ABSTRACT

This article investigates a recognizable embodied practice for displaying dissent: the “eye roll,” whereby the eyes are rolled up or sideways in their sockets as a response to something said or done. On a corpus of videoed interaction, it shows that: (a) the eye roll may be only the most salient—visible—element of a constellation of practices embodying dissent; and (b) it can be quite specific in its selection of recipients and can be used to pursue affiliation with another party. Investigation suggests that the eye roll is in fact a protest in response to someone going too far. As an expression of stance that may not be visible to the party whose action it targets, the eye roll is collusive for those who witness it: In its ambivalent status lies its value as an interactional object. Data are in British and American English.

At the G20 summit in Hamburg in 2017, what attracted the most news coverage was not the official business but something that happened in an interval between meetings and lasted less than half a second: German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s eye roll in response to something said by Russian President Vladimir Putin ().Footnote1

Figure 1. Angela Merkel produces an eye roll in response to Vladimir Putin, G20 Summit, July 7, 2017

There is no indication that Putin registers it—he is not looking at Merkel as she produces it—so the fact that it was spotted and brought to the attention of the world’s media gave its production a collusive quality, apparent to all but the person to whom it was a response. Such indeed was the tenor of the news coverage that followed, which took the eye roll to be a glimpsed expression of Merkel’s “real,” clearly negative, feelings:Footnote2 that is, feelings she did not reveal during the formal business of the day and that were decidedly at odds with any officially expressed stance. In the fraction of a second it took to produce, the eye roll afforded us a privileged insight into the distinction between what is designed for its recipient and what is not, and so what is authentic—or so the news coverage implied.

In what follows, we examine these characteristics using multimodal conversation analysis (CA) (Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation2000; Mondada, Citation2016) to investigate the eye roll as a recognizable and culturally salient embodied interactional practice. The concern in this article will be to investigate what kind of action this is: What does something so fleeting serve to do, and what are its interactional consequences? The current study, in common with prior studies of the eye roll, examines its use in the context of British and American English interaction.

Background

As an interactional resource, the eye roll conforms most closely to that set of practices Kendon calls “facial gestures such as eyebrow movements or positionings, movements of the mouth, head postures and sustainments and changes in gaze direction” (Kendon, Citation2004, p. 310; italics added), a term adopted in work by Bavelas et al. (Citation2014) and Bavelas and Chovil (Citation2018), who investigate the pragmatic functions that such facial gestures serve. However, research on the eye roll itself is sparse, and sequential studies of its use across contexts nonexistent. What there is has emerged from the perspectives of social psychology and anthropology, which associates it exclusively with one demographic: girls. One prominent claim is that it is used predominantly by adolescent girls as a form of passive-aggressive behavior as a response to displeasure (Karlbaugh & Haviland, Citation1994; Shute et al., Citation2002). In an interactional study of the aggressive interactions of preadolescent girls, M. H. Goodwin and Samy Alim (Citation2010) show how the eye roll is used alongside the teeth suck and neck roll in racial stereotyping in insult sequences—a practice they call “transmodal stylization.” Notwithstanding the claim that “adolescent girls have practically monopolized the ocular gesture as a form of communication” (Damour, Citation2016), the following will show the eye roll deployed by a range of interactants, none of whom, as it happens, are adolescent girls; furthermore, it seeks, for the first time, to investigate the use of the eye roll as a generic resource in its home base of interaction. Here we investigate an initial instance before examining a number of such cases to establish the generic characteristics of the eye roll in the light of its placement in sequences of talk. The cases shown here, selected for their clarity, are taken from a larger corpus of 30 instances, some in so-called mundane conversation, some in institutional talk. In view of the fact that most of the exemplars presented here are available in the public domain (e.g., on YouTube),Footnote3 and so by definition mainly in institutional contexts and already characterized by their uploaders—and so searchable—as instances of eye rolls, the intention here is not to make distributional claims but sequential observations. The clips are available at the publisher’s website.

An initial case

The following exchange, filmed in the United States in the early 1970s, is one discussed and analyzed in detail in Schegloff (Citation2005, p. 460), although without particular analytic attention to the eye roll; here it has been retranscribed in accordance with multimodal conventions.Footnote4 In it, 14-year-old Virginia, sitting at the dinner table, pleads with her mother to get a dress that she has evidently craved for some time.

1. Virginia, 1:34 (V = Virginia (14-year old daughter) (+), M = Mom (*), P = Prudence (girlfriend/fiancée of Wesley, Virginia’s brother)

As Schegloff (Citation2005) notes, Mom’s response to Virginia’s plea resists the proffered recognition embodied in the form “that dress” (line 1) by initiating repair on the reference (line 3). But just as Virginia launches a further—as it happens, uninformative—response, Mum, in overlap, registers both recognition of the referent with “Oh Virginia” as well as its inaptness (Heritage, Citation1984, Citation1998), going on to make explicit what was implicit from line 1: “we’ve been through this befawh” (lines 5–6), which, while not directly refusing the plea, conveys through the complaint that “requests along this line have been taken up and denied (with the implication that it is being denied again” (Schegloff, Citation2005, p. 461).

Mom’s initial verbal response, “Oh Virginia,” is adumbrated by a number of embodied actions. In the first instance, Virginia had launched her plea as she was taking some bread from a basket held in both hands by Mom. As she says “Drehss?,” Mum furrows her brow, gazing at Virginia in a momentary “hold” of the body (Floyd et al., Citation2016; Sikveland & Ogden, Citation2012). She then releases the bread basket with her right hand, disengaging her gaze and throwing her head back as she produces the eye roll, saying “Oh Virginia” (see ). Schegloff proposes here that “the ‘Virginia’ with eye roll displays exasperation, most likely with the recurrence of this inaptness” (Schegloff, Citation2005, p. 461). However, note that Schegloff’s characterization pertains to the one instance only, asserted in the course of a general analysis of the wider sequence rather than an analysis of the singular practice per se. Moreover, in this instance, the eye roll is produced as one of a constellation of sudden, vehement movements by Mom produced in conjunction with her disobliging exclamatory response; as Schegloff’s analytic gloss suggests, “exasperation” is not displayed solely by the eye roll but in its conjunction with the verbal (“Virginia”).

In this particular instance, Mum’s eye roll and the simultaneous embodied actions are collectively designed to be visibly and audibly responsive to, and triggered by, Virginia’s imploring. In its placement in the course of Virginia’s identification of the dress, done at the first opportunity, the eye roll is brought off as a visceral eruption, immediately responsive to the precipitating turn. In this respect, the eye roll resembles that category of practices Goffman calls “response cries”—although of course not “cries” as such—of which he says: “We see such ‘expression’ as a natural overflowing, a flooding up of previously contained feeling, a bursting of normal restraints, a case of being caught off-guard” (Goffman, Citation1978, p. 800). Indeed, the placement of Mum’s response to Virginia, produced in interjacent overlap (Jefferson, Citation1986), invests the eye roll with this kind of expressive, reactive quality as characterized by Goffman. However, for all that the eye roll is brought off as a straightforwardly expressive reaction, multimodal research such as that of M. H. Goodwin (Citation1980) on processes of mutual monitoring, Goodwin and Goodwin (Citation1987, Citation2004) on concurrent operations on talk, and Mondada (Citation2011, Citation2016) on parallel courses of multimodal action shows us that such displays of stance are profoundly interactional and organized with respect to the emerging turns-at-talk. Furthermore, work by Kaukomaa et al. (Citation2015) shows how the recipient’s facial expressions shape the ongoing talk of the current speaker. A central aim of the current study is therefore to examine the interactional organization and implementation of this particular embodiment. In this respect, the study builds on Ryle’s famous distinction between a blink and a wink (Ryle, Citation1971), the former being involuntary, the latter a designed communicative signal. To examine the eye roll as a generic practice, it will be necessary to examine a number of such cases across a diversity of contexts.

The eye roll in interaction

Extract 2 shows an example of an eye roll that contrasts on a number of dimensions with that produced by Mum in Extract 1—most obviously in its minimal character, but also in its lack of verbal elaboration, and also in that a participant does not produce an eyeroll to be visible to the producer of the turn to which it is a response. June and Leon Bernicoff are a married couple filmed for the TV program Gogglebox, which captures families’ responses as they watch British television. In the following exchange, celebrity cook Nigella Lawson has just appeared on television as June and Leon watch (see also Ogden, Citation2020).

(2) “Gogglebox”, Channel 4, November 5th, 2013. L = Leon (+); J = June (*)

As Lawson appears on television, Leon produces an assessment (line 1) and, after a micropause, another—this time vivid and idiomatic—assessment that, following the first, is hearable as an account for it: “well busted” (buxom). June has, from lines 1–4, maintained the same posture, gazing at the screen, with her left hand cradling her chin, with the middle finger up against her cheek; after Leon produces his lewd assessment, June, maintaining the same posture, does a simultaneous dental click (on which, see Ogden, Citation2020) and eye roll, followed by a headshake ().

Thus the eye roll is, as in Extract 1, not the only indication of dissent; it is heralded here by the dental click, a familiar practice conventionalized as “tutting” in disapproval (Ogden, Citation2013, Citation2020; Reber, Citation2012; Wright, Citation2011) and accompanied by the headshake. But while the eye roll is buttressed by other indications of dissent, June does not turn her head to seek Leon’s gaze; nor does she verbalize any dissent as she produces the eye roll. In this respect, unlike Mom’s eye roll to Virginia, June’s response is designed not to be visible to its recipient. It thus stands in contrast to that in Extract 1 in that it is not produced in view of the party to whom it is a response. This is not, of course, to suggest that the entire display of dissent is muted; the click is, after all, audible and so available to be heard, even though Leon does not visibly register it.

The following extract also shows an eye roll that is minimal in character but that, in contrast, is produced by someone facing the party to whom it is a response. This case, unlike those in Extracts 1 and 2,Footnote5 is that of a clearly institutional interaction: a broadcast interview. Institutional interaction is standardly characterized by sustained displays of what Parsons (Citation1951) calls “affective neutrality” on the part of the professional; the newsworthiness of Angela Merkel’s eye roll is precisely down to the deviation from affective neutrality that it represented in the context of high-level diplomacy. With respect to political interviews, as Clayman (Citation1992) shows, affective neutrality requires a display of political neutrality on the part of the interviewer. However, in the following, CNN’s Anderson Cooper, interviewing President Trump’s counselor KellyAnne Conway about the President’s firing of FBI director James Comey, produces an eye roll that, like Merkel’s—produced against the backdrop of an institutional encounter—would seem to embody precisely Goffman’s characterization of a response cry as “a bursting of normal restraints, a case of being caught off-guard” (Goffman, Citation1978, p. 800).

(3) Interview on “Anderson Cooper 360”, 10th May 2017. AC = Anderson Cooper, interviewer (*); KC = KellyAnne Conway, counselor to the President (+)

Cooper puts before Conway a basic contradiction in the White House position (lines 1–4). In response, Conway does not address this but instead accuses him by attacking the question (line 6) and then shifting the topic to shoehorn in an extensive boast (“I was on your show often las” Fall sayin’ we were gonna win Michigan and how we were goin’ t’ do it’) that has nothing to do with the question just asked. As Conway moves to an assessment (line 10, “So that was fun”), Cooper does an eye roll, with a slight shake of the head as he does so ().

By the norms of interviewing, the eye roll is produced in what is properly the other speaker’s turn and visibly responsive to Conway’s “told you so” reference that is hearably evasive of Cooper’s question. However, although the sense, as with Mum’s in Extract 1, that an eye roll is expressive and visceral may come from its position in the course of another’s extended turn, aspects of its composition suggest otherwise. Although, as in Extracts 1 and 2, the eye roll is accompanied by another embodiment—in this case a slight shake of the head—this is as minimal and fleeting a response as Mum’s is maximal and expressive in its amplitude. An eye roll leaving the face otherwise impassive—as is also the case in Extract 2, visible from —is not necessarily designed to be visible to the person to whose turn it is responding; indeed, there is no evidence in the talk that Conway registers it. She is gazing down (possibly at her notes) as he does the eye roll, lifting her gaze back up after it (see ).

So although there are clear elements of viscerality in this eye roll, it is clearly an object designed for its institutional context and in that respect is interactionally shaped. However, both this example of Cooper’s—and indeed, of Angela Merkel’s () and June’s ()—are distinct from that in Extract 1 in that the eye roll is not designed for the party to whom it is a response. As a broadcast interviewer, however, Cooper is clearly visible, and so his response is available to his audience. In that respect, just as with Merkel’s and with June’s in , the eye roll is a collusive interactional object.

The following case also takes place in the context of an interview, but unlike the previous case, the eye roll is produced in full visibility of the party to whom it is a response. The context is that the British Conservative Prime Minister, Theresa May, has just had her proposed Brexit deal rejected by a vote in the House of Commons; in the wake of this, the journalist Emily Maitlis is interviewing politicians from the Labour and Conservative parties. In the following exchange, she questions the Labour politician, Barry Gardiner, about what the Labour party’s manifesto position would be on Brexit, should a General Election be called.

(4) Newsnight, BBC2, 13th March 2019. EM = Emily Maitlis, interviewer (*); BG = Barry Gardiner, Labour MP (+). Sitting between Maitlis and Gardiner is Conservative MP Nadhim Zahawi (⊥). EM has sheaf of papers in her RH, and her LH is raised, holding a pen:

As in Extract 3, an interviewer asks a question (here at lines 3–4: “what Brexit vision will be on your manifesto then”), in response to which the interviewee launches a turn that is hearably evasive of the question: “to negotiate the deal that we have set out” does not outline the “Brexit vision” sought in the question. When the interviewer, Maitlis, at the first possible TRP, proposes this to be a manifesto commitment, thus pursuing her original question (“that’s gonna be on the leaflet”, line 6), the interviewee, Gardiner, abandons the continuation of his original responsive turn, not to agree or disagree with the proposal, but instead to suggest that the manifesto is still to be decided (“we will decide what our manifesto position is … ”)—thus continuing to resist the question (see ).

At the first TRP (line 10) at the word “is,” Maitlis displays the first signs of dissent by sitting back, sighing, and breaking gaze with Gardiner, picking up her sheaf of papers and bringing them down on their edge on the desk; as she brings the papers down, she produces an eye roll as she looks to her right, as Gardiner comes to the end of his second TCU (“as we normally do”) (see ).

So, as in the previous case, an interviewer produces an eye roll as part of an embodied response to a hearably evasive answer from an interviewee—an eye roll that is similarly adumbrated by other embodied conduct indicating dissent. However, in this instance, the embodied conduct by Maitlis, with the postural shift, the rearrangement of the papers, and the movement of the head away from the interviewee, is as expansive as Cooper’s had been minimal. This instance also differs from the previous example in two other important respects. The first is in the configuration of the eye roll itself; whereas Cooper’s in is clearly a roll of the eyeballs upwards toward the eyebrows, the one produced by Maitlis, while clearly an eye roll, is more evidently to the side rather than directly upwards. This suggests that the central characteristic of the eye roll is the fleeting movement of the eyeballs—upwards or to the side—rather than their direction as such.Footnote6

The last way in which this instance differs from that involving Cooper is that the eye roll is produced in full view of a recipient who is gazing at the producer (as is evident from ). There is no conclusive evidence of orientation to the eye roll in the content of Gardiner’s turn; however, the hitch in his talk in its wake (the self-repair in “it’s a- it’s a democratic party,” lines 11–12) might indicate a responsiveness to it. Maitlis’s conduct in the wake of her eye roll continues the visible display of dissent, as she circles something on her notes and scribbles vigorously on them, as she shakes her head. After a verbal repudiation, in a hearably smiling voice, of Gardiner’s assertion at lines 12–13 with a highly agentive repetition of his words “It’s not made up at a::ll” (lines 15–16), opening her hands out into a “palm up” gesture (Clift, Citation2020), Maitlis goes on to clarify, with an “I mean” preface (Maynard, Citation2013) with a vivid idiomatic display of exasperation: “people are literally pulling their hair out tonight” (lines 17–19), thus verbally underscoring a stance already indicated by the eye roll. This exchange thus makes particularly clear what is evident across all the cases so far: that the eye roll is by no means the initial or the only indication of disagreement or resistance from a participant, forming part of a constellation of embodiments that collectively display dissent.

Although Maitlis is in full view of Gardiner as she produces the eye roll, as noted earlier, Gardiner does not explicitly respond to it in his talk. In contrast, the following case shows that an eye roll may motivate a verbal response. The context is a panel entitled “Running for the People” at the Netroots Convention for progressive political activists. Among the panel is Congressman Keith Ellison. From the floor, an activist, Felicia Teter, identifying herself as a member of the Yakama Nation in Washington State, addresses the panel.

(5) Netroots Nation Annual Conference, Atlanta, 2017. FT = Felicia Teter; ARR = panel chair Anthony Rogers-Wright; AUD = audience (applause marked in lls. 15 & 17 by x).

At lines 10–11, Teter produces a negative assessment of a common claim made about the United States, that “we are a country of immigrants,” initially attributing it only to generalized “people” (line 10) but then, as she flatly asserts the contrary, continuing with a direct attribution of that assertion to Keith Ellison (lines 14–16). As she proceeds to continue her turn (line 16) in what is hearably about to be a negative assessment, she cuts off to launch a directive that, for all that it is “please”-prefaced, brusquely admonishes Ellison for his response—the coldly impersonal turn-final form of address (“sir”) only underwriting the delivery of the censure. “Please don’t roll your eyes, sir” is clearly responsive to what Teter sees as she looks at Ellison, having directly attributed to him the claim she has just deprecated. Such a case shows the extent to which, fleeting though it might be, as long as the eye roll is not designed to be occluded from the party to whom it is a response,Footnote7 it is vulnerable to being registered and called out—here becoming itself the priority matter for Teter, and the focal business of the interaction, so redirecting the course of the talk. In this respect, it recalls the observations made in Kaukomaa et al. (Citation2015) on how facial expressions can redirect talk, although in that particular case participants are working toward achieving a shared stance, where here there is clear disaffiliation. What this case shows is that the eye roll is always potentially visible as a communicative, interactional object—if not necessarily to the party to whom it responds.

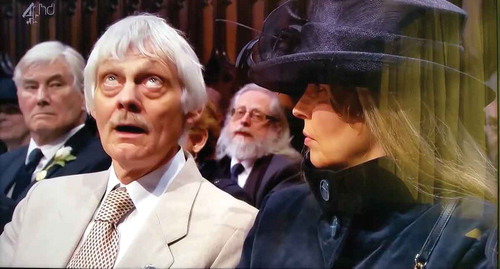

A final case here underlines this point conclusively. It is both highly visible and, unlike the other cases here, selects a specific party as its recipient. The occasion is the reburial of King Richard III of England in Leicester Cathedral in 2015. Since his death in 1485, the whereabouts of King Richard had been the subject of much speculation; at the forefront of efforts to locate the remains was the “Looking for Richard” project, founded by Philippa Langley of the Richard III Society. A historian, John Ashdown-Hill, first proposed to Langley, in 2005, that the King’s remains would be found under the site of a municipal car park in Leicester; Langley suggested that he contact the University of Leicester’s archeology department to propose that they undertake excavations there. He duly did so, in 2009, but received no response. It was only three years later that the university was persuaded to take on the project, and the bones of King Richard were found, where Ashdown-Hill had proposed, on the first day of the dig in 2012. In the following extract, the eulogy is being delivered by Professor Gordon Campbell of the University of Leicester during the reburial service. John Ashdown-Hill is sitting with Philippa Langley to his left in the congregation. Campbell’s eulogy has so far made no mention of Ashdown-Hill, saying only that “The recovery and identification of the bones of King Richard was the work of the University of Leicester’s archeology team… .” As he continues with “Beyond the University …, ” Ashdown-Hill can be seen shaking his head vigorously in dissent.

(6) (GC = Professor Gordon Campbell, eulogist, University of Leicester; AH = John Ashdown-Hill, historian (*); PL = Philippa Langley, Richard III Society & “Looking for Richard” project) (+):

In Extracts 2 and 4, headshakes are produced after the eye roll in a multimodal display of dissent. In Extract 3, the headshake is produced simultaneously with the eye roll indicating Cooper’s initial dissent from Conway’s response. In Extract 6, the headshake adumbrates the eye roll but on an altogether more amplified scale. Although both are produced in an institutional context, Ashdown-Hill’s extended shaking of the head as Campbell gives credit to the University, making no mention of Ashdown-Hill’s decisive role, is as maximal in its amplitude as Cooper’s headshake in Extract 3 is minimal. In this particular context—that of the display of common respect and assent that standardly characterizes the eulogy—such a vigorous display of disaffiliation is all the more visible.

The eye roll here is clearly not designed for the person to whose turn it is a response. Allied to what M. H. Goodwin (Citation1997) has called “byplay,” or commentary on ongoing talk,Footnote8 it is clearly visible to a specific other—and indeed potentially the broadcast audience—and in that respect constitutes a highly collusive stance marker. As Ashdown-Hill turns to Langley, she turns to him and, mutual gaze having been secured alongside a very visible sigh—his open mouth contributing to the visibility of the sigh—the eye roll he produces is of theatrical magnitude (see ).

Indeed, the collusion that the eye roll pursues is ratified by the recipient’s conduct in turn; she produces a sigh in response to his as they break mutual gaze.

The vigorous headshakes and the head turn that herald the eye roll, alongside the expansive sigh, render it as far from Goffman’s visceral eruption, or “natural overflowing,” as it is possible to imagine and underscore the extent to which it is a profoundly interactional object. It is the business of the moment, not produced en passant like the previous case, and not an adjunct to any other action, such as Mum’s in Extract 1. Like all the previous cases, it disaffiliates from what has just been done, in this case praising the university. However, unlike the previous cases, in which an eye roll is produced in response to something said, this disaffiliation indicates a sin of omission—a failure to recognize Ashdown-Hill’s own contribution—as much as a sin of commission—bestowing eulogistic praise on the wrong recipient.

Discussion: Going too far

We have now examined a number of cases that underscore the fact that, despite its reactive, visceral, and expressive characteristics, the eye roll is wholly interactionally shaped. The final example, in Extract 6, is the one in which its interactional potential is most fully mobilized—the closest in the collection here to the collusive “wink” discussed by Ryle.Footnote9 All eye rolls are part of a constellation of embodiments indicating dissent from something just said or done, available to be registered by whoever may be gazing at the producer; but in this particular case, in addition, the eye roll is used simultaneously to indicate dissent while pursuing affiliation by picking out a specific recipient.

All our examples show that even those not publicly registered by the parties to whom the eye roll is a response are registered by others: perhaps not even contemporaneously but certainly, thanks to the capture of these instances on film, subsequently. And minimal though it may be, its salience is such that it is reportable—and indeed, often used as a shorthand as the initial response to an action thereby cast as objectionable in some way. In the following radio news report during the fraught negotiations between the UK and the EU over Brexit, the BBC’s Europe editor, Katya Adler, reporting on a European summit, is asked by a fellow journalist whether there was any discussion of Brexit; she responds as follows:

(BBC Radio 4 Today program, May 29, 2019)

Of course, reports of eye rolls are not data, but they do illuminate what actions the participants understand eye rolls to be implementing. The “massive eye-roll” Adler reports, alongside the subsequent multiple no’s (Stivers, Citation2004) clearly embody the objection Bettel displays in response to her persistence—the assessment item “massive” serving to imply the scale of that objection.

The fact that the eye roll is reported is testament to its visibility and so its interactional salience. We cannot know whether what Adler reports was accompanied by other signs of dissent (such as the click, headshake, and sighing that we see in Extract 2, for example), just as the photo of Merkel in misses any possible accompanying indications of resistance or disagreement; the eye roll in each case serves as a concise representation of dissent. Although these two instances—one reported, one photographed—capture the eye roll as the most salient indicator of dissent, our examples showing the eye roll in its sequential context reveal that it is heralded, accompanied, and/or followed by other multimodal signs of resistance.

How then to distinguish the eye roll from other dissenting responsive practices, such as a headshake or a click? As we saw earlier, Schegloff (Citation2005) proposes of one specific instance that the eye roll, in conjunction with other embodied and verbal practices, displays exasperation. But before we generalize this across the cases we have seen, we should examine the actions to which the eye roll is a response:

Ext Turns to which eye-roll is a response

From this it is evident that the eye roll is deployed in response to: an imploring plea (1); a lewd assessment (2); a digressionary, opportunistic, self-righteous boast (3); an evasive answer (4); an accusation (5); and misdirected praise (6). Exasperation implies frustration with a persistent line of action (Clift, Citation2014); although such a persistent line is apparent in some of the cases here, it does not apply to all, such as the assessment in (2). This, while not a display of persistence, is surely cast by its recipient in response as unseemly and inappropriate, given the context. And indeed, all of the aforementioned turns might be characterized as in some sense excessive, overstepping the mark, or going too far with a line of action: This is particularly salient in Virginia’s persistence in Extract 1, Leon’s assessment in Extract 2, Conway’s boast in Extract 3, and the reported eye roll of Xavier Bettel in response to Katya Adler’s assertion that she “tried to push” the European leaders on the subject of renegotiating Brexit. So although the eye roll may embody exasperation in response to persistence on some occasions, our examples reveal that that persistence is only one form of going too far—and so exasperation is but one possible stance it can embody. More globally, the responses to the aforementioned turns 1–6 collectively propose that the action the eye roll implements, as a response to going too far, is a protest at what has been said or done. As Extracts 2, 3, 4, and 6 attest, it is not designed in the first place to be a protest that disrupts the progressivity of the sequence (Schegloff, Citation2007) and the ongoing action (even though, as we see in Extract 5, it is vulnerable to being called out, which indeed disrupts progressivity); these exemplars show that, although accompanied or adumbrated by other signs of dissent, such as clicks and headshakes, the eye roll is produced in tandem with essentially compliant conduct, and, as in Extracts 2 and 3, may constitute an indication, however fleeting, of resistance.Footnote10

In a number of cases here—Extracts 3, 4, 5, and 6, as well as that produced by Merkel in —the eye roll is visibly produced in the course of another’s turn, which is what invests it with the visceral quality, the “bursting of normal restraints” (Goffman, Citation1978, p. 800) that Goffman attributes to response cries. The positioning of the eye roll, not just in the sequential context (where activities such as interviewing and attending eulogies may be standardly exempt from such displays of dissent) but in the context of the turn, is thus critical to this impression. In addition, there is the fact that, in all cases but Extract 6, the producer of the eye roll does not visibly seek out a recipient. The eye roll is thus brought off as a private moment in the course of another activity; in Goffman’s lovely phrase, an “invitation into our interiors” (p. 814). This “invitation” is what invests the eye roll with a collusiveness for those who see it.Footnote11 Indeed, in Extracts 1 and 4 (and Extract 5, which, even though not visually accessible, becomes evident in Teter’s callout), the producer of the eye roll is directly facing the party to whom it is a response, and that party is gazing at them while they produce it. In these cases it can at least be presumed that the producer of the eye roll orients to the public availability and witnessability of their embodied actions—and specifically to the possibility that the party to whom it is a response is witnessing it, so inviting collusion. The collusive quality of the eye roll thus accounts for the glee that greeted Merkel’s: a glimpse of authenticity shared with everyone but the party to whom it was a response.Footnote12

In contrast, Extracts 5 and 6 show instances of eye rolls that become the focal activity, albeit in distinctive ways. In Extract 5 the eye roll is visible to the party to whom it responds and, explicitly referenced, becomes the focal business of the exchange. In Extract 6, by contrast, the eye roll is produced by someone not necessarily visible to the party to whom it responds—at the very least, there is no evidence in the delivery of the eulogy that the eye roll is registered. But although in Extract 5 the suspension of the turn to draw attention to the eye roll treats it as a fugitive action caught on the sly, in Extract 6 the eye roll, as noted earlier, fully occupies the business between its producer and its recipient. Its capacity as a wholly interactional object is exploited here to the full.

Conclusion

The examination of the eye roll in its home base of interaction has established beyond doubt that it is a carefully designed practice that implements a protest at the just-prior action of another. In many cases it constitutes a fleeting protest that does not disrupt the progressivity of the sequence. In only one of the sequences we have examined (Extract 1) does the eye roll accompany a verbalized display of dissent. As we have seen, it is standardly but one practice—albeit the most salient—alongside another or others in a collective display of protest.Footnote13

What the data here have shown conclusively is that the eye roll as an interactional practice is not, as implied by previous literature, the idiosyncrasy of any one group, such as adolescent girls, but apparently a generic resource for interactants; the fact that almost half a century passed between the recordings of Extracts 1 and 2 also suggests a robustness of use across at least the generation since interactions have been routinely recorded. And although our extracts have focused on English interaction, it is clear from the reported eye rolls of Merkel and Bettel that it is familiar and recognizable more widely, at least in a European context.Footnote14 The available evidence for its use further afield is necessarily somewhat arbitrary.Footnote15 It is clear that more data on eye rolls across languages and cultures are required before this practice can be claimed to be universal.

There is also an important methodological upshot here. What this study has also underscored is the analytic equivalence of all parties to interaction. Recent multimodal research has noted the intrinsic bias toward speakers/doers as opposed to hearers/recipients; Mondada notes that “transcripts tend to be biased in favor of doers rather than recipients (for instance, the way an embodied action is looked at by the recipient is often transcribed and then ignored in the analyses)” (Mondada, Citation2016, p. 361), and the Goodwins, in a critical examination of Goffman’s concept of “footing,” note that participation in talk goes far beyond the categories of speaker and hearer. They remark that Goffman:

… privileges analytically what is occurring in the stream of speech … over other forms of embodied practice that might also be constitutive of participation in talk, and leads to a subtle but consequential focus on the speaker. (Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation2004, p. 225)

And indeed what eye rolls reveal is more complex than is captured in a simple dichotomy between a speaker/doer and hearer/recipient. As Extracts 2 and 3 show, an eye roll may be designed specifically not to become interactionally salient—and yet, may, as we see from Extract 5, become just that. So the eye roll might be said to have an ambivalent status—minimal enough to remain in the domain of the producer but visible enough to become interactionally salient. Critical in this respect is salience to whom: If salient to the party to whom it is a response, it is vulnerable to topicalization (as in Extract 5), if salient to others, then it remains an untopicalized—and thus collusive—interactional object between its producer and its recipients. In the ambivalence of the eye roll lies its interactional value. In its display of visible dissent that may or may not be seen by the party to whom it responds, the eye roll is one practice that reveals the nuances in the relationship between parties to interaction.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (14 MB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Notes

1 Available to see at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-40536916/angela-merkel-rolls-her-eyes-at-vladimir-putin

2 As embodied, for example, in the headline: “How the Merkel Eye-Roll Betrays Her Real Feelings on Her Allies,” The Telegraph, August 22, 2019.

3 I thank Emanuel A. Schegloff for permission to use Extract 1. Extracts 2–6 are in the public domain, filmed for broadcast (Extracts 2 and 6—Channel 4; Extract 3—CNN; 4—BBC2; and Extract 5—C-SPAN) and so collected with informed consent.

4 Transcription conventions follow the transcription system for embodied conduct developed by Lorenza Mondada, accessible at https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription. Embodied conduct for each speaker, following Mondada’s conventions, is indicated with a specific symbol, e.g., (*) or (+) on each transcript. I have tried to keep a balance between the readability of the transcript and analytic information for working purposes. What is visible on the tape is therefore not transcribed exhaustively. Some of the video clips start earlier than the transcription to provide some more sequential context, but I have endeavored to keep the excerpts as concise as possible.

5 Of course, being filmed for a television program, as is the exchange in Extract 2, produces anything but mundane conversation, but the participants, despite being filmed, are clearly not engaged in talk which is visibly and accountably institutional.

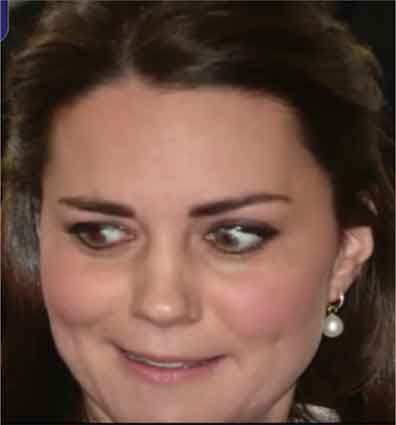

6 The following instance provides further evidence to support this position. The occasion is a charity event in New York, where the Duchess of Cambridge is helping to wrap some presents and talking to someone opposite her; as she does so, a supervisor behind her issues the abrupt and bald directive to “Keep wrapping.” In response, the Duchess turns first to look back over her left shoulder at the supervisor and then looks back with a slight smile at the person to whom she was earlier talking as she turns to look away briefly to her right as she produces an eye roll, continuing to wrap as she was earlier doing. The clip is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjqKvplay8s. It is evident that the eye roll produced by the Duchess is less upwards than sideways in its orientation, giving further support to the proposal that the eyes can be rolled upwards or sideways to be visible as an eye roll.

The clip is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjqKvplay8s. It is evident that the eye roll produced by the Duchess is less upwards than sideways in its orientation, giving further support to the proposal that the eyes can be rolled upwards or sideways to be visible as an eye roll.

7 As in the instance discussed in footnote 6, where the Duchess of Cambridge turns away from the prior speaker before she produces an eye roll.

8 Investigating byplay in talk in the context of conversational storytelling, M. H. Goodwin defines it as “a form of subordinated communication of a subset of ratified participants who make little effort to conceal the ways in which they are dealing with the speaker’s talk” (Goodwin, Citation1997, p. 78).

9 In discussing reference, Tomasello makes the same point with this story:

In an airplane, I take my seat on the aisle. There is a woman sitting next to the window in my row. A man comes into the row behind us, talking extremely loudly and obnoxiously. I look to the woman and roll my eyes, expressing an attitude best glossed as “Ugh, this is going to be a long trip.” I did not need to indicate the referent of my exasperation for her; it was clear to us both. (Tomasello, Citation2008, p. 80)

I am grateful to Marco Pino for drawing my attention to this excerpt.

10 That such resistance may be grounded in categorial concerns is particularly evident from Extract 2, where the assessment from Leon of the buxom quality of a cook is met with an eye roll from his wife.

11 As long as those who see it know what it is a response to. Haugh (Citation2008), discussing intentionality, examines a case where an eye roll, produced just as another is making an emotional tribute to the victims of a mass shooting, was widely taken by the television audience to show disrespect; the producer of the eye roll defended himself by claiming that he was responding to someone else.

12 The reporting of an eye roll can exploit this collusive quality. The following report that the former British Defense Secretary Gavin Williamson was the target of an eye roll from the Chief of Defense Staff Sir Nick Carter uses the eye roll to underscore the speaker’s own negative assessment of Williamson (the speaker here being “a senior military source”) and align with Carter, whose authentic response, it is implied, is revealed in the eye roll. Williamson had apparently suggested that the British Navy should arm the citizens of Gibraltar with paintball guns to splatter the Spanish Navy and Police vessels whenever they illegally entered British waters. A senior military source said:

Gavin Williamson comes up with some pretty off the wall things, but firing paintballs at the Spanish Navy beats the lot of them… . Nick Carter just rolled his eyes and said, “We’ll come up with some options Minister,” but everybody knew he wouldn’t. It’s properly potty. (The Sun, January 13, 2019)

Note here that Carter’s reported response—the eye roll accompanied by an apparently compliant verbal response—conforms with the majority of the cases here, where it does not disrupt the progressivity of the sequence.

13 This may ultimately be grounded in issues of processing; Holler and Levinson note “the convincing evidence for systematic associations between specific bodily signals (or combinations of several signals) and conversational social actions, representing the basis for efficient gestalt recognition” (Citation2019, p. 642) and further propose that “the temporally disaligned and distributed signals across different articulators and modalities may facilitate predictive language processing in face-to-face communication” (p. 643).

14 And indeed is conventionalized in various phrases, even if “rolling” as such is rendered differently, e.g., the Spanish ella puso los ojos en blanco (literally, “she put her eyes to white”) or the Italian Lei alzó gli occhi al cielo (“she lifted her eyes to the sky”) or Greek (γύρισε τα μάτια της (“she turned her eyes”).

15 So for example, Hong (Citation2019) in a discussion of the Korean concept of nunchi (the art of gauging others’ thoughts to build trust), suggests that “those who lack nunchi make peoples’ eyes roll,” so implying the familiarity of the practice in Korean culture. And in 2018, the eye roll produced by a Chinese journalist made global headlines when she was captured on film rolling her eyes as a fellow journalist asked a hearably sycophantic question to Communist party officials; her subsequent dismissal, and the censoring of the footage, is testament to the implicational significance of the eye roll. This is accessible at https://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2018/mar/14/chinese-reporters-dramatic-eye-roll-goes-viral-then-gets-censored-video

References

- Bavelas, J. B., & Chovil, N. (2018). Some pragmatic functions of conversational facial gestures. Gesture, 17(1), 98–127. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.00012.bav

- Bavelas, J. B., Gerwing, J., & Healing, S. (2014). Including facial gestures in gesture-speech ensembles. In M. Seyfeddinipur & M. Gulberg (Eds.), From gesture in conversation to visible action as utterance: Essays in honor of Adam Kendon (pp. 15–34). John Benjamins.

- Clayman, S. E. (1992). Footing in the achievement of neutrality: The case of news interview discourse. In P. Drew & J. Heritage (Eds.), Talk at work (pp. 163–198). Cambridge University Press.

- Clift, R. (2014). Visible deflation: Embodiment and emotion in interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(4), 380–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.958279

- Clift, R. (2020). Stability and visibility in embodiment: The ‘Palm Up’ in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 169, 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2020.09.005

- Damour, L. (2016, February 17) Why teenage girls roll their eyes. New York Times

- Floyd, S., Manrique, E., Rossi, G., & Torreira, F. (2016). the timing of visual bodily behavior in repair sequences: Evidence from three languages. Discourse Processes, 53(3), 175–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.992680

- Goffman, E. (1978). Response cries. Language, 54(4), 787–815. https://doi.org/10.2307/413235

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (1987). Concurrent operations on talk: Notes on the interactive organization of assessments. IPrA Papers in Pragmatics, 1(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1075/iprapip.1.1.01goo

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (2000). Emotion within situated activity. In A. Duranti (Ed.), Linguistic anthropology: A reader (pp. 239–257). Basil Blackwell.

- Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (2004). Participation. In A. Duranti (Ed.), A companion to linguistic anthropology (pp. 222–244). Basil Blackwell.

- Goodwin, M. H. (1980). Processes of mutual monitoring implicated in the production of description sequences. Sociological Inquiry, 50(3–4), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1980.tb00024.x

- Goodwin, M. H. (1997). Byplay: Negotiating evaluation in storytelling. In G. R. Guy, G. Feagin, D. Schiffrin, & J. Baugh (Eds.), Towards a social science of language: Papers in honor of William Labov, Volume 2: Social interaction and discourse structures (pp. 77–102). John Benjamins.

- Goodwin, M. H., & Samy Alim, H. (2010). “Whatever (Neck Roll, Eye Roll, Teeth Suck)”: The situated coproduction of social categories and identities through stancetaking and transmodal stylization. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 20(1), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1395.2010.01056.x

- Haugh, M. (2008). The place of intention in the interactional achievement of implicature. In I. Kecskes & J. Mey (Eds.), Intention, common ground and the egocentric speaker-hearer (pp. 45–86). Walter de Gruyter.

- Heritage, J. (1984). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 299–345). Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. (1998). Oh-prefaced responses to inquiry. Language in Society, 27(3), 291–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500019990

- Holler, J., & Levinson, S. C. (2019). Multimodal language processing in human communication. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(8), 639–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.05.006

- Hong, E. (2019). The power of nunchi. Penguin.

- Jefferson, G. (1986). Notes on ‘Latency’ in overlap onset. Human Studies, 9(2–3), 153–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148125

- Karlbaugh, P. E., & Haviland, J. M. (1994). Nonverbal communication between parents and adolescents: A study of approach and avoidance behaviors. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 18(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02169080

- Kaukomaa, T., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2015). How listeners use facial expression to shift the emotional stance of the speaker’s utterance. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 48(3), 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2015.1058607

- Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Oxford University Press.

- Maynard, D. W. (2013). Defensive mechanisms: I-mean-prefaced utterances in complaint and other sequences. In M. Hayashi, G. Raymond, & J. Sidnell (Eds.), Conversational repair and human understanding (pp. 198–233). Cambridge University Press.

- Mondada, L. (2011). Understanding as an embodied, situated and sequential achievement in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(2), 542–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.08.019

- Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(3), 336–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.1_12177

- Ogden, R. (2013). Clicks and percussives in english conversation. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43(3), 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100313000224

- Ogden, R. (2020). Audibly not saying something with clicks. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 66–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712960

- Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Reber, E. (2012). Affectivity in interaction: Sound objects in english. John Benjamins.

- Ryle, G. (1971). ‘Thinking and reflecting’ and ‘the thinking of thoughts: What is Le Penseur doing? In Collected Papers II: Collected Essays 1929–1968. Hutchinson.

- Schegloff, E. A. (2005). On integrity in inquiry … of the investigated, not the investigator. Discourse Studies, 7(4–5), 455–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054402

- Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis, Volume I. Cambridge University Press.

- Shute, R., Owens, L., & Slee, P. (2002). You just stare at them and give them daggers: Nonverbal expressions of social aggression in teenage girls. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 10(4), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2002.9747911

- Sikveland, R. O., & Ogden, R. A. (2012). Holding gestures across turns: Moments to Generate shared understanding. Gesture, 12(2), 166–199. https://doi.org/10.1075/gest.12.2.03sik

- Stivers, T. (2004). “No no no” and other types of multiple sayings in Social Interaction. Human Communication Research, 30(2), 260–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00733.x

- Tomasello, M. (2008). Origins of human communication. MIT Press.

- Wright, M. (2011). On clicks in english talk-in-interaction. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 41(2), 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025100311000144