Abstract

This article argues for the significance and impact of the Sousa Band’s 1911 Australasian tour on local musical practice, through the lenses of cultural dynamics, reception, and legacy. Set against growing nationalism in the years preceding the Great War, the Sousa Band’s thirteen-week tour was enthusiastically welcomed by Australian audiences and underscored by the band’s alignment with the growing popularity of ragtime music, itself a point of negotiation between Anglo-Celtic and US American cultural influence in Australia. The majority-woodwind instrumentation of the Sousa Band is contextualized within the shifting favours of the time, given Australian audiences’ greater familiarity with British-inspired all-brass band models, within which the Sousa Band’s use of saxophones presaged certain changes in local musical practice that would unfold over subsequent decades. The influence of John Philip Sousa’s concert programming and statements as a public intellectual are also examined to contend that, while never quite ‘highbrow,’ an underlying theme of cultural uplift contributed towards the tour’s enduring impression on a new generation of Australian musicians.

In March 1932, news of John Philip Sousa’s death prompted lengthy tributes and discussions of his legacy in the Australian press. Daily newspapers recounted how Australian audiences from the 1911 Sousa Band world tour had recognized the ensemble as a ‘remarkably well-trained organisation,’ with particular ‘talents in interpretation’ beyond the tuneful marches for which the March King was so widely known (Sydney Morning Herald Citation1932a, 9). In the musical press, the Australasian Band and Orchestra News memorialized Sousa on its cover, and fondly recalled the Sousa Band’s antipodean concerts within its pages:

The performances were marked by an extreme of virility, also by the chief’s spectacular showmanship, but Sousa was a craze and his … marches took a sturdy hold of everybody down to the innumerable small boys who whistled them in the streets. (Australasian Band and Orchestra News Citation1932, 3)

did a power of good to the bands of Australia by giving them new ideas of refinement, tone-colours, and interpretation which have since led them on to an ability to perform music that—quite frankly—was beyond the comprehension of the old-time bands. (Australasian Band and Orchestra News Citation1933, 2)

Yet this episode, and its reverberations, remain largely unexplored in scholarly terms. Bands were key fixtures of musical life in Australia’s long nineteenth century, but John Whiteoak observed that ‘Australian musicologists have tended to shun the study of brass banding as being somehow too lowbrow or prosaic for consideration’ (Citation2002, 27). Related but rarer ensembles, such as the woodwind-infused military or concert band, appear to have suffered a similar fate.Footnote1 Whiteoak, for his part, does not share such a view: in Playing Ad Lib he denotes organized banding as belonging to the ‘approved’ stream of Australian music-making, rather than the ‘anonymous’ alternative, on account of the social capital its rational recreation-aligned adherents accrued (Whiteoak Citation1999, xvi).Footnote2 The banding movement itself is also culpable for this absence to a degree: the editor of the Australasian Band and Orchestra News reflected that despite the regard in which Sousa was held, ‘veterans in the brass band world’ spoke less about the 1911 tour than visits from other international bands of the era (Australasian Band and Orchestra News Citation1932, 1).

Recent musicological discourse, however, suggests new relevance in examining this series of performances. Most notably, notions of cultural value have been challenged as scholars seek to complexify ideas of cultural hierarchy beyond the ‘lowbrow’ and ‘highbrow’ binary (Chowrimootoo et al. Citation2020, 327–34), inviting the reappraisal of formerly limiting frames. Familiar questions, such as how bands offered insights into the shifting favours of local musical practice and opinion, resonate anew; assertions of band music being an exclusively ‘lowbrow’ pursuit—perhaps too narrowly parochial, or otherwise insufficiently influential—are likewise open to critical study. Informed by findings from and beyond my doctoral thesis on the early history of the saxophone in Australia (Chapman Citation2023),Footnote3 this article contends that the Sousa Band’s instrumentation, spirit of cultural uplift, and tenacious hold on local cultural memory position its 1911 performances as a critical inflection point in twentieth-century Australian musical practice.

National Characters, Fears, and Favours

By the time of Australia’s federation with British institutions at its core, local ‘old-time bands’ (Australasian Band and Orchestra News Citation1933, 2) had become distinctly British in orientation, and, such was their ubiquity, ‘no outdoor public ceremony or festivity was complete without a band in attendance to add to the dignity or jollity of the occasion’ (Blythell Citation1997, 68). From his vantage point across the Pacific, and informed by three tours of Europe between 1900 and 1905, Sousa had long been expansive about his thought leadership on musical practice and understood bands as key expressions of national identities. Quoted in the Australian press in 1913, he described the particular meanings that could be imparted by a band’s instrumentation, initially citing German ensembles as an exemplar:

In every country bands take different characters—the band is all things to all nations—it is the most flexible, most elastic of all musical bodies. Partly, I think, it reflects in its composition the national character. The Germans, I suppose, are still a serious people—they have the solid virtues, and like good solid food, though they do drink light beer. Well, their band is a serious, solid band—its brass is tremendous, but its woodwind weak in comparison. The regulation number of instruments is forty-two; but it does not embrace saxophones and has only a small body of clarinets. (Bookfellow Citation1913, 240)

Australian audiences warmly welcomed touring all-brass bands, most strikingly during the 1907 visit of Manchester’s Besses o’ th’ Barn Band to Melbourne, where it was met by twenty-two local bands and thousands of onlookers on its procession up Collins Street (Argus Citation1907, 7). A notable exception to this prevailing format was heard shortly following the Federation, when Britain’s visiting Royal Marine Band presented two concerts remarkable to Australian audiences on account of their instrumentation: the first half of the performance was orchestral, featuring seventeen string players balanced by an equal number of brass, percussion, and woodwind; the second half saw string players revert to military band instruments in an evenly weighted band of brass and woodwinds, alongside two drums (Sydney Morning Herald Citation1901, 10).Footnote6

The Sousa Band presented another alternative model for Australian audiences. This was not only on account of the charismatic stylings of its leader and musicians,Footnote7 but its US heritage with significant French influence on its forebear organization, the prolific concert band led by Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore.Footnote8 Sousa described French bands in slightly unusual terms as being ‘like a French dinner—quite light in the brass’ (Bookfellow Citation1913, 241). Described variously as a military band, concert band, or wind orchestra (as Sousa preferred), with a greater relative number of woodwinds, this type of ensemble became known to some Australian audiences through formations such as the Sydney Professional Band, which sported up to forty instruments including a full complement of single and double reeds. The systematic incorporation of saxophones was one marker of this model, and on the cusp of the Sousa Band’s arrival the Sydney Professional Band included a saxophone section with soprano, alto, and two tenors among its number (Newsletter Citation1910, 2). Sousa opted for three saxophones in his ensemble (an alto, tenor, and baritone) among his regular complement of fifty-nine instruments,Footnote9 and noted of these instruments in particular:

Come to the saxophones—these are the ’cellos of the band, corresponding with the middle tones of the voice; Adolphe Sax devised them to give weight in the middle of the band. You hear them well in all the ’cello voices of the Meistersinger prelude, or in Tschaikowsky’s 1812 overture with its broad tonal effects. (Bookfellow Citation1913, 241)

Figure 1. Advertisement for Paling & Co. Australasian Bandsman (Bathurst), 7 February 1908, 36. Whiteoak Research Collection. Reproduced with the permission of John Whiteoak.

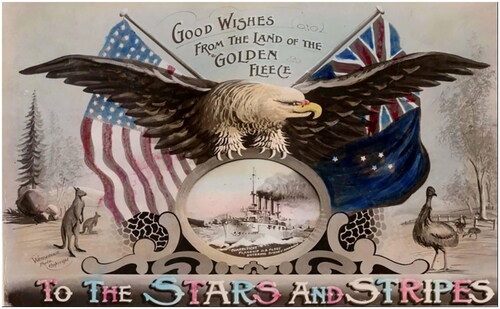

Beyond the strictly musical, band instrumentation of this period could also be considered to be functioning as a form of timbral entente, given rising nationalism and evolving political dynamics. While Australians prized their ties to Britain, Richard Waterhouse notes that accelerating US cultural influence encouraged a perception of the United States as a model of modernity ‘to define Australia’s political, social and economic future’ (Citation1990, 110–12).Footnote11 As German bands waned in esteem, and in a year when Kaiser Wilhelm II’s growing navy attracted widespread local comment and concern (Darling Downs Gazette Citation1911, 4),Footnote12 Australians enthusiastically welcomed the Sousa Band’s tour. Postcards were issued recalling the fond reception accorded to sixteen vessels of the US Navy’s Great White Fleet on its 1908 visit (see and ), when the United States was viewed as an ally against the emerging naval power of Japan. Sousa spoke to Australian newspapers of the lingering warmth from this earlier episode, with a reporter relaying: ‘If [Australians] treated [Sousa] as they had treated the American Fleet, he would go home with a swelled head’ (Clarence and Richmond Examiner Citation1911, 5). In lieu of hard power and battleships, the Sousa Band—an iconic cultural product from another liberal democracy across the Pacific—promised an exercise in soft power from the bandstand.

Figure 2. Postcard welcoming the Great White Fleet in 1908. Good Wishes from the Land of the Golden Fleece to the Stars and Stripes, ca. 1908. G. Wensemius. Australian National Maritime Museum, 0003810. https://collections.sea.museum/en/objects/45175.

Figure 3. Postcard welcoming the Sousa Band in 1911. ‘Australia extends the glad hand of Welcome to Sousa and his band,’ ca. 1911. PIC Album 998/594 A (PIC/4008), David Elliott Theatrical Postcard Collection [picture], National Library of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-145695597. Reproduced with permission of the National Library of Australia.

![Figure 3. Postcard welcoming the Sousa Band in 1911. ‘Australia extends the glad hand of Welcome to Sousa and his band,’ ca. 1911. PIC Album 998/594 A (PIC/4008), David Elliott Theatrical Postcard Collection [picture], National Library of Australia. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-145695597. Reproduced with permission of the National Library of Australia.](/cms/asset/1b3551a6-3f51-4fc8-ae83-a6381c2eec8f/rmus_a_2366042_f0003_c.jpg)

The Sousa ‘Craze’ and Cultural Uplift

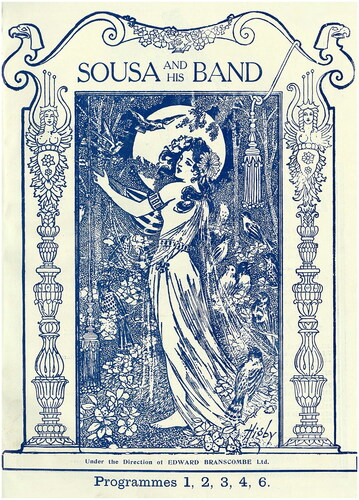

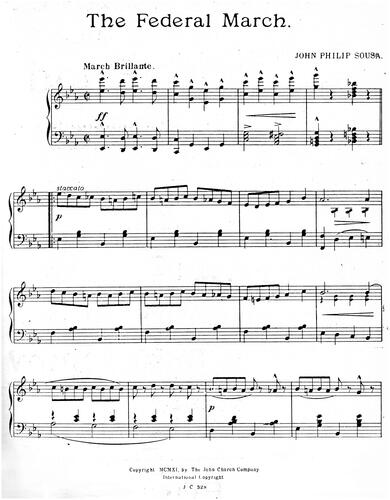

In December 1910, the Sousa Band commenced what was the most extensive tour ever made by such a large band to date, with an itinerary encompassing England, Ireland, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and Hawaii. Ironically for an ensemble led by a man who prized punctuality, a delay on arrival in Hobart on 11 May led to the cancellation of the Sousa Band’s first performance (Bierley Citation2006, 111), but engagements across Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia, New South Wales, Queensland, and New Zealand followed over a period of thirteen weeks. Within these performances Sousa often featured a piece especially composed for his antipodean audiences, The Federal March (1910—Dedicated to the Australasians), whose introduction and opening strain were printed in local programmes (Sousa Citation2018; see and ). Its title was originally to have been The Land of the Golden Fleece, in a nod to both nations’ thriving wool trades; however, The Federal March was suggested to Sousa by Sir George Reid, High Commissioner for Australia, who heard the march in London at tour’s outset (Bierley Citation1984, 51–52).Footnote13 Musically, The Federal March’s dextrous opening strain foregrounds woodwinds, characteristic of Sousa’s compositional approach. In his own telling, this differed from other ensembles ‘in the predominance of the wood instruments. … The leading instrument in a military band is the cornet; in my band, it is the B flat clarionet’ (Daily Telegraph Citation1911a, 6).

Figure 4. Concert programme cover from the Sousa Band’s Australasian tour, 1911. ‘Sousa and his Band. Programmes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6.’ Papers of Alex Whitmore (1906, 1911), UMA-ACE-19750065, University of Melbourne Archives. Reproduced with permission of the University of Melbourne Archives.

Figure 5. The Federal March, printed in concert programmes from the Sousa Band’s Australasian tour, 1911. ‘Sousa and his Band. Programmes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6.’ Papers of Alex Whitmore (1906, 1911), UMA-ACE-19750065, University of Melbourne Archives. Reproduced with permission of the University of Melbourne Archives.

After an earlier visit in May, the Sousa Band’s return to Melbourne in June saw it escorted by a mass of local bands down Collins Street to an official welcome at the Town Hall. Accounts of the size of this welcoming party vary: Andrew Bisset mentions forty bands, but the Melbourne press detailed seventeen bands as participating (Bisset Citation1979, 45; Argus Citation1911b, 7).Footnote14 Sousa Band tenor saxophonist Albert A. Knecht recorded in his diary that this was ‘the greatest reception given us by [Australian] citizens that the band ever received … about 300,000 people would be a safe estimate were standing by’ (Bierley Citation2006, 112–13). For Victorian audiences the Sousa Band performed in Melbourne’s Royal Exhibition Building, Southbank’s Glaciarium, Bendigo, and during two separate visits to Ballarat, Australia’s spiritual home of the banding movement and host of the South Street Society’s Grand Annual Eisteddfod of Australasia (Ballarat Star Citation1911, 8). Following the final Royal Exhibition Building performance, a Melbourne reporter provided a representative account of both the music and the audience response:

The programme was made up of the pieces that have proved most popular during the tour and encores followed every number. Three extracts from Wagner were magnificently rendered—the Bridal Music from ‘Lohengrin,’ a selection from ‘Tannhauser,’ and The Ride of the Valkyries. … A fine selection from Giordano’s ‘Andrea Chenier’ concluded the first part of the programme. Jahnfeldt’s ‘Praeludium’ went as well on the wind band as with the full orchestra, and several of Sousa’s marches were played with tremendous go and energy. ‘The Stars and Stripes’ was greeted with shouts of applause. At the end of the concert, after the National Anthem, ‘Auld Lang Syne’ was played, and cheers were given for Mr. Sousa. He said that he could not attempt to address such an audience without a megaphone. (Argus Citation1911c, 9)

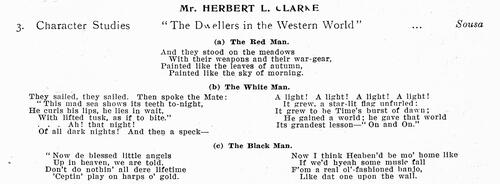

Figure 6. Selection from Programme no. 3 from the Sousa Band’s Australasian tour, 1911. ‘Sousa and his Band. Programmes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6.’ Papers of Alex Whitmore (1906, 1911), UMA-ACE-19750065, University of Melbourne Archives. Reproduced with permission of the University of Melbourne Archives.

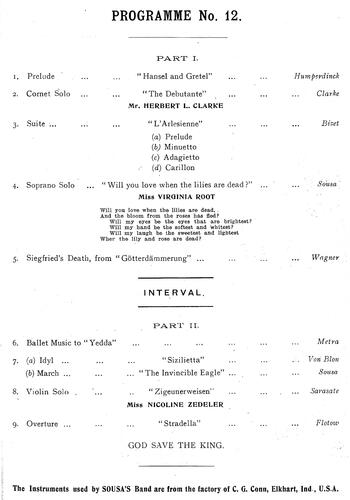

Figure 7. Programme no. 12 from the Sousa Band’s Australasian tour, 1911. ‘Sousa and his Band. Programmes 5, 7, 10, 11, 12, 20.’ Papers of Alex Whitmore (1906, 1911), UMA-ACE-19750065, University of Melbourne Archives. Reproduced with permission of the University of Melbourne Archives.

For Australian audiences, if banding was predominantly perceived as British, in the case of ragtime the US American influence held sway. Nevertheless, Whiteoak notes that competition between the two functioned as a ‘complex arena of negotiation between [US] American and Anglo-Celtic/Australian popular culture’ (Whiteoak Citation1999, 112). US American Ben Harney, marketed as ‘the originator of the now-popular rag-time dancing and music’ (Queensland Figaro Citation1911, 16), toured Australia from December 1910 to May 1911. Both Harney’s and the Sousa Band’s performances took place on the cusp of the ragtime’s ‘second phase’ in Australia, which was heralded by the 1911 publication of Irving Berlin’s ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band,’ widely heard locally from 1912.Footnote18 As Whiteoak notes, after this time ragtime songs were marked by an ‘unambiguous projection as “modern American music” … no longer [needing] to parody black vernacular’ in the manner of the cakewalks and ‘coon songs’ of earlier years (Whiteoak Citation1999, 118).

In other programmed items, the Sousa Band’s woodwinds enabled Australian audiences to hear rare European timbres, both real and imitated. Clarinettist Joseph Norrito earned acclaim for his solo work in Air Italien, with a Sydney reviewer noting how ‘patrons and admirers of the band were well pleased at the opportunity’ to hear a woodwind soloist from such a renowned ensemble (Sun Citation1911b, 1). After another Sydney performance, a critic relayed how members of the twenty-one-strong clarinet section ‘deftly suggested the pizzicato of the Spanish guitar and other plectral instruments,’ leading to the comment that the Sousa Band’s woodwinds ‘might well serve as an object lesson to most performers whose earnest wish it is to excel at their various instruments’ (Sun Citation1911a, 5).Footnote19

Saxophonists also made several noteworthy contributions.Footnote20 On 30 May 1911, Sydney’s Town Hall audience was privy to an alto saxophone solo in Bizet’s L’Arlésienne Suite no. 1 (see ), which includes a famed passage in its Prélude. This so-called ‘L’innocent’ theme, which has been performed often enough to be considered ‘the best-known saxophone solo of all time’ (Harvey Citation1995, 61), belongs to a work that had enjoyed remarkable popularity in France since its eponymous play’s 1885 revival.Footnote21 Bizet’s original inclusion of the saxophone sat alongside a number of evocative instrumental choices unusual for an orchestral palette from its time, such as the tambourin, a long cylindrical drum intended to enhanced the Provençal flavour of the play (Macdonald Citation2014, 346). In Australia, Sousa’s instrumentation offered a degree of greater fidelity to Bizet’s intentions than earlier renditions: L’Arlésienne Suite no. 1 had been first performed in Melbourne as part of Frederick Cowen’s orchestral performances at the 1888–1889 Centennial Exhibition, but Cowen’s instrumentation did not include saxophones (Australasian Citation1889, 51). In Sydney, this melody rose above an ensemble credited in a review as playing with ‘all the admirable balance, delightful modulations, and effective tone which have characterized its performances all the way through [its tour]’ (Daily Telegraph Citation1911b, 10). Saxophonic novelties also featured in Melbourne, where audiences were treated on 20 June to the use of cloth-muted saxophones for a section of the band’s realization of the Largo from Dvořák’s Symphony no. 9 in E minor, ‘From the New World’ (Bierley Citation2006, 113). Precise meanings encoded in Bizet’s melody for the Sydney audience, or imbued from Dvořák’s harmonies in Melbourne, ultimately remain conjectural, absent more specific commentary; however, ahead of his first European tour, Sousa had advocated: ‘It is very important that [saxophones] should be introduced, because [they] make easily possible a register which was before extremely difficult’ (Citation1900, 233).Footnote22

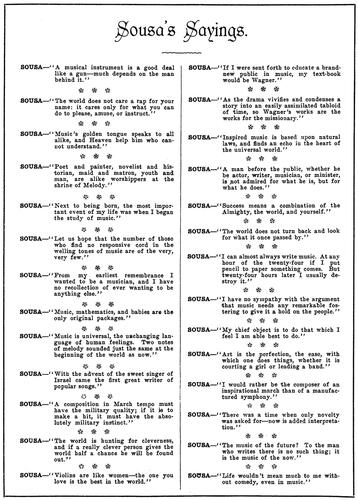

While these performances were ephemeral, their impact may not have been. In line with Sousa’s standing as a public intellectual, concert programmes included a full-page collation of ‘Sousa’s Sayings’ (see ), one of which asserts: ‘I have no sympathy with the argument that music needs any remarkable fostering to give it a hold on the people.’ Other sayings stress the importance of Wagner’s music to Sousa’s work, and encourage the examination of these concerts through a more elevated cultural lens. Two quotations speak to this tie directly; namely, ‘If I were sent forth to educate a brand-new public in music, my text-book would be Wagner,’ and ‘As the drama vivifies and condenses a story into an easily assimilated tabloid of time, so Wagner’s works are the works for the missionary.’ Of twenty-seven sayings, only these two mention any composer by name, as part of a feature included in programmes throughout the Sousa Band’s world tour (Danner Citation1998, 17). A third saying also hints at a connection: ‘The music of the future? To the man who writes there is no such thing; it is the music of the now’ (see ).

Figure 8. ‘Sousa’s Sayings’ from the Sousa Band’s Australasian concert programmes, 1911. ‘Sousa and his Band. Programmes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6.’ Papers of Alex Whitmore (1906, 1911), UMA-ACE-19750065, University of Melbourne Archives). Reproduced with permission of the University of Melbourne Archives.

By 1911, Wagner’s music had been impressing antipodean audiences for decades. Indeed, Sousa’s Wagnerian associations resonated well, given the veneration accorded to Wagner’s operas since their local introduction in 1877 (Waterhouse Citation1995, 139), when the staging of Lohengrin in Melbourne prompted calls that it ‘may be said to mark the commencement of a new era in music in these colonies … never has a larger or more intelligent audience attended to witness a performance’ (Age Citation1877, 2). However, such were the costs of staging this grand opera, compounded by the need to keep prices low to attract audiences, that the enterprise’s financial failure deterred theatre managers from staging Wagner’s operas for years hence (Waterhouse Citation1995, 135). Despite exceptions, such as in 1905 when Melburnians created a subscription list to fund the tour of a company that would perform Wagner in German (which occurred in 1907; see Murphy Citation2014, 82), this state of affairs created a degree of scarcity on the Australian stage; in ‘highbrow’ minds, the more familiar Italian operas were considered frivolous, and Wagner a ‘true genius of the genre’ (Waterhouse Citation1995, 136). Elsewhere, Wagner’s connection to home-grown Australian art music could be found in George Marshall-Hall’s self-identification with Wagnerian-style music. As Peter Tregear notes, Marshall-Hall’s Symphony in E flat of 1903, ‘composed in part during camping trips with Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts and other artists of the so-called “Heidelberg School,” [demonstrates] how Wagnerian musical rhetoric and style could be appropriated and adapted to serve an Australian context’ (Tregear Citation2014, 73). Sousa’s medium ensured Wagner’s music was both artistically well-realized, and disseminated in a more popularly appealing form than some earlier local iterations.Footnote23 Midway through the tour, Sousa elaborated on this connection in an interview with a Sydney journalist:

I can claim the credit of playing more Wagnerian music than any other bandmaster. With the exception of ‘Rhinegold’ and ‘The Flying Dutchman’ we have included in our Sydney programmes selections from all Wagner’s operas. Think of that. Don’t let anyone say that I came all the way to Australia to make money at the sacrifice of art. I shall be a disappointed man if the tour of my band does not help to raise the standard of musical taste and musical appreciation in Australia. A first-class band playing good band music is just as much an education of the public as grand opera is, or a symphony orchestra. (Referee Citation1911, 15)

Instead, from the view of recent scholarly discourse, the Sousa Band satisfies a number of criteria to be more appropriately considered ‘proto-middlebrow.’ The middlebrow in music, occupying an intermediate space between binary ends of cultural taste (the ‘lowbrow’ concerned with entertainment, commercialism, and the mass market; and the ‘highbrow’ appertaining to elitism and difficulty), had its adherents famously coined in Punch as ‘a new type, the “middlebrow”: people who are hoping that some day they will get used to the stuff they ought to like’ (Punch Citation1925, 673). More recently, Christopher Chowrimootoo and Kate Guthrie offered three key measures for the musical middlebrow: artists, educators, and concert programmers who sought to democratize access to high art; a target audience, particularly those who consumed culture for its social and intellectual capital; and cultural products that combine elements of ‘serious’ and popular culture (Chowrimootoo et al. Citation2020, 328). Sousa’s local performances, in which a concert band rendered both art and popular music as part of an espoused mission to educate its audience, most evidently validate the first and third of these criteria.

However, the picture is less clear on the question of a target audience, constrained by the limited development and thus influence of the mass market in Australia at the time. Although phonograph recordings were widespread in 1911, it was the local introduction of commercial radio (ca. 1923), the recording industry (ca. 1925), and sound film (ca. 1929) that would serve to develop the mass market more comprehensively in the following decade. During the tour, Sousa spoke of Australians as being ‘just the sort of audiences I like’ (Referee Citation1911, 15), but subsequently described them—as with audiences elsewhere—as belonging to either end of the spectrum:

I don’t find the audiences differ greatly—in America, Europe, Australia. It’s my experience that about five percent of an audience come out of curiosity; ninety-five percent come because they are fond of music. Of course, the standard of musical knowledge varies, so I try to vary my programmes so as to suit all classes—getting as much as possible on a common ground where the musical expert can find something to appreciate and the man who only feels music without knowing it can find something to enjoy. (Bookfellow Citation1913, 242)

Anticipation and Echoes

Beyond hints of the musical middlebrow, the Sousa Band’s tour provided further foreshadowing and sustained resonance in Australasian musical practice. Most immediately, Sousa’s departure from New Zealand in August left one key antipodean adherent in his wake. As explained by Donald Westlake (Citation1999, 204), Launceston-based bandleader and composer Alexander Lithgow (1870–1929) became known as the Sousa of the Antipodes after his ‘Invercargill’ march of 1908, which had earlier broken phonograph sales records (Firth and Glover Citation2006 [1986]), was one of three marches played by local bands for the Sousa Band on the march to the Town Hall on their Melbourne arrival (Argus Citation1911a, 4). Skilled on cornet and violin, Lithgow shared something of Sousa’s industriousness in his role as a leading member of Tasmanian musical life: he was central to the influential St. Joseph’s Band, and composed more than 200 marches, of which many were published locally through his Commonwealth Band Music Publications company (Bourke Citation2017, 51). Lithgow’s Australasian context militated against his similarity to Sousa instrumentally, with many of his compositions scored for all-brass ensembles; select others, such as the Queen O’Dreams Waltz Intermezzo and Aboriginal Concert March, called for a ‘brass band (including reeds),’ which was more typical of the time and included clarinet, piccolo, and flute, but not saxophone (Lithgow ca. Citation1890–1930; Citation1910). The Sousa Band had performed in Launceston on two separate occasions, with the first billed as ‘The Event of the Age’ (Examiner Citation1911, 1), and Lithgow and Sousa may have met, although this is unclear (Bourke Citation2017, 48). The Sousa of the Antipodes and his music remain of contemporary relevance: ‘Invercargill’ is still a cornerstone of Australian service band repertoire, and in April 2019 a bronze statue of Lithgow was unveiled in the New Zealand town of the same name (Invercargill City Council Citation2019).

The advent of the Great War in 1914 forestalled the ascendency of mixed or military band models, at least as far as deployed ensembles were concerned. All-brass Australian bands proved advantageous in overseas settings, where ‘heat, cold, water, and dust-resistant all-metal instruments’ served as a ‘reassuring sonic symbol of Australian courage and determination to win this contest of unparalleled fierceness’ (Whiteoak Citation2002, 44).Footnote25 On the home front, the military band model remained an alternative to all-brass band practice, with exponents including the New South Wales Police Band, the Albury Town Band, and the New South Wales State Military Band, the latter welcoming saxophonist Jim Tougher as its bandmaster in April 1918 (Daily Telegraph Citation1918, 13). These shifting mores, perhaps ciphers for competing British and American influence as per ragtime, are one window into prevailing models and approaches to local musical practice over this time.

In the conflict’s aftermath, Australian brass bands continued debating the merits of adopting Sousa-like instrumentation. In one 1920 band journal editorial, an appeal was made to its readership to consider the benefits of mixed ensembles over all-brass instrumentation, commenting that the ‘brass band … [displays] a tendency towards monotony after a few items,’ while the ‘military band is full of colour and tone variety, almost like an orchestra’ (Australasian Bandsman Citation1920, 1). Like Sousa’s observations in 1913, the complexity of colours, and by extension flavours, that reeds offered brass bands was again evoked in culinary terms:

Where is the man who is brave enough to prefer a garden of all roses to one in which the choice blooms of nature are displayed in all their beauty. Where is the man who is prepared to advocate the toothsome flavour of an all roast meat dinner to the meal that includes the roast meat as well as the dainties that tickle the palate in a menu that covers all from the soup to the sweets and ices at the end, to say nothing of the smokes and the strong coffee as addenda? … There is no purely brass band—however perfect—that can compare with an equally perfect combination that is known as a military band. (Australasian Bandsman Citation1920, 1)

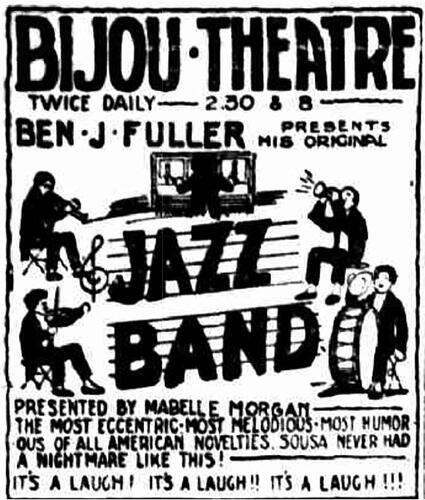

Instead, rhythms and melodies from the anonymous stream of local musical practice dictated terms, as the Australian Jazz Age developed through a ragtime-to-jazz transition period (ca. 1918–1923), and subsequently through the arrival of US and British dance bands (1923–1928). This first phase was proudly iconoclastic, and Fuller’s Jazz Band, the 1918 vaudeville act considered to have commenced the Australian Jazz Age, advertised its Melbourne concerts in opposition to Sousa’s respectability, promoting: ‘The most eccentric, most melodious, most humorous of all American novelties. Sousa never had a nightmare like this!’ (see ). By the mid-1920s, some 1600 ‘jazz bands’ were estimated as working in Australia,Footnote27 and the slowly rising influence of reed instruments in bands helped drive the introduction of a jazz category at Ballarat’s South Street championships in 1926 (Brisbane Citation1991, 180). By 1927, saxophones were photographed among the ranks of Launceston’s St. Joseph’s Band, once an all-brass ensemble led by Lithgow (Australasian Band and Orchestra News Citation1927, 1).

Figure 9. Advertisement for Fuller’s Jazz Band. Herald (Melbourne), 25 July 1918, 8. National Library of Australia. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article242736819. Reproduced with permission of the National Library of Australia.

As the 1920s progressed, Australian vaudeville stages continued to bear witness to the Sousa Band’s ongoing cultural influence. The 1924–1925 Australian tour of Canadian saxophone sextet The Six Brown Brothers included a parody of Sousa’s conducting style, where troupe leader Tom Brown instructed the group musically by means of ‘queer movements of his hands and feet, tugging at his tie, and counting the buttons on his coat,’ while the other members of the group ‘worked straight in military uniform,’ and ‘[closed] with a ripping sound from the whole band’ (Vermazen Citation2004, 123, 60, 188). A figure who once evoked awe and reverence now drew laughter. For Australian audiences whose affinity for militarism had subsided following the Great War, such a caricature captured the Zeitgeist, and aligned with an extant undercurrent of oppositional Australian sensibility. Brown’s lampooning of Sousa earned specific comment in reviews: ‘The leader, a master of facial inexpression, raised many hearty laughs and incidentally showed his complete control of the band by his ludicrous methods of conducting’ (Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate Citation1925, 6).

Meanwhile, Sousa’s legacies continued to be felt in the more respectable halls of popular music, through the leaders of dance-palais jazz bands. In 1932, the Australasian Band and Orchestra News tribute to Sousa included a reflection that his ‘marches took a sturdy hold of everybody down to the innumerable small boys who whistled them in the streets’ (Australasian Band and Orchestra News Citation1932, 3), and by this time, two ‘small boys’ from those audiences towered over the Australian dance band scene, both crediting Sousa’s Australian performances with igniting their musical pursuits. Band leader Jim Davidson (1902–1982) described the 1911 concerts as having sparked his interest in music, referring specifically in his memoir to Sousa’s ragtime-infused encores:

For the first time, I heard what a truly grand sound a fine band can make. … Sousa’s band concerts introduced the new beat to Australia, and provided a kind of subconscious apprenticeship into the sound of music I was to espouse for sixty-one years. (Davidson Citation1983, 18)Footnote28

In the military band realm, a similar adaptability was demonstrated from 1930 in the form of the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Company) Military Band, conducted by brass band leader Harry Shugg (de Korte Citation2018). In 1933 this ensemble was re-formed, and soon followed in the Sousa Band’s footsteps by conducting a national tour. Captain H.E. Adkins, imported from London’s Royal Military School of Music, Kneller Hall, led these performances and was described in the local press as ‘the world’s greatest authority on woodwind instruments’ (Evening News Citation1934, 9). Echoes from the Sousa Band’s 1911 tour rang further than the Sousa marches featured by this ensemble: in a moment of thought leadership of his own, Adkins ‘emphasized the need for [local] bandmasters to develop ambidexterity’ in their future programming (Sydney Morning Herald Citation1934, 6). The Australian Musical News even devoted two pages to Adkins’s tour, with editor Thorold Waters imploring his readers to ‘never belittle musical expansion, whatever the form it may take’ (Australian Musical News Citation1934, 1).

Far beyond the prosaic or ‘lowbrow,’ the Sousa Band presented a wealth of prescient musical offerings to its 1911 antipodean audiences. With instrumentation intimating notions of cultural diplomacy beyond the bandstand, and programmes conveying a spirit of cultural uplift, the ensemble rendered a range of sounds new to many Australian ears. Moreover, the secure hold of these performances in local cultural memory was reflected through light-hearted oppositional fun on the popular stage, and embodied in the prolific careers of the genre-spanning musicians the tour inspired. On such counts, the Sousa Band’s 1911 Australasian tour is deserving of overdue critical recognition as a vital inflection point in local twentieth-century musical practice.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Anthea Skinner’s (Citation2021) article in this journal, ‘Women in World War II RAAF Bands: An Untold Story,’ is an exception whose title aligns with this general contention. Roland Bannister (Citation1997, 164) described the space occupied by official military bands in musicological scholarship as an ‘enigmatic niche,’ owing to its ‘ideologically unpalatable’ ties to militarism, and, in international contexts, authoritarianism.

2 ‘Approved’ musical activities provided participants with a social or cultural dividend, and were seen to reinforce social cohesion; ‘anonymous’ activities generally held less socio-cultural status, all of which were ‘associated with playing for money’ (Whiteoak Citation1999, xvi–xvii).

3 Through an examination of the performance contexts and cultural dynamics of the saxophone in Australia (1853–1938), my PhD thesis critically examines the prevailing ‘lowbrow’ stereotype that the saxophone and banding movement have historically shared (Chapman Citation2023).

4 An earlier visit of Johannes Wildner’s Austrian Strauss Band was perhaps the high water-mark of the influence of German (and German-adjacent) bands in colonial Australia. A ‘huge military band plus a full orchestral string section and harp,’ it performed at Melbourne’s 1880 International Exhibition (Earl Citation2003, 92).

5 Whiteoak also credits the rise of the all-brass band to the accessibility and interchangeability of three-valve fingering patterns ‘ideal for work-damaged fingers,’ which the more complicated clarinet could not match. ‘It was noted that mediocre brass players might sound tolerable in a band, and often improve rapidly, but a mediocre clarinettist was “excruciating”’ (Whiteoak Citation2002, 43).

6 Mark Pinner details the local, largely all-brass bands that performed around this occasion (Pinner Citation2021, 178–90).

7 Sousa’s conducting style was remembered as ‘very interesting … quiet at first, but using gesticulation freely as the music went on, swaying to the rhythm, and describing all sorts of picturesque evolutions with hands and arms. All this display was governed by his personality, the real secret of Sousa’s success.’ The band’s movements also earned mention, such as during performances of The Stars and Stripes: ‘as the ensemble grew, various sections of the band walked out to the front of the platform and blared out their full tones in enunciating the theme. The sight of the line of trombone players, for instance, vigorously working the slides as their instruments took up the motive of the march in fortissimo volume, invariably roused the people to a high pitch of enthusiasm’ (Sydney Morning Herald Citation1932b, 8).

8 From the perspective of the saxophone, the French influence on the Sousa Band can be traced to the 1872 visit of the French Garde Républicaine band to Boston for the World’s Peace Jubilee and International Musical Festival, which informed the instrumentation of Gilmore’s band. As early as 1859, however, Gilmore had pioneered the incorporation of woodwinds into his ensemble at scale (Proksch Citation2021, 27).

9 Size played a role: in an 1889 article on band competitions, Sousa prescribed ‘first class’ bands as containing fifty musicians with saxophones, whereas ‘second class’ bands with thirty musicians went without (Proksch Citation2016, 10).

10 Whiteoak (Citation2002, 45–48) examines gender in the context of traditionally male-dominated Australian banding.

11 The 1871 introduction of a steamship service from San Francisco increased US cultural influence in Australia, and encouraged comparisons between the two: ‘[US] Americans believed they had achieved their great destiny, creating a Constitution, providing republican democracy, establishing economic prosperity, and the conquering of a continent, because they practised order, industry, cleanliness, punctuality and frugality, and they preached the virtue with almost messianic zeal.’ (Whiteoak Citation199943) Minstrelsy, for example, offered white Americans, and by extension white Australians, a ‘negative model for emulation’ (Waterhouse Citation1990, 110). Andrew Bisset also describes the fin-de-siècle emergence of an Australian identity ‘shaped by origins, land, and climate [that] combined to produce a new social order and a racially distinct type, different especially from the English’ (Bisset Citation1979, 41).

12 ‘The defeat of [Great Britain’s] navy would mean the loss of her colonies and be her eternal degradation’ (Darling Downs Gazette Citation1911, 4).

13 New Zealand’s political independence had been more recently achieved than Australia’s, through the proclamation of its dominion status in September 1907.

14 Bisset’s account was drawn from interviews with Australian musicians of the 1920s and 1930s, suggesting that Sousa’s visit grew in esteem, and perceived size, in later years.

15 Bierley (Citation2006, 288–90) details a selection of Sousa’s performed Australasian programmes, including their encores, which indicate that Sousa’s Yankee Shuffle—with its zestful tempo, and notable glissandi in the trombone melody—was one ragtime-tinged encore item. Reviews also recounted the two percussionists’ work on the ‘effects’ or ‘traps,’ in which the ‘shuffle of feet’ and the ‘clatter of wooden shoes’ were reproduced in Sousa’s ‘lively’ works (Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser Citation1911, 9).

16 Explicit ties to minstrelsy, such as the use of ‘vernacular’ English and references to ‘ol’-fashioned’ banjos, mark the eight-line poem accompanying the third movement’s appearance in the programme.

17 After the 1900 performances in France, Proksch notes that ‘it took less than a year for Sousa to go from the darling of Paris to an outspoken critic who was tired of pandering to his audience’s whims’ (Citation2020, 34). In 1903, Sousa wrote: ‘Ragtime is an established feature of [US] American music; it will never die, any more than Faust and the great operas will die’ (‘American Music and Ragtime’ Citation1903, 8).

18 Incidentally, Whiteoak cites the Sousa Band’s 1912 recording of ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ as emblematic of a new, swung, ‘ragtime rhythmic treatment’ (Whiteoak Citation1999, 119).

19 The same review charmingly notes that ‘the audience wanted the band back an unlimited and altogether unreasonable number of times’ (Sun Citation1911a, 5).

20 Ben Vereecken, Albert A. Knecht, and Stanley Lawton were the Sousa Band’s three saxophonists for the world tour (Bierley Citation2006, 90).

21 Bizet’s incidental music accompanied the original staging of the play in 1872, which was unsuccessful. Remarkably, interest in Bizet’s score led to the play’s reintroduction (Macdonald Citation2014, 345).

22 Proksch notes that this essay ‘shows Sousa preparing for direct comparison to European bands for the first time in his career’ (Citation2016, 25).

23 Popularity did not necessarily equate to profitability: manager Edward Branscombe, who oversaw the Sousa Band’s tour, was ‘not so happy at the end’ after the ensemble had travelled around Australia via ship and train ‘in first-class style’ (Australasian Band and Orchestra News Citation1932, 3).

24 Beyond class-based distinctions, ongoing antipathy between Australia’s amateur banding movement and the professional musicians whose work they occasionally undercut may also help to explain this divide (Blythell Citation1997, 69). Sousa, for his part, may not have minded: in 1912, he wrote dismissively about ‘blue-nosed “highbrows” who, after a residence of many years in European countries, have come back to [the US] with a kind of snobbish all-knowing superiority which is, to say the least, aggravating’ (Proksch Citation2016, 108).

25 In this regard, US–Australian timbral entente ebbed as the United States remained neutral in the Great War until 1917: the notion ‘that we were all transplanted Britons … was undermined by the Great War. How could they claim there was a unity of blood in the Anglo-Saxon world when the United States delayed so long before entering the conflict, and refused to join the League of Nations? Thousands of Australian troops saw for themselves that they were different from the English, and the Anzac became the expression of national identity’ (Bisset Citation1979, 41–42).

26 Sousa continued to advocate for the saxophone over this time. A 1925 article from New York, headlined ‘Sousa Dignifies the Saxophone,’ saw Sousa mount a three-point defence of the instrument: he quoted characterizations of the instrument from Berlioz’s orchestration treatise, criticized the Metropolitan Opera for replacing saxophones with clarinets in a performance of Massenet’s Le roi de Lahore, and spoke to his own work—which by this time included a saxophone ensemble titled Sousa’s Syncopators—asserting: ‘We are doing nothing revolutionary. We merely are moving the saxophones down front so the audience may see what a fine family of instruments they can be—when they keep good company’ (Proksch Citation2020, 44).

27 At this time, Australian ‘jazz bands’ refers to dance bands, but with instruments such as saxophones taking the place of strings, flutes, and clarinets. Of these developments, Bruce Johnson notes: ‘[Jazz] represented modernity, and one of the distinguishing aspects of modernity was the rising level of constructed sound’ (Citation2019, 51).

28 Davidson continued: ‘During my later years I realised that Sousa’s men played with an embouchure technique with little or no vibrato, which produces a clear clarion tone. … My parents delighted in Sousa’s orchestration of the New Orleans crib house tune “Ta-Ra-Ra-Boom-De-Ay”’ (Citation1983, 18).

29 A double reed feature mentioned in the Sousa Band’s Melbourne reviews is Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly, in which ‘the oboes [give] the question, answered by the trombones and other instruments, and the bassoon putting in some comments of his own on the matter’ (Leader Citation1911, 35).

30 Concordant with Sousa’s musical approach, Pettifer is described by Whiteoak as one of the ‘great stylists of the 1930s … whose professional roots went back to a time before “orchestral” musicians began to define themselves as either “legit,” “semi-legit” (e.g. popular theatre musicians), or dance stylists’ (Whiteoak Citation1999, 242).

References

- Age (Melbourne). 1877. ‘Italian Opera.’ 20 August 1877, 2.

- ‘American Music and Ragtime.’ 1903. Music Trade Review (New York) 37, no. 14: 8.

- Argus (Melbourne). 1907. ‘Besses o’ th’ Barn Band. Welcome to Melbourne.’ 29 July 1907, 7.

- Argus (Melbourne). 1911a. ‘Welcoming Sousa.’ 26 May 1911, 4.

- Argus (Melbourne). 1911b. ‘Sousa in Melbourne. Bandsmen’s Greeting.’ 6 June 1911, 7.

- Argus (Melbourne). 1911c. ‘Farewell Concert.’ 10 July 1911, 9.

- Australasian (Melbourne). 1889. ‘Music: Mr. Cowen’s Exhibition Performances.’ 16 February 1889, 51.

- Australasian Band and Orchestra News (Melbourne). 1927. ‘St. Joseph’s Band. Launceston, Tasmania.’ 26 April 1927, 1.

- Australasian Band and Orchestra News (Melbourne). 1932. ‘Sousa’s Example for Our Bandmasters.’ 26 March 1932, 1–3.

- Australasian Band and Orchestra News (Melbourne). 1933. ‘The Coming of the Military Band.’ 26 December 1933, 2.

- Australasian Bandsman (Bathurst). 1920. ‘Color in Music.’ 26 May 1920, 1.

- Australian Musical News. 1911. ‘A Foreword.’ 1, no. 1 (July 1911): 1.

- Ballarat Star. 1911. ‘Sousa’s Band.’ 8 July 1911, 8.

- Bannister, Roland. 1997. ‘Meaning in Military Music: An Australian Case Study.’ Australasian Music Research 2–3: 161–74.

- Bierley, Paul E. 1984. The Works of John Philip Sousa. Columbus, OH: Integrity.

- Bierley, Paul E. 2006. The Incredible Band of John Philip Sousa. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Bisset, Andrew. 1979. Black Roots White Flowers. Gladesville: Golden Press.

- Blythell, Duncan. 1997. ‘Brass Bands.’ In Oxford Companion to Australian Music, edited by Warren Bebbington, 68–70. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Bookfellow: The Australasian Review and Journal of the Australasian Book Trade (Sydney). 1913. ‘The Modern Band.’ 15 October 1913, 240–42.

- Bourke, Chris. 2017. Good-bye Maoriland: The Songs and Sounds of New Zealand’s Great War. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Brisbane, Katherine, ed. 1991. Entertaining Australia: An Illustrated History. Sydney: Currency Press.

- Chapman, Ross. 2023. ‘Liminaire: Performance Contexts and Cultural Dynamics of the Saxophone in Australia, 1853–1938.’ PhD diss., University of Melbourne.

- Chowrimootoo, Christopher, Kate Guthrie, John Howland, Andrew Flory, Chris McDonald, Heather Wiebe, and Richard Taruskin. 2020. ‘Colloquy: Musicology and the Middlebrow.’ Journal of the American Musicological Society 73, no. 2: 327–95. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.2020.73.2.327

- Clarence and Richmond Examiner (Grafton). 1911. ‘Sousa’s Band.’ 16 May 1911, 5.

- Daily Telegraph (Sydney). 1911a. ‘Music. The Coming of Sousa’s Band.’ 6 May 1911, 6.

- Daily Telegraph (Sydney). 1911b. ‘Sousa’s Band.’ 31 May 1911, 10.

- Daily Telegraph (Sydney). 1918. ‘State Military Band: The New Conductor.’ 29 April 1918, 13.

- Danner, Phyllis. 1998. ‘John Philip Sousa: The Illinois Collection.’ Notes 55, no. 1: 9–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/900344

- Darling Downs Gazette (Queensland). 1911. ‘Kaiser’s Ambition.’ 30 August 1911, 4.

- Davidson, Jim. 1983. A Showman’s Story: The Memoirs of Jim Davidson. Adelaide: Rigby.

- de Korte, Jeremy. 2018. ‘The ABC Military Band: An Ensemble of the Times.’ Band Blasts from the Past. bandblastsfromthepast.blog/2018/07/12/the-a-b-c-military-band-an-ensemble-of-the-times

- Earl, Chris. 2003. ‘Brass Bands.’ In The Currency Companion to Music and Dance in Australia, edited by John Whiteoak and Aline Scott-Maxwell, 90–96. Sydney: Currency House.

- Evening News (Rockhampton). 1934. ‘ABC National Military Band.’ 16 January 1934, 9.

- Examiner (Launceston). 1911. Advertisement for ‘The Incomparable Sousa the March King.’ 12 May 1911, 1.

- Firth, J.F., and Margaret Glover. 2006 (1986). ‘Lithgow, Alexander Frame (1870–1929).’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, [Canberra]: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lithgow-alexander-frame-7206/text12469

- Harvey, Paul. 1995. Saxophone. London: Kahn and Averill.

- Invercargill City Council. 2019. ‘Composer Alex Lithgow’s Statue Unveiled.’ https://icc.govt.nz/composer-alex-lithgows-statue-unveiled

- Johnson, Bruce. 2019. Jazz Diaspora: Music and Globalisation. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351266680

- Keightley, Keir. 2022. ‘Canned Music, Canned Culture: John Philip Sousa and the Proto-Middlebrow.’ In The Oxford Handbook of Music and the Middlebrow, edited by Kate Guthrie, and Christopher Chowrimootoo, Online ed., 1–24. New York: Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197523933.013.1

- Leader (Melbourne). 1911. ‘The Sousa Band.’ 10 June 1911, 35.

- Lithgow, Alex F. ca. 1890–1930. Aboriginal Concert March. Launceston: Commonwealth Band Music Publications.

- Lithgow, Alex F. 1910. Queen O’Dreams Waltz Intermezzo. Launceston: Commonwealth Band Music Publications; W.H. Paling & Co.

- Macdonald, Hugh. 2014. ‘Review of L’Arlésienne: Drame en trois actes et cinq tableaux. Version originale de 1872 pour ensemble instrumental et chœur, by Georges Bizet.’ Notes 71, no. 2: 345–49. https://doi.org/10.1353/not.2014.0130

- Murphy, Kerry. 2014. ‘Thomas Quinlan and the “All Red” Ring: Australia, 1913.’ Context 39: 79–88.

- Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate. 1925. ‘Betts’ Theatre Royal.’ 2 March 1925, 6.

- Newsletter: An Australian Paper for Australian People (Sydney). 1910. ‘Theatrical Gossip.’ 30 July 1910, 2.

- Pinner, Mark. 2021. Brass Bands in Colonial New South Wales: A Social History. Healesville: Fernmill.

- Proksch, Bryan. 2016. A Sousa Reader. Chicago: GIA Publications.

- Proksch, Bryan. 2020. ‘Sousa’s Vacillating Views on Ragtime and Jazz.’ Journal of Band Research 55, no. 2: 29–53.

- Proksch, Bryan. 2021. The Golden Age of American Bands. Chicago: GIA Publications.

- Punch (London). 1925. ‘Charivaria.’ 23 December 1925, 673.

- Queensland Figaro. 1911. ‘Theatrical Notes.’ 20 April 1911, 16.

- Referee (Sydney). 1911. ‘Theatrical Gazette: Talk with Sousa.’ 7 June 1911, 15.

- Richmond River Express and Casino Kyogle Advertiser (Casino, NSW). 1911. ‘Sousa’s Band.’ 2 June 1911, 9.

- Semmens, Judy. 1986. ‘My Father the Musician (The Early Years).’ Unpublished typescript.

- Skinner, Anthea. 2021. ‘Women in World War II RAAF Bands: An Untold Story.’ Musicology Australia 43, no. 1-2: 22–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/08145857.2021.2000849

- Sousa, John Philip. 1900. ‘The Ideal Band.’ Independent (New York), 25 January 1900, 231–33.

- Sousa, John Philip. 1906. ‘The Menace of Mechanical Music.’ Appleton’s Magazine (New York) 8, no. 3: 278–84.

- Sousa, John Philip. 2018. ‘The Federal March (1910).’ In The Complete Marches of John Philip Sousa, edited by Jason K. Fettig and Donald Patterson, Vol. 4, no. 68. Marine Band Library. Washington, DC: United States Marine Band.

- Sun (Sydney). 1911a. ‘Sousa’s Sixty.’ 11 July 1911, 5.

- Sun (Sydney). 1911b. ‘The Sousa Concerts.’ 12 July 1911, 1.

- Sydney Morning Herald. 1901. ‘Royal Marine Band Concert.’ 23 May 1901, 10.

- Sydney Morning Herald. 1932a. ‘Mr. J.P. Sousa: Death Announced.’ 7 March 1932, 9.

- Sydney Morning Herald. 1932b. ‘Music and Drama. The Success of Sousa.’ 12 March 1932, 8.

- Sydney Morning Herald. 1934. ‘ABC Military Band.’ 5 February 1934, 6.

- Tregear, Peter. 2014. ‘Post-Colonial Tristesse: Aspects of Wagner Down Under.’ Context 39: 69–77.

- Vermazen, Bruce. 2004. That Moaning Saxophone: The Six Brown Brothers and the Dawning of a Musical Craze. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Warfield, Patrick. 2009. ‘John Philip Sousa and “The Menace of Mechanical Music”.’ Journal of the Society for American Music 3, no. 4: 431–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752196309990678

- Waterhouse, Richard. 1990. From Minstrel Show to Vaudeville: The Australian Popular Stage, 1788–1914. Sydney: New South Wales University Press.

- Waterhouse, Richard. 1995. Private Pleasures, Public Leisure: A History of Australian Popular Culture since 1788. South Melbourne: Longman Australia.

- Waters, Thorold. 1934. ‘Musical Expansion in Every Form: Give an Ear to the Military Band.’ Australian Musical News 24, no. 6 (January 1934): 1–2.

- Westlake, Donald. 1999. From Me to You: The Life & Times of Clive Amadio. Terrey Hills, NSW: Bowerbird Press.

- Whiteoak, John. 1999. Playing Ad Lib: Improvisatory Music in Australia, 1836–1970. Sydney: Currency Press.

- Whiteoak, John. 2002. ‘Popular Music, Militarism, Women, and the Early “Brass Band” in Australia.’ Australasian Music Research 6: 27–48.

- Whiteoak, John. 2015. ‘Demons of Discord Down Under: “Jump Jim Crow” and “Australia’s First Jazz Band”.’ Jazz Research Journal 8, no. 1-2: 23–51. https://doi.org/10.1558/jazz.v8i1-2.26775

- Whiteoak, John. 2018. ‘What Were the So-Called “German Bands” of Pre-World War I Australian Street Life?’ Nineteenth-Century Music Review 15, no. 1: 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479409817000088

- Whiteoak, Ralph. 2003. ‘Saxophone.’ In The Currency Companion to Music and Dance in Australia, edited by John Whiteoak and Aline Scott-Maxwell, 597–98. Sydney: Currency House.