Abstract

In this viewpoint paper, we present a conceptual framework for research on art therapy with children/adolescents diagnosed with cancer or blood disorders, their families, and healthcare providers. The framework was developed based on the authors’ extensive clinical experience with the pediatric hematology/oncology population, observations of mechanisms of change through the art therapy process, current literature based on the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual effects of art therapy with the pediatric hematology/oncology population, and identified gaps in research. The purpose of the conceptual framework, referred to as pediatric care and art therapy study (P-CATs) is to serve as a guide for future research studies and to further understand how art therapy serves the pediatric hematology/oncology population, their families, and healthcare providers.

RÉSUMÉ

Dans cet article point de vue, nous présentons un cadre conceptuel pour la recherche sur l’art-thérapie chez les enfants/adolescents atteints de cancer ou de troubles sanguins, leurs familles et les prestataires de soins de santé. Le cadre a été élaboré sur la base de la vaste expérience clinique des auteurs auprès de la population en hématologie/oncologie pédiatrique, de l'observation des mécanismes de changement au cours du processus d'art-thérapie, de la littérature actuelle fondée sur les effets biologiques, psychologiques, sociaux et spirituels de l'art-thérapie avec la population traitée en hématologie/oncologie pédiatrique et des lacunes identifiées dans la recherche. L’objectif du cadre conceptuel, appelé étude de soins pédiatriques et d’art-thérapie (P-CATs), est de guider les recherches futures et de mieux comprendre comment l’art-thérapie sert la population en hématologie/oncologie pédiatrique, leurs familles et les prestataires de soins de santé.

This paper provides a framework for approaches to research on art therapy in pediatric hematology and oncology settings. The epistemological and ontological foundations of this framework lie in pragmatist philosophy that emphasizes the role of research in solving societal problems, aligning theory with lived experience and practice and viewing esthetics as informing everyday experience (Seigfried, Citation1996, p. 21). Given the recognized need for systematic research in the field of art therapy (Kaimal, Citation2017, Citation2019; Kaiser & Deaver, Citation2013), this paper provides a conceptual framework for developing a research agenda within a specific clinical population including identified mechanisms of change, research questions and methodologies to guide short- and long-term studies with the aim of capturing the effects of art therapy in a given setting.

Psychosocial needs of pediatric oncology/hematology patients, families, and healthcare providers

Childhood cancer is rare, however, in the United States, it is the main cause of death by disease in children and adolescents (CDC, n.Citationd.). Pediatric oncology covers a broad age range including children (0-14 years old), adolescents (15-19 years old), and young adults (20-39 years old) (National Cancer Institute at the NIH, Citation2018). Nationally, it is estimated that 11,060 children and 5,000 adolescents will be diagnosed with cancer in 2019 (American Cancer Society, Citation2019). Additionally, recent cancer epidemiology has shown success using pediatric cancer regimens to treat young adults (Stock et al., Citation2019). The National Cancer Institute at NIH (Citation2018) reports that roughly 70,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) are diagnosed with cancer every year.

Advancements in cancer treatment have led to the five-year survival rate for children to increase from 58% in the 1970s to over 80% today (American Cancer Society, Citation2019). According to Siegel, Miller, and Jemal (Citation2018), overall survivorship is currently 83% for children and 84% for adolescents. Though these statistics are promising, cancer treatment is aggressive, and it can cause devastating psychological and/or physical late effects months or years after cancer treatment has terminated (National Cancer Institute at the NIH, Citation2019). Psychosocial support during and after a cancer diagnosis is not only crucial for the patient, but also paramount for the psychological well-being of their parents/caretakers and siblings. Masa'Deh, Collier, and Hall (Citation2012) revealed parents of children with cancer experience higher levels of stress when compared to parents of well-children. Kaplan, Kaal, Bradley, & Alderfer (Citation2013) found that siblings of pediatric cancer patients are at risk of cancer-related stress. Over half of the siblings in the study reported moderate to severe levels of cancer-related post-traumatic stress (PTS) reactions and 22% met full criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Kaplan et al., Citation2013).

Standards of psychosocial practice and care for children with pediatric cancer and their families were released by a working group, the Psychosocial Standards of Care Project for Childhood Cancer (PSCPCC) (Wiener, Kazak, Noll, Patenaude, & Kupst, Citation2015). In a multiyear, multistep process to come to a consensus on evidence and need, five critical areas of concern emerged:

Assessment of child and family well-being and emotional functioning;

Neurocognitive status;

Psychotherapeutic interventions;

School functioning; and

Communication, documentation, and training of psychosocial service providers.

The aim now is for ongoing dialogue among professionals in pediatric oncology care to define recommendations, encourage implementation, and evaluate ongoing work in this field (Wiener et al., Citation2015).

The proposed current approach to research is based on the practice-based research model (Lambert, Citation2013b), where support for psychotherapy practice efficacy emerged out of systematic studies of current practice in clinical settings. Such research serves to improve current clinical treatment practices in real time rather than waiting for efficacy trials to go from theory to practice in applicable ways. Mechanisms or factors of change in psychotherapy have been summarized by Lambert (Citation2013a) as coming from the therapist, therapy procedures, and the client with no one mode or model of psychotherapy showing superiority regarding outcomes. Factors that unilaterally contribute to change, regardless of the therapy modality, fall into three categories: support, learning, and action. Lambert (Citation2013a) does, however, advocate for research in understanding specific factors or mechanisms of change within different modalities of therapy to help better understand which therapies may support different client needs at different times and with different circumstances. This paper seeks to address the gap of limited research on the processes, mechanisms of change, and outcomes of the psychotherapeutic components of art therapy, specifically in pediatric hematology/oncology settings. In addition it provides a timeline for short- and long-term studies that can assess the impact of art therapy on individuals, families, and healthcare communities.

Brief overview of art therapy research with hematology and oncology populations

Art therapists have a long tradition of serving in medical settings and working in adult and pediatric hematology/oncology treatment centers. Studies have shown that art therapy has had a positive impact on patients’ health and well-being. Nainis et al. (Citation2006) found adult oncology patients who took part in art therapy activities experienced statistically significant reduction in cancer symptoms, including pain, tiredness, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, and breathlessness, as well as improved appetite and well-being. It was also reported that 90% of the participants in the study felt that art therapy served as a source of distraction and led the participants to focus on something positive (Nainis et al., Citation2006).

When it comes to reporting symptoms for pediatric patients, self-reports as well as guardian or healthcare professionals’ proxy reports can be used to describe symptoms (Hyslop et al., Citation2018). Children may have a difficult time verbalizing their symptoms to the treatment team. Rollins (Citation2005) found that drawing can be a useful aid in getting direct information from pediatric patients about their illness and symptoms while undergoing cancer treatment. In a study of existential issues in pediatric cancer, Woodgate, West, and Tailor (Citation2014) explored the use of computerized drawings to gain insight into issues around anxiety and distress when facing cancer. Their interpretive, qualitative study found that children’s drawings and interview data revealed themes of existential concerns including worry, vacuum, longing, and growth highlighting the role of existential and spiritual concerns in pediatric oncology care.

Hyslop et al. (Citation2018) conducted a study at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. This study found that pediatric oncology patients’ (ages 4-7) drawings could be used as a tool to communicate their most important symptoms to their treatment teams, as well as lead to an understanding of the emotional burden of the children’s symptoms, the location of pain, and perception of their overall health. Thus, findings could enhance the care that nursing staff and others provide (Hyslop et al., Citation2018). Similarly, Aguilar (Citation2017) conducted a review of studies to look at the effectiveness of art therapy on children living with cancer. Their search revealed seven studies that met criteria for inclusion for the review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Results suggest that art therapy, in the form of drawing interventions, improved communication with family members and providers, served as an expression of feelings, helped children develop effective coping skills, and reduced the negative effects from treatment (Aguilar, Citation2017).

‘Quality of life’ is a term that is often considered in cancer care generally, and in pediatric oncology, as a term that seeks to address ways in which comfort and day-to-day experiences can be observed and supported under stressful circumstances. Although this construct is being studied fairly frequently in adult cancer treatment with regard to the use of creative arts therapies as a supportive therapy (Wiswell et al., Citation2019), fewer studies are looking at this in the pediatric oncology literature. Madden, Mowry, Gao, Cullen, and Foreman (Citation2010) conducted a pilot study that compared six sessions of Creative Art Therapies (two sessions each of art, music, and dance/movement therapy) to the attention of a volunteer to parse out the effects of the therapy on quality of life for children in treatment of ages 2 to 18 years. The study (n = 32) found positive results using a creative arts therapy model (providing music, dance, and art therapies) with a pediatric oncology unit to improve quality of life as measured using the PedsQL 4.0 Cancer module (Varni, Burwinkle, Katz, Meeske, & Dickinson, Citation2002). Madden et al. (Citation2010) added a nonrandomized arm to the same study, which included pediatric hematology, oncology, and bone marrow transplant patients (ages 3-21). It was reported that patients were more excited, happier, and less nervous after participating in a one-hour group creative arts therapy session. Finally, a study conducted in Iraq recently used quality of life as assessed using the KIDSCREEN-10 tool and a randomized control design. The study showed that after a 20-session engagement with art therapy, children improved regarding energy level, relationships, participation in social activities, and perception of school performance (Abdulah & Abdulla, Citation2018).

Though art therapists work at many hospitals across the United States, including leading pediatric hospitals, little has been reported regarding their work, including in pediatric oncology. Of the literature that is available, much comes from pediatric nursing and other practitioners using the tools and techniques of art therapy without having an art therapist as part of the research or treatment team (Aguilar, Citation2017). Three articles were found that were written by art therapists practicing in medical oncology settings and describe the programs and/or processes with pediatric (Ciucci & Heffner-Solimeo, Citation2018; Councill & Ramsey, Citation2019) and adolescent/adult clients (Peterson, Citation2015). It is imperative to identify where art therapists are working within the pediatric hematology/oncology field and identify art therapy practices to begin to support the validity of psychosocial support through art therapy and advocate on behalf of this service.

Tracy’s Kids clinical art therapy model

One approach to clinical research in art therapy is to align researchers with established clinical programs, as seen in the case of Tracy’s Kids (Tracy’s Kids Art Therapy Program, Citation2019) described below. Established art therapy programs have the advantage of having been adapted and refined to meet patient needs within the particular context of care over a long period of time. Research efforts can then map the clinical model, to systematically examine how and to what extent the art therapy program serves patient needs. A well-established clinical model developed over the past two decades is provided by Tracy’s Kids (Citation2019), a nonprofit organization that offers open studio clinical art therapy to patients with cancer and blood disorders, and other chronic, life-threatening illnesses in eight pediatric hematology/oncology settings around the nation. Tracy’s Kids began at the Lombardi Cancer Center of Georgetown University Hospital in 1991 and has grown from one art therapist at one hospital to 10 art therapists at eight locations in five states. In 2018, the Tracy’s Kids programs provided 11,885 art therapy sessions, 24,783 patient contacts, and 895 hours of consultation to medical teams. Since the patients come for medical care, not for psychotherapy, a child-centered, open studio approach was developed that enabled the provision of support during all phases of treatment. The Tracy’s Kids art therapists are integrated members of the medical care team. They educate patients and caregivers about how art therapy can help them cope with the challenges of treatment and also develop personalized treatment plans. Painful medical procedures or devastating diagnoses can feel traumatic and art therapists help the children and families process their experiences and foster greater resilience as they move through treatment. The Tracy’s Kids approach, therefore, embodies many principles of trauma-informed care (Councill & Ramsey, Citation2019) and is a flexible model that can be adapted to different pediatric care sites. The open art studios in outpatient infusion centers, where most young cancer and blood disorder patients receive much of their care, can promote an atmosphere of safety and inclusion, maximize patients’ choices, and provide nonverbal avenues to communicate feelings and needs to the medical team. Collaborative art-making projects in the clinics may reflect the community of support that patients experience in art therapy (see ).

As seen embodied in , art therapists facilitate open studios during clinic hours and invite all patients and caregivers present to participate, normalizing the treatment experience and diminishing the isolation that can be imposed by cancer treatment. Continuity of care is also provided through individual and family support at bedside in the inpatient setting.

Introducing a conceptual framework for research in art therapy

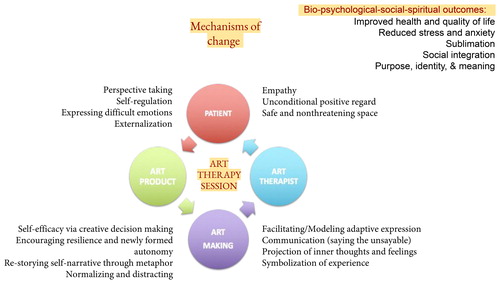

This conceptual framework for research on art therapy in pediatric hematology/oncology settings is founded on clinical observations and anecdotal participant feedback that the services impact the biological, psychological, social, and spiritual/existential aspects of life of the child, family, and care providers. The guiding research question for this framework examines whether and to what extent art therapy can impact the health and psychosocial outcomes of pediatric hematology/oncology patients, families, and healthcare providers. This approach to research is based on the practice-based evidence model (Weisz, Ng, Rutt, Lau, & Masland, Citation2013), where support for psychotherapy practice efficacy emerges out of systematic studies of current practice in typical clinical settings. Practice-based research, such as the current proposed model, looks at improving treatment delivery and systems of supportive care at the clinic level rather than isolating specific variables, which may influence change but do not account for routine practice. Such research models suggest efficacy of particular mechanisms, without accounting for real-time and current experience of patients and practices within service systems. This proposed framework of approaches to research in clinic-based art therapy seeks to use practice-based research to elucidate the effectiveness, or “clinical utility” (Ogles, Citation2013), of art therapy and further articulate the components and related mechanisms of change and expected psychosocial outcomes for participants. Art therapy in a pediatric medical setting has been integrated because it is a child-friendly form of psychosocial support due to its nonverbal, nonintrusive, or assumptive nature relative to other forms of child psychotherapy that have been developed to address mental health or behavioral needs (Aguilar, Citation2017; Councill & Ramsey, Citation2019). Providing an arts-based form of therapy allows for normalization of the hospital experience for a child, which can enable intrapersonal learning and promote a sense of personal agency. Outcomes then focus specifically on the iatrogenic anxiety and stress of the medical experience, which aligns with Ogles’ (Citation2013) conception that outcomes in research will be specific to the setting and need or symptoms addressed by the specific therapy protocol. offers an illustration of how art therapy can promote adaptive responses (Kaimal, Citation2019) among patients, based on the Adaptive Response Theory (ART), a clinical research framework for art therapy.

As can be seen from , art therapy can promote adaptive responses among patients and families undergoing the challenging and stressful experiences of cancer and/or other hematological conditions (Kaimal, Citation2019). There are four components to art therapy practice: the art therapist, the patient, the art-making process, and the art product. Together, these components of the sessions facilitate changes in the patient based on goals including mood, self-efficacy, perceived stress, quality of life, relational development, and adaptive choices in the face of adversity. Based on this clinical approach and mechanisms of change, the proposed research studies in this framework use mixed methods designs and will examine: the mechanisms of change and outcomes of art therapy for patients and families; the impact of art therapy on healthcare providers at the setting; viewer experiences of artwork by patients, families, and care providers; as well as health systems outcomes including reduced healthcare costs and improved medical outcomes such as physiological experiences of fatigue, nausea, and pain.

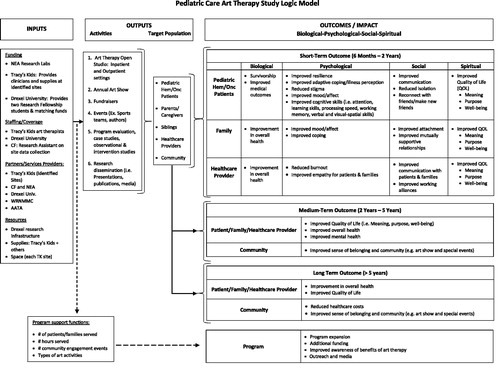

There are several ways to study the processes and outcomes of art therapy with pediatric patients, their families, caregivers, and healthcare systems (see ). We refer to this current set of proposed studies in this conceptual framework as P-CATs (Pediatric Care and Art Therapy Study).

Figure 3. Logic model with approaches to study of processes and outcomes of art therapy with pediatric hematology/oncology patients.

The framework offers several levels of research and analysis from case studies and program evaluations, to observational studies of patient, family, and health systems outcomes, to controlled studies of the impact of art therapy interventions. For short-term studies, we propose clinical case papers describing the range of ways in which art therapy is practiced in pediatric hematology/oncology sites as well as program evaluations to create optimal clinical services. Initial research studies might include case series, feedback on programs, as well as small-N designs (research that uses a small number of participants to track changes within each person with and without the intervention). These illustrative examples can provide comprehensive information on outcomes of the clinical model on children and families, and will be utilized to develop more formal research designs, assessing clinical outcomes across a spectrum of variables. Since the program includes an annual art show, short-term research can also include systematic examination of viewer responses to artwork and the role of the artwork in the therapeutic experience. Responses and feedback can be gathered during annual exhibitions as well as from patients, family members, and healthcare providers on-site and after treatment. Using practice improvement as the rationale, research will incorporate customized forms and standardized measures to evaluate and improve programing in pediatric hematology/oncology units. As a first step at a new site, feedback data can be gathered on prior clinical support before commencing art therapy. Thereafter, offering opportunities for feedback can help gathering data on participant experiences and outcomes resulting from art therapy. Evaluations might also consider using focus groups of caregivers, parents/families, healthcare providers and patients to assess benefits, strengths, and challenges of providing art therapy in cancer care for children.

For studies that can span a longer period of time (2-5 years), there are opportunities for review of clinical documentation and existing electronic health records for retrospective observational analyses. Analysis of quantitative, qualitative, and arts-based data from patients/families who have received art therapy and others who have not can be compared with larger datasets spanning longer periods of time. This can be done with the integration of clinical documentation protocols at selected Tracy’s Kids sites. In addition, targeted interventions may focus on a specific diagnosis or time period of treatment (e.g. survivorship). For example, this could be a research protocol for a family-centered, four-week art therapy intervention to be offered in the survivorship stage. This study design could include a mixed methods approach with quantitative, qualitative, and arts-based data.

Long-term research approaches (e.g. 5-10 years) may examine existing electronic health records to assess impacts on healthcare costs when programs, such as Tracy’s Kids, are introduced in medical sites. Outcomes of interest would be reduced costs of medical procedures, treatment time, and improved health outcomes. Once preliminary studies are completed, larger, fully powered multisite clinical trials could also be initiated to assess the effectiveness of art therapy as a part of the integrative care for pediatric cancer patients.

Data collection, analysis, and dissemination

Data sources for the studies could include qualitative (narrative responses, interview transcripts, and clinical notes), quantitative (standardized self-report measures, parent/caregiver proxy reports, biomarker data), and arts-based (artwork by patients and families, response art by viewers and clinicians ones). Based on clinical observations of how art therapy impacts patients, quantitative measures could include standardized and validated measures of mood, affect, self-efficacy, quality of life, and so on as well as documentation of medications, medical procedures, and art therapy hours. DeWalt et al. (Citation2015) have validated the PROMIS scales for a variety of pediatric chronic health conditions and White (Citation2014) has studied the Perceived Stress Scale for Children for its content validity and reliability. As it pertains to general assessments of quality of life, the PedsQL 3.0 (Janssens, Gorter, Ketelaar, Kramer, & Holtslag, Citation2008) has been found to be valid. In addition, there are several validated scales and measures related to physical, psychological, and spiritual health that would be pertinent to track. Qualitative measures could include interviews, focus groups, and narrative clinical notes. Arts-based data could include visual documentation and descriptions of artwork along with tracking of responses to the artwork and art spaces.

The data gathered above would be analyzed using a range of methods. The quantitative data could first be summarized using descriptive statistics including patient demographics, illness conditions, treatment course, and outcomes. Further inferential statistics will be used to determine relationships between patient characteristics and family responses in the domains of bio-physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions. Qualitative data from interviews, focus groups, feedback, and artwork descriptions will be summarized using case study, grounded theory, and thematic analysis methods. Findings from the studies are expected to be disseminated in academic, community, and practitioner forums to enable widespread access to research on the impacts of art therapy on patient outcomes. The results would be published in scholarly journals as well as in accessible digital media outlets including websites of the collaborating institutions, blog posts, and social media outlets. Some limitations of this framework are that it is based mainly on one clinical approach. Art therapy in other settings might be different and require alternate approaches to research. There might be additional models, research approaches, data sources, and analytic strategies to consider. In addition pediatric hematology and oncology covers a wide age range, which precludes the use of certain standardized measures and approaches.

Conclusions

In this paper, we provided a brief overview of a systematic approach to clinical research in art therapy with pediatric patients diagnosed with cancer and/or hematological conditions, with a conceptual framework called the Pediatric Care Art Therapy Study. A range of mixed methods research approaches that capture the experiences of and impact of art therapy in patients, families, and healthcare providers, as well as healthcare systems, were proposed as part of this framework. Given the need for a systematic approach to research in art therapy, this conceptual framework was created to better understand the impacts and outcomes of art therapy over short- and long-term periods of inquiry in pediatric hematology and oncology settings. Such frameworks could be developed and adapted for application to a range of clinical populations served by art therapists especially in open studio formats.

Disclaimer

The view(s) expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., the National Endowment for the Arts Office of Research & Analysis, or the National Endowment for the Arts, or any other agency of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The National Endowment for the Arts does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information included in this material and is not responsible for any consequences of its use.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdulah, D. M., & Abdulla, B. M. O. (2018). Effectiveness of group art therapy on quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 41, 180–185. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2018.09.020

- Aguilar, B. A. (2017). The efficacy of art therapy in paediatric oncology patients: An integrative literature review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 36, 173–179. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2017.06.015

- American Cancer Society. (2019). Key statistics for childhood cancers. Retrieved August 28, 2019 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-in-children/key-statistics.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (n.d.). Cancer: Picture of America. Retrieved June 24, 2019 from https://www.cdc.gov/pictureofamerica/pdfs/Picture_of_America_Cancer.pdf

- Ciucci, A. C., & Heffner-Solimeo, H. (2018). The next chapter: Altered bookmaking art therapy for caregivers in pediatric oncology/bone marrow transplant. Art Therapy, 35(2), 94–98. doi:10.1080/07421656.2018.1483167

- Councill, T. D., & Ramsey, K. (2019). Art therapy as a psychosocial support in a child’s palliative care. Art Therapy, 36(1), 40. doi:10.1080/07421656.2019.1564644

- DeWalt, D. A., Gross, H. E., Gipson, D. S., Selewski, D. T., DeWitt, E. M., Dampier, C. D., et al. (2015). PROMIS pediatric self-report scales distinguish subgroups of children within and across six common pediatric chronic health conditions. Quality of Life Research, 24(9), 2195–2208. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-0953-3

- Hyslop, S., Sung, L., Stein, E., Dupuis, L. L., Spiegler, B., Vettese, E., et al. (2018). Identifying symptoms using the drawings of 4-7 year olds with cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 36, 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2018.08.004

- Janssens, L., Gorter, J. W., Ketelaar, M., Kramer, W. L. M., & Holtslag, H. R. (2008). Health-related quality-of-life measures for long-term follow-up in children after major trauma. Quality of Life Research, 17(5), 701–713. doi:10.1007/s11136-008-9339-0

- Kaimal, G. (2017). The road ahead: Preparing for the future of art therapy research. In R. Carolan and A. Backos (Eds.), Emerging perspectives in art therapy: Trends, movements and developments (pp. 58–74). New York: Routledge.

- Kaimal, G. (2019). Adaptive Response Theory (ART): A clinical research framework for art therapy. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association. doi:10.1080/07421656.2019.1667670

- Kaiser, D. H., & Deaver, S. (2013). Establishing a research agenda for art therapy: A Delphi study. Art Therapy, 30(3), 114–121. doi:10.1080/07421656.2013.819281

- Kaplan, L. M., Kaal, K. J., Bradley, L., & Alderfer, M. A. (2013). Cancer-related traumatic stress reactions in siblings of children with cancer. Families, Systems, & Health, 31(2), 205–217. doi:10.1037/a0032550

- Lambert, M. J. (2013a). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychotherapy. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 169–218). New York: Wiley.

- Lambert, M. J. (2013b). Introduction and Historical Overview. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 169–218). New York: Wiley.

- Madden, J. R., Mowry, P., Gao, D., Cullen, P. M., & Foreman, N. (2010). Creative arts therapy improves quality of life for pediatric brain tumor patients receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 27, 133–145. doi:10.1177/1043454209355452

- Masa'Deh, R., Collier, J., & Hall, C. (2012). Parental stress when caring for a child with cancer in Jordan: A cross-sectional survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10(1), 88–88. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-10-88

- Nainis, N., Paice, J. A., Ratner, J., Wirth, J. H., Lai, J., & Shott, S. (2006). Relieving symptoms in cancer: Innovative use of art therapy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 31(2), 162–169. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.006

- Ogles, B. (2013). Measuring change in psychotherapy research. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 134–166). New York: Wiley.

- National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2018). Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Retrieved August 30, 2019 from https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya

- National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2019). Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer (PDQ®)-Patient Version. Retrieved June 24, 2019 from https://www.cancer.gov/types/childhood-cancers/late-effects-pdq#_387

- Peterson, C. (2015). Walkabout: Looking in, looking out”: A mindfulness-based art therapy program. Art Therapy, 32(2), 78–82. doi:10.1080/07421656.2015.1028008

- Rollins, J. A. (2005). Tell me about it: Drawing as a communication tool for children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 22(4), 203–221. doi:10.1177/1043454205277103

- Seigfried, C. H. (1996). Pragmatism and feminism: Reweaving the social fabric. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., & Jemal, A. (2018). Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(1), 7–30. doi:10.3322/caac.21442

- Stock, W., Luger, S. M., Advani, A. S., Yin, J., Harvey, R. C., Mullighan, C. G., et al. (2019). A pediatric regimen for older adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of CALGB 10403. Blood, 133(14), 1548–1559. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-10-881961

- Tracy’s Kids Art Therapy Program. (2019). Tracy’s Kids about us. Retrieved from http://www.tracyskids.org/about-us/

- Varni, J. W., Burwinkle, T. M., Katz, E. R., Meeske, K., & Dickinson, P. (2002). The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer, 94(7), 2090–2106. doi:10.1002/cncr.10428

- Weisz, J. R., Ng, M. Y., Rutt, C., Lau, N., & Masland, S. (2013). Psychotherapy for children and adolescents. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 541–585). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- White, B. P. (2014). The perceived stress scale for children: A pilot study in a sample of 153 children. International Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health, 2(2), 45–52. doi:10.12974/2311-8687.2014.02.02.4

- Wiener, L., Kazak, A. E., Noll, R. B., Patenaude, A. F., & Kupst, M. J. (2015). Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: An introduction to the special issue. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62(S5), S419–S424. doi:10.1002/pbc.25675

- Wiswell, S., Bell, J. G., McHale, J., Elliott, J. O., Rath, K., & Clements, A. (2019). The effect of art therapy on the quality of life in patients with a gynecologic cancer receiving chemotherapy. Gynecologic Oncology, 152(2), 334–338. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.11.026

- Woodgate, R. L., West, C. H., & Tailor, K. (2014). Existential anxiety and growth: An exploration of computerized drawings and perspectives of children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 37(2), 146–159. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31829ed29