ABSTRACT

Introduction

Music therapy is actively used with early adolescents in relation to their emotional skill development. Yet, the conceptualization of emotional skills is typically not systematically addressed in therapeutic practice. This study examined music therapists’ views on the progress of emotional skills when working with early adolescents with mental health conditions. The study also explored what kind of methods the therapists use with the target group, and the applicability of a previously published conceptual model.

Method

We conducted a deductive-inductive content analysis of transcripts from four focus group interviews among 13 professional music therapists.

Results

The therapists concluded that the progress of the emotional skills of their clients can be seen both in daily functioning as well as the client’s functioning in therapy. The selection of therapy methods was broad and included both music-based and non-music-based methods. Therapists considered the presented conceptualization of emotional skills to be valid, but had difficulty examining their practices using all levels of the model. Several practical features were identified that were considered beneficial for the therapists in clinical practice.

Discussion

This study adds to knowledge about the progress of emotional skill development, working methods, and useful perspectives for working on emotional skills in early adolescents with mental health conditions. The conceptual model of emotional skills can offer a tool for helping music therapists define, observe and analyse emotional skills in the therapy context.

Introduction

Early adolescents (approximate age 11–13 years) are in the middle of many biological, cognitive, and socio-emotional changes (Salmela-Aro & Levesque, Citation2011; Sawyer et al., Citation2012). Mentally, early adolescents start to be more proactive, more able to self-regulate and more self-reflective (Bandura, Citation2018). They start to solve more abstract problems, develop hypotheses, and are able to consider consequences of different hypotheses (Carr, Citation2015). However, many early adolescents struggle with the balanced development from childhood to adolescence and have mental health conditions.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 20 per cent of children and adolescents have mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, behavioural disorders, and developmental disabilities, and these conditions are the major causes of illness and disability among young people (10–19 years) (World Health Organization, Citation2021). WHO (2021) estimates that half of all mental health conditions start by the age of 14 years. Therefore, early adolescence is a particularly meaningful time to focus on mental health. Mental health conditions have diverse effects in early adolescents’ life, such as difficulties in schoolwork, school absences, and use of intoxicants (WHO, Citation2021; Zins et al., Citation2006). Early adolescents’ mental health conditions are often related to a lack of emotional and interaction skills (Gonçalves et al., Citation2019; Parker et al., Citation2006).

Emotional skills of early adolescents

Emotional and interaction skills generally include how people understand emotions of their own or others, how they express their internal states, needs, and desires and how they manage emotional and social life situations (Malti & Cheah, Citation2021). During early adolescence, the development of emotional and interaction skills is associated with greater emotional reactivity, individuals’ ability to reflect more on emotions and assess the acceptability and expression of emotions, and to develop strategies to manage emotions in a new way (Davey et al., Citation2008; Steinberg, Citation2005).

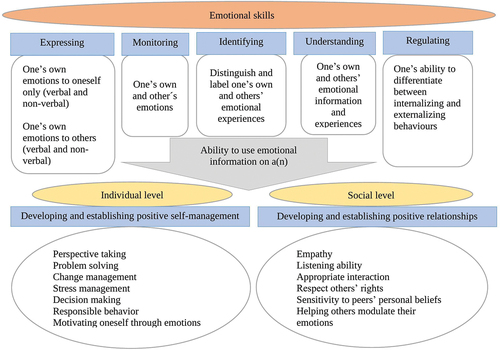

In scientific literature, the practical and detailed definition of the term “emotional skills” has been unclear, and many overlapping terms have been used inconsistently (Humphrey et al., Citation2007; Matthews et al., Citation2002; Wigelsworth et al., Citation2010). There are also differences in whether the emotional skills are approached as merely emotional (e.g. Saarni, Citation1999) or as a combination of social and emotional skills (e.g. Denham et al., Citation2003, Citation2012). When Salokivi et al. (Citation2021) conducted a scoping review to define the term “emotional skills” in the context of early adolescence, they found 15 different emotional skills-related key terms from the scientific literature. They originally chose the term “emotional skills” because it is a generic term that is used daily in Finland by medical, rehabilitation, and educational professionals. Finally, based on the results of the scoping review and a conceptual analysis of terms related to emotional skills, they identified six components of emotional skills in early adolescents: (a) expressing, (b) monitoring, (c) identifying, (d) understanding, (e) regulating emotions, and (f) the ability to use emotional information (i.e. implication component). The implication component is composed of two parts: (a) the ability to use emotional information on an individual level for developing and establishing positive self-management, and (b) the ability to use emotional information on a social level for developing and establishing positive relationships (Salokivi et al., Citation2021). The developed conceptual model (a conceptual model is an idea or concept presented in the form of a diagram or other illustration [Corsini, Citation2016]) highlights the different components of emotional skills, but does not highlight the order of development of the skills or the relationships between the components. Salokivi’s et al. (Citation2021) conceptual model of emotional skills in early adolescents serves as the framework for this study. The model is presented in .

Figure 1. Components of early adolescents’ emotional skills (Salokivi et al., Citation2021).

Music therapy among early adolescents with mental health conditions

In Finland, children and adolescents are the largest client group in music therapy, and most of them have mental health conditions (Social Insurance Institution of Finland, Citation2020). They have behavioural problems, difficulties in emotional regulation, fears, challenging life situations, or low self-esteem (Finnish Society for Music Therapy, Citation2021). Research on the effectiveness of music therapy as a treatment for early adolescents (11–14 yrs.) with mental health conditions is relatively limited, but a few studies have reported many beneficial effects. Music therapy can reduce anxiety (Hendricks et al., Citation1999) and depression (Chen et al., Citation2019), influence mood state (Shuman et al., Citation2016), increase emotional responsiveness (Wasserman, Citation1972), reduce impulsiveness and increase self-regulation (Layman et al., Citation2002; Uhlig et al., Citation2018) and assist in developing a self-image (Friedlander, Citation1994). Gold et al. (Citation2004) published a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of music therapy in the treatment of children and adolescents with psychopathological problems. The analysis showed that music therapy had a significant, medium or large effect on health. The analysis did not disaggregate the impact of music therapy by age group in children and adolescents, so the study does not highlight the impact of therapy on early adolescents in particular.

Music therapy methods in use for early adolescents with mental health conditions

Music therapy methods used in music therapy for early adolescents with mental health conditions have not been systematically studied. However, music therapy methods among early adolescents in general have been categorized into the following domains: live songs (choosing, singing, playing, and writing), improvisation (instrumental and vocal), pre-recorded music (listening, discussion, and relaxation), and musical games (McFerran, Citation2010). These methods can be further categorized into receptive and active methods. In receptive methods, the client listens to pre-recorded or live performed music, and in active methods clients create music through voice, instruments, or song writing (Geipel et al., Citation2018). These methods vary depending on the therapist’s orientation and the client’s interests.

When considering the studies that have reported positive effects of music therapy among early adolescents (11–14 yrs.), both receptive and active methods have been used. Methods include music listening (Chen et al., Citation2019; Gold et al., Citation2017; Layman et al., Citation2002; Shuman et al., Citation2016), improvisation (Gold et al., Citation2017; Shuman et al., Citation2016), singing and rapping (Chen et al., Citation2019; Uhlig et al., Citation2018) and playing many kinds of instruments (Layman et al., Citation2002; Shuman et al., Citation2016).

Promotion of early adolescents’ emotional skills is an essential component of the music therapist’s work. Since early adolescents are the largest client group served by music therapists in Finland, research on this topic is of practical relevance. It is also justified to focus the research specifically on early adolescents rather than on adolescents in general. The age range of young people is wide, from 10 to 19 years (WHO, Citation2021), and studies have shown differences, for example, in emotional regulation between age groups (Zimmermann & Iwanski, Citation2014). In music therapy, it is important to identify the early adolescents’ emotional skills and any changes or progress in them. It should be possible to monitor progress systematically. However, research on this topic is scattered and no studies have presented a compendium, e.g. a conceptual model, which summarizes emotional skills. There are also no studies on what indicators of progress in emotional skills music therapists monitor or what methods they use in their work to develop emotional skills in early adolescents.

Study objectives

This study investigated Finnish music therapists’ views on the progress of emotional skill development in music therapy for early adolescents with mental health conditions. Additionally, the study explored what kind of therapeutic methods music therapists use with the target group. The study also investigated the applicability of the conceptual model of emotional skills in early adolescents (Salokivi et al., Citation2021) to the clinical practice of music therapy.

Methods

The authors used focus group interviews and a deductive-inductive content analysis study design for exploring the music therapists’ experiences and perceptions.

Rationale for study design

The focus group interview enables in-depth discussion even if the number of participants is relatively small; it helps to understand what and how people think about a specific area of interest, and it also enables interaction between the participants (Barbour, Citation2007). Interaction between informants helps to explore and clarify participants’ perspectives, experiences, concerns and needs, and also helps informants to challenge their perspectives (Kitzinger & Holloway, Citation2005; Liamputtong, Citation2011).

Participants

Music therapists with at least five years of working experience were recruited using a Webropol internet questionnaire (version 31.07.2020 MPO; Webropol, Citation2020). At least five years of clinical experience was considered necessary to understand the development of emotional skills during the therapy process. Webropol – questionnaire was distributed among all professional members (227) of the Finnish Society of Music Therapy in August 2020. Webropol is a web-based survey and reporting tool. Music therapists who work with early adolescents were asked to answer the questionnaire about diagnostic client groups they work with, duration of working experience and the willingness to participate in a focus group interview. The study’s fact sheet and data protection notification were attached. One reminder about the questionnaire was sent. The questionnaires were conducted anonymously. After a reminder, 33 music therapists answered the questionnaire and 13 therapists were willing to participate in focus group interviews. Participants were of different genders, different age groups, with varying lengths of work experience. Most of the participants worked as private music therapists, as is often the case in Finland. They also worked in different geographical areas of Finland. All participants were of Finnish background. Participants who consented to the focus group interview provided their contact details and in return received the focus group interview questions, a survey fact sheet and a privacy notice in relation to the focus group interview.

Setting

Four video-recorded focus groups were organized as online video-meetings in August 2020, due to geographical distances and restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Four groups were considered sufficient because studies show that 80% of new knowledge is gained after two or three focus groups (Guest et al., Citation2017).

The number of the participants in groups varied between two and five. The maximum group size of five members was set beforehand because such a group size allows participants to be active members of the discussion and to explore the issues in detail (Liamputtong, Citation2011; Smithson et al., Citation2008). One group included only two members because of a last-minute cancellation. The three other groups had three to five members. No one else was present in the focus group meetings besides the participants and the researcher.

Focus group interviews

The focus group interviews were semi-structured, which provided an opportunity to focus the discussion on predetermined theoretical issues, but also allowed for new insights to emerge if they were generated by the focus groups (Brinkmann, Citation2013). The interview was divided into four main questions based on the research questions: (a) Where do you see the progress of emotional skills in music-based functioning? (b) Where do you see the progress of emotional skills in non-music-based functioning? (c) What music-based methods do you use when you are working on emotional skills? (d) What non-music-based methods do you use when you are working on emotional skills? All four questions contained five sub-questions based on the components of emotional skills (Salokivi et al., Citation2021) (see ). Focus group interview questions are presented in Supplementary Material 1.

The implication component of emotional skills “ability to use emotional information” was not included in the questions because of its broad content. It would have expanded the set of questions, and the focus group interviews’ time limit would have been exceeded. The original English-language components of the emotional skills were translated into Finnish. Commonly used terms in Finnish were used in the translation. The translation was largely based on a suggestion from the translation app DeepL (DeepL GmbH, Citation2017). The translation application DeepL is an AI-based application that uses artificial neural networks. All the focus group interviews were video recorded completely and transcribed verbatim manually.

The applicability of the emotional skills domains to music therapy practice was assessed on the basis of the focus group interview data. Interviewees had been given the emotional skills components to familiarize themselves with beforehand. At the beginning of the interviews, the conceptual model was verbally outlined to the interviewees, the purpose of the study was explained, and the interviewees were given the opportunity to ask follow-up questions before the interviews began. These discussions and the data from the focus group interviews were used to explore how the participants applied the emotional skills components in their music therapy practice.

The first author, who acted as moderator/interviewer, was a doctoral researcher and had previous experience with focus group interviewing. She had worked several years as a music therapist and was very familiar with the subject of the study. She had met most of the participants previously in other professional contexts. The interviewer’s role was to ask the pre-determined set of questions, moderate the discussion if needed, take care of more reticent participants’ engagement, follow the saturation of the discussion within one question, and lead the interview forward within the time limit. The time limit was 1.5–2 hours, depending on the group size (Liamputtong, Citation2011).

Ethical considerations

The study received approval from the Human Sciences Ethics Committee of University of Jyväskylä (Number: 746/13.00.04.00/2020). The first Webropol survey was conducted anonymously with the study’s fact sheet and data protection notification. Participants received the study’s fact sheet, data protection notification, and an informed consent form. Data were saved in two separate hard disks with a secure login. The researcher who was an interviewer was the only person who handled the focus group data before anonymization. The participants were not identifiable in the transcriptions or the research report.

Deductive-inductive content analysis

The qualitative content analysis was conducted using a deductive approach, applying the components of emotional skills (see ) as a conceptual starting point, but also using an inductive analysis method, which allowed the participants’ experiences of working methods in therapy and progress in emotional skill development to be described (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). The first author of the study conducted the analysis. The starting point for coding was the four main domains and 20 sub-domains presented as part of the research questions (a, b, c, d) and openness for new domains. Coding was accomplished with Atlas.ti, version 8.4.5 (Citation2019). Atlas.ti is a qualitative data analysis and research software program that enables the researcher to move forward and backward in the data and structure text and organize domains, codes and quotes.

The first coding round produced four main domains, 36 sub-domains and 194 codes. After analyzing the gathered information, domains and codes were particularized. At the end, the process produced five main domains, 27 sub-domains and 132 codes (main codes and sub-domains are presented in supplementary materials). One new domain was: useful perspectives for working on emotional skills in early adolescents with mental health conditions. Main domains and sub-domains, after analyzing focus group interview, are presented in Supplementary Material 2.

A second researcher (the fourth author of this study) reviewed all the main domains, sub-domains and the result of coding. At a later stage of the analysis, he reviewed the coding again and how the results of the coding were reported. Throughout the deductive and inductive analysis, the first and last authors were in constant dialogue, and all members of the research team held regular meetings on the progress of the analysis (Elo et al., Citation2014). In addition, the first author, who conducted the analysis, wrote a memo on the steps of the analysis process. shows the steps of the deductive-inductive content analysis in this study to give the reader an idea of the process.

Table 1. Deductive-inductive content analysis process in this study.

Results

The findings of the study are grouped into four main categories, three based on the three main aims of the study (indicators of progress in emotional skill development, methods used, and applicability of the conceptual model to clinical practice) and a fourth based on the perspectives that the content analysis highlights as useful for music therapists.

Progress of emotional skill development in music-based and non-music based functioning

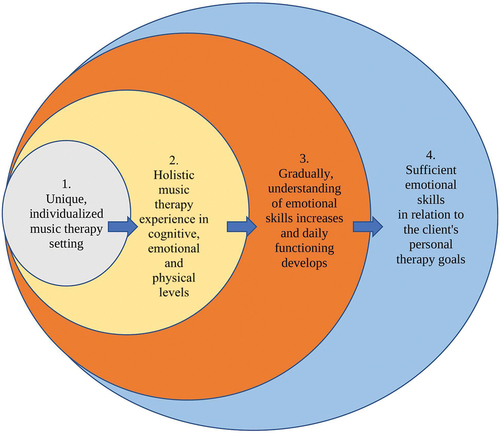

Participants described the development of emotional skills as a multi-level and holistic experience. Music therapy provides cognitive, emotional and physical experiences through music-based and non-music-based methods. Gradually, the client achieves an understanding of emotional skills, which progressively leads to desirable changes in daily function. This process is illustrated in .

Progress in music-based functioning

The progress in emotional expression was reflected in a general increase in listening and playing music, but also in a gradual increase in personal content in self-composed songs and music. In addition, the client’s expression became more versatile and courageous. Interviewee H describes: “Changes happen in rhythm, tone, and volume, and often the music becomes more melodic.”

In emotional regulating, progress was seen in an increase of structured musical expressing and functioning, and in being able to concentrate on working for a longer time. Interviewee J states:

It goes from chaos to containment. The starting point is often quite a mess. When the client can play a basic beat with drums, it is possible to play, for example, faster or slower and then it is possible to take control of both the music and the emotions it conveys.

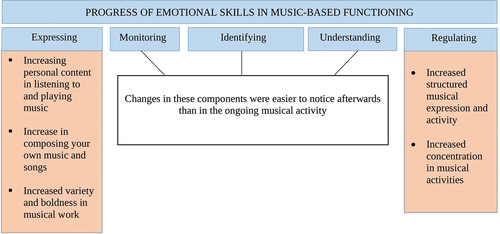

Progress in other areas of emotional skills, monitoring emotions, identifying emotions, and understanding emotions, were considered to be areas where progress was easier to see in retrospect, not necessarily in ongoing musical activities. In general, many interviewees described that often at the beginning of the process their clients want to use existing, composed music and songs. Then, when the client feels comfortable enough, they may start to improvise, write songs and compose music. Interviewee C commented: “At first I use existing songs or melodies, which gives a feeling of security. Improvisation can be so revealing, and I think on some level young people understand it.” The progression of emotional skills in music-based activities is shown in .

Progress in non-music-based functioning

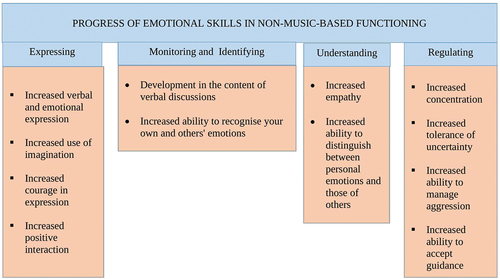

In non-music-based functioning, progress in emotional expression and emotion regulation was the easiest for participants to describe. Progress in emotional expression was reflected in increased verbal and other emotional expression, as well as in the ability to analyse one’s own experiences. Personal content in therapy work both increased and deepened. Interviewee G stated: “The client is more courageous in expressing himself, more relaxed and more confident in the therapy situation. If there are some difficult situations, the client is willing to start exploring them and is able to be in those feelings. “

The client no longer negates or avoids exploring difficult issues. The use of imagination increased, the clients were braver in general, and an interaction was experienced to be more positive. Interviewees reported that sometimes towards the end of the therapy process, music-based methods were not used at all and verbal discussions were the main method of intervention.

In emotional regulating within non-music-based functioning, progress was seen in the ability to concentrate more, tolerate uncertainty and disappointments, be more present in the situation and interaction, manage aggression, and accept guidance for their functioning. The therapy situation was more peaceful in its entirety.

The progress in the components emotional monitoring, emotional identifying and emotional understanding could be seen in the content of verbal discussions and in the client’s ability to recognize their own emotions and those of others. When emotional understanding develops further, an ability to empathize increases and it is easier to distinguish one’s own emotions from those of others. Interviewee J described the change in interaction:”It is most important that you are able to listen … the music, the therapist … The clients start to consider … . When you develop in listening, you can identify, regulate, and understand these things.”

The indicators of progress of emotional skill development in non-music-based functioning is presented in .

General progress, without being categorized under specific areas of emotional skills, was reflected in many ways in non-music-based work. The client commits to therapy, was able to make independent choices and share important moments with the therapist more often and was more skilful in steering one’s own functioning. In addition, the clients were more interested in their life in general, their self-esteem was better, and social skills developed positively both in and out of therapy. In addition, the clients’ social roles were better balanced, as was feedback from outside therapy. The therapists interviewed had experienced that it was quite typical at the beginning of therapy that feedback from the client could vary in different social contexts and could be contradictory. Gradually, the feedback became more consistent as the therapy process progressed. The therapists described all these positive changes mentioned above as the result of emotional integration.

Music-based and non-music-based therapy methods

Participants worked with a wide range of methods on all the emotional skills. In most cases, the methods were not targeted at a specific component of the emotional skills.

Music-based methods

Participants worked in the forms of playing, singing, and listening to music. Playing and singing could occur with improvised music, precomposed music, or the songs the client composed in the therapy. Listening to music could entail listening to existing recordings or recordings of the client’s own improvisation or singing. Participants described how listening to the client’s recordings provided an opportunity to delve deeper into the meanings the client gave to the music; inner expression was tangible and could be explored from a distance. Interviewee H described how both improvisation and finished compositions enabled work on emotional skills such as monitoring and identifying: “Improvisation is a good example of how it happens: it is a process that happens as improvisation progresses. I think it’s quite natural to follow the emotions in a piece of music and then identify those emotions.”

This study was conducted among Finnish music therapists and some locally developed methods were mentioned as being very typical. These methods were Figurenotes (Kaikkonen et al., Citation2016) and Storycomposing (Hakomäki, Citation2020). Both can be used in composing, playing, and singing. In Figurenotes, the notation is very concrete, and the notes are marked with colours and shapes. Notation includes all the necessary musical information, such as rests, pitches and octaves (Kaikkonen et al., Citation2016). Storycomposing is a model of musical interaction that provides a means of expressing experiences and emotions. The client’s musical creation is notated using Figurenotes, which allows the content of the musical creation to be reviewed afterwards. The musical creation is also presented to a selected group of people (Hakomäki, Citation2020).

When working with emotion regulation skills, participants emphasized the use of musical structure and learning. Through motivational music training, clients gain a multi-level experience of emotion regulation on a mental, physical, and cognitive level. The structure of music provides a ready-made framework for this. Participants also felt that musical interaction in general was a good way to practice regulation. Interviewee I reflected on this aspect: “Regulation happens in the interaction between us, the client starts to understand that we are doing this together, and it makes sense to listen and adjust one’s own playing to match the other’s music in a reciprocal way.”

Non-music-based methods

Participants used many other methods besides music without setting them under certain emotional skills’ component. Therapists use, for example, plays, board games, computer games, puppet theatre, and drama. These were used together with music but also separately. Interviewee L told about drama and puppet theatre:

I use a lot of drama and a puppet theatre; it gives a possibility to get distance from the emotions and explore them. Often, emotions are already in the playing even if the client is not recognizing them yet in oneself.

Additionally, storytelling, painting, drawing, filmmaking, and cards with the emotion-related pictures were used. Interviewee D described this kind of cards:

If the clients’ emotional expression is difficult and scanty, I may ask them to choose a card. Then we start to explore how we could play or draw the emotion, or we find a song that would reflect it somehow. This often works well, and we can start to talk about the emotions or play music based on a certain feeling.

Photography, family portraits, physical expression, dance and relaxation techniques were used. Vibroacoustic and physioacoustic methods were also mentioned as part of therapy as a physical way of dealing with different experiences. In the area of regulation, participants discussed the ability to manage stress and how to teach concrete ways to do so. Interviewee M described, “I try to get the client to notice where in their body they feel a certain emotion. I also teach how to release anxiety or tension from the body, for example. I teach stress management and relaxation management.” Participants mentioned that in stress management, the client needed many more emotional skills than just regulation, such as monitoring, identifying, and understanding.

Playing games was also mentioned as a way of regulating emotions. Participants described that games were often motivating and appealing to clients, and that they allowed them to practice emotion regulation and learn to tolerate disappointment and frustration. In addition, one participant described how to make use of YouTube videos that the client brings to therapy. The participant felt that the videos provided opportunities to monitor and identify emotions and allowed for an understanding of the client’s personal interests. The participant sought to extract emotional content from the videos and direct the client’s attention to emotionally important themes in the videos.

All interviewees felt that oral discussion was an important part of the music therapy process. Verbal discussion can be associated with other methods, but sometimes it is the main method depending on the client’s choice. However, verbal discussion can be difficult for some clients and sometimes their emotional vocabulary may be limited. Part of the therapeutic work may involve expanding the vocabulary so that the client can express emotions more effectively. Verbal discussion opens up the possibility of exploring feelings afterwards. Overall, versatile interaction skills were perceived as important, as interviewee M stated, “Clients need musical expression, but also words and pictures. Improving all kinds of communication skills is one of the main goals of my work.”

Applicability of the conceptual model of the components of emotional skills in music therapy practice

Therapists were not used to analyzing emotional skills in as much detail as the way they are categorized in the components. Participants described well how to work with the regulation and expression of emotional skills and how these skills progressed. Participants had difficulty analyzing progress in other emotional skills. Participants identified the other components and understood their content, but found it difficult to identify a specific moment when identifying, monitoring or understanding emotions occurred in practice. They felt that these skills could be observed retrospectively in the progress of the client’s daily functioning, rather than, for example, in an ongoing musical moment.

Useful perspectives for working on emotional skills in early adolescents with mental health conditions

Participants pointed out that early adolescents often want to control the therapy situation, and their desire to avoid dealing with emotions can be strong at the beginning. Interviewees stressed that this avoidance is a kind of precondition. Interviewee H described this stage: “With early adolescents, it is important that they tolerate emotions… tolerate the tension that comes with emotions … so that they can be there, in those situations.”

Participants stated that modelling and mirroring are workable methods in therapy. Participants model and mirror the emotional contents in music and in discussion with the emotional and verbally unsure early adolescents. For example, in discussion this can happen by presenting reflective questions, such as what interviewee M stated: “I may say that: Somehow, I think that this music may tell about these kinds of feelings, what do you think about it, could it be so or do you think that I’m wrong?” Participants stated that it is important to increase the emotional vocabulary of the client through these kinds of reflective questions.

In general, participants stressed the importance of a positive working atmosphere where clients can experience success and acceptance. They emphasized playfulness and humour as a working attitude of the therapist. Therapists avoided imposing strict rules on the therapy situation, only the necessary rules, such as not harming oneself, the therapist or the equipment.

Participants highlighted strongly the importance of a family-centred working approach. The early adolescents with mental health conditions are often wounded in their family relationships, and it can take time before they are ready to trust the therapist. Participants stated that an interaction with the therapist should offer a substitutive experience for the client. The training and practice of emotional skills takes place first in the therapeutic relationship, then elsewhere. However, early adolescents spend most of their time in their families and often the guardians have similar types of problems with interactions and emotional skills. It is important that when new skills are learned in therapy, the guardians are also ready to support and develop their own emotional and interaction skills. Interviewee B pondered: “It is important that guardians understand that therapy is looking for the change and this change will need guardians’ support, even it is not necessarily easy for them. They are the enablers of the change.”

Participants also gave their views on how to help therapists to cope with their work in emotional therapy. Because of the intensity of the therapy work and its emotional strain, the participants said that self-reflecting on the transference feelings and having regular clinical supervision were crucial for the therapist’s own well-being. Clinical supervision helps to observe the therapy situations afterwards and allows for new viewpoints from the supervisor.

Participants also discussed the possibility of terminating therapy. When are the emotional skills sufficient? In general, it is obvious that developing emotional skills continues throughout an individual’s life. The interviewee therapists stated that feedback from outside of therapy played a crucial role in indicating a positive progress in emotional skills. They emphasized the importance of discussions with guardians and teachers about how the client applied the emotional skills at home and at school. In addition, a client’s self-evaluation and the therapist’s impression and experience of working with the client provided additional information.

Discussion

Progress of emotional skill development in music therapy

This study describes the progress of emotional skill development in music therapy as a multi-level and holistic process that encompasses the mental, physical and cognitive levels (see ). The client’s ability to function in daily life was the main indicator of progress. Progress in emotional skill development was identified as an outcome of “emotional integration”. Emotional integration seems to be the same as the theoretical term “affect integration”. Affect integration is defined as an essential component of mental health that encompasses the functional integration of affect, cognition, and behaviour (Solbakken et al., Citation2011). It refers to the ability to use the adaptive properties of distinct affect in personal adjustment (Taarvig et al., Citation2015). Many psychotherapeutic approaches highlight the integration of affect, cognition and behaviour as the main area of therapeutic progress (Solbakken et al., Citation2011).

Participants described many beneficial effects of music therapy, especially in the emotional skills expressing and regulating (see ). Also, for example, Montello and Coons (Citation1998) and Patterson et al. (Citation2015) have reported that music therapy facilitates self-expression among early adolescents and adolescents with mental health conditions. Layman et al. (Citation2002) and Uhlig et al. (Citation2018) have reported reduced impulsivity and increased self-regulation.

The study presents a point of view that the possibility of using improvisation, song writing, and composing with the early adolescent might sometimes be one indicator of progress. The possibility to work with these methods may reflect an increased sense of safety and trust in the therapy process and the client’s readiness to go deeper into personal contents.

Methods for developing emotional skills in early adolescents

All possible music-based and non-music-based methods are in use both simultaneously and separately. Both musical and verbal work are essential. This study supports the idea that an eclectic approach is best practice when working on emotional skills for early adolescents with mental health conditions (Gold et al., Citation2004; McFerran, Citation2010). The multimethod eclectic approach means that techniques from different models or theories are mixed and the therapist chooses from a variety of music therapy techniques to meet individual client’s needs (Gold et al., Citation2004).

On the basis of this study, it is not possible to target specific working methods to a particular area of emotional skills. However, in the regulating component, participants emphasized using more musical structure and learning. The structural element of music offered a natural multilevel (mental, physical, and cognitive) working base for training regulating.

Applicability of the conceptual model of the components of emotional skills in music therapy practice

Based on the impression from the focus group interview data, the professionals interviewed in this study accepted the emotional skills components (see ) as framework for analyzing emotional skills, however, as explained in this article, they experienced challenges in responding in it. The conceptual model was new, and the therapists were not used to analyzing the emotional skills-related therapy work in such detail. Based on these data, working with the regulating and expressing components are at the very core of emotional skills-related music therapy work and professionals are most aware of how to work with these components and follow the progress.

In most cases, participants in focus group interviews discussed all components of emotional skills simultaneously, even when asked about a specific component. This finding may reflect the holistic nature of music therapy work, but it may also reflect the therapists’ clinical style of analysis and decision making. Applying clinical decision-making in a therapy context means making decisions about whether a client needs therapy, which methods would be best, and how to assess whether the treatment is effectively meeting the client’s needs (Marsh et al., Citation2018). Hence, it might be important for the therapists to be more conscious of all the emotional skills and how to observe them in clinical decision-making.

The “implication component of emotional skills” (Salokivi et al., Citation2021) was not a part of the focus group questions and the content analysis because of the component’s broadness. However, interestingly, the participants underlined the fluency of daily functioning as the best indicator of the progress of emotional skills. This may reflect the fact that the implicational component of emotional skills is also an integral part of the components of emotional skills. The music therapy research also presents that music therapy is a useful approach to support the same skills that are mentioned under the implication component, for example, self-management (Gadberry & Harrison, Citation2016; Keen, Citation2004; Strehlow, Citation2009; van der Walt & Baron, Citation2006; Whitehead Pleaux et al., Citation2007) and social skills’ progress among children and adolescents (Chen et al., Citation2019; Gooding, Citation2011; Pater et al., Citation2021; Pavlicevic et al., Citation2014).

Useful perspectives for working on emotional skills in early adolescents with mental health conditions

Participants in this study also identified certain characteristics of working with early adolescents. Early adolescents often avoid dealing with emotions. Early adolescents’ and children’s willingness to avoid emotion-eliciting situations has also been reported in the case of anxiety disorders (Mathews et al., Citation2014; Suveg & Zeman, Citation2004). Early adolescents with mental health conditions need a lot of emotional support and a strong sense of security in the therapeutic relationship, to be ready to deal with personal emotional issues and move forward in the therapeutic process.

The findings suggest that modelling and mirroring are effective methods in therapy practice when working with early adolescents. The idea of modelling is based on Bandura’s Social Learning Theory which emphasizes learning by observing, modelling, and imitating the behaviour, attitudes, and emotional reactions of others (Bandura & Goslin, Citation1969). In the context of therapy, modelling offers the client new patterns of behaviour and coping strategies (Rosenthal et al., Citation1978). By mirroring, the therapist communicates attentiveness, but also prepares the ground for a more personal expression by the client. By mirroring, the therapist also helps the client to become more aware of what has just been expressed (Ferrara, Citation1994).

Our analysis highlighted playfulness and humour as the therapist’s working attitude when working among early adolescents. This attitude has been suggested for working with young people in general (McFerran, Citation2010; McFerran, Citation2020) Playfulness and humour promote connection and build a relationship between client and therapist (Amir, Citation2005; Haire & Macdonald, Citation2019).

The study also highlights the importance of a family-centred working approach. The same approach has also been recommended in the music therapy literature earlier (Jacobsen & Thompson, Citation2016; Oldfield & Flower, Citation2008). Working together with parents and guardians allows for the application of new emotional skills for daily life.

In addition, when working with the target group and emotional skills-related issues, the results of this study emphasize the importance of reflecting transference feelings and clinical supervision. Transference feelings can be divided into transference and countertransference feelings. The first is a dynamic of the client’s conscious and unconscious feelings relating to the therapist, and the second is the therapist’s conscious and unconscious feelings relating to the client (Bruscia, Citation1998). Related clinical supervision and its importance as a means of examining transference of the therapist is important (Bruscia, Citation1998). The importance of professional supervision is also noted in Jackson (Citation2008), Kennelly et al. (Citation2012), and Kennelly et al. (Citation2016).

The results of the study also provide music therapists with perspectives on how to assess when emotional skills are sufficient. In general, smooth daily functioning was the most important indicator of adequate emotional skills. In addition, a shared understanding of the client’s situation between therapist, client, caregivers, and teacher is essential. In the psychotherapy literature, criteria for the end of therapy include the recovery of appropriate emotional functioning, age-appropriate functioning, a sense of emotional integration, improvement in social relationships, and the ability to think emotionally about self and others (Lanyado et al., Citation2010). Participants in this study also described these changes. Such general improvements are also mentioned in a meta-analysis by Gold et al. (Citation2004), where music therapy is reported to reduce behavioural problems and improve overall development in children with psychopathological problems.

Future research

In the future, this research could be extended by larger samples of music therapists, within internationally and culturally diverse contexts. Further research is also needed to explore the relationship between music therapy and sufficiently good daily functioning. Identified skill progress and therapy methods may vary between different diagnostic groups, and further research is needed to provide more accurate and targeted information. The conceptual model of the components of emotional skills in early adolescents was created based on studies of the general population of early adolescents, so variation may exist among clients with special needs, and these variations need to be explored.

Critical reflections on the research

To increase the trustworthiness of the study, we used Lincoln and Guba’s qualitative research criteria including reflections around credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1986). Credibility creates confidence that the results are truthful and credible for the participants. The credibility of this study was enhanced by participants’ opportunity for discussion and critique during the interviews, independent review of the coding and results by another researcher, regular peer discussions with the research team, and regular discussions of the study at dissertation seminars. In addition, the focus group interviews followed recommended focus group interview procedures and the interviewer had prior knowledge of the research methodology. Dependability means a logical and reasoned continuum of data collection, data analysis and theory generation, the quality of which can be assessed and monitored by other researchers. In this study, dependability has been reinforced by describing the research methods and steps as precisely as possible, and by using direct quotes from the interviews in the research report. Confirmability gives confidence that other researchers will confirm the results. The confirmability of this study is enhanced by regular reviews of research choices, both at dissertation seminars and with the research team. In addition, during the focus group interviews, the interviewer regularly checked with the participants that she had correctly understood the content produced by the interviewees. Transferability refers to the extent to which results can be generalized or transferred to other contexts or settings. The transferability of this study is enhanced by appropriate sampling and at least partial (full data saturation will probably never be possible) data saturation in focus groups. The discussion moved on to the next question only when the previous question did not bring up any new perspectives. Moreover, all four interview groups raised fairly similar points of view, and no completely new aspects emerged to any significant extent as the group changed.

To increase the trustworthiness and quality of the study, methodological reporting follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., Citation2007) and the EPICURE guidelines for qualitative research (Stige et al., Citation2009). The COREQ checklist and the EPICURE evaluation report are presented in the supplemental materials of this study (Suppl. 3 and 4).

Despite the effort to produce high quality and dependable research data, research always contains the potential for varying degrees of bias. A broad target population (mental health conditions) may introduce biases by excluding features relevant to a particular diagnostic group. Bias can also be caused by the cultural context. This study, conducted in a northern welfare state among white Finnish music therapists, reflects their perception of the subject and the results may not be applicable to other cultures.

Conclusions

This study provides an overview of progress in emotional skill development and music therapy methods when working with early adolescents with mental health problems. The study presents a conceptual model of the components of emotional skills as one possible framework for music therapy work, which can help music therapy researchers to structure their research on emotional skills. The model will also help music therapists to structure their thinking and reflections on working with emotional skills with early adolescents. The study also provides many useful considerations for practical music therapy work when working with early adolescents with mental health problems to develop emotional skills.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (543.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.1 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2023.2169336

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maija Salokivi

Maija Salokivi MA, is a music therapist and a doctorand of University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She has been working several years with children and adolescents with psychiatric and neurological problems. The aim of her PhD dissertation is to develop an assessment instrument for emotional skills of early adolescents in the context of music therapy. Her research interests include assessment, assessment development, emotional skills, children and adolescents.

Sanna Salantera

Sanna Salanterä PhD, RN, Professor of Clinical Nursing Science, Vice Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at University of Turku and Nurse Director at Turku University Hospital. She is specialized in clinical nursing science, nursing and patient decision-making, smart technology in nursing, pain nursing, health service research, children’s nursing and empowering patient education. She leads the research programs “Health producing basic care with smart technology” and “Health producing health promotion with smart technology”. Both projects consist of several sub projects.

Suvi Saarikallio

Suvi Saarikallio PhD, currently a professor of Music Education and Docent of Psychology at Music, Art and Culture studies at University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She is a member of music psychology research team and widely conducts research and teaching in music psychology, music education, and music therapy. She is currently the President of Finnish Society for Music Education (FiSME) and the Secretary General of European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music (ESCOM).

Esa Ala-Ruona

Esa Ala-Ruona PhD, Associate Professor, music therapist and psychotherapist working as a senior researcher at the Music Therapy Clinic for Research and Training, at University of Jyväskylä, Finland. His research interests are music therapy assessment and evaluation, and in studying musical interaction and clinical processes in improvisational psychodynamic music therapy, and furthermore the progress and outcomes of rehabilitation of stroke patients in active music therapy. Currently he is the president of the European Music Therapy Confederation. He regularly gives lectures and workshops on music therapy both nationally and internationally.

References

- Amir, D. (2005). Musical humour in improvisational music therapy. Australian Journal of Music Therapy, 16, 3–24. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.409894769542038

- Atlas.ti (8.4.5). 2019. ATLAS.ti scientific software development GmbH (Version 8.4.5) [Mac educational license]. https://atlasti.com/

- Bandura, A. (1969). Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 213–262). Rand McNally.

- Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: Pathways and reflections. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617699280

- Barbour, R. (2007). Doing focus groups. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208956

- Brinkmann, S. (2013). Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University Press.

- Bruscia, K. E. (1998). An introduction to music psychotherapy. In K. E. Bruscia (Ed.), The dynamics of music psychotherapy (pp. 18–29). Barcelona Publishers.

- Carr, A. (2015). The handbook of child and adolescent clinical psychology. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315744230

- Chen, C. J., Chen, Y. C., Ho, C. S., & Lee, Y. C. (2019). Effects of preferred music therapy on peer attachment, depression, and salivary cortisol among early adolescents in Taiwan. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(9), 1911–1921. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13975

- Corsini, R. (2016). The Dictionary of Psychology. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315781501

- Davey, C. G., Yücel, M., & Allen, N. B. (2008). The emergence of depression in adolescence: Development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016

- DeepL GmbH. (2017). DeepL Translator. https://www.deepl.com/translator

- Denham, S. A., Bassett, H., Mincic, M., Kalb, S., Way, E., Wyatt, T., & Segal, Y. (2012). Social-emotional learning profiles of preschoolers’ early school success: A person-centered approach. Learning and Individual Differences, 22(2), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.05.001

- Denham, S. A., Blair, K. A., Demulder, E., Levitas, J., Sawyer, K., Auerbach-Major, S., & Queenan, P. (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development, 74(1), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00533

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Ferrara, K. W. (1994). Therapeutic ways with words. Oxford University Press.

- Finnish Society for Music Therapy. (2021, April 8). Musiikkiterapiaa eri asiakasryhmille. https://www.musiikkiterapia.net/index.php/mita-musiikkiterapia/musiikkiterapia-eri-asiakasryhmille

- Friedlander, L. H. (1994). Group music psychotherapy in an inpatient psychiatric setting for children: A developmental approach. Music Therapy Perspectives, 12(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/12.2.92

- Gadberry, A. L., & Harrison, A. (2016). Music therapy promotes self-determination in young people with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 4(2), 95–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2016.1130580

- Geipel, J., Koenig, J., Hillecke, T. K., Resch, F., & Kaess, M. (2018). Music-based interventions to reduce internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.035

- Gold, C., Saarikallio, S., Crooke, A. H. D., & Skewes McFerran, K. (2017). Group music therapy as a preventive intervention for young people at risk: Cluster-randomized trial. Journal of Music Therapy, 54(2), 133–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thx002

- Gold, C., Voracek, M., & Wigram, T. (2004). Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(6), 1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00298.x

- Gonçalves, S. F., Chaplin, T. M., Turpyn, C. C., Niehaus, C. E., Curby, T. W., Sinha, R., & Ansell, E. B. (2019). Difficulties in emotion regulation predict expressive symptom trajectory from early to middle adolescence. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 50(4), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00867-8

- Gooding, L. F. (2011). The effect of a music therapy social skills training program on improving social competence in children and adolescents with social skills deficits. Journal of Music Therapy, 48(4), 440–462. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/48.4.440

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & McKenna, K. (2017). How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods, 29(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16639015

- Haire, N., & Macdonald, R. (2019). Humour in music therapy: A narrative literature review. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 4(28), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2019.1577288

- Hakomäki, H. (2020). Storycomposing: An interactive and creative way to express one’s own musical inventions. In Creativity and the Child (pp. 147–156). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9781848880061_015

- Hendricks, C. B., Robinson, B., Bradley, L. J., & Davis, K. (1999). Using music techniques to treat adolescent depression. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 38(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-490x.1999.tb00160.x

- Humphrey, N., Curran, A., Morris, E., Farrell, P., & Woods, K. (2007). Emotional intelligence and education: A critical review. Educational Psychology, 27(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410601066735

- Jackson, N. A. (2008). Professional music therapy supervision: A survey. Journal of Music Therapy, 45(2), 192–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/45.2.192

- Jacobsen, S. L., & Thompson, G. (Eds.). (2016). Music therapy with families: Therapeutic approaches and theoretical perspectives. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Kaikkonen, M. (2016). Music for all: Everyone has the potential to learn music. In D. V. Blair & K. A. McCord (Eds.), Exceptional music pedagogy for children with exceptionalities: International perspectives. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190234560.001.0001

- Keen, A. W. (2004). Using music as a therapy tool to motivate troubled adolescents. Social Work in Health Care, 39(3–4), 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v39n03_09

- Kennelly, J., Baker, F., Morgan, K., & Daveson, B. (2012). Supervision for music therapists: An Australian cross-sectional survey regarding views and practices. Australian Journal of Music Therapy, 23, 41–57. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/supervision-music-therapists-australian-cross/docview/1112922992/se-2?accountid=14774

- Kennelly, J. D., Daveson, B. A., & Baker, F. A. (2016). Effects of professional music therapy supervision on clinical outcomes and therapist competency: A systematic review involving narrative synthesis. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 25(2), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2015.1010563

- Kitzinger, J. (2005). Focus group research: Using group dynamics to explore perceptions, experiences and understandings. In I. Holloway (Ed.), Qualitative research in health care (pp. 56–70). Open University Press.

- Lanyado, M., & Horne, A. (2010). The therapeutic setting and process. In M. Lanyando & A. Horne (Eds.), The handbook of child and adolescent psychotherapy: Psychoanalytic approaches (pp. 157–174). Routledge. https:R̥0.43249780203877616

- Layman, D. L., Hussey, D. L., & Laing, S. J. (2002). Music therapy assessment for severely emotionally disturbed children: A pilot study. Journal of Music Therapy, 39(3), 164–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/39.3.164

- Liamputtong, P. (2011). Focus Group Methodology: Principles and Practice. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957657

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986(30), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1427

- Malti, T., & Cheah, C. S. L. (2021). Toward complementarity: Specificity and commonality in social-emotional development: Introduction to the special section. Child Development, 92(6), e1085–1094. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13690

- Marsh, J. K., De Los Reyes, A., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2018). Leveraging the multiple lenses of psychological science to inform clinical decision making: Introduction to the special section. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(2), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617736853

- Mathews, B. L., Kerns, K. A., & Ciesla, J. A. (2014). Specificity of emotion regulation difficulties related to anxiety in early adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 37(7), 1089–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.08.002

- Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2002). Emotional intelligence: Science and myth. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2704.001.0001

- McFerran, K. (2010). Adolescents, music and music therapy: Methods and techniques for clinicians, educators and students. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- McFerran, K. (2020). Adolescents and music therapy: Contextualized recommendations for research and practice. Music Therapy Perspectives, 38(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miz014

- Montello, L., & Coons, E. E. (1998). Effects of active versus passive group music therapy on preadolescents with emotional, learning, and behavioral disorders. Journal of Music Therapy, 35(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/35.1.49

- Oldfield, A., & Flower, C. (Eds.). 2008. Music therapy with children and their families. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Parker, J. G., Rubin, K. H., Erath, S. A., Wojslawowicz, J. C., & Buskirk, A. A. (2006). Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method (pp. 419–493). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Pater, M., Spreen, M., & van Yperen, T. (2021). The developmental progress in social behavior of children with autism spectrum disorder getting music therapy. A multiple case study. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105767

- Patterson, S., Duhig, M., Darbyshire, C., Counsel, R., Higgins, N. S., & Williams, I. (2015). Implementing music therapy on an adolescent inpatient unit: A mixed-methods evaluation of acceptability, experience of participation and perceived impact. Australasian Psychiatry, 23(5), 556–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856215592320

- Pavlicevic, M., O’Neil, N., Powell, H., Jones, O., & Sampathianaki, E. (2014). Making music, making friends: Long-term music therapy with young adults with severe learning disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 18(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629513511354

- Rosenthal, T. L., & Bandura, A. (1978). Psychological modeling: Theory and practice. In S. L. Garfield & A. E. Begin Chichester (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change: An empirical analysis (pp. 621–658). John Wiley.

- Saarni, C. (1999). The Development of Emotional Competence. Guildford Press.

- Salmela-Aro, K. (2011). Stages of Adolescence. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Adolescence (pp. 360–368). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373951-3.00043-0

- Salokivi, M., Salanterä, S., & Ala-Ruona, E. (2021). Scoping review and concept analysis of early adolescents’ emotional skills: Towards development of a music therapy assessment tool. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 31(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2021.1903977

- Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Blakemore, S. -J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A. C., & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5

- Shuman, J., Kennedy, H., Dewitt, P., Edelblute, A., & Wamboldt, M. Z. (2016). Group music therapy impacts mood states of adolescents in a psychiatric hospital setting. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 49, 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.014

- Smithson, J. (2008). Focus Groups. In P. Alasuutari, L. Bickman, & J. Brannen (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods (pp. 357–430). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446212165

- Social Insurance Institution of Finland. (2020). Social Insurance Institution’s rehabilitation statistics. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/315063?locale-attribute=en

- Solbakken, O. A., Hansen, R. S., Havik, O. E., & Monsen, J. T. (2011). Assessment of affect integration: Validation of the affect consciousness construct. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.558874

- Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005

- Stige, B., Malterud, K., & Midtgarden, T. (2009). Toward an agenda for evaluation of qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 19(10), 1504–1516. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309348501

- Strehlow, G. (2009). The use of music therapy in treating sexually abused children? Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 18(2), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098130903062397

- Suveg, C., & Zeman, J. (2004). Emotion regulation in children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33(4), 750–759. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_10

- Taarvig, E., Solbakken, O. A., Grova, B., & Monsen, J. T. (2015). Affect consciousness in children with internalizing problems: Assessment of affect integration. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20(4), 591–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104514538434

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Uhlig, S., Jansen, E., & Scherder, E. (2018). “Being a bully isn’t very cool … ”: Rap & sing music therapy for enhanced emotional self-regulation in an adolescent school setting – a randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Music, 46(4), 568–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735617719154

- van der Walt, M., & Baron, A. (2006). The role of music therapy in the treatment of a girl with pervasive refusal syndrome: Exploring approaches to empowerment. Australian Journal of Music Therapy, 17, 35–53. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/role-music-therapy-treatment-girl-with-pervasive/docview/208663882/se-2?accountid=14774

- Wasserman, N. M. (1972). Music therapy for the emotionally disturbed in a private hospital. Journal of Music Therapy, 9(2), 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/9.2.99

- Webropol. (2020, July 31). Webropol Internet Questionnaire. https://new.webropolsurveys.com/

- Whitehead Pleaux, A., Zebrowski, N., M Baryza, M. J., & Sheridan, R. (2007). Exploring the effects of music therapy on pediatric pain: Phase 1. Journal of Music Therapy, 44(3), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/44.3.217

- Wigelsworth, M., Humphrey, N., Kalambouka, A., & Lendrum, A. (2010). A review of key issues in the measurement of children’s social and emotional skills. Educational Psychology in Practice, 26(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667361003768526

- World Health Organization. (2021, August 9). Adolescent mental health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

- Zimmermann, P., & Iwanski, A. (2014). Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(2), 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413515405

- Zins, J. E., & Elias, M. J. (2006). Social and emotional learning. In G. G. Bear & K. M. Minke (Eds.), Children’s needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention (pp. 1–13). National Association of School Psychologists.