ABSTRACT

Introduction

Music therapy has growing evidence for its effectiveness in mental health. People with mental health conditions often face significant barriers in obtaining personal valued social roles and feeling a sense of belonging to their community. Overcoming these barriers is an important step in the recovery process. This pilot study investigated whether long-term group music therapy might have an impact on participants’ social skill development, group cohesion and expression of emotional states.

Method

The study was an exploratory, retrospective, quantitative, longitudinal single-case study (N = 8). Five video recorded sessions were selected and micro-analyzed by independent raters, who rated the Group Environmental Scale (n = 8) and Individual Behavior Observation Categorization scale (n = 4). Statistical analysis was carried out to identify trends over time. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04435405).

Results

A longitudinal improvement was found in the group domains of Relationship (1.6-fold), Personal growth (1.9-fold) and System maintenance (1.5-fold) along the 9-month follow-up period. On the individual level, an improvement was found over time in social skills and group cohesion (4.85-fold), affect (3.15-fold), and musical activities performances (19.9-fold).

Discussion

The study demonstrated longitudinal improvement trends in social skills, group cohesion and expression of emotional states (affect) in the group as a whole and in each of the four individual assessments. Future studies which will include a larger sample and longer follow-up periods are needed.

Introduction

People with mental health conditions (MHC)Footnote1 often face significant barriers in obtaining personally valued social roles and feeling a sense of belonging to their community. MHC often lead to stigma and discrimination, difficulty to establish interpersonal connections and increased social isolation with reduced social networks (Grocke et al., Citation2009). Sociability and satisfying social networks are important factors for people living with MHC as they are associated with enhanced hope and well-being (Solli, Citation2015; Tew et al., Citation2012). There are growing efforts to develop and implement programs which focus on well-being and community integration to reclaim the “right to a safe, dignified, and personal and gratifying life in the community despite his or her psychiatric condition” (Davidson et al., Citation2008, p. 11).

Music therapy has been practiced for many decades with growing evidence for its effectiveness with different populations, including people with MHC. The definition of music therapy that guided this project is as follows: “Music therapy is a reflexive process wherein the therapist helps the client to optimize health, using various facets of music experiences and the relationships formed through them as the impetus for change” (Bruscia, Citation2014, p. 26). Musicking can have a pivotal influence on socialization and in building inter-personal skills. It has the potential to be effective as a community-based therapeutic approach in bringing people together in a shared experience and provides an important step toward integration back to the community (Ansdell, Citation2002; Stige & Aaro, Citation2012). These qualities may bring people with MHC closer to their communities and reinforce their own sense of better life and health.

Although music therapy is defined as a psychosocial treatment in line with other Recovery-Oriented Services (ROS), it is unique and is considered one of the creative arts therapies which goes “beyond words” allowing the therapist to do something positive with people rather than to people (Pedersen, Citation2014). As such, music therapy is a health-focused interactive process that can address social isolation and enhance the formation of relationships. The positive effects of music therapy on social isolation, as enhancing socialization and social inclusion, has been described among people with schizophrenia in both inpatient and community settings (Grocke et al., Citation2009; Solli, Citation2015; Tang et al., Citation1994). Several studies have investigated the effect of weekly music therapy group sessions among people living with MHC in the community (Carr et al., Citation2017; Erkkilä et al., Citation2011; Gold et al., Citation2009; Grocke et al., Citation2009; Windle et al., Citation2020). These studies reported that some service users primarily experienced music therapy in positive terms related to their mental health and well-being, such as having a good time, feeling connected and better able to express their feelings (McCaffrey et al., Citation2018). Moreover, music therapy is considered an engaged social and cultural practice, and as a natural agent of health promotion (Ansdell, Citation2002; Tseng et al., Citation2016). Music therapy could be seen as sharing core principles with the recovery approach such as empowerment, well-being, social capital, resource-orientation, and a community-orientation that avoid labeling people by their disorder or disability (Ansdell, Citation2014; Leonhardt et al., Citation2017; Solli, Citation2015; Solli & Rolvsjord, Citation2015).

Research in music therapy for people with MHC has commonly focused on a clinical perspective of recovery such as symptom reduction and functional improvement (Gold et al., Citation2013). It should be noted however, that there is a paradigm shift from treating illness to supporting personal recovery by utilizing music therapy’s unique capabilities to promote positive change in various life domains (Solli & Rolvsjord, Citation2015).

A recent meta-analysis (Jia et al., Citation2020) evaluated the impact of adjunct music therapy for people living with schizophrenia (18 studies, 1212 participants) and found significant improvement in total symptoms, negative symptoms, depressive symptoms and quality of life. Similarly, findings from a systemic review and meta-analysis (Zhao et al., Citation2016) suggest that music therapy has a positive effect on reducing depressive symptoms among adults with depression. It is important to note, however, that almost all these studies examined in-patient, short-term music therapy interventions (Geretsegger et al., Citation2017). A meta-analysis conducted by Silverman (Citation2003) indicated that music therapy was effective in suppressing psychotic symptoms. A meta-analysis by Tseng et al. (Citation2016) that included 12 studies (total of 804 participants) found that inpatients with schizophrenia who received adjunctive music therapy reported significant improvement and reduction of positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and mood symptoms compared to the control group. Meta-regression analysis found that music therapy significantly alleviates disease severity for people with schizophrenia, especially those with a long-standing condition (Tseng et al., Citation2016). Another meta-synthesis (Solli et al., Citation2013) and a multiple single case study (Solli & Rolvsjord, Citation2015) demonstrated that clients’ experiences regarding group music therapy resemble many of the recognized benefits of recovery-oriented group practices. Further, a study conducted by Kwon et al. (Citation2013) with 55 inpatient adults with schizophrenia who received multiple group music therapy sessions found that music therapy improved cognitive function, and positive behaviors compared to the control group. Similarly, Bibb and McFerran (Citation2018) revealed that singing can facilitate mental health recovery by focusing on the strengths and resources of consumers and their capacity to use music as a health resource in their own recovery. Additional outcome studies have documented positive effects of music therapy on symptoms and functioning for people with psychotic disorders (Gold et al., Citation2009, Citation2013; Mössler et al., Citation2012). However, Solli and Rolvsjord (Citation2015) linked such positive effects to the experience of well-being rather than to a reduction of negative symptoms. Grocke et al. (Citation2014) studied 99 participants with MHC in a randomized cross-over trial of 13 weeks group music therapy and found that group music therapy enhanced quality of life, self-esteem, and spirituality.

Supportive and hope-inspiring relationships are found to be important and effective for recovery and associated with growth, development, and well-being (Jetten et al., Citation2014; Solli, Citation2015). This is highly relevant to music therapy as group cohesion during music therapy sessions plays an important role in shaping participants’ response to each other, building positive and mutual contacts, and offering experience of togetherness and belonging, all of which are important for social recovery (Solli, Citation2015; Wilson et al., Citation2008). Similarly, previous meta-analyses of RCTs comparing music therapy as an additional treatment to standard care alone for people with psychotic disorders showed large effects on negative symptoms, including affect (Gold et al., Citation2005; Tseng et al., Citation2016). Music therapy is likely to support people with MHC to express themselves and their emotions and relate to others through musical means to build satisfying social relationships (Gold et al., Citation2009, Citation2013).

The increasing evidence for the benefits of music therapy on global and mental state, symptom improvement, and as a medium for emotional expression, is a driving force for developing music therapy services for people with MHC in the community. Music therapy has already been included in national treatment guidelines for people with psychosis in the UK and in Norway (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Citation2010; The Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2013). Despite the growing recognition of music therapy’s contribution and importance, there is a need to further study the effect of music therapy on well-being, and particularly on social skill development and emotional expression. Our pilot study aims to better understand the impact of longitudinal, weekly group music therapy for people living with MHC in community settings over a period of nine months. The study will explore behavioral domains such as individual’s social skill development and emotional expression. Specifically, we asked the following questions:

Will long-term music therapy group sessions in the community have a positive effect on social skills and group cohesion?

Will long-term music therapy group sessions in the community have a positive effect on expression of emotional states (affect)?

These behaviors were chosen since they can serve as indicators for satisfying social recovery and well-being (Solli, Citation2015), can build up gradually through group meetings, and can be observed and quantified.

Method

Research design

This article is based on the dissertation of the corresponding author (Schneidman, Citation2020).

This pilot study was an exploratory, retrospective, quantitative, longitudinal single-case study. It was designed to observe changes in different behavioral, emotional, social and musical domains as well as the development of group cohesion during nine months of weekly group music therapy.

For this purpose, all music therapy sessions were video recorded and five of the sessions were quantitively micro-analyzed to rate 2 scales: one scale tested individual participants’ performance (social skills and group cohesion, active participation in musical activities, emotional expression states); and the second scale tested group performance as a whole (relationship, personal growth and system maintenance). Both scales score several behavioral domains, focusing on social skills, affect and group cohesion, and will be described further in the following section. The study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04435405).

Participants and setting

The music therapy group included eight adults aged between 20 and 65 years. There were four women and four men, and all were long-term service-users with MHC living in Israel. The number of years of being an inpatient varied widely amongst the participants, ranging from 0 to 4 years. None of the participants required a hospital admission during the research data collection period.

Only those group members who attended all the music therapy sessions were included in the assessment of group outcomes (see GES measure below. Further, only those participants whose behavior was fully captured in all video-recordings were included in the individual behavior analysis (see IBOC measure below). Four out of the eight individuals fulfilled this criterion, and their behaviors were analyzed.

To be eligible for participation in this study, participants had to meet Israeli criteria for “psychiatric disability” severe enough to compromise at least 40% of one’s functioning (roughly comparable to the U.S. designation of Severe Mental Illness). While we did not conduct diagnostic interviews for each participant, their diagnoses were made by their psychiatrist according to DSM-5 criteria and all of our study participants had either psychotic or mood disorder (schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorders), as well as difficulties with expressing emotions and establishing social connections. None of the participants had previous music education, but all had a strong interest in music.

The group members participated in a weekly music therapy group in a mental health community center in central Israel between March 2019 and December 2019. The center provides rehabilitation services to people living with chronic (and severe) mental health conditions in the community. The objective of this music therapy group was defined as a music therapy community program based on individual and group work to promote well-being by empowering self-esteem and personal growth and to develop relationships and social networks expansion through musical activities. The music therapy sessions were co-facilitated by a qualified and experienced music therapist and a psychiatrist who is also a musician with experience in conducting groups. Both the music therapist and the psychiatrist received ongoing supervision from a senior music therapist. The music therapy group facilitators designed the objectives and means of this group based on a model previously implemented for youth at risk (Krüger, Citation2018). This model is based on the ideas and values of Community Music Therapy (Stige & Aaro, Citation2012) and Resource-Oriented Music Therapy (Rolvsjord, Citation2010) focusing participants’ strengths and resources rather than on their psychopathology.

The group sessions took place one hour per week for nine months. The content of the sessions varied in musical activities and was developed across four phases. During the first three months (phase one) “musical presentations” (Amir, Citation2012, pp. 176–193), improvisation, familiar prerecorded songs and singing took place. The musical presentation was a way for group members to present themselves to the group through sharing recorded music that was meaningful for them. Sharing music gradually created a safe place for each group member as they became familiar with each other and developed interpersonal skills as well as musical skills. Verbal interactions took place as the participants reflected on their thoughts and emotions of their musical experiences and being in the group. During the second phase, the group members continued to improvise, listen and sing to familiar songs, however they also began working in small groups or individually with the music therapist. These sessions included mainly personal song writing. The personal songs were brought back to the larger group for feedback, singing and performing for each other. The third phase included performing for guests within the centre, who joined the group sessions as members, being recipients and participants at the same time. These performances allowed the group members to experience the excitement as well as tension often experienced when performing live. The fourth, and last phase was dedicated to the rehearsals for an upcoming Holiday concert. The anticipation toward the concert was one of the strategies to increase participants’ sense of empowerment. In addition to that, weekly discussions with group members explored whether the expectations of the group were met, and changes were collaboratively applied accordingly.

The musical interventions were based on songs that were selected by the participants from their own collections, as well as from a list of popular songs that were suggested by the facilitator. The participants were offered to write their own songs during individual sessions and to perform them together with the group. The group members had free choice to select their musical piece and the other group members could join the performance by playing musical instruments or singing. The musical instruments available included a variety of percussion instruments such as drums, tambourine, xylophone, bells, electric guitar, wooden flutes, and a synthesizer. The participants were encouraged by the facilitator to play different instruments during every performance.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol and informed consent form were approved by the ethics committee for the evaluation of research with human subjects of the Faculty of Social Welfare & Health Sciences, Haifa University, Israel. The participants gave signed consent following oral and written explanations of the study. Participants’ confidentiality was maintained at all times. Data, including the video films, were stored and handled securely, and were destroyed upon study completion.

Analysis

Longitudinal video micro-analysis was carried out to answer the research questions, which focus on whether the music therapy group in the community has an influence on social skills development, group cohesion and emotional states (affect) improvement. According to Wosch and Wigram (Citation2007), video microanalysis is a comprehensive and a powerful tool when investigating aspects related to interaction and communication. Assessment of video recordings has successfully been used to explore the long-term effects of psychotherapeutic interventions in people with MHC (Isbell et al., Citation1992).

Five music therapy sessions, out of 30 filmed during the course of group music therapy, were selected for the study by the group psychiatrist who co-facilitated the sessions. These five time points (with equal time periods in between) were selected to follow the development of the group during the nine months of the music therapy program: baseline (at the beginning of the course), after two, four and five months (a six-month video was not included due to technical quality issue) and at the end of the course (9 months). The time points of each video were masked.

Measures

Video recording micro-analysis was based on two scales (see assessment scales, Supplementary Online Material).

Individual Behavior Observation Categorization (IBOC)

The first scale focused on individual participant assessment – Individual Behavior Observation Categorization (IBOC – based on Brotons & Pickett-Cooper, Citation1996; Solé et al., Citation2014). The IBOC is based on categorization of observations performed by counting the frequency of the tested behavior categories with a minimal frequency of “0”, while the higher score indicates a better performance. The Categorization of Observation of Individual Behavior (Brotons & Pickett-Cooper, Citation1996) uses an appraisal method that measures behavior against levels of performance and also measures the frequency with which the behaviors occur. It was successfully used to analyze videos of music therapy sessions in dementia patients, and music participation behaviors were well adopted (Solé et al., Citation2014). When adopting the IBOC assessment tool into their music therapy study, Solé et al. reported it to be highly reliable with an interrater variability rate of 91%.

Five behavioral categories which are simple to quantify in a video film are followed (Solé et al., Citation2014): Verbalization, Physical contact, Visual contact (gaze), Active participation in musical activities, and Emotions/facial affect and body expressions.

The rater quantifies the number of specific events that the tested individuals exhibit, for example, how many times in the session the individual had visual contacts with other participants. While each session lasts 1 hour, the assessment was carried out between minute 23–46 (overall 23 minutes of each session). This time frame was suggested by the music therapist as it represents the time frame where the musical activity is the most pronounced during the meeting.

The IBOC is highly relevant to this study as it focuses on the domains of social skills and group cohesion, participation in music activity, and affect (emotional expression states). When looking at the different behavioral categories in more depth, the scale includes three dimensions, which are closely related to social-emotional areas addressed in music therapy: well-being, social relations, and personal development. These domains are quantified as follows (Solé et al., Citation2014):

Social skills and group cohesion = Verbalization, Physical contact, Visual contact (gaze) and Active participation in music activities.

Active participation in music activity = to assess the degree of engagement in singing, playing instruments, music listening, music and movement & improvisation.

Affect = Emotional expression states.

The results of each of the three dimensions will be presented for the research participants in each of the selected time points.

Group Environmental Scale (GES)

The second scale focused on group assessment – Group Environmental Scale (GES) (Alexander & Skinner, Citation2002; Isbell et al., Citation1992; Wilson et al., Citation2008). The GES consists of 10 subscales with 9 questions in each with overall 90 true/false questions on an answer form. The minimal score is “0” and the maximal score is “90”, with a higher score indicating a better performance.

The Group Environmental Scale (GES) offers a quantitative method for assessing intervention support groups (Moos, Citation1986). The GES has psychometrically established reliability, factor structure, content, and construct validity. It is brief, taking short time to complete 90 true/false items on an answer form. The GES was originally designed to be rated by group members. To make it suitable for external rating, we slightly altered the wording of the questions without changing their meanings. For example, the original statement “Group members feel close to each other” was modified to “Group members show that they care for one another”. The GES has been previously used to analyze different group interventions and group environments including in mental health patients (Alexander & Skinner, Citation2002; Isbell et al., Citation1992; Lavoie, 1981; Wilson et al., Citation2008). The GES evaluates 10 “group environment” subscales: Cohesion, Leader (therapist) support, Expressiveness, Independence, Task orientation, Self-discover, Anger and aggression, Order and organization, Leader (therapist) control, and Innovation. Isbell et al. (Citation1992) who used GES to explore long-term group psychotherapy in people with MHC demonstrated that 9 of the 10 subscales had an inter-rater agreement of more than 62%. The task orientation subscale, however, inter-rater agreement was only 38%. The authors concluded that all of the subscales except task orientation were deemed sufficiently reliable to be retained for analysis.

The GES is highly relevant to the study as it focuses on group cohesion domains, which are grouped into 3 dimensions which best represent the group environment (for detailed description please refer to the assessment scales supplement, Moos, Citation1986):

Relationship = Cohesion, Leader support, Expressiveness.

Personal Growth = Independence, Task orientation, Self-discovery, (-) Aggression.

System maintenance and change = Order and organization, Leader control, Innovation.

Ratings of the GES and IBOC

The GES and IBOC ratings were carried out by three health-care providers in a masked fashion (medical doctor specialized in neurology, a person with master degree in community mental health rehabilitation who is the first author and a person with master degree in public health sciences). These masked raters (to the time points of the filmed sessions) completed the GES group analysis for the eight participants, and one masked rater completed the IBOC individual analysis for the four included participants. In order to reduce inter-rater variability and to minimize bias, the raters were trained by one of the study researchers on the use of the GES. The training process included analyzing videos (which were not from those intended for the study evaluation) and comparing and discussion scores. The training continued until 75% raters’ agreement was achieved (the actual overall inter-rater agreement in the study was 78%). For the analysis, each video session was watched once with no interruptions, and immediately after the video ended, the GES scale was filled out by each of the three raters.

Results

This community-based music therapy group program was conducted according to the structured program detailed in the participants and setting section of the method, and the objective of the program was met.

Individual Behavior Observation Categorization Scale (IBOC) analysis

Four participants whose behavior was fully captured in three video-recordings (baseline, 5-, and 9-months; 2- and 4-months analyses were not performed as individual behaviors of the four participants were not fully visible) were included in the individual behavior analysis. All four participants live with either schizophrenia or schizoaffective conditions with different levels of social functioning challenges.

The following presents the results of the social skills and group cohesion development:

Table 1. Social skills and group cohesion development.

presents the results of Individual Dynamics in Active participation in music activities.

Table 2. Individual dynamics in active participation in music activities.

presents the results of Emotional expression states (Affect).

Table 3. Emotional expression states (affect).

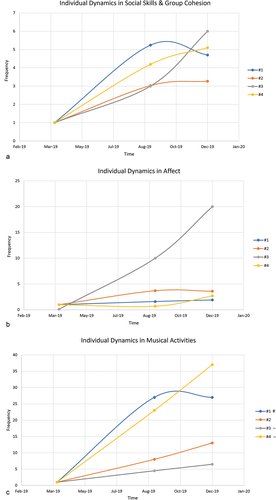

The results indicate that there was an increase over time in all three dimensions for all four participants: Social skills and group cohesion demonstrates a median of 4.85-fold improvement over nine months, affect increased by a median of 3.15-fold, and musical activities performances increased by a median of 19.9-folds (see Supplementary Data_IBOC for the raw data). Participant #3, who started the music therapy sessions with pronounced flatted affect and the lowest functioning level, demonstrated the most pronounced improvement over time in the social skills and affect dimensions. summarizes the individual dynamics in social skills and group cohesion (A), affect (B), and active participation in musical activities (C) normalized to the baseline scores.

Figure 1. Individual behavior dynamics of four participants in three dimensions: (a) Social skills and group cohesion, (b) Affect, and (c) Active participation in musical activities over 9 months of MT. The score is the relative score at each time point to the baseline score (one external rater).

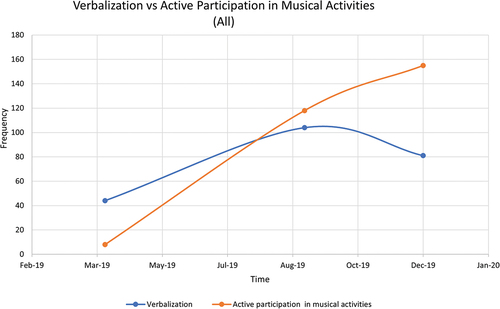

Additionally, both verbalization and participation in musical activities increased over the first six months of the music therapy, yet, only the musical performances continued to increase until the end of the music therapy sessions () and the proportion of musical activities during the meetings became more prominent from meeting to meeting.

Group Environmental Scale (GES) analysis

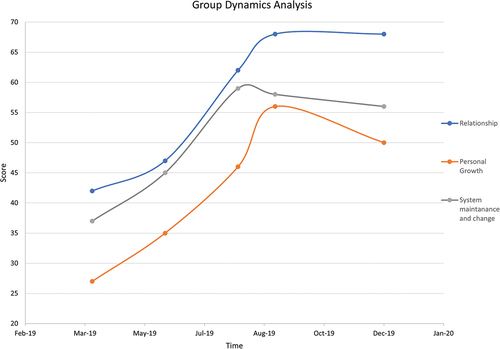

presents the sum of the three raters’ adjudication for each domain in each time point for the whole group (n=8). The results revealed that there was a longitudinal increase in all three domains evaluated: Relationship 1.6-fold, Personal growth 1.9-fold and System maintenance and change 1.5-fold along the follow-up period (see Supplementary Data_GES for the raw data). The maximal improvement appeared from baseline to five months, reaching a plateau thereafter ().

Figure 3. Group dynamics of 3 dimensions (relationship, personal growth, system maintenance) over 9 months of MT. The score is the cumulative score of the 3 external raters.

Table 4. Sum of the three raters’ adjudication for each domain in each time point for the whole group (n = 8).

Discussion

This pilot study investigated if there is a signal of effect of a long-term music therapy group in the community on individuals with MHC in social skill development and emotional expression states. Results revealed improvements in both group and individual performances during nine-months-long music therapy. More specifically we found evidence of benefit (i.e. an increase in the scales scores) in the parameters that reflect social skills and group cohesion development in both the group (relationship and personal growth) and the individual (verbalization, physical contact, visual contact and active participation in music activities) behavioral dynamics over 9 months. An improvement in emotional expression states (affect) was also evident.

The improvement in group cohesion is consistent with Solli (Citation2015) and Wilson et al. (Citation2008) who claimed that group cohesion during music therapy sessions has a role in shaping the participants’ response to each other, building positive and mutual contacts, and offering experience of togetherness and belonging. These supportive and hope-inducing relationships are found to be important in the recovery process of people with MHC and are associated with growth, development, and well-being (Jetten et al., Citation2014; Solli, Citation2015). These findings highlight music therapy’s uniqueness in promoting positive identity, developing relationships, and expanding social networks and social cohesion (Solli & Rolvsjord, Citation2015; Wang & Agius, Citation2018). This research is in agreement with recent findings which showed that adults with MHC who engaged in bi-weekly music therapy sessions over a six-week period, which included interventions that encouraged learning about and using socially appropriate behaviors, demonstrated an increase in prosocial behaviors such as initiating conversation, participating in reciprocal exchanges, and expressing emotions (Baumgarten & Wheeler, Citation2016).

The current findings also suggest that music therapy may improve participant’s emotional expression states (affect). Past research has similarly shown that music therapy was effective for the treatment of affect flattening and bluntness and general lack of interest (Geretsegger et al., Citation2017; Gold et al., Citation2005; Tseng et al., Citation2016). Additionally, music has been associated with enhanced mood, well-being, morale and reduction of the risk of depression in people with MHC and other chronic disorders and positively affects emotions (Daykin et al., Citation2018; Silverman, Citation2019; Quach & Lee, Citation2017). A recent study by Windle et al. (Citation2020) is consistent with these findings that music therapy stimulates new feelings, and songwriting can encourage emotional expression in people dealing with depression. Our study used a quantitative approach, measuring the frequencies of observed behaviors, which can serve as surrogates for affect: happiness, sadness, relaxation, anger, and agitation. We observed that shortly after the initiation of the group sessions, the video camera became a transparent object in the room and the participants seemed to ignore its presence. Including objective data adds value to the validity of the findings as the video microanalysis approach bypasses the subjective response, which is more common in qualitative research.

The effect of music therapy in addressing affective flattening or blunting, low motivation, and poor social relationships (Gold et al., Citation2009) is interesting because it may help explain the “mechanisms of change” within music therapy. First, music could be considered a medium for emotional expression that may help to improve and broaden an individual’s expressive range, which may result in diminishing affect flattening. Second, making music together could be considered a social endeavor, inherently supporting connections and building social relationships. Solli and Rolvsjord (Citation2015), for example, found in a qualitative study in inpatient participants with MHC that most participants related their engagement in music therapy to a renewed motivation for being in contact with others with a sense of self and identity. Finally, music therapy could be considered helpful in assisting people to express emotions and experiences, and to communicate them to others through musical expression of emotions within playing instruments, improvising and singing (Solli et al., Citation2013). All three mechanisms of change suggested here were evident in this project: the participants with flattened affect demonstrated positive changes in emotional expression states; musical activities increased over time enabling meaningful communication between the group members; and playing and singing together became the most prominent part of the sessions.

Of note, the improvements in the group cohesiveness and affect were accompanied with an observed decline in the group members’ aggressiveness. These observations are similar to previous research findings (Tseng et al., Citation2016) reporting that music therapy reduces aggressive behavior in people with MHC. Jesna et al. (Citation2016) reviewed music therapy and concluded that the positive effect of music therapy on aggression reduction is apparent if at least 40 sessions are delivered. The reduction in aggressive behaviors in our group was evident in a much smaller dose, following the first 20 sessions. We propose that the possibility for promoting social bonding and interpersonal communication in music therapy might be the basis for the alleviation of aggressive expressions. However, an additional explanation may be related to the fact that in this group all members, including the two facilitators, were perceived equal to each other and no hierarchic structure was applied. Everyone could freely suggest means to improve the group goals within the shared journey.

The improvement in group dynamics reached a plateau in this study after six months (about 20 meetings). This improvement is similar to what was reported in a previous Cochrane Review (Geretsegger et al., Citation2017) that classified the studies with respect to total duration of therapy as short-term music therapy (up to 12 weeks), medium term (13 to 26 weeks), and long term (more than 26 weeks). The review suggested that at least 20 music therapy sessions are needed in order to reach clinically significant effects, which follows the dose-effect relationships found in Gold et al. (Citation2009) and in Chung and Woods-Giscombe (Citation2016) in people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders.

Although both verbalization and participation in musical activities increased over the first six months of the music therapy, only the musical activities continued to improve until the end of the nine month music therapy course. This musical improvement involved an increase in active participation in all musical activities, which included a wide variety of musical engagement including free improvisations, singing from songbooks and participants’ original songs, and playing instruments. In all four participants analyzed with the IBOC, the proportion of participation in musical activities during the meetings became more prominent from meeting to meeting. Each of the four participants took part in musical activities that created opportunities for group cohesion (playing together) as well as for individual expression (singing solo original songs). Pavlicevic and Ansdell (Citation2004) argued that music making may be self-reinforcing since the creation of sound influences and changes the immediate environment. When people influence the environment through the creation of sound, they perceive themselves as facilitating the change in the environment and eliciting the responses from others, leading to them experiencing a sense of self-efficacy. The belief in one’s efficacy is usually associated with positive emotions (Pellitteri, Citation2009). These results are in line with previous studies where music therapy participation supported service users to feel more vital, uplifted, joyful, hopeful, and motivated, and enabled them to become more active participants in their everyday lives (Solli & Rolvsjord, Citation2015) and in creating social bonding (Pearce et al., Citation2015).

Participants of this study were heterogeneous in terms of difficulties in establishing social connections and management of daily activities (based on the psychiatrist’s individual participant data report). Nevertheless, the positive individual dynamics in social skill development and affect improvement over time was apparent in all four participants analyzed with the IBOC, with participant #3, who started the music therapy group with the most flatted affect and the lowest social functioning level and motivation, demonstrating the most pronounced social skill and affect improvement. Several reports have suggested that music therapy may have unique motivating, relationship-building, and emotionally expressive qualities that may help even those who do not benefit from verbal therapies (Solli, Citation2008) or show little or no motivation (Gold et al., Citation2009, Citation2013). Furthermore, music therapy has been shown to help build social cohesion through developing emotional collaboration, thereby producing more cooperative relationships (Bang, Citation2016). Improvements in social aspects are important because impairments in the ability to build and sustain satisfying relationships with others are often the core challenges for people living with MHC (Gold et al., Citation2013).

This study also highlights the influence of the group facilitator in achieving the group goals. Although the results show a persistent level of support (i.e. encouraging members to be active during the sessions and careful listening to their needs being heard and understood) the facilitator involvement gradually decreased toward the end of music therapy. For example, over the course of 5 months, leader control increased 1.32 fold in the first month, and then decreased over the next 4 months by 0.87 fold. This finding is in agreement with Isbell et al. (Citation1992), who reported a decrease in therapist control over time in a group therapy of people with schizophrenia. A possible explanation to this change could be that music therapy involves a meeting of both professionals and service users as experts, equal partners and co-facilitators in the process. In community music therapy approaches where the music therapist aims that the process will generate well-being in individuals and in their communities (Ansdell, Citation2014), the therapist is considered as a “guest” who guides and follows the members in any way they choose to use music (Ansdell, Citation2002). When the group becomes more organized and cohesive, the active guidance of the “guest” facilitator becomes less crucial.

This study has limitations. First, this is a pilot study that was planned with a small sample size and therefore inferential statistical analyses were not suitable. In addition, it was a single arm study, and therefore the results obtained may be caused from the fact that the participants were meeting each other on regular basis, enjoying each other’s company, and have something to do - a purpose, hope, etc. Second, the analysis was conducted on eight participants who completed the program. This approach to analysis could lead to a bias due to the relation between program completions to the outcome. Third, the participants had more than group music therapy, they had individual and small group sessions, they presented their songs at a weekly gathering where there were guests and where they had positive feedback. The impact of the individual and small group sessions is very likely to have contributed to the results, so it is not solely a group intervention. Fourth, in the GES scale, a few original statements were slightly changed following the raters training session, to make the statements clearer to the raters. However, we believe the meaning of the statements remained the same after the wording change, and therefore that this did not affect the content validity of the assessment. Fifth, although the raters were masked to the session’s time points, a possible bias might still have occurred. For example, in one session, the raters could guess the meeting date as the participants discussed the upcoming Jewish new-year holiday. Sixth, as only one video camera was used to film the sessions, the eight group members were not fully captured in all sessions and therefore the IBOC analysis could only be performed on four participants, which might skew the results. The use of additional cameras to capture other angles would solve this issue in future studies.

Therefore, the results of our relatively small cohort pilot study may serve as the basis to inform the design of a larger-scale trial in the future to see if the results can be replicated. Additionally, future research should test whether the observed social skill improvements within the music therapy sessions are also reflected more broadly in the participants’ daily lives. Furthermore, it is important to test if the results are repeatable in long-term music therapy groups in the community which implement similar protocols, and if the proposed three mechanisms of change apply to those groups.

Conclusions

In this pilot quantitative exploratory study, we found improvements in both group and individual behaviors among eight people with MHC who completed a nine-month music therapy group. These findings indicate that long-term group music therapy may be effective in improving social skills and emotional expression states to achieve satisfying social recovery and well-being in people living with severe MHC in the community.

The research findings might be a first step toward the application of long-term group music therapy program for people with MHC in the community in Israel as well as in other countries, as is now being recommended in national treatment guidelines in the UK and Norway (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Citation2011; The Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2013).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the external raters: Yoram Solberg MD, PhD and Assi Valdhorn MpH, for their help with rating the scales, and all the participants who kindly agreed to participate in this study. This study was completed in partial fulfillment for a master’s degree of the corresponding author (Schneidman, Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2023.2204898

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alona Schneidman

Alona Schneidman, MA in Community Mental Health, is a PhD student in the Department of Community Mental Health, Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, University of Haifa Israel and graduating certificate studies in psychotherapy in University of Haifa, Israel. Her PhD thesis study investigates Pathways to Care, Treatment Dosage of Care, Early Disengagement, and Post- Early Intervention Program Services Among Individuals with First Episode Psychosis.

Cochavit Elefant

Cochavit Elefant, PhD is Professor in Music Therapy and Head of graduate training course in music therapy at the School for Creative Arts Therapies, University of Haifa, Israel. She is a researcher at the Emily Sagol Research Center. Previously, she worked as Associate Professor in Music Therapy at the Grieg Academy –University of Bergen. She received her PhD from Aalborg University. Her research areas include music therapy and children with Rett syndrome, Autism, mental health, neo-natal and Community Music therapy.

Ronel Keren

Ronel Keren, MD is Psychiatrist working in a Day Care Unit in the Beer Yaakov Mental Health facility and also in Enosh, the Israeli Mental Health Association. Co-founder of the music therapy groups in community centers for people with severe mental conditions.

Stav Ben-Shachar

Stav Ben-Shachar MA, Music Therapist and Co-founder of the music therapy groups in community centers for people with severe mental conditions. Graduated the School for Creative Arts, University of Haifa, Israel. Works with varied populations such as mental health, Autism and Refugee children.

David Roe

David Roe, Ph.D. is a licensed clinical psychologist, Professor and chair of the Department of Community Mental Health, director of The Centre for Mental Health Research, Practice and Policy at the University of Haifa, Israel and affiliated Professor at Aalborg University, Denmark. After receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree (Magna Cum Laude) in psychology from Brown University he went on to Columbia University where he received his Masters of Philosophy, Masters of Science and Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology before completing a post-doc at Rutgers University. His research focuses on the psychosocial processes of recovery from serious mental illness, stigma, Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and the evaluation of interventions and services. Dr. Roe has published extensively and serves as associate editor for the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, Journal of Mental Health, BMC psychiatry and Israel Journal of Psychiatry and is on the editorial board of Psychiatry Research, Journal of Clinical Psychology, Psychiatry Research Communications, Stigma and Health, Journal of Clinical Psychology, Psychosis, American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation and Social Welfare (Hebrew).

Notes

1 This term is taken from the United Nations General Assembly report on Mental health and Human rights (Citation2017). In this study we are focusing on people who live with severe MHC. We used the term “mental health condition” which is more appropriate and consistent with the resource-oriented recovery approach instead of the traditional psychiatric term “severe mental disorder” which belongs to the clinical recovery approach.

References

- Alexander, D., & Skinner, B. (2002). A pilot study using the group environment scale to evaluate first-year resident support groups. Family Medicine, 34(10), 732–737. PMID: 12448642.

- Amir, D. (2012). “My music is me”: Musical presentation as a way of forming and sharing identity in music therapy group. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 21(2), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2011.571279

- Ansdell, G. (2002). Community music therapy & the winds of change. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.15845/voices.v2i2.83

- Ansdell, G. (2014). Revisiting ‘community music therapy and the winds of change’ (2002): An original article and a retrospective evaluation. International Journal of Community Music, 7(1), 11–45. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.7.1.11_1

- Bang, A. H. (2016). The restorative and transformative power of the arts in conflict resolution. Journal of Transformative Education, 14(4), 355–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344616655886

- Baumgarten, H. R., & Wheeler, B. L. (2016). The effects of music therapy on the prosocial behaviors of adults with disabilities. Music and Medicine, 8(3), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.47513/mmd.v8i3.475

- Bibb, J., & McFerran, K. S. (2018). Musical recovery: The role of group singing in regaining healthy relationships with music to promote mental health recovery. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 27(3), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2018.1432676

- Brotons, M., & Pickett-Cooper, P. K. (1996). The effects of music therapy intervention on agitation behaviors of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Journal of Music Therapy, 33(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/33.1.2

- Bruscia, K. E. (2014). Defining music therapy (3rd ed.). Barcelona Publishers.

- Carr, C. E., O’Kelly, J., Sandford, S., & Priebe, S. (2017). Feasibility and acceptability of group music therapy vs wait-list control for treatment of patients with long-term depression (the SYNCHRONY trial): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 18(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1893-8

- Chung, J., & Woods-Giscombe, C. (2016). Influence of dosage and type of music therapy in symptom management and rehabilitation for individuals with schizophrenia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(9), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1181125

- Davidson, L., Rowe, M., Tondora, J., O’Connell, M. J., & Lawless, M. S. (2008). A practical guide to recovery-oriented practice: Tools for transforming mental health care. Oxford University Press.

- Daykin, N., Mansfield L., Meads C., Julier G., Tomlinson A., Payne A., Grigsby Duffy L., Lane J., D’Innocenzo G., Burnett A., & Kay T. (2018). What works for wellbeing? A systematic review of wellbeing outcomes for music and singing in adults. Perspectives in Public Health, 138(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913917740391

- Erkkilä, J., Punkanen, M., Fachner, J., Ala-Ruona, E., Pöntiö, I., Tervaniemi, M., & Gold, C. (2011). Individual music therapy for depression: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(2), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085431

- Geretsegger, M., Mössler, K. A., Bieleninik, Ł., Chen, X. J., Heldal, T. O., & Gold, C. (2017). Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(5). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub4.www.cochranelibrary.com

- Gold, C., Heldal, T. O., Dahle, T., & Wigram, T. (2005). Music therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub2

- Gold, C., Mössler, K., Grocke, D., Heldal, T. O., Tjemsland, L., Aarre, T., Aarø, L. E., Rittmannsberger, H., Stige, B., Assmus, J., & Rolvsjord, R. (2013). Individual music therapy for mental health care clients with low therapy motivation: Multicentre randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(5), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348452

- Gold, C., Solli, H., Krüger, V., & Atle, S. (2009). Dose–response relationship in music therapy for people with serious mental disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(3), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.001

- Grocke, D., Bloch, S., & Castle, D. (2009). The effect of group music therapy on quality of life for participants living with a severe and enduring mental illness. Journal of Music Therapy, 46(2), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/46.2.90

- Grocke, D., Bloch, S., Castle, D., Thompson, G., Newton, R., Stewart, S., & Gold, C. (2014). Group music therapy for severe mental illness: A randomized embedded-experimental mixed methods study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 130(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12224

- Isbell, S. E., Thorne, A., & Lawler, M. H. (1992). An exploratory study of videotapes of long-term group psychotherapy of outpatients with major and chronic mental illness. Group, 16(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01459710

- Jesna, C. A., Lalitha, K., Gandhi, S., Nattala, P., & Vijaysagar, J. (2016). Effectiveness of music therapy on aggression as an adjunct therapy. Indian Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 12(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-1505.260550

- Jetten, J., Haslam, C., Haslam, S. A., Dingle, G., & Jones, J. M. (2014). How groups affect our health and well-being: The path from theory to policy. Social Issues and Policy Review, 8(1), 103–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12003

- Jia, R., Liang, D., Yu, J., Lu, G., Wang, Z., Wu, Z., & Chen, C. (2020). The effectiveness of adjunct music therapy for patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113464

- Krüger, V. (2018). Community music therapy as participatory practice in a child welfare setting – a Norwegian case study. Community Development Journal, 53(3), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsy021

- Kwon, M., Gang, M., & Oh, K. (2013). Effect of the group music therapy on brain wave, behavior, and cognitive function among patients with chronic schizophrenia. Asian Nursing Research, 7(4), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2013.09.005

- Leonhardt, B. L., Huling, K., Hamm, J. A., Roe, D., Hasson-Ohayon, I., McLeod, H. J., & Lysaker, P. H. (2017). Recovery and serious mental illness: A review of current clinical and research paradigms and future directions. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 17(11), 1117–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2017.1378099

- McCaffrey, T., Carr, C., Solli, H. P., & Hense, C. (2018, January). Music therapy and recovery in mental health: Seeking a way forward. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.15845/voices.v18i1.918

- Moos, R. H. (1986). Group environment scale manual. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Mössler, K., Chen, X. J., Heldal, T. O., & Gold, C. (2012). Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia- like disorders. Cohrane Databaseof Systematic Reviews, 12, 1–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub3

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2011). Common mental health disorders: Identification and pathways to care. British Psychological Society.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (Great Britain), National Institute for Health, Clinical Excellence (Great Britain), British Psychological Society, & Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2011). Common mental health disorders: Identification and pathways to care. O’Grady, L. (2012).

- The Norwegian Directorate of Health. (2013). Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for utredning, behandling og oppfølging av personer med psykoselidelser [National guidelines for assessment, treatment, and follow-up of persons with psychotic illnesses]. Author. http://helsedirektoratet.no/

- Pavlicevic, M., & Ansdell, G. (2004). Community music therapy. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Pearce, E., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. I. (2015). The ice-breaker effect: Singing mediates fast social bonding. Royal Society Open Science, 2(10), 150221. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150221

- Pedersen, I. N. (2014). Music therapy in psychiatry today – do we need specialization based on the reduction of diagnosis-specific symptoms or on the overall development of patients’ resources? Or do we need both? Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 23(2), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2013.790917

- Pellitteri, J. (2009). Emotional processes in music therapy. Barcelona Publishers.

- Quach, J., & Lee, J. A. (2017). Do music therapies reduce depressive symptoms and improve QOL in older adults with chronic disease? Nursing 2019, 47(6), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000513604.41152.0c

- Rolvsjord, R. (2010). Resource-oriented music therapy in mental health care. Barcelona Publishers.

- Schneidman, A. (2020). Group music therapy for people living with mental health conditions in the community: A quantitative micro-analysis processes [Doctoral dissertation, University of Haifa (Israel)]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2020. 28764883.

- Silverman, M. J. (2003). The influence of music on the symptoms of psychosis: A meta-analysis. Journal of Music Therapy, 40(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/40.1.27

- Silverman, M. J. (2019). Quantitative comparison of group-based music therapy experiences in an acute care adult mental health setting: A four-group cluster-randomized study. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 28(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2018.1542614

- Solé, C., Mercadal-Brotons, M., Galati, A., & De Castro, M. (2014). Effects of group music therapy on quality of life, affect, and participation in people with varying levels of dementia. Journal of Music Therapy, 51(1), 103–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thu003

- Solli, H. P. (2008). ”Shut up and play!”—Improvisational use of popular music for a man with schizophrenia. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 17(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098130809478197

- Solli, H. P. (2015). Battling illness with wellness: A qualitative case study of a young rapper’s experiences with music therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 24(3), 204–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2014.907334

- Solli, H. P., & Rolvsjord, R. (2015). “The opposite of treatment”: A qualitative study of how patients diagnosed with psychosis experience music therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 24(1), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2014.890639

- Solli, H. P., Rolvsjord, R., & Borg, M. (2013). Toward understanding music therapy as a recovery-oriented practice within mental health care: A meta-synthesis of service users’ experiences. Journal of Music Therapy, 50(4), 244–273. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/50.4.244

- Stige, B., & Aaro, L. E. (2012). Invitation to community music therapy. Australian Journal of Music Therapy, 23, 76–78. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203803547

- Tang, W., Yao, X., & Zheng, Z. (1994). Rehabilitative effect of music therapy for residual schizophrenia: A one-month randomised controlled trial in Shanghai. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165(S24), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1192/S0007125000292969

- Tew, J., Ramon, S., Slade, M., Bird, V., Melton, J., & Boutillier, C. L. (2012). Social factors and recovery from mental health difficulties: A review of the evidence. British Journal of Social Work, 42, 443–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr076

- Tseng, P. T., Chen, Y. W., Lin, P. Y., Tu, K. Y., Wang, H. Y., Cheng, Y. S., & Wu, C. K. (2016). Significant treatment effect of adjunct music therapy to standard treatment on the positive, negative, and mood symptoms of schizophrenic patients: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0706-4

- United Nations. (2017). Mental health and human rights. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/861008

- Wang, S., & Agius, M. (2018). The use of music therapy in the treatment of mental illness and the enhancement of societal wellbeing. Psychiatria Danubina, 30(Suppl 7), 595–600. .

- Wilson, P. A., Hansen, N. B., Tarakeshwar, N., Neufeld, S., Kochman, A., & Sikkema, K. J. (2008). Scale development of a measure to assess community-based and clinical intervention group environments. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(3), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20193

- Windle, E., Hickling, L. M., Jayacodi, S., & Carr, C. (2020). The experiences of patients in the synchrony group music therapy trial for long-term depression. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 67, 101580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2019.101580

- Wosch, T., & Wigram, T. (2007). Microanalysis in music therapy: A comparison of different models and methods and their application in clinical practice, research and teaching music therapy. In Microanalysis in music therapy: Methods, techniques and applications for clinicians, researchers, educators and students (pp. 298–318). Jessica Kingsley.

- Zhao, Q. F., Tan, L., Wang, H. F., Jiang, T., Tan, M. S., Tan, L., & Yu, J. T. (2016). The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069