ABSTRACT

How to imagine other kinds of world-making when there is a loss of species; livelihoods are threatened, and lives are on the line? Stoddard et al. (2021) note that there is a lack of social imaginaries. Critical, creative practices act in a tradition of responding to complex questions by turning them into embodied inquiries and opportunities to imagine how things could be otherwise (Mareis and Paim 2021; DiSalvo 2022). The project Un/Making Pollination is a designerly response to the twofolded lack of pollinators and imagination. It is an exploration on how to approach more liveable feminist futures by relationship building across species, with a focus on plant-pollinator-human relationships. The authors give a critical account of choices in the creation of a series of posters and hand pollination tools as feminist methods of opening ecosocial imaginaries. These feminist ways of knowing and worlding are also methods of inquiring, making, giving form, using senses, connecting temporalities, spaces and bodies, getting attracted, lured in and touched by the making and unmaking of biodiversity. We articulate and perform references of feminist methods for combining knowledge production with everyday life that can contribute to imagining otherworlds.

Introduction

There is currently a lack of biodiversity and, more particularly, a loss of pollinators (IPBES Citation2019). This article takes as its starting point that the dominant stories of how to tackle the loss of pollinators are thin. Thin stories propose solutions within a framework that does not sufficiently consider the current complexities and uncertainties (see for example Jönsson, Lindström, and Ståhl Citation2021). There is thus not only a lack of pollinators but also a lack of imaginaries of how to handle the current emergencies.

To set imaginaries in motion of how things could be otherwise, we draw from a tradition of using creative practices of making complex issues tangible and experientially available. DiSalvo (Citation2022) for example writes that across different design approaches there is a ‘shared belief that the creative capacities of design can enable us to imagine and act in the world differently and […] in varied ways, they are all experimental practices: they all involve forms of inquiry through making and use’ (6). The authors of this article have gathered in The Un/Making Studio in Malmö, southern Sweden to articulate a designerly response to the two-folded lack of pollinators and imagination, by inquiring, making, giving form, and using senses across different bodies, medium, place and time to imagine other worlds and actions. Based on the artistic work of making posters of human–plant–pollinator relationships and a place-based workshop for making hand-pollination tools, this article suggests feminist methods of enriching current ecosocial sensibilities and contributing to making liveable futures. A set of posters and a workshop have been developed to thicken the stories that can help the audience and participants become better at noticing holistic and interrelated relationships. A focal point of this article is also to highlight the labour of the artistic work, not as individual pieces but as a particular form for ecosocial care work of weaving concepts, proposals and practices together. To thicken the stories, we deem it important to make the process and design decisions visible as references for others to produce more just forms of knowledge and as a way to acknowledge those who helped us find our way artistically, methodologically and conceptually ().

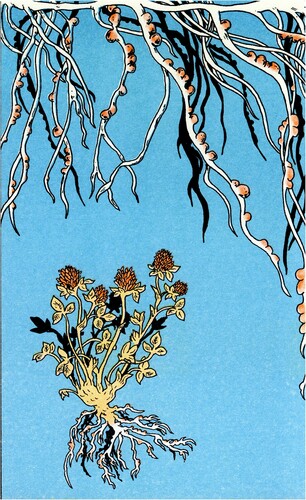

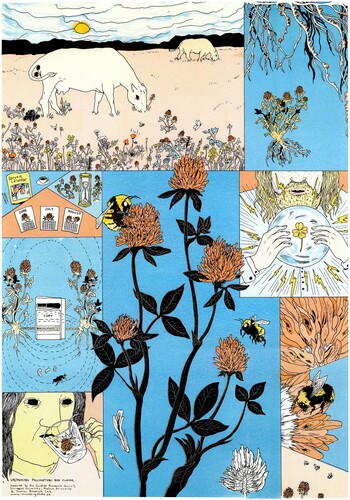

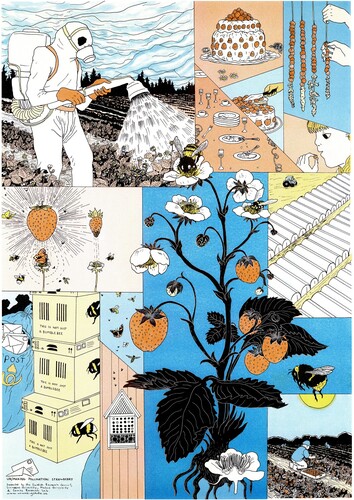

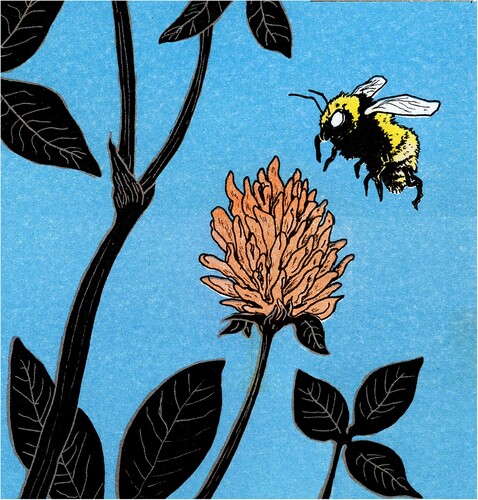

Figure 1. Plant–pollinator relationships at stake, or in some way out of sync, in Southern Sweden, Northern Europe. A2 size riso printed posters, drawn with thin, clear ink lines and coloured in bright shades of orange, yellow, aqua and camel brown. Large portraits of the plants in bloom with visiting insect pollinators take a central place in the image, surrounded by a frame of smaller thickener panels – images that expand the story – different facets of a prism presenting these relationships. Red Clover is more or less dependent on one particular pollinator – the great yellow bumblebee (klöverhumla). This is because the great yellow bumblebee has a tongue that is long enough to reach all the way down into the floral barrel of the clover. The great yellow bumblebee is, however, listed as a threatened species in Sweden, partly due to the ways that landscapes are farmed. Copyright Saskia Gullstrand.

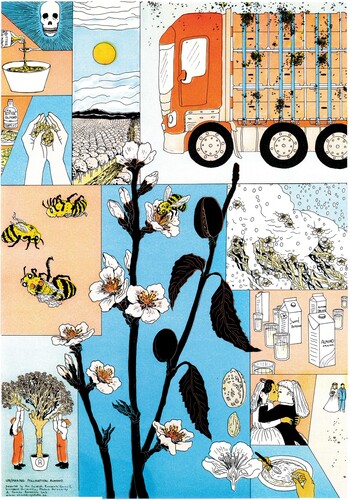

Figure 2. Plant–pollinator relationships at stake, or in some way out of sync, in Southern Sweden, Northern Europe. A2 size riso printed posters, drawn with thin, clear ink lines and coloured in bright shades of orange, yellow, aqua and camel brown. Large portraits of the plants in bloom with visiting insect pollinators take a central place in the image, surrounded by a frame of smaller thickener panels – images that expand the story – different facets of a prism presenting these relationships. Almond trees, on the other hand, are less common in Sweden. Most of the almonds and the almond milk that you can buy in Sweden come from large plantations in California, where the almond trees are pollinated by bees being transported on trucks. Partly due to climate change and bioengineered varieties, there are, however, also ongoing attempts to grow and farm almonds in Southern Sweden. Copyright Saskia Gullstrand.

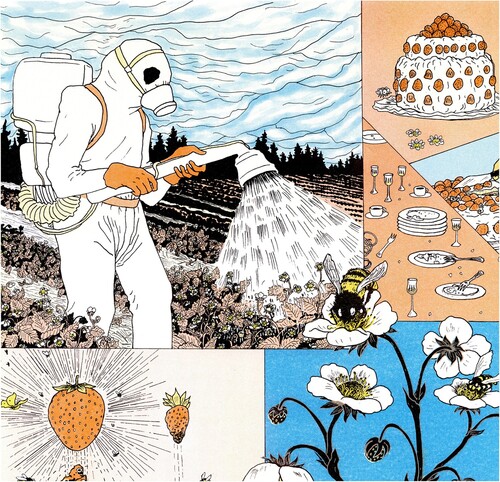

Figure 3. Plant–pollinator relationships at stake, or in some way out of sync, in Southern Sweden, Northern Europe. A2 size riso printed posters, drawn with thin, clear ink lines and coloured in bright shades of orange, yellow, aqua and camel brown. Large portraits of the plants in bloom with visiting insect pollinators take a central place in the image, surrounded by a frame of smaller thickener panels – images that expand the story – different facets of a prism presenting these relationships. Strawberries used to be accessible in Sweden only during the summer. They are a central dish at midsummer celebrations. Nowadays, you can buy strawberries all year. They are often farmed in large greenhouses. To secure a full harvest, these plants are often pollinated by bumblebees that are ordered and delivered by mail. Copyright Saskia Gullstrand.

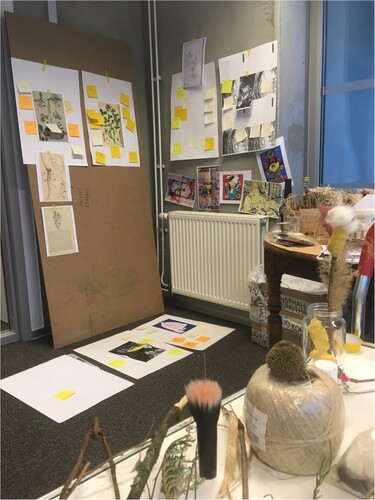

Figure 4. The poster with red clover and the making of hand pollination tools on the dock. Photo by Li Jönsson.

Figure 5. The poster with red clover and the making of hand pollination tools on the dock. Photo by Åsa Ståhl.

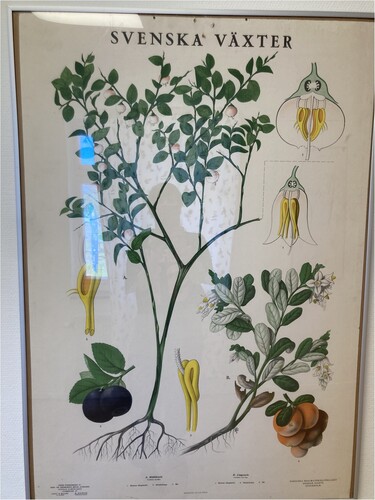

Figure 7. Example of a school poster photographed in a contemporary Swedish school, showing blueberries and lingonberries. (Photo credit: Åsa Ståhl).

Figure 8. Work material in the studio including image references such as those of Cristina Daura and Fien Jorissen. (Photo credit: Åsa Ståhl).

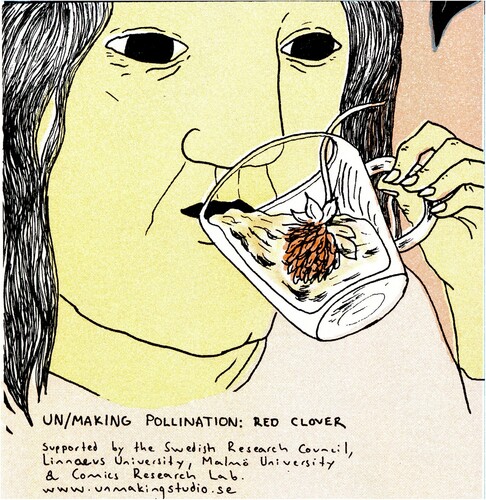

Figure 9. Some of the thickening panels. Red clover to be drunk for cooling down. Copyright: Saskia Gullstrand.

Figure 10. Some of the thickening panels. Great yellow bumblebee that is an expert pollinator for red clover. Copyright: Saskia Gullstrand.

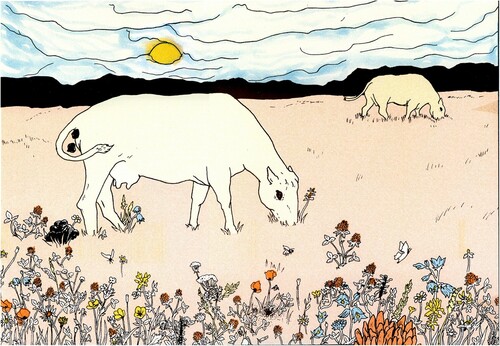

Figure 13. Two cows are grazing in a large meadow, one of them releasing a dump of thick, wet cow droppings in the grass. In the foreground, you see an abundance of wildflowers and several insects flying around. If you look closely, you’ll see a hole in the ground by the red poppies in the middle of the image – this is the entrance to a great yellow bumblebee nest. There are black silhouettes of mountains and a large yellow sun peeking out through thick clouds in the background. There are no humans in the picture, making it at first glance possible to read as an idyllic depiction of a relationship between animals and plants uncompromised by humans – an ideal state of things, where the great yellow bumblebee can thrive and continue to be involved in sexually reproducing with the red clover flowers, and destructive humans are removed. However, despite the absence of humans in this depiction of the grazing cows and the meadow that they sustain, there are humans involved. This panel shows a type of landscape that has been formed together with human agricultural practices, with small cow farms, which created adequate living conditions for the great yellow bumblebee. The image stretches through time. Are we looking at a scene from the seventeenth century or a more contemporary one? Is it a speculation on liveable futures? For whom? This type of human–pollinator–plant relationship does (still) exist in some places of Sweden (e.g. nature reserves where cows graze to keep meadows open), and it was until not very long ago a common sight. The image is thick because it holds several temporalities. It echoes of loss but also hope for the future through the suggestion that humans have managed in the past to have liveable and supportive relationships with these insect pollinators and plants.

Figure 14. An example of how the different panels thicken each other through iconic solidarity can be found in the strawberry poster. In the top left corner, workers in full protective hazmat gear are spraying the monoculture field with pesticides. A bee that is feasting on the flower in the main anatomical panel gets a shower of the pesticides through the overlap of the panels. The strawberry plant then reaches into other thickener panels as the eye trails further down, connecting among other things to a swarm of wild pollinators of different species to the left and a sunny sky over workers picking strawberries in the bottom right corner. New poetic and associative meanings arise out of the collision of all the images and their different concepts and emotions – the creepiness of the crop sprayer’s almost skull-looking mask and strange protective gear contrasts with the intimate close-up of the loving and joyful meeting between flower and insect and the bumblebee leaping out of the sun-drenched field where a strawberry harvest is taking place in the bottom right corner. The monstrous and ghostly coexist through this overlap. The images do not form a set narrative with a clear reading order through standing together in this way. The bee exists in several places and times at once; it is in the crop-sprayer’s field, getting killed by poison, but is also buzzing, feasting and bursting with life in other realities/facets of plant–pollinator–human relationships. Poetic comics allow for thickening by offering several different readings and potential meanings simultaneously.

The series of posters tell stories of plant–pollinator–human relationships in the past and present, as well as speculate on futures. We argue that the combination of posters and embodied experience of making hand pollination tools can set ecosocial imaginaries in motion that can stay with the trouble (Haraway Citation2016) of being human in a time when dominant thin stories grant humans either no agency or too much agency in plant–pollinator–human relationships.

Ecosocial Imaginaries

The stories we tell in various media and settings influence actions and what is possible to even imagine. Stoddard et al. (Citation2021) define social imaginaries as ‘collective images of how we might live’ (12.23) and state that it is necessary to develop them to address the impact of high-carbon lifestyles. However, as Haraway (Citation2016) argues, current imaginaries of how to shape the future seem to be stuck in two polarised narratives. Either we are confronted by narratives that proclaim game over and that there is nothing to be done or we are confronted by narratives that are guided by an ignorant optimism and the idea that continued technological development will save us all. These overarching thin narratives are also noticeable within contemporary imaginaries of pollinators.

One of the scenarios relays that insect pollinators will suffer mass death, and many species will go extinct. In this narrative, the story goes that there will be a loss of food, livelihoods and life opportunities for humans and other beings. This connects to other pessimistic tales about an unliveable world and a disastrous future. It is connected to passivity and hopelessness, stemming from a sense of little agency where no action can make a difference. The future is thus a lost cause, and humans cannot do anything about it.

Another dominant story is that technical developments will solve all environmental problems, including the loss of pollinators. In this cluster of future scenarios, there are examples of technological drones, for instance, that will take care of the pollination. Another version leans more towards biotechnologies with the development of controlled reproduction of pollinators that can be further controlled in the field. These are examples of trying to solve a discrete problem – that of pollination – without looking at a bigger set of relations, such as where and how the materials for the drones are sourced and how it affects an ecosystem to blend in species that have been bred in factories. In addition, from a feminist perspective, these stories do not challenge current power hierarchies, economic exploitation, production structures or narratives of eternal economic growth. Therefore, none of these dominant stories addresses the underlying problems of power, suffering and ongoing life. Rather, they lack the perspective of care and solidarity.

These thin stories are present where worldviews are formed, for example, in education. Stoddard et al. (Citation2021) write that educational institutions are complicit in holding back imaginaries for a life liveable for many: ‘Universities have systematically excluded or sidelined many knowledge traditions not associated with industrial modernity’, which is ‘tied to an “epistemological monoculture” that has impoverished the collective global capacity to imagine and realize forms of living not dependent upon exploitation of people and natural “resources”’ (12.23–12.24). Stoddard et al. (Citation2021) point out that imaginaries of futures are currently not appropriate for what is needed because they are too embedded in, for example, the fossil fuel industry and, as Feola (Citation2019) puts it, colonial heritage.

Because these thin stories are the norm, they have become self-evident to a point that they might seem like the only option. Our design response seeks to present such thin stories as only one possible imaginary of what the future of pollination might be like. By making the thin stories present as panels along with other stories in the posters, we allow them to take up space as one of many alternatives, thereby thickening the present stories. For example, in the poster on strawberry, we show box-bred bumblebees as an example of a technological fix. The idea for this panel emerged when one of the authors noticed a box with bumblebees while picking apples in an orchard. This observation sparked curiosity, and we found that among fruit and berry growers there is a practice of ordering just-in-time bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) intended for pollinating crops and boosting the harvest of fruits and berries. Taken on its own, this is a panel of a thin story, suggesting to the viewer that there is an efficient technological solution to the discrete problem of declining numbers and varieties of pollinators. The story of factory-bred bumblebees shipped over distances longer than the pollinators would fly themselves comes across as simple and ready at hand. It repeats the pattern of transposing industrial production approaches into all kinds of problems. It also leaves out the thicker story of how the problem could be understood in alternative ways and how humans are part of figuring out the human–plant–pollinator relationships over time and space. We have picked up on weak signals of difference in academia and elsewhere that we have found helpful and explored the possibility of telling other stories through feminist work that can suggest methods for liveable futures.

Feminist and Designerly Methods – An Assemblage for Thickening of Stories

What kind of feminist imaginations can we as designers contribute to cultivate? What methods can we suggest? If we are to make thick presents and futures, how do we go about it?

Both feminism and design have methods of making things known – observing and noticing – as well as legacies of developing methods for imagining futures (see, for example, Rosner Citation2018; Søndergaard et al. Citation2023, july). There is thus a joint disciplinary interest and practice in future-making.

However, neither feminism nor design is singular. So, when the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES Citation2019) says that ‘the abundance, diversity and health of pollinators and the provision of pollination are threatened by direct drivers that generate risks to societies and ecosystems’ (33), many different solutions can be imagined for how to address this anticipated future through combinations of feminism and design. The IPBES states that wild pollinators in particular have declined in numbers and diversity, whereas there has been an increase in managed Western honeybee hives. Smith et al. (Citation2022) looked for the consequences of the decline in pollinators and found through their combination of cross-disciplinary data that ‘suboptimal pollination appears to be already driving significant excess mortality globally and loss of economic value in producing regions’ (127003-9). Whereas Smith et al. (Citation2022) write that there is a ‘remarkable consensus’ on the efficiency of the strategies to ‘increase flower abundance and diversity on farms, reduce pesticide use, and preserve or restore nearby natural habitat’ (127003-10), the IPBES (Citation2019) suggests addressing the decline with strategies that ‘range in ambition and timescale from immediate . . . to relatively large-scale and long-term responses that aim to transform agriculture or society’s relationship with nature’ (33). As the authors of this article, we pick up on the IPBES’s point of imagining how the relationship between nature and society can be configured. We do not know of any one method to do so but will make a point of combining many into an assemblage (Law Citation2004) that at least can sustain hope.

Method Assemblages for Knowledge Production and World-making

Our first starting point is that ways of knowing, methods, are always situated (Haraway Citation1988; Lury and Wakeford Citation2012). We anchor ourselves in the physical space of the Un/Making Studio in Southern Sweden, Northern Europe. The studio started with the premise that designers and design researchers need to expand the repertoire of solutions to contemporary challenges. Making new and more products, services, and solutions of various kinds has served many humans well, but with a more holistic approach, we can see that the search for efficiency and productivity has also harmed ecosystems. Therefore, the Un/Making Studio set out to explore the friction and possibilities of both making and unmaking. Saskia Gullstrand, a comic artist and an educator who has taught printing techniques came into the Un/Making Studio with references to storytelling and world-making that were new to the three other authors. Gullstrand’s references included reflections on line art in sense-making, comics as research communications published in major printed newspapers with a global readership, environmental and feminist activist methods anchored in specific struggles, and ways of multiplying and spreading a message through risograph printing. Åsa Ståhl, Li Jönsson and Kristina Lindström had a base in feminist technoscience and Scandinavian participatory design work. As part of their pedagogical design endeavours, they have, for example, co-hosted a summer course on ‘design and care’ that included a focus on multispecies co-living.

Feminist Methods – Assembling from Many Sources

The feminist work that this article draws on stems from various kinds of future-making: activism, feminist scholarship and more. It travels over time and place. We let this section swell and meander because if we are to imagine other futures, we need to be aware of what we draw on and that our situated knowledge production will always be partial.

Feminist Technoscience

Feminist technoscience is one anchor point for imagining alternative futures. In particular, in the three following feminist technoscience scholars’ work, there is an outspoken need for a recognition of deep entanglements of different actors that together create life across time and space.

In dialogue with and recognition of the major societal and planetary challenges in the Anthropocene, Tsing et al. (Citation2017) articulate that we live on a damaged planet. The authors suggest cultivating the art of noticing life in the ruins (Tsing et al. Citation2017). The noticing is done in many ways, for example, through senses and concepts such as ghosts and monsters (Tsing Citation2015; Tsing et al. Citation2017). That includes awakening one’s senses and attuning them to the things that seem out of sync, as well as to things that seem mundane. Ghosts and monsters have different capacities, according to Tsing et al. (Citation2017): ‘Against the fable of Progress, ghosts guide us through haunted lives and landscapes. Against the conceit of the Individual, the monsters highlight symbiosis, the enfolding of bodies within bodies in every ecological niche’ (M2-3). The noticing is place-based but also ready to connect between actors, places and temporalities.

In a state of severe uncertainties, Haraway (Citation2016) suggests setting up a curious practice of visiting as a way of recognising how the world is becoming in a dance between different actors. She emphasises the importance of staying with the trouble rather than continuing with business as usual or giving in to hopelessness (Haraway Citation2016). Decades ago, Haraway (Citation1991) pointed out the relationship between legacies, how they can travel into category-making, as well as how borders between entities can be the stepping stone to (ir)responsibilities in change work when she wrote of the cyborg:

The cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centres structuring any possibility of historical transformation. In the traditions of ‘Western’ science and politics-the tradition of racist, male-dominant capitalism; the tradition of progress; the tradition of the appropriation of nature as resource for the productions of culture; the tradition of reproduction of the self from the reflections of the other – the relation between organism and machine has been a border war. The stakes in the border war have been the territories of production, reproduction, and imagination. This chapter is an argument for pleasure in the confusion of boundaries and for responsibility in their construction. (151)

Feminist technoscientists such as Tsing, Haraway and Puig de la Bellacasa all use everyday situations such as composting, foraging for mushrooms, living with your dog and mundane engagements as ways of knowing and making worlds. They show that knowledge production is local, embodied and situated while at the same time connected to that which surmounts what is easily graspable. They show the generative approach of focusing on humans in relation to other actors that can make things happen. For example, these feminist technoscientists help move the imaginary from ideas of discrete entities into entanglements across time, space and actors.

Thin stories of clear-cut boundaries between, for example, nature and culture have thus been challenged by feminist technoscientists (Lorenz-Meyer, Treusch, and Liu Citation2017). They have also given suggestions for how we can understand relationships in other ways, for example, through the cyborg, multispecies co-living and foraging. For us, orientations of this kind, changing from thin stories of limited presents and futures into thickening them with stories and located as well as embodied situations for sense-making, became important in developing methods for working with the contemporary dual lack of social imaginaries and biodiversity.

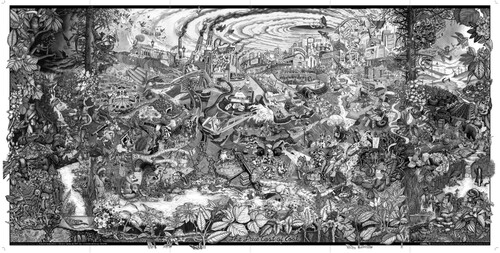

Visual Contemporary Methods

For the work on methods for visualising human–plant–pollinator relationships, Gullstrand brought in the feminist Beehive Collective’s graphic work for us all to build on. Pujadas (Citation2022) characterises the Beehive Collective’s work as ‘graphic art as an educational tool when sharing stories about resistance in the face of corporate globalization’ (23). The poster called ‘The True Cost of Coal’ shows the struggle for ‘land, livelihood, and self-determination’ in the coal communities of Appalachia, United States (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.a).

Beehive Collective (Citation2021) describes themselves as

a collective of artists, activists, educators and organizers who work as word-to-image translators of complex global stories, shared with us through conversations with affected communities. We then share those images and stories with many communities in the form of graphic storytelling. (para. 1)

They must be real stories that occurred in the same place that are only shared with them through oral transmission from the area’s inhabitants. They do not use news from the press or any other media. These human encounters alone make it possible to compile the stories (Pujadas Citation2022, 23).

The Beehive Collective’s production methods seem to be characterised by time and collectivism. Listening to, collecting and researching stories on the ground can take several years (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.b). This is followed by an extensive period of finding connections between the testimonies, creating visual metaphors to depict the stories, drawing large-scale ‘murals’ on paper with ink and reconnecting with the involved communities and organisations for critical feedback on the visuals (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.c). ‘The True Cost of Coal’ was not only drawn by the Beehive Collective but made in collaboration with hundreds of grassroots organisations and activists from the Appalachian Mountains, as well as other places of the world. Noteworthy is thus that many voices are gathered in the poster. It was not made by one artist but by many contributors of stories and visuals (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.c). The poster travels with ‘the Bees’ through storytelling and workshop tours but can also be downloaded by anyone from their website and used at, for example, all kinds of community events, at protests or within school or research contexts (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.c).

The visual aesthetics should be analysed in light of the Beehive’s effort to offer the world ‘popular education tools, both to plant the seeds of critical thought and resistance and to support ongoing organizing and movement building’ (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.c). The style and composition should help an onlooker to ‘break down big issues from the overwhelming world we live in and present them in accessible, engaging formats’ (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.c) The design is characterised by a multitude of elements by which to be amazed. It is swarming with detailed drawings of animals, plants, landscapes, buildings and machinery. There is a focus on actions, conflict and communities in a troubled, pained and growing world. The Beehive does not portray humans but rather draws ‘zoomorphic’ characters in the genre of fables (Pujadas Citation2022, 23).

‘The True Cost of Coal’ is a rich retelling of the struggle and resistance against coal mining, structured into five different chapters showing (1) ancestors, (2) industrialisation, (3) mountaintop removal and climate chaos, (4) resistance and (5) regeneration (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.b). The poster is folded. When it is closed, you see a mountain landscape bursting with life, but when you open it up, it reveals the heavy conflict of coal mining underneath, as well as the struggle and resistance of communities living in Appalachia (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.b). A great number of scenes play out at the same time in the landscape, organised into smaller compartments/rooms/glades in the land. The scenes organically connect and grow into each other through a flow of overlapping characters and objects. To read the full story, you have to zoom in on each scene to see what specific aspect of the story is told there. Every scene depicts animal characters involved in often suggestive and sometimes surreal activities, and the viewer must interpret what is actually happening and what it signifies.

Notably, the poster is in black, white and grey only. Participants can colour the poster, which has been a way of getting people into the story (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.d). The plants, animals, buildings and machinery are portrayed through a soft and organic realism that for us conjures up associations of illustrated encyclopaedias of natural life, beautiful children’s books or certain genres of tattoo art. Shades and textures are painted with incredible detail, turning the landscape into an interplay of greyscales. The line art flows and surges with varied brush strokes and widths of pencil line. Often, the soft shapes created by different values of shading are what construct and separate creatures and elements from each other and from their surroundings – not the line art. The result is a world that seems to consist of an endless and alive complexity that encourages and attracts as well as demands you to come closer, engage and spend a long time in the reading process.

When it comes to methods of reaching audiences, the Beehive Collective has decided that the poster is ‘anti-copyright, but also licensed under the Creative Commons’ (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.d). People are thereby encouraged to use it for educational, activist and creative purposes to activate the artwork and its stories. On the Beehive Collective website, you can download free web and print versions of the poster, as well as find guidelines on how to read it and inspiration on how to use it. Beehive members have also toured with the poster and offered sessions where live storytellers point out and narrate different sections of the mural to an audience (Beehive Collective Citationn.d.c).

Feminist Legacy Where One Is Situated

Methods of trying to make thick presents and futures include turning to those who have gone before us for inspiration, strength and solace. Forerunners can be formalised academic references or inspirational activists. In our own geographical location in Sweden, we decided to bring the author, activist and feminist Elin Wägner into our palette of references. That was an active work of including a person who, at the beginning of the 1900s, was denied higher education due to being a woman. As an adult, Wägner used, for example, novels as a way of imagining other lives and sharing those stories. She participated in collecting signatures to put pressure on the Swedish parliament to allow women the right to vote in democratic assemblies. The collective work succeeded eventually (women could vote in Sweden for the first time in 1921). She criticised life-damaging efficiency-seeking processes and the use of chemicals in the production of food.

Gradually, Wägner’s way of sensitising herself to the ongoing world-making seems to have led to a deep engagement and sharing of not only the social conditions for some groups, such as children or women, but what we would today perhaps call global socio-ecological justice. She was part of starting a biodynamic farm in southern Sweden. Although she acted mostly in Europe, she also worked for global solidarity for the creation of good lives. For example, in one of her last books, Alarm Clock, she wrote,

One could only talk of a high standard of living once one knew as much about the conditions of the workers in the food industry as about the livestock and crops. We had all served the delicious, cheap Californian fruit at our Sunday dinners. Now we had found out why it was so cheap. American farmers, transformed into a proletariat by crude, ruthless agriculture policies, had flocked to California to work, picking and preserving fruit in conditions one would not consider fit for dumb animals. For as long as the apricots, coffee and oranges we are serving were still tainted by want and tears, we remained far below a humane standard of living. (Wägner [Citation1941]1990, English translation 1999, 50)

In regard to active reference-making in building futures, feminist work such as that of Wägner and her allies might have to be sought in novels because Wägner was not allowed to study and make her knowledge production part of formal academic structures.

Methods Assemblages for Knowledge Production and World-making

The three clusters of method references that have been introduced in this section – feminist technoscience, historical ecofeminism through Elin Wägner’s books, and civic work together with allies, as well as current activist work through visual narratives by the Beehive Collective and collaborators – are here to show how method assemblages (Law Citation2004) can be built up for world-making. Bringing in both academic and non-academic references from various epochs and places and allowing them to cross-pollinate is a method of combining voices and practices that we draw on in our joint work.

In addition, the following can be highlighted: All three clusters of method references work with a profound and integrated entanglement approach. This includes temporal understandings and enactments that break with linearity. The work is anchored in place and materiality but also works with radical solidarity across actors, time and place, such as the expression of solidarity as an eater in Europe with those working in canned fruit production in California. The presence of ancestors and the surreal elements in the Beehive Collective’s work resonate with how Elin Wägner allowed new academic findings to intermingle with myths in her writing. This teaches us to build up relationships across time, actors and place and to move between them whether they are tightly knit together or not.

All three are examples of practicing amazement through noticing, observing and curiously becoming together that can help imagine other worlds. They cross over between binary distinctions such as nature and culture, as well as human and more-than-human actors. This comes out strongly in Elin Wägner’s mundane methods of ‘reading’ the landscape in one’s nearby surroundings for prompts for speculative and prefigurative work. With that approach, the gaze can be turned towards the relationships between pollinators, red clover, almonds and strawberries. Together with activist work and feminist technoscience, we are taught to dare to pick up threads from everyday life and to imagine alterations. We are also, such as through the Beehive method of relying on primarily oral sources from those who have been touched by a matter, reminded that we must actively go beyond our own experience and into a mode of listening, interpreting, retelling and amplifying radical narratives that do not have the resources and capital that the fossil fuel industry does. In addition, we are taught that knowledge production and living are inseparable. Furthermore, as Gibson–Graham wrote in Citation2008, ‘Not only are academics becoming more involved in so-called scholar activism but they are increasingly conscious of the role of their work in creating or ‘performing’ the worlds we inhabit’ (614). Design researcher DiSalvo (Citation2022) addresses the engaged scholar who is involved in world-making and knowledge production also with projects that are ‘fragile, partial, and compromised’ (7).

Design – A Positioning Amongst Strands

Some strands of design are entangled with industrialisation and the creation of desires to consume, for example, products or services that promise to make life easier and more comfortable. This strand is prone to taking others’ problem articulations or articulating problems in ways that make it possible to solve them through set methods, often with universalising claims (Pujadas Citation2022). The tenuousness that DiSalvo (Citation2022) refers to is not acknowledged in this strand. Rather, with the risk of losing out on nuances, this strand represents the making of more beehives or even of making more pollinators and putting them in areas where one wants to increase the yield as an answer to the loss of pollinators.

As educators in programmes in higher education who train students in creative expression, we can zoom in on, for example, design education and what imaginaries it is building towards. Boehnert (Citation2019; see also Boehnert Citation2015) points out,

Institutions that establish legitimate knowledge in design have dismissed environmental concerns in theory and practice (through activities like curriculum development, journal reviewing, hiring decisions, etc.) effectively stalling the sustainable transitions. The clear dangers associated with climate change should help ecological theory move beyond the margins. But this challenge constitutes a paradigm shift in design education and the design industry as it radically revisions what constitutes ‘good design’ – and so progress is agonizingly slow. (1738)

However, there are other strands of design that divert from ‘free-market ideologies’ (DiSalvo Citation2022, 180), constant economic growth, and rather strive for, for example, a desire to understand more. These strands are characterised by exercising a critical stance towards systems that strive for constant economic growth through the making of new products that might make life easier for the already privileged. This strand also recognises that if we set out to address wicked problems (Rittel and Webber Citation1974) as discrete problems to be solved, we set ourselves up to fail. Instead, we need to develop ways of living with the complex situations that arise or continue over time. In that sense, it overlaps with methods of performative and experiential art, sustainable pedagogy and more. At the intersection of speculations, criticality and participatory design, there are also robust overlaps with feminist technoscientists such as Tsing et al. (Citation2017), who recognise that we live on a damaged planet and that one way forward is to, in the words of Haraway (Citation2016), stay with the trouble and with Puig de La Bellacasa (Citation2017) speculate on multispecies care for liveable worlds. This latter strand of design in combination with feminism is thus a reference for the context of designing as well as methods for designing and imagining worlds – new or revived.

The alarming situation with loss of biodiversity, and the intersecting crisis of climate change and social crisis, can be taken as a pressure to prototype and share methods for successful mitigation of these crises. With such grand-scale challenges, do we dare to pair up with the legacy of feminist methods that deal with the small, mundane and everyday (DiSalvo Citation2022; Jungnickel Citation2023)? If we push the premise for future-making and ask what if a single focused search for large-scale success is part of the failure, do we then dare to share that which does not score high on success, impact and performance indicators?

Learning to Work with Relationships

In the education field, pedagogical sustainability approaches are spearheading a shift in educating for ecosocial imaginaries. Wamsler (Citation2020) writes that ‘more holistic pedagogies are urgently needed to address today’s challenges, as education is one of the most powerful and proven vehicles for sustainable development’ (113). Her suggestion to address global, wicked issues is a turn towards inner transition in sustainability education because much of it focuses on ‘the external world of ecosystems, wider socioeconomic structures, technology and governance dynamics’ (Wamsler Citation2020, 113). Additionally, Leichenko and O’Brien (Citation2020) connect the self to structures and systems. They write, ‘The personal sphere of transformation is where students can explore how beliefs, values and worldviews – including their own – influence how they relate to climate change and how they engage with solutions and actions in political and practical spheres’ (Leichenko and O’Brien Citation2020, 3). Through experiential learning, one can activate ‘a sense of individual and collective agency’ that can expand from the classroom to ‘larger-scale changes’ (Leichenko and O’Brien Citation2020, 3). They argue that to tackle changes, such as climate change in the Anthropocene, scientific literacy does not seem to be enough. Their suggestion is a holistic approach that emphasises relationships on many levels, such as ‘to see climate change as both an environmental and social problem that is rooted in particular understandings of human-environment relationships and humanity’s place in the world’ (Leichenko and O’Brien Citation2020, 3). More concretely, education for change then includes experimentation, so ‘students become aware of the relationships between individual change, collective change, and systems change’ (Leichenko and O’Brien Citation2020, 3).

The way this section is written with different anchoring points and legacies in combination is thus a segue to the enactment of how multiple voices in storytelling in communicative settings can come together without necessarily adding up. This will be further explored in the next section on our joint creative expressions.

Artistic Expressions

Learning from our motley crew of feminist references, with its long legacy of trying to make the world different through different means, both knowledge production and world-making through cultural production, we set out to make posters and create situations around them.

Our first step was to expand the social imaginaries beyond the often-repeated thin human-centeredness. Our feminist references across time and place emphasise the importance of understanding the actors in the world as interrelated. That means, for example, to take the categories of the social and the ecological together. This provides grounds for ecosystemic imaginaries that leave neither bumblebees nor humans or plants behind but rather search for the boundary work that needs to be done between the categories of the social and the ecological.

With our insights into art and design education, we are increasingly aware of our own hesitations. If art and design are based on paradigms of, for example, modernity, anthropocentrism, universalising claims of solutions to discrete problems, then a turn towards art and design might not be able to provide transformative cues. If the creativity is aimed at building another beehive with controlled animal pollinators, then it is not an expanded ecosocial imaginary that is introduced. How do we, entangled as we are, keep ourselves from falling into the same trap? We ask ourselves: what expression can we muster up for creating feminist futures, torn between the references that we want to build upon and the references that are dominant? How are such world-making approaches related to knowledge-producing methods?

We will now give an account of our design choices and interdisciplinary learnings.

Un/Making Pollination Poster-making

Prior to starting the poster creation, Ståhl, Jönsson and Lindström had approached loss of biodiversity by inviting participants to make appetizers from food and drink ingredients that we hoped would amplify engagement in the decline of pollinators. We tried setting up a situation for the participants to experience the labour that it takes to keep thick presents of having lively human–plant–pollinator relationships alive. This is where Ståhl, Jönsson and Lindström first had a nagging feeling of not having succeeded with what we aimed to do. There were promising aspects of the method we had developed of making future-oriented appetizers and recipes: the collective embodied storytelling, the multimodal communication about the diminishing number of pollinators and how that affects futures, as well as our speculative and factual thickeners combined with the sweaty and sticky work of making the appetizers. We published what we found to be possibilities for thickening presents and futures through embodied engagements (Jönsson, Lindström, and Ståhl Citation2021). The sweet stickiness of own-made marzipan and a sparkling drink of fermented honey seemed to turn the thickeners, the stories of human–plant–pollinator relationships, into background material. One of the things we struggled with was that the stories became too thick to navigate (Jönsson, Lindström, and Ståhl Citation2021). Our training in the feminist work of sustaining hope through modest alliances pushed the three of us to go on by involving Gullstrand for help in continued explorations, combining feminist and designerly methods for practicing imaginaries of what is to come.

In the Thick of Artistic Expression

To develop and share ecosocial imaginaries with others, the collaboration between Ståhl, Jönsson and Lindström, and Gullstrand started. Through poetic botanical posters, hand pollination tool workshops and an attentiveness to place in public engagements, we aimed to bring people closer to the interspecies pollination labour, to open up feminist ecosocial imaginations of how to shape and organise these reproductive relationships in the future.

The method assemblage that we activated was sprawling. Apart from meeting in various constellations between the four of us, the collaboration also included field visits, with interviews and observations, to a botanical garden and to one of the few nut orchards in Southern Sweden where growers are trying to establish an almond orchard. Because we were looking for updated scientific facts, we conducted interviews and meetings with researchers on pollination issues to deepen and clarify our knowledge and to continue learning about pollination; this included primary research sources as well as popular science communication. In addition, we dove into sources on historical, contemporary and speculative folk approaches to red clover, almonds and strawberry. Together, the four of us gathered visual material from communication campaigns, children’s books, flora, and Swedish school posters from the twentieth century depicting the plants and pollination processes. We shared our background material in an online document and analysed the material together. We narrowed aspects down to a few that should appear in each of the three posters as educational motifs and thickeners of different kinds. They included the following: the biological bodies of the plants, specifically showcasing the flowers as reproductive organs; how landscapes are shaped by current agricultural practices; the plant as a cultural object in human mythology, folklore and folk practices; threats to pollinators or plants, such as pests and illnesses or climate change disturbing the time of the flowering season; food production for humans; productivity; humans’ involvement with other beings and role in pollination in the past; and human strategies for managing pollination in the future, for example, breeding self-pollinating almond trees, using the clone reproduction functions of red clover, or industrially breeding insect pollinators and shipping them to the crop fields just in time.

The posters had a pedagogical purpose as well as igniting ecosocial imaginaries. They should offer knowledge-based stories of the past, present and possible futures of pollination as something graspable for the viewer. At the same time, they should attract and invite the viewer into experiencing the alluring and frustrating complexity of the relationships at stake, functioning as a tool to stay with the trouble. Could this be achieved through offering the posters as a place for spending time with the relationships, feeling, fantasising, dreaming and failing to reimagine them? To achieve both qualities, Gullstrand combined inspiration from two visual traditions close at hand for her in the creation of the posters:

Modernist Swedish school posters presenting edible plants or insects republished in Wahlstedt’s (Citation2000) book on onlookers’ pedagogies.

Contemporary wordless poetic comics drawn in a ligne claire style with experimental panel grids used as illustrations for newspaper articles and texts in magazines about science, culture or technology, among other things.

School posters are a visual expression that was used as a pedagogical tool in Swedish schools mainly from the mid-nineteenth century up until the 1960s (Wahlstedt Citation2000).

Gullstrand recognised posters as a pedagogical expression that is confident in its own authority to teach, categorise and explain the world for students. By examining biology posters presenting species and processes in nature, Gullstrand found that many include the following:

Temporal qualities, showing development over a lifetime (from egg to larvae to pupae to grown insect or seed to flower to fruit)

Close-ups of small details, for example, depicting a bulb as much larger than it is in real life so that small details that otherwise could be easily overlooked appear clearly and can catch the viewer’s interest

Cross-sectioned objects show what is hidden inside, such as a hornets’ nest hidden inside a tree trunk (Wahlstedt Citation2000, 106) or the layers of starch grains, sugar and skin of a potato (Wahlstedt Citation2000, 68).

School posters, therefore, give the viewer perspectives beyond what would be available by just looking at a flower in bloom or an adult bumblebee caught in a glass jar. They paint a picture of processes (such as aging) and relationships (such as how a polypore grows out of a tree trunk) and enlarge details that otherwise would go unnoticed.

Contemporary poetic comics, on the other hand, is a genre whose strength lies in ambiguity, association and the lyrical. Comics theorist Thierry Groensteen (Citation2013) points out that no matter how traditionally narrative a comic is or is not, the separate images within it always operate with an iconic solidarity, meaning that they support each other as a meaningful whole and depend on each other to be read and interpreted. He differentiates between three levels of narration within comics through the concepts of string (abstract comics), series (poetic comics) and sequence (traditionally narrative comics) (Groensteen Citation2013). Poetic comics are ‘characterized by a poetics of reticence, ambiguity and indeterminacy’ (Groensteen Citation2013, 30). Creators of such comics ‘create connections between panels that work through harmonies, resonances, correspondences, eschewing the kind of relationships that are immediately decodable in terms of narrative logic and meaning’ (Groensteen Citation2013, 30). In other words, comics can carry meaning without simplifying the images into a clear traditional story but instead rely on the reader opening up to an experience of association and lyrical connection.

To study two in-practice cases of how contemporary poetic comics function, Gullstrand turned to the works of artists Cristina Daura and Fien Jorissen.

Daura’s visuals are lush, surreal and metaphorical, often combining one larger image with a set of smaller panels that visually comment or expand on the scene presented in the main illustration. These smaller frames often show a cinematic flow, resembling animation. A key feature of Jorissen’s comics is her experimental grids, where comic panels often overlap each other and with multiple possible reading paths for the viewer. There is usually not a clear reading order to the images – your eye can choose different paths among the images and connect them into different impressions and sequences based on these paths. For line art, the ‘seam’ that holds together and separates the panels, both artists use their own version of an elegant ligne claire drawing style to create and combine atmospheric, suggestive and beautiful images into ambiguous narrations that require careful observation to notice and engage with all the details in every panel.

Our Un/Making Pollination posters were designed in dialogue with both the traditions above. Furthermore, in dialogue with pedagogical, popular scientific communication, Gullstrand borrowed the concept of a large, central portrait of a plant in bloom as the main focal point from school posters. Several insects are depicted on and around this plant, showing the act of pollination. We think of this image as portraying a kind of lovemaking, seen through a sort of pollinator’s gaze, hoping to create an attraction in the viewer and a desire to participate. The strawberry and red clover are drawn as full-body plants with roots, stems, branches, leaves, flowers and fruit, whereas the almond is represented through a few branches with flowers, fruit and leaves. The attention to the anatomical is factually correct to teach about the actual reproductive functions of the plants. The pollinators in the posters are depictions of species that would visit the plants in real life, drawn to be recognisable and distinct through different body shapes and sizes, fur textures, fur patterns and wing shapes. They either cling to a flower, gathering pollen and nectar, or are seemingly leaping towards one, fully focused on reaching the flower. Below the main image, a slightly enlarged black-and-white sectioned flower is located at the bottom of each poster. This is a reproductive flower model to aid someone who is designing their own pollination tool for the specific plant in a public engagement event.

From the poetic comics of Jorissen and Daura, Gullstrand was inspired to work with an experimental layout structure of comic panels around the main image, a grid that could make a set of fragmented, emotion-evoking and suggestive retellings of and speculations on plant–pollinator–human relationships stand in solidarity together, coexisting and drawing on each other for meaning. This resulted in what we call thickener panels.

The balancing act between demanding content and clear line art that makes relationships noticeable in Daura’s and Jorissen’s work was also explored. Ligne claire not only includes clear ink lines, flat colours and geometrical precision (Miller Citation2007), but it is also economical, with no unnecessary details that can distract or confuse (La Cour, Grennan, and Spanjers Citation2022). The lines are of almost equal thickness in all parts of the images, the areas of the image are clearly divided, and the colours are flat. Comic artist Joost Swarte coined the term ‘ligne claire’ in 1977 to describe Hergé’s drawing style and way of working with narrative – a clarity of thought that comes through in the line art, the page layout, the narrative and the construction of the story (La Cour, Grennan, and Spanjers Citation2022). Contemporary ligne claire styles are, for example, how Christina Daura and Fien Jorissen use them.

For us, there was an aesthetic dilemma in the question of line art style as a way of conveying entities and relationships in our imagery. For a design that is all about showing thick presents, where multiple relationships coexist and affect each other, should you not turn (like the Beehive Collective) to a style that can conjure up a rich world of greyscales and endless nuances? Pencil art could, in a similar way, incorporate effects such as cloudy textures and smudges, where one shape in the image bleeds into another. Because of the lack of clarity and borders between different elements, we pondered choosing such an approach for our posters.

On the other hand, there is a risk of becoming exhausted when trying to engage with wicked issues – they can feel too big and muddled to be approached at all. Ligne claire, according to Bruno Lecigne (Miller Citation2007), implies that the world is legible. If the creative expression can help the viewer/reader stay with the trouble and keep engaging with the artwork, the images have a better chance of nurturing imaginaries and the capacity to respond in a world of wicked problems. The themes and the layout structure already provided a large and demanding complexity in our posters. We therefore decided to try using a drawing and colouring style for the Un/Making Pollination posters that can be described as a contemporary practice of ligne claire. Gullstrand made thin, black ink lines of similar width, used flat colours and employed geometrical precision in the shapes of objects and distinct image elements that are clearly divided into different areas of the panel. This was done to achieve a stylised documentary quality – a clarity by which the viewer can take in all details (see, for example, La Cour, Grennan, and Spanjers Citation2022; Miller Citation2007).

Stylised Clarity

The informative line art expression was chosen because it came across as an attractive way of making sense of relationships. It seemed to fit well with the project to be able to go into small details with precision on the line art level and to ensure all the elements in each image would be distinguishable from each other.

One example of an informative section of the posters is red clover roots in symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. The bacteria fix free nitrogen from the air, which benefits the plant. In return, the plant supports the bacteria with salts and carbohydrates. Another example is a nectar-robbing bumblebee that bites up the flower bud of the red clover to get to the nectar. Not all insects that take nectar from the red clover are pollinators. Nectar robbers are organisms that feed on nectar via holes bitten in flowers, often without providing pollination service.

In other aesthetic choices, we turned away from an infographic and realistic look because our feminist references, such as the Beehive Collective, ecofeminist Elin Wägner and technofeminists, helped us open up space for a combination of factual and magical elements. The motifs are imaginative interpretations of the concepts that we wanted to communicate. The bumblebee boxes in the postal service warehouse, a woman sipping from a mug of red clover tea in which a single large flower is floating, and the spooky mask of an agricultural worker spraying strawberry crops with pesticides are all surreal and heightened visual depictions. We use the power of illustration to combine objects and situations into emotion-evoking scenes that can create fascination and association, as well as highlight unnoticed processes and relationships or offer an emotional understanding of the world. We use bold colours that differ from reality, silhouette aesthetics and a graphic drawing style that does not try to resemble photographic realism.

Discussion: Un/Making Pollination Posters and Beyond

The complexity of many issues, such as loss of pollinators, is daunting. It can be difficult to navigate in complexities and easy to turn to more of what is already known: more efficiency and, for example, more domesticated and bred honeybees. Where do we practise ecosocial imaginaries that go beyond thin narratives?

Given these circumstances, it can be difficult and courageous to open up to one’s own reading of the world and sense-making that imagines alternatives to the decline of pollinators.

The posters we have created show pollination relationships among insects, humans and three plants that play a role in human food production: strawberry, almond and red clover. At first glance, the posters present lush imagery with food, flowers, swarming insects and landscapes. There are many details to look at, hopefully attractive and inviting the viewer to come closer and examine what is happening in each image. They do not advocate for a particular way of acting or for solving the complexities. Rather, they invite experimentation regarding how to understand thick entanglements.

The making of Un/Making Pollination posters drew on, as previously shown, contemporary activist work concerning, for example, extractivism of coal by the Beehive Collective, academic ecosystemic approaches such as feminist technoscience, and sustainable pedagogies as well as historical ecofeminist inspirations of allowing oneself to imagine alternatives to the present by being amazed. The posters were meant to be combined with a set of strategies to create attraction to and intimacy with the issue of the loss of pollinators while also practising ecosocial imaginaries. The posters have elements of clarity that we borrowed from the school posters and thin stories as we know them from, for example, dominant education and creative expressions.

Despite Covid-19, as part of the art exhibition ALT_CPH, we placed ourselves on a concrete boardwalk on the seafront in an inner-city area in southern Sweden. It is an area where very little grows, other than some trees planted by the municipality and some pots with seasonal plants. It could be understood as a thin future for co-living across species and particularly hard for pollinators to find habitats and food for reproduction.

For this occasion, we decided to focus on red clover and ecosystems of which red clover can be a part. A big pot with red clover in bloom had been nurtured on one of our balconies. We brought it. We also foraged red clover in other areas of the city and made cooling tea. Red clover is not one of those cute species that usually attract humans or cross one’s mind as related to food, but it has a role in feeding herbivores that fertilise the ground with their manure. The red clover has a long floral barrel that is hard for many pollinators to reach. The great yellow bumblebee, however, has a sufficiently long tongue. Its survival is threatened in Southern Sweden, partly due to how the land is farmed. However, the red clover is attractive to other pollinators who feast on the nectar by biting a hole in the flower. Thereby, the so-called nectar robbers take a shortcut to the nectar without doing the work of pollinating.

For making hand pollination tools to experience what it would mean to reproduce red clover through human hands, we also brought materials such as horsehair, human hair, sticks, leaves, glue, cotton buds, yarn and more. The posters were placed on the concrete boardwalk. The content of the posters was there as an invitation for viewers to thicken their understanding of the issue. In this very urban location, distanced from meadows and fields with grazing cattle, the panel at the top left on the poster with a cow eating red clover made it possible to bring in the co-living across species that allows for nourishing the ecosystem.

The posters’ capacity to amplify and bring in that which is hardly present was thus tapped into. Together with some passers-by, we tried to experience the act of pollinating red clover. This allowed us to get close to and sensitise ourselves to pollination. Trying out different materials and feeling the size of one’s hand in relation to the materials and the flowers lent to different relationships and borders between places, actors with different bodies, and imaginaries to be put into motion. Physically imagining that we were doing the job of pollinators became an exploration of relationships in which humans’ dominant ways of living and making dwellings impact the habitats and survival of other species.

Although the first participant we noticed on the boardwalk was an insect that potentially could have been pollinating, there was an overall lack of pollinators in the urban location. This situation could be approached with curiosity, as Haraway has expressed it, although it was not a comfortable or agreeable situation. Through experiential approaches such as creating hand pollination tools, one can dive into closer relationships between humans, plants and pollinators. This provides a moment of being amazed, not by nature as unproblematic or solely pleasing or attractive but by actors and places and actions coming together in ways that involve both making and unmaking lives.

This embodied experience together with others and with a ‘loud’ absence of some – thriving pollinators and plants – made it obvious that making hand pollination tools would not solve the issue at hand. However, trying to craft tools for pollination also worked as an invitation to practise the art of noticing. Our aim was never to propose the human hand as a solution to the lack of pollinators, although it has been and is used in both commercial orchards and private settings. Rather, there was a need for an imaginary move between the location with the human-made concrete and the thickeners in the poster. Whilst the posters can provide focus on what to notice as absences and presences in the concrete urban environment, they can also attract so much attention that the noticing of the real surroundings is blurred.

The thickeners in the Un/Making Pollination posters have clearly drawn lines between the panels that make for a legible world-making, but in combination with the setting in a particular location, the materials for hand pollination tools and the conversations, borders between entities can dance on the edge of being both legible and smudgy. The combination can call into presence relationships that have been known to make many humans, plants and pollinators thrive, as well as unmaking lives. Whilst these relationships are currently being pulled apart by the ongoing un/making of pollinating insects, we can challenge ourselves to answer with imaginaries that go beyond, for example, installing beehives. Natural scientists say there is a need for natural habitats and more and diverse flowers, as well as less usage of pesticides. Those of us working with artistic, creative expressions can communicate urgent complex issues through factual and accurate information as well as mingle temporalities and human and more-than-human bodies and choose locations in which to do so that make us amazed through both attraction and repulsion.

The question arose of how well the posters travel because they are always located in a place. The issue travels, but are the posters able to travel well? Within the author group, there is knowledge of and a leaning towards DIY and zine culture: letting things circulate in many formats. Therefore, apart from the riso-printed posters, we were also looking for other ways of reaching out. Inspired by the Beehive Collective, we made our posters downloadable from a website in black and white. Further explorations and reflections of the circulation are a way of staying with the trouble of starting off working with a medium that can travel beyond our control, rather than a particular audience. If we compare ours with the demanding work of the Beehive Collective that requires extensive engagement, such as self-colouring to be graspable, we have been working to offer different levels of engagement. For example, there are multiple ways of approaching human–plant–pollinator relationships at stake, and one can gain something from a quick browsing, but thick engagement is possible through the combination of a place, multispecies bodies coming together and explorations of amazement with relationships. Factors such as resources at hand and ambitions of radicality will determine each one’s approach.

Conclusion

This article presents the thin stories of two dominating imaginaries in relation to the loss of pollinators: one on hopelessness and one on technological fixes to discrete problems. These are repeated in education and in everyday life. We argue that there is a need for feminist methods that thicken the stories and presents for more liveable multispecies futures.

Our attempts to evoke amazement in thick presents were done through learning from and listening to the method assemblage of feminist technoscience, feminist visual artists and historical feminists. Drawing on these references, we collaboratively developed the poetic artistic expression of clarity and smudginess. The poetics of clarity and smudginess were, for example, manifested in the posters through working with attraction, where the relationship between pollinator and plant is central, and one is lured in by the vibrant colours, delicious fruits and flowers in full bloom. The motifs are filled with vitality and beauty at the same time as the viewer is expected to notice the upper left corner that depicts darkness – for example, pesticides in the strawberry poster. If one thinks of the poster as a space, then the viewer can be expected to scan and notice the coexistence through a dance between the relationship and combinations of death and life.

The artistic expression of clarity and smudginess can be found in the bold colours, and the ligne claire line art forms a stylised realism that offers further impressions of clarity and the world as a legible place. The grid of sharp geometrical comic frames also suggests that you are looking at a collection of elements that can be organised and understood. Biological facts about the plants and the act of pollination can be found in the central anatomical portraits, a design strategy borrowed from school posters that indicate authority and confidence that there are things to learn by looking closer and paying attention to physical bodies and processes. At the same time, smudginess is expressed through the image motifs combining everyday objects (for example a strawberry cake, and various containers of almond milk) with surreal and poetic scenes, such as the crop sprayer. The grid maintains openings rather than indicating a set order of how the panels should be read. Thereby, the viewer can choreograph their own reading as a dance between a combination of panels.

To bring this amazement into specific situations, locations and lives and practising knowing one’s world in embodied ways, these posters were activated in workshops where participants also explored the practice of hand pollination. The invitation to craft pollination tools was not intended to take over the roles of pollinators but to grasp a sense of understanding and get closer to the relational ties beyond the human eye to notice better that which performs life.

For some, to amplify certain discrete actors, times or places, and relations might not come across as an emergency and a crisis where the alarm bells ring. Even though our human bodies do not necessarily feel the evidence of the current unbalanced ecosystems, this is still about life and death for all bodies. Phrased differently, it is about amplifying things that otherwise would go unnoticed to take up space to infect and affect our thinking to allow us to stand in solidarity with not only Wägner’s fruit pickers in California but also nonhuman life forms. These acts of amplification, of trying to strike up a curious amazement, are far from discrete. Neither the posters nor the workshops are mundane, but they can instigate noticing in everyday life that travels far beyond the setting of the workshop and posters to be troubled and amazed in mundane settings, being troubled by the almond milk placed on the breakfast table, noticing the absence of pollinators in the urban space, or observing the box-bred pollinators in the apple orchard.

We argue that this methodological assemblage that includes eyes, hands and other sensorial actions in combination with concepts such as human–plant–pollinator relationships can cultivate the capacity for solidarity and create liveable futures. This includes noticing the labour of pollination, the absence and presence of pollinators as well as habitats, apocalyptic and technological fix approaches, desires and love as well as repulsion in relationships, and the importance of place-based work to sensitise ourselves to human capacities and limits – that which make up liveable lives over time and space and actors.

Rather than providing one preferable future or present, this work has set out to thicken the present. This means that we have nurtured an openness to categories and pollination relationships changing over time because there are many possibilities of how this can be done. Neither have we privileged sole clarity and technological solutions nor sole smudginess and game-over approaches because none of them is a thick way forward. Rather, the ambiguity makes it hard to distinguish between categories and thereby creates space for participation in staying with the trouble and relationship-building. In dialogue with activist work, feminist technoscience and historical feminist struggles, we have dared to work with the mundane in solidarity across, for example, species; roles of academia, art and publics; life and death; panels in posters; and places and habitats that do not have the resources of fossil fuel budgets.

Our contribution is thus a methodological assemblage of thoughts and practices that emerge through the making of and participating in artistic and creative expressions. Those are feminist methods of both clarity and smudginess that make hopeful liveable lives possible.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the ones who generously shared their knowledge with us and those who made this work possible, including our departments and Malmö Comics Research Lab.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Åsa Ståhl

Åsa Ståhl combines participatory design with feminist technoscience and environmental posthumanities in explorations and speculations of how to make and know liveable worlds. She has worked together with Lindström since 2003. The two set up The Un/Making Studio to explore alternatives to progressivist and anthropocentric ways of thinking and making within design.

Saskia Gullstrand

Saskia Gullstrand is a comic artist who creates stories about siblinghood, violence and love. In her work, she explores how montage technique and layout functions as fundaments of comics storytelling. Her role as an artist within research projects is to invite the public into the researchers’ work by interpreting and portraying their ideas as a visual world. She is educated at The Comics School in Malmö.

Li Jönsson

Li Jönsson is a design researcher, Malmö University works in the field of STS, participatory design and speculative design. She has broad experience in making and engages in questions related to how design can open up for alternative ways of understanding, intervening, and expanding issues with a focus to contribute to publics’ experience and engagement with more-than-human worlds.

Kristina Lindström

Kristina Lindström research draws on speculative, participatory, and inventive methods with a focus on how design can cultivate alternative ways of understanding, experiencing, and engaging with climate change amongst publics. She has worked together with Ståhl since 2003. The two set up The Un/Making Studio to explore alternatives to progressivist and anthropocentric ways of thinking and making within design.

References

- Beehive Collective. 2021. “True Cost of Coal – Interview with Beehive Design Collective Members.” Kersplebedeb. https://kersplebedeb.com/posts/true-cost-of-coal-interview-with-beehive-design-collective-members/.

- Beehive Collective. n.d.a. “Beehive Design Collective.” https://beehivecollective.org/.

- Beehive Collective. n.d.b. “The True Cost of Coal.” https://beehivecollective.org/beehive_poster/the-true-cost-of-coal/.

- Beehive Collective. n.d.c. “What We Do.” https://beehivecollective.org/about-the-hive/what-we-do/

- Beehive Collective. n.d.d. “Use Our Graphics.” https://beehivecollective.org/graphics-projects/use-our-graphics/.

- Boehnert, Joanna. 2015. “Ecological Literacy in Design Education. A Theoretical Introduction.” FORMakademisk 8 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.1405.

- Boehnert, Joanna. 2019. “Ecocene Design Economies. Three Ecologies of Systems Transitions.” The Design Journal 22 (sup1): 1735–1745. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595005.

- DiSalvo, Carl. 2022. Design as Democratic Inquiry. Putting Experimental Civics into Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Feola, Guiseppe. 2019. “Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for ‘Other Worlds’..” Progress in Human Geography 32 (5): 613–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508090821

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2008. “Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for ‘Other Worlds’.” Progress in Human Geography 32 (5): 613–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508090821

- Groensteen, Thierry. 2013. Comics and Narration. Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

- Haraway, Donna. 1991. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, edited by Donna Haraway, 149–181. New York: Routledge.

- Haraway, Donna. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services). 2019. “Summary for policymakers of the assessment report of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on pollinators, pollination and food production.” https://www.ipbes.net/sites/default/files/downloads/pdf/ipbes_4_19_annex_ii_spm_pollination_en.pdf.

- Jungnickel, Kat. 2023. “Speculative Sewing: Researching, Reconstructing, and Re-imagining Wearable Technoscience.” Social Studies of Science 53 (1): 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127221119213.

- Jönsson, Li, Kristina, Lindström, and Åsa, Ståhl. 2021. “The Thickening of Futures.” Futures 134: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102850.

- La Cour, Erin, Simon Grennan, and Rik Spanjers. 2022. Key Terms in Comics Studies. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74974-3.

- Law, John. 2004. After Method – Mess in Social Science Research. London and New York: Routledge.

- Leichenko, Robin, and Karen O’Brien. 2020. “Teaching Climate Change in the Anthropocene: An Integrative Approach.” Anthropocene 30: 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2020.100241.

- Leppänen, Katarina, and Therese Svensson. 2016. “Om naturupplevelser hos Elin Wägner och Hagar Olsson. Lästa i eko- och vithetskritisk belysning.” Tidskrift för genusvetenskap 37 (1): 11–31. https://doi.org/10.55870/tgv.v37i1.3139

- Lorenz-Meyer, Dagmar, Pat Treusch, and Xin Liu. 2017. “Feminist Technoecologies: Introduction.” Australian Feminist Studies 32 (94): 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2017.1466654

- Lury, Celia, and Nina Wakeford. 2012. Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social. London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.