Abstract

Classical Aboriginal culture in Australia consists of many different kinds of ceremonies, including travelling ceremonies that are often shared across linguistic and geographical boundaries. Each of these ceremonies is made up of dozens of different verses. Perhaps the most widely known travelling ceremony is one referred to in some areas as ‘Wanji-wanji’. This was known over half the country and dates back at least 170 years, as evidenced in eleven legacy recordings and fieldwork interviewing more than 100 people across the western half of Australia. Like any oral tradition, the names of such ceremonies vary from place to place and from individual to individual. The extent to which a ceremony was known can thus only be seen through analysis of the music itself, rather than through reference to its names. This study analyses the most widely known verse in this ceremony, which we refer to as the Wanji-wanji verse. We identify the similarities and differences of the Wanji-wanji verse across legacy recordings spanning fifty years across three states. The most significant variation can be seen in the northern and southern peripheries of its ‘broadcast’ footprint. Our fieldwork has involved repatriating audio recordings to their communities of origin and sharing knowledge about the extent to which the ceremony was known. By implication, this activity has equipped custodians with the knowledge and confidence to potentially revive this once immensely popular ceremony.

Introduction

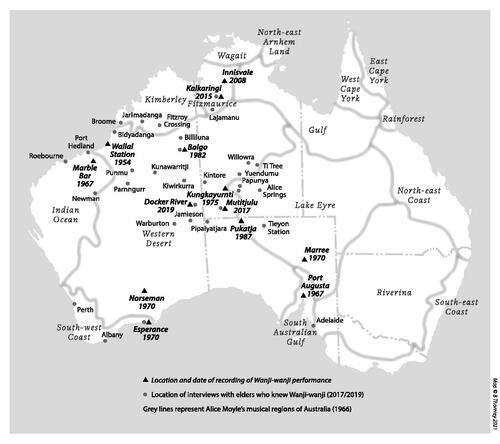

Wanji-wanji is possibly the most widely known Aboriginal ceremony in Australia. It was known from Esperance in the south-west to the Victoria River District in the north, and from Broome to Wilcannia in New South Wales. Ethnographer Daisy Bates witnessed performances of it in the early twentieth century when roads, trains and stock routes were being constructed in the outback, which she regards as having enabled ‘its quick conveyance from tribe to tribe’ (Bates Citation1915, 5). However, by the late 1960s its popularity had declined as choice or circumstance saw the younger generation turn to new forms of music and entertainment. Featuring interrelated elements of dance, visual designs and a repertoire of songs, Wanji-wanji was probably just one of many ‘corroborees’ or public ceremonies that faded from memory as country and western music, movies and travelling shows drew greater attention in the outback.Footnote1

Our research, both in archives and through interviews with people who know the songs of this ceremony, has traced many places where Wanji-wanji was known, who performed it and what it meant to them. Just as the film The Red Violin (Girard Citation1998) tells the story of the many players of this 300-year-old instrument, our research aims to tell the story of the many people who sang or witnessed this once immensely popular ceremony. Wanji-wanji has been passed down orally for at least 170 years. In 1913, on the South Australian coast, Daisy Bates met ‘Old Tharnduriri, who was over 70 years old, [and who] remembered parts of the dance which he had seen at Ayers Rock in his boyhood’ (Bates Citation1938, 125). This means that Wanji-wanji was known in Central Australia from at least the 1850s.

The geographic extent of Wanji-wanji has been just as fascinating to the people who grew up with it as it is to those of us who have studied this ceremony. The surprise of hearing ‘corroboree’ songs like Wanji-wanji hundreds of kilometres from the place it was previously encountered is described by Treloyn (Citation2014), who explores the movement of songs between the Kimberley and the Daly region. Tracing the movement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture through time and place has also been the subject of a recent volume by Harris (Citation2014). Our research is part of this endeavour, as it explores history ‘through a focus on the creative arts and exchange of culture’ (Harris Citation2014, 11). Although the journey of Wanji-wanji primarily involves interactions between Aboriginal groups, this interaction has been significantly impacted by colonial interactions, as suggested in our opening paragraph.

To understand the history of an orally transmitted song, analysis of its music and text is crucial. As already indicated, one cannot rely solely on the name of a song, as a song may not have a name or it may have different names in different regions and times. The performance contexts and significances of a song can be just as diverse (Tunstill in Breen Citation1989, 7). This is the situation with Wanji-wanji, which is known by different names in different regions. Without hearing the ceremony, its identity is in doubt. In the case of Wanji-wanji, this means knowing some thirty-three songs, as a ceremony is made up of multiple songs, or what are sometimes called verses. Our research highlights the importance of a cross-disciplinary approach, which many researchers have also identified (Bracknell Citation2020; Harris Citation2014; Rademaker Citation2016). While a historian can trace leads to all corners of an archive, a song specialist can readily identify a tell-tale refrain of a song, both on the page or upon audition. Such collaboration is better equipped to identify significant gaps when finding recordings in archives and auditioning interviews, as people switch from a snippet of one song to another, and even across different ceremonial repertories.

Once performed as part of a ‘travelling show’ or ‘travel dance’ until at least 1913 (Bates Citation1914d), the songs of this ceremony found a new home in the pastoral industry and, since 1967, some performances were preserved on audio recordings. While the way people conduct and use the Wanji-wanji ceremony varies, the songs themselves have remained remarkably stable. This was evident during recent fieldwork, where we played legacy recordings of one of the most well-known Wanji-wanji songs to many Aboriginal people, who immediately identified it upon first hearing. Some, however, remarked on the different way it was sung. An understanding of the musical features of this song enables us to trace where it has been performed and understand what contemporary singers mean when they listen to various recordings that they can identify as the same song, yet still say it has been ‘sung differently’.

This article aims to identify which features unify the Wanji-wanji style, as well as the regional differences that contemporary singers hear. To help identify these features, we use musical transcription, as distinct from a score, to provide ‘a blueprint drawn after the building is built’ (Winkler Citation1997, 193). We reiterate Marett’s (Citation2005, 6) point that transcription is not meant to represent the sound world it encodes, but rather a road map to help our ears navigate through the sound world. Musical transcription has sometimes been seen as a means of colonial appropriation and exhibition (Tomlinson Citation2007). It nonetheless remains a useful tool in helping to understand what features singers are referencing when they say a song has been sung differently across multiple recordings. We will provide a brief history of the Wanji-wanji ceremony and identify legacy recordings that have formed the basis of our analyses in this article. We will then identify the musical features of Wanji-wanji song and discuss the potential for its revival in the contexts of Aboriginal cultural revitalization programs and broadening engagement with public Aboriginal performance traditions.

The Wanji-wanji Ceremony

The earliest written reference to the Wanji-wanji ceremony was in 1913 by the ethnographer Daisy Bates. She witnessed a performance of it over two weeks at Eucla on the Great Australia Bight in South Australia near the Western Australian border. She noted the ceremony had been in the Pilbara region of Western Australia around the headwaters of the Ashburton, Fortescue and Murchison rivers:

The Wanna-wa or Wanji-wanji as it was known in the River sources areas finished its career while I was camped at Eucla 1913–14: though we had a big group collected for initiation ceremonies and the Wanji travelling group performed it at Eucla … (Bates Citation1914d, 3–5)

Further east on the South Australian coast, Bates later encountered Yulpira speakers of Yuria, who also sang a song of the Wanji-wanji ceremony (Bates Citation1914c):

Since I told you, it has travelled the 240 miles between Eucla and Pentunubu, but it wouldn’t have done that distance in such a short time were it not for the white man’s teams travelling to and fro. (Corroborees as Travelling Shows Citation1915)

In addition to its name as ‘Wanna-wa’ in the southwest, Bates (Citation1914b, 77) notes it was called ‘Wan-narra-barri’ in the Champion Bay area. Our own research finds that people on the Pilbara coast today know it by a similar name, ‘Wanajarra’.Footnote2 This literally means ‘belonging to women’, although elder Steven Stuart (Citation2019) points out ‘but men sing it’.Footnote3 David Stock states ‘a woman got more power than a man’ in it (Stock Citation2018),Footnote4 echoing Bates’s words that ‘Wan-narra is the Gascoyne name for the corroboree in which the women take the leading part (somewhat similar to the wanna-wa corroboree of the south and south-east)’ (Bates Citation1914b, 77). Further inland, it is known as ‘Laka’ or ‘Warriwarnkanya’ in northern South Australia,Footnote5 and as ‘Kulkalanya’ today.Footnote6 In legacy recordings from Port Augusta, Maree, Wilcannia and Papunya (see ), the ceremony was documented as ‘Wanji-wanji’. In the contemporary interviews, many people also knew it by this name, although some did not know it by any particular name at all. This article draws on archival recordings of this song and more than ninety contemporary interviews with people about this song by authors Turpin and Bracknell. The locations of these performances and interviews are shown in .Footnote7

Table 1. Legacy Recordings that include the Wanji-wanji Song and number of instances of it (song items). Recordings 1—3 are rememberings while the others are performances

Our analysis focuses on the most widely known song in the ceremony, which we refer to as the ‘Wanji-wanji song’, as it contains the word ‘Wanji-wanji’. This song can be likened to a ‘title track’ in that this ceremony’s name comes from part of its text.Footnote8 In Eucla in 1913, this song was used to open and close the ceremony (Bates Citation1914a, Citation1938, 136). It is also the opening song in two performances (, recordings 5–6). Some people we interviewed also recalled it as either the opening or closing song. Bates uses the term ‘Wanji-wanji’ to refer to both the ceremony and the travelling group who performed it. Some of the people interviewed recalled that non-Aboriginal stockmen and station people also sang this particular song (Turpin and Meakins Citation2019, 164).Footnote9

‘Wanji-wanji’ is not the only song after which this ceremony is named. ‘Kulkalanya’, as it is known in the north of South Australia, is a word in another of its songs. The Wanji-wanji song, however, is the most frequently heard on legacy recordings of this ceremony and features in ten of its eleven extant recordings (see ). In addition, this song is heard in two documentary films, albeit briefly.Footnote10 In the contemporary interviews, it was also the most easily recognized and widely known song.Footnote11 lists the ten legacy recordings that feature this song and the twenty-four individual ‘song items’ they include overall (Barwick Citation1989, 13). In Aboriginal performance traditions, each song is normally repeated a number of times before another song in the ceremony is sung. On the legacy recordings numbered 1–3 in , the only song sung was the Wanji-wanji song. These are all linguistic recordings, where the informant presumably gave an impromptu song. We refer to them as ‘rememberings’. The other recordings listed in were primarily pre-arranged musical performances.

Not all songs in the Wanji-wanji ceremony are sung within a single performance, as evident in the recorded performances, Bates’s notes and the contemporary interviews. Just as a pop concert will typically only include a selection of an artist’s complete repertoire, a performance of Wanji-wanji will only feature a selection of the ceremony’s larger repertoire of songs. It might also be that some performers from different places do not share the exact Wanji-wanji repertoires of songs and that, over time, a song might be forgotten and another one added by different groups. While some songs occur in only a few different recordings, the Wanji-wanji song is by far the most prevalent. This is perhaps due to its role as the opening and closing song. The Wanji-wanji song is shown in the following with the word ‘wanji-wanji’ emphasized:

(1) Warri warnkanya

Warri warnkanya

Kakanala wanji-wanji wanpanarra

The meaning of the word ‘wanji-wanji’ is unknown. It may simply be a name for the ceremony. The word warri, common in many Western Desert languages, is interpreted as a word meaning ‘cold’ by Pintupi speaker the late Michael Tjakamarra Nelson. We note that in neighbouring Warlpiri the word warri means ‘in a circle’ or ‘around’ (Laughren Citationin press). To Warlpiri speaker, the late Harry Jakamarra Nelson, who knew the song, the overall meaning of these lyrics could be interpreted as ‘Wait, we’re going to sing Wanji-wanji’ or ‘Wait, we’re about to start Wanji-wanji’:

Ngadju man Sonny Graham associates the verse with the meaning ‘I don’t know this country, I’m a traveller’. Both impressions point to a function of the song as part of a social event with people coming together. A possible gloss of the words in this song is as follows. Most singers like those mentioned above, however, do not profess to know the intended meaning of these lyrics and can only postulate about what this may be.

Across all of the recordings listed in , there are only two variants of the text, both of which reduce the non-repeating line to the same eight-beat duration as the repeating line by omitting the word ‘Wanji-wanji’.

(2)Warri warnkanya

Kukunarli wanpanarli. (Bill Harney, Innisvale, Northern Territory, 2007)

(3)Warri warnjanay

Kokanjeri wapanarri. (Sam Dabb, Esperance, Western Australia, 1970)

It is perhaps unsurprising that with neither of these variants is the song documented as ‘Wanji-wanji’. It is of interest that both variants are from the northern (Innisvale) and southern (Esperance) extremities of where the Wanji-wanji song has been recorded (see Figure 1). Oral histories suggest that the song came to both these regions in the course of station work and possibly earlier when it circulated via traditional trade networks. Additionally, the Sam Dabb version (recording 2) from 1970 clearly refers to kokanjeri (sheep) and wap (play) in the local Nyungar language of Esperance, Western Australia.Footnote12 Misheard and adapted song lyrics, known as ‘mondegreens’, are common across a range of language contexts (Turpin and Stebbins Citation2010), especially when songs cross linguistic boundaries. The earliest recorded and most often repeated version of the Wanji-wanji song may be the closest to its original source, which may be the inland Western Desert region (Turpin Citation2019). The Dabb versions, however, seem to have been Nyungarized, and adapted and updated thematically to reflect life in the pastoral industry. In 1970, Sam Dabb, while not well known as a singer himself, described having heard his mother, Annie, sing this version (von Brandenstein Citation1969–70). Given the dramatic and prolonged disruption to Nyungar singing traditions in Australia’s populous southwest (Bracknell Citation2020), differences could also possibly be the result of imperfect ‘remembering’.

The Wanji-wanji Song

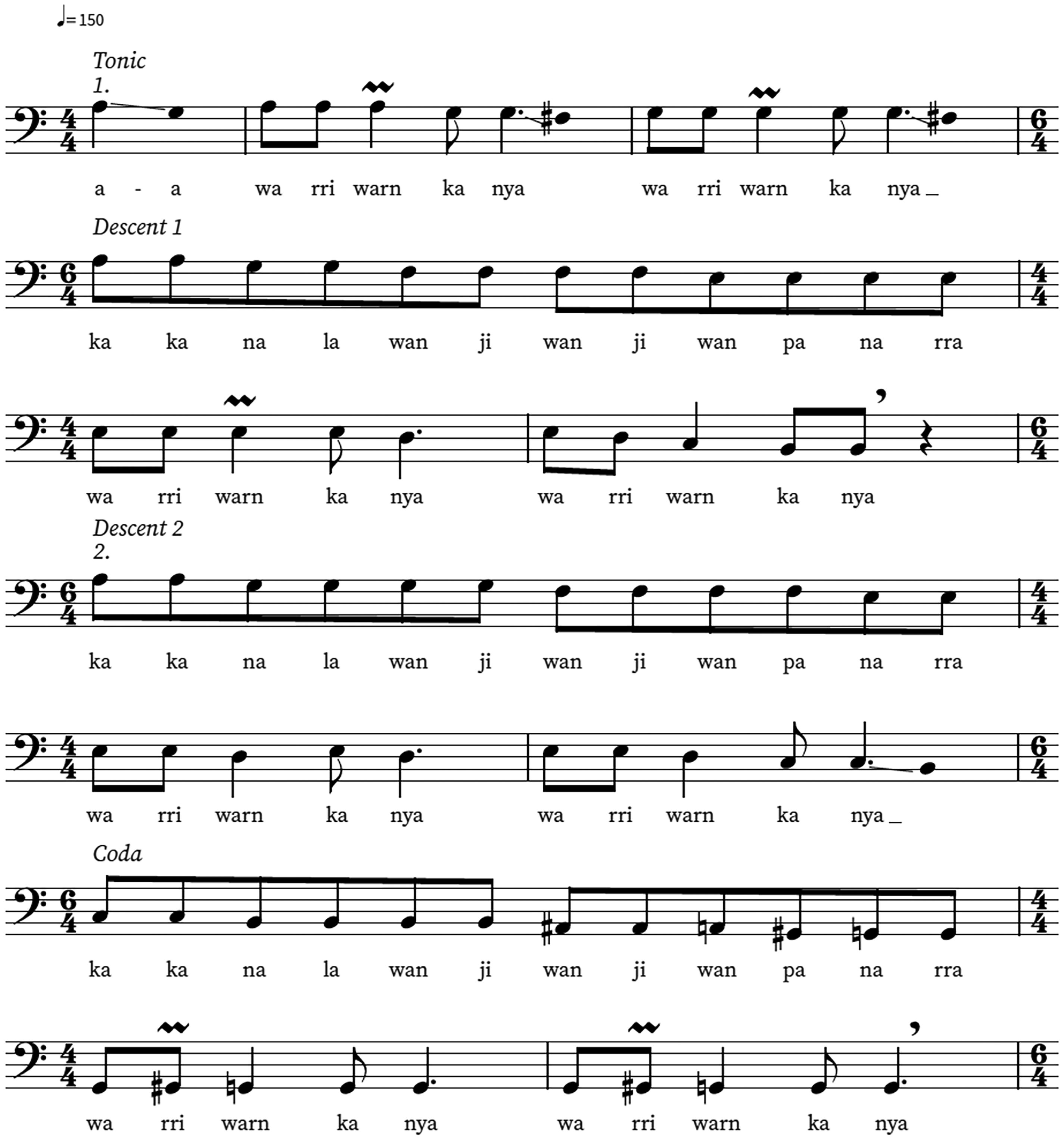

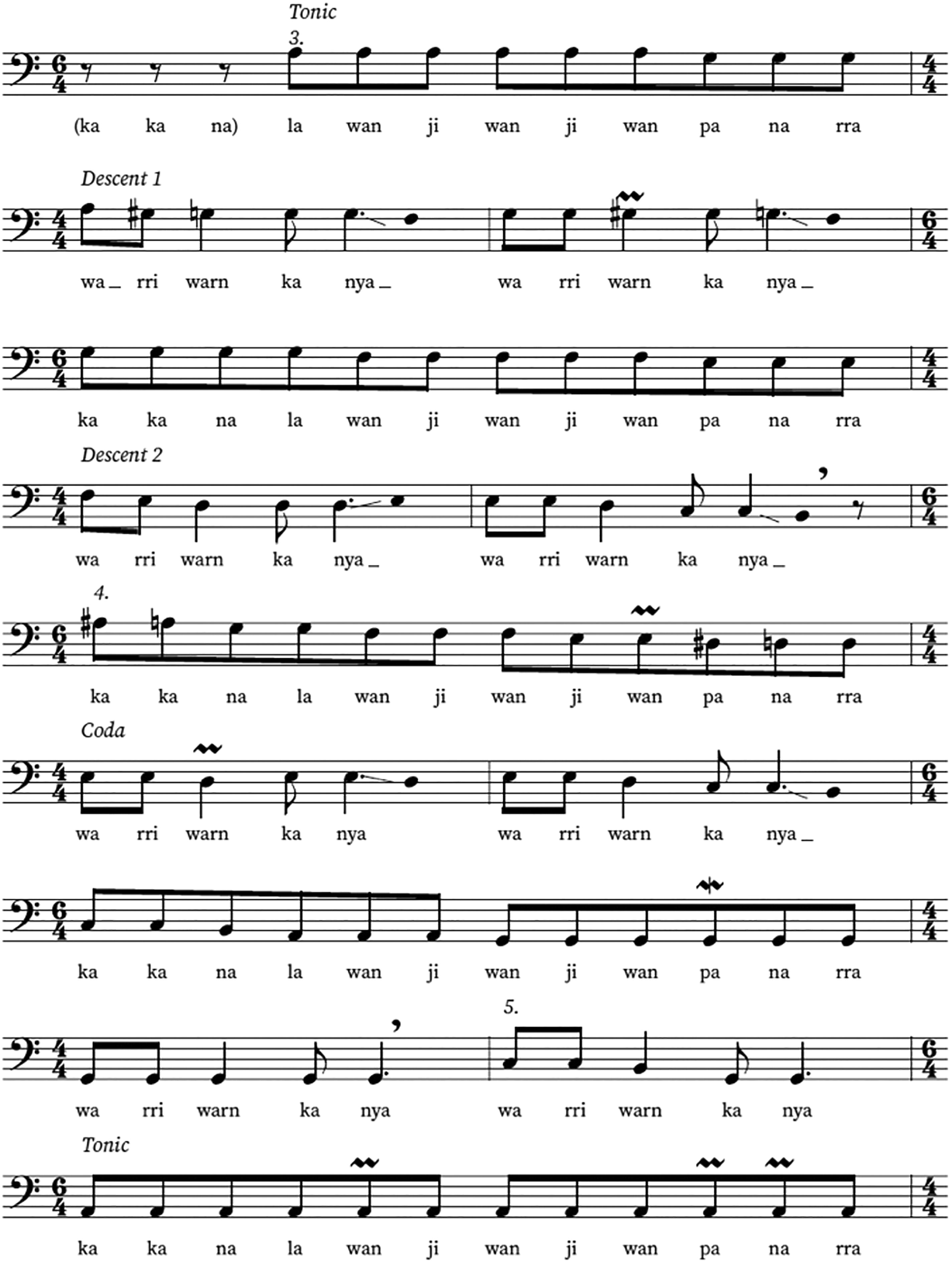

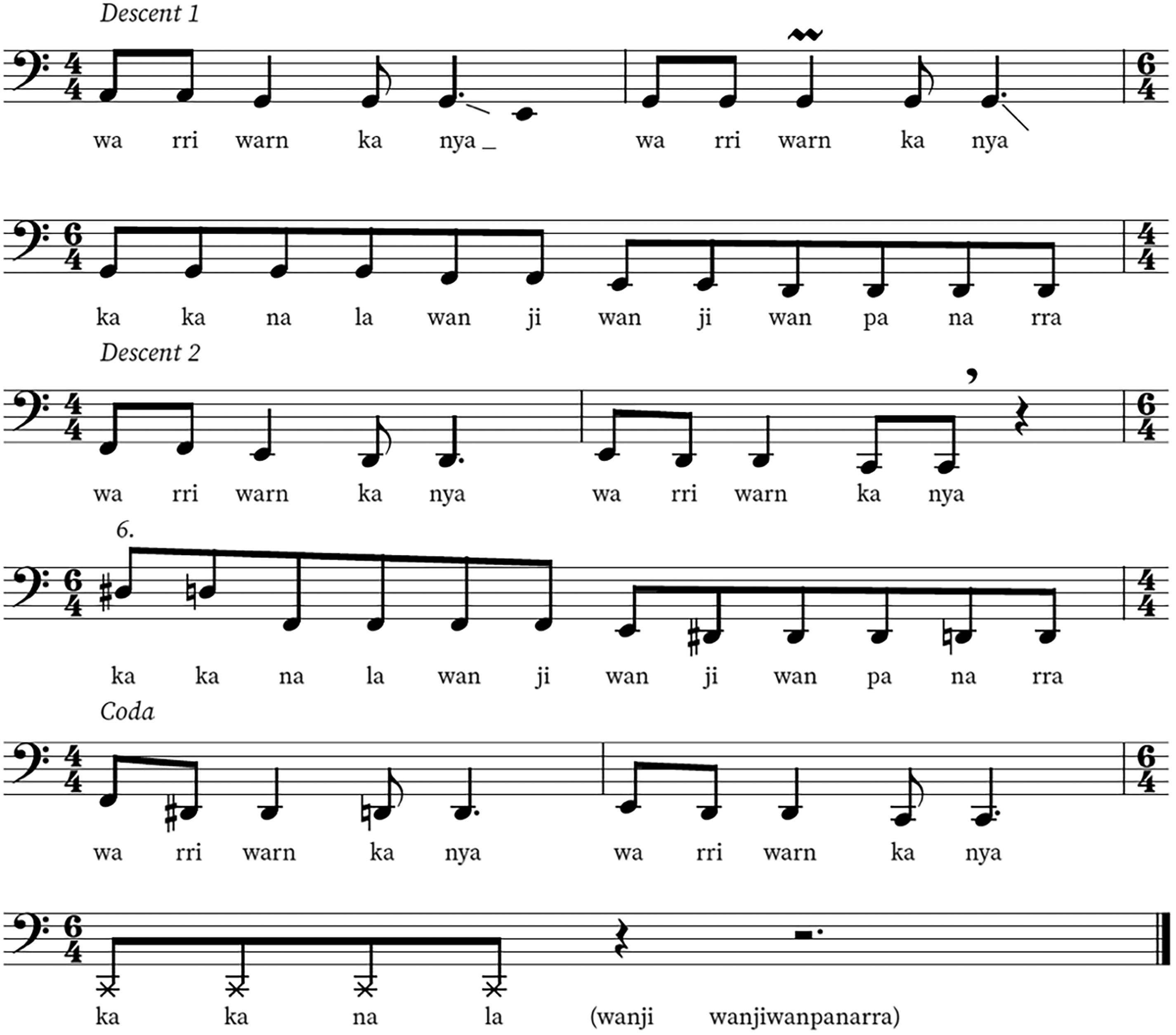

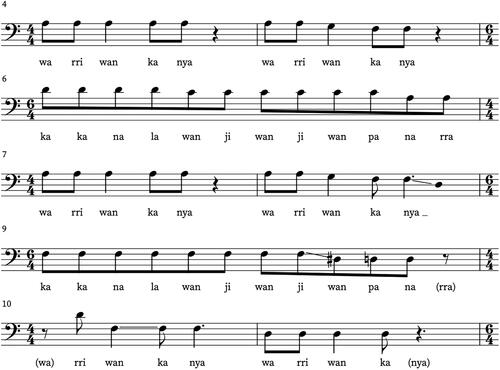

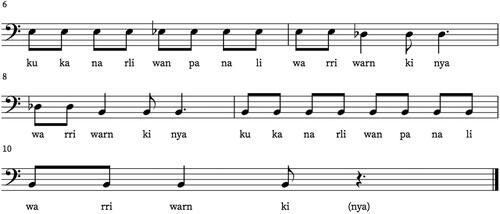

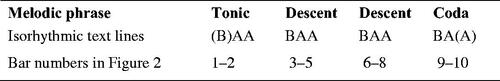

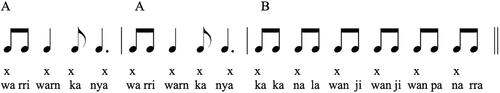

The lyrics of the Wanji-wanji are set to the fourteen-beat isorhythmic pattern shown in . A specific rhythmic value is given to each syllable of a word, resulting in an identical number of syllables and rhythmic notes. If we regard a Line to be the smallest repeating unit of such a rhythmic text, the Line pattern of this song is AAB: an eight-beat Line couplet (AA) followed by a final six-beat Line (B).

Figure 2. AAB Structure of the Wanji-wanji song. Note: Crosses (x) represent regular clap beats that usually accompany its singing.

The complete isorhythmic text is made up of a four-beat rhythmic-text pattern that repeats (Lines AA), followed by a six-beat pattern (Line B) and a terminal seventh clapped beat. The lack of rhythmic contrast across these twelve syllables/notes creates metrical ambiguity. Can they be heard as six groups of two quavers, three groups of four quavers or two groups of six quavers? Unlike Line A, Line B ends a crotchet short, creating a driving rhythm that pushes back to Line A. The two variants discussed earlier (recordings 2–3) have a Line B of eight quavers instead of twelve. Most song items recorded commence at the beginning of this structure. However, two commence at the beginning of Line B and one commences with the second last syllable of Line B.

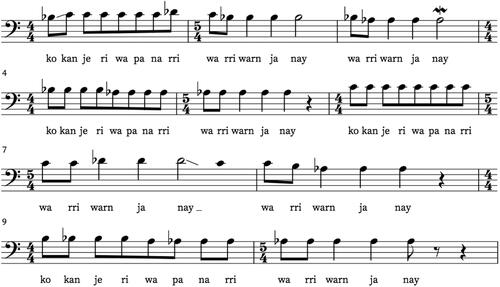

Musical Features of Wanji-wanji Song Items

A Wanji-wanji song item is an isorhythmic text sung repeatedly without interruption until the end of a longer melody, after which a short pause is taken and a new song item is begun (Barwick Citation1989, 13). In this section, we analyse the musical features of twenty-nine song items of the Wanji-wanji song recorded between 1967 and 2018. These include the twenty-four song items listed in , plus five song items from two interviews in 2017 and 2018 in which Pitjantjatjara women sang in response to hearing archival recordings.Footnote13

A song item commences with a solo singer, who clearly articulates the text and establishes the pitch and tempo. Presumably, this helps the group to know where in the isorhythmic text the singer is starting. Other singers present then gradually join in, so that by the second iteration of the isorhythmic text the whole group is singing predominantly in unison, but with occasional heterophony.Footnote14 After about twenty seconds, at a point in the lowest register, a song item begins to peter out. As the final syllables are performed, it is almost impossible to discern pitch. A song item concludes with a final clapped beat that signals its end. Subsequent repetitions of a song item are usually sung at the same pitch within a semitone variance, which probably reflects the vocal range of the lead singer.Footnote15

Duration, Tempo and Cycles of the Isorhythmic Text

The shortest song item in this corpus lasts nine seconds and the longest lasts just over one minute. The number of iterations of the isorhythmic text also varies across the twenty-nine song items analysed. The fewest number of iterations is two and a half and the greatest is eleven. This can be seen in , where we compare the number of iterations of the isorhythmic text within a song item (column 1) against four other features: duration (column 2), tempo (column 3) and solo or group performance (column 4). Finally, singular song items that were recorded as rememberings, as distinct from full performances, are shaded in .

Table 2. Comparison of the number of iterations of the isorhythmic text, duration, tempo and group/solo performance across the twenty-nine song items

As can be seen, the duration of a song item is longer when there are more iterations of the isorhythmic text and shorter when there are fewer. For song items with the same number of iterations, the shortest are those at a faster tempo. For example, of the song items with 2.5, 3 and 3.5 iterations of the isorhythmic text, those by Bill Harney (, 2008BH) are the fastest and shortest. Whether a song item is a remembering or from a fuller performance, or sung solo or by a group, appears to have little bearing upon duration. It is perhaps notable that the earliest recorded performance from 1967 is also the longest.

There is a tendency for song items within the same performance to have a similar number of iterations of the isorhythmic text. The eight song items performed by Wardaman elder Bill Harney (, 2008BH) have between 2.5 and 3.5 iterations. The six song items performed by the Pintupi group (, 1975PIN) have 2.5, 3.5 or 4.5 iterations. The 2015 and 2016 Gurindji group performances in Kalkaringi have 5.5 iterations in all but one item (, 2015/2016GUR), suggesting that that the number of iterations of an isorhythmic text per song item may be a regional feature. However, if we take both Pintupi performances into account (, 1975-NT and 1975PIN), we find no correlation between iterations and region.

The tempo of song items ranges from 147 to 194 beats per minute. Once again, there is a relationship between the geographic extremities of the recorded items and tempo. The variant items sung by Bill Harney, Robin Graham and Sam Dabb are at a faster tempo of 166 beats per minute or more, while all the others are slower than 160 beats per minute. Harney’s 2008 performance showed a consistency of tempo, number of isorhythmic text iterations and duration. No relationship was found between the presence or absence of clapped accompaniment.

Melodic Contours

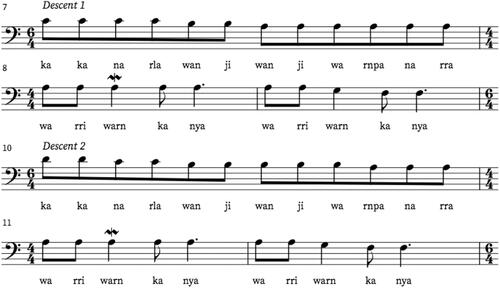

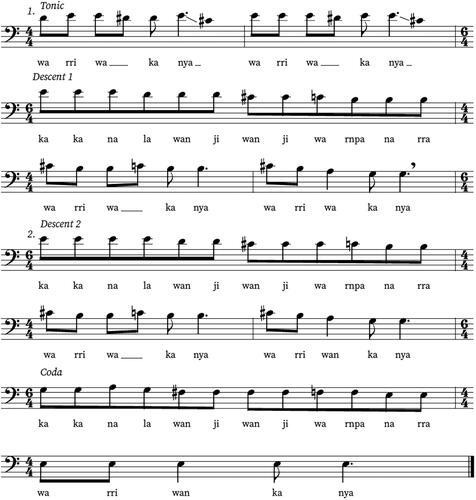

The melody comprises two or more descents that we call melodic contours. In addition, the melody comprises distinct phrases that we call sections. A new melodic contour starts when there is an upward leap in pitch of an interval of a fourth or more, which usually, but not always, coincides with a breath intake. shows a song item with two melodic contours. Each melodic contour is marked with a sequential number in italics at the top of the line. The first melodic contour descends a sixth (E–G) and the second begins after an upward leap of a sixth to the tonal centre, E and descends an octave.

Figure 3. A Song Item with Two Melodic Contours (, 1975PIN-01).

Note: The boundary between the two contours is marked by a leap in pitch and a breath. The tonal centre is E.

Most song items have two melodic contours, as in , or just one. The greatest number of melodic contours in a song item is six, while three and four are also evident. groups song items by their numbers of melodic contours. Song items within a performance tend to have the same number of melodic contours as well as the same number of iterations of the isorhythmic text, as noted earlier.

Table 3. Number of melodic contours across the twenty-nine song items

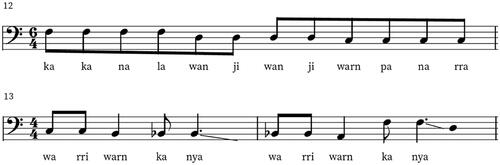

In most song items, melodic contours are easily identified. However, in three song items, all by solo singers, this is more difficult. A feature of Harney’s performance is that all song items are performed in one breath and all but one has a single melodic contour (see , 2008BH-04). In this song item, there is an upward leap of a fourth between D and G flat, but no corresponding breath intake (see ).

Figure 4. A Leap of a Fourth Between the Last Note of Bar 6 and First of Bar 7 to Start a New Melodic Contour (2008BH-04).

In song item 2017-NP-03, there are many rests that do not correspond with an upward pitch leap (). This variation may be due to this performance being a remembering of the song during an interview rather a full performance.

Dabb’s song item has a very different melodic structure and it is not possible to identify melodic contours as here defined. His song item is discussed later in the section ‘Exceptions to the standard organization’.

Melodic Phrases

The melody is made up of three different melodic phrases that we refer to as the Tonic, Descent and Coda. A melodic contour usually corresponds to two melodic phrases. The first melodic contour of a song item typically comprises the Tonic and Descent. The next melodic contour of a song item typically comprises the second Descent and Coda phrases. This structure can be repeated, as discussed in the following. We first outline the characteristics of each melodic phrase and then consider how these are organized in a song item. We then discuss two variants: the performances by Bill Harney and Sam Dabb.

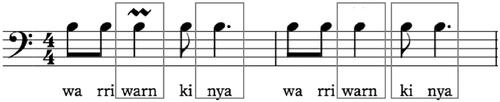

Tonic Phrase

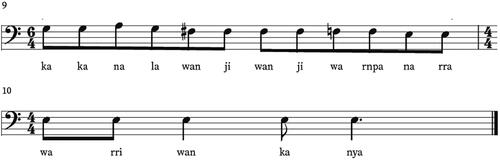

This consists of a repeated tonal centre with an ornamented stepwise pitch rise. It is set to Line A: Warri warnkanya. The first note is sometimes approached by a short upward or downward pitch inflection, which could result from singers finding a comfortable pitch to begin. An upward melisma is typically on the third syllable, ‘warn’. The final syllable, ‘nya’, a long note, slides down to a pitch somewhere between a second and a fourth. This full pattern repeats. Thus, the Tonic phrase consists of two near-identical halves. As shown in , the tonal centre E is approached by stepwise upward movement from D, a melisma occurs on the syllable ‘warn’ (F#) and the final note of the line slides down a minor third from the tonal centre E to C#.

The Gurindji often step up a second on the syllable ‘ka’ instead of ‘warn’ and, on the final note, slide down to a fourth instead of a third. This can be seen in , where the step up to G occurs on ‘ka’ as circled, and the final syllable, ‘nya’, slides down a fourth (F–C) instead of a third.Footnote16

Harney often sings a mordent (upper or lower) rather than a step up and omits ornamentation on the line-final syllable. This can be seen in , where there is a mordent in the first iteration of the Line, but not when it is repeated. There is no terminal line ornamentation. Perhaps relevant here is that Harney’s performance is at a much faster tempo (192 beats per minute), which may make it difficult to produce ornamentation.

In one of Harney’s song items, each pitch is repeated for five syllables. This is illustrated in , where the first iteration of Line A is on the tonal centre, B, followed by an upward step to C#.

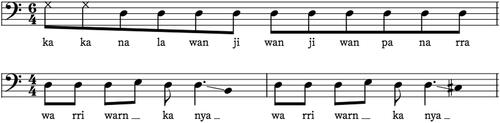

The Tonic phrase can also commence with text before Line A.Footnote17 This is shown in (, 1975-NT-01), where the text begins with wanpanarra which is the text from the end of Line A. Here, the downwards approach to the tonal centre (D) is noteworthy. The final syllable of this Line, ‘nya’, slides down a major second, rather than a third. As in the standard Tonic phrase, the upward step occurs on the syllable ‘warn’.

In some song items, the Tonic phrase occurs within a song item as discussed further in the following. In this position, it is similarly preceded by text from the previous line, and the repeated tonal centre approached from above. This is shown in , where Line B precedes the Line A couplet. The tonal centre, D, features throughout. However, it commences with a downwards movement to D set to Line B, Kakanala wanji-wanji wanpanarra, making it twice as long as the first Tonic phrase.

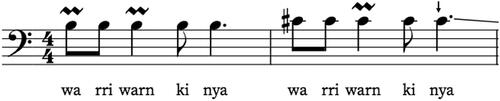

Descent Phrase

The Descent phrase typically descends stepwise from the tonal centre to a repeated fifth and then descends further, usually by a minor third. The Descent is set to a full cycle of the isorhythmic text over three bars in the present transcription (BAA). The Descent phrase repeats and, although the Tonic phrase is similarly made up of two near identical halves, we refer to each half of the Descent as separate phrases to better illustrate the relationship between melodic phrases and melodic contours. In most song items, the first Descent starts on the seventh, while the second Descent starts on the tonal centre. This is shown in , where the first Descent commences on the seventh, C, and the second Descent commences on the tonal centre, D, in bar 10. The descent to the minor third, F, in bars 9 and 12 is a striking feature of this phrase, as up until this point in the melody there has been no third.

In the Gurindji performances, the minor third interval is not always reached and is sometimes closer to a major third. ‘Warn’, for example, in bar 14 of is a major third rather than minor third above the tonal centre, F. The final iteration of Line A, Warriwarnkanya, is sometimes sung on the tonal centre at a higher pitch. This is shown in , which shows a Descent from the tonal centre, F, to a repeated fifth (C), down to the third (A) and then back up to the tonal centre, F.

Coda Phrase

The Coda descends to a repeated tonal centre. The descent is typically from the third, G, and moves by step. It is common for a song item to finish before the full cycle of the song, as illustrated in .

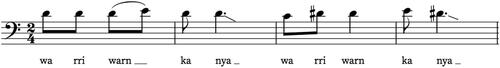

In Harney’s performances, the Coda commences on the fourth, E, and descends to the tonal centre, B. The repeated tonal centre extends for an additional two lines (BAABA). This is shown in , commencing on the fourth, E, and descending to the tonal centre, B, which repeats for an additional two lines over bars 9–10.

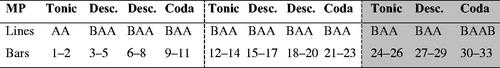

Organization of melodic phrases

In most cases, a song item is structured Tonic–Descent–Descent–Coda, such as 1975PIN-01 in . This structure is summarized in . Parentheses indicate that this line is optional and can be extended. This reflects flexibility about where in the isorhythmic text cycle a song item can start and end. As can be seen, all melodic sections end with a repeat of Line A. Seventeen song items follow this structure,Footnote18 with some extending or omitting phrases at their edges.Footnote19 We firstly illustrate how these melodic sections combine in most song items as a standard setting and then discuss exceptions to this.

In six of the seventeen song items with a standard structure, the whole melody repeats, making these items much longer than the others (1967-SY, 1970-RG, 1976PIN-03, 1975-NT-01, 1975-NT-02, 2018-PM-14). For example, Robin Graham repeats this structure, but sings only one Descent in the repeat instead of two. This can be seen by comparing the Descents in .

Sambo Yunimpuka’s performance (1967-SY) is even longer, with three iterations of the melody. His version similarly has only one Descent in the final iteration of the melody. A musical transcription of this song item, the longest song item in our corpus at a duration of one minute and one second, is given in Appendix 1. In four song items where the melody repeats, the final iteration of the melody commences on the tonal centre an octave below its starting pitch. A schematic structure of Yunimpuka’s performance is shown in with shading on the final iteration of the melody, which commences on the tonal centre an octave below. This song item’s ambitus spans nearly two octaves.

Exceptions to the Standard Organization

Eleven song items have only one Descent and these include all but one of Harney’s song items.Footnote20 As we have seen, this is also the structure used in the final iterations of the melody in longer song items, such as that shown in . The song item sung by Nyungar man Sam Dabb, however, differs much more significantly (1970-SD). The isorhythmic text line of this song item is structured as BAABABAABAABAAAAABA, which is a significant variation from the standard repeating AAB structure heard in other song items. The small pitch range of a fourth in this item is also unusual. Another unusual feature is the frequent crotchet rests, which renders the notion of melodic contours and melodic sections somewhat redundant. Instead, it appears to be a repeating melodic phrase broadly structured on the scale degrees 3–4–2–3–2–1 around the tonal centre (see ).

In summary, the melody of the Wanji-wanji song usually aligns isorhythmic text lines with melodic phrases, melodic phrases with melodic contours, and the lower octave singing of the melody with the final repeat of the whole melodic structure. The two most divergent performances are those by Bill Harney and Sam Dabb from the respective northern and southern extremities of its performed geographical reach. Harney’s singing consistently has a single Descent, while Dabb employs a small ambitus, a single broad melodic phrase that repeats and a flexible pattern of Line repetition as opposed to the repeating AAB structure. As discussed earlier, Dabb’s departure from this melodic norm could be the result of his imperfect memory of his mother’s singing. While he was a strong speaker of the Nyungar language, Dabb’s family did not necessarily consider him a singer. His elder brother, Charlie, confidently shared a larger repertoire of songs with the anthropologist/linguist C.G. von Brandenstein in 1970 that all employed a far wider pitch range (Bracknell Citationforthcoming).

Ornamentation

As we have seen, downward pitch slide is a common feature of the final note of Line A, ‘nya’, as circled in .

A form of ornamentation that is found exclusively in Pintupi performances is the use of an upper mordent-like melisma on the syllable ‘warn’. This typically occurs when the following syllable is the same pitch. This is illustrated through the slur in bar 1 of .

Conclusion

Wanji-wanji is recognized as the same song across a vast area spanning dozens of language-speaking communities. Our analysis finds that there is variation in melodic organization, duration, tempo and ornamentation of the song, but that the text, rhythm and melodic phrases are essentially the same across all communities. The Wanji-wanji song has a stable isorhythmic text with only two variants that result from reinterpreting the complex AAB verse form as AB verses of equal duration. In the case of Nyungar adaptation, the words are slightly altered, perhaps deliberately, to suit the local context.

The two lines of the isorhythmic text contrast in their number of syllables and rhythm, with Line A ending on a long note and Line B ending on a short note in all twenty-eight song items. The tonal centre is generally maintained within a performance but varies across iterations by different singers, suggesting that the pitch is determined by the preference of the performers. A variation in duration is heard across the corpus with song items being as short as nine seconds and others as long as a minute. The more iterations of the isorhythmic text and melodic contour within a song item, the longer it is in duration. These differences are also reflected in the range of isorhythmic text repetitions from 2.5 to 11 and the varying durations of song items (see ). Song items within a performance tended to yield the same number of iterations of the isorhythmic text, and this suggests that the number of iterations could be a regional feature.

Song items that were performed more recently tended to be slower in tempo, possibly reflecting the older ages of singers and their decreased performance opportunities. Bill Harney’s performance, in the north of the region, is one exception. A similar descending melodic contour and three distinct melodic phrases occur in all but one song item. There is a strong preference for two melodic contours per song item with Harney’s singing being the only exception of a performance with a preference for one melodic contour.

However, variation can be seen in the organization of these melodic phrases and their number of repetitions. For example, the Gurindji do not always end with a Coda. There are differences in ornamentation across some of the performances, with the Pintupi performances including many more melismas and Harney using a mordent style of ornamentation. Most song items featured the use of downward pitch slides, particularly at the end of Line A or at the end of a melodic phrase. Ornamentation highlights the edges of these structural units and foreshadows the beginning of a new melodic contour. Differences in ornamentation may thus be a regional feature.

Recent Aboriginal song revitalization projects draw on archival audio recordings and work with the descendants of recorded singers to develop processes to share and ultimately perform repertoire captured in archival collections that have not been recently sung (Bracknell Citation2019). Much of this material is inherently regional and families of deceased performers are understandably wary of sharing songs widely, even if songs were not culturally restricted in the past.

As a piece of ‘open’ unrestricted repertoire with a continuing history of performance across many Aboriginal communities, and even among non-Aboriginal people, the Wanji-wanji song has incredible potential to be revived in many communities and may again serve as a unifying force. Some of this work has already begun in the Nyungar region (Bracknell Citation2020).

In this study, we have identified the similarities and differences in the main song from the Wanji-wanji ceremony that was known throughout much of Australia. It is hoped that an understanding of the structures underlying this song and the many ways they can be combined in performance will help Indigenous people revive songs in creative ways beyond the act of memorizing a song item as recorded. Flexible processes that underpin performance, such as the alignment of different parts of the melody and isorhythmic text, ornamentation, tempo and duration, may be explored and chosen to reflect a regional style with which a performer may identify.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the custodians who gave permission for us to use the recordings listed in Table 1: Sony Graham (recording 1), Annie Dabb (2), Salote & Emma Bovoro (3), Barbara Hale (4), Ginger Wikilyiri (5), Linda Anderson (6), Elizabeth Marks and descendants at Kintore (7), Bill Harney (8) and Topsy Dodd and Jezebel & Kira Dandy (9 & 10). We thank the 175 Aboriginal people interviewed about their knowledge of the ceremony and the singers, the twenty researchers who assisted in the field as interpreters, introducing the authors to people, liaising with communities, and sharing their recordings and knowledge of the singers.

Disclosure statement

The Wanji-wanji ceremony and song described in this article is the cultural heritage of many Aboriginal people. Consent for the authors to talk and write about this song was given by many Indigenous consultants, whose written agreement is documented as part of ethical clearance obtained from the University of Sydney (2015/081, 2015/544). Permits for this research were obtained from the Ngaanyatjarra Council and the Central Land Council (51332, 41434, 30791). The ceremony should not be reproduced, published or performed without observing the protocols of attribution to the Aboriginal custodians described here and on the recordings; and the sharing of benefits with their communities.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Myfany Turpin

Myfany Turpin is an Associate professor at Sydney Conservatorium of Music, the University of Sydney. She has written a dictionary of the Australian Aboriginal language Kaytetye and documented traditional music of the Kaytetye, Alyawarr, Anmatyerr, Arrernte, Warlpiri and Gurindji peoples of the Northern Territory, Australia. She has published scholarly articles in music, semantics, phonology and ethnobiology; and has produced multi-media resources on language learning and Aboriginal songs.

Calista Yeoh

Calista Yeoh is an MA student in musicology at Sydney Conservatorium of Music, the University of Sydney. Her Honours and Master‘s research focuses on the musical structures and analysis of central Australian Aboriginal songs. She is the co-author of ‘An Aboriginal Women‘s Song from Arrwek, Central Australia’ in Musicology Australia 41, 1–27. Her transcriptions and musical analyses of Aboriginal songs have appeared in numerous publications, in collaboration with communities, linguists and ethnomusicologists.

Clint Bracknell

Clint Bracknell is a musician and researcher from the south coast Nyungar region of Western Australia. He holds an Australian Research Council fellowship as Associate Professor at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts and Kurongkurl Katitjin, Edith Cowan University. Clint recently co-translated a complete Shakespearian theatre work and a dubbed feature film in Nyungar, both world-firsts for languages of Australia. He received the 2020 Barrett Award for Australian Studies and is an elected AIATSIS Council member.

Notes

1 We acknowledge Fred Myers, Joe Brown and David Stock, in particular, as people interviewed who proposed this as a significant factor in the declining popularity of the ceremony.

2 The Manyjiljarra dictionary (Burgman Citation2009, 72) has ‘wana-jarra’ as meaning ‘woman’; literally ‘digging stick-with’.

3 Steven Stuart is a Karajarri and Nyangumarda man of Milangka skin who also speaks Nyamal. Interview archived at PARADISEC.

4 David ‘Yandi’ Stock is a Nyiyaparli and Banyjima elder of Milangka skin.

5 Kukatja and Mardu man, the late Patrick Tjungarrayi Ooladoodi, 17 July 2017 at Kiwirrkura, Western Australia. Wardaman man Bill Harney in telephone conversation with author Myfany Turpin, 31 May 2020.

6 Interview with Pantjiti McKenzie, 11 May 2018, Docker River. The name is also on the spine of the 1987 VHS recording made at Ernabella (see Table 1).

7 Wanji-wanji was probably known throughout the mid-west and wheatbelt areas of Western Australia. However, we have not interviewed people in this area. The contexts in which people encountered this song are diverse, from stock camps and droving to traditional ceremonial occasions and on missions and reserves. Such a history is too large to be considered here and is part of a larger forthcoming publication.

8 The Wanji-wanji song is also the sole song of the ceremony cited in Bates’s (Citation1938) The Passing of the Aborigines.

9 At Wallal Downs Station on the west coast, Nyangumarda elder Janet Stewart recalls that the station owner’s daughter, Annabelle Lacey, still knows this song from a childhood of attending corroborees.

10 The two documentary films are The Song Keepers (Sen Citation2017) and Milpirri: Winds of Change (Carter Citation2014).

11 A total of 175 people were interviewed between 2016 and 2020 by authors Myfany Turpin and Clint Bracknell.

12 This was confirmed to the authors by Henry and Annie Dabb, the son and daughter of the recorded singer Sam Dabb.

13 Nellie Patterson’s song items are rememberings (2017-NP) whereas Panjiti MacKenzie’s (2018-PM) are from a thirty-minute performance of twenty-six items, comprising eleven different songs in the Wanji-wanji ceremony with singing partner Tjukapati James.

14 Unison with occasional heterophony is common in Central Australian Aboriginal singing (Hercus and Koch Citation1995; May and Wild Citation1967, 210; Moyle Citation1979, Citation1986, Citation1997).

15 The Gurindji singers have a consistent tonal centre of F, Bill Harney has a tonal centre of B, Nosepeg Tjupurrurla and Pantjiti MacKenzie have a tonal centre of D and the Pintupi singers have a tonal centre of E.

16 Note that the precise pitch of the final point of this note is difficult to identify. The downward slide seems to be more important than the landing pitch.

17 Also see song items 2008BH-04 and 2018PM-13.

18 These song items are 1967-SY, 1970-RG, 1975PIN-01, 1975PIN-02, 1975PIN-05, 1975-NT-01, 1975-NT-02, 2015GUR-20, 2015GUR-21, 2016GUR-13, 2018-PM-12, 2018-PM-13, 2018-PM-14, 2017-NP-03, 2017-NP-04, 1970-OA and 1987-PIT. Recording of the latter we surmise commenced after the song had begun and thus what is heard is actually an internal Tonic section.

19 In various song items, the Tonic phrase is omitted (2018-PM-14), the Coda phrase is omitted (1970-OA) and the Coda phrase is extended (2016-GUR-13).

20 The variants are the eight song items by Bill Harney, 1975PIN-03, 1975PIN-04 and 2016GUR-12.

References

- Barwick, Linda (1989), ‘Creative (Ir)regularities: The Intermeshing of Text and Melody in Performance of Central Australian Song’. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 12–28.

- Bates, Daisy (1914a), ‘Daisy Bates Papers, Section XI, 1b, iv – Ceremonies, Corroborees, Songs, Ooldea District [Manuscript]’, Trove (Accessed 14 April 2021), http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/33784606?selectedversion=NBD42954719

- Bates, Daisy (1914b), ‘Daisy Bates Papers, Series 12, Section XI, 1A Dances, Songs [Manuscript]’, University of Adelaide (Accessed 14 April 2021), http://hdl.handle.net/2440/75018

- Bates, Daisy (1914c), ‘Daisy Bates Papers, Series 12, Section XII, 2G, 4 ‘Native Vocabulary’ [Manuscript]’, University of Adelaide (Accessed 14 April 2021), http://hdl.handle.net/2440/86906

- Bates, Daisy (1914d), Series 2.6. ‘Songs and Dances of the Last Wanji-Wanji – Eucla’, “Daisy Bates Papers MSS 572.994 B32t Series 2: ‘Native Testaments of old natives’.” [Manuscript]’, University of Adelaide (Accessed 14 April 2021), http://hdl.handle.net/2440/89390

- Bates, Daisy (1915), ‘Correspondence’. The Northern Miner. Charters Towers, QLD, 3 March.

- Bates, Daisy (1938), The Passing of the Aborigines. London: John Murray.

- Bracknell, Clint (2019), ‘Connecting Indigenous Song Archives to Kin, Country and Language’. Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, 20/2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/cch.2019.0016

- Bracknell, Clint (2020), ‘Rebuilding as Research: Noongar Song, Language and Ways of Knowing’. Journal of Australian Studies, 44/2: 210–23.

- Bracknell, Clint (forthcoming), ‘Reanimating 1830s Nyungar Songs of Miago’, in A. Harris, Jaky Troy, and Linda Barwick (eds.), Music Dance and the Archive. Camperdown: University of Sydney Press.

- Breen, Marcus (1989), Our Place, Our Music. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Burgman, Albert (2009), Manyjilyjarra to English Dictionary. Port Hedland, WA: Wangka Maya Language Centre.

- Carter, Stewart, dir. (2014), Milpirri: Winds of Change. Australia: People Pictures.

- Corroborees as Travelling Shows (1915). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842–1954), 17 February, 5.

- Girard, François, dir. (1998), The Red Violin [Le Violin rouge]. Toronto: Niv Fichman and Rhombus Media (distributed by Lions Gate Entertainment, Santa Monica California, USA).

- Harris, Amanda (2014), ‘Archival Objects and the Circulation of Culture’, in Circulating Cultures: Exchanges of Indigenous Australian Music, Dance and Media. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1–16.

- Hercus, Luise, and Koch, Grace (1995), ‘Song Styles from Near Poeppel’s Corner’, in L. Barwick, Allan. Marett, and Guy Tunstill (eds.), The Essence of Singing and the Substance of Song: Recent Responses to the Aboriginal Performing Arts and Other Essays in Honour of Catherine Ellis. Sydney: Oceania Publications, 106–20.

- Laughren, Mary (in press), Warlpiri to English Encyclopaedic Dictionary. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Marett, Allan (2005), Songs, Dreamings, and Ghosts. The Wangga of North Australia. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

- May, Elizabeth, and Wild, Stephen (1967), ‘Aboriginal Music on the Laverton Reservation, Western Australia’. Ethnomusicology 11/2: 207–217.

- Moyle, Richard (1979), Songs of the Pintupi: Musical Life in Central Australian Society. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Moyle, Richard (1986), Alyawarra Music: Songs in a Central Australian Community. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Moyle, Richard (1997), Balgo: The Musical Life of a Desert Community. Nedlands: CIRCME, The University of Western Australia.

- Rademaker, Laura (2016), ‘Why Historians Need Linguists (and Linguists Need Historians),’ in Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch, and Jane Simpson (eds.), Language, Land and Song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus. London: EL Publishing, 480–93.

- Sen, Naina, dir. (2017), The Song Keepers. Australia: Screen Australia, Indigo Productions, and Brindle Films.

- Stock, David (2018), ‘Interviewed by Myfany Turpin. 20180730’, PARADISEC (Accessed 14 April 2021), https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/MMT1

- Stuart, Steven (2019). ‘Interviewed by Myfany Turpin. 20190721’, PARADESIC (Accessed 14 April 2021), https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/MMT1

- Tomlinson, Gary (2007), The Singing of the New World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Treloyn, Sally (2014), ‘Cross and Square: Variegation in the Transmission of Songs and Musical Styles Between the Kimberley and Daly Regions of Northern Australia’, in A. Harris (ed.), Circulating Cultures: Exchanges of Indigenous Australian Music, Dance and Media. Canberra: Australian National University Press, 203–38.

- Turpin, Myfany (2019), ‘Return of a Travelling Song: Wanji-wanji in the Pintupi Region of Central Australia, in Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green, and Petronella Vaarzon-Morel (eds.), Archival Returns: Central Australia and Beyond. Sydney: Sydney Unviversity Press, 239–62.

- Turpin, Myfany, and Meakins, Felicity (2019), Songs from the Stations: Wajarra as Performed by Ronnie Wavehill Wirrpnga, Topsy Dodd Ngarnjal and Dandy Danbayarri at Kalkaringi. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

- Turpin, Myfany, and Stebbins, Tonya (2010), ‘The Language of Song: Some Recent Approaches in Description and Analysis’. Australian Journal of Linguistics 30/1: 1–17.

- von Brandenstein Carl Georg (1969–70), Papers of Carl Von Brandenstein, Diary XIX [Manuscript]. Canberra: AIATSIS.

- Winkler, Peter (1997), ‘Writing Ghost Notes: The Poetics and Politics of Transcription’, in David Schwarz, Anahid Kassabian, and Lawrence Siegel (eds.), Keeping Score: Music, Disciplinarity, Culture. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 169–203.

Appendix 1

Sambo Yunimpuka’s performance (1967-SY), G tonal centre.