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. Bantam Books.

- Goleman, D. (1996). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bloomsbury.

- Gonçalves, S. F., Chaplin, T. M., Turpyn, C. C., Niehaus, C. E., Curby, T. W., Sinha, R., & Ansell, E. B. (2019). Difficulties in emotion regulation predict depressive symptom trajectory from early to middle adolescence. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 50(4), 618–630. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00867-8

- Goodman, K. (1989). Music therapy assessment of emotionally disturbed children. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 16(3), 179–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4556(89)90021-X

- Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 224–237.

- Gross, J. J., & Jazaieri, H. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(4), 387–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614536164

- *Gueldner, B., & Merrell, K. (2011). Evaluation of a social-emotional learning program in conjunction with the exploratory application of performance feedback incorporating motivational interviewing techniques. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 21(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2010.522876

- *Hamilton, J. L., Hamlat, E. J., Stange, J. P., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2014). Pubertal timing and vulnerabilities to depression in early adolescence: Differential pathways to depressive symptoms by sex. Journal of Adolescence, 37(2), 165–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.11.010

- *Hamilton, J. L., Kleiman, E. M., Rubenstein, L. M., Stange, M. F., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2016). Deficits in emotional clarity and vulnerability to peer victimization and internalizing symptoms among early adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(1), 183–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0260-x

- Henderson, H. A., Burrows, C. A., & Usher, L. (2017). Emotional development. In B. Hopkins, E. Geangu, & S. Linkenauger (Eds.), The Cambridge encyclopedia of child development (pp. 424–430). Cambridge University Press.

- Hendricks, C. B., Robinson, B., Bradley, L. J., & Davis, K. (1999). Using music techniques to treat adolescent depression. Journal of Humanistic Education and Development, 38(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-490X.1999.tb00160

- Holsen, I., Smith, B. H., & Frey, K. S. (2008). Outcomes of the social competence program second step in Norwegian elementary schools. School Psychology International, 29(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034307088504

- Humphrey, N., Curran, A., Morris, E., Farrell, P., & Woods, K. (2007). Emotional intelligence and education: A critical review. Educational Psychology, 27(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410601066735

- Impiö, P. (2005). Nuoruusiän kehitys. In M. Brummer & H. Enckell (Eds.), Lasten ja nuorten psykoterapia (pp. 44–67). WSOY.

- *Jordan, J.-A., McRorie, M., & Ewing, C. (2010). Gender differences in the role of emotional intelligence during the primary-secondary school transition. Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties, 15(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13632750903512415

- *Kwon, K., Kupzyk, K., & Bentona, A. (2018). Negative emotionality, emotion regulation, and achievement: Cross-lagged relations and mediation of academic engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 33–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.07.004

- Lamb, M. E., & Lerner, R. M. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Socioemotional processes (Vol. 3, 7th ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Langan, D. (2009). A music therapy assessment tool for special education: Incorporating education outcomes. Australian Journal of Music Therapy, (20), 78–98. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.jyu.fi/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2009-08539-007&login.asp&site=ehostlive

- *Latham, M. D., Cook, N., Simmons, J. G., Byrne, M. L., Kettle, J. W. L., Schwartz, O., Vijayakumar, N., Whittle, S., & Allen, N. B. (2017). Physiological correlates of emotional reactivity and regulation in early adolescents. Biological Psychology, 127, 229–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.07.018

- Layman, D. L., Hussey, D. L., & Laing, S. J. (2002). Music therapy assessment for severely emotionally disturbed children: A pilot study. Journal of Music Therapy, 39(3), 164–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/39.3.164

- Levesque, R. J. R. (2012). Developmental periods. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 687–688). Springer-Verlag New York Inc.

- *Li, Y., Allen, J., & Casillas, A. (2017). Relating psychological and social factors to academic performance: A longitudinal investigation of high-poverty middle school students. Journal of Adolescence, 56(1), 179–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.02.007

- Lindahl Jacobsen, S. (2019). Music therapy with children and adolescents at risk. In S. Lindahl Jacobsen, I. Nygaard, & L. Bonde (Eds.), A combrehensive guide to music therapy (2nd ed., pp. 369–375). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Loewy, J. (2000). Music psychoterapy assessment. Music Therapy Perspectives, 18(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/18.1.47

- Luebbers, S., Downey, L. A., & Stough, C. (2007). The development of an adolescent measure of EI. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(6), 999–1009. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.009

- MacKeith, J. (2011). The development of the outcomes star: A participatory approach to assessment and outcome measurement. Housing, Care and Support, 14(3), 98–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/14608791111199778

- Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2002). Emotional intelligence: Science and myth. MIT Press.

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2000). Models of emotional intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 396–420). Cambridge University Press.

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). Basic Books. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480710387486

- Merrell, K. W., Carrizales, D., Feuerborn, L., Gueldner, B. A., & Tran, O. K. (2007). Strong kids: A social and emotional learning program. Brookes.

- *Modrek, A., & Kuhn, D. (2017). A cognitive cost of the need to achieve? Cognitive Development, 44, 12–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2017.08.003

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moore, K. S. (2017). Understanding the influence of music on emotions: A historical review. Music Therapy Perspectives, 35(2), 131–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miw026

- Parker, J. G., Rubin, K. H., Erath, S. A., Wojslawowicz, J. C., & Buskirk, A. A. (2006). Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method (2nd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 419–493). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Petrides, K. V., Frederickson, N., & Furnham, A. (2004). The role of trait emotional intelligence in academic performance and deviant behavior at school. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 277–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00084-9

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15(6), 425–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/per.416

- Phan, H. P. (2017). *The self-systems: Facilitating personal well-being experiences at school. Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 20(1), 115–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-016-9350-1

- Plutchik, R., & Kellerman, H. (Eds.). (1983). Emotions in early development. Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/C2013-0-11314-1

- *Polan, J. C., Sieving, R. E., & McMorris, B. J. (2013). Are young adolescents’ social and emotional skills protective against involvement in violence and bullying behaviors? Health Promotion Practice, 14(4), 599–606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839912462392

- Porter, S., McConnell, T., McLaughlin, K., Lynn, F., Cardwell, C., Braiden, H., Boylan, J., & Holmes, V. (2017). Music therapy for children and adolescents with behavioural and emotional problems: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(5), 586–594. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12656

- *Qualter, P., Whiteley, H. E., Hutchinson, J. M., & Pope, D. J. (2007). Supporting the development of emotional intelligence competencies to ease the transition from primary to high school. Educational Psychology in Practice, 23(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360601154584

- *Reyers, M. R., Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Elbertson, N. A., & Salovey, P. (2012). The interaction effects of program, training, dosage, and implementation quality on targeted student outcomes for the RULER approach to social and emotional learning. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 82–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087377

- *Rubenstein, L. M., Hamilton, J. L., Stange, J. P., Flynn, M., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2015). The cyclical nature of depressed mood and future risk: Depression, rumination, and deficits in emotional clarity in adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 68–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.015

- *Qualter, P., Pool, L. D., Gardner, K. J., Ashley-Kot, S., Wise, A., & Wols, A. (2015). The emotional self-efficacy scale: Adaptation and validation for young adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 33(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282914550383

- *Renshaw, T. L. (2017). Technical adequacy of the positive experiences at school scale with adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 35(3), 323–335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282915627920

- Rydell, A.M., Berlin, L., & Bohlin, G. (2003). Emotionality, emotion regulation, and adaptation among 5- to 8-year-old children. Emotion, 3(1), 30–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1528–3542.3.1.30

- Salmela-Aro, K. (2011). Stages of adolescence. In B. Bradford Brown & M. J. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 360–368). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373951-3.00043-0

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

- Santrock, J. W. (2008). Adolescence. McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Blakemore, S.-J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A. C., & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

- Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A.,Petticrew, M., … Whitlock, E. (2015, January 2). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ (Online). BMJ Publishing Group. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

- Shuman, J., Kennedy, H., DeWitt, P., Edelblute, A., & Wamboldt, M. (2016). Group music therapy impacts mood states of adolescents in a psychiatric hospital setting. The Arts in Psychoterapy, 49, 50–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.014

- *Stange, J. P., Alloy, L. B., Flynn, M., & Abramson, L. Y. (2013). Negative inferential style, emotional clarity, and life stress: Integrating vulnerabilities to depression in adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(4), 508–518. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.743104

- *Top, N., Liew, J., & Luo, W. (2017). Family and school influences on youths´behavioral and academic outcomes: Cross-level interactions between parental monitoring and character development curriculum. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 178(2), 108–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2017.1279118

- Social Insurance Institution of Finland. (2017). Kelan kuntoutustilasto. Kela. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/234527

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- *Trinidad, D. R., Unger, J. B., Chou, C. P., & Anderson Johnson, C. (2004). The protective association of emotional intelligence with psychosocial smoking risk factors for adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(4), 945–954. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00163-6

- Uhlig, S., Janse, E., & Scherder, E. (2018). “Being a bully isn’t very cool … ”: Rap & sing music therapy for enchanced emotional self-regulation in an adolescent school setting- a randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Music, 2018, 46(4), 568–587. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735617719154

- Waldemar, J. O. C., Rigatti, R., Menezes, C. B., Guimarães, G., Falceto, O., & Heldt, E. (2016). *Impact of a combined mindfulness and social-emotional learning program on fifth graders in a Brazilian public school setting. Psychology and Neuroscience, 9(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pne0000044

- Waldon, E. G., & Gattino, G. (2018). Assessment in music therapy -Introductory considerations. In S. Lindahl Jacobsen, E. G. Waldon, & G. Gattino (Eds.), Music Therapy Assessment (pp. 21–73). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Walker, L. O., & Avant, K. C. (2014). Strategies for theory construction (5th ed.). PEARSON.

- Wasserman, N. M. (1972). Music therapy for the emotionally disturbed in a private hospital. Journal of Music Therapy, 9(2), 99–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/9.2.99

- Wells, N. F. (1988). An individual music therapy assessment procedure for emotionally disturbed young adolescents. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 15(1), 47–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4556(88)90051-2

- Wheeler, B. (2018). Assessment in music therapy –Foreword. In S. Lindahl Jacobsen, E. G. Waldon, & G. Gattino (Eds.), Music therapy assessment (pp. 10–17). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Wigelsworth, M., Humphrey, N., Kalambouka, A., & Lendrum, A. (2010). A review of key issues in the measurement of children’s social and emotional skills. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02667361003768526

- *Wigelsworth, M., Lendrum, A., & Humphrey, N. (2013). Assessing differential effects of implementation quality and risk status in a whole-school social and emotional learning programme: Secondary SEAL. Mental Health and Prevention, 1(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2013.06.001

- Yurgelun-Todd, D. (2007). Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(2), 251–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2007.03.009

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016

- Zins, J. E., & Elias, M. J. (2006). Social and emotional learning. In G. G. Bear & K. M. Minke (Eds.), Children’s needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention (pp. 1–13). National Association of School Psychologists.

- Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Wang, M. P., & Walberg, H. J. (2004). Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? Teachers College Press.