ABSTRACT

Clinical Relevance

Preschool vision screening is essential for the early detection and treatment of eye and vision problems.

Background

The rate of parental adherence to referrals for comprehensive examination was assessed and factors and potential barriers associated with adherence were identified.

Methods

In a prospective cohort study design, parents were offered to bring their 3–6 year old aged children to free-of-charge vision screening tests at community-based Mother Child Health Centers. Children with abnormal findings were referred to an ophthalmologist examination. Parents were interviewed three to six months after the referral to evaluate adherence and barriers. Barriers were organised into a conceptual framework of parental predisposing and health system factors. Adherence and barriers were assessed by sex, age, ethnic group and socio-economic-status.

Results

Altogether 1283 children (mean age 4.5 ± 0.6 years, 47.8% girls) were screened in the Jerusalem district, Israel. The ethnic groups, Jewish (ultra-Orthodox 51.4%, secular/religious 33.2%) and Arab (15.4%), were similar by age and sex, but not by socio-economic status. The overall referral rate was 23.0% (N = 295). Referral rate was not associated with demographic factors. Overall, 54.3% (N = 160) of parents adhered to the referral to bring the child for a full eye examination. Adherence did not differ with sex, ethnicity or socio-economic-status. Parents of 5-6-year-old children were significantly more likely to adhere than parents of younger children. Of parents who did not adhere, 79.3% were attributed to predisposing factors, 16.3% to system factors and 4.4% to other reasons.

Conclusions

Only half the parents proceeded with the recommended full eye examination. Parents of older children were more likely to adhere to referral. In contrast with vaccinations provided by Mother Child Health Centers, adherence to vision screening did not vary based on ethnicity or socio-economic factors. Since most barriers were associated with predisposing factors of parents, interventions to improve adherence should include parental education.

Introduction

Good vision is a critical element for childhood development, education, employability and lifelong independence.Citation1 Blindness and mild to severe vision impairment are associated with a large economic burden worldwide.Citation2 Uncorrected refractive error is the leading cause of preventable vision impairment and the second leading cause of preventable blindness in the world, even in developed countries.Citation3 In preschool children in the United States, it has been estimated that the number one cause of vision impairment is uncorrected refractive error.Citation4

Preschool vision assessments and eye examinations are especially important for detection of refractive error, strabismus and amblyopia. If left untreated, significant refractive error and strabismus can lead to amblyopia and have a detrimental effect on visual developement,Citation5,Citation6 with intervention under the age of seven years having the highest efficacy.Citation7 Furthermore, significant uncorrected refractive error is associated with decreased visuo-cognitive ability, reading ability, and visual attention in young children.Citation8 In contrast, some refractive errors such as low astigmatism and hyperopia may be part of the children’s normal development.Citation9

The prevalence of refractive amblyopia risk factors ranges from 5.7% to 21.8% in 3–5-year old children (depending on the age category)Citation10 and the prevalence of strabismus from 1.0–4.6%.Citation11 According to a report from the Israel Knesset, approximately 5% of the preschool children have one of the following conditions: hyperopia, myopia, astigmatism, strabismus or in rare cases, cataract.Citation12 However, this report was most likely limited to refractive errors that lead to amblyopia, since the prevalence of refractive errors in this population is typically much higher.Citation10

There is a broad consensus that preschool vision screening is essential for the early detection and treatment amblyopia risk factors and significant refractive error.Citation13,Citation14 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), an independent panel of experts in evidence-based preventive medicine, has recommend screening all children aged 3 to 5 years at least once to detect amblyopia and its risk factors.Citation15

When performed effectively, vision screening can maximise the rate of problem detection and minimise the cost of referrals.Citation16 However, screening is only the first step; treatment depends on many other factors that lead to parents bringing children who fail screening for comprehensive eye examinations. Pizzi et al.Citation17 has divided these factors into three categories: (1) predisposing factors related to parents, including their awareness of the importance of screening and follow up with a comprehensive eye examination; (2) systematic factors that include availability and accessibility of comprehensive services; and (3) financial factors such as lack of health insurance and cost of treatment.

Parental adherence to preschool vision screening referrals has been studied previously in the USA,Citation17–21 IndiaCitation22 and GermanyCitation23 and report various rates of adherence. The different rates are likely due to the unique combination of socio-economic factors, immigration status and physical and economical access to health care at each location. Thus, it is important to assess this issue in a wider range of locations. Adherence has not been evaluated in preschool children in Israel, although compliance with childhood vaccination has been shown to vary by ethnicity and socio-economic status.Citation24,Citation25

Israel offers a good venue to assess adherence since all children of citizens are required by law to have health care insurance, thus financial factors will not be a barrier. Furthermore, in Israel, Mother Child Health Centers (MCHC) provide free paediatric preventative health services to all children (regardless of citizenship) from birth to six years of age, as mandated by law.Citation26 The majority (>96%) of parents chose to bring their children to services offered by the MCHC and these clinics have been recognised by the World Health Organization with a certificate of achievement “worthy of national recognition” for a “national community-based children’s health project that promotes ‘health for all’ values of equity, solidarity, participation, inter-sectoral approaches and partnership”.Citation27

This study aims to (1) evaluate the percent of children who failed vision screening whose parents adhered with the referral for a comprehensive eye examination; (2) assess adherence according to sex, ethnicity, age group and socio-economic status (SES) of the child; and (3) determine barriers to adherence for those parents who do not bring in children for comprehensive eye examination.

Methods

Study population

The study included children between the ages of 3–6 who attended 12 MCHC in the District of Jerusalem. Children who wore glasses or were under the care of an ophthalmologist were excluded from this study. In the district of Jerusalem, children are assigned to neighbourhood MCHC. Most neighbourhoods in this study are populated by one of two homogenous ethnic populations: ultra-Orthodox Jewish or Arab. The rest are heterogenous mixes of secular and religious Jews, who resemble one another in terms of educationCitation28,Citation29 and outlook towards modernity,Citation30 and thus were categorised together. Therefore, the study population was categorised into three ethnic populations based on the neighbourhood of the MCHC: ultra-Orthodox Jewish, Arab and religious/secular Jewish.

The socio-economic status (SES) of each participant was based on the socio-economic index of the neighbourhood where the children lived.Citation31 The Israel Central Bureau of Statistics created this index based on many factors such as income, crowding in housing, unemployment and economic stress, on a scale from 1–10, with 10 being the highest. Children living in areas indexed as 1–5 were categorised as low-to-medium socio-economic status and children living in 6 and above as high socio-economic status. This study was approved by the Helsinki committee of the Ministry of Health (# MOH-201-2017).

Vision screening procedure

Vision screening tests were carried out by optometry students under the supervision of a licenced optometrist (OSC). First year students measured distance visual acuity and performed a cover test, and fourth year students performed retinoscopy using a rack-lens bar. Dozens of optometry students participated in this study.

The vision screening procedures were as follows: monocular distance visual acuity; assessment with Lea Symbols with crowding bars at three metres; non-cycloplegic retinoscopy; and stereoacuity with a Randot test and cover test. Failure criteria was based on the American Association for Paediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus guidelinesCitation13 for at least one eye: visual acuity 6/12 or worse; retinoscopy results for sphere >-1.00 D or >+1.50D and/or cylinder >1.50 D; esophoria or heterotropia in the cover test; or stereopsis results lower than 100 seconds of arc. If a child failed one of the procedures, they were all repeated by the optometrist (OSC). Children who were unable to cooperate with VA or retinoscopy received a referral.

The screening procedures took approximately 20 minutes. All parents received a written summary of the screening results along with a short oral explanation. A copy of the results was saved in the MCHC file of the child. Children who failed the screening received a written referral to an ophthalmologist. This type of secondary care is provided free of charge by health care funds in the community. In addition, their parents received an oral explanation of the results from the optometrist who also explained the goals and importance of the referral to the ophthalmologist. Each child received a unique code, and the demographic data of the child along with the screening examinations results were recorded anonymously in google forms using this code.

In the process of continued care, MCHC staff contacted parents of children who failed the screening between 3 to 6 months after the referral date, to determine if the child had seen an ophthalmologist and if so, the results of the examination were recorded. If the parent did not comply with the referral to an ophthalmologist, then the importance of the full examination was explained to parents and a subsequent phone-call was made several months later. A standardised script was used for the interview (Appendix A). However, the interviewer was permitted to ask additional questions if he/she deemed it relevant. The results of the standard script and summary of additional questions were recorded along with the unique code of each child.

Two masked reviewers (AGS and HBE) reviewed the answers to the script and assigned barriers according to the following categories: (1) the parents did not have time to take the children in for a full examination; (2) the parents forgot about the referral; (3) the parent believes that the child does not have a problem, despite the referral; (4) the parent believes that the child is too young for a full eye examination; (5) the parent believes that the child will not cooperate with a full eye examination; (6) no appointment was available; (7) the parents did not have insurance; and (8) other reasons. Categories were condensed according to previous studiesCitation17: Categories 1–5 were grouped into predisposing factors and categories 6 and 7 into system factors. In cases where the reviewers disagreed, a third reviewer (DRZ) was asked to consider the case, which was discussed until consensus reached.

Sample size

Several outcomes measures were used to calculate sample size using WinPepi (11.63 software). For comparison of the failure rate between different ethnicities and sexes, a failure rate of 24% was used based on a previous study.Citation32 Assuming a precision of 0.06 and with a 95% confidence interval, a sample size of 195 was required for each sub-group. For comparison of adherence, a rate of 53% was used based on a previous study.Citation18 Assuming a precision of 0.07 and a 95% CI a sample size of 196 was required. Thus, this study was sufficiently powered.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used. Continuous variables such as referral rates were presented as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Children were divided into the following age categories: 3–4, >4–5 and >5–6 years of age. Categorical variables were analysed by Chi-squared test. Post-hoc analysis was done with Bonferroni correction. Comparisons of continuous variables between two groups was performed using unpaired sample t-test and between more than two groups using one-way ANOVA. A two-sided P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Results

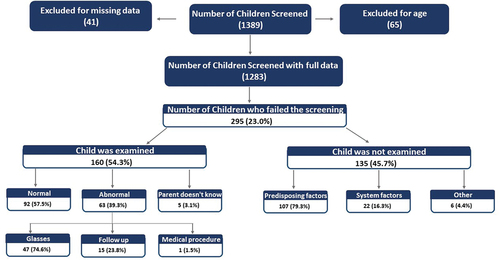

presents an overall description of the research study in which 1389 children were screened from Dec. 2017 to June 2019. Of these, 1283 met the inclusion criteria (65 did not meet the age criteria and 41 were excluded for missing data). Of these, 295 received a referral for a full examination and were contacted by MCHC staff. Of the parents contacted, 160 reported adhering with the referral for a full eye examination, while 135 did not adhere with the referral. The results of the eye examinations (as reported by the parents) and barriers for adherence are reported below.

Most of the children screened were ultra-Orthodox (51.4%, N = 660), while the rest were secular and religious (33.2%, N = 426) or Arab (15.4%, N = 197) (). The average age of the children was 4.5 ± 0.6 year (range 3.0–5.9 years). Most of the children in this study (87.6%) lived in areas at the lowest end of the socio-economic spectrum (levels 1–5) and were classified as low-to-medium SES (). The rest (12.4%) lived in areas at the higher end and classified as high SES (levels 6–10).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study participants.

The sex of the children was 47.8% female and 52.2% male (), which is not significantly different from the sex distribution in 0–4 year old children (according to ICBS 2017 census, in the age group there were 51.4% boys and 48.6% girls in Israel,Citation33 χ2(1) = 0.0047, p = 0.95).

There was no significant difference between the ethnicities in terms of age or sex. Since all Arab and ultra-Orthodox children lived in neighbourhoods with low-to-medium SES indices, this variable was analysed continuously using one-way ANOVA based on SES index. Ultra-Orthodox and Arab children were more likely to be from a low-to-medium SES (100%) than secular/religious (62.7%; p < 0.001, ()).

The overall referral rate was 23.0% (N = 295, 95% CI:20.1%-25.0%). As shown in , no significant differences were observed in the overall referral rate between girls and boys (22.0% vs. 23.9%) or by ethnicity (21.7%, 26.8% and 19.3%, for ultra-Orthodox, religious and secular, Arab, respectively). No difference in referral rate was observed between the different age groups of children or between low-to-medium and high SES.

Table 2. Referral rate by sex, ethnicity, age group and socio-economic status (SES).

Only 38 children received referrals for being unable to comply with the screening procedures (3.0% of all children screened and 12.9% of all children referred). Of these, most were boys (N = 28) and almost half were 3–4 years of age (N = 17). Boys were more likely to be referred for non-compliance than girls (4.2% vs. 1.6%, χ2(1) = 7.23, p = 0.007). Post-hoc analysis showed that 3–4 year old children were more likely to be referred for non- compliance than 5–6 year old children (5.8% vs. 0.6%, χ2 (2) = 14.52, p = 0.001). After post-hoc analysis, no difference was observed in the referral rate as a function of ethnicity.

Children who complied with the procedures could be referred for abnormal results in one or more of the screening procedures (i.e visual acuity, retinoscopy and cover test). Indeed, most children (66.8%, N = 197) were referred for failure of more than one procedure and the rest (33.2%, N = 98) just failed one procedure. The reasons for referral included abnormal retinoscopy (9.7%, N = 124), abnormal visual acuity (6.6%, N = 85) and abnormal cover test (5.8%, N = 74). There was no difference in failure rates as a function of sex or ethnicity. However, post-hoc analysis showed that 5-6-year-old children were more likely than 3-4-year-old children to need a referral due to abnormal results of cover test (8.3% vs. 3.5%, χ2 (2) = 6.69, p = 0.035).

For the children who received a referral, 54.3% (N = 160) of parents reported that their child had received a comprehensive eye examination ( and ). No difference in adherence was observed between parents of girls and boys (53.3% vs. 55.0%) or between different ethnicities (59.4%, 47.3%, and 55.2%, for ultra-Orthodox, religious and secular and Arab, respectively) or between different SES (55.4% vs. 42.8%, low-to-medium and high, respectively). Post-hoc analysis showed that parents of 5-6-year-old children were significantly more than likely to comply with the full examination than parents of younger children (50.0%, 49.3% and 69.5%, for 3–4, 4–5 and 5-6-year-old children, respectively, p = 0.01).

Table 3. Adherence to referral for comprehensive vision examination by sex, ethnicity, age and socio-economic status (SES).

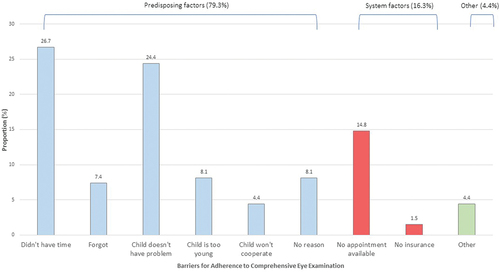

Parents of 45.7% (N = 135) did not adhere with the referral for a full eye examination, reporting various barriers (). Predisposing factors (79.3%, N = 107) included parents not having time (26.7%, N = 36), parents did not think the child has a vision problem (24.4%, N = 33), parents forgot (7.4%, N = 10), parents thought the child was too young for a complete examination (8.1%, N = 11), parents thought the child would not cooperate with a complete examination (4.4%, N = 6), and parents not having a reason for not adhering (8.1%, N = 11). System factors (16.3%, N = 22) included an appointment not being available (14.8%, N = 20) and parents not having insurance (1.5%, N = 2).

Six (4.4%) parents had other reasons that did not fall into any category for not adhering to the referral. Of these, two parents were not able to communicate with the interviewer due to language, one child was already under the care of an ophthalmologist and the reason was not recorded for three children. No differences were observed in adherence as a function of ethnicity, age, or SES (). However, the barriers were distributed differently for boys and girls (p = 0.03). It was not possible to determine in which barrier category the difference lie, due to the small sample size.

Table 4. Barriers to adherence by sex, ethnic and age group and socio-economic status (SES).

For children who had an eye examination, 57.5% of parents reported normal findings, while 39.3% had abnormal findings and the rest did not know the results (). For the children with abnormal findings, 74.6% were prescribed spectacles, 23.8% were asked to return for follow up and one had a medical intervention due to amblyopia (the parent could not recall the name of the intervention).

The average time to a full examination was 1.2 ± 1.9 months (range: 1 day to 10 months). No difference in time between referral and appointment was observed for sex, ethnicity, age category or SES (Appendix B).

Discussion

Preschool vision screening can identify children at risk for amblyogenic risk factors. However, for screening to have an impact on public health, parents must adhere to referral recommendations. In the study population, only 54% of parents reported bringing their children to a full eye examination, mostly due to predisposing factors that pointed to a lack of awareness on the part of the parent regarding the importance of full eye examination. These findings suggest that interventions to increase adherence should focus on parental education. This notion is supported by a recent qualitative study in NigeriaCitation34 that identified the belief of the parent that their child does not have an eye problem (despite the referral) and beliefs about eyeglasses as modifiable barriers. The parents in this study recommended educating the public about the important of child eye care.

Few previous studies have addressed the issue of parental adherence to vision screening referrals and the reported adherence rates range between 25% in the USACitation21 to 83% in Germany.Citation23 The different rates may be a function of interventions to increase adherence, socio-economic status, education or accessibility of services.

In the current study, parents were called by Mother Child Health Care staff after receiving the referral. The parents who had not yet complied were given information regarding the importance of the full examination and encouraged to schedule an appointment. Thus, the 54% adherence found in this study is best compared to previous studies in which interventions were implemented to increase adherence. An adherence rate of 25% reported in K-5th grade children in the USA, was after a social worker called parents up to three times to get consent for the full examination.Citation21 Pizzi et al.Citation17 found that an intervention program aimed at parents of school age children who failed vision screening increased adherence from <5% to 59.2%. This intervention program involved a social worker contacting parents to identify and resolve barriers and help them schedule an appointment. A similar intervention increased adherence of parents of school age children to 52%.Citation35 Meharavan et al.Citation20 found that educating parents of preschool children during the vision screening examination using pamphlets and videos increased the adherence rate from 65.1% to 75.3%.

The children in this study resided in areas of various socio-economic statusCitation31 and ethnicities. Most of the children (87.6%) were from areas that have a low-to-medium socio-economic status. In addition, some children (15%) belonged to the Arab minority and were from neighbourhoods with low socio-economic status. Indeed, similar to the entire population, ultra-Orthodox and Arab, children were significantly more likely to be from a low-to-medium SES.Citation31 Despite these differences, adherence was not a function of ethnicity. This is in contrast to a previous study in Germany where kindergarten children from migrant groups were less likely to adhere with vision referrals than the general population (47.3% vs 83.5%, respectively).Citation23

The results for adherence with referrals for vision screening are very different from compliance with vaccination, where large differences are seen as a function of ethnicity and SES. For example, coverage for polio vaccination was higher in the Arab population (92.4%) than the Jewish population (59.2%) for all SES clusters, but was inversely proportional to SES in the Jewish population.Citation24 In the Jerusalem District, ultra-Orthodox children have a lower rate of routine vaccination than all other communities (78.4% vs. 90.1%).Citation25 The decreased gap between ethnicities in adherence to vision examination referrals might reflect the importance of early reading to the ultra-Orthodox community. In addition, it might be due to a general lack of knowledge regarding the importance of vision testing across all populations. Supporting this notion, the overall vaccination rate at MCHC is much higher than the adherence with vision screening referrals. This suggests that parental education programs need to be targeted to all parents, regardless of ethnicity or SES.

Age was found to be associated with adherence to referrals; parents of 5-6-year-old children were more likely to take them for a full examination than parents of younger children. This may be due to parents being aware of the importance of vision in the first grade. It shows that if parents think that the full examinations are important, they will be more likely to adhere with the recommendations. The parents of younger kids come from the same neighbourhood and socioeconomic background as parents of older kids, supporting the notion that parents believe that before first grade, vision should be monitored, as it may affect their educational achievements.

To design interventions to increase adherence to vision screening referrals it is important to identify the barriers. These barriers may differ according to culture and access to health care. Pizzi et al.Citation17 suggested a conceptual framework for categorising barriers: predisposing factors, system factors and financial factors. Since Israel has universal health insurance, financial factors should not prevent parents from adherence. Almost all parents (79%) reported predisposing factors as the barrier for lack of adherence. In contrast, only 15% reported that appointment with an ophthalmologist was not available. Similarly, predisposing factors were barriers for 90% of parents in a previous study in the USA.Citation17

In contrast, in developing countries system factors may be the main barrier. In India, with a adherence rate of only 35%, the main barrier was financial with the most influential barriers being costs of transportation, fees of the hospital and doctors, and taking time off of work.Citation22 In addition, in a recent qualitative study in Nigeria, parental belief regarding cost and household situation emerged as themes that were barriers to adhering to follow up eye examinations.Citation34

In the current study, two parents reported that they did not adhere to the referral since they did not have health insurance. The MCHC services are free to all children regardless of citizenship. While all Israeli children are mandated by law to have health insurance, it is optional for foreigners. Thus, these parents may have been non-citizens. However, there are costs other than the full eye examination, such as transportation to the clinic, time away from work and the cost of the spectacles, if needed. The interviewer did not ask a specific question regarding costs and the parents would have been unlikely to bring up financial difficulties to an unknown interviewer.

The barriers did not differ by ethnicity or age, although there was a difference by sex. Previous studies of parental barriers to adherence with full eye examinations either did not find a difference by sexCitation17,Citation21,Citation23 or did not analyse according to sex.Citation19,Citation22 The reason for the finding in this study is not clear, but may reflect the small sample size in each sub-category.

The low rate of adherence may reflect a lack of continuity of care, since primary care for children in Israel is divided into curative services provided by one of four health funds and preventative services provided by MCHC. There are many advantaged to this system but also disadvantage, which may have impacted parental adherence. If both curative and preventative care were under one roof, then medical information would be in one electronic medical record.Citation27 Instead of preventative MCHC staff referring the child to the health fund for further evaluation, the health fund would facilitate continuity of care and smooth access to diagnosis and treatment. If the same paediatrician sees the child both in sickness and in health, then he or she will develop a rapport with parents and encourage them to adhere to recommendation for continuity of care.Citation27 This might have reduced some of the predisposing barriers to adherence observed in this study. In support of this notion, the coverage rate for vaccinations, which are given at MCHC and do not require referral to the health fund, is much higher than adherence with referrals to vision screening.

As the vision screening procedure was quite detailed, it is possible that parents suspected that their children were likely to need spectacles and did not adhere with the referral to avoid this outcome. A qualitative study in England found that the stigma of spectacle wear explained why some parents of 4–5 year old children did not adhere referrals after failed vision screening.Citation36 This might explain why the parents of older children were more likely to comply: the importance of good vision for upcoming first grade may have outweighed the stigma they felt towards spectacle wear.

Comparing referral rates between studies is difficult, since it is highly dependent on the specific population and the screening technique and thus varies greatly in the scientific literature. Previous studies of preschool children using similar methodology, showed a range of 10–20%.Citation37 Furthermore, a previous study in Israel using the same methodology found a referral rate of 24%.Citation32 Ore et al. examined the prevalence of vision and ocular abnormalities in Israeli schoolchildren.Citation38,Citation39 They found a prevalence of visual acuity worse than 6/12 in 29% and 15% of Arab and Jewish first graders, respectively. These children would have been referred according the criteria used in the current study, resulting in a similar failure rate.

Most (57.5%) of the parents who adhered to the referral for a full eye examination reported that their child was not found to have abnormal findings. This high false-positive rate might reflect the prevalence of amblyogenic risk factors in preschool children, over-referral, or a combination of these factors.

The prevalence of refractive amblyopia risk factors may be as high as 21.8% in 3-5-year old children,Citation10 but not all children in this category require intervention. Thus, the current study may have identified children with refractive problems who do not require ophthalmic care. Furthermore, it is not unusual to have a high false-positive rate in universal screening projects with children in preschool and previous rates are comparable (52%Citation22 and 67%Citation23 to the current study (57%). In Germany, the false-positive rate was 67% for kindergarten children who had never had vision problems prior to screening.Citation23 As in the current study, this false positive rate was calculated based on parental reporting, which may have biased the results. In India, a false positive rate of 42% was found for zero to five-year-old children whose parents adhered with the full examination.Citation22 An additional 10% of children who had “true-positive” results, were diagnosed with low refractive errors (<1.0 D cylinder or >0.75 D myopia) and may have been defined as false-positives in the current study. The false-positive rate in that study was based hospital records and therefore may be more reliable.

The high false-positive rate in the current study may reflect the design. It was not designed to assess the sensitivity of the vision screening program. Such a study would involve comparing the results of all the children who failed vision screening to a gold-standard eye examination using cycloplegia. For example, in the Philadelphia school system, nurses screened kindergarten to 8th grade children using visual acuity and all children who failed received a cycloplegic eye examination in a mobile van. Their false-positive rate varied from zero to 44%, with an average of 16%.Citation18

Alternatively, the high false-positive rate in the current study may be the result of over-referral. Indeed, the students may not have had the skills to examine young children which may have resulted in 3% of the children being referred for non-compliance. These children may have complied with a more experienced practitioner. In any screening program, there is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity.Citation40 In a large community wide preschool vision screening program, when the diagnostic procedure is non-invasive (eye examination), and the consequence of false-negatives could be amblyopia, a low sensitivity may be an acceptable price to pay for high specificity. However, since the current study was not designed to test sensitivity and specificity, this cannot be assessed. Therefore, further research must be conducted to determine the factors that led to the high false-positive rate.

There are several limitations to this study. All the children and their families are from the Jerusalem District. Therefore, the results may not reflect the rest of the country nor other places in the world. However, the families included in this study do reflect diverse ethnic groups in Israel, so the results may be applicable to other locations. The data set most likely contained siblings. Since it was analysed anonymously, the dataset was not corrected for sibling pairs and this may have skewed the results.

Ethnicity and socio-economic status were not self-described but based entirely on neighbourhood of residence, so some children may have been misclassified. Furthermore, the secular/religious Jewish category has two populations who might not resemble one another, although many of their characteristics are similar such as education and outlook towards modernity. Only 159 children were classified as high socio-economic status. This is below the sample size required. It is possible that a larger sample of children from high socio-economic status might have changed the results.

Follow up was based on telephone conversations and not on medical records. Thus, some of the children may have been misclassified. In addition, the interviewer presented the parents with an open-ended question regarding barriers. This may have predisposed the parents to answer that they forgot or were busy, and catagorised as a predisposing factor, when in fact another barrier was the primary reason. Future studies should ask the parents from a list of potential reasons, including whether it was difficult for the parents to get an appointment.

The screening examination lasted 20 minutes, so parents may have believed that their child had already received a comprehensive eye examination. However, the parents did receive an oral explanation from the optometrist so this is not likely.

Conclusion

This study found that almost half the parents did not adhere to the referral to a full eye examination, regardless of ethnicity or socio-economic status. Interventions aimed at increasing adherence should involve the importance of vision for learning and the importance of identification of amblyogenic factors at a young age.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Israel Ambulatory Pediatric Association. The authors would like to thank the staff of the Mother and Child Health Centers and Jerusalem District of Health as well as the faculty and students of Hadassah Academic College for their support. The authors would like to thank the parents and children in the Jerusalem District of Health for participating in the vision screening program. The authors thank Deena Rachel Zimmerman for review of barriers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Durr NJ, Dave SR, Lage E et al. From unseen to seen: Tackling the global burden of uncorrected refractive errors. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2014; 16: 131–153.

- Marques AP, Ramke J, Cairns J et al. Global economic productivity losses from vision impairment and blindness. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 35: 100852.

- Naidoo KS, Leasher J, Bourne RR et al. Global vision impairment and blindness due to uncorrected refractive error, 1990-2010. Optom Vis Sci 2016; 93: 227–234.

- Varma R, Tarczy-Hornoch K, Jiang X. Visual impairment in preschool children in the United States: Demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2060. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017; 135: 610–616.

- Pascual M, Huang J, Maguire MG et al. Risk factors for amblyopia in the vision in preschoolers study. Ophthalmology 2014; 121: 622–629 e621.

- Yap TP, Luu CD, Suttle C et al. Effect of stimulus orientation on visual function in children with refractive amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2020; 61: 5.

- West S, Williams C. Amblyopia in children (aged 7 years or less). BMJ Clin Evid 2016; 2016 : 0709. PMID: 26731564; PMCID: PMC4701128.

- Mavi S, Chan VF, Virgili G et al. The impact of hyperopia on academic performance among children: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2022; 11: 36–51.

- Yap TP, Luu CD, Suttle CM et al. Electrophysiological and psychophysical studies of meridional anisotropies in children with and without astigmatism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2019; 60: 1906–1913.

- Arnold RW, Donahue SP, Silbert DI et al. AAPOS uniform guidelines for instrument-based pediatric vision screen validation 2021. J Aapos 2022; 26: 1 e1–1 e6.

- Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study G. Prevalence of myopia and hyperopia in 6- to 72-month-old African American and Hispanic children: The multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology 2010; 117: 140–147 e143.

- Vaisblai E. Vision problem in children and youth: diagnosis and treatment. Israel Knesset Center for Research and Information; 2010.

- American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Vision screening recommendations. Israel Government; San Francisco, Ca. 2014. https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/AAPOS/159c8d7c-f577-4c85-bf77-ac8e4f0865bd/UploadedImages/Documents/vision_screening_rec.pdf

- Gudgel D. Eye screening for children. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2014. Available from: https://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/children-eye-screening

- Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK et al. Vision screening in children aged 6 months to 5 years: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2017; 318: 836–844.

- Donahue SP. The 2017 US Preventive Services Task Force report on preschool vision screening. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017; 135: 1021–1022.

- Pizzi LT, Snitzer M, Amos T et al. Cost and effectiveness of an eye care adherence program for Philadelphia children with significant visual impairment. Popul Health Manag 2015; 18: 223–231.

- Alvi RA, Justason L, Liotta C et al. The eagles eye mobile: assessing its ability to deliver eye care in a high-risk community. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2015; 52: 98–105.

- Mehravaran S, Duarte PB, Brown SI et al. The UCLA preschool vision program, 2012-2013. J Aapos 2016; 20: 63–67.

- Mehravaran S, Quan A, Hendler K et al. Implementing enhanced education to improve the UCLA Preschool Vision Program. J Aapos 2018; 22: 441–444.

- Silverstein M, Scharf K, Mayro EL et al. Referral outcomes from a vision screening program for school-aged children. Can J Ophthalmol 2021 Feb; 56(1): 43–48.

- Ravindran M, Pawar N, Renagappa R et al. Identifying barriers to referrals in preschool-age ocular screening in Southern India. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020; 68: 2179–2184.

- Schuster AK, Elflein HM, Diefenbach C et al. Recommendation for ophthalmic care in German preschool health examination and its adherence: Results of the prospective cohort study ikidS. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0208164.

- Binyaminy B, Bilenko N, Haas EJ et al. Socioeconomic status and vaccine coverage during wild-type poliovirus emergence in Israel. Epidemiol Infect 2016; 144: 2840–2847.

- Stein-Zamir C, Abramson N, Shoob H. Notes from the field: Large measles outbreak in Orthodox Jewish communities - Jerusalem District, Israel, 2018-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69: 562–563.

- Somekh E, Ashkenazi S, Grossman Z. Child healthcare in Israel: current challenges. Turk Pediatri Ars 2020; 55: 57–62.

- Zimmerman DR, Verbov G, Edelstein N et al. Preventive health services for young children in Israel: Historical development and current challenges. Isr J Health Policy Res 2019; 8: 23.

- Shiffer V. The Haredi educational in Israel: allocation, regulation and control. The FloersheimOct. 15ther Institute for Policy Studies; 1999.

- Weissblau E. Data on Orthodox educational system [in Hebrew]. Jerusalem, Israel: The Knesset Research and Information Center; 2012.

- Rashi T. Divergent attitudes within Orthodox Jewry towards mass communication. Rev Commun 2011; 11: 20–38.

- Characterization of geographic areas and classification according to socio-economic status for the population in 2017. Israel Central Bureau of Statistics; 2021.

- Zimmerman DR, Ben-Eli H, Moore B et al. Evidence-Based preschool-age vision screening: Health policy considerations. Isr J Health Policy Res 2019; 8: 70.

- Statistics ICBo. The population of Israel according to area, age and gender, the end of 2017. 2019.

- Lohfeld L, Graham C, Ebri AE et al. Parents’ reasons for nonadherence to referral to follow-up eye care for schoolchildren who failed school-based vision screening in Cross River State, Nigeria-A descriptive qualitative study. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0259309.

- Chung SA, Snitzer M, Prioli KM et al. Reducing the costs of an eye care adherence program for underserved children referred through inner-city vision screenings. Am J Ophthalmol 2021; 86(6): 619–623.

- Bruce A, Sanders T, Sheldon TA. Qualitative study investigating the perceptions of parents of children who failed vision screening at the age of 4-5 years. BMJ Paediatr Open 2018; 2: e000307.

- Kulp MT, Vision in Preschoolers Study G. Findings from the Vision in Preschoolers (VIP) study. Optom Vis Sci 2009; 86: 619–623.

- Ore L, Garozli HJ, Schwartz N et al. Factors influencing prevalence of vision and ocular abnormalities among Jewish and Arab Israeli schoolchildren. Isr Med Assoc J 2014; 16: 553–558.

- Ore L, Garzozi HJ, Tamir A et al. Vision screening among northern Israeli Jewish and Arab schoolchildren. Isr Med Assoc J 2009; 11: 160–165.

- Maxim LD, Niebo R, Utell MJ. Screening tests: A review with examples. Inhal Toxicol 2014; 26: 811–828.

Appendices Appendix A.

Script of interview with parents

Hello,

This is (insert name) calling for the Mother Child Health Center from (city name and neighborhood). On (insert date) your child underwent vision screening at the Mother Child Health Center. Your child received a referral to an ophthalmologist for a comprehensive eye exam.

Did you take the child for a comprehensive eye exam?

If the parents answer yes, ask the following questions:

Where was your child examined? (ophthalmologist, paediatric ophthalmologist, optometrist, HAC)

What date was your child examined?

What were the results of the eye exam?

If the parent answers no, ask the following questions:

May I ask why you did not take your child to the full eye exam as referred?

Do you plan to take your child to a full eye exam in the future? If so, where and when?

May we call you again for follow-up?