ABSTRACT

Through troubles-talk, participants disclose and negatively assess unfortunate past or habitual happenings and offenses, and these are often vividly staged in the here and now by temporarily “doing being” past Self or others, what we call animation. In this study, we show how by animating their own affective reactions toward the recounted experiences, tellers cast themselves as victims and their recipients as witnesses. More importantly, we demonstrate how animation is also a relevant practice for recipients, who in a contiguous position often offer a responsive co-animation of the same figure, validating and amplifying their teller’s affective displays, turning the experience into a common cause. This study contributes further to our understanding of empathic responses in troubles-talk in English by inscribing co-animation as a previously undescribed alternative at the response slot that allows recipients to temporarily position themselves “into the moment” as co-victims, co-experiencers, and co-sanctioners. Data are in English.

Among the many interactional activities that strengthen our relational bonds lies what is known as “troubles-talk”: “members’ talk about situations and events that are seen as distressful and disruptive of the routines of everyday life” (Jefferson & Lee, Citation1980, p. viii). Through forms of troubles-talk, participants disclose and negatively assess unfortunate happenings and offensive transgressions by absent others in more serious or lighthearted ways (Jefferson, Citation1984), discussing grievances and remedies (Emerson & Messinger, Citation1977; Schegloff, Citation2005), reporting affective reactions, and laying blame. Therefore, troubles-talk makes relevant a response with which co-participants can display empathy and negotiate shared values (Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2012; Mandelbaum, Citation1991; Pudlinski, Citation2005; Ruusuvuori, Citation2005; Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019; Traverso, Citation2009). The interactional study of troubles-talk spans a number of decades now, with research focusing on its sequential structuring as a specialized form of storytelling (e.g., Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2012; Heinemann & Traverso, Citation2009; Jefferson, Citation1988) as well as on the resources that tellers use to manage the moral matters that troubles-talk makes relevant (e.g., Dersley & Wootton, Citation2000; Drew & Holt, Citation1988; Günthner, Citation1997, Citation1999).

Central to our research is one specific practice that when deployed in troubles-talk in particular allows tellers to build an antagonistic frame (Günthner, Citation2000) by replaying “live” in the here and now their own experiences and feelings as victims of trouble. This practice will be here called animationFootnote1 (Cantarutti, Citation2020; Goffman, Citation1981) to incorporate the wide range of embodied ways in which participants can act as “sounding boxes” for the behavior of a figure (Goffman, Citation1981), temporarily and multimodally “doing being” past versions of themselves or absent others in the here and now of interaction.

We now turn to a first illustration of the phenomenon. In this excerpt, two friends discuss the challenges of long-distance relationships. At this point, Karen shares with her friend Angie the moment she announced to her mother that her boyfriend would be moving continents to be with her, animating their interaction in a somewhat “edited” form. Animated contributions are in bold:

Example 1.1. MCY07BOTTLE “Calm down” (GAT-2 Fine conventions)

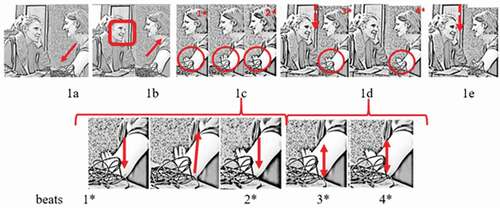

Karen prefaces the central part of her telling through a parenthetical remark (“mums are mums, aren’t they?,” line 4), a variation on an idiomatic expression that anticipates a critical stance, which is appreciated with a marker of recognition (“hm”) by Angie in line 6. The figure of the mother is brought to the here and now from Karen’s perspective (i.e., use of “we” and not “you” in “we’ll be settling down together,” line 8), designed with other embodied resources that simultaneously contextualize and recreate the mother’s enthusiasm (e.g., stylised/sing-song intonation, modalized voice, and swaying movement of the shoulders and head; see and multimodal transcription 1.1b) as well as Karen’s own overlaid mild disapproval of it. Angie displays recognition of this embedded criticism with a smile (line 8, ). The animation of the figure of the mother is followed by Karen’s self-animation of what she presents as a response to her mother’s reaction (“just calm down,” line 10), an appeal to caution produced with open palm beat gestures that further contextualize the idea of “slowing down” ()

.Example 1.1b. MCY07BOTTLE “Calm down” (Mondada Multimodal Transcription conventions; gesture marks: *Karen, +Angie)

This excerpt so far has illustrated how animation serves to enact sanctionable or unfortunate behaviors as well as the teller’s evaluative and affective reactions toward them, whether these were “silent thoughts” (Haakana, Citation2007) or actually uttered as such at the moment. Therefore, by demonstrating rather than describing (Clark & Gerrig, Citation1990), recipients are also cast as witnesses to the interactions being staged live through animation and are given access to internal processes of evaluation that allows them to “see for themselves” (Clift, Citation2006) how the grievance was committed and received. In this case in particular, Angie has been placed as a story recipient and witness to Karen’s version of the conversation between her and her mother and to Karen’s own critical response to the mother’s overenthusiasm.

Although past research on troubles-talk has described a number of ways recipients attend to the empathic affiliative concerns made relevant by these stories (Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2012; Heritage, Citation2011; Kupetz, Citation2014; Kuroshima & Iwata, Citation2016; Pudlinski, Citation2005; Selting, Citation2010, Citation2012), which may include co-complaining (Drew & Walker, Citation2009; Ogden, Citation2010), there are, to the best of our knowledge, no interactional studies specifically focusing on how animation can also be deployed to respond to troubles-talk. Indeed, our example has so far only shown part of Angie’s response: an agreement token (“yeah,” line 11) and nods () in overlap that acknowledge and recognize the issue that Karen’s story put forward. In fact, if we reveal the rest of Angie’s response, we can identify a special form of demonstrating understanding, agreement, and validation of Karen’s criticism:

Example 1.2. MCY07BOTTLE “Calm down”

Angie co-opts the voice of Past Karen addressing the absent figure of the mother (lines 12, 14), “doing being” Past Karen through the lexical and prosodic repetition of Karen’s animated content (“calm down,” line 12) and extending the animated response to the mother with a reformulated version that unpacks the meaning of “calm down” (“don’t get too ahead of yourself,” line 14). Angie is not now offering a response from her external role as a witness but actually joins in Past Karen’s reaction to the mother’s incautious enthusiasm as if she was Past Karen in that situation, while affiliating with her in the here and now. In other words, Angie responds by co-animating (Cantarutti, Citation2020; cf. voiced direct reported speech as a form of resonance, Niemelä, Citation2011; echo reported speech, Guardiola & Bertrand, Citation2013) the same figure.

This study therefore focuses on a previously unstudied phenomenon within troubles-talk: the deployment of co-animation (i.e., the joint animation of a figure in an interactionally contiguous position) and its role in managing the moral and affiliative concerns that troubles-talk makes relevant. We first show how at specific points in the telling sequence, by bringing in the voices of transgressors (where relevant) as evidence, but primarily by animating their own affective responses to offenses or misfortune, tellers present themselves as victims of some sort. Centrally, we focus on responsive co-animation: a practice by which recipients interactionally cast as witnesses to a teller’s situation and feelings of victimhood, and whose next relevant thing to do is to display some form of affiliation, actually empathetically insert (Goffman, Citation1974) themselves onto the described experience. Co-animators temporarily get in the victim’s shoes becoming “sounding boxes” for the affective displays of their co-participants, amplifying them. The aim of this article will be to expand on existing conversation-analytic descriptions of repertoires of empathic responses to troubles-talk by incorporating responsive co-animation as a different type of “into-the-moment” (Heritage, Citation2011) response that allows recipients to momentarily act as if they were co-victims responding to the experience or transgressor, as co-experiencers of the affective issues that such troubles make relevant, and as co-sanctioners of the type of behavior and disruption that the stories have foregrounded.

The next section explains the data and methods used, followed by a brief literature review on the interactional demands of troubles-talk and what we know about empathic responses to contextualize our contribution. The central part of this article analyzes the deployment of first animations in climactic moments of troubles-talk and the empathic role of responsive co-animations, with which co-participants adopt a co-victim/-experiencer/-sanctioner status. The final sections reexamine the findings by describing some of the affordances of co-animation as a response and discuss the role of co-animation in the interactional building of temporary common causes.

Data and methods

This study adopts the methodological tools of conversation analysis (Sacks et al., Citation1974; Schegloff, Citation2007) and a multimodal approach to interactional linguistics (Couper-Kuhlen & Selting, Citation2001) to the analysis of 37 episodes of first + responsive animation in troubles-talk between friends, relatives, or coworkers, plus eight cases where the response to a turn containing a first animation is not co-animated. The data are part of a larger collection of 89 cases of co-animation identified in different types of social activities (troubles-talk, teasing, and joint fictionalization, see Cantarutti, Citation2020) from 10 hours of video-recorded face-to-face interaction in English in two corpora (MCY: Cantarutti, Citation2018; RCE: Rossi, Citation2011). The study received ethical clearance from the University of York, and participants offered their informed consent for the recording and use of their anonymized data for publication.

The collection discussed in this article features the co-animation of the same figure in contiguous positions (i.e., first animation + responsive co-animation) in troubles-talk. As previously shown, animation is here understood as a way of (non-)verbally “doing being” a figure (a past or fictional version of oneself or others) and embedding a new interaction within the current interaction, bringing about temporary changes in participation frameworks (Goffman, Citation1981) in the here and now. The hearability of animation as such hinges partly on its design, which includes deictic elements (pronouns, demonstratives) anchored in a time and/or space displaced from the here and now, the use of quotative prefaces (e.g., be like, say), as well as noticeable shifts away from modal voice and posture and disjunctive gestural trajectories (Cantarutti, Citation2020). Moreover, participant orientation to animated turns reveals that the content per se is indeed understood as addressed to an absent third party, while what gets responded to is the action made relevant by the deployment of animation in the here and now (e.g., complaining). Responsive co-animation has been operationalized as a contribution adjacent to a first animation where a co-participant is “doing being” the same figure, traceable through the format-tying of lexicogrammatical, prosodic, and/or gestural design elements to those of the first animation. These contributions are more generally oriented to by first animators through a form of acceptance, appreciation, or agreement in third position.

In 36 of the cases of the collection the co-animated figure is a past version of the teller, the remaining case being a joint animation of a controversial politician. These were contrasted with the only eight cases found in the corpus where a first animation of the figure of the teller was present, but the response was not co-animated. The vast majority (n = 29) of troubles recounted were experienced firsthand by the teller only. Due to space constraints, the analysis developed here will be restricted to those cases only, with comparative remarks with the other subset included where appropriate.

The article incorporates multimodal analyses to prove how participants make (co-)animation visible and hearable as such to each other and how they overlay a stance onto the animated content. The registering of phonetic detail involved an impressionistic parametric analysis (Local & Walker, Citation2005) supplemented with instrumental measurements for validation and visualization in Praat (Boersma & Weenink, Citation2016). The annotation of gestural phases and trajectories in ELAN (Brugman & Russel, Citation2004) followed the considerations summarized in Ren-Mitchell (Citation2018). Transcriptions follow GAT-2 (Selting et al., Citation2011) and Mondada (Citation2016) conventions, with greater detail offered only where required by the analysis. Animated contributions appear in bold.Footnote2

Troubles-talk and empathic responses

Our study involves the analysis of co-animation in different forms of troubles-talk. To make sense of the deployment of first animations and especially of responsive co-animations, it is necessary to review some of the structural, affiliative, and moral issues these telling activities of unfortunate happenings and/or offenses make relevant.

Troubles-talk can be a delicate activity, even when it is often done in a lighthearted way. Firstly, it entails making an issue in a participant’s intimate sphere open for public scrutiny (Drew, Citation1998; Emerson & Messinger, Citation1977). The delicacy of this disclosure and any moralizing that results from it are often interactionally managed by the setting up of an antagonistic frame (Günthner, Citation2000) involving (strong or mild) misfortune, grievances, or a sense of conspiracy that we could unpack as one of “I vs. trouble,” or in the case of complaint stories, “I vs. transgressor.” This dramatic scene is made vividly present and evident in the here and now through a number of resources and practices by which the recipient is cast as a witness to the teller’s victimhood, one of which is animation, through which past scenes and affective states are multimodally staged rather than just described.

Moreover, tellers also manage these issues by developing their stories in a stepwise way (e.g., Drew, Citation1998; Jefferson, Citation1988; Selting, Citation2012; Traverso, Citation2009). Troubles-talk begins with preparatory stages where tellers build their case, constructing shared epistemic (Raymond & Heritage, Citation2006) and affective ground (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2019) and creating a “safe space” for disclosures and affiliation to develop. Troubles-talk is generally done as a “series” with increasing levels of explicitness and the escalation of retold grievances toward stronger pursuits of affiliation until closure is jointly achieved (Jefferson, Citation1988). The climactic part of the telling is the point where tellers reach a peak of not only the relative seriousness of the events but also of affectivity (Selting, Citation2010). This is where affiliation takes precedence, with each new contribution building a “recognisable bid for empathy” (Hoey, Citation2013, p. 5) and marking as a relevant next a congruent empathic response that validates the affective reactions to the reported trouble. Interestingly enough, this is the locus of first animations and responsive co-animations in our collection.

Prior research on institutional and ordinary conversation has described a range of possible empathic responses that co-participants offer at these points in troubles-talk, as well as problematizing some of the affiliative and epistemic issues they involve (e.g., Heritage, Citation2011; Hepburn & Potter, Citation2007; Kupetz, Citation2014; Kuroshima & Iwata, Citation2016; Pudlinski, Citation2005; Ruusuvuori, Citation2005; Selting, Citation2010, Citation2012). Empathic responses are said to display or even demonstrate not only intersubjective understanding of the situation described but also some degree of experience of the emotional state that particular negative situations trigger (Heritage, Citation2011). Past research on empathic responses, however, claims that demonstrating knowledge at this point after a delicate disclosure of someone else’s troubles is interactionally problematic. On the one hand, for the response to be affiliative it should constitute a form of independent agreement by which recipients are not seen to be “merely going along” with the teller (Raymond & Heritage, Citation2006, p. 695), while on the other hand they should not be overengaging to the point where they may be treated as “appropriating” (Raymond & Heritage, Citation2006, p. 701) the experiences disclosed. Nevertheless, as we will reveal, co-animation as a practice offers some new insights around the social acceptability of interactionally co-constructing and co-owning experiences, particularly as we will show how responsive co-animation involves enacting displays of shared affectivity to orient to experiences recipients may not have had firsthand themselves.

Heritage (Citation2011) and Kupetz (Citation2014) each propose an ordering and a “menu” of empathic response types. Kupetz’s study focuses on the characteristics of empathic responses relative to their length and where in the telling they are deployed. Her study explains how early in the telling co-participants tend to offer “fleeting” responses (e.g., facial expressions, response cries, candidate understandings), while later orienting to the pressing affiliative concerns of climactic moments by providing “more substantial” responses (expressions with mental verbs, formulations, second stories). These findings are relevant for our later claim that co-animation makes for a “substantial” type of response in both length and degree.

Heritage (Citation2011) has found that responses to personal experience could be placed along a continuum going from more detached and nonempathic types (e.g., ancilliary questioning, parallel assessments) toward equally independent but more involved “into-the-moment” empathic responses (subjunctive assessments, observer accounts, response cries). Of particular interest to our work is Heritage’s category of “observer responses” by which recipients “claim imaginary access to the events and experiences described, but position themselves as observers, or would-be observers to the event” (p. 171). Through these practices in particular, recipients position themselves as wishful witnesses (as in the response “God I wish I could see his face” to an “agonistic experience” reported in Heritage, Citation2011, p. 172) or as make-believe observers whose contribution is framed as if watching the teller at the time of the experience (e.g., “I can see you two kids!,” Heritage, Citation2011, p. 171). Our major contribution in this article will be to prove how through responsive co-animation recipients also get “into the moment” but they surpass this observer/witness role to actually cast themselves as co-victims and co-experiencers by “doing being” their co-participants and co-sanctioning any transgressors where appropriate.

The next sections will offer an in-depth analysis of our collection in a way that establishes a conversation with these prior studies to explain how responsive co-animation constitutes a new special addition to this menu of “into-the-moment” and “substantial” empathic responses at moments of peak affectivity in troubles-talk.

Responsive co-animations: from witnesses into co-victims, co-experiencers, and co-sanctioners

In this section we will show first how through a cluster of resources and practices including animation, troubles-talk recipients are cast as witnesses to (often nonserious) recreations of negative happenings or offenses. Tellers reach their story climaxes by offering a self-animation of their (past or reconstructed) affective response to the trouble or transgressor, making an affiliative response relevant. Moreover, and fundamentally, this section will demonstrate how, given a relevant-next display of understanding and empathy, recipients may continue these affect-laden animations of the figure of the tellers, empathetically inserting themselves “into-the-moment” as if they were co-victims, co-experiencers, and/or co-sanctioners.

One of the ways in which tellers create a witness status for the recipient is by providing epistemic access (Heritage, Citation2012) to the trouble and to any affective reactions to it with great levels of granularity so that recipients can “see for themselves” what it was like to experience the trouble/offense. This is done through a number of resources that objectify the experience for joint assessment (Edwards, Citation2005), including extreme case formulations (Pomerantz, Citation1986), idiomatic expressions (Drew & Holt, Citation1988), and forms of “overdetermination” of action (Drew, Citation1998, p. 318) among which lies animation, contextualized through gestural and nonmodal prosodic features (Cantarutti, Citation2020; Günthner, Citation1997, Citation1999). In turn, co-animation as a response, it will be shown, orients to these forms of dramatic and granular representation through design features that format-tie to prior animations and further contribute to maintaining the antagonistic frame.

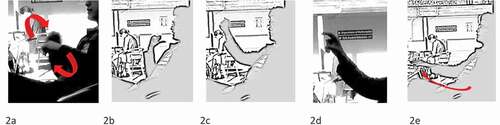

Our next excerpt shows how animation and other resources are recruited to create access not just to a troublesome event and its “precipitating circumstances” (Couper-Kuhlen, Citation2012) but also to what it is like to have experienced them, something that the story recipient is invited to appreciate empathetically as a witness and which will be finally validated through responsive co-animation. Jon is telling his friend Dan about his experience at a drama camp in the United States, where he was in charge of setting up the whole sound and lighting system for a show in a shed with only two power outlets. This lengthy 5-minute story is set up as a series of worsening infrastructure difficulties that Jon sorts out with heavy-duty activities involving long extension cables (not shown). These handyman tasks are now listed, embodied with wide gestural trajectories (lines 53–56) and vivid representations (). Dan has so far displayed active listenership, engaging empathetically at relevant points and assisting the telling during word searches. The story has now reached a key point where the previous difficulties described in the story are to be seen by Dan in the light of an even greater form of trouble experienced by Jon, a “really shitty back and shoulder” (lines 57–58, 60), made worse by a thin and bad-quality mattress (lines 61–63), whose description and assessment are also accompanied with a gestural demonstration ()

.Example 2.1. MCY02BAR “Cause I’m dying” (Gesture marks: *Jon, +Dan)

So far the story design has revealed a lot of work on the part of Jon to illustrate and give access to the kind of strain he was in. The back pain is visibly topicalized with a held pointing gesture toward his back (lines 57–60, ) and is recycled with a lexical repetition (line 60). Dan mirrors these efforts by vigorously shaking his head and nodding (lines 57, 62–63) at the right places and ostensibly “doing remembering” in line 59, revealing his recognition and access to Jon’s back pain and initiating and then abandoning a display of empathy (“you must’ve … ”), an into-the-moment observer report.

Now that the pain has been topicalized as the central trouble in the story and a form of empathy has been offered by the recipient, Jon conveys the extent of his pain and urgency by referring to the remedy he had to seek: having to see a nurse to request physio exercises and painkillers (lines 67–73). Upon Jon’s mention of the nurse, Dan now offers another fleeting empathic response (“a::w,” line 70).

Example 2.2. MCY02BAR “Cause I’m dying” (Gesture marks: *Jon, +Dan)

Jon makes his animation of the interaction with the nurse hearable as such, first, with the quotative preface “be like” (line 69). The animation is formulated as a request addressed to the nurse formatted in a highly entitled manner (“and just give me a load of painkillers,” line 72), which may not have been part of the original formulation (see Holt & Clift, Citation2007, on speakers’ licenses when reporting talk). Moreover, the embodiment of the painful back has been framed somehow iconically, that is, in ways that symbolically represent Jon’s sensation of stiffness and pain, in this case through limited gestural movement and minimal prosodic variation during the animation. Jon’s speech hovers minimally above and below his pitch range midline (see , below). A noticeable change in posture () also occurs, with Jon leaning forward and sitting up straight, after saying “put my back out” (line 66), keeping his rigid posture throughout the animation and starting the retraction as the word “painkillers” is uttered (line 72). These embodied contextualizing features deployed by Jon contribute to the provision of evidence for Dan to see for himself how taxing the handyman tasks would have felt for Jon in his condition and how serious it became.

Figure 4. Visualization of contours of Jon and Dan’s co-animated segment (midline estimated for Jon, Dan’s midline estimated to be only 3 Hz lower).

Dan’s active listenership at this point is exercised first by his sustained mutual gaze and with recognitional nodding (line 72; cf. Angie’s head nods in “Calm Down”) before responding in co-animation. Dan’s co-animated version (“cause I’m dying,” line 74) orients to several aspects of the design of Jon’s action. His other-continuation (Sidnell, Citation2012), a “(be)cause-prefaced” TCU, starts a subordinate clause that is fitted to the ongoing grammar in Jon’s turn. Dan’s production is also prosodically integrated (Auer, Citation1996; Figure) to Jon’s animation: his animated segment starts noticeably lower in pitch than Jon’s finishing pitch for “painkillers,” a phenomenon that has been described for self-increments (Walker, Citation2004).

In terms of action, Dan’s version initiates an account on Jon’s behalf (with “I’m” ascribable to Past Jon), formulated in a way that embodies a justification for the request while conveying Jon’s extreme pain and urgency as if co-experiencing it, which is explicated through hyperbolic phrasing (“dying”). Thus, Dan is seen to have momentarily moved away from his witness role into a co-victim one, getting “into the moment” and in Jon’s shoes. This is followed by a latched change of footing from his “doing being” Jon as a joint animation figure, back into his own “witness” role again with a more canonical non-animated type of recipient response (“yeah,” line 75). Dan’s co-animation is treated by Jon as an appropriate understanding of his past state (“yeah,” line 76), retrospectively marking the resulting co-animated contribution as successful (see also “exactly” in Example 1.2), the most frequent outcome in the collection.

We have so far shown the embodied efforts of tellers in conveying the circumstances leading to the trouble/complainable as well as the multiple forms of involvement of recipients, with early markers of recognition and affiliation throughout, toward more “substantial” empathic responses. Responsive co-animations, we have seen, take up the voice of a figure ascribable to a past version of the teller and continue the animation of the behavior or affective reaction that tellers started at the peak of troubles-talk. Thus, recipients act as co-experiencers of those feelings, and in so doing, they simultaneously endorse their teller’s (re)action in the face of trouble.

In our next example, as in other cases of the collection, the first animation of Self is preceded with an animation of the transgressor (e.g., the mother in “Calm down”). However, across our collection, the jointly animated figure is almost unexceptionally that of the past version of the teller. In any case, the animation of the transgressor is relevant to our understanding of the moral matters that co-animation makes relevant, as tellers do moralizing (Heinemann & Traverso, Citation2009) by ascribing blame to these figures and thus revealing what they take to be normative, that is, the values that they uphold and that have been violated. Therefore, tellers position themselves as victims but also as sanctioners in animating the critical behavior of others as well as their affective responses to it, and responsive co-animators “doing being” the Past versions of the tellers will therefore be seen to be joining in this moralizing and antagonistic experience.

The next example shows how recipients can also become co-sanctioners, even in lighthearted condemnation of third parties. Jesse asks his colleague Fiona whether publications on the academic magazine she edits are citeable (not shown). He uses this initial request for confirmation to launch troubles-talk on the problems he is encountering with his papers, something he initially assesses as worrying and annoying (lines 8–9). He explains he cannot condense all the necessary information into a single paper (lines 8–11), so he has written his articles as a series, which creates a word-limit problem when contextualizing each study (lines 14–18).

Example 3.1. MCY04SANDWICH “Page limit” (Gesture marks: *Jesse)

Fiona initially orients to Jesse’s explanation of the nature of the problem with interspersed recognitional receipt tokens (lines 13, 16, 19). After a (potential) sequence-closing assessment (“annoying,” line 22) by Jesse, Fiona offers an extended supportive response that demonstrates her independent knowledge of these matters (lines 21, 23, 24–26, 28–33) in a way that legitimizes Jesse’s practice of writing papers serially as a usual thing in academic culture. This is already a substantial response in terms of empathy, and one that seems fitted to the climax of troubles-talk. Even though Jesse agrees verbally early on (line 27) and nods throughout (lines 25, 28, 32), he does not offer an agreement token at the end of Fiona’s account.

Indeed, Jesse’s initially described issue is not the crux of his conundrum, and as in prior cases, after having secured empathetic responses, tellers offer stronger or more granular versions of the trouble. As a response to this extended affiliative effort by Fiona, Jesse reintroduces both the previously mentioned serial and page limit problems (line 11–18), moving from their shared academic experience into his personal sphere again, this time incorporating his supervisor’s criticism around this matter (lines 34–38). Jesse’s problem as defined by the supervisor runs counter to Fiona’s claim that “some papers are meant to be read as a series” (lines 32–33), and Jesse uses this slot to reorient the definition of his troubles and topicalize the complaint toward his supervisor.

The figure of the critical supervisor is now animated as carrying out two actions: first a reprimand (lines 36–38) and then a set of contradictory and unhelpful directives (lines 40–41). These are mediated by interspersed commentary by Jesse-as-teller anchored the here and now (“and then at the same time,” line 39). The supervisor figure is then addressed by a Past Jesse figure producing an exasperated reaction to such feedback (line 43), framed as nonserious with interspersed and post-positioned laughter (Jefferson, Citation1984)..

Example 3.2. MCY04SANDWICH “Page limit” (Gesture marks: *Jesse)

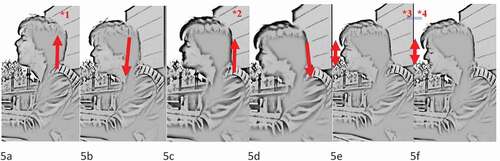

As with prior cases, this animated contribution is not necessarily anchored in the same there and then as the complainable, as this response may not have been uttered to the supervisor in this way but is, rather, a possibly reconstructed affective display (Selting, Citation2010), contextualized by rhythmic scansion (i.e., proximity of strong accents, see also “Calm down” Example 1.1b) with head beat gestures ()

that normally accompany displays of indignation (Cantarutti, Citation2020; Günthner, Citation1997).Fiona snorts in response (lines 42, 44), appreciating the animated mock despair, and then offers a co-animated version (“do you understand how page limits work?,” line 46) of Jesse’s complaint addressed to the supervisor, taking up Jesse’s initial page limit trouble and unpacking the criticism of the supervisor’s unhelpfulness implied in Jesse’s first animation. It also shares Jesse’s dense accentual prosodic design and the pitch contour deployed (see ). As in previous examples, the story recipient is seen to be jointly enacting the victim figure in response to the offender and, in that way, offering validation as they team up against the now jointly sanctioned behavior of the transgressor.

Figure 6. Visualization of contours (scaled to speaker’s ranges with midline) and time intervals between accented syllables in the co-animated contributions (left, Jesse; right: Fiona).

Our final example of co-animation provides further evidence for the recipients’ positioning as co-experiencers and co-victims to some form of (jocularly presented) wrongdoing and also demonstrates how co-animators jointly sanction transgressors on the basis of their interactionally built epistemic and affective grounding irrespective of any prior access. Dan is telling Jon about his former favorite YouTuber, a young woman who used to get drunk and cook on camera (not shown). Jon has not watched the channel himself, but upon hearing Dan’s adumbration of the complaint (“she used to be great …,” lines 17–18) he offers a candidate assessment for the complaint (line 20). This is rejected by Dan, explaining at length that the problem is that she now promotes mindfulness and does not get drunk anymore (lines 21–30, some omitted). After Jon’s misapprehension in anticipating the crux of the trouble,Footnote3 Dan topicalizes the complaint (line 30), receiving from Jon a matching “exasperated” response (line 32), a highly audible sigh. In a similar way to our prior examples, after trouble has been topicalized and a form of empathy has been provided, a first animation is introduced. Dan produces a quotative preface (line 34) and begins his self-animation of his role as viewer, first nonverbally by hitting his fist on his lap repeatedly (line 34, )

and then verbally addressing the complaint to the YouTuber regarding her lack of public drunkenness (lines 34–35).Example 4. MCY02BAR “Wasted” (+Dan, *Jon)

In recognitional overlap, Jon joins in, getting “into the moment” through a co-animation that also rejects the transgressive behavior described. Jon’s version is lexically upgraded (“drunk,” line 35 > “wasted,” line 37), including the provision of an example of the kind of behavior expected of the YouTuber (lines 39–40), revealing his understanding of the show’s valued entertainment content, which Dan endorses with several “yeah” tokens (lines 38, 41). As in our prior examples, Jon does co-complaining on Dan’s behalf (and presumably also representing a collective of viewers), in spite of not having firsthand experience of the show. In this way, Jon is seen to be teaming up with Dan in a complaint directed to the absent YouTuber, no longer positioned as a witness to Dan’s indignation but actively acting as a playful co-sanctioner and co-indignant watcher.

This section has focused on co-animation as a means of jointly managing the affiliative, moralizing, and antagonistic aspects involved in troubles-talk. We claimed that through the evidence provided throughout the story, and particularly at climactic points through a first animation, tellers interactionally construct their story recipients as witnesses to their own antagonistic experience and victim status against currently absent but invoked troubles or transgressors. Animation has been found to facilitate this interactionally achieved co-experiencing, since as Goffman (Citation1974) put it, “a replaying will therefore, incidentally, be something that listeners can empathetically insert themselves into, vicariously reexperiencing what took place” (Goffman, Citation1974, p. 504). Responsive co-animation, we have shown, is one such way in which recipients can enact their empathetic insertion into the experience and the feelings it can engender.

The next section will revisit some of these findings in the light of the literature previously reviewed on empathic responses and will briefly discuss some of the affordances of responsive co-animation versus other alternatives found in the same sequential slot.

Co-animation as an empathic response

In previous sections we reviewed prior studies on empathic responses in troubles-talk, and we claimed that co-animation is a hitherto unstudied form of empathic response. Co-animation makes for a literal form of empathetic insertion, as recipients respond by getting “into the moment” by “doing being” the figures of the tellers affectively reacting to these troubles. We here discuss some of its affordances as evidenced by our analyses.

Our study reveals that an important part of offering access to recipients to what it was like to have experienced these troubles is through multimodal self-animations that enact a reconstruction of affective states. These are presented as if currently addressing the transgressors or a relevant absent party in the here and now, providing access to “what went on in the narrator’s mind at the specific point of the narrated interaction” (Haakana, Citation2007, p. 153), without any claims of these having been actually uttered—at all, or in that way. This fuzziness proves facilitative for incipient co-animators, who irrespective of their initial epistemic standing regarding the events recounted, eventually receive confirmation in third position of the appropriateness of their co-animated contributions. What is more, co-animation is facilitated through the reflective objectification that animation as a practice entails, in that it “loosens the bond” (Goffman, Citation1974, p. 541) between the current and past versions of Self, making the speaker also an evaluative observer of their Past Self in the extended action of telling.

Cases like “Calm Down,” “Cause I’m Dying,” “Wasted,” or “Page Limit” show how responsive co-animation provides co-participants with an opportunity to treat affective responses to events that have not been experienced in their particulars to become co-owned and validated as reasonable and shared. Responsive co-animation shows that any initial epistemic differentials can be sidestepped for all practical purposes in the here and now of the interaction, as it involves the enactment of a recipient’s understanding of what a relevant empathetic response to a particular situation would be, that is, of “what it would be like and how a co-participant might experience it” (Hoey, Citation2013, p. 2). Therefore, our research shows how responsive co-animation challenges some of the constraints prior work has described around epistemic ownership, as it creates opportunities for reciprocal affiliation beyond any strict territorial preserves (Goffman, Citation1971). Even when they do not share strict firsthand access, responsive co-animators make a bid to become co-experiencers, that is, to have their own understanding of the troubles (possibly also by analogy to their own experience) count as a joint response to the described troubles, piggybacking on the reaction offered initially by tellers. In this way, producers of co-animated responses go beyond the “observer” type that Heritage mentions in his “into-the-moment” empathic responses to instead enact, temporarily, an empathic and endorsing reaction as if literally in the teller’s shoes.

A final question to answer is how co-animation fares in comparison to the other alternative forms of empathic displays found in our collection of animation in troubles-talk, where only less than a fifth of cases lack a co-animated response. These eight cases also follow the structure of [(animated transgressor) + animated (affect-laden) response to trouble/transgressor/relevant party] at the story climax but feature one of the other kinds of responses reviewed earlier in the literature—namely, independent assessments, “yeah” agreement tokens, gist formulations, laughter, and second stories. These alternative response types also display understanding and affiliation but do so from an external and independent perspective, assessing the story in more canonical and witness-like ways that do not encroach into the teller’s own particular experience.

The following example shows a non-co-animated response to a first animation. Unlike what we found in our prior co-animation cases, we here see the co-participant assessing the figure of the transgressor rather than co-animating the affective reaction of the teller. Maddy has been complaining about her flatmate Cath to her friend Katy and now launches a new telling as evidence of Cath’s lack of receptiveness, presented as an account to reject Katy’s proposed solution to the rift (lines 3–4). Maddy offers detailed animated dialogue, including the animation of the flatmate (lines 23, 28) and then a self-animation of a (real or reconstructed) response to her (“bye, then,” line 31). This is a slot (lines 32, 33) where Katy could have responded in co-animation, given our prior configuration. Instead, she produces an agreement token (line 32), followed by an assessment that characterizes and evaluates the transgressor’s behavior (line 34).

Example 5. MCY0GEESE “Defensive”

There is no evidence of a pursuit of co-animation as a suitable response by Maddy through, for example, further self-animation. It is noteworthy, though, that Maddy responds to Katy’s assessment through a non-animated version of her own reaction (“It’s not like I can … I’ve nothing to say, then?” lines 35, 37), unpacking the stance of helplessness in her prior self-animation (“okay, bye then!,” line 31) but also tying back to her initial rejection of Katy’s conciliatory proposal (line 7). Interestingly, this non-animated redoing of her reaction (lines 35, 37) as a response to Katy’s appreciation shows how the climactic stages of troubles-talk seem to create slots for empathic responses where what is primarily relevant is the validation of the teller’s own (affective) reactions to trouble or offense. In fact, this is what Maddy leaves on record at the end of her telling. This could explain the high frequency of co-animation of the affect-laden response of the teller figure in the collection instead of that of the transgressor.

However, in spite of its wide distribution in the collection, responsive co-animation cannot readily be pronounced as the preferred answer to first animations, given that none of the non-animated responses in these cases are sanctioned, nor do they feature markers of dispreference. Similarly, when deployed, as we have seen, responsive co-animation is not produced with markers of dispreference either, and it is rarely explicitly initiated repair on. Consequently, it could be asked what opportunities responsive co-animation offers in relational terms to participants in the development of this delicate social activity of troubles-talk when other independent, non-territorially-invasive options are available.

By co-animating and addressing an absent offender or trouble in a joint antagonistic way, a co-animator provides an affiliative response that in terms of degree, length, and involvement matches the granularity efforts and the stance projected throughout the story. Therefore, a co-animator is also speaking as the first animator while making a bid to speak on their behalf against this absent party/position or as part of a collective that may involve both the teller and themselves—which is seen in the cases where there is greater epistemic symmetry. Recipients literally empathetically insert themselves, turning what was once a personal and intimate matter into a common cause. By presenting their responses as if they were experiencers of the very same trouble in the very same situation, troubles-recipients normalize and validate the affective reactions that first animators have reported of themselves. These troubles are then not treated as if they were an individual experience alone but rather one that others associating with this animated figure could reasonably experience in this way as well.

Moreover, many of these presumably “edited” or “silent” criticisms (Haakana, Citation2007, p. 160) that are part of the affective response being animated are presented as displays of indignation and discontent that may not have been uttered in that way, or at all, in the actual situation narrated. By selectively reconstructing the antagonism in the here and now and inviting the recipient to witness it, tellers are offered a new possibility to not only get it off their chests but also have a go at receiving the validation, and even defense, that may have been absent in the teller’s original experience of a trouble. Co-animators join in the “condemning game,” enacting rather than describing their shared understanding of what is a valid reaction to such a disruption of social norms (Günthner, Citation1997). As a result of these “into-the-moment” empathetic insertions leading to a “human fusion” into joint victims, experiencers and sanctioners, tellers end up with a stronger and collective version of Self as part of their front against the troubles or offenders faced in and through the telling.

Concluding remarks

This study has zeroed in on the previously undescribed practice of co-animation as it occurs at climactic points of troubles-talk to demonstrate how it offers co-participants an option to provide unique forms of empathetic insertion and affiliation around jointly negotiated affective and reasonable ways of assessing and reacting to trouble.

In the here and now of troubles-talk, tellers invoke the behavior of absent third parties as transgressors or the trouble as an entity, which they confront as if currently present, thus interactionally staging a form of antagonism. The animations introduced provide recipients with access to something that is central to the activity of troubles-talk: a “feel” of what it was like to be on the victim end of a particular negative experience. Co-participants are thus interactionally cast as witnesses to situations of vulnerability and victimhood experienced by the tellers and are invited to affiliate empathetically.

Within the menu of forms of orientation to troubles-talk, responsive co-animations provide an empathic response that resonates with the “into-the-moment” responses described in Heritage (Citation2011). However, instead of positioning themselves as observers, responsive co-animators instantiate their empathetic insertion (Goffman, Citation1974) and endorsement by literally “doing being” the figure of the teller, by embedding themselves in the there and then of the animation speaking on their co-participant’s (and possibly their own) behalf, making use of their own experience coupled with the epistemic and affective ground constructed earlier in the telling.

By co-animating a figure in a responsive slot and thus extending and amplifying the teller’s reconstructed affective response to their troubles, recipients recast themselves, albeit temporarily, as co-victims, co-experiencers, and co-sanctioners, validating and co-owning their teller’s victim response and thus turning personal matters into public common causes. By literally getting in the victim’s shoes for a moment, co-participants associate around a shared stance, using the social activity of troubles-talk to “team up” as a joint front of like-minded individuals against offenders or situations deemed transgressive or harmful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Even though the limitations of Goffman’s production role model are acknowledged (e.g., Goodwin, Citation2007), the label animation was selected to refer to this practice because it does not commit to any one modality (vs. reported “speech,” see, e.g., Coulmas, Citation1986) or to any claims of verbatimness (e.g., “quotation”), and it foregrounds the “doing being” and “sounding box” side of the practice that allows us to focus on the meaningful ways speakers interlace the needs of the here and now with the animated content and figure (see Cantarutti, Citation2020).

2 The boundaries of animated segments are not always smoothly delimitable (especially when nonvocal behavior is concerned), and thus some contributions remain ambiguous and probably functionally so (Cantarutti, Citation2020).

3 This is not explored further in this article as it is not exclusive of troubles-talk, but future work will explore co-animation in repairing recipient-teller misalignments.

References

- Auer, P. (1996). On the prosody and syntax of turn-continuations. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & M. Selting (Eds.), Prosody in conversation: Interactional studies (pp. 57–100). Cambridge University Press.

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2016). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.1.27) [ Computer program].

- Brugman, H., & Russel, A. (2004). Annotating multi-media/multi-modal resources with ELAN. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’04). European Language Resources Association (ELRA). http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2004/pdf/480.pdf

- Cantarutti, M. N. (2018). MCY corpus of English interaction [ Dataset]. University of York.

- Cantarutti, M. N. (2020). The multimodal and sequential design of co-animation as a practice for association in English interaction [PhD]. University of York. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/27344

- Clark, H. H., & Gerrig, R. J. (1990). Quotations as demonstrations. Language, 66(4), 764–805. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/414729

- Clift, R. (2006). Indexing stance: Reported speech as an interactional evidential. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 10(5), 569–595. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2006.00296.x

- Coulmas, F. (1986). Reported speech: Some general issues. In F. Coulmas (Ed.), Direct and indirect speech (pp. 1–28). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., & Selting, M. (2001). Introducing interactional linguistics. In M. Selting & E. Couper-Kuhlen (Eds.), Studies in interactional linguistics (pp. 1–22). John Benjamins Publishing.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2012). Exploring affiliation in the reception of conversational complaint stories. In M. Sorjonen & A. Peräkylä (Eds.), Emotion in interaction (pp.113–146). Oxford University Press .

- Dersley, I., & Wootton, A. (2000). Complaint sequences within antagonistic argument. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 33(4), 375–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3304_02

- Drew, P. (1998). Complaints about transgressions and misconduct. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 31(3–4), 295–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.1998.9683595

- Drew, P., & Holt, E. (1988). Complainable matters: The use of idiomatic expressions in making complaints. Social Problems, 35(4), 398–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/800594

- Drew, P., & Walker, T. (2009). Going too far: Complaining, escalating and disaffiliation. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(12), 2400–2414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.046

- Edwards, D. (2005). Moaning, whinging and laughing: The subjective side of complaints. Discourse Studies, 7(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605048765

- Emerson, R., & Messinger, S. (1977). The micro-politics of trouble. Social Problems, 25(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/800289

- Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. Harper & Row.

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

- Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Goodwin, C. (2007). Interactive footing. In E. Holt & R. Clift (Eds.), Reporting talk: Reported speech in interaction (pp. 16–46). Cambridge University Press.

- Guardiola, M., & Bertrand, R. (2013). Interactional convergence in conversational storytelling: When reported speech is a cue of alignment and/or affiliation. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 705. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00705

- Günthner, S. (1999). Polyphony and the “layering of voices” in reported dialogues: An analysis of the use of prosodic devices in everyday reported speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 31(5), 685–708. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)00093-9

- Günthner, S. (2000). Constructing scenic moments: Grammatical and rhetoric-stylistic devices for staging past events in everyday narratives. Interaction and Linguistic Structures (InLiSt), 22. http://kops.uni-konstanz.de/handle/123456789/3709

- Günthner, S. (1997). The contextualization of affect in reported dialogues. In S. Niemeier & R. Dirven (Eds.), The language of emotions: Conceptualization, expression, and theoretical foundation (pp. 247–276). John Benjamins Publishing.

- Haakana, M. (2007). Reported thought in complaint stories. In E. Holt & R. Clift (Eds.), Reporting talk: Reported speech in interaction (pp. 150–178). Cambridge University Press.

- Heinemann, T., & Traverso, V. (2009). Complaining in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(12), 2381–2384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.10.006

- Hepburn, A., & Potter, J. (2007). Crying receipts: Time, empathy, and institutional practice. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 40(1), 89–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701331299

- Heritage, J. (2012). Epistemics in action: Action formation and territories of knowledge. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 45(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.646684

- Heritage, J. (2011). Territories of knowledge, territories of experience: Empathic moments in interaction. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 159–183). Cambridge University Press.

- Hoey, E. (2013, June 25–29). Empathic moments and the calibration of social distance [ Paper presentation]. International Conference on Conversation Analysis, Los Angeles, CA.

- Holt, E., & Clift, R. (Eds.) (2007). Reporting Talk: Reported speech in interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Jefferson, G. (1988). On the sequential organization of troubles-talk in ordinary conversation. Social Problems, 35(4), 418–441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/800595

- Jefferson, G. (1984). On the organization of laughter in talk about troubles. In J. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 346–369). Cambridge University Press.

- Jefferson, G., & Lee, J. (1980). End-of-grant report on conversations in which “troubles” or “anxieties” are expressed (HR 4805/2). Social Science Research Council.

- Kupetz, M. (2014). Empathy displays as interactional achievements—Multimodal and sequential aspects. Journal of Pragmatics, 61, 4–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.11.006

- Kuroshima, S., & Iwata, N. (2016). On displaying empathy: Dilemma, category, and experience. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(2), 92–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1164395

- Local, J., & Walker, G. (2005). Methodological imperatives for investigating the phonetic organization and phonological structures of spontaneous speech. Phonetica, 62(2–4), 120–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000090093

- Mandelbaum, J. (1991). Conversational non‐cooperation: An exploration of disattended complaints. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 25(1–4), 97–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08351819109389359

- Mondada, L. (2016). Conventions for multimodal transcription. Romanisches Seminar der Universität. https://franz.unibas.ch/fileadmin/franz/user_upload/redaktion/Mondada_conv_multimodality.pdf

- Niemelä, M. (2011). Resonance in storytelling: Verbal, prosodic and embodied practices of stance taking [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Oulu. http://jultika.oulu.fi/files/isbn9789514294174.pdf

- Ogden, R. (2010). Prosodic constructions in making complaints. In D. Barth-Weingarten, E. Reber, & M. Selting (Eds.), Prosody in interaction (pp. 81–104). John Benjamins Publishing.

- Pomerantz, A. (1986). Extreme case formulations: A way of legitimizing claims. Human Studies, 9(2/3), 219–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00148128

- Pudlinski, C. (2005). Doing empathy and sympathy: Caring responses to troubles tellings on a peer support line. Discourse Studies, 7(3), 267–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605052177

- Raymond, G., & Heritage, J. (2006). The epistemics of social relations: Owning grandchildren. Language In Society, 35(5), 677–705. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404506060325

- Ren-Mitchell, A. (2018, January 19). Gesture coding manual. http://adainspired.mit.edu/gesture-research/gesture-coding-manual/

- Rossi, G. (2011). The MPI/Rossi corpus of English [ Data set]. The Max Planck Institute.

- Ruusuvuori, J. (2005). “Empathy” and “sympathy” in action: Attending to patients’ troubles in finnish homeopathic and general practice consultations. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(3), 204–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800302

- Ruusuvuori, J., Asmuß, B., Henttonen, P., & Ravaja, N. (2019). Complaining about others at work. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 52(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1572379

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E., & Jefferson, G. (1974). The simplest systematics for the organization of turn taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1974.0010

- Schegloff, E. (2005). On complainability. Social Problems, 52(4), 449–476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2005.52.4.449

- Schegloff, E. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: Volume 1: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- Selting, M. (2010). Affectivity in conversational storytelling: An analysis of displays of anger or indignation in complaint stories. Pragmatics, 20(2), 229–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.20.2.06sel

- Selting, M. (2012). Complaint stories and subsequent complaint stories with affect displays. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(4), 387–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.01.005

- Selting, M., Auer, P., Barth-Weingarten, D., Bergmann, J., Bergmann, P., Birkner, K., Couper-Kuhlen, E., Deppermann, A., Gilles, P., Günthner, S., Hartung, M., Kern, F., Mertzlufft, C., Meyer, C., Morek, M., Oberzaucher, F., Peters, J., Quasthoff, U., Schütte, W., Stukenbrock, A., & Uhmann, S. (2011). A system for transcribing talk-in-interaction: GAT 2 translated and adapted for English by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Dagmar Barth-Weingarten. Gesprächsforschung–Online-Zeitschrift Zur Verbalen Interaktion, 12, 1–51. http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2011/px-gat2-englisch.pdf

- Sidnell, J. (2012). Turn-continuation by self and by other. Discourse Processes, 49(3–4), 314–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2012.654760

- Traverso, V. (2009). The dilemmas of third-party complaints in conversation between friends. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(12), 2385–2399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.047

- Walker, G. (2004). The phonetic design of turn endings, beginnings and continuations in conversation [Doctoral dissertation]. University of York. http://gareth-walker.staff.shef.ac.uk/pubs/2004-Walker-phd.pdf