ABSTRACT

A current focal point of right-wing populist (RWP) parties across Western societies has been anti-environmentalism and anti-feminism, entangled with their dominant anti-migrant agenda. This clustering of positions overlaps with the conceptual GAL-TAN (Green, Alternative, Liberalist – Traditional, Authoritarian, Nationalist) distinction in voter studies. Still, numerous voters might transcend this distinction, for instance adhering to femonationalism. By taking a feminist ground-up approach, we reveal how nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist attitudes do (or do not) cluster across Western Europe. Our results show that approximately 30% of voters deviate from the GAL-TAN logic, with considerable clusters of citizens combining strong nativism with support for gender equality or moderate nativism with anti-feminism. Further, we estimate the support for RWP parties and show that nativism is core to supporting RWP elites, and anti-environmentalism can provide an additional vote bonus. However, our analysis reveals that the (anti-)feminist and nativist elements of people’s political ideology entail more complex entanglements: both anti-feminist nativist voters and femonationalist voters gravitate to RWP parties. These results imply that feminist quantitative studies are needed to lay bare the average-defying minority groups that can be mobilised to support RWP parties.

Introduction

A most recent focal point of right-wing populist (RWP) parties across Western European societies has been anti-environmentalism and anti-feminism, intermixed with their ever-present and dominant anti-migrant agenda. Some right-wing populist parties might even have moved away from simple nativist identity politics towards complex, multifaceted imaginaries in which nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism inform one another, as for instance seen in Dutch and U.S. elections. This clustering of anti-environmentalist, anti-feminist, and nativist positions overlaps with the conceptual GAL-TAN dimension in voter studies: ethical and emancipatory Traditional stances (e.g. anti-feminism and anti-environmentalism) cluster with Authoritarianism and Nationalism (e.g. nativism) (TAN), while, at the other end of the scale, those who support Green policies tend to support Alternative and Libertarian (GAL) policies too.

The present study asks the question: How do voters combine nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist stances, and to what extent do those attitudinal clusters inform RWP support? Existing works, especially quantitative studies, have devoted far more attention to how especially nativism feeds into RWP support and whether and, in some cases, whether anti-feminist attitudes have an additional impact (cf. De Koster et al. Citation2014; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Citation2002; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015a) than to how these issues (and anti-environmentalism) interconnect. However, this overlooks, for instance, how RWP parties’ racialised and gendered discourses inform one another, and that voters are likely to cast their vote not based on one isolated opinion but on the basis of an intricate, interconnected, and at times even contradictory, belief system. Our overarching contribution to the literature is to theorise beyond the assumption that party preferences are directed by isolated positions. Rather, we empirically study whether and how configurations of interconnected nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist positions shape RWP support.

Building on the feminist tradition, also in quantitative studies, to examine subgroups and minorities in order to better understand society at large, we argue studying average-defying groups promises to help refine our theories on RWP support. In other words, our contribution aims to shed light on the unexpected and complex ways nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist stances might cluster in social reality and inform voting behaviour. While anti-migrant, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist stances of parties and voters might go together some or even most of the time, they can also be disconnected or even contradictory.

For instance, in the most recent European Parliament elections, the French Front National claimed a nationalist and pro-environmentalist agenda, and several RWP parties like the Dutch Partij voor de Vrijheid and the Danish Dansk Folkeparti argue for and even vote in favour of women’s and LGBT’s rights (Akkerman Citation2015; Dudink Citation2017; Puar Citation2007; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015a; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017). Similarly, voter studies show that in some countries anti-migrant attitudes and support for gender+ equality go together and might feed into support for RWP parties (Lancaster Citation2020; Spierings Citation2020b; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015b; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017). Although anti-environmentalist positions are present in far-right policies more generally, anti-environmentalism received little scholarly attention – still, from what we do know, environmentalist positions hardly seem to play a role in voting RWP (Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015b).

Not all RWP parties or electorates might thus combine equally strong anti-migrant, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist stances, despite this prominence from the GAL-TAN scale in the voting literature. Consequently, how citizens are mobilised to vote for RWP parties might be less straightforwardly connected to nativism than assumed in popular and academic debates (cf. De Koster et al. Citation2014; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Citation2002). Unpacking this is the goal of this study. We use a bottom-up approach to lay bare which clusters of attitudes exist in society and whether and how nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism are entangled salient forces that together fuel voting for RWP parties (and other political elites).

We find that a substantial minority of voters (30%) cannot be understood in simple dichotomous GAN-TAN notions, and these help to understand RWP voting. Our results show nativism is key for voting for RWP parties. At the same time, it seems that RWP parties can gain additional votes, also from moderately nativist voters, by taking strong anti-environmentalist positions and by balancing moderately conservative positions on gender equality with fierce ‘pro-gendered’ anti-Muslim positions.

Theoretical Background

Contrary to most studies on public opinion and voting behaviour, this study is not a typical hypothesis-testing study, even though we do formulate expectations based on our analyses of the literature. This study positions itself at the crossroads of (mainstream and feminist) literatures on voter attitudes and the political actor-driven construction of ideological spaces, with a particular focus on right-wing populist parties (RWP parties). We take a bottom-up, inductive approach in assessing how public opinion on anti-feminism, nativism, and anti-environmentalism resembles and informs ideological clusters among the reactionary political elites, allowing for results and combinations we do not expect.

Considering Contested Concepts

Given the purpose of our study, we first provide some demarcation of how we use the terms central to this paper.

First, as feminist scholars noted, ‘anti-feminism’ refers to a project of rolling back feminist accomplishments as well as halting current endeavours for further feminist progress, i.e. opposition to (more) gender equality and sexual liberalisation (e.g. Verloo Citation2018). In line with previous feminist works, we conceptualise feminism in dynamic terms, which accounts for the possibility that support for specific degrees and forms feminism can vary by issue and context (also given the status quo), although all involve furthering gender equality, women’s empowerment, and/or sexual liberalisation (see Glas and Spierings Citation2019; Walby Citation2011). Anti-feminism, in the broadest sense, then refers to supporting the status quo or objecting to pushes towards aspects of greater gender equality, women’s empowerment, or sexual liberalisation, even if the levels of equality are relatively high already.

Second, ‘nativism’ (Inglehart Citation1997; Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017) refers not solely to the objection to migrants settling in a country, or to multiculturalism, or to a very clearly specified ethnic or racial group. ‘Nativism’ refers to imagining an ideal society based on a notion of a ‘native’ population, which is largely fictious and generally ill-defined. This makes it rhetorically flexible, as it does appeal to a common understanding of what makes people fall beyond the confines of ‘native’, which can refer to skin colour, race, ethnicity, migration background, religion, and more.

Last, we use a dynamic and flexible demarcation of anti-environmentalism, which includes the denial of the empirical grounds of climate change, the devaluing or deprioritising of the environment, and the raising of practical objections or resistance to environmentalist policies. What is (anti-)environmentalist thus depends on the larger context; for instance, what we consider pro-environmentalist now (e.g. being in favour of certain forms or energy production), might turn anti-environmentalist later (e.g. when newer techniques allow further progress).

Each of the projects referred to above (migration, feminism, environmentalism) can and has been framed as elite-driven. This is directly linked to the populist Manichean distinction between the evil elite and the good common people (see Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017; Spierings Citation2020a). By framing a project as elitist, it is by definition evil. However, accomplishments of the past – that are largely internalised among the larger public and considered normal – can still be framed as needing to be defended. This stresses that both the rolling back of existing accomplishments and the defence of the status quo are part of understanding how anti-feminist, nativist, and anti-environmentalist attitudes feature in public belief systems. Phrased slightly simplistically: populists might defend gender equality (as is), but will be against feminism or genderism.

Multidimensional Political Space

There are good reasons to expect that anti-feminism, nativism, and anti-environmentalism will generally cluster together among (RWP) voters, as political space is generally conceptualised by emphasising two core dimensions across Western Europe and beyond: the economic left-right dimension and the cultural dimension with a green, alternative, libertarian (GAL) pole and a traditional, authoritarian, nationalist (TAN) pole (Kitschelt Citation1994; Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Citation2002). Moreover, RWP parties often discursively connect anti-feminism, nativism, and anti-environmentalism to create their imaginaries. For instance, feminist scholars have argued that RWP elites have been argued to mobilise certain anti-environmentalist concerns to argue for a gendered and racialised status quo (e.g. Anshelm and Hultman Citation2014). Most generally we thus expect that: most voters will combine GAL or TAN attitudes.

At the same time, this straightforward unidirectional entanglement will probably not hold for all parties and voters. However, in quantitative studies, such average-defying minority groups tend to be sidelined. In line with feminist studies, we highlight this diversity and emphasise minorities’ experiences.

There are several reasons to expect that quite substantial minorities of GAL-TAN defying voters exist. For instance, recent work has shown that (growing) pockets of sexually-modern nativist voters exist (Lancaster Citation2020; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017), and that under certain circumstances they might vote for RWP parties (De Koster et al. Citation2014; Spierings Citation2020b; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015a; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017). While this paper does not argue against the predominant conceptualisations of political space, it does posit that a focus on these classic dimensions is likely to overlook more complex voter configurations. Here, we set out to assess how anti-feminism, nativism, and anti-environmentalism are entangled in more complex ways too, which seems important in the face of the intricateness of right-wing populist party support, anti-feminist shifts, and latent positions that might be mobilised in favour of these political projects. In brief, we thus expect that: there are pockets of voters who cross over GAL-TAN lines.

Combining Anti-Migrant and (Anti-)Feminist Positions

In what ways might the distinction between the green, alternative, libertarian (GAL) and the traditional, authoritarian, nationalist (TAN) political positions be more complex than existing studies lead us to expect? To answer this question, we start by looking at gender and sexuality in RWP. The RWP family is the clearest and most extreme nativist party family in Western Europe, and across countries, it is positioned at the gender-conservative end of the spectrum (e.g. Akkerman Citation2015; De Lange and Mügge Citation2015). However, a closer look at the literature clearly shows ambiguities in the anti-feminist stances that RWP parties adopt (e.g. Dietze and Roth Citation2020), which clearly deviates from the ‘TAN’-clustering.

Rhetorically at least, some RWP parties employ homosexual people and women as symbols to argue in favour of nationalism, for instance depicting as Muslim men a hypermasculine threat to women and homosexuals (e.g. Chaudhury Citation2021; Norocel et al. Citation2020). Even more so, some RWP parties adopt gender progressive stances that cannot be fully explained by such homonationalism or femonationalism (Akkerman Citation2015; Dudink Citation2017; Fiers and Muis Citation2020; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017; Spierings Citation2020a). RWP parties’ objection to feminist goals is thus not absolute.

Rather than opposing the substantive goals of all feminist projects, resistance against feminist goals is regularly more a result of ‘anti-genderism’ and thus an embodiment of a more populist resistance against political elites going against the people. Consequently, most RWP parties do not argue that current accomplishments need to be rolled back. RWP parties might actually consider the already accomplished forms of de jure or de facto equality as part of normality and what is native to the culture. Still, RWP parties will argue that a feminist project or ‘genderism’ goes against the common will if it is not part of normality yet (see Spierings Citation2020a).

For instance, affirmative action or policies changing the sexual binary status quo are resisted by basically all RWP parties. Consequently, these issues do not fit a right-wing populist platform and are less likely to co-occur with nativist stances. However, general support of sexual equality might be genuinely combined with xenophobic positions as for instance same-sex couples have been allowed legal union for over 30 years in some European countries (in 1989, Denmark was the first to grant same-sex couples legal partnership) and combating discrimination based on sexual orientation is explicitly part of the 1999 Treaty of Amsterdam. Not surprisingly, the public opinion literature already shows that European people combine general support for LG-equality and nativist attitudes (De Koster et al. Citation2014; Lancaster Citation2020; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017).

It is against this backdrop that we aim to shed light on the questions: (a) whether and to what extent pockets of voters combine feminism with nativism, and, if so (b) to what extent any feminist-nativist voters are drawn to RWP parties.

Bringing in Anti-Environmentalism

On how anti-environmentalism ties into anti-migration and anti-feminist positions, we can again rely on RWP parties’ imaginaries and the GAL-TAN classification – they strongly overlap (e.g. Clements Citation2012; Inglehart Citation1997) – but the above discussion on bringing in the populist element should not be overlooked. As is the case with feminism and gender equality, many citizens are likely not to object to taking some care of the environment and do think that puppies should not be maltreated – this is all part of today’s normality and native culture – but they do object to the state or political elites who impose windmills upon them, so they consequently reject certain environmentalist stances which are new and less common (Hochschild Citation2018). In that sense, considering the entanglement of anti-environmentalism with right-wing populism lays bare an important tension. Populism is not so much about what one wants; it is almost inherently nostalgic, and conjoined with radical right politics it becomes a political ideology that refers to an imagined nation that normalises much of the state of affairs and therewith the moral correctness of the people. So, climate change can be considered important, but current environmental problems cannot be the people’s fault, and they should not change their current behaviour as they are morally good. That argument holds similarly for the tension between supporting gender equality but not expecting behavioural changes (Spierings Citation2020a).

Again, there is clear diversity in this respect within the RWP party family. On the one hand, there is Trump, and, for instance, the newest Dutch radical (or extreme) right party Forum voor Democratie that strongly presented itself in contrast to scientific consensus on the issue of climate change (e.g. De Pryck and Gemenne Citation2017). On the other hand, arguments have been made for Right-Wing Green politics or Green liberalism (Wissenburg Citation2001), and Christian Democracy has been linked to stewardship over our environment (Dubos Citation2006). Political reality has also seen coalitions between the Greens, Christian Democrats and Liberal-Democrats in multiple German regional governments. Moreover, and arguably more centrally to this paper, Italy’s Five Star Movement and Austria’s Liste Pilz have been considered difficult to classify as they combine populist, nativist and green positions (e.g. Jacobs, Sandberg, and Spierings Citation2020) and the Dutch PVV has a self-declared animal-rights activist among its most prominent MPs, who goes beyond anti-Islam animal rights in his politics. Therefore, we also ask to what extent (a) environmentalism is combined with anti-feminism and nativism among pockets of voters, and, if so, (b)whether any green nativists are drawn to RWP parties.

Altogether, we argue that it is not outrageous to think that some parts of the population are nativist and anti-feminist but still relatively environmentalist, or that they are nativist and climate sceptic but relatively progressive in terms of gender equality.

Voting for Right-Wing Populists

The literature is quite clear that of the different political attitudes citizens can take, the main distinction between RWP voters and others are anti-migrant or nativist attitudes (De Koster et al. Citation2014; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Citation2002). Research that looks into the role of gender attitudes or environmentalism showed little to no impact of these at all (e.g. Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015a). It is on nativism that RWP parties are in competition with the mainstream right, of which the latter’s move to the nativist right is a testimony (Rooduijn, De Lange, and Van der Brug Citation2014). A similar argument cannot be made on gender traditional or anti-feminist positions. This part of the party system was populated by conservative and Christian Democratic parties already, and anti-environmentalism seems to have coincided with Christian Democrats’ defence of farmers and liberal conservatives’ economic non-intervention and pro-industry positions. Therefore, this paper also asks whether the predominance of nativism in determining who votes RWP means that anti-feminist and anti-environmentalist attitudes do not matter at all?

Some recent results do indeed suggest that, for instance, in a broader sense moral progressiveness or religiously-inspired orthodoxy do not shape a vote for RWP parties, even when taken into consideration in combination with nativist views (De Koster et al. Citation2014). At the same time, others have shown that the sexually-modern nativist part of the potential RWP electorate is growing, although this was not linked to the actual box ticked in the voting booth but only to party closeness (Lancaster Citation2020). Together these studies suggest that voters recognise that RWP parties are not singularly on the TAN side of the GAL-TAN scale. RWP parties might thus appeal to broader nativist electorates even though nativist attitudes remain a dominant or even close-to-necessary voting condition.

Translated to the paper at hand, we expect nativism to be the main fault line explaining voting for RWP parties. If the voters are also anti-environmentalist and anti-feminist, the RWP parties are certainly likely to be the predominant party. However, if citizens combine nativism with pro-gender and sexual equality attitudes, more competition with liberal-conservative parties might exist. RWP parties can position themselves more liberally on gender and sexuality, while more liberal Conservative-Liberal parties have a more long-standing and credible position on that regardless of the RWP’s stances, but Conservative-Liberal parties are on average less clearly nativist (Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017). In such cases, not extremely nativist voters might consider both party families. More generally, we can thus expect that if citizens are nativist but not clearly anti-feminist or anti-environmentalist this might redirect them from the RWP parties, at least to some extent. We expect this not because RWP parties cannot combine such stances, but because other parties do too, making the RWP less unique in that part of the party system. It should be noted, though, that this competition might be advantageous for RWP parties: they might not lose the classic TAN voter, but might draw voters from other anti-migrant parties by moderating their other views.

Methods and Data

This study uses the most recent wave of the European Values Survey (EVS 2017-18), including a plethora of items on feminist, environment, and nativist attitudes. The EVS uses random sampling (EVS Citation2020) from which we selected Austria, Denmark, Great Britain, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland (23,828 respondents; see Appendix A.1) – West European countries with RWP parties present in the data.

RWP Support

Right-wing populist support was measured by ‘the most appealing political party’, of which we consider 26 to be RWP (Appendix A.1). We compare these to Christian parties and (liberal-) conservative parties. The ‘other’ category captures support for non-RWP, non-Christian, and non-conservative parties as well as respondents who indicated they did not feel close to any party at all. Missing values were included separately.

Anti-Migrant, Anti-Feminist, and Anti-Environmentalist Attitudes

Nativism was gauged using twelve items that span diverse religious, racial, and ethnic outgroups. First, on a five-point scale (from ‘very good’ [1] to ‘very bad’ [5]), respondents were asked what they believed the impact of immigrants to be on the development of their country. Four additional items asked respondents to place themselves on ten-point scales on four issues: to what extent immigrants (a) take jobs away from nationals; (b) make crime worse; (c) are a strain on a country’s welfare system and (d) should not maintain their distinct customs and traditions. We also included respondents’ agreement, on a five-point scale, that employers should prioritise natives over immigrants in times of job scarcity. A further four items asked respondents to indicate what people they would not like to have as neighbours, including people of a different race; immigrants or foreign workers; Muslims; and Jews. Finally, two items were included on the extent to which respondents reported trusting people with another religion and another nationality [on four-point scales].

Anti-feminism was tapped using thirteen items. The first seven question respondents’ views on gender equality on four-point scales: children suffer when mothers work; what most women really want is a home and children; family life suffers when women have full-time jobs; a man’s job is to earn money, a woman’s is to look after the home and family; men are better political leaders than women; university education is more important for boys than girls; men are better business executives than women. An additional item questions respondents’ agreement that when jobs are scarce, men should have a greater right to a job than women (five-point scale). Next, we include items on sexual liberalisation: respondents’ beliefs that homosexuality, abortion, and divorce are justifiable (ten-point scale); whether respondents objected or not to having homosexual neighbours; and to what extent respondents believe homosexual couples to be equally good parents as other couples (five-point scale).

The six items on anti-environmentalism are more limited and some tap more into efficacy.Footnote1 The first five items asked respondents to what extent they agreed with the following: I would give part of my income to prevent environmental pollution; it is too difficult for someone like me to do much about the environment; there are more important things to do in life than protect the environment; there is no point in doing what I can for the environment unless others do the same; and many claims about environmental threats are exaggerated (five-point scales). The final item asked to select one of two statements: ‘protecting the environment should be given priority, even if it causes slower economic growth and some loss of jobs’ or ‘economic growth and creating jobs should be the top priority, even if the environment suffers to some extent’.

Higher scores reflect greater nativism, anti-feminism, or anti-environmentalism. The latent class analyses conducted (see below) can process missing values, leading to no exclusions. Descriptive statistics are shown in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Analytical Approach

To identify attitudinal clusters, we use clustering analysis. This approach should be seen as an inductive first exploration rather than a definitive final test. We hope to start rather than finish a discussion highlighting the complex clustering of nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist attitudes and its consequences.

To identify attitudinal clusters, we use Latent Class Analyses (LCAs). These analyses group respondents with similar attitudinal profiles together into clusters. This may for instance lay bare a cluster of respondents who are simultaneously nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist and a separate cluster of respondents who are nativist and anti-environmentalist but not anti-feminist. So, the major advantage of these analyses is that they fit our aim to study respondents’ attitudes simultaneously and assess whether in terms of RWP support their whole tells us more than the sum of their parts.

In more technical terms, the LCAs take each respondent’s answers to the 31 items and iteratively find clusters (‘classes’) throughout the data; respondents are then assigned to the class they are most likely to belong to, given their answers. The LCA models show, for each class, the typical answers to the items included. The models thus demonstrate the likelihood respondents report a certain amount of nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism assuming they are members of a given class. Another major advantage of the LCA models is that we do not have to set cut-off points. So, we do not have to decide, for instance, how nativist respondents have to be to be in a nativist cluster. Rather, the LCA’s identify clusters that optimally reduce the variation in the data, and the outcomes show how nativist (and anti-feminist and anti-environmentalist) respondents in each cluster are.

Instead of basing our attitudinal profiles on arbitrary pre-set cut-off points, the results of the LCAs are based on the number of classes added to the model. The researcher thus specifies the number of clusters the models should distinguish, which could be seen as the major disadvantage of LCAs, because the choice for one model over another remains a discussion (for details on why we selected our particular LCA model, see Appendix 2). We estimated models with between one and ten classes and selected our final model on theoretical and empirical grounds. Empirically, AIC and BIC values showed models with four, five, six, or seven classes fit the data best. Theoretically, we opted for a model that disentangled the most theoretically meaningful clusters of attitudes for this paper’s purposes. As the six-class model showed the most different configurations of nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism,Footnote2 we selected this model (full models: Appendix 2; distribution of classes per country: Appendix 3).

Finally, to provide insights into how these six attitudinal clusters feed into party preferences, we estimate multinomial models on vote choice. We use RWP parties as the reference category to be able to compare RWP supporters to both Christian and (liberal-)conservative party voters, as well as voters for other parties. We estimate single-level models which account for contextual differences between countries. All models are controlled for gender, age, education, marital status, employment status, and migration status (). Additionally, we create linear scales of nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism by re-coding all items to range from 0 to 1 and averaging them per scale (1 signifying maximal nativism, anti-feminism, or anti-environmentalism),Footnote3 and add these to the model to ascertain whether the combinations of attitudes in the clusters add to the independent effects of nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism as generally used in the voting literature.

Results

Attitudinal Clusters

In what ways do European voters combine nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmental attitudes? In the most general terms, our latent class analyses indicate that while conventional theories of political space are well-suited to capture the belief systems of the majority of people, a non-negligible minority of approximately three in ten people is disregarded when we only focus on ‘GALs versus TANs’.

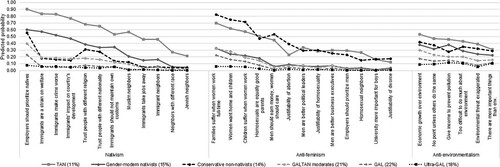

Four of our six classes in (for the full model, see Appendix 2; for the distribution of classes per country, see Appendix 3) align rather well with the GAL-TAN scale: citizens in these clusters are like to score consistently high, consistently low, or consistently moderate across the three groups of attitudes, i.e. nativism, anti-feminism and anti-environmentalism.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities to be nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist per class.

Of these, the first two groups of citizens – the GAL group and the ultra-GAL group – are very likely to give progressive answers with regard to migration, gender equality and environmentalism. Together, they total 40% of the sample. The ‘ultra-GAL’ group (18%) is clearly opposed to nativism and supports feminism and anti-environmentalism. They have probabilities below 10% to answer clearly positive on all items; only when it comes to certain anti-environmentalist attitudes related to a lack of efficacy or prioritising other issues, they go just above 0.1. The ‘GAL’ group (22%) also fits the GAL end of the spectrum – hence the label – although it is slightly less progressive across the issues and particularly so on nine items across the three themes, going above 0.1. If there is a pattern to this it seems that the GAL group compared to the ultra-GAL group is somewhat more worried about employment and economic consequences and tie children’s welfare to having a parent at home; in other words, they are somewhat less progressive when the items are not about a general principle but about a practical trade-off between groups. Compared to all others, they are still highly progressive across the board, but this difference indicates that worries about children’s welfare and employment (justly or not) might provide threats to progressive attitudes. Additionally, the model finds one group of ‘GALTAN moderates’ (21%) that falls in the middle of the pack across the three issues, with consistently being the third or fourth group in terms of the predicted probabilities to be nativist, anti-feminist, or anti-environmentalist.

The TAN group is the first of three clusters that is most interesting for the purposes of this study. This group of cultural conservatives (11%) is strongly nativist, anti-feminist, and anti-environmentalist. This is the group of people, in other words, that embodies the TAN end of the spectrum and would be theorised to be the archetypical RWP voter, not in the least because they are the most nativist of all, including the highest prevalence of racist and anti-Semitic tendencies and the lowest social tolerance. However, as the prevalence of 11% already suggests, it is unlikely that it is just this group that votes RWP. What do the other two groups look like?

The model specifies two groups of respondents who are on the TAN end of the spectrum on two of the three themes but less so on the last one. ‘Gender-modern nativists’ (15%) represent a group found and discussed in previous work too (Lancaster Citation2020; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017). Although slightly less strongly than the TAN group, Gender-modern nativists combine pretty strong nativism (but not blatant racism or anti-Semitism – this seems a line of demarcation) with distinct support for gender equality (and rather moderate, conservative-leaning, positions on environmentalism). These voters may thus be mobilised by RWP parties’ messages of nativism and homonationalism and femonationalism. Gender-modern nativists are on the supportive side of feminist issues across the board, including issues on equal rights, division of labour, ethical issues, and equality of homosexual citizens. Interestingly, although they are somewhat less unconditionally supportive when the issues relate to parenthood, Gender-modern nativists’ progressiveness includes the previously more controversial issues like homosexuality and abortion. This signifies that these issues have indeed been normalised across Western Europe and can coincide with nativism, as they do for about one in seven of our respondents and over half of the respondents in either one of the nativist groups. Unfortunately, no items are included that tap into the current ‘culture wars’ regarding gender fluidity, transgender people, quotas, and affirmative policies. It would be our expectation that this group of Gender-modern nativists is less conservative on those issues than on the issues included, while for instance the ultra-GAL is expected to be similarly progressive on the non-included items.

The final group of respondents that is conservative on two of the three themes, we labelled ‘Conservative non-nativists’ (14%). They strongly oppose feminism and environmentalism but are moderately and inconsistently nativist. They support nativism markedly less than the TAN and Gender-modern nativist groups. Yet on a few nativist items, Conservative non-nativists are rather closer to the nativist clusters, most particularly on prioritising natives and distrust of outgroups. ‘Non-nativist’ thus refers to not being strongly nativist, not to being anti-nativist. Conservative non-nativists’ opposition to feminism is about as strong as the TAN group’s and on some items even stronger. In a way, Conservative non-nativists’ opposition seems more volatile with specifically strong feelings about abortion and renegotiations of femininity as motherhood, which suggests that this group has a strong Christian moral, also with respect to holding a somewhat more merciful positions towards migrants.

In terms of our general expectations and questions posed in the first half of this paper, we conclude that while most voters do seem to fit GAL-TAN distinctions, there are non-negligible pockets of voters who do not fit conventional theories of political space. Among these, as expected, there are voters who combine nativism and anti-environmentalism with feminist stances. However, counter to our expectations, our analyses do not lay bare a group of green nativist anti-feminists.

Party Preferences

Having established the different attitudes-based clusters, we now move to the questions of how they link to voting RWP (versus other (right-wing) parties) and whether the former is fully driven by nativism. To assess this, we estimate multinomial models that predict party support, first without the nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism scales (Model 1) and then including them (Model 2).

First, the TAN group, as expected, is the most likely to vote for an RWP party. Model 1 shows that the TAN group is more likely to vote for an RWP party (than a Christian, (liberal-)conservative or other party family) compared to the Ultra-GAL group. As a robustness test, we also estimated the models using the GALTAN moderates as the reference category, which leads to the same results.Footnote4

Interestingly, also Gender-modern nativists, who occupy relatively feminist stances, seem to be drawn more to RWP parties (than Christian, conservative, or even other, left-wing parties) than members of the Ultra-GAL group are. Additional models show this holds for men and women. This implies that within their attitudinal configuration of feminist anti-environmentalist nativism, Gender-modern nativists are swayed by RWP parties’ nativist (and maybe anti-environmentalist) discourses and either prioritise those over there more feminist concerns or racialise the feminist concerns making this about migration and Islam. Gender-modern nativists’ votes for RWP parties are noteworthy, because these (a) strengthen relatively gender traditional RWP parties (Akkerman Citation2015; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015b) and (b) facilitate coalition formation whereby feminist issues are generally sidetracked and anti-feminism is put on the table, because RWP parties by-and-large gravitate towards right-wing coalitions which often include (religious) conservative parties.

Third, also Conservative non-nativists are more likely to opt for an RWP party compared to Christian, conservative, or other parties than Ultra-GALs.Footnote5 This implies that Conservative non-nativists simply take RWP parties’ nativism into the bargain even though it does not fit their own belief system that well (they are generally more centrist on the issue of migration). Doing so, this group does have the potential to strengthen the anti-migrant politics in Europe. However, the centrist nativist stances of the Conservative non-nativist group do seem to push them relatively more toward Christian parties (vs RWP) compared to GALTAN moderates, even though the former group is somewhat more nativist. This implies that for conservatives who are moderately or lowly nativist RWP parties are a serious option, but maybe mostly if no Christian conservative parties are available. As such, this group indicates that for some pockets anti-feminists can lean towards RWP parties even though they do not support their RWPs nativist agenda so clearly. Still, by and large, our findings indicate that nativism is a key driver of the RWP vote, and nativism seems far more influential than anti-feminism in pushing people towards RWP parties.

This proposition suggests, however, that it might be almost fully nativism that explains RWP voting. If that were so, the most nativist people within, for instance, the cluster of conservative non-nativists and GALTAN moderates should be responsible for the ‘in-between’ degree of voting in those clusters. In other words, as the likelihood to vote for an RWP party map rather well on the degree of nativism in the clusters, it might actually be that nativism drives these results, not the specific combinations of attitudes. If so the impact of the cluster should largely disappear when we include the indices for nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism (Model 2).Footnote6

The model shows that anti-environmentalist voters, in general, seem to prefer a (liberal-)conservative party over an RWP one (which makes sense considering the ‘economy vs environment’ discourse) (b = 0.56), and that anti-feminist voters generally go for a Christian party over an RWP party (b = 2.60). Crucially here, it is striking that when nativism, anti-feminism, and anti-environmentalism are simultaneously added to the model (see Model 2 in ), only nativist stances consistently push voters toward RWP parties (over Christian, Conservative, and other parties), and it is this variable that causes the changing effects of the clusters (see Appendix 4). So indeed, nativism is more key to voting RWP than anti-environmentalism and anti-feminism. However, the cluster variables remain significantly related to voting RWP parties over other ones, suggesting that the specific combinations of attitudes towards gender equality and the environment play their part.Footnote7 Two important patterns are clearest in this respect.

Table 2. Direct multinomial models predicting vote preference (PRW = ref).

The first four clusters show coefficients rather similar to each other in Model 2, which we can interpret based on what these clusters entanglements share. They vary strongly in terms of anti-feminism but are all relatively anti-environmentalist (see ). It seems that among those who are moderately to strongly nativist, anti-environmentalists add to the likelihood to vote for RWP parties (but slightly less clearly so compared to liberal-conservative). By and large, these results reflect the populist ideology that the people are morally good, i.e. they cannot cause climate change or be held responsible for solving it (cf. Mudde and Kaltwasser Citation2017; Spierings Citation2020b). Anti-environmentalism might deliver RWP parties additional votes, while the electoral risks are low as no substantive cluster of green nativists was found.

Secondly, after accounting for the above, we found that the gender-modern nativists and the conservative cluster which is moderately nativist gear more strongly towards voting RWP than liberal conservatives and in the former case than Christian parties too, despite these clusters being opposites regarding their (anti-)feminism.

From the gender-modern nativist voters, the RWP seems to get a vote bonus on top of the votes they get from their nativism. A logical interpretation which fits feminist theorising of femonationalism and our discussion of the clusters above, is that these voters are experiencing an even stronger threat from ‘non-natives’. Non-natives might be considered to threaten the degree of gender equality that has been reached in Western Europe, which is important to gender-modern nativists.

The conservative non-nativist cluster, however, is more likely to pick up upon the relatively gender-conservative position RWP parties take on the non-racialised gender issues (see Akkerman Citation2015). This cluster of conservatives is moderately nativist and apparently to them the most salient issue currently is the ‘unnatural stress on gender equality’, i.e. they are most prominently anti-feminist and in many party systems the RWP parties is the most conservative of the main parties (certainly if no main Christian party is present).

These two clusters show the seemingly contrasting roles that racialised gender equality (femonationalism) and anti-feminism play. These results echo the complex gender-balancing act of RWP parties and would not be picked up upon by standard voting models with linear variables as they cancel each other out.

Conclusion and Discussion

Nativism seems core to RWP party preferences (De Koster et al. Citation2014; Spierings and Zaslove Citation2015a; Spierings, Lubbers, and Zaslove Citation2017). At the same time, holding anti-environmentalist attitudes can lead to additional incentives among the more nativist voters. That entanglement still fits the GAL-TAN dichotomy. However, the (anti-)feminist and nativist parts of people's political ideology show more complex entanglements. Non-negligible pockets of voters cross over the GAL-TAN spectrum, and both more anti-feminist nativist voters and femonationalist voters gravitate to RWP parties over other right-wing parties. This echoes RWP parties’ claims to defend society simultaneously against external threats to Western gender equality and against internal threats from feminist elites ‘pushing it’ too far.

These insights carry different implications for feminist and related scholarship on RWP support. First of all, our results show that minorities that defy averages should not be overlooked. Thirty per cent of the electorate does not fit simple GAL-TAN notions, which means that this group should not be overlooked by quantitative voter studies (cf. Ivarsflaten Citation2005; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Citation2002); studies delving deeper into those voter minorities are important to shed light on the complexity of how people combine seemingly unrelated stances and the ‘irrationality’ of voting. Second, our findings suggest that feminist nativist voters do not only exist but that are also mobilised by RWP parties’ racialised gender stances. This has real-life implications for gender equality policies. As part of the feminist electorate seems to wind up voting for these parties, which generally form coalitions with right-wing parties and consequently support conservative policy-making beyond these voters’ femonationalist concerns. For the broader literature on anti-feminism and opposition to gender equality (see Verloo Citation2018) this suggests attention should be paid not only to stances on gender and feminism, but also to the prioritising of it. Moreover, the results we found for conservative moderately nativist voters, at the same time stresses the risk of highlighting the more general anti-feminist signature of this party, as that actually seems to draw votes to the RWP parties.

Third, the seemingly contradictory relationship between (anti-)feminist attitudes and supporting RWP parties can inform feminist theory on the legitimisation of gender differences. For instance, feminist theories have contested ‘natural womanhood’ (e.g. Haraway Citation1987), but in RWP’s discourse it is not so much naturalisation, but normalisation that is at play. RWP elites do not provide a universal ontology but frame what is ‘normal’ in terms of the heartland and true identity of the native population, which can differ between countries (or: nations). As such, the quest for firmer foundations, as ascribed to RWP elites by feminist scholarship (Paternotte and Kuhar Citation2018) can actually end in an inherently unstable or ambiguous ‘true native identity’ which is particularly grounded in what is considered gender normal for the native culture (e.g. Norocel Citation2015) and thus morally correct at a certain spatiotemporal location. Consequently, current RWP politics uses less of a naturalistic or biological discourse about gender or race, asking for different responses than more classic forms of (entangled) racism and sexism.

Our findings also raise some follow-up questions. First, the results show that nativism can be mobilised in different ‘gendered ways’ but also be overwritten by it. Similarly, we suggest that anti-environmental stances might provide a bonus. However, studying the actual linkage between parties and voters is beyond our scope. For instance, how do voters perceive these parties and how do media frame these parties in terms of the interlinkage of RWP parties’ extreme nativist and other programmatic positions?

Second, and pivotal for understanding the impact of the voting dynamics we found, RWP parties are the potential government partner of the least anti-environmental and more gender conservative parties: Christian democrats and conservative(-liberals). Even if RWP parties are actually more moderate on some gender and environmental issues than their right-wing partners, those positions get lost in government formation, the more so because voters will not punish them for this, given nativism’s salience. Due to this saliency of nativism as a subdimension of the cultural GALTAN axis and the de- and re-alignment of the European party system (e.g. Kitschelt Citation1994), particularly the gender progressive positions among the public is mal-represented in policymaking.

Lastly, and related to our first follow-up, the current literature hardly delves into public opinion minorities who combine seemingly contradictory stances. For instance, we showed substantial clusters of gender progressive nativists exist across Europe; doing so we draw attention to questions about who these people are, to what extent they are socialised in certain intermediary societal groups, and how they perceive feminism. For now, we conclude that particularly gender-modern nativist and gender-conservative non-nativist exist and that the complex entanglement of particularly (anti-)feminism and nativism sheds additional light on RWP politics, although nativism remains at the heart of it.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (85.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the constructive comments of two anonymous reviewers.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this paper (European Values Study 2017) are available at https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Niels Spierings

Niels Spierings is Associate Professor at the department of Sociology, Radboud University. His research interests include political behaviour, gender and sexuality, populism, social media, Islam, migration, democratic politics, and quantitative, qualitative and feminist research methods. On these topics he has published journal articles and monographs. In 2015, he co-edited a special issue on gender and the populist radical right in Patterns of Prejudice with Andrej Zaslove.

Saskia Glas

Saskia Glas is Assistant Professor at the department of Sociology, Radboud University. Her research interests include socio-political attitudes, gender and sexuality, Islam, migration, context-dependency, and survey methodology. On these topics she has published journal articles in, among others, European Sociological Review, International Migration Review, and Social Forces.

Notes

1 We assume that stating human action matters little is used to legitimise the issue’s perceived unimportance.

2 A seven-class model shows no pivotal new cleavage.

3 For R’s Polca variables started at 1 was required.

4 Additional models, e.g. for men and women separately, are available upon request.

5 However, compared to GALTAN moderates, conservative non-nativists are more likely to vote for a Christian party over a RWP one.

6 Formally, one cannot directly compare different multinomial models; however as significant effect on the clusters remain, we can certainly claim that their effects are not fully explained.

7 Including nativism quadratically to capture non-linearities does not change results substantively.

References

- Akkerman, Tjitske. 2015. “Gender and the Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Policy Agendas.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1-2): 37–60.

- Anshelm, Jonas, and Martin Hultman. 2014. “A Green fatwā? Climate Change as a Threat to the Masculinity of Industrial Modernity.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 92 (2): 84–96.

- Chaudhury, Proma. 2021. “The Political Asceticism of Mamata Banerjee: Female Populist Leadership in Contemporary India.” Politics and Gender, 1–36.

- Clements, Ben. 2012. “Exploring Public Opinion on the Issue of Climate Change in Britain.” British Politics 7 (2): 183–202.

- De Koster, Willem, Peter Achterberg, Jeroen Van der Waal, Samira Van Bohemen, and Roy Kemmers. 2014. “Progressiveness and the New Right: The Electoral Relevance of Culturally Progressive Values in the Netherlands.” West European Politics 37 (3): 584–604.

- De Lange, Sarah, and Liza Mügge. 2015. “Gender and Right-wing Populism in the Low Countries: Ideological Variations Across Parties and Time.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1-2): 61–80.

- De Pryck, Kari, and François Gemenne. 2017. “The Denier-In-Chief: Climate Change, Science and the Election of Donald J. Trump.” Law and Critique 28 (2): 119–126.

- Dietze, Gabriele, and Julia Roth. 2020. “Right-wing Populism and Gender: A Preliminary Cartography of an Emergent Field of Research.” In Right-Wing Populism and Gender. European Perspectives and Beyond, edited by Gabriele Dietze, and Julia Roth, 7–21. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Dubos, René. 2006. “Franciscan Conservation Versus Benedictine Stewardship.” In Environmental Stewardship, edited by Robert James Berry, 56–62. London: T&T Clark International.

- Dudink, Stefan. 2017. “A Queer Nodal Point: Homosexuality in Dutch Debates on Islam and Multiculturalism.” Sexualities 20 (1-2): 3–23.

- European Values Study EVS. 2020. “European Values Study EVS 2017: Methodological Guidelines.” GESIS Papers 2020/13. Köln. https://doi.org/10.21241/ssoar.70110.

- Fiers, Ruud, and Jasper Muis. 2020. “Dividing Between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’: The Framing of Gender and Sexuality by Online Followers of the Dutch Populist Radical Right.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 4 (3): 381–402.

- Glas, Saskia, and Niels Spierings. 2019. “Support for Feminism among Highly Religious Muslim Citizens in the Arab Region.” European Journal of Politics and Gender 2 (2): 283–310.

- Haraway, Donna. 1987. “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s.” Australian Feminist Studies 2 (4): 1–42.

- Hochschild, Arlie. 2018. Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York: New Press.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, and Carole Wilson. 2002. “Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions on European Integration?” Comparative Political Studies 35 (8): 965–989.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth. 2005. “The Vulnerable Populist Right Parties: No Economic Realignment Fuelling Their Electoral Success.” European Journal of Political Research 44 (3): 465–492.

- Jacobs, Kristof, Linn Sandberg, and Niels Spierings. 2020. “Twitter and Facebook: Populists’ Double-barreled gun?” New Media and Society 22 (4): 611–633.

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lancaster, Caroline. 2020. “Not so Radical After All: Ideological Diversity Among Radical Right Supporters and Its Implications.” Political Studies 68 (3): 600–616.

- Lubbers, Marcel, Mérove Gijsberts, and Peer Scheepers. 2002. “Extreme Right-wing Voting in Western Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 41 (3): 345–378.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Kaltwasser. 2017. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Norocel, Ov Cristian. 2015. “The Panoptic Performance of Masculinity for the Romanian Ethno-Nationalist Project: Disciplinary Intersections in Populist Radical Right Print Media.” DiGeSt. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies 2 (1-2): 143–156.

- Norocel, Ov Cristian, Tuija Saresma, Tuuli Lähdesmäki, and Maria Ruotsalainen. 2020. “Discursive Constructions of White Nordic Masculinities in Right-wing Populist Media.” Men and Masculinities 23 (3-4): 425–446.

- Paternotte, David, and Roman Kuhar. 2018. “Disentangling and Locating the “Global Right”: Anti-gender Campaigns in Europe.” Politics and Governance 6 (3): 6–19.

- Puar, Jasbir. 2007. Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Sarah De Lange, and Wouter Van der Brug. 2014. “A Populist Zeitgeist? Programmatic Contagion by Populist Parties in Western Europe.” Party Politics 20 (4): 563–575.

- Spierings, Niels. 2020a. “Why Gender and Sexuality are Both Trivial and Pivotal in Populist Radical Right Politics.” In Right-Wing Populism and Gender: European Perspectives and Beyond, edited by Gabriele Dietze, and Julia Roth, 41–58. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Spierings, Niels. 2020b. “Homonationalism and Voting for the Populist Radical Right: Addressing Unanswered Questions by Zooming in on the Dutch Case.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 33 (1): 171–182.

- Spierings, Niels, Marcel Lubbers, and Andrej Zaslove. 2017. “‘Sexually Modern Nativist Voters’: Do They Exist and Do They Vote for the Populist Radical Right?” Gender and Education 29 (2): 216–237.

- Spierings, Niels, and Andrej Zaslove. 2015a. “Conclusion: Dividing the Populist Radical Right Between ‘Liberal Nativism’ and Traditional Conceptions of Gender.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1-2): 163–173.

- Spierings, Niels, and Andrej Zaslove. 2015b. “Gendering the Vote for Populist Radical-Right Parties.” Patterns of Prejudice 49 (1-2): 135–162.

- Verloo, Mieke. 2018. Varieties of Opposition to Gender Equality in Europe. London: Routledge.

- Walby, Sylvia. 2011. The Future of Feminism. London: Polity Press.

- Wissenburg, Marcel. 2001. “Dehierarchization and Sustainable Development in Liberal and Non-liberal Societies.” Global Environmental Politics 1 (2): 95–111.