ABSTRACT

This study examines positive low- and high-grade assessments in service encounters between customers and salespersons conducted in Swedish and recorded in Sweden and Finland. The assessments occur in a regular sequential pattern as third-turn moves that complete request-delivery sequences, longer coherent requesting sections, or request sequences in a pre-closing context. The positive valence of the assessments coheres with the satisfactory outcome of task completion, but their function is primarily pragmatic, used for segmenting the flow of task-oriented institutional interaction. The assessments stand as lexical TCUs, and their delivery is characterized by downgraded prosody and the speaker’s embodied shift away from the other. The analysis reveals distributional differences in the interactional practice: Customers produce task-completing assessments more often than the salespersons, and high-grade assessments are more frequent in the data from Sweden than from Finland. The data are in Sweden Swedish and Finland Swedish with English translations.

Assessing has been found to be a social activity that displays characteristic patterns of sequential organization and is connected to the more overarching social principle of preference organization (e.g., Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1987; Pomerantz, Citation1984), but assessing is also linked to factors like epistemic stance and agency (see, e.g., Heritage & Raymond, Citation2005; Thompson, Fox, & Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2015, p. 144). The study we report on here contributes to the body of work on assessing in social interaction by taking a specific type of institutional activity to the foreground: service encounters in a commercial setting (see, e.g., Felix-Brasdefer, Citation2015; Fox, Citation2015). In such interactions, both customers and salespersons engage in the exchange of information, delivery of goods, and other services. The customer wants to buy a product or receive information related to the product, and the staff requests relevant documents and payment at certain stages of the commercial exchange. The participants also position themselves relative to one another in displaying shared understanding, agreement, and orientation to their differential rights and obligations in the asymmetrical institutional context.

We have specifically investigated the social organization of box office encounters in Swedish and observe a recurrent sequential pattern around different forms of task completions in these activities. A typical sequential trajectory hereby involves (a) a (general) requesting action, (b) delivery of the requested service, and (c) a positive assessment by the requester at the completion of the task. Extract 1 illustrates the organization of such a sequence; the turns in analytic focus are bolded and flagged with descriptive labels in the right margin, and the assessment turn is highlighted.

In line 5 the customer makes an initial request (see Fox, Citation2015) by asking for the availability of tickets for a certain show, upon which she receives confirmation, which in this type of institutional encounter stands for the delivery of (one kind of) relevant service item. In a third turn of the exchange (line 8), the customer provides a positive assessment, the adjectival phrase bra (“good”). Because assessments of this kind mark the completion of a task-oriented sequence, generally working as sequence-closing thirds (Schegloff, Citation2007), we hereafter refer to them with the label task-completing assessments (TCAs). The assessment in line 8 is followed by a move to the next task, a query about the location of the show, which in effect manifests the completion of the prior sequence.

We examine the sequential progression leading up to task-completing assessments, their vocal and embodied features, and their general distribution in interactions between customers and salespersons. In identitying the sequence-initiating moves, we use the term request (or requesting) in a broad manner, referring to any type of utterance through which one of the participants asks the other to do something for him- or herself (see Drew & Couper Kuhlen, Citation2018, on requesting in general). This includes soliciting information, requesting a physical object (like a booking document) or an action (like payment). This rather generic approach to requesting follows from the nature of the data: There is a strong normative expectation of hearing the customer’s utterances as requests in the context of service encounters, which are characterized by institutional task orientation (see Lindström, Citation2005; also Fox, Citation2015); by taking an inclusive rather than restrictive approach to what might function as requesting we then were able to do more justice to what is going on in our service encounters.

Task-completing assessments are nonclausal items, usually consisting of a single lexical item as in Extract 1. The assessments are also on a positive evaluative scale but vary in intensity between low-grade (more moderate) items, e.g., bra (“good”) and high-grade (more intensive) items, e.g., perfekt (“perfect”). Low-grade assessments are typically constituted of adjectives in the positive degree; such items can easily be upgraded by different means, e.g., bra (“good”) > jättebra (“super good”). Low-grade items are also typically topped by more high-grade ones in second assessments (Pomerantz, Citation1984; for Scandinavian, see Lindström & Heinemann, Citation2009). As regards the variation on a scale of intensity, we compare the use in the two national varieties of Swedish, Sweden Swedish, and Finland Swedish, in order to document whether there are cultural differences in the interactional metric.

The article is organized as follows: First, we give a short overview of prior research on assessments in talk-in-interaction and its relation to the assessments in our focus. We then present our data and principles for making our collection of cases. This is followed by an analysis that focuses on TCAs in local requesting sequences and in pre-closing environments. Finally, we discuss the distribution of assessments in our data sets and what that can say about possible cultural preferences for the assessment practice in question.

Background

There is a rich body of research on assessments within the tradition of Conversation Analysis, dating back to the seminal work by Pomerantz, who, in a series of publications (see, e.g., Citation1978, Citation1984), demonstrated that assessments are sequentially organized social actions.Footnote1 Her data were sourced from everyday interactions where participants, for example, reported on their experiences of past events and activities, and in particular, she focused on second assessments produced by recipients in response to initial assessments in the prior turn. She showed that upgraded second assessments were produced regularly in this slot and suggested that they functioned as a means of displaying alignment with the initial assessment. Based on video data, Goodwin and Goodwin (e.g., C. Goodwin, Citation1984, Citation1986; Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1987, Citation1992a) took into account also how interlocutors use embodied resources (e.g., gaze, body orientation, gestures) to coordinate assessments—for example, through head nods or facial expressions—and argued for an integrated analysis of verbal, prosodic, and embodied resources to account for how assessments emerge in interaction. More recently, Thompson et al. (Citation2015, ch. 4) have broadened the study of responsive assessments (including second assessments) to encompass aspects of grammatical formats (e.g., phrasal/clausal) and different functional facets of responsivity (e.g., epistemic access, agency).Footnote2 All these studies have been based mostly on everyday talk.

Assessments have been studied also in institutional environments. Early work includes assessments in classroom interaction, where a tripartite turn structure of initiation–reply–evaluation (IRE) has been shown to be a powerful organizational feature (Macbeth, Citation2003; Mehan, Citation1979). More in resonance with our study, Antaki, Houtkoop-Steenstra, and Rapley (Citation2000) have examined responsive assessments in interviews between psychologists and respondents. These interviews contained characteristic uses of phrasal positive high-grade assessments, such as brilliant, smashing, terrific. The study shows that the assessments are task oriented rather than content oriented in that they are regularly used by the professional to terminate question–answer sequences or longer courses of agenda-driven action, like going through a page in a questionnaire, and are followed by a move to the next point on the agenda. The use of these assessments is indicative of institutional talk and marks a display of control of the interactional sequence (see Antaki, Citation2002). Also Lindström and Heinemann (Citation2009) suggest that assessments are a typical feature of institutional interaction in evaluations of task outcome. Their study of Danish and Swedish caregiving situations shows that low-grade assessments such as godt and bra (“good”) are used by the recipients of care as a means of signaling acceptance of the institutional party’s task completion. The authors argue that a low-grade evaluation is treated as sufficient because the caregivers are institutionally obliged to perform their tasks. On the contrary, high-grade items are used in their data when caregivers praise the elderly care recipients for managing tasks that are difficult for them, i.e., successful task completion is treated as a major accomplishment in such cases.

Similar to the studies by Antaki et al. (Citation2000) and Lindström and Heinemann (Citation2009), our analysis concerns a specific type of responsive assessments: They occur as the last element in a three-partite action sequence, as shown in Extract 1. Accordingly, it can be argued that the general function of these assessments is to signal the acceptance of a successful institutional service delivery and the completion of a section in a task-oriented activity. Such assessing practices are very different from other types of assessments that may occur in everyday conversations, such as supporting actions to a telling (see Thompson et al., Citation2015, p. 200).

Data and collection

The data for the present study consist of 426 video-recorded interactions drawn from a larger corpus of 1,300 service encounters collected in Sweden and Finland for the binational research program Interaction and Variation in Pluricentric Languages.Footnote3 The program compares pragmatic and interactional patterns in the two national varieties of Swedish, i.e., Finland Swedish and Sweden Swedish. The data for the present study come from four venues (theater box offices or ticket booking agencies) in each country, at three different sites: the capital city, the second city, and a regional city. We found in total 296 task-completing assessments in the 426 encounters, which then constitute the core collection for our analysis. The data were collected with the informed consent of those involved, giving us also the permission to cite fragments of the transcripts and visuals as reproduced in this study.

All interactions took place between a customer and a member of staff and concerned ticket purchases or the collection of prebooked tickets and in some cases information about tickets and shows. In these data, we noted that certain phrasal positive assessments, such as bra (“good”), toppen (lit. “the top,” “super”) and perfekt (“perfect”), occurred with a steady frequency in task-completing sequential slots, constituting turn-constructional units of their own. Assessments with a clausal form were instead used in contexts where the participants commented on the literal contents of an informing, as can be seen in the assessment in line 3 in the following:

The salesperson states the cost of purchase, whereupon the customer indicates willingness to pay with the exact sum in cash (searching for a 10 crona coin), which can be seen as an initiation of an insertion sequence. The salesperson produces a next turn in the insertion sequence, the appreciating evaluation de vore jättebra (“that would be super good”), which has a full clausal form. This then is not a task-completing assessment but an assessment of the customer’s willingness to make the payment (and complete the actual task) in a certain way. The task of doing the payment and the completion of the sequence is accomplished in lines 4–5, and it is in this slot that the salesperson produces a phrasal high-grade assessment (perfekt).

The typical sequential position for the task-completing assessment is a third turn, following a request–compliance exchange, as shown in Extract 1. In addition, TCAs also occur in the final sequences of service encounters when a request–compliance exchange is nested in pre-closing activities, just preceding the ritual closing (thanking, leave taking) of the interaction; for examples and analysis, see Extracts 8 and 9.

Task-completing assessments are a regular feature of the encounters in our data, and they occur with a basically similar frequency across the national varieties, but there is some notable variation in the distribution of assessment forms, which is a question we will return to in the section “On the distribution of assessments in the data sets.” Assessing a task completion is typical customer behavior in our data, but salespersons also produce TCAs. Both low- and high-grade assessments occur in the context of all three types of errands: on-site purchase of tickets or the collection of prebooked tickets and queries about tickets or shows. TCAs, though ubiquitous in the data, are not produced in every single encounter or task-completing slot. There is a number of successful task completions that are receipted with a nonevaluative item, like ja (“yeah”) or okej (“okay”) in a third turn. In other cases, an expression of gratitude seems to cover the function of closing a successful task sequence, typically in payment and ticket delivery sequences. Moreover, the outcome of the local task sequence may be negative; for example, the salesperson replies to the customer’s request of tickets that none are available. In such cases the third turn consists of a news-receipt token, aha (“I see”) or oj (“oh [dear]”), or the acknowledging okej, as in the following case:

The customer has requested tickets for a show on the same day, and in line 1 the salesperson informs her that the popular show named Grottmannen (“The Cave Man”) is sold out. The customer receipts this with a turn initiated with okej followed by a repetition of the negative content. The salesperson confirms by repeating that the show is sold out, whereupon the customer closes the sequence with an o:kej and then adds a final thanks in line 5. A positive assessing token, like bra (“good”), would not be possible in such cases, since positive assessments respond to a satisfactory outome from the requester’s perspective. In our current analysis, we focus only on the use of positive evaluative items (and thus sequences with a positive outcome) and regularities and variation in their use; this leaves out nonevaluative particle receipts like ja and okej, which would warrant a study of their own in activity transitions (see, e.g., Keevallik, Citation2010).

Analysis

In the following we examine the interactional progression and environments in which the task-completing assessments occur in our data. The section “Third-turn assessments at the completion of task sections” presents four extracts illustrating third-turn assessments at the completion of separate task sections in an encounter that has not reached a point of potential closure. The section “Third-turn assessments in pre-closings” presents two extracts that are produced in the pre-closing sequences of service encounters where they provide a lead-in to the closure of the whole encounter.

Third-turn assessments at the completion of task sections

Extract 1 illustrated a task-completing assessment (bra [“good”]) in a receipting third turn produced by the customer after delivery of the requested information (i.e., acknowledgement by the staff that there are seats available). In the following we show a longer extract from the same interaction, which includes the case in Extract 1, lines 5–8, and the continuation of the sequence containing another tripartite series of request–delivery–assessment in lines 14–19. The relevant turns for the analyses are bolded in all extracts, and the assessments are also highlighted:

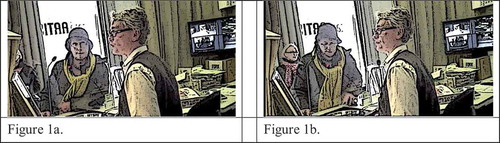

Extract 4 illustrates a case where the customer engages in a series of requests of information. After having established that the play is performed the same evening (lines 2–4), the customer inquires about ticket availability (line 5). Upon receiving a short affirmative response from the staff (line 6), the customer receipts this information by a positive assessment, bra (“good”) in line 8. It ratifies the acceptable completion of this initial task. The assessment is uttered quickly and with a low volume, and immediately after a micropause the customer launches her next request (line 11): e de på nån liten scen (“is it at some small stage?”). The staff delivers a response (line 12), which the customer, in overlap, receipts with an affirmative jå (“yes”) before issuing her next request of information dealing with the show, formulated as two statements in quick succession, still partly in overlap with the salesperson’s turn (lines 14–16): å de e klockan sju å den tar en dryg timme e de så (“and it’s at seven o’clock and it goes on for a little over an hour, is that right?”). The final “is that right?” invites confirmation, and in line 17 the staff verifies the duration of the play through exact repetition (“it goes on for a little over an hour”) before adding some new information: å så brukar de vara en liten diskussion efteråt (“and there is usually a small discussion afterwards”). The customer receipts this with a high-grade assessment (utmärkt [“excellent”]) produced distinctly but fast-paced and in overlap with the end of the prior turn (line 19) at the same time as she changes body posture. The customer has been leaning toward the counter with her left arm, gazing directly toward the salesperson (, line 9); just after having uttered the TCA utmärkt (“excellent”), she straightens her position and moves her head and gaze away from her interlocutor to the counter () where she starts handling her wallet, taking out a credit card (line 20). The high-grade item utmärkt and the ensuing embodied practices signal that a certain section in the interaction has been completed: The initial conditions for advancing to ticket purchase have been clarified, and in this sense, the initial information-seeking requests may be considered pre-requesting practices (see Levinson, Citation1983, p. 356; Schegloff, Citation2007, pp. 90–91; also Rossi, Citation2015). Subsequently, the customer moves on to introduce a new issue, a payment-related query (line 21), indicating that she is moving on to make a purchase.

We argue that the main function of utmärkt (“excellent”) is to close the successful initial section of the encounter and imply a move to a next set of tasks, rather than to literally comment on the contents of the new information of the prior turn, i.e., that there usually is a discussion after the play. There are several indices that support this analysis: The evaluative item appears on its own, rather than as part of a full clausal expression; it is produced partially in overlap with the unsolicited extra information (about the final discussion) and in a fast tempo; the customer also directs her gaze away from the interlocutor toward the counter simultaneously straightening her standing position from an earlier slightly forward-leaning position. The embodied practices thus show that the customer is oriented to doing transitional work at the closure of the sequence. She then starts handling her wallet, which embodies a move away from the current task and a shift to “doing business” proper (see Halonen & Koivisto, Citationin press on money as an interactional resource in service encounters).

Comparing the two assessment turns in this extract, there is a notable difference in the intensity of the lexical expression, from low-grade bra (“good”) in the first instance, to high-grade utmärkt (“excellent”) in the section-closing case. We argue that the high-grade item is more readily hearable as the definitive closure of a task section with some internal coherence,Footnote4 in this case dealing with the initial contingencies of requesting a ticket, whereas the low grade item bra signifies the completion of a subtask in the section, the initial request about ticket availability. This kind of “portioning” of intensity grades is discernable also in Extract 5, here in the realm of one sequence, in which the salesperson is delivering two sets of requested tickets, one set to the matinée show of a musical, another set to the evening show:

The service delivery takes place in lines 1–2 accompanied with the salesperson pointing out that indeed there are two different sets of tickets as requested (line 3), which is receipted by the customer with partial repetition (olika [“different”]) and a potentially task-completing assessment bra (“good”). However, the salesperson adds a further explication in line 5, making sure that the customer notices that the start of the other show is in the evening, at 7 p.m. The customer registersFootnote5 again with partial repetition (klockan nitton [“at nineteen hours”]) and concludes with an upgraded TCA, utmärkt (“excellent”). Also here, the high-grade item marks the definitive closure of a successful task section with some internal coherence. Another variation of this principle is found in cases where a first request-delivery pair is closed with an acknowledging particle (ja [“yes”] or okej [“okay”]) and the section-closing one with a positive assessment, either in low or high grade. However, we cannot say that upgrading in a series of request-delivery sequences is a definitive normative principle in the data: There is variation in speaker conduct and probably in the sense to what degree a series of sequences is experienced as a coherent project consisting of subtasks; moreover, if the speaker uses a high-grade assessment in the first place, there is no room for any upgrading in latter sequences.

As discussed previously, Lindström (Citation2005) and Fox (Citation2015) point out that there is a strong normative expectation in service encounters of treating all kinds of requesting utterances as requests proper, which makes a distinction between requests and pre-requests complicated. It can be argued that the initial request in Extract 4 concerning ticket availability is a form of a pre-request, as it deals with contingencies in the request, i.e., availability. However, a similar kind of initial request can be treated as the request, as is shown in Extract 6.

The customer uses the same existential request-of-information form (finns de biljetter [“are there tickets”]) as in Extract 4. The service item in the local sequence is the salesperson’s positive answer jå (“yes”), which the customer receipts with the sequence-closing assessment nice, a slangy loan from English. The salesperson treats the initial request of information and the ensuing positive assessment as an initiation of ticket purchase and starts to progress the order in line 9 by asking how many tickets the customer wishes to buy.

Our final example (Extract 7) in this section illustrates how a task-completing assessment is produced by the salesperson.

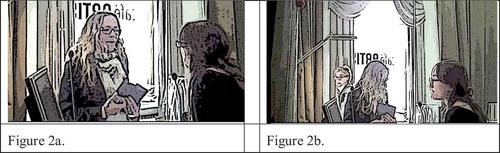

In Excerpt 7 the customer is picking up three preordered tickets giving a last name as a booking reference (line 2) and further specifying the booking by giving the date (line 8). The staff proceeds to locate the tickets in the booking system (line 9), and then requests acknowledgement of the type of tickets (lines 13–14, ). The customer confirms, and the staff then receipts this with bra (“good”), uttered quickly and in a low, high-pitched voice just as she has turned her head back to the computer screen (lines 16–17, ). The assessment and the bodily behavior signal the successful completion of the task section (dealing with the retrieval and type of tickets), rather than referring to the literal content of the customer’s negating turn in line 15, i.e., that it is “good” that the purchase concerns regular rather than discounted tickets (which could be in the interest of the commercial agent). Following a brief pause, while oriented to the screen, the salesperson then verbally initiates the next task, the payment.

Figure 2. (a) S is leaning forward and gazing at C. (b) S is oriented to the computer screen, C gaze down (left).

In general, the salespersons assess the outcome of service events more seldom than the customers (see further the section “On the distribution of assessments in the data sets”). This suggests that there is a difference in the assessment behavior that has to do with the institutional roles but also with the kinds of tasks associated with those roles: The customers are expected to carry out certain routines, such as payment or confirming booking information like in Extract 7, i.e., actions that are part and parcel of the commercial transaction and the completion of which is often receipted with ritual thanking. The salespersons are obliged to serve the customers, but their ability to deliver a requested item is more contingent on variable circumstances such as the availability of tickets, preferred dates, or good seats. A successful completion of such service tasks may thus more readily warrant an appreciating ratification from the customer, as in Extract 6.

The assessments discussed previously are all third-turn receipts that appear in a sequential tripartite environment of request–delivery–receipt. In addition, these sequences pattern around certain junctures in the task-oriented encounters: completing a sequence that paves the way for placing or progressing the order (Extracts 4, 6), completing a sequence that enables the delivery of the central requested item, i.e., the tickets (Extract 7), or completing the delivcery of the central requested item (Extract 5). It is noteworthy that the assessments are not followed by a comment by the interlocutor; rather, the interlocutors orient to them as boundary markers. In such a segmenting function, TCAs facilitate a transition to the next institutional task, introduced by either party. The assessments thus contribute to maintaining intersubjectivity, i.e., the participants’ mutual orientation to and shared understanding of the courses of interactional trajectories (cf. Schuetz, Citation1953).

Common to TCAs is also their downgraded prosody—generally uttered in a fast tempo and in a low volume—which does not match their positive lexical content and sometimes intensive degree. This resonates with Antaki et al. (Citation2000), who observe that closure-oriented high-grade assessesments in client-therapist interactions were delivered in a “truncated” manner (contracted, sotto voce, sped up). We also note that a similar kind of mismatch between content and prosody is reported by Ogden (Citation2006) for lexically upgraded second assessments, which can be prosodically downgraded in environments where they preface dispreferred actions. Instead of dispreference, the examples analysed perviously suggest that the downgraded prosodic qualities of TCAs have to do with their pragmatic segmenting function. Further, they are accompanied by embodied features that signal sequence completion and an orientation toward transition to a new task, usually through averted gaze (see Streeck, Citation2014) and bodily shift away from the other (see LeBaron & Jones, Citation2002). Bodily movements are thus used as a meaning-making resource for segmenting and organizing the service encounter (cf. Sorjonen & Raevaara, Citation2014).

In contrast to the results in Lindström and Heinemann (Citation2009), there is no general tendency to avoid high-grade assessments in our data. However, the use of low- and high-grade items is patterned in some respects, according to the position in an exchange (upgrading in subsequent position as in Extracts 4 and 5) and language variety (see the section “On the distribution of assessments in the data sets”). The customers assess more often than the salespersons, but there is no significant other difference in the assessing practice that could be related to participant roles. As noted by Antaki et al. (Citation2000) and Antaki (Citation2002), assessing is indicative of who has control of the local sequence, or to put it differently, who has the communicative entitlement to assess and judge when a section of the interaction is completed (see Myers, Citation2000; also Rhys, Citation2016). These assessor rights shift in our data depending on who has initiated the sequence. On the one hand, there are fulfillments of tasks that are beneficial for the customer who then is entitled to accept and assess their delivery (e.g., of tickets in Extract 5); on the other hand, there are acts, like the customer’s decision to conclude a purchase (Extract 7), that are beneficial for the salespersons in their position as representatives of the service provider and who then, through a positive assessing token, may mark the accomplishment of an “official” section in the exchange.

Third-turn assessments in pre-closings

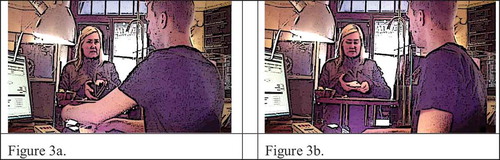

We now proceed to discuss task-completing assessments that occur in closure-oriented environments in the trajectory of a service encounter. Not all service encounters end with the completion of the formal commercial transaction, although the payment sequence has all the practical potential of being a closing-implicative action. Instead, the customers often wrap up the possible closure after the payment with an additional request of information that typically concerns the duration of the show, a possible interval, or the location of the stage. When this final, wrap-up request has been dealt with, the requester (customer) produces a task-completing assessment, which thus inhabits a local third-turn position. Extract 8 provides an example of the practice. The customer has bought tickets to a certain show, and the payment episode is carried out in lines 1–12, ending with a possible move to a closing through the thanking sequence in lines 11–12. However, in line 14 the customer introduces a question about a possible interval (). The supplementary nature of this query is indicated by the turn-prefacing additive conjunction å (“and”)Footnote6 (å blir de nån paus emellan eller [“and will there be an interval in between or”]).

The salesperson delivers a response to the request of information in lines 15–16, and the customer receipts with a TCA, the high-grade item jättebra (“super good”) in line 17, . Such expansions that follow the completion of the payment and the ensuing thanking sequences can be understood as orientations to the closure proper. This closure-oriented sequence then is ratified and recompleted (see Hoey, Citation2017) by the salesperson with an mm (“uhum”) in line 18. Finally, the interactants move to the closing proper, which in Extract 8 consists of paired thanking actions (line 19–20), a very typical form of an encounter-closing adjancency pair in Swedish (see Grahn, Citation2017).

In the trajectory of a service encounter, TCAs of the kind in Extract 8 can be considered having a dual function: They accept the local task-completion as well as the completion of the whole institutional exchange.Footnote7 The evaluative side of these assessments is present, but its target is less obvious. It is hardly likely that the customer in Extract 8 means that it is “super good” that the show has an interval of 35 minutes; rather, by saying jättebra she accepts the information and ratifies a satisfactory completion of the task-oriented interaction as a whole. In other words, the assessment surely shows an orientation to the outcome of the sequence (or encounter) but not so much to the exact contents in the prior turn. This orientation to pragmatic segmentation rather than to literal content is reflected in the downgraded prosody of the high-grade item jättebra and the bodily conduct. When delivering the assessment in line 17, the customer averts gaze and looks down at her wallet on the counter (), sliding a credit card into it, which effectively marks sequence completion (see Streeck, Citation2014) as well as termination of the whole business.

A parallel case from the final sequences of an encounter can be seen in Extract 9. The service encounter has reached a possible end through the completed payment sequence in lines 1–11. Like in Extract 8, the customer then initiates an unwrapping sequence (line 12), this time concerning the location of the stage for the show in question. The additional nature of this inquiry is again signaled with the turn-prefacing conjunction och (“and”).

The salesperson responds with an informing in a full clausal format (de e lilla scenen [“it’s the small stage”]) and adds some further information on the show’s commencement and duration (line 15). This additional information was not requested by the customer, but its potential need was projectable for the salesperson who recurrently receives queries of this kind in this particular, closure-prefacing slot. Upon the information delivery, the customer first produces the receipt token ja (“yes”) (line 16). During the ensuing pause of 0.6 seconds, the salesperson hands over the receipt and ticket, after which the customer produces the high-grade TCA lysande (“splendid”) (line 18) in fast tempo and low volume. At the same time, he lowers his gaze to the counter and handles the documents he has received. As in Extract 8, the possibly pre-closing sequence is recompleted with the salesperson’s mm (“uhum”) in line 19. The closure proper is realized through paired, ritual thanking and leave-taking actions.

To sum up, pre-closing activities at the end of service encounters provide one characteristic interactional locus for task-completing assessments. The typical interactional trajectory involves (a) a wrap-up query by the customer, (b) the salesperson’s completion of the task, (c) the customer’s positive assessment, and (d) the recompletion by the salesperson. Such pre-closing TCAs coordinate the participants’ mutual exit from the interaction by offering a lead-in to the closing proper at the end of extended sequences of action (See Levinson, Citation1983, p. 346; Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1987; Mondada, Citation2009). In the pre-closing environment, task-completing assessments play a dual role: They mark a successful completion of the whole institutional encounter but are at the same time nested in a final request–compliance sequence. Also in these final interactional slots, TCAs vary in intensity between low- and high-grade items, which suggests that speakers have different orientations to the available interactional metric. Nonetheless, the primary function of these assessments is to mark a boundary in the course of a task-oriented exchange rather than to praise the task completion as a major achievement. The weakened literal content is reflected in the downgraded prosody of the positively evaluating item, irrespective of its degree of intensity, and the speaker’s embodied shift away from the coparticipant. Given their status of complex actions and their multimodal composition in meaning making, TCAs then carry features of complex multimodal gestalts (see Mondada, Citation2014) that can only be accounted for in an integrated analysis of verbal, prosodic, and embodied resources (cf. Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1992b).

On the distribution of assessments in the data sets

The previous examples have provided representative cases of the sequential progressions involving task-completing assessments in the data. As regards the sequential order, the use of TCAs patterns in similar ways in our data sets from Sweden and Finland. The assessments are regularly deployed in third-turn receipts at sequence/section completions and in pre-closing environments, they are produced in a prosodically downgraded manner, and the concomitant embodied practices display the same kind of low-key behavior. Neither are there any significant differences in the assessments’ general quantitative distribution between the national varieties of Swedish. Yet we have noticed some striking distributional differences in the intensity of TCAs that are used in the two varieties of Swedish and also some distributional differences that can be related to the speaker roles. provides a summary of the assessment distribution in these respects.Footnote8

Table 1. Distribution of low-grade assessments (LGA) and high-grade assessments (HGA) among the customers and salespersons in the Sweden-Swedish and Finland-Swedish service encounters.a

Common to both national varieties is that customers produce task-completing assessments more often than the salespersons. It is true that customers more often tend to initiate task sequences because they usually have different minor requests during an encounter, but the distribution also says something about the speaker roles. At some of the venues, there were practically no TCAs produced by the staff, although customers used them frequently. Another observation is that there seem to be somewhat more assessments in the data from Finland. However, this difference is probably contingent on circumstantial factors and caused by one of the venues studied (a Helsinki box office) in which assessments were very frequent; the other venues displayed more even frequencies across the data sets. But most importantly, the overwhelming difference between the varieties concerns the assessments’ grade of intensity: Both Sweden-Swedish customers and salespersons use more high-grade assessments than low-grade assessments, whereas the preferences are totally the opposite among the Finland-Swedish participants. Clearly, the speakers in Sweden and Finland respectively operate with a different interactional metric for the same pragmatic function, that of doing task-completing assessments.

As regards lexical qualities, there is a core of evaluative items that is used in our data from both varieties, involving both low-grade (bra [“good”], fint [“fine”]) and high-grade items (utmärkt [“excellent”], jättebra [“super good”], jättefint [“super fine”], perfekt [“perfect”], toppen [“super”]). These all constitute lexical turn constructional units in their interactional slots. In addition, there are some positive high-grade assessments that only occur in the Sweden-Swedish interactions we have studied: kanon (“smashing”), lysande (“splendid”), strålande (“brilliant”), suveränt (“super”), underbart (“wonderful”), fantastiskt (“fantastic”), härligt (“lovely”), grymt (“awesome”). This suggests that the available set of expressions for this pragmatic function not only covers a different end of the assessment scale but is also lexically broader in Sweden Swedish than in Finland Swedish.

The difference in speaker conduct can be related to the “evolved sets of practices” in the two sociocultural settings (see Levinson, Citation2013, p. 124), reflecting the speakers’ enculturation (see Berry, Citation2015, p. 525). We can link this finding to previous studies that suggest that Sweden-Swedish communicative patterns favor markers of a higher degree of interpersonal engagement than those used by speakers of Finland Swedish (see Saari, Citation1995), regarding, for example, terms of address (Norrby, Wide, Nilsson, & Lindström, Citation2015), greetings (Nilsson, Norrthon, Lindström, & Wide, Citation2018), thanking (Grahn, Citation2017), and formulation of feedback (Henricson & Nelson, Citation2017). It seems that the speakers in Sweden more often mobilize the high end of the assessment scale to produce something that is more readily hearable as a token of interpersonal appreciation and rapportFootnote9 —that is, we are witnessing culturally bound linguistic differences in the social positioning of self vis-à-vis other (see Beeching, Ghezzi, & Molinelli, Citation2018, for the linguistic indexing of positioning; also Norrby, Wide, Nilsson, & Lindström, Citation2018). At the same time, the speakers’ assessing conduct is task oriented, unmarked, and routinized in both national speech communities—as evidenced by the prosodic and embodied cues. This result leads us to the conclusion that the assessment grade matters, but not at the level of microanalytically accessible phenomena like the speaker role or the type of the accomplished task or even the type of interactional juncture, although we noted some tendencies for upgrading in the closure of longer task sections. The robust distributional difference in assessing practices between the two varieties of Swedish warrants serious further investigation involving sociolinguistic, social psychological, and ethnographic research.

Conclusion

This study makes a new contribution to research on assessments as sequence-closing thirds in the specific context of service encounters by offering an integrated analysis of sequential progression and vocal and embodied cues in producing assessments, further combined with an account of distributional aspects across participant roles and two varieties of the same language. The analysis demonstrates that task-completing assessments are an intrinsic feature of institutional interaction in which the participants go through a series of requests and fulfillment of them. The positive evaluations mark a successful outcome and closure of the previous, local paired actions, a longer section of two or more requesting sequences, or a whole series of service events at the conclusion of an encounter in pre-closing activities. Through their robust patterning as third-turn practices, these ratifications of task completion contribute to an ordered progression of incrementally arising service events and facilitate a transition to the next institutional task. In this sense, task-completing assessments contribute to intersubjectivity by providing a sequential basis for the participants’ shared understanding of the direction of the interaction, i.e., by accepting and ratifying a task completion and thereby suggesting a move to the next relevant task. They are not the only, albeit a central, device for this interactional function, and thus their deployment is optional rather than an absolute norm.

Task-completing assessments have a positive valence that is in accordance with the general positive outcome of the institutional transactions that are subject to evaluation. The use of assessments varies in frequency and their intensity between low- and high-grade items, a variation that is linked to certain factors. Firstly, a low-grade assessment may occur in a first task-completing sequence in a series of related requests that deal with some coherent section of interaction (for example, details of a show before the transition to payment-related issues). A high-grade item then can be produced at the completion of a later request–compliance sequence that develops the same project and marks the closure of a coherent section at the same time. This tendency displays a general orientation to upgrading in the subsequent position, somewhat similar to second assessments. Secondly, there is a difference in the assessment behavior associated with the institutional roles: The salespersons assess the outcome of service events to a lesser degree than the customers. This has to do with the different rights and obligations of the salespersons and customers that affect what kinds of actions they are expected to perform in a service encounter and how likely it is that these actions warrant an explicit appreciation. However, the data do not indicate that customers and salespersons assess in qualitatively different ways (cf. Lindström & Heinemann, Citation2009): low- and high-grade assessments are used by both groups. The dynamic shifts between customers and salespersons as assessors are also indicative of the participants’ agency, showing who is entitled to perform the evaluation and accept a task delivery as completed in a given sequence, i.e., displaying who has control of the sequence, which concurs with the findings in Antaki et al. (Citation2000).

We also observed some regular differences in intensity in the assessments between the data from Sweden and Finland. Both Swedish varieties contain moderate as well as intensive TCAs, but the moderate ones dominate in the Finland-Swedish encounters, whereas the Sweden-Swedish encounters have clearly more of the high-grade expressions, some of which are not used at all in the data from Finland. These differences are not lexical, in the sense that the assessment tokens are unknown for the speakers of one variety, but pragmatic, reflecting features of different normative orientations to an appropriate assessment metric in their sociocultural settings. The border marking, rather than an enthusiastically literal function, of these assessments is in both varities signaled with downgraded prosodic and embodied cues: low volume, fast tempo, corporeal orientation away from the other.

To conclude, task-completing assessments follow a regular pattern in service encounters. They are multifaceted actions in the sense that they both segment courses of local sequences or indicate termination of the whole encounter and convey an appreciating stance to the outcome of completed tasks. There are sequential, prosodic, and embodied features of their delivery that point to their primary pragmatic function, which is to mark interactionally arising unit boundaries and to coordinate the participants’ transitions from one task to the next.

Notes

1 For a more comprehensive overview of research on assessments within CA, see the introduction by Lindström and Mondada (Citation2009) to a ROLSI special issue on assessments.

2 See also, e.g., Heritage and Raymond (Citation2005) on the relationship between the sequential position of assessments and displays of epistemic authority in everyday interactions.

3 The research program is funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond 2013–2020, Grant ID M12-0137.

4 In this orientation to section closure, rather than to a single adjacency-pair sequence closure, we see some parallels to the use of high-grade assessments at the completion of longer interactional trajectories (like completing a questionnaire) observed by Antaki et al. (Citation2000) in client-therapist interactions.

5 See Persson (Citation2015) for other-repetitions with a registering function.

6 This use of turn-initial å (och) can be related to Heritage and Sorjonen’s (Citation1994) observation of and-prefaced questions in which the additive conjunction links the question to preceding questions and marks it as agenda based.

7 See also Antaki et al. (Citation2000) on high-grade assessments in completions of the interaction as a whole.

8 Our service encounter corpus will be made available for scientific use via the Language Bank of Sweden after the completion of the research program (end of 2020). In the meantime, raw data are open to enquiries.

9 This also resonates with Sacks’s (Citation1995, p. 226) definition of a culture as “an apparatus for generating recognizable actions.”

References

- Antaki, C. (2002). ‘Lovely’: Turn-initial high-grade assessments in telephone closings. Discourse Studies, 4(1), 5–24. doi:10.1177/14614456020040010101

- Antaki, C., Houtkoop-Steenstra, H., & Rapley, M. (2000). ‘Brilliant. Next question…’: High-grade assessment sequences in the completion of interactional units. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 33(3), 235–262. doi:10.1207/S15327973RLSI3303_1

- Beeching, K., Ghezzi, C., & Molinelli, P. (Eds.). (2018). Positioning the self and others: Linguistic perspectives (pp. 19–49). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Berry, J. W. (2015). Acculturation. In J. E. Grusec & P. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 520–538). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Drew, P., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (Eds.). (2018). Requesting in social interaction. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Felix-Brasdefer, J. C. (Ed.). (2015). The language of service encounters. Cambridge, England: CUP.

- Fox, B. (2015). On the notion of pre-request. Discourse Studies, 17(1), 41–63. doi:10.1177/1461445614557762

- Goodwin, C. (1984). Story structure and organization of participation. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 225–247). Cambridge, England: CUP.

- Goodwin, C. (1986). Between and within: Alternative and sequential treatments of continuers and assessments. Human Studies, 9(2–3), 205–218. doi:10.1007/BF00148127

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (1987). Concurrent operations on talk: Notes on the interactive organization of assessments. Pragmatics, 1(1), 1–54.

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (1992a). Assessments and the construction of context. In A. Duranti & C. Goodwin (Eds.), Rethinking context: Language as an interactive phenomenon (pp. 147–189). Cambridge, England: CUP.

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (1992b). Context, activity, and participation. In P. Auer & A. DiLuzio (Eds.), The contextualization of language (pp. 77–99). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Grahn, I.-L. (2017). Initierade tackhandlingar i sverigesvenska och finlandssvenska vårdsamtal – Sekvensorganisering och funktion [Initiating thanking actions in Sweden-Swedish and Finland-Swedish health-care conversations – Sequence organization and function]. Språk och interaktion, 4(4), 89–110.

- Halonen, M., & Koivisto, A. (in press). Moving money: Money as an interactional resource in kiosk encounters in Finland. In B. Fox, L. Mondada, & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Encounters at the counter: Language, embodiment and material objects in shops. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Henricson, S., & Nelson, M. (2017). Giving and receiving advice in higher education. Comparing Sweden-Swedish and Finland-Swedish supervision meetings. Journal of Pragmatics, 109, 105–120. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.12.013

- Heritage, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). The terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in talk-in-interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1), 15–38. doi:10.1177/019027250506800103

- Heritage, J., & Sorjonen, M.-L. (1994). Constituting and maintaining activities across sequences: And-prefacing as a feature of question design. Language in Society, 23, 1–29. doi:10.1017/S0047404500017656

- Hoey, E. M. (2017). Sequence recompletion: A practice for managing lapses in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 109, 47–63. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.12.008

- Keevallik, L. (2010). Pro-adverbs of manner as markers of activity transition. Studies in Language, 34(2), 350–381. doi:10.1075/sl.34.2

- LeBaron, C., & Jones, S. E. (2002). Closing up closings: Showing the relevance of the social and material surround to the completion of interaction. Journal of Communication, 52(3), 542–565. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02561.x

- Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge, England: CUP.

- Levinson, S. C. (2013). Action formation and ascription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), Handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 103–130). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lindström, A. (2005). Language as social action: A study of how senior citizens request assistance with practical tasks in the Swedish home help service. In A. Hakulinen & M. Selting (Eds.), Syntax and lexis in conversation: Studies on the use of linguistic resources in tal-in-interaction (pp. 209–230). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Lindström, A., & Heinemann, T. (2009). Good enough: Low-grade assessments in caregiving situations. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 42(4), 309–328. doi:10.1080/08351810903296465

- Lindström, A., & Mondada, L. (2009). Assessments in social interaction. Introduction to the special issue. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 42(4), 299–308. doi:10.1080/08351810903296457

- Macbeth, D. (2003). Hugh Mehan’s “Learning Lessons” reconsidered: On the differences between the naturalistic and critical analysis of classroom discourse. American Educational Research Journal, 40(1), 239–280. doi:10.3102/00028312040001239

- Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mondada, L. (2009). The embodied and negotiated production of assessments in instructed actions. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 42(4), 329–361. doi:10.1080/08351810903296473

- Mondada, L. (2014). Pointing, talk, and the bodies. Reference and joint attention as embodied interactional achivements. In M. Seyfeddinipur & M. Gullberg (Eds.), From gesture in conversation to visible action as utterance (pp. 95–124). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Myers, G. (2000). Entitlement and sincerity in broadcast interviews about Princess Diana. Media, Culture & Society, 22(2), 167–185. doi:10.1177/016344300022002003

- Nilsson, J., Norrthon, S., Lindström, J., & Wide, C. (2018). Greetings as social action in Finland-Swedish and Sweden-Swedish service encounters – A pluricentric perspective. Intercultural Pragmatics, 15(1), 57–88. doi:10.1515/ip-2017-0030

- Norrby, C., Wide, C., Nilsson, J., & Lindström, J. (2015). Interpersonal relationships in medical consultations. Comparing Sweden Swedish and Finland Swedish address practices. Journal of Pragmatics, 84, 121–138. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2015.05.006

- Norrby, C., Wide, C., Nilsson, J., & Lindström, J. (2018). Positioning through address practice in Finland-Swedish and Sweden-Swedish service encounters. In K. Beeching, C. Ghezzi, & P. Molinelli (Eds.), Positioning the self and others: Linguistic perspectives (pp. 19–49). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Ogden, R. (2006). Phonetics and social action in agreements and disagreements. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 1752–1775. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2005.04.011

- Persson, R. (2015). Registering and repair-initiating repeats in French talk-in-interaction. Discourse Studies, 17(5), 583–608. doi:10.1177/1461445615590721

- Pomerantz, A. (1978). Compliment responses: Notes on the co-operation of multiple constraints. In J. Schenkein (Ed.), Studies in the organization of conversational interaction (pp. 57–101). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge, England: CUP.

- Rhys, C. (2016). Grammar and epistemic positioning: When assessment rules. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(3), 183–200. doi:10.1080/08351813.2016.1196546

- Rossi, G. (2015). Responding to pre-requests: The organization of hai x ‘do you have x’ sequences in Italian. Journal of Pragmatics, 82, 5–22. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2015.03.008

- Saari, M. (1995). Synpunkter på svenskt språkbruk i Sverige och Finland [Notes on the Swedish usage in Sweden and Finland]. Folkmålsstudier, 36, 75–108.

- Sacks, H. (1995). Lectures on conversation ( Gail Jefferson, Ed.). Oxford, England: Blackwell.

- Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction. A primer in conversation analysis (Vol. 1). Cambridge, England: CUP.

- Schuetz, A. (1953). Commonsense and scientific interpretation of human action. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 14(1), 1–38. doi:10.2307/2104013

- Sorjonen, M. L., & Raevaara, L. (2014). On the grammatical form of requests at the conveninece store: Requesting as embodied action. In P. Drew & E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.), Requesting in social interaction (pp. 243–268). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Streeck, J. (2014). Mutual gaze and recognition. Revisiting Kendon’s “Gaze direction in two-person conversations”. In M. Seyfeddinipur & M. Gullberg (Eds.), From gesture in conversation to visible action as utterance (pp. 35–56). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Thompson, S. A., Fox, B. A., & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2015). Grammar in everyday talk. Building responsive actions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix

In , the number of assessments presented in is related to the number of individual speakers who produced assessments in the data sets from Sweden and Finland respectively.

Table A1. Number of speakers that produced low-grade and high-grade assessments in the data sets from Sweden and Finland.