ABSTRACT

Introduction

Despite medical advances, preterm birth and neonatal intensive care (NICU) hospitalization are demanding and pose risks for infants and parents. Various music therapy (MT) models have suggested parental singing to promote healthy bonding and development in premature infants, but evidence on long-term effects is lacking.

Method

We present the theoretical framework and intervention protocol of a resource-oriented MT approach for premature infants and their caregivers used in the international LongSTEP trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03564184). We illustrate how guiding principles manifest in MT sessions, describe frames for phases of intervention, discuss prerequisites and present hypothesized mechanisms of change.

Results

The LongSTEP MT approach is resource-oriented, emphasizes parental voice and parent-infant mutual regulation, builds on family-centered care principles, and is relevant in the NICU and beyond. Essential elements include: observation and dialogue on infant and parent needs; voice as the main musical source, with parental voice as the most prominent; active parental participation; modification of music in response to infant states and cues; and integration of the family’s culture and music preferences. The music therapist facilitates and supports interaction between parents and infant. Parents learn how to adapt principles in relation to infant development across NICU hospitalization and post-discharge phases.

Discussion

The LongSTEP approach is feasible in culturally diverse countries where consistent parental presence is available, but requires tailoring to local circumstances and culture, particularly in the post-discharge phase. The emphasis on parent-led infant-directed singing places a higher demand on parents than other MT approaches, and requires sufficient psychosocial and musical support for parents.

Introduction

Each year, approximately 15 million infants are born prematurely, making preterm birth one of the world’s biggest health challenges (Chawanpaiboon et al., Citation2019). Prematurity is associated in the long term with poorer mental health, cognitive development, and quality of life (Chawanpaiboon et al., Citation2019; Fevang et al., Citation2016). Premature infants require advanced medical care, and the preterm family will often spend weeks or months in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), depending on the severity of the infant’s condition. Until the 1980s, NICU environments were often noisy and brightly lit places that exposed vulnerable premature infants to excessive and potentially harmful stimuli. Additionally, preterm infants and their parents faced long-term separation from each other as nurses and medical staff took on the primary caregiving roles during NICU hospitalization (Jolley & Shields, Citation2009). In the early 1990s, parent-driven grassroots organizations in the US demanded that parents receive easier access to information, inclusion in decision-making and more control over their children’s care in the NICU (Gooding et al., Citation2011; Johnson, Citation2000; Jolley & Shields, Citation2009).

Following an organized collaboration between families and physicians, the establishment of The Principles for Family-Centered Neonatal Care (FCC) (Harrison, Citation1993) marked a paradigm shift in neonatal care and enabled greater integration of family-centered care within best practice (Hutchfield, Citation1999; Lawlor & Mattingly, Citation1998; MacKean et al., Citation2005). Early FCC initiatives resulted in models of care that involved the entire family in treatment planning, and empowered parents to take active roles in caregiving as part of the greater team. Developmental care models, such as the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program (NIDCAP) (Als, Citation1986, Citation2009) and Mother Infant Transaction Program (MITP) (Rauh et al., Citation1988), based on Sameroff’s transactional model (Sameroff, Citation2009; Sameroff & Mackenzie, Citation2003), have also contributed to improving NICU environments and care practices. Such care models provide strategies and tools to promote optimal conditions for infant neurological development and growth while also supporting parent-infant mutual processes such as the development of parent-infant bonding (Puthussery et al., Citation2018).

Despite these advances, preterm birth and NICU hospitalization are still demanding and often traumatic experiences that pose various risks for both premature infants and their parents. Parents of premature infants often experience high levels of stress, anxiety and fear for their infant’s life (Bidzan et al., Citation2009), resulting in a greater risk of postpartum depression, significant stress (Sloan et al., Citation2008), and post-traumatic stress disorders (Korja et al., Citation2008; Muller-Nix et al., Citation2004; Winter et al., Citation2018). These mental health problems can in turn affect parental sensitivity and the capacity to respond appropriately towards the infant’s cues (Bozzette, Citation2007; Field, Citation2010). Meeting the premature infant’s physical and medical needs is a primary focus in neonatal intensive care, and although this focus is necessary and life-saving, it may alienate parents and affect the important relationship between parents and infant negatively (Bidzan et al., Citation2009). Parents must take on a role during NICU hospitalization that is challenging and complex, and that may compromise their ability to manage their own crisis of giving birth to a premature infant (Van Wassenaer‐Leemhuis et al., Citation2016). The importance of addressing parents’ own needs for emotional support is an emphasized part of FCC, but has been found to be the least developed aspect of FCC globally (Raiskila et al., Citation2016).

Although most contemporary NICUs have successfully reduced excess noise, the NICU environment and the care experienced within it still expose vulnerable infants to a range of unfamiliar and potentially overwhelming sensory input in the form of noise, smell, light and touch. The neuroplasticity of the developing premature infant’s brain allows for adaptation and growth (Brummelte, Citation2017), but at the same time represents a risk for maladaptation in response to harmful or mismatched conditions in the environment, including mismatched parent-infant interaction (Brummelte, Citation2017; Flacking et al., Citation2012; Schore, Citation2001). Moreover, the premature infant’s neurological immaturity results in subtle and quickly changing behavioral states and cues that can be difficult to interpret, increasing the risk for mismatched interaction and overstimulation of the infant (Bozzette, Citation2007; Sansavini et al., Citation2015). Conversely, sensory deprivation has been identified as a risk to premature infants residing in individual family rooms when consistent parental presence is lacking (Jobe, Citation2014).

The sound environment is particularly relevant when considering the risk of overstimulation and sensory deprivation. The sense of hearing becomes fully functional during the second trimester of pregnancy around week 25, exposing the fetus to external sounds (Graven & Browne, Citation2008; Hepper & Shahidullah, Citation1994; Moon, Citation2011). Experiments measuring fetal movement in response to external sounds have found fetal response as early as 19 weeks of pregnancy (Hepper & Shahidullah, Citation1994). The first sounds the fetus hears relate to social activities and voices, with maternal voice being dominant (Moon, Citation2011). Full-term newborns demonstrate a preference for their mother’s voice (DeCasper & Fifer, Citation1980; Lee & Kisilevsky, Citation2014) and for infant-directed speech (Cooper & Aslin, Citation1990), which has implications for the role that parental voice plays. Parental voice provides a critical orienting link between the fetal auditory environment and the auditory environment experienced in the NICU (Loewy et al., Citation2013).

From birth, infants exhibit abilities related to perception of music that resemble those of adults (Trehub, Citation2001). Infants perceive communicative signals from their parents and in turn can stimulate communicative responses from them (Malloch, Citation1999). The cooperative and coordinated interactions that result from this communicative exchange are musical in nature. In particular, coordinated elements of pulse, quality and narrative combine to constitute communicative musicality (Malloch, Citation1999; Malloch & Trevarthen, Citation2009). The theory of communicative musicality provides a framework for music therapy (MT), where music’s potential for connection, communication and interaction is the main focus. This theory, along with recognition of the central role of parental voice, has influenced the development of MT with premature infants and their parents.

Music therapy was first introduced to NICUs in the early 1990s through the pioneering work of Jayne Standley and colleagues (e.g. Cassidy & Standley, Citation1995; Standley, Citation1991). Their early work focused on the effects of audio stimuli on premature infants. Later clinical practice and research have incorporated live music and singing, increasingly including parents and family in MT (e.g. Cevasco, Citation2008b; Loewy, Citation2015; Shoemark, Citation2011b; Shoemark & Dearn, Citation2008). Several central contributors have highlighted the importance of song and parental voice. Shoemark (Citation2011b) translated infant-directed singing to a strategy for hospitalized families, and emphasized empowering parents to sing and actively participate in MT (Shoemark, Citation2017; Shoemark & Dearn, Citation2008). Loewy (Citation2015) emphasized the significance of family culture and musical preferences within her concept of song of kin, and evaluated its use in a clinical trial (Loewy et al., Citation2013). Haslbeck (Citation2014; Haslbeck & Bassler, Citation2020) contributed with an interactive, improvisational approach based on creative MT therapy, acknowledging the premature infant as an active partner and tailoring music to infant cues. Mondanaro et al. (Citation2016) emphasized the unique contribution of fathers and the benefit of including both parents. Shoemark (Citation2018) extended the impact of the music therapist’s skillset by designing the parent education program Time Together, a single parent education session aimed at facilitating quality of parent-infant interaction through musical exchange.

Despite advances in practice and theory in neonatal MT, there is still a lack of experimental research exploring mutual outcomes of parents and infants, especially within a longer-term context. Informed by the aforementioned notable contributions, we propose a MT approach for contexts with a high degree of parental presence in the NICU, with an extension of MT from hospitalization through the first six months at home. The purpose of this article is to present the theoretical framework and intervention protocol for this resource-oriented MT approach for premature infants and their families. The LongSTEP MT approach is used within a multinational randomized controlled trial, and is centered around parent-driven infant-directed singing, developmentally appropriate interaction, and longer-term mutual benefits of MT for parents and infants. The LongSTEP approach to MT for premature infants and their caregivers is described in short in the trial protocol (Ghetti et al., Citation2019). In this article, we define and explain the theoretical underpinnings and principal guiding principles of the approach. We also illustrate how these principles manifest in MT sessions, describe frames for the phases of the intervention, discuss prerequisites required for implementing this specific approach and present hypothesized mechanisms of therapeutic change.

Context and prerequisites

The approach to MT described herein was developed for the international randomized clinical trial, LongSTEP (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03564184). The study is designed as a 2 × 2 factorial, multinational, assessor-blind pragmatic randomized controlled trial to evaluate the longitudinal effects of MT on preterm infants and primary caregivers across 12 months. Premature infants and parents were recruited from eight NICUs in Argentina, Colombia, Israel, Norway, and Poland. Randomization occurs at study enrollment and at discharge from the NICU, resulting in four conditions: (a) MT during NICU, (b) MT after discharge, (c) MT during NICU and after discharge, or (d) standard care without MT. During hospitalization, families participate in three MT sessions per week, and monthly (two sessions in the first month) for a six-monthperiod following discharge. The main aim of LongSTEP is to evaluate the impact of MT on parent-infant bonding at six and 12months corrected age, as measured by the Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ) (Brockington et al., Citation2001). The secondary aim is to examine the effects on caregiver mental health and infant development. Eligible premature infants are born <35 weeks gestational age (GA), likely to be hospitalized at least two weeks from inclusion, and declared by NICU staff as medically stable to start MT (typically after 26 weeks postmenstrual age [PMAFootnote1]) (Ghetti et al., Citation2019).

The LongSTEP approach is intended for level III and IV NICUsFootnote2 where parental presence and participation are high. Hence, national parental leave policies that enable parents to be consistently present throughout hospitalization and for follow-up sessions after discharge are required for successful implementation. Each NICU must also support family-centered care principles of consistent parental presence and active participation in care, and parents must be willing to engage actively in MT sessions according to the LongSTEP approach through singing and using their voices, talking about infant and personal needs, and sharing musical preferences. The approach was originally developed within a Norwegian context (Ghetti et al., Citation2021) where infants have the legal right to parental presence at all times during hospitalization, and where family-centered care is consistently practiced (NOBAB, Citation2002). In the following, we specify foundational aspects of the approach and articulate the principal guiding elements that we consider essential and unique.

Guiding principles of the LongSTEP approach

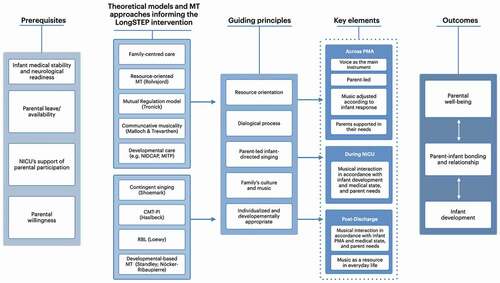

The LongSTEP approach is informed by several theoretical constructs from existing MT models and research, as well as by developmental psychology and neuroscience. To promote safe uses of music with this vulnerable population, the approach includes progressive expansion of musical complexity and interaction in alignment with infant gestational age and readiness, consistent with guidelines for MT on NICUs (Standley & Walworth, Citation2010; Nöcker-Ribaupierre, Citation2013; Standley & Gutierrez, Citation2020), and recommendations for noise levels in NICUs (American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Environmental Health, Citation1997; White et al., Citation2013). The LongSTEP approach: (a) is explicitly resource-oriented, (b) is directed toward the parent-infant dyad/triad to support mutual processes between parent(s) and infant(s) and promote mutual benefits, (c) positions parental voice as the central and most important musical component of the musical interaction, (d) is aligned with family-centered and developmental care principles, and (e) aims to support parents in the evolving relationship with their developing infant so that the MT has relevance during NICU hospitalization, and also across infancy after discharge. provides an overview of the prerequisites of the LongSTEP approach, the theoretical models and previous MT approaches informing it, as well as the approach’s guiding principles, essential elements and desired outcomes.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework and key elements of the LongSTEP approach

A resource-oriented approach

A resource orientation consistent with that described by Rolvsjord (Citation2010) is central to the LongSTEP approach and provides theoretical guideposts for the use of MT. Though Rolvsjord (Citation2010) situates her theoretical elaboration within the context of mental health care, she also envisions the transfer of her concepts to practices in other contexts. Her sensitizing concepts that characterize a resource-oriented approach serve as guiding values in the LongSTEP approach to MT, namely: (a) focusing on nurturing strengths, resources and potentials, (b) viewing the therapeutic encounter as a collaboration between client/user and therapist, (c) acknowledging and understanding the individual within their context, and (d) understanding music as a resource (Rolvsjord, Citation2010, p. 74). The fostering of inherent musical and parental resources is a central aspect of our approach. Parental voice, musical preferences, repertoire, culture and experiences are considered essential resources that can contribute to the formation of parental identity and self-confidence in parents and serve as tools to help them engage sensitively with their premature baby (McLean, Citation2016a; McLean et al., Citation2018). Parental voice is considered particularly important as it is an innate, accessible resource (Rolvsjord, Citation2004), and it provides the infant with a familiar and preferred sound that one can assume affords a sense of security in the unfamiliar NICU environment (Loewy, Citation2015; Shoemark, Citation2011b). Parents can be empowered through gaining access to and control over their resources, which may be particularly important in times of hardship and challenge (Rolvsjord, Citation2004).

Parents and infants possess the capacity to engage in reciprocal musical dialogue through coordinated communicative interactions (Malloch, Citation1999). Coordination between the communicative elements of pulse, quality and narrative combines to constitute communicative musicality (Malloch, Citation1999; Malloch & Trevarthen, Citation2009). Parental voice and the potential for communicative musicality may serve as health resources in congruence with a resource-oriented approach to MT (Rolvsjord, Citation2010). In our approach, parents become aware of how to attune to their infants and engage in cooperative communicative exchange. By actively carrying on these attuned musical interactions in a variety of parent-infant situations, parents and infants actively participate in using music as a health resource.

Consistent with Rolvsjord (Citation2010, p. 78), we view therapeutic change as occurring via a collaboration between the music therapist, parents and infant(s) that emphasizes equality, mutuality and participation. Though we acknowledge that the music therapist possesses expertise, we problematize the positioning of the therapist as “expert” in relation to parents. Instead, we emphasize parents’ developing expertise in knowing their infants, and support them in taking a lead as they engage in musical exchange. In our approach, both parents and music therapists share responsibility for what happens in MT, although they have different roles (Stige, Citation2002). Both have shared responsibility for forming a shared goal for a session, finding ways to work together and with the infant, and evaluating how these efforts have gone (Rolvsjord, Citation2010). Through a supportive approach and collaborative dialogue, the therapist helps parents to identify and expand their musical resources and learn to interpret and respond to their infant’s subtle signals via the musical interaction. The infant, in turn, participate with mutuality, responding as a communicative partner and making their needs known. These musical exchanges occur in response to infant states and cues as they evolve over time. Exchanges can result in musical attunement between the parent and infant (Stewart, Citation2009), and contribute positively to parents experiencing a relationship with their baby (Haslbeck, Citation2014; Ghetti et al., Citation2021).

A mutual process for mutual benefits

The LongSTEP approach views MT as a dialogical process that enables mutual regulation beneficial for both parents and infants. Our view of MT is, to a large degree, informed by developmental psychology, attachment theory, and research on early communication and interaction, with a particular emphasis on the significance of the human voice. From modern developmental psychology we, like several other neonatal MT approaches, adopt the view of the newborn baby, both full-term and premature, as a competent, relational being, entering the world with a capacity and need to interact with and relate to its close surroundings (Brazelton, Citation1978; Chamberlain, Citation1987; Slater, Citation1998). The newborn is, however, still very much dependent on available, sensitive caregivers to develop in a healthy manner. Self-regulation is a crucial capacity developed through interaction with close caregivers, recognized for its important role in promoting healthy development and wellbeing across the lifespan (Murray et al., Citation2015). In infants, self-regulation is exemplified when an infant intentionally disengages from an external stimulus, such as when averting their gaze (Rothbart et al., Citation1992). In early infancy, self-regulatory capacities begin developing through co-regulation or mutual regulation, where parents sensitively attune to infant cues and provide nurturing support through responsive interactions to calm and soothe the infant (Murray et al., Citation2015). Beeghly et al. (Citation2011) argued that maternal sensitivity is best understood as a dyadic construct and as a component of the infant-caregiver communication system which is mutually regulating. The Mutual Regulation Model (Tronick, Citation1989) proposes that this dyadic mutually regulating communication system is made up of an infant subsystem, a parental subsystem, and the dynamic interaction between these subsystems (Beeghly & Tronick, Citation2011). According to this model, the success or failure of mother-infant mutual regulation depends on four reciprocal processes: (a) infants’ ability to self-organize and control their physiological states and behavior; (b) the integrity and maturation of sensorimotor, attentional, and social–emotional elements of infants communicative system (e.g. gestures, gaze shifting, affective displays); (c) parents’ ability to apprehend and correctly interpret their infant’s communications; and (d) parents’ motivation and capacity to respond to their infant contingently and appropriately to facilitate their infant’s regulatory efforts (Beeghly & Tronick, Citation2011, pp. 197–198).

As premature infants are neurologically immature, and often medically compromised, they do not have the same capacity to self-organize and control their physiological states and behavior as full-term newborns (Feldman, Citation2009). Their behavioral states can shift rapidly and communication cues are often subtle, making them harder for parents to interpret (Richards, Citation2014). Developmental and family-centered care models, such as NIDCAP and MITP, involve guiding parents in understanding their baby’s behavioral cues, and hence enabling them to provide developmentally appropriate and sensitive responses (Als, Citation2009; Rauh et al., Citation1988), which in turn contributes to establishing a good foundation for the parent-infant relationship (Beeghly et al., Citation2011; Tronick & Beeghly, Citation2011). Such guidance can foster mastery and self-confidence in parents (Puthussery et al., Citation2018).

It is, however, important to keep in mind that parents of premature infants often feel overwhelmed and are at risk of higher levels of stress and anxiety which may impair their responsivity towards the premature infant (Winter et al., Citation2018). It is thus important that the psychosocial needs of the parents are attended to in order to promote parental sensitivity, successful mutual regulation and interaction. Psychotherapeutic support can be offered through providing space for parents to share feelings and concerns, and receive their own musical self-care, as a way to support resilience in their caregiving roles (Loewy, Citation2015). For the LongSTEP approach to be successful, both infants and parents must be addressed in relation to their individual as well as mutual needs (Stewart, Citation2009). The LongSTEP approach is distinguished from parent education programs such as Time Together (Shoemark, Citation2018) in that sessions are conceived of as MT with therapeutic focus directed toward the parent-infant dyad/triad, and the music therapist provides psychotherapeutic support for parents during the course of MT to the extent that such support helps parents be present for their infant(s).

Parental voice is central

Parents singing for their babies is a cross-cultural phenomenon that represents an innate parental resource and act of caregiving behavior that has likely been around at all times (Dissanayake, Citation2009; De l’Etoile, Citation2006). For parents in crisis, talking to their infants might seem more natural than singing (Shoemark & Arnup, Citation2014). Developmental theorists have extensively investigated parent-infant interaction, and in particular the way mothers speak to their children (Beebe & Lachmann, Citation1988; Malloch & Trevarthen, Citation2009; Nakata & Trehub, Citation2011; Papoušek, Citation1996; Papoušek et al., Citation1991; Trainor et al., Citation2000; Trehub, Citation2001, Citation2009; Trehub & Trainor, Citation1998; Trehub et al., Citation1997; Trevarthen & Malloch, Citation2000). Maternal speech, motherese, or infant-directed speech are some of the terms used for the characteristic music-like way parents use their voices when engaging with their baby. Infant-directed (ID) speech has higher pitch, more exaggerated pitch contours, larger pitch range, slower tempo, and is more rhythmic than typical adult-directed (AD) speech (Trainor et al., Citation2000). Saliba et al. (Citation2020) found that both maternal and paternal ID speech promoted a quiet alert state in preterm infants, which is the behavioral state where the infant is most available and ready to engage (Beeghly & Tronick, Citation2011; Brazelton & Nugent, Citation1995; Nugent et al., Citation2007).

Infant-directed singing shares many features with ID speech, but singing additionally offers more structure through musical form, with more distinct and predictable phrasing, melodic range, and rhythmical patterns (Trehub & Trainor, Citation1998; Trehub et al., Citation1997). De l’Etoile (Citation2006) suggests that “similarities between mother-infant interaction and ID singing provide a logical starting point for clinical interventions in music therapy” (p. 22). Furthermore, there is evidence that ID singing both captures the infant’s attention and has regulating qualities delaying distress (Corbeil et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; Filippa et al., Citation2017; Saliba et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). Shoemark (Citation2011a) proposed the concept of contingent singing to highlight the mutuality of interaction between the person singing (in her original conceptualizations, the music therapist) and the infant being sung to. The infant is not yet making his own music, but is an active participant, affecting and informing the song and interplay provided by the person singing. Filippa et al. (Citation2020) found that contingent vocal interaction of parents, both speaking and singing, increased self-touch, eye-opening, and oral behaviors in premature infants. Infants responded differently to maternal singing than to maternal speech, however, demonstrating more rhythmical sucking behaviors and smiles to maternal singing, and more non-rhythmical mouth movements to maternal speech (Filippa et al., Citation2020). Singing might also offer parents a sense of both normality and intimacy, and a different way of relating than the typical NICU hospitalization experience (McLean, Citation2016b; McLean et al., Citation2018; Shoemark & Dearn, Citation2008).

A family-centered approach

Eight principles of patient-centered and family-centered care for newborns in neonatal intensive care were suggested by the European Science Foundation (ESF) European Research Network on Early Developmental Care in 2005, and later reviewed by Roué et al. (Citation2017). These principles are evidence-based and are recommended as a worldwide standard (Roué et al., Citation2017). The principles include free 24-hour parental access, psychological support for parents, pain management, supportive environment, postural support, skin-to-skin contact, breastfeeding and lactation support, and sleep protection (Roué et al., Citation2017). Families are recognized as having the greatest influence on a child’s health and wellbeing, and parents are ensured active participation in treatment and care. To support parents in their active role, nurses and other medical staff work in partnership with parents, demonstrating, explaining and supporting, rather than merely directing parents (Johnson, Citation2000). Family-centered care can shorten the total length of hospital stay for premature infants (Yu & Zhang, Citation2019), and is increasingly viewed as best practice in child health-care settings (Hutchfield, Citation1999; Lawlor & Mattingly, Citation1998; MacKean et al., Citation2005). However, FCC remains a somewhat broad concept that lacks standardization, resulting in a variety of different understandings of what comprises FCC, and how these values should be translated into action in a way that honors each individual family (Dennis et al., Citation2017; Kokorelias et al., Citation2019).

Consistent with Ullsten et al. (Citation2020, p. 67), in the LongSTEP approach we consider and respect each family as a unique entity with its own musical history, musical preferences, and unique intergenerationally transmitted attachment patterns. Parent participation and decision-making are essential for the collaborative and resource-oriented MT process of the LongSTEP approach, and to support parents in the development of their parental role (Broom et al., Citation2017).

Relevant for the infant’s early development in the NICU and beyond

In a meta-analysis of randomized trials of MT for premature infants and their caregivers, Bieleninik et al. (Citation2016) identified a substantial evidence gap related to the longer-term impact of neonatal MT, and the effects of intervention periods extending past discharge from NICU. The post-discharge phase of the LongSTEP approach addresses this gap by enabling continuity of care that bridges from hospital to home (Ghetti et al., Citation2019). A baby’s first 1001 days, from conception until two-years-old, is increasingly considered a critical period that affects health and wellbeing throughout life (Leach, Citation2017; Leadsom et al., Citation2013). When working with families, this time window offers unique possibilities. A range of intervention programs aim to support the development of premature infants, with a majority including parents as active participants. In a meta-review, Puthussery et al. (Citation2018) found that intervention programs with home and facility-based components for parents of preterm babies affected the quality of the maternal-infant relationship, mother-infant interactions, symmetrical and asymmetrical co-regulation, mutual attention, and maternal sensitivity and responsiveness. Van Wassenaer‐Leemhuis et al. (Citation2016) reviewed randomized controlled trials of home-based family-centered intervention programs in very preterm infants aiming to improve cognitive outcomes, and concluded that research aimed at improving outcomes in premature infants must continue after discharge from the NICU. The evidence-base suggests that both infant development and parent-infant relationships develop over time, and interventions should be designed and offered accordingly. In LongSTEP, we offer MT beyond NICU hospitalization through a six-month period. In a feasibility study of the approach, parents expressed that they have found it particularly interesting to note the increasing responsiveness and interaction with their child over time (Ghetti et al., Citation2021). To our knowledge, LongSTEP is the first RCT to investigate the effectiveness of MT extending from NICU hospitalization through 6-months post-discharge.

Key aspects of the LongSTEP approach

The following description of the LongSTEP approach is an elaboration of the MT intervention description provided in the study protocol (Ghetti et al., Citation2019) tying it more clearly to the aforementioned theoretical basis. This elaboration includes a description of preparations to be made before initiating MT sessions and essential elements of the approach, as well as a discussion of aspects specific to the two phases of the intervention.

Before beginning the actual MT sessions, we propose that the therapist should meet with the family twice. First, to begin to develop therapeutic rapport, introduce basic concepts and potential aims of MT, map the family’s musical preferences and experiences, and get to know other aspects that are important for the family, for example, cultural background and religious or spiritual beliefs. Second, we propose a separate session where the music therapist observes parent-infant interaction in a situation that involves handling, for example, during diaper change, physiotherapy, or transitions from incubator/cot. Such observations can provide insights into infant development, thresholds for overstimulation, and early strategies for self-soothing. This observation also demonstrates how parents interpret and respond to their baby’s cues and states.

Essential elements and fidelity assessment

Seven elements (summarized in and described in detail below) are considered essential for the LongSTEP approach, and should be manifest in each session regardless of the infant’s postmenstrual age and development or the phase in which MT is provided. These elements describe the essential aspects of the approach in a form that is discretely observable for the purposes of treatment fidelity assessment. These essential elements form the basis for treatment fidelity assessment tools in the project. The descriptions and the assessment tools have been pilot tested; the results of treatment fidelity will be reported separately.

Table 1. Essential elements of the LongSTEP approach

Observation and dialogue on the infant needs prior to and during MT sessions

Like the two preparation sessions, this introductory part of each session allows for an initial observation of the infant’s current state and readiness for interaction. The observation should begin with some brief quiet time, where the therapist and parents watch the infant together to identify its current state and needs at that moment. This includes looking at physiological aspects such as respiratory rate and pulse, skin color, motor activity and quality of movements, sleep and awake states, and responsivity, similar to how it is carried out in newborn behavioral observation (NBO) sessions (Nugent et al., Citation2007). Parents are then invited to have a dialogue on their observations and thoughts on what their baby might need or benefit from at that particular moment. Additionally, adjustments are made to ensure that the infant is physically positioned to promote self-regulation. Most infants will either be held by the parent or positioned so that the infant’s arms and legs are gently supported in a tucked and flexed position, with arms supported so that the infant’s hands come towards midline. These principles of facilitated tucking and support for midline alignment can help to promote physical containment and autonomic regulation, enhancing general behavioral development (Hill et al., Citation2005; Hunter, Citation2010; Vergara & Bigsby, Citation2004). If the infant is drowsy, parents can promote quiet alertness by positioning the infant slightly more upright. The first part of the session helps to prepare the infant and parent for developmentally appropriate musical interaction and functions as an initiation into the collaborative and dialogical exchange that characterizes the therapeutic approach. Identifying the specific needs of the infant and discussing how music and voice can serve these might also add meaning to the act of singing for parents who are not motivated or feel insecure (Shoemark, Citation2017).

Dialogue with parents on their state and needs prior to a session

Since parents of premature infants can experience significant stress and traumatization associated with premature birth, and this intervention aims to support mutual outcomes of both infant and parents, it is important to give sufficient attention to parents’ own needs and concerns. There is a consensus that parent wellbeing and mental health affect parent-infant interaction (Beeghly et al., Citation2011; Field, Citation2010; Korja et al., Citation2008), and parents of preterm infants are particularly vulnerable (Flacking et al., Citation2012; Korja et al., Citation2008; Lasiuk et al., Citation2013; Loewy, Citation2016; Misund et al., Citation2013; Muller-Nix et al., Citation2004; Sloan et al., Citation2008; Stewart, Citation2009). Therefore, attending to parents’ own need for stabilization, self-regulation, and restorative experiences forms a necessary part of the intervention, in alignment with trauma-preventive approaches to NICU MT (Loewy, Citation2016; Stewart, Citation2009). The music therapist provides space for parents to share feelings prior to and during sessions, and helps shape sessions to address parents’ needs. Thus, parents’ need for stabilization, self-regulation, integration of traumatic experience, and restorative experiences (Stewart, Citation2009) might dominate in portions of a session, and the therapist gently brings the focus back to the parent-infant interaction when appropriate.

Voice serves as the main instrument

For parents, the voice is an innate resource, accessible at all times. Parental voice forms a supportive environment for the premature infant (Roué et al., Citation2017), and parental singing promotes the formation of parental identity (McLean, Citation2016a). In the LongSTEP approach, parents are empowered to use their singing and spoken voices in an infant-directed manner, such that parental voice consistently serves as the main instrument. Singing can reduce arousal for parents and infants (Cirelli et al., Citation2020), enable parents to experience emotional closeness (Fancourt & Perkins, Citation2018), and help parents experience and contain a broad range of feelings to help them work through challenging emotions (McLean, Citation2016a). The stabilization and mutual regulation that occur during infant-directed singing may then enhance parents’ quality of presence and sensitivity when interacting with their infant. The music therapist guides and musically supports parents in attuned use of their voice. Other musical instruments, such as guitar or monochord, are used in moderation, preferably only when requested by parents or when considered necessary to encourage continuation of parental singing (Ghetti et al., Citation2019). At times, particularly during initial sessions, parents can feel insecure about singing, and simple instrumental accompaniment can be of help. Such accompaniment should be delivered in an infant-appropriate way with adjusted tempo, volume, and level of complexity.

Parental voice serves as the most prominent musical voice

Acknowledging the central importance of parental voice (e.g. Filippa et al., Citation2017; Saliba et al., Citation2020), the music therapist provides adequate space and support so that parents can become comfortable, gradually taking on a leading role in singing and/or using an attuned spoken voice. The therapist assures that parental voice is clearly distinguishable during MT sessions by modifying their own singing volume to take on a supportive musical role when singing together with the parents. Through demonstration, the therapist guides parents in how to adjust musical elements such as pitch, tempo and rhythm to tailor musical interaction to infant needs and responses (Haslbeck, Citation2014; Nöcker-Ribaupierre, Citation2013; Shoemark, Citation2011b) so that the infant, in effect, “directs” the parents’ way of singing. Later in the therapeutic process as the infant matures, touch and movement can be integrated into sessions (Nöcker-Ribaupierre, Citation2013).

Music therapist provides opportunities for parents to participate actively

The music therapist encourages and guides parents to sing or hum in an infant-directed way, and invites them to touch and move their infant in response/relation to the music (when tolerated). If parents are reluctant to sing, the music therapist offers alternative ways of participating, such as writing lyrics or modifying existing lyrics of significant parent-chosen songs (Ettenberger & Ardila, Citation2018; Loewy, Citation2015) that can be used in future sessions. The music therapist creates adequate space for parents both musically and verbally, and asks questions to help parents reflect on what they do musically and how the infant responds (both inside and outside the session).

Music is modified to infant cues and responses

During introductory sessions, the music therapist introduces the concept of infant-directed singing and describes how parents can attend to and modify music according to their infant’s state and engagement and disengagement cues. Parents learn how to begin with single tones or single words matched to infant breathing patterns, facial expressions and movements, and over time begin to add more complexity in terms of melodic contour, rhythmicity, phrasing and multisensory aspects of touch and rocking. Parents learn how to simplify the musical interaction when the infant shows signs of disengagement by slowing tempo, simplifying the melody or lyrics, or providing a temporary pause. However, the music therapist has overall responsibility for providing music safely for the developing infant. Thus, it is important that the music therapist using this approach has thorough training in recognition of infant engagement and disengagement cues. Such training, as provided to the therapists in this study, maximizes therapist competence in safely facilitating the approach. Further specification of our progressive sequence is found below and in the protocol (Ghetti et al., Citation2019).

Parents’ culture and musical preferences and abilities are integrated into sessions

Parents are encouraged to share preferences and personally significant familiar songs that are subsequently adapted in an infant-appropriate manner and integrated within the session. Loewy (Citation2015) refers to these songs as songs of kin, which include both lullabies and other types of music (e.g. parent-preferred popular music, music representing parents’ nationality/culture/religion/beliefs, etc.). The music therapist accommodates parents’ levels of musical experience and modifies music accordingly (e.g. selects a comfortable vocal range) to facilitate parental musical engagement.

Aspects specific to MT during NICU hospitalization

Families in the LongSTEP study that receive MT during NICU hospitalization commit to participating in three sessions per week. This frequency ensures: that the infant’s evolving needs are addressed in a timely manner; that parents have ample opportunities for practice, repetition and constructive dialogue with the therapist; and that parents’ own psychosocial needs can be met during the course of a NICU stay. We aim for a minimum of six sessions in the NICU, and conclude at a maximum of 27 in order to conserve resources and minimize heterogeneity among participants. Sessions last between 30 and 40 minutes, with time spent actively making music typically lasting from 15 to 30 minutes in accordance with infant tolerance (Standley & Walworth, Citation2010; Nöcker-Ribaupierre, Citation2013).

Music therapy can be provided during kangaroo-care, feeding or with the infant lying in the incubator or cot. In the NICU phase of the intervention, although declared medically stable for MT, infants are smaller, more neurologically immature and medically fragile than in the post-discharge phase. Following Nöcker-Ribaupierre’s (Citation2013) guidelines, MT with infants of GA 26–32 weeks should contain primarily cautious use of singing and toned voice without accompanying instruments. Predominantly wordless singing is matched to infant responses, aiming to promote sleep or quiet alert state, depending upon infant need (Ghetti et al., Citation2019; Nöcker-Ribaupierre, Citation2013). From week 32 onwards, previous elements can be expanded upon by including dynamic touch, parent facial expressions and gesticulations, vocal inflection and phrasing to promote musical interplay, rudimentary musical dialogue and social interplay with the infant. The physical location of sessions should be considered since aspects of the physical environment can affect parental comfort with singing (Ghetti et al., Citation2019). If private spaces are not available, the use of folding screens can help create a more intimate atmosphere in open bay units. Music therapists should collaborate with parents and staff to ensure that sessions do not interfere with other treatment appointments or care routines. Preterm families often receive a range of services during hospitalization, and MT should not occur directly following sensory-demanding procedures or therapies due to the risk of overstimulation.

Aspects specific to MT after discharge from hospital

The sessions after discharge are provided monthly over a period of six months in the LongSTEP study, with two sessions during the first month to enable assessment and rapport building (particularly important for families who did not have MT during NICU hospitalization in the study). Providing seven sessions in the first six months enables the development of a collaborative alliance between parents and music therapist where musical interaction approaches can be tailored in alignment with infant development over time, and the changing needs of infant and family. Monthly sessions assure that parents have time to develop skills and practice in their daily lives between sessions. Infants who have been discharged home are typically more stable and more neurologically mature than those who are hospitalized. Consequently, musical interaction in the post-discharge phase can include more complexity and longer periods of active music-making, depending upon infant tolerance. Post-discharge sessions last between 45 minutes and one hour, and follow a set structure with approximately 15 minutes spent in verbal dialogue during the session (Ghetti et al., Citation2019). Considering that we aim for parents to use musical interactions in their everyday lives and contexts, it is ideal for sessions to occur in the family’s home, but they can also be held at the hospital or other health-care settings convenient for the family. Family needs are assessed at the beginning of sessions, and parents are asked to identify particular strengths and challenges they are experiencing. Parents then discuss various approaches with the music therapist to meet these needs and can attempt such while receiving support from the therapist (Ghetti et al., Citation2019). Siblings who are available may be included in the sessions in an attempt to make the interactions more relevant to real-world family dynamics.

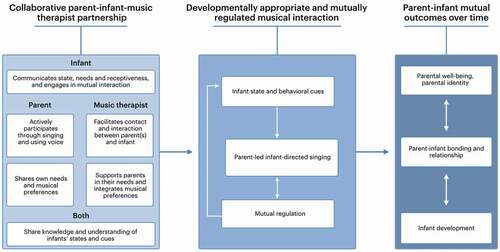

Proposed mechanisms of action

illustrates the proposed mechanisms of action of the LongSTEP approach. A foundation of this approach is the collaborative partnership between parents, music therapist, and infant(s), where general knowledge on premature infant development and specific knowledge of the individual infant’s needs and preferences are shared. In this relationship, the music therapist supports parents in regard to their immediate psychosocial needs (e.g. fear, hopelessness, traumatic stress responses), and their developing sense of parental identity and relationship with their infant. This partnership lays the foundation for parents feeling comfortable enough to explore the use of song and voice with their infant while receiving musical and emotional support from the music therapist. The music therapist facilitates interaction between parents and infant, supporting an attuned form of early dialogic communication that improves the quality of their relationship. The therapist models techniques and principles, and encourages parents to try these out with support. The infant possesses the potential for communicative musicality, and expresses either receptiveness to musical interaction or aversion to it via engagement and disengagement cues. The collaborative effort of the parents and the music therapist jointly interpreting and attending to the infant’s cues helps promote attuned, developmentally appropriate musical interactions that enable beneficial parent–infant mutual regulation. Parents are empowered to use inherent musical resources, including their voices and music preferences, to develop a relationship with their infant. By singing to their infants, parents experience a reduction in arousal. As parents become regulated themselves, they can more sensitively respond to their infants musically, promoting attuned interaction with their infant and enabling mutual regulation between them. Experiencing mastery in MT through recognizing infant responses to their voices and effectively meeting their infant’s needs, the parents’ sense of parental identity and perception of parent–infant bond may strengthen. With a secure parent–infant bond, parents can carry forward abilities they experience in MT to future attuned musical interactions with their infant, adeptly adapting the exchange as the infant develops. By building capacity for attuned musical interaction and enabling experiences of mastery and parental identity, we hope to improve the quality of relations between parents and infants, creating a basis for better parental mental wellbeing and, ultimately, improved infant development over time.

Critical reflections

The LongSTEP approach requires contexts where parental presence is encouraged and safeguarded throughout NICU hospitalization, and thus it may not be feasible to implement it in NICU settings where parental presence is limited. The approach places high demands on parents who might already feel overwhelmed by other tasks and responsibilities during NICU hospitalization. We support Shoemark (Citation2017) in acknowledging that singing is not a natural action for everyone, and that with today’s increasingly individualized music listening technology and decreasing opportunities for active music-making in many countries, people might be less connected to their musicality. The role of the music therapist in the LongSTEP approach is to support parents in the music therapeutic process in a power-balanced, non-directive, and collaborative manner. Experiences from training music therapists and implementing the approach in the study’s participating countries indicate that it may be challenging for music therapists to shift away from a familiar role of leading the music in order to provide adequate space for parents to take a lead. Although we strive for equality in the relationship between therapist and client through a resource-oriented approach, therapeutic relationships always involve power dynamics (McLean, Citation2016a; McLean et al., Citation2018; Rolvsjord, Citation2010; Shoemark, Citation2017), which must be acknowledged and actively challenged. A successful music therapist–parent partnership will be shaped by cultural and contextual factors, as well as the therapist’s previous experience, personality and skills (Edwards, Citation2014; Loewy, Citation2015; Shoemark & Ettenberger, Citation2020). It is important, therefore, that the music therapist is able to sensitively perceive and respond to complex layers of culture, context and experience; thus, capacity for self-awareness and self-reflection is key.

Supervision provides a tool for promoting capacity for self-awareness and self-reflection. Music therapists trained for the LongSTEP trial received supervision from the trial's core team, both individually and in smaller groups. Four of our participating sites had more than one music therapist while four music therapists were alone with the responsibility of providing the intervention. Therefore, we considered it important to combine individual supervision with group sessions, aiming to support successful implementation through promoting therapists’ self-awareness and providing a space where challenges could be discussed and experiences celebrated with peer support. Therapists reported that it was fruitful to share strategies from the different sites, which highlighted therapists’ individual strengths and weaknesses, as well as contextual and culturally specific themes and challenges. Music therapists who engage in clinical practice in a manner consistent with the LongSTEP approach are encouraged to seek regular clinical supervision to work through their experience of this sensitive work.

Conclusion

In this article, we have developed the theoretical rationale, guiding principles, essential elements, and proposed mechanisms of action of a MT approach for premature infants and their caregivers developed for an international pragmatic RCT. We have presented and discussed prerequisites and particular considerations for carrying out this approach during NICU hospitalization and during follow-up post-discharge. We hypothesize that many parents will need repetition, practice, support and constructive dialogue in order to make lasting changes and establish new ways of relating with their infant. However, other approaches such as Time Together (Shoemark, Citation2018) show that single parent education sessions can also have the potential to improve the quality of parent–infant interaction. Different approaches may meet families’ needs in different ways.

The LongSTEP approach is resource-oriented and family-centered, where infants and parents are supported in a dialogic MT process, aiming for mutual outcomes in the form of improved parent–infant bonding, parent wellbeing and infant development. In the LongSTEP study, we explore parental perception of parent–infant bonding. Future research could expand our understanding by exploring the impact of this MT approach on infant attachment to caregivers. LongSTEP is an international and multicultural research study. Further investigation of how cultural factors affect implementation and perception of the approach is needed.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our User Advisory Group (Trude Os, Anette C. Røsdal and Signe H. Stige) and members of the Scientific Advisory Committee (Deanna Hanson-Abromeit, Friederike Haslbeck, Małgorzata Lipowska, Joanne V. Loewy, Renate Nussberger, Helen Shoemark and Alexandra Ullsten) who provided valuable comments on developing the study protocol that informs the LongSTEP approach. We also thank Mark Ettenberger and the LongSTEP music therapists (Catharina Janner, Dana Yakobson, Hagit Ostrovsky, Julie Mangersnes, Justyna Kwasniok, Liron Lindeman, Luisa F. Aristizabal, Merethe W. Lindvall, Paula Macchi, Sara K. Szweda and Shulamit Epstein) for valuable discussions and input during intervention training and supervision.

Disclosure statement

Claire Ghetti is Associate Editor of the Nordic Journal of Music Therapy. To avoid conflict of interest, Claire Ghetti was fully masked to the editorial process including peer review and editorial decisions and had no access to records of this manuscript.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tora Söderström Gaden

Tora Söderström Gaden, PhD research fellow at NORCE Norwegian Research Centre, Bergen, Norway. She holds her music therapy master’s degree from the Norwegian Academy of Music and has clinical experience from pediatrics and neonatal care settings. She is certified in the “First Sounds: Rhythm, Breath, Lullaby” model for neonatal music therapy, and a certified Newborn Behavioral Observation (NBO) trainee.

Claire Ghetti

Claire Ghetti, PhD, MT-BC, CCLS is Associate Professor of Music Therapy at The Grieg Academy - Department of Music, University of Bergen, Norway; and Assistant Leader of the Grieg Academy Music Therapy Research Centre (GAMUT), NORCE Norwegian Research Centre AS, Bergen, Norway. She is currently Principal Investigator of LongSTEP (RCN 273534). Her research centres on how music and relationships that are enabled through music serve as resources that buffer against traumatization in intensive medical contexts. Claire has published research and theoretical work in music therapy: as procedural support, for hospitalized children at risk for traumatization and as emotional-approach coping. As a music therapist and certified child life specialist, she has pioneered music therapy programming within pediatric and neonatal intensive care. Claire holds a PhD in music therapy with a minor in health psychology from the University of Kansas.

Ingrid Kvestad

Ingrid Kvestad, PhD, PsyD, is a senior researcher and a clinical child psychologist at the Regional Centre for Child and Youth Mental Health and Child Welfare, NORCE Norwegian Research Centre, Bergen, Norway. Her main research interest is in early psychosocial and biological risks and the impact on child development. She is part of the core team investigators of LongSTEP (RCN 273534).

Christian Gold

Christian Gold, PhD, is Research Professor at NORCE Norwegian Research Centre AS, Bergen, Norway. He is also Adjunct Professor at the University of Bergen and at Aalborg University, Denmark, and Professorial Research Fellow at the University of Vienna. He serves as an Editor of the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group. He holds a music therapy degree from Vienna University of Music and Performing Arts, a PhD from Aalborg University, and a postgraduate degree in biostatistics from The Institute for Statistics Education, Arlington, VA, USA. His research includes randomized trials and systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions in mental health, as well as process-outcome research and reviews of research methodology.

Notes

1 Postmenstrual age is defined as gestational age at birth plus the time since birth (American Academy of Pediatrics, Citation2004).

2 Level III NICUs are hospital NICUs organized with personnel and equipment to provide continuous life support and comprehensive care for extremely high-risk newborn infants and those with critical illness, and level IV NICUs provide the highest level of neonatal care at a regional level with a full range of specialized services (Committee of Fetus and Newborn, Citation2012). In LongSTEP, seven of the included NICUs are level III and one level IV.

References

- Als, H. (1986). A synactive model of neonatal behavioral organization: Framework for the assessment of neurobehavioral development in the premature infant and for support of infants and parents in the neonatal intensive care environment. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 6(3–4), 3–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/J006v06n03_02

- Als, H. (2009). Newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program (NIDCAP): New frontier for neonatal and perinatal medicine. Journal of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine, 2(3), 135–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/NPM-2009-0061

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Environmental Health. (1997). Noise: A hazard for the fetus and newborn. Pediatrics, 100(4), 724–727. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.100.4.724

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2004). Age terminology during the Perinatal Period. Pediatrics, 114(5), 1362–1364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1915

- Beebe, B., & Lachmann, F. M. (1988). The contribution of mother-infant mutual influence to the origins of self-and object representations. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 5(4), 305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.5.4.305

- Beeghly, M., Fuertes, M., Liu, C. H., Delonis, M. S., & Tronick, E. (2011). Maternal sensitivity in dyadic context: Mutual regulation, meaning-making, and reparation. In D. W. Davis & M. C. Logsdon (Eds.), Psychology research progress. Maternal sensitivity: A scientific foundation for practice (pp. 45–69). Nova Science Publishers.

- Beeghly, M., & Tronick, E. (2011). Early resilience in the context of parent–infant relationships: A social developmental perspective. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 41(7), 197–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2011.02.005

- Bidzan, M., Bieleninik, Ł., Zdolska, A., & Salwach, D. (2009). Bond with a child in the prenatal period in case of prematurely born children. In K. Turowski (Ed.), Wellness and success (Vol. 3, pp. 35–54). NeuroCentrum.

- Bieleninik, Ł., Ghetti, C., & Gold, C. (2016). Music therapy for preterm infants and their parents: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 138(3), e20160971. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-0971

- Bozzette, M. (2007). A review of research on premature infant-mother interaction. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, 7(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2006.12.002

- Brazelton, T. B. (1978). The remarkable talents of the newborn. Birth and the Family Journal, 5(4), 187–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536X.1978.tb01276.x

- Brazelton, T. B., & Nugent, J. K. (1995). Neonatal behavioral assessment scale. Cambridge University Press.

- Brockington, I. F., Oates, J., George, S., Turner, D., Vostanis, P., Sullivan, M., Loh, C., & Murdoch, C. (2001). A screening questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disorders. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 3(4), 133–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s007370170010

- Broom, M., Parsons, G., Carlisle, H., Kecskes, Z., Dowling, D., & Thibeau, S. (2017). Exploring parental and staff perceptions of the family-integrated care model. Advances in Neonatal Care, 17(6), E12–E19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000443

- Brummelte, S. (2017). Introduction: Early adversity and brain development. Neuroscience, 342, 1–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.09.041

- Cassidy, J. W., & Standley, J. M. (1995). The effect of music listening on physiological responses of premature infants in the NICU. Journal of Music Therapy, 32(4), 208–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/32.4.208

- Cevasco, A. M. (2008b). The effects of mothers’ singing on full-term and preterm infants and maternal emotional responses. Journal of Music Therapy, 45(3), 273–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/45.3.273

- Chamberlain, D. (1987). The cognitive newborn: A scientific update. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 4(1), 30–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0118.1987.tb01000.x

- Chawanpaiboon, S., Vogel, J. P., Moller, A.-B., Lumbiganon, P., Petzold, M., Hogan, D., Landoulsi, S., Jampathong, N., Kongwattanakul, K., Laopaiboon, M., Lewis, C., Rattanakanokchai, S., Teng, D. N., Thinkhamrop, J., Watananirun, K., Zhang, J., Zhou, W., & Gülmezoglu, A. M. (2019). Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: A systematic review and modelling analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 7(1), e37–e46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0

- Cirelli, L. K., Jurewicz, Z. B., & Trehub, S. E. (2020). Effects of maternal singing style on mother–infant arousal and behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 32(7), 1213–1220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01402

- Committee of Fetus and Newborn. (2012). Levels of Neonatal Care. (2012). Pediatrics, 130(3), 587–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1999

- Cooper, R. P., & Aslin, R. N. (1990). Preference for infant‐directed speech in the first month after birth. Child Development, 61(5), 1584–1595. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1130766

- Corbeil, M., Trehub, S. E., & Peretz, I. (2013). Speech vs. singing: Infants choose happier sounds. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 372, 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00372

- Corbeil, M., Trehub, S. E., & Peretz, I. (2015, September 22). Singing delays the onset of infant distress. Infancy, 1(19), 373–391. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12114.

- De l’Etoile, S. K. (2006). Infant-directed singing: A theory for clinical intervention. Music Therapy Perspectives, 24(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/24.1.22

- DeCasper, A. J., & Fifer, W. P. (1980). Of human bonding: Newborns prefer their mothers’ voices. Science, 208(4448), 1174–1176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7375928

- Dennis, C., Baxter, P., Ploeg, J., & Blatz, S. (2017). Models of partnership within family‐centred care in the acute paediatric setting: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(2), 361–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13178

- Dissanayake, E. (2009). Root, leaf, blossom, or bole: Concerning the origin and adaptive function of music. In S. Malloch & C. Trevarthen (Eds.), Communicativemusicality: Exploring the basis of human companionship (pp. 17–30). USA: Oxford University Press.

- Edwards, J. (2014). The role of the music therapist in promoting parent-infant attachment/Favoriser l’attachement parent-enfant: Role du musicothérapeute. Canadian Journal of Music Therapy, 20(1), 38–48. http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30073430

- Ettenberger, M., & Ardila, Y. M. B. (2018). Music therapy song writing with mothers of preterm babies in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)–A mixed-methods pilot study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 58, 1–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2018.03.001

- Fancourt, D., & Perkins, R. (2018). The effects of mother–infant singing on emotional closeness, affect, anxiety, and stress hormones. Music & Science, 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2059204317745746

- Feldman, R. (2009). The development of regulatory functions from birth to 5 years: Insights from premature infants. Child Development, 80(2), 544–561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01278.x

- Fevang, S. K. E., Hysing, M., Markestad, T., & Sommerfelt, K. (2016). Mental health in children born extremely preterm without severe neurodevelopmental disabilities. Pediatrics, 137(4), e20153002. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3002

- Field, T. (2010). Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behavior & Development, 33(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.005

- Filippa, M., Menin, D., Panebianco, R., Monaci, M. G., Dondi, M., & Grandjean, D. (2020, June). Live maternal speech and singing increase self-touch and eye-opening in preterm newborns: A preliminary study. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 44(4), 453–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-020-00336-0

- Filippa, M., Panza, C., Ferrari, F., Frassoldati, R., Kuhn, P., Balduzzi, S., & D’Amico, R. (2017). Systematic review of maternal voice interventions demonstrates increased stability in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica, 106(8), 1220–1229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13832

- Flacking, R., Lehtonen, L., Thomson, G., Axelin, A., Ahlqvist, S., Moran, V. H., Ewald, U., & Dykes, F. (2012). Closeness and separation in neonatal intensive care. Acta Paediatrica, 101(10), 1032–1037. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02787.x

- Ghetti, C., Bieleninik, Ł., Hysing, M., Kvestad, I., Assmus, J., Romeo, R., Ettenberger, M., Arnon, S., Vederhus, B. J., Gaden, T. S., & Gold, C. (2019). Longitudinal study of music therapy’s effectiveness for premature infants and their caregivers (LongSTEP): Protocol for an international randomised trial. BMJ Open, 9(8), e025062. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025062

- Ghetti, C. M., Vederhus, B. J., Gaden, T. S., Brenner, A. K., Bieleninik, Ł., Kvestad, I., Assmus, J., & Gold, C. (2021). Longitudinal study of music therapy’s effectiveness for premature infants and their caregivers (LongSTEP): Feasibility study with a Norwegian cohort. Journal of Music Therapy, 1–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thaa023

- Gooding, J. S., Cooper, L. G., Blaine, A. I., Franck, L. S., Howse, J. L., & Berns, S. D. (2011). Family support and family-centered care in the neonatal intensive care unit: Origins, advances, impact. Seminars in Perinatology, 35(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semperi.2010.10.004

- Graven, S. N., & Browne, J. V. (2008). Auditory development in the fetus and infant. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, 8(4), 187–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2008.10.010

- Harrison, H. (1993). The principles for family-centered neonatal care. Pediatrics, 92(5), 643–650. http://intl-pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/92/5/643

- Haslbeck, F. B. (2014). The interactive potential of creative music therapy with premature infants and their parents: A qualitative analysis. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 23(1), 36–70. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2013.790918

- Haslbeck, F. B., & Bassler, D. (2020). Clinical practice protocol of creative music therapy for preterm infants and their parents in the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 155, e60412.

- Hepper, P. G., & Shahidullah, B. S. (1994). Development of fetal hearing. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 71(2), F81–F87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/fn.71.2.F81

- Hill, S., Engle, S., Jorgensen, J., Kralik, A., & Whitman, K. (2005). Effects of facilitated tucking during routine care of infants born preterm. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 17(2), 158–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pep.0000163097.38957.ec

- Hunter, J. (2010). Therapeutic positioning: Neuromotor, physiologic, and sleep implications. In M. J. Kenner (Ed.), Developmental care of newborns and infants. A guide for health professionals (2nd ed.) (pp. 283–312). Mosby.

- Hutchfield, K. (1999). Family‐centred care: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29(5), 1178–1187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00987.x

- Jobe, A. H. (2014). A risk of sensory deprivation in the neonatal intensive care unit. The Journal of Pediatrics, 164(6), 1265–1267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.072

- Johnson, B. H. (2000). Family-centered care: Four decades of progress. Families, Systems, & Health, 18(2), 137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091843

- Jolley, J., & Shields, L. (2009). The evolution of family-centered care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24(2), 164–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2008.03.010

- Kokorelias, K. M., Gignac, M. A., Naglie, G., & Cameron, J. I. (2019). Towards a universal model of family centered care: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 564. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4394-5

- Korja, R., Savonlahti, E., Ahlqvist‐Björkroth, S., Stolt, S., Haataja, L., Lapinleimu, H., Piha, J., Lehtonen, L., & Group, P. S. (2008). Maternal depression is associated with mother–infant interaction in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica, 97(6), 724–730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00733.x

- Lasiuk, G. C., Comeau, T., & Newburn-Cook, C. (2013). Unexpected: An interpretive description of parental traumas’ associated with preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 13(S1), S13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-13-S1-S13

- Lawlor, M. C., & Mattingly, C. F. (1998). The complexities embedded in family-centered care. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 52(4), 259–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.52.4.259

- Leach, P. (2017). Transforming infant wellbeing: Research, policy and practice for the first 1001 critical days. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315452890

- Leadsom, A., Field, F., Burstow, P., & Lucas, C. (2013). The 1001 critical days: The importance of the conception to age two period. A Cross-Party Manifesto. Parent-infant Foundation. https://www.nwcscnsenate.nhs.uk/files/8614/7325/1138/1001cdmanifesto.pdf

- Lee, G. Y., & Kisilevsky, B. S. (2014). Fetuses respond to father’s voice but prefer mother’s voice after birth. Developmental Psychobiology, 56(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21084

- Loewy, J. V. (2015). NICU music therapy: Song of kin as critical lullaby in research and practice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1337(1), 178–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12648

- Loewy, J. V. (2016). First sounds: Rhythm, breath, lullaby trainer compendium. Satchnote Armstrong Press.

- Loewy, J. V., Stewart, K., Dassler, A. M., Telsey, A., & Homel, P. (2013, May). The effects of music therapy on vital signs, feeding, and sleep in premature infants. Pediatrics, 131 (5), 902–918. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1367

- MacKean, G. L., Thurston, W. E., & Scott, C. M. (2005). Bridging the divide between families and health professionals’ perspectives on family‐centred care. Health Expectations, 8(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2005.00319.x

- Malloch, S., & Trevarthen, C. (2009). Musicality: Communicating the vitality and interests of life. In S. Malloch & C. Trevarthen (Eds.), Communicative musicality: Exploring the basis of human companionship (Vol. 1, pp. 1–10). Oxford University Press.

- Malloch, S. N. (1999). Mothers and infants and communicative musicality. Musicæ Scientiæ, 3(1_suppl), 29–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/10298649000030S104

- McLean, E. (2016a). Exploring parents’ experiences and perceptions of singing and using their voice with their baby in a neonatal unit: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Qualitative Inquiries in Music Therapy, 11, 1–42. https://www.barcelonapublishers.com/resources/QIMT11/McLean_Parents_Experiences.pdf

- McLean, E. (2016b). Fostering intimacy through musical beginnings: Exploring the application of communicative musicality through the musical experience of parents in a neonatal intensive care unit. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy, 16(2). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15845/voices.v16i2.874

- McLean, E., McFerran, S. K., & Thompson, G. A. (2018). Parents’ musical engagement with their baby in the neonatal unit to support emerging parental identity: A grounded theory study. J. Neonatal Nurs, 24(4), 203–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2018.09.005

- Misund, A. R., Nerdrum, P., Bråten, S., Pripp, A. H., & Diseth, T. H. (2013). Long-term risk of mental health problems in women experiencing preterm birth: A longitudinal study of 29 mothers. Annals of General Psychiatry, 12(1), 33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-12-33

- Mondanaro, J. F., Ettenberger, M., & Park, L. (2016). Mars rising: Music therapy and the increasing presence of fathers in the NICU. Music and Medicine, 8(3), 96–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.47513/mmd.v8i3.440

- Moon, C. (2011). The role of early auditory development in attachment and communication. Clinics in Perinatology, 38(4), 657–669. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2011.08.009

- Muller-Nix, C., Forcada-Guex, M., Pierrehumbert, B., Jaunin, L., Borghini, A., & Ansermet, F. (2004). Prematurity, maternal stress and mother–child interactions. Early Human Development, 79(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2004.05.002

- Murray, D. W., Rosanbalm, K., Christopoulos, C., & Hamoudi, A. (2015). Self-regulation and toxic stress: Foundations for understanding self-regulation from an applied developmental perspective. Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/report_1_foundations_paper_final_012715_submitted_508.pdf

- Nakata, T., & Trehub, S. E. (2011). Expressive timing and dynamics in infant-directed and non-infant-directed singing. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind and Brain, 21(1–2), 45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094003

- NOBAB. (2002). Nordic standard for care of children and adolescents in hospital. Nordic Network for Children's Rights and Needs in Health Care.

- Nöcker-Ribaupierre, M. (2013). Premature infants. In J. Bradt (Ed.) Guidelines for music therapy practice in pediatric care (pp. 66-104). Gilsum, NH: Barcelona.

- Nugent, J. K., Keefer, C. H., Minear, S., Johnson, L. C., & Blanchard, Y. (2007). Understanding newborn behavior and early relationships: The newborn behavioral observations (NBO) system handbook. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Papoušek, H. (1996). Musicality in infancy research: Biological and cultural origins of early musicality. In I. Deliège & J. Sloboda (Eds.) Musical Beginnings: Origins and Development of Musical Competence (pp. 37-85). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198523321.001.0001

- Papoušek, M., Papoušek, H., & Symmes, D. (1991). The meanings of melodies in motherese in tone and stress languages. Infant Behavior & Development, 14(4), 415–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-6383(91)90031-M

- Puthussery, S., Chutiyami, M., Tseng, P.-C., Kilby, L., & Kapadia, J. (2018). Effectiveness of early intervention programs for parents of preterm infants: A meta-review of systematic reviews. BMC Pediatrics, 18(1), 223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1205-9

- Raiskila, S., Lehtonen, L., Tandberg, B. S., Normann, E., Ewald, U., Caballero, S., Varendi, H., Toome, L., Nordhøv, M., Hallberg, B., Westrup, B., Montirosso, R., & Axelin, A. (2016). Parent and nurse perceptions on the quality of family-centred care in 11 European NICUs. Australian Critical Care, 29(4), 201–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2016.09.003

- Rauh, V. A., Achenbach, T. M., Nurcombe, B., Howell, C. T., & Teti, D. M. (1988). Minimizing adverse effects of low birthweight: Four-year results of an early intervention program. Child Development, 59(3), 544–553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1130556