ABSTRACT

In the autumn of 2018 Greta Thunberg started her school strike. Soon she and the Fridays For Future-movement rose to world-fame, stirring a backlash laying bare the intrinsic climate change denial of Swedish far-right digital media. These outlets had previously been almost silent on climate change, but in 2019, four of the ten most read articles on the site Samhällsnytt were about Thunberg, all of them discrediting the movement and spreading doubt about climate science. Using the conceptualisation of industrial/breadwinner masculinities as developed by Hultman and Pulé [2018. Ecological Masculinities: Theoretical Foundations and Practical Guidance. Routledge Studies in Gender and Environments. New York: Routledge], this article analyses what provoked this reaction. It explores how the hostility to Thunberg was constructed in far-right media discourse in the years 2018–2019, when she became a threat to an imagined industrial, homogenic and patriarchal community. Using conspiracy theories and historical tropes of irrational femininity, the far right was trying to protect the usually hidden environmental privileges, related to unequal carbon emissions and resource use, that Thunberg and her movement made visible.

Introduction

Climate change is affecting all life on earth. In Sweden, most political parties agree that the country, as part of the wealthy, industrialised global north, should be a forerunner in reducing its emissions, but there is a growing opposition to climate change mitigation from far-right nationalism, which has been visible within the main far-right political party the Sweden Democrats. The Swedish far-right media ecosystem hardly wrote about climate change before 2018, but when Greta Thunberg and the climate change justice movement rose to prominence, it became an important issue. By scare-quoting climate, a discourse was created where climate change was perceived as a hoax, and anyone demanding action could be ridiculed (Vowles and Hultman Citation2021). In 2019, four of the ten most read texts on the site Samhällsnytt were about global warming, all of them spreading climate change denial in connection to a story about Thunberg. She was titled ‘alarmist’ and climate change politics were described as an ‘irrational’ and ‘hysterical’ reaction to a scientifically non-existing problem. This can help explain why views about climate change in Sweden are, according to recent reports, becoming nearly as divided as in the US (e.g. Newman et al. Citation2020).

The fossil fuel industry’s attempts to disinform the public about climate change, in contradiction to its own scientific research, stretches back to the 1970s and 1980s (Franta Citation2021). In the early 1990s, it formed a coherent climate change countermovement together with conservative foundations and think tanks, as a reaction to the creation of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and climate scientist James Hansen’s testimony to US congress (e.g. Brulle Citation2014; Dunlap and McCright Citation2011; Oreskes and Conway Citation2011; Stoddard et al. Citation2021). European think tanks have also been active in spreading doubt about climate science (Almiron et al. Citation2020; Busch and Judick Citation2021; Ekberg and Pressfeldt Citationin press), and several of the arguments have been picked up by far-right parties and politicians (e.g. Forchtner Citation2019; A. Malm and The Zetkin Collective Citation2021). In Sweden, there was a consensus about climate change in legacy media up until a short period, 2008–2010, when reporting on climate change was high following the release of Al Gore’s film An Inconvenient Truth in 2006 and connected to the climate summit in Copenhagen 2009. Then, the group the Climate Realists (formerly the Stockholm Initiative), almost exclusively run by older influential men from industry, media, or academia, made a significant impact in spreading literal denial, i.e. to say that climate change is either not happening or not anthropogenic. At once there was a flurry of interest, where these influential individuals were granted media space for articles and statements, but they were later marginalised (Anshelm and Hultman Citation2014). During the mid-2010s, however, several far-right digital alternative media sites grew in influence and here denialism became prominent.Footnote1 A separate media ecosystem emerged that justified itself as being in opposition to a perceived corrupted mainstream media echoing the voice of the elites (Holt Citation2019). The far-right media ecosystem can be characterised by a propaganda feedback loop, where actors police each other regarding ideological content rather than the truthfulness of the news (Benkler, Farris, and Roberts Citation2018). This means that disinformation can easily spread and be amplified.

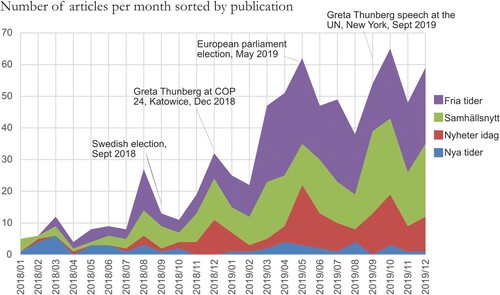

Here we study how four far-right digital news sites reported on climate change and reacted to Greta Thunberg during the years 2018–2019. Fria tider (Free times), Samhällsnytt (Society or Community news), and Nya tider (New times) are clearly within the propaganda feedback loop, while Nyheter idag (News today) sees itself as self-corrective of legacy media but adheres to some journalistic norms. In regard to journalistic practice, it thus takes up a position between the far-right media ecosystem and legacy, or traditional, media. In 2020 the four sites reached between 6 and 12 per cent of Sweden’s online population (Newman et al. Citation2020).

First, we introduce the conceptualisation of industrial/breadwinner masculinities and research showing how anti-environmentalism and anti-feminism overlap. After presenting the four media sites as well as our methodology, we show how Thunberg is portrayed and constructed as a threat to the imagined Swedish community of the far right. We end with a discussion highlighting a few implications of our findings.

Threatened Hegemonic Masculinities

Most of the early scholarly work on gender and climate change identified women, especially in the developing world, as being more severely affected (see special issue of Gender and Development, edited by Masika [Citation2002]). Structural, gendered, and racial inequalities have made women the most vulnerable, and it is them who get hurt the most in natural disasters. Rising temperatures also make caring and provisional work, where women bear an unequal burden, more difficult (Kinnvall and Rydström Citation2019).Footnote2 The structural, gendered, and racial injustices of climate change have been highlighted by Greta Thunberg and her fellow school strikers (Thunberg, Neubauer, and Valenzuela Citation2019).

Following calls from several scholars (e.g. Arora-Jonsson Citation2011; Kaijser and Kronsell Citation2014; MacGregor Citation2010), more work has been done during the last decade looking at gendered climate politics, and unequal power distributions in the global North (Pulé and Hultman, Citation2021). Especially, the value-nexus of right-wing conservatism, anti-environmentalism, and anti-feminism in connection to masculinities has been scrutinised (Agius, Rosamond, and Kinnvall Citation2020; Gaard Citation2015; MacGregor and Seymour Citation2017; McCright and Dunlap Citation2011). Many of the public individuals, most of whom are white and male, who have participated in generating climate controversy, hold strong beliefs in market forces and a mistrust of regulatory government policies (Dunlap and McCright Citation2011; Oreskes and Conway Citation2011). The mere suggestion that we live on a finite planet transformed by carbon pollution challenges the primacy of those who benefit the most from industrialisation and fossil fuel extraction (Anshelm and Hultman Citation2014). This has helped to create the ‘alliance of antagonisms’ (Kaiser and Puschmann Citation2017) between climate change denialism and attitudes of anti-feminism and anti-immigration, which has been seen in survey studies (Jylhä and Hellmer Citation2020; Krange, Kaltenborn, and Hultman Citation2021).

In this study we use industrial/breadwinner masculinities as conceptualised by Hultman and Pulé (Citation2018) in analysing the opposition to Thunberg. These typologies represent a ‘category of men who have long been (and still are) enmeshed with industrial-scale extractive processes and services reliant on energy-intensive, profit-consolidating, ecologically destructive and fossil fuel dependent processes’ (Hultman and Pulé Citation2018, 42). While industrial/breadwinner has been a hegemonic masculinity (Connell Citation1995), Daggett (Citation2018) argues that it now also performs as a reactionary hypermasculinity, as it to a certain degree has lost its hegemonic position.Footnote3 While gender injustices are still prevalent, and the global community has failed to act sufficiently on climate change, feminist and environmental struggle has nonetheless made some progress. This can be seen in that ecomodern masculinities, which acknowledge the crisis but opt for incremental technological solutions, has arguably become hegemonic in large parts of the global North as embodied in Elon Musk and Arnold Schwarzenegger (Hultman Citation2021).

Masculinities are always plural. They are shaped by wider societal practises and economic structures and can be performed simultaneously (Hultman and Pulé Citation2018). In this way they are always temporally and spatially situated in for example a body (both male and non-male), a society, or, as in this study, an order-of-discourse. The plurality of masculinities is also seen in a broad categorisation such as industrial/breadwinner, where the slash marks a class difference. While the industrial masculinities include the owners of the means of production and the corporate CEOs of the fossil fuel companies that continue to heat our planet, not ‘from inner evil … But [because] they are working in an insane elite world that institutionalises competitive, power-oriented masculinity, and they are doing whatever it takes’ (Connell Citation2017, 6), the breadwinners include the workers and former employees in extractive or polluting industries, who often have experienced dwindling economic prospects and social status in an era of neoliberalisation and deindustrialisation (Loomis Citation2017).

What the class difference marks in relation to our material, is that it is reasonable to assume that there is a difference between the ideologues of the sites and at least parts of their readerships. One of the more prominent columnists and Thunberg-critics on both Samhällsnytt and Fria tider is Jan Tullberg, a former assistant professor at the Stockholm School of Economics, thus having a similar background as several members of the Climate Realists. In an article on Fria tider titled: ‘The reason why PC [political correctness] is a totalitarian ideology’ Tullberg (Citation2019a) argues that climate change, together with feminism and immigration, is an essential part of the political correct-ideology which seeks to take away well-earned privileges.Footnote4 ‘The most successful, now-existing societies have been built by dead white men’ Tullberg writes, but even though ‘ … the patriarchy already by its’ own accord has let women through … [it is demanded that] … white men can step back even further.’ With an obvious reference to Thunberg, Tullberg says that children are regarded to be naturally unspoiled, which creates an ‘infantile and emotional debate.’ Tullberg is defending his privileges as a leader in an industrial modern society – perceiving himself as heir to the ‘dead white men’ that built the country, but he is also trying to appeal to the breadwinners in a populist narrative. He constructs political correctness as a totalitarian ideology being forced upon the people. The climate threat, he lets us know, is being pushed by ‘ … international organisations needing international problems … ’ and ‘[w]omen in general do not want more female politicians … , it is the closest affected who wish to get affirmative action quotas’. Here Tullberg portrays political correctness as a creation of an emotional, feminine establishment, while he himself represents the rational voice of the people.

Method and Corpus

Our analysis is based on how four far-right alternative media sites reported on climate change and on Greta Thunberg in the years 2018 and 2019. The four far-right media included in our study are Nyheter idag, Fria tider, Samhällsnytt and Nya tider. The first three are the three biggest, all reaching around 10 per cent of the Swedish online population (See ) (Newman et al. Citation2020). Nya tider has less reach but is included as it also has a print edition, and therefore received €490,000 annually in state press subsidy during the studied period (Mediestödsnämnden Citation2019). All of them, apart from Nya tider, increased the reporting on climate change during the studied period (see ). Nyheter idag stands out as the only medium which has been part of the Swedish self-regulatory media code of ethics. It is run and co-founded by Chang Frick, who used to be a member of the Sweden Democrats. As of June 15, 2020, the site presents itself on its website as ‘resting on a libertarian and liberal-conservative foundation’ (for further information about the other media, see Vowles and Hultman Citation2021).

Table 1. Reach of studied far-right alternative media sites and number of articles in corpus.

Through a search in March 2020 in the Nordic digital press archive Retriever, using the search string ‘klimat* OR uppvärmning OR *greta*’ (‘climate* OR warming OR *greta*’), we received a total of 929 articles from the four sites. After removing 188 articles not related to climate change (mainly about the ‘political climate’ or similar), and 20 articles that either were duplicates, removed, or behind a paywall, the dataset was reduced to 721 articles. If articles behind the wall were available in the print edition of Nya tider, we accessed these through the Royal Library.

We see discourses as ‘being socially constitutive as well as socially conditioned’ (Fairclough and Wodak Citation1997, 258), and as such they are part of political and societal responses to climate change. Discourses are elements of social processes and the order-of-discourse is the semiotic aspect of an established social practice, which is situated in a wider social structure (Fairclough Citation2010). Seeing the far-right alternative media as a social practice, its order-of-discourse includes anti-establishment, anti-feminist and anti-immigration discourses. Climate change has recently been added to the list, and a critical analysis can provide information to why this has been done. Focusing mainly on the hostility to Greta Thunberg, we are striving to get a better understanding of the ideological reasonings and emotional entanglements that shape far-right responses to climate change.

To connect the hostility against Thunberg with previous work on climate change denial, we follow sociologist Stanley Cohen’s (Citation2001) classification scheme of literal, interpretive and implicatory denial (for previous use in climate research, see e.g. Björnberg et al. Citation2017; Norgaard Citation2011). The most relevant categories for this study are literal and implicatory denial, where the former suggests that climate change is a hoax, and the latter is to deny the moral, political, and psychological implications of the knowledge. Cohen stresses that different types of denial often appear simultaneously, as their relationship is ‘ideological, rather than logical’ (Cohen Citation2001, 103).

In doing our analysis the articles have been read at least twice, using Nvivo to openly code e.g. themes, keywords, and tropes. As we are basing our analysis at the order-of-discourse level, we did a qualitative reading of a large number of articles, rather than a line-by-line analysis of a selected few. In our analysis we ask the following questions:

What other discourses are connected to climate?

Anti-immigration, anti-establishment and anti-feminism are prevalent discourses of the far-right (Nygaard Citation2019; Wodak Citation2019). Here we try to see if, and if so how and why, climate change connects to these discourses?

How is Greta Thunberg portrayed?

Here we look for semiotic aspects such as epithets and keywords to see how Thunberg is being perceived. We also analyse strategies for discrediting Thunberg and the climate change justice movement.

The Many Names of Greta Thunberg

‘Climate-Greta’, ‘the so-called climate activist Greta Thunberg’, ‘the climate-alarmist Greta Thunberg’, ‘climate-Messiah’, ‘Media's new favourite alarmist’, ‘doomsday guru’, ‘the Swedish climate icon’, ‘the influence-operation Greta Thunberg’ or the ‘PR-worker Greta Thunberg’. Greta Thunberg is given several different epithets, often in connection with her age, to dismiss her and her movement (the above epithets are respectively, but not exclusively, taken from Kristoffersson [Samhällsnytt] Citation2019a; Fria Tider Citation2019a, Citation2019c, Citation2019d, Citation2019e, Citation2019j; Kristoffersson [Samhällsnytt] Citation2019b, Citation2019c).Footnote5 The term ‘so called’ is widely used together with scare-quoting on Fria tider and Samhällsnytt to demark climate change as a ridiculous issue, without engaging with the science. When entitling Thunberg the ‘so called climate activist’ (e.g. Fria Tider Citation2019h) the signal is that it is impossible to be a climate activist, as climate change is not a problem. When talking about ‘the influence-operation’ or ‘the PR-worker’ Thunberg (Kristoffersson [Samhällsnytt] Citation2019b, Citation2019c), this ties into the conspiracy themes described further below, while epithets such as ‘alarmist’, ‘messiah’, and ‘doomsday prophet’ has a long legacy in contrarian climate change discourse (Coan et al. Citation2021). Satire is used when Thunberg is called ‘media’s new favourite alarmist’ (Fria Tider Citation2019a), trying to ridicule legacy media that are reporting on Thunberg (for satire used against Greta Thunberg, see Konyaeva and Samsonova Citation2021).

Agism has previously been found in Youtube-comments about Thunberg (Park, Liu, and Kaye Citation2021) and is visible also in our data. It is regularly used to discredit her argument, as when Thunberg is coined person of the year 2018 in Nyheter idag (J. Norström Citation2019a), a year when ‘ … the infantilisation of the Swedish public sphere finally was completed. Emotional, irrational and childish arguments filled both columns and debate-programs … and children were regarded as truth-tellers and prophets.’ A similar sentiment is found in Samhällsnytt (Tullberg Citation2019b): ‘ … the infantile is regarded as the most authentic and uncorrupted, we get teenage profits witnessing about the climate’s [sic] approaching judgement day.’

There are slight differences in the discourses between the sites. The most pronounced is how Nya tider engaged in climate change science early on in 2018 but then did not increase its reporting. On the other sites, climate became increasingly important as a reaction to the visibility of the Thunberg-led movement. While Samhällsnytt, Fria tider and Nya tider all literally deny anthropogenic climate change, the discourse on Nyheter idag is one of implicatory denial, where the facts are not denied but the political and moral implications are. This can be seen in that while discrediting Thunberg and arguing against any mitigating action, Nyheter idag usually describe her accurately as a ‘climate activist’. The difference in naming might be explained by how the sites relate to legacy media. While Fria tider, Samhällsnytt and Nya tider are clearly stepping outside established journalistic norms, Nyheter idag has signed up to the self-regulatory code of ethics.

Thunberg as a Mentally ill PR-puppet, Part of Both a Globalist Regime and an Extreme Leftist Sect

Conspiracy theories have been a long-favoured tactic by the organised climate change countermovement, especially arguing that an elitist group is trying to enforce an international, globalist regime (Lewandowsky et al. Citation2015). The far-right media ecosystem, in which we count Fria tider, Samhällsnytt and Nya tider, is characterised by a propaganda feedback loop which allows identity-confirming and ideologically aligned disinformation to spread. This makes it prone to amplify conspiracy theories, and there are several concerning Thunberg. In April 2019, Nya tider posts an English article titled ‘George Soros behind Greta Thunberg’ (Persson Citation2019), which includes a manipulated photo where Soros’ face is pasted on Thunberg’s body. Picking up on a conspiracy getting attention in social media (Dave, Ndulue, and Schwartz-Henderson Citation2020), Nya tider connects Thunberg with Soros through the German climate activist Luisa-Marie Neubauer, as Thunberg and Neubauer appear in several photos together. Neubauer used to be a volunteer for the organisation One campaign, which was backed by Soros’ Open society foundation, a circumstance which according to Nya tider proves that behind ‘every world famous 16-year-old climate activist there is a liberal oligarch and a globalist movement’ (Persson Citation2019). The article is widely shared on social media, 36,000 times according to Nya tider’s own statistics, and it is later picked up by both Samhällsnytt (Westlund Citation2019) and Fria tider (Citation2019g). The story then starts circling international far-right media in connection with the UN climate summit in New York in September 2019, with a manipulated photo of Thunberg and Al Gore made to look like she is standing next to Soros. The anti-Semitic conspiracy theory surrounding Soros can be traced back to the 1990s and has been especially focal in Hungary the last five years (Kalmar Citation2020).

Despite her stark message blaming politicians for failing her generation, Thunberg is often portrayed as being either part of, or manipulated by, the elite. Apart from the Soros conspiracy theory, there is a plot that she is ‘ … an influence operation led by the PR-expert Ingmar Rentzhog, a person connected to several propaganda organs’ (e.g. Kristoffersson [Samhällsnytt] Citation2019a). She is also often portrayed as a mentally ill child that has been manipulated and cynically used by her parents or other adults, as when Samhällsnytt (Putilov Citation2019) reports that several notices of concern have been filed at the social services in Stockholm and quotes one notice as saying ‘ … it’s not good for children with disabilities to be pressured … I am worried that she is being physically or mentally abused and this makes her feel that her childhood is destroyed.’ There are also several articles connecting her with the non-violent, civil disobedience-movement Extinction Rebellion, XR, arguing that she is responsible for criminal activities by an extreme-left climate sect. One example is when Samhällsnytt (Aksoy Citation2019) writes about the founder of the ‘climate-sect’ XR. The article starts: ‘The extreme-left organisation Extinction Rebellion, which Climate-Greta has raised money for, has previously paid activists to disturb the public order – and claimed to be willing to bring down governments with deadly violence.’ In another article, XR-activists are simply referred to as ‘Greta-activists’ (Dagerlind [Samhällsnytt] Citation2019).

In a recent systematic review about conspiracies, Douglas et al. (Citation2019) show that conspiracy-beliefs can in part be linked to perceived existential threats, and that people who feel powerless might turn to conspiracy theories to regain some sense of control in the socio-political realm. The attack on Greta Thunberg by the spreading of conspiracies ties into the anti-establishment and anti-Semitic discourse of the far-right. It is a politically motivated response to the idea of a nation, and its people, being threatened by an elite who wants to create a form of supranational governance. It is a conspiracy that can be appealing to someone who has lost a sense of direction in the world when climate change challenges the industrial/breadwinner legacy.

The anti-establishment rhetoric is reinforced by the way that Twitter and other social media are used in the reporting to provide a reaction to what has been told (cf., Homoláč and Mrázková Citation2021). In connection with a politician or a celebrity speaking out in support of Greta Thunberg, social media is used to portray the voice of the people, perceivably pointing out the madness of the politically correct elite (e.g. Zackrisson [Nyheter idag] Citation2019). This is further seen in discussions about whether media giants such as Facebook and Youtube are responsible for posts on their platforms. When Thunberg argues for Facebook to take responsibility for conspiracies spread about her, the far-right response is that she does not understand freedom of speech (e.g. B. Norström [Nyheter idag] Citation2019). Social media is seen as the protector of free speech, where citizens can get past legacy media’s gatekeepers.Footnote6

Greta Thunberg as a Threat to an Imagined Homogenous, Patriarchal, and Industrially Prosperous Community

Thunberg has been opposed by far-right leaders all over the world. In their study on gendered nationalism, Agius, Rosamond, and Kinnvall (Citation2020, 446) argue that when Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro opposed Greta Thunberg they prioritised ‘the defence and survival of the nation against globalising forces and scientific orthodoxy … in [a] response to an emasculated sense of ontological insecurity.’ To understand this sense of ontological insecurity, we also need to consider the idea of the nation. In his work on nationalism, Benedict Anderson (Citation2016, 6) has defined the nation as an ‘imagined political community’ which is limited and sovereign. It is limited in that no nation is believed to encompass all of humankind, and it is sovereign as nations came into being in the age of the enlightenment, when the rule of dynasty and the supreme god crumbled in the pursuit of scientific rationale and the nation-state became the authority governing public life. This imagined community is filled with deep seated emotions. Core features of the European far right is nativism, that every nation is the home to one ethnic community, and the idea of an endangered nation (Mudde Citation2007; Thorleifsson Citation2020). In an era of neoliberalism and globalisation when the world is changing fast, as for the industrial/breadwinner typologies, nationalism can offer a feeling of stability (Hobsbawm Citation1992, 171–73). The linguist Ruth Wodak (Citation2019, 27) writes that the vision of the far-right is ‘an anachronistic longing for an ethnically homogenous patriarchal society’, and in our corpus there is a clear industrial modern aspect to such patriarchy. The imagined community of the far-right is a homogenous, patriarchal, and industrially prosperous one that needs to be defended at any cost. Where gender equity has dismantled patriarchal authority and immigration has made the community more multi-ethnic, climate change questions the industrial foundation of the modern welfare state. This can be seen in an article in Fria tider (Citation2019i) stating that while ‘China is spending big to become world-leaders in technology, the EU is spending its money on other things: immigration from the third world and climate’ or when Thunberg (Fria tider Citation2019h) is ridiculed for wanted to stop Norwegian oil: ‘The oil has made Norway rich. Extremely rich. But now this might come to an end. At least if you listen to the Swedish climate alarmist Greta Thunberg’. Here it becomes clear that Thunberg and climate policies are perceived to be threatening the fossil fuelled modern economy and thus the wellbeing of the nation, which, as we have seen above, is argued to have been built by white men.

The connected discourses of immigration, gender and climate are spelt out by Ernst Wikmann (Citation2019) on Nya tider, who claims that ‘the three pillars of political correctness […] mass-immigration, feminism and climate alarmism (with accompanying globalism)’ has turned Sweden into a dictatorship that is going under. Or, in the words of Samhällsnytt’s columnist Rolf Malm (Citation2019): ‘No political leader dare to speak frankly about the catastrophically failed integration of people born abroad and the fatal carbon dioxide-fear. The two elephants in the room that more than anything is behind Sweden’s decay.’ A doomsday sect led by a certain 15-year-old ‘ … via her PR-company’ is, according to Malm, the biggest culprit in spreading the carbon dioxide-fear. A similar sentiment is seen in a column titled ‘Conservatism needs to become a counterforce to Greta Thunberg’s global climate sect’ by Ronie Berggren (Citation2019) at Nyheter idag:

If capitalism is what raised humanity from poverty to wealth, it is the democratic nation-states that lifted humanity from tyranny to rule of the people / These things, which took centuries in combination with two world wars to create, are threatened in our times by the global climate sectarianism, which stamps people as climate sinners and older generations as traitors of the descendants.

As a young, female climate activist, the hostility against Thunberg ties into an anti-feminist discourse. She is often portrayed as hysterical, which is exemplified in that all but one of the articles about her in Nyheter idag during the autumn of 2019 are illustrated by screen shots, often in extreme close-up, from her speech at the UN climate summer in September 2019 (e.g. Berggren Citation2019). In these images she is emotional and angry. When Nyheter idag use them in articles that are not related to the speech (e.g. J. Norström Citation2019b), it is used to dismiss Thunberg as irrational. It follows familiar tropes of feminine emotions versus masculine rationality, not least regarding energy and environmental issues. The same argumentation was used against the marine biologist and writer Rachel Carson when she published Silent Spring, warning about indiscriminatory pesticide use in the US in the 1960s.Footnote7 Carson was described as a sensitive and irrational woman, whose love of nature was pitted against a sound, masculine science (Seager Citation2017; Smith Citation2001). What Carson did was to highlight the fragile ecosystems, but her critics saw it as man’s duty to dominate nature, as when an article in Time magazine argued that the idea of ‘balance of nature’ was irrelevant in an industrial society, as ‘ … scientists realistically point out that the balance of nature was upset thousands of years ago when man's invention of weapons made him the king of the beasts’ (cited in Smith Citation2001, 741). Time also claimed that Carson was ‘hysterically emphatic’, a sentiment echoed nearly 60 years later when, to take just one example, Fria tider (Citation2019f) writes that Thunberg has scared several people on social media, not with her message, but through her ‘hysterical behaviour.’ This worldview resonates when Samhällsnytt claims that the Swedish government is in ‘a process of moving from a rational patriarchy to an emotional feminism’ (Tullberg Citation2019b), and when Fria tider reports on a survey about climate anxiety in an article titled: ‘Young women worry about “climate”, young men about immigration’ (Fria Tider Citation2019b). By putting climate into scare quotes, Fria tider dismisses any reason for women to worry about climate, whereas men’s worry about immigration is seen as rational and legitimate.

In a lengthier article published on Nyheter idag, its founder Chang Frick (Citation2019) writes about how he started an electricity supplier company, Svensk Kärnkraft (Swedish Nuclear). ‘Sweden as a nation is being dismantled’, Frick writes, because people in power are listening to younger voices such as Thunberg, instead of ‘natural authorities, not seldom so called “white middle-aged CIS-men”’. Working on national infrastructure projects such as the railway and the energy grid, these men were, in Frick’s words, ‘proud of what they had done and a natural part in a bigger machinery.’ And ‘as a direct consequence of the research and thinking done by the clever men’ there are Swedish diesel engines in ‘ … excavators, wheel loaders and boats all over the world’. Frick is flying the flag of Swedish fossil-based, male coded engineering. Perceiving that the flag is about to be lowered by a feminist climate movement trying to incite a transition to renewables, he launches his nuclear energy company, with the readers of Nyheter idag as the primary customer base.Footnote8 Because of political correctness though, these clever, white, middle-aged CIS-men have been socially marginalised according to Frick, which makes it more difficult to find potential business partners to the electricity supplier company. When contacting a potential partner company, instead of dealing with a clever man, it is a ‘young blond girl with a nose ring’ giving him information, and to her, apparently, nuclear power is not interesting.

Frick is both writing about and addressing the industrial/breadwinners typologies. He salutes their effort in the construction of Sweden and hopes this will resonate among his readership. As a response to the renewable transition the explicit turn to nuclear and the promotion of diesel engines can be understood as an act of refusal. Energy historian Cara Daggett (Citation2018, 41) says: ‘Refusal is active. Angry. It demands struggle. In the case of climate change, by refusing it, one also subscribes to an accelerated investment in petrocultures.’ Frick can be seen to be investing in a masculine, industrial petroculture, especially as climate change is not an argument used to promote Svensk Kärnkraft. Even though the potential of nuclear in a low-carbon energy system is often debated, the only mention of climate on the company website as of 16 June 2020, is in the slogan ‘0 percent climate anxiety, 100 percent nuclear’. Considering the far-right discourse ridiculing climate anxiety seen above, the slogan is a provocation against the climate movement rather than a factual statement about carbon emissions from nuclear energy. The company argues for nuclear power as a ‘stable and reliable’ source of energy that will allow ‘industries to keep growing and create jobs’. Nuclear power will save the industrial nation, the one perceived to be dismantled when society is listening more to Greta Thunberg than clever, elderly men.

Discussion

It was relatively late in the autumn of 2018 that the Swedish far-right alternative media sites started writing about climate and Greta Thunberg. While Thunberg’s school strike was widely reported in legacy media already in august 2018 and leading up to the Swedish election, it was only in connection to the climate summit in Katowice that the far-right started paying attention (see ). We can see two reasons for this. The first and main one is that the climate reporting on the far-right is reactionary. A topic so prominent in legacy media demanded a response, and far-right alternative media went from being silent on the topic, to spreading denial and being hostile to Thunberg. Especially when she gained international fame.

The second is that far-right media needed a way to discredit the movement. It was only when the conspiracy theories regarding Thunberg were created and started circling on social media that far-right media had a story fitting their worldview. A girl protesting politicians’ inaction on climate change sitting alone outside the Swedish parliament was not a topic that could engage their readers, but a story about a girl being manipulated by the establishment, including her, in Sweden, well-known parents, was. Thus, this became their response – by connecting Thunberg to a global conspiracy and portraying her and the wider climate movement as hysterical, they could go on the attack.

Turning to our research questions we see that:

Climate change is connected to the anti-establishment discourse in many of the articles in our dataset. Before Greta Thunberg started her school strike, climate as an issue is mentioned mainly when it can be directly tied to immigration (e.g. Fria Tider Citation2018), but later it becomes a prominent topic on its own. In the longing for an imagined homogenous, patriarchal, and industrial nation, climate change becomes a threat alongside immigration and feminism.

The far-right media deals with this threat by denying it. Either literally as in the case of Fria tider, Samhällsnytt, and Nya tider, or implicatively in the case of Nyheter idag. Through conspiracy theories and familiar tropes of female hysteria versus masculine rationality, Thunberg is discredited as emotionally unstable.

The Swedish far-right alternative media hardly wrote about climate change before 2018, and later research show that the topic dropped in importance in 2020 during the Covid-pandemic (Arnell and Blomberg Citation2021). What our study suggests however, is that it is an issue that cuts to the heart of the envisioned society of the far right, and which threatens the environmental privileges that comes from belonging to industrial/breadwinner typologies. This makes the reality of climate change difficult to accept for parts of the far right, but they can remain silent if the topic is not widely discussed in legacy media. When there is a chance of real mitigating action, however, and Greta Thunberg and the climate change justice-movement put pressure on governments all over the world to reduce emissions, the far-right media needs to act. Indeed, a parallel can be drawn to how the climate change-countermovement in the US – from which the far right gets several arguments – took shape in the early 1990s as a response to the formation of the IPCC and James Hansen’s testimony in US congress. Then the fossil fuel industry, despite having their own climate change research, started spreading denial as they deemed climate regulation as a threat to their business model. Now Swedish far-right digital media are spreading denial as climate change policies are seen as a threat to their imagined community. This is also a lesson for the future, if ever it seems like literal climate denialism has disappeared, one reason might be a lack of any real mitigating action.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper have been presented at the STS-seminar at Chalmers; HAS at the Department of Media, Journalism and Communication at Gothenburg University; and the Green Room-seminar at Linköping University. The authors thank the participants and two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kjell Vowles

Kjell Vowles is a PhD-candidate at the division of STS at Chalmers University of Technology mainly researching climate change denial, the far-right and nationalism. Martin Hultman is an associate professor at the same division and is widely published in energy, climate, and environmental issues. Especially notable are the articles ‘The Making of an Environmental Hero: A History of Ecomodern Masculinity, Fuel Cells and Arnold Schwarzenegger’ and ‘A green fatwā? Climate change as a threat to the masculinity of industrial modernity’ and the books Discourses of Global Climate Change and Ecological Masculinities. Together Vowles and Hultman has previously published the article ‘Scare-quoting climate: The rapid rise of climate denial in the Swedish far right media ecosystem’ (2021), in the Nordic Journal of Media Studies, volume 3.

Martin Hultman

Martin Hultman is an Associate professor in Science, Technology and Environmental Studies at the Department of Technology Management and Economics at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Notes

1 The term ‘alternative media’ has traditionally been used for politically left leaning media. Holt, Figenschou, and Frischlich (Citation2019, 861), however, argue that an umbrella definition of alternative media helps connect present research with previous literature. The essence is that alternative media perceive itself in opposition to a hegemonic media discourse ‘corrupted by, dependent on and uncritical of the establishment’. An umbrella definition does not claim that all alternative media are alike. Nygaard (Citation2019) distinguish ‘immigration-critical alternative media’ but this term does not capture the ideological positions related to climate change. Ylä-Anttila, Bauvois, and Pyrhönen (Citation2019) uses the term ‘counter-media’ which highlights the oppositional character but misses the ideological dimension. Hence we use ‘far-right alternative media’, and, for short and interchangeably, ‘far-right media’.

2 In certain contexts, though, such as in the case of Australian bushfires, death-tolls are higher among men due to rural masculinities proposing that they should fight fires and defend the home, when women and children evacuate (Tyler and Fairbrother Citation2013).

3 Daggett (Citation2018) has developed the concept ‘petro-masculinity’, which has considerable overlap with industrial/breadwinner masculinities.

4 All translations from Swedish to English done by first author.

5 The name of the site is put in square brackets when this is not apparent from the text or the reference.

6 In other cases the far-right discourse has shifted in relation to tech-giants such as Facebook and Twitter, and other platforms which claim not to moderate user content have become popular.

7 In Sweden, the leading environmental and energy politicians Birgitta Hambraeus and Birgitta Dahl were subjected to similar abuse in the 1980s (Hultman, Kall, and Anshelm Citation2021).

8 Specifically, it could be argued that Frick’s nuclear energy company is a reaction to the solar energy company started by the feminist and socialist newspaper ETC’s founder Johan Ehrenberg (Wåg Citation2019).

References

- Agius, Christine, Annika Bergman Rosamond, and Catarina Kinnvall. 2020. “Populism, Ontological Insecurity and Gendered Nationalism: Masculinity, Climate Denial and Covid-19.” Politics, Religion & Ideology 21 (4): 20. doi:10.1080/21567689.2020.1851871.

- Aksoy, Mira. 2019. “Extinction Rebellions grundare bagatelliserar Förintelsen: ‘Bara en vanlig händelse’.” Samhällsnytt, Novemeber 21. https://samnytt.se/extinction-rebellions-grundare-bagatelliserar-forintelsen-bara-en-normal-handelse/.

- Almiron, Núria, Maxwell Boykoff, Marta Narberhaus, and Francisco Heras. 2020. “Dominant Counter-Frames in Influential Climate Contrarian European Think Tanks.” Climatic Change 162 (4): 2003–2020. doi:10.1007/s10584-020-02820-4.

- Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 2016. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised ed. London: Verso.

- Anshelm, Jonas, and Martin Hultman. 2014. “A Green Fatwā? Climate Change as a Threat to the Masculinity of Industrial Modernity.” NORMA 9 (2): 84–96. doi:10.1080/18902138.2014.908627.

- Arnell, Nils, and Johanna Blomberg. 2021. “Så Kallade ‘Klimatförändringar’.” Bachelor thesis, Gothenburg University. https://expo.jmg.gu.se/wp-content/uploads/KH20-2.pdf.

- Arora-Jonsson, Seema. 2011. “Virtue and Vulnerability: Discourses on Women, Gender and Climate Change.” Global Environmental Change 21 (2): 744–751. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.005.

- Benkler, Yochai, Robert Farris, and Hal Roberts. 2018. Network Propaganda. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190923624.001.0001.

- Berggren, Ronie. 2019. “Ronie Berggren: Konservatismen behöver bli motkraft till Greta Thunbergs globala klimatsekt.” Nyheter idag, September 24. https://nyheteridag.se/ronie-berggren-konservatismen-behover-bli-motkraft-till-greta-thunbergs-globala-klimatsekt/.

- Björnberg, Karin Edvardsson, Mikael Karlsson, Michael Gilek, and Sven Ove Hansson. 2017. “Climate and Environmental Science Denial: A Review of the Scientific Literature Published in 1990–2015.” Journal of Cleaner Production 167 (November): 229–241. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.066.

- Brulle, Robert J. 2014. “Institutionalizing Delay: Foundation Funding and the Creation of U.S. Climate Change Counter-Movement Organizations.” Climatic Change 122 (4): 681–694. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-1018-7.

- Busch, Timo, and Lena Judick. 2021. “Climate Change—That Is Not Real! A Comparative Analysis of Climate-Sceptic Think Tanks in the USA and Germany.” Climatic Change 164 (1–2): 18. doi:10.1007/s10584-021-02962-z.

- Coan, Travis G., Constantine Boussalis, John Cook, and Mirjam O. Nanko. 2021. “Computer-Assisted Classification of Contrarian Claims About Climate Change.” Scientific Reports 11 (1): 22320. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-01714-4.

- Cohen, Stanley. 2001. States of Denial: Knowing About Atrocities and Suffering. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Connell, Raewyn. 1995. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Connell, Raewyn. 2017. “Masculinities in the Sociocene.” In RCC Perspectives: Men and Nature: Hegemonic Masculinities and Environmental Change, edited by Sherilyn MacGregor, and Nicole Seymour, 5–8. Munich: Rachel Carson Center.

- Dagerlind, Mats. 2019. “VIDEO: Här slås Greta-aktivister ner av morgonpendlare.” Samhällsnytt, October 17. https://samnytt.se/video-har-slas-greta-aktivister-ner-av-morgonpendlare/.

- Daggett, Cara. 2018. “Petro-Masculinity: Fossil Fuels and Authoritarian Desire.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 47 (1): 25–44. doi:10.1177/0305829818775817.

- Dave, Aashka, Emily Boardman Ndulue, and Laura Schwartz-Henderson. 2020. “Targeting Greta Thunberg: A Case Study in Online Mis/Disinformation.” Policy paper. Washington, DC: German Marshall Fund of the United States.

- Douglas, Karen M., Joseph E. Uscinski, Robbie M. Sutton, Aleksandra Cichocka, Turkay Nefes, Chee Siang Ang, and Farzin Deravi. 2019. “Understanding Conspiracy Theories.” Political Psychology 40 (S1): 3–35. doi:10.1111/pops.12568.

- Dunlap, Riley E., and Aaron M. McCright. 2011. “Organized Climate Change Denial.” In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society, edited by John S. Dryzek, Richard B. Norgaard, and David Schlossberg, 144–160. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ekberg, Kristoffer, and Victor Pressfeldt. In press. “A Road to Denial – Climate Change and Neoliberal Thought in Sweden, 1988–2000.” Contemporary European History.

- Fairclough, Norman. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Fairclough, Norman, and Ruth Wodak. 1997. “Critical Discourse Analysis.” In Discourse as Social Interaction, edited by Teun A. van Dijk, Reprint, 258–284. London: Sage.

- Forchtner, Bernhard, ed. 2019. The Far Right and the Environment: Politics, Discourse and Communication. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Franta, Benjamin. 2021. “Early Oil Industry Disinformation on Global Warming.” Environmental Politics January: 1–6. doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1863703.

- Fria Tider. 2018. “Grön Ungdom spår ENORM invandring i framtiden – kräver mer ‘medmänsklighet’ av svenskarna.” Fria Tider, March 10. http://www.friatider.se/gr-n-ungdom-sp-r-enorm-invandring-i-framtiden-kr-ver-mer-medm-nsklighet-av-svenskarna.

- Fria Tider. 2019a. “Greta Thunberg vill att alla ska ‘känna panik’ över klimatet”. Fria Tider, January 26. http://www.friatider.se/greta-thunberg-vill-att-alla-ska-k-nna-panik-ver-klimatet.

- Fria Tider. 2019b. “Unga kvinnor oroar sig för ‘klimatet’, unga män för invandringen.” Fria Tider, March 14. http://www.friatider.se/unga-kvinnor-oroar-sig-f-r-klimatet-unga-m-n-f-r-invandringen.

- Fria Tider. 2019c. “Greta får personligt möte – med påven.” Fria Tider, April 15. http://www.friatider.se/greta-thunberg-f-r-personligt-m-te-med-p-ven.

- Fria Tider. 2019d. “Gretas nya smeknamn: ‘Domedagsguru’.” Fria Tider, July 23. https://www.friatider.se/gretas-nya-smeknamn-domedagsguru.

- Fria Tider. 2019e. “Klimat-Greta sparkar ut journalister efter bråk.” Fria Tider, August 13. https://www.friatider.se/klimat-greta-sparkar-ut-journalister-efter-br-k.

- Fria Tider. 2019f. “Trumps svar till Greta: ‘En glad ung flicka’.” Fria Tider, September 24. https://www.friatider.se/trumps-svar-till-greta-en-glad-ung-flicka.

- Fria Tider. 2019g. “Greta skriver i Soros-tidning: ‘Rasismen’ måste bekämpas.” Fria Tider, December 3. https://www.friatider.se/greta-skriver-i-soros-tidning-rasismen-m-ste-bek-mpas.

- Fria Tider. 2019h. “Greta kräver att Norge slopar oljeproduktion.” Fria Tider, December 10. https://www.friatider.se/greta-kr-ver-att-norge-slopar-oljeproduktion.

- Fria Tider. 2019i. “EU satsar tusen miljarder på ‘klimatet’.” Fria Tider, December 12. https://www.friatider.se/eu-satsar-tusen-miljarder-p-klimatet.

- Fria Tider. 2019j. “Greta tillbaka vid riksdagen: ‘Det är kris’.” Fria Tider, December 20. https://www.friatider.se/greta-tillbaka-vid-riksdagen-det-r-kris.

- Frick, Chang. 2019. “Tänk om tjejerna med näsring inte kan ladda mobilen?” Nyheter idag, June 5. https://nyheteridag.se/tank-om-tjejerna-med-nasring-inte-kan-ladda-mobilen/.

- Gaard, Greta. 2015. “Ecofeminism and Climate Change.” Women’s Studies International Forum 49 (March): 20–33. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2015.02.004.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. 1992. Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Holt, Kristoffer. 2019. Right-Wing Alternative Media. 1st ed. London; New York: Routledge.

- Holt, Kristoffer, Tine Ustad Figenschou, and Lena Frischlich. 2019. “Key Dimensions of Alternative News Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (7): 860–869. doi:10.1080/21670811.2019.1625715.

- Homoláč, Jiří, and Kamila Mrázková. 2021. “A Skirmish on the Czech Political Scene: The Glocalization of Greta Thunberg’s UN Climate Action Summit Speech in the Czech Media.” Discourse, Context & Media 44 (December): 100547. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100547.

- Hultman, M. 2021. “The Process of Ecologisation: Is Schwarzenegger Back to Teach Us Something New?” In Men, Masculinities, and Earth, edited by P. M. Pulé, and M. Hultman, 169–181. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hultman, Martin, Ann-Sofie Kall, and Jonas Anshelm. 2021. Att ställa frågan. Att våga omställning. Birgitta Hambraeus och Birgitta Dahl i den svenska energi- och miljöpolitiken 1971–1991. Lund: Arkiv förlag.

- Hultman, Martin, and Paul M. Pulé. 2018. Ecological Masculinities: Theoretical Foundations and Practical Guidance. Routledge Studies in Gender and Environments. New York: Routledge.

- Jylhä, Kirsti M., and Kahl Hellmer. 2020. “Right-Wing Populism and Climate Change Denial: The Roles of Exclusionary and Anti-Egalitarian Preferences, Conservative Ideology, and Antiestablishment Attitudes.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy April: 1–21. doi:10.1111/asap.12203.

- Kaijser, Anna, and Annica Kronsell. 2014. “Climate Change Through the Lens of Intersectionality.” Environmental Politics 23 (3): 417–433. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.835203.

- Kaiser, Jonas, and Cornelius Puschmann. 2017. “Alliance of Antagonism: Counterpublics and Polarization in Online Climate Change Communication.” Communication and the Public 2 (4): 371–387. doi:10.1177/2057047317732350.

- Kalmar, Ivan. 2020. “Islamophobia and Anti-Antisemitism: The Case of Hungary and the ‘Soros Plot’.” Patterns of Prejudice, April, 1–17. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2019.1705014.

- Kinnvall, Catarina, and Helle Rydström, eds. 2019. Climate Hazards, Disasters, and Gender Ramifications. London: Routledge.

- Konyaeva, Yulia Mikhailovna, and Anastasiya Aleksandrovna Samsonova. 2021. “Sarcastic Evaluation in Mass Media as a Way of Discrediting a Person: Greta Thunberg Case.” The European Journal of Humour Research 9 (1): 74–86. doi:10.7592/EJHR2021.9.1.Konyaeva.

- Krange, Olve, Bjørn P. Kaltenborn, and Martin Hultman. 2021. “‘Don’t Confuse me with Facts’ — how Right Wing Populism Affects Trust in Agencies Advocating Anthropogenic Climate Change as a Reality.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00930-7.

- Kristoffersson, Simon. 2019a. “Malena Ernman erkänner: professionell lobbyist bakom Klimat-Gretas strejk.” Samhällsnytt, January 7. https://samnytt.se/malena-ernman-erkanner-professionell-lobbyist-bakom-klimat-gretas-strejk/.

- Kristoffersson, Simon. 2019b. “Tusentals skolelever med klimatångest skolkade med Klimat-Greta.” Samhällsnytt, March 15. https://samnytt.se/tusentals-skolelever-med-klimatangest-skolkade-med-klimat-greta/.

- Kristoffersson, Simon. 2019c. “Kommun indoktrinerar småbarn att hata ‘korkade vuxna’ som kritiserar Greta.” Samhällsnytt, November 20. https://samnytt.se/kommun-indoktrinerar-smabarn-att-hata-korkade-vuxna-som-kritiserar-greta/.

- Lewandowsky, S., J. Cook, K. Oberauer, S. Brophy, E. A. Lloyd, and M. Marriott. 2015. “Recurrent Fury: Conspiratorial Discourse in the Blogosphere Triggered by Research on the Role of Conspiracist Ideation in Climate Denial.” Journal of Social and Political Psychology 3 (1): 142–178. doi:10.5964/jspp.v3i1.443.

- Loomis, Erik. 2017. “Masculinity, Work, and the Industrial Forest in the US Pacific Northwest – Work and Manhood.” Application/pdf. In Men and Nature: Hegemonic Masculinities and Environmental Change, edited by Sherilyn MacGregor, and Nicole Seymour, 37–43. Munich: Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/7977/.

- MacGregor, Sherilyn. 2010. “‘Gender and Climate Change’: From Impacts to Discourses.” Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 6 (2): 223–238. doi:10.1080/19480881.2010.536669.

- MacGregor, Sherilyn, and Nicole Seymour, eds. 2017. Men and Nature: Hegemonic Masculinities and Environmental Change. Application/pdf. Munich: Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/7977/.

- Malm, Rolf. 2019. “Rensa ut och börja om!” Samhällsnytt, February 20. https://samnytt.se/rensa-ut-och-borja-om/.

- Malm, Andreas, and The Zetkin Collective. 2021. White Skin, Black Fuel: On the Danger of Fossil Fascism. London: Verso.

- Masika, Rachel. 2002. “Editorial.” Gender & Development 10 (2): 2–9. doi:10.1080/13552070215910.

- McCright, Aaron M., and Riley E. Dunlap. 2011. “Cool Dudes: The Denial of Climate Change among Conservative White Males in the United States.” Global Environmental Change 21 (4): 1163–1172. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003.

- Mediestödsnämnden. 2019. Beviljade driftsstöd 2019. https://www.mprt.se/globalassets/dokument/stod-till-medier/beviljade-stod/driftsstod/beviljat-driftsstod-2019.pdf.

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nässén, Nessica, and Komalsingh Rambaree. 2021. “Greta Thunberg and the Generation of Moral Authority: A Systematic Literature Review on the Characteristics of Thunberg’s Leadership.” Sustainability 13 (20): 11326. doi:10.3390/su132011326.

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Andi Simge, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. “Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020.” Digital News Report. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Norgaard, Kari Marie. 2011. Living in Denial. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Norström, Björn. 2019. “Björn Norström: Utbilda dig om amerikansk yttrandefrihet, Greta Thunberg.” Nyheter idag, October 28. https://nyheteridag.se/bjorn-norstrom-utbilda-dig-om-amerikansk-yttrandefrihet-greta-thunberg/.

- Norström, Jonathan. 2019a. “Fem snabba frågor om 2018 – Ann Heberlein: ‘Årets person tveklöst Greta Thunberg’.” Nyheter Idag, January 2. https://nyheteridag.se/fem-snabba-fragor-om-2018-ann-heberlein-arets-person-tveklost-greta-thunberg/.

- Norström, Jonathan. 2019b. “SVT-program anmäls – gick på klimatstrejk med Greta Thunberg”. Nyheter idag, November 28. https://nyheteridag.se/svt-program-anmals-gick-pa-klimatstrejk-med-greta-thunberg/.

- Nygaard, Silje. 2019. “The Appearance of Objectivity: How Immigration-Critical Alternative Media Report the News.” Journalism Practice 13 (10): 1147–1163. doi:10.1080/17512786.2019.1577697.

- Oreskes, Naomi, and Eric Conway. 2011. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

- Park, Chang Sup, Qian Liu, and Barbara K. Kaye. 2021. “Analysis of Ageism, Sexism, and Ableism in User Comments on YouTube Videos About Climate Activist Greta Thunberg.” Social Media + Society 7 (3): 205630512110360. doi:10.1177/20563051211036059.

- Persson, Jonas. 2019. “George Soros behind Greta Thunberg.” Nya Tider, April 24. https://www.nyatider.nu/the-global-network-behind-greta-thunberg/.

- Pulé, P. M., and M. Hultman, eds. 2021. Men, Masculinities, and Earth Contending with the (m)Anthropocene. London: Palgrave.

- Putilov, Egor. 2019. “BEKRÄFTAT: Flera orosanmälningar om Greta handläggs av socialtjänsten.” Samhällsnytt, September 25. https://samnytt.se/bekraftat-flera-orosanmalningar-om-greta-handlaggs-av-socialtjansten/.

- Seager, Joni. 2017. “Rachel Carson Was Right – Then, and Now.” In Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment, edited by Sherilyn MacGregor, 27–42. Abingdon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315886572-2.

- Smith, Michael B. 2001. ““Silence, Miss Carson!” Science, Gender, and the Reception of “Silent Spring”.” Feminist Studies 27 (3): 733. doi:10.2307/3178817.

- Stoddard, Isak, Kevin Anderson, Stuart Capstick, Wim Carton, Joanna Depledge, Keri Facer, Clair Gough, et al. 2021. “Three Decades of Climate Mitigation: Why Haven’t We Bent the Global Emissions Curve?” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46 (1): 653–689. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011104.

- Thorleifsson, Cathrine. 2020. Nationalist Responses to the Crises in Europe: Old and New Hatreds. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Thunberg, Greta, Luisa Neubauer, and Angela Valenzuela. 2019. “Why We Strike Again.” Project Syndicate, November 29. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/climate-strikes-un-conference-madrid-by-greta-thunberg-et-al-2019-11.

- Tullberg, Jan. 2019a. “Därför är PK en totalitär ideologi.” Fria Tider, March 3. http://www.friatider.se/d-rf-r-r-pk-en-totalit-r-ideologi.

- Tullberg, Jan. 2019b. “En destruktiv kulturrevolutiom.” Samhällsnytt, August 16. https://samnytt.se/en-destruktiv-kulturrevolution/.

- Tyler, Meagan, and Peter Fairbrother. 2013. “Bushfires Are ‘Men’s Business’: The Importance of Gender and Rural Hegemonic Masculinity.” Journal of Rural Studies 30 (April): 110–119. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2013.01.002.

- Vowles, Kjell, and Martin Hultman. 2021. “Scare-Quoting Climate: The Rapid Rise of Climate Denial in the Swedish Far-Right Media Ecosystem.” Nordic Journal of Media Studies 3 (1): 79–95. doi:10.2478/njms-2021-0005.

- Wåg, Mathias. 2019. “You Are the Ecofascists!.” Presentation presented at Political Ecologies of The Far Right, Lund, November 15–17.

- Westlund, Hans. 2019. “Klimat-Greta flydde från intervju med kritiska frågor.” Samhällsnytt, October 18. https://samnytt.se/klimat-greta-flydde-fran-intervju-med-kritiska-fragor/.

- Wikmann, Ernst. 2019. “Arnstberg: Sverige är inte längre en demokrati.” Nya Tider, November 7. https://www.nyatider.nu/arnstberg-sverige-ar-inte-langre-en-demokrati/.

- Wodak, Ruth. 2019. “The Trajectory of Far-Right Populism – A Discourse-Analytical Perspective.” In The Far Right and the Environment: Politics, Discourse and Communication, edited by Bernhard Forchtner, 21–37. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ylä-Anttila, Tuukka, Gwenaëlle Bauvois, and Niko Pyrhönen. 2019. “Politicization of Migration in the Countermedia Style: A Computational and Qualitative Analysis of Populist Discourse.” Discourse, Context & Media 32 (December): 100326. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100326.

- Zackrisson, Pelle. 2019. “Frida Boisen: ‘Greta Thunberg är på väg att bli vår världs frälsare’.” Nyheter idag, March 16. https://nyheteridag.se/frida-boisen-greta-thunberg-ar-pa-vag-att-bli-var-varlds-fralsare/.