ABSTRACT

This article uses multimodal CA to analyze depictive hand gestures that are used to check understanding of the co-participant’s preceding action. Drawing on data from cooking and farming interactions, the analysis scrutinizes how depictive gestures come to be treated as other-initiations of repair. The analysis shows that relevant factors in this are: (a) the gesture’s design, i.e., its form and movement in relation to the material ecology of the interaction, including relevant objects; (b) the gesture’s position and timing in the unfolding sequence; (c) the embodied participation framework, including the body positions and gaze patterns of all participants; and (d) the participants’ shared knowledge and understanding of the broader activity context, including their familiarity with the ingredients and dishes in-the-making. The analysis contributes to research on gestural depiction in human meaning making and to the study of embodiment in repair organization. The data are in Finnish with English translations.

This article analyzes hand gestures that depict manual actions (see Clark, Citation2016; Streeck, Citation2009), and shows how such gestures are used to check understanding of the co-participant’s preceding action. The gestures we focus on are not accompanied by speech and do not have verbalized lexical affiliates (Schegloff, Citation1984). However, they are treated as recognizable and acceptable social actions in their contexts of use. We scrutinize the factors that are at play in situations where the gestures are treated as social actions on their own and demonstrate that these gestures achieve their meaning and status as social actions in connection to: (a) their design, i.e., the form and movement of the gesture in relation to the material resources in the situation; (b) their specific position and timing in the ongoing sequence; (c) the embodied participation framework (Goodwin, Citation2000), including the body positions and gaze patterns of all participants; and (d) the participants’ shared knowledge and understanding of the broader activity context. The data (52 hours) for our analysis come from farming and cooking interactions in Finnish that were organized for newcomers to Finland. The focal gestures (n = 21) are produced following instructions on how to proceed with a manual task.

Our analysis draws on and contributes to research on depiction in human meaning making (Clark, Citation2016; Streeck, Citation2009). Hand gestures in interaction have been studied in relation to co-occurring speech (e.g., Kendon, Citation2004; Kita, Citation2000; McNeill, Citation1992; Schegloff, Citation1984; Streeck, Citation2009). However, gestures that are produced in the absence of accompanying speech have received less attention (see Hsu et al., Citation2021). We therefore set out to analyze depictive gestures that function as social actions without accompanying speech and aim to bring about new understanding of how the gestures are recognized and treated as social actions in interaction. The analysis also contributes to previous CA research on repair organization by showing how depictive hand gestures are used to present a specific understanding of the previous turn for confirmation. In this way, the depictive gestures work as candidate understandings, i.e., as one type of restricted other-initiation of repair (Dingemanse et al., Citation2014).

Depictive gestures in interaction

Research on gestures has been guided by two fundamental questions. The first concerns the relationship between gestures and speech. Gestures are usually analyzed in relation to speech and understood to complement and refine meanings communicated through words (Gullberg, Citation1998; Kendon, Citation2004; Kita, Citation2000; McNeill, Citation1992). The second question targets the methods by which hand gestures are used to create meanings (Müller, Citation2014; Streeck, Citation2009). To understand gestures’ relationship to speech and the ways they make meanings relevant, it has been useful to classify hand gestures into different types (for an overview, see Kendon, Citation2004). In most studies, three main classes are identified: (a) deictic gestures that are used to locate something in space and time by pointing; (b) pragmatic gestures that highlight or punctuate some part of talk or serve a discourse-structuring function, such as open palm hand shapes that offer the turn to the next speaker; and (c) depictive (iconic, representative, expressive) gestures that show what something “looks or sounds or feels like” (Clark, Citation2016, p. 342) by hand shapes and movement.

The different methods of gestural depiction have been analyzed in detail by Streeck (Citation2009) and Müller (Citation2014). Streeck (Citation2009) identifies three modes of gestural depiction: drawing, i.e., moving hands in the air in a similar way as drawing with pen on paper, handling, i.e., gestures designed to depict actions done with objects or tools, and mimesis, i.e., showing physical acts or behaviors by gesturing. Müller (Citation2014), in turn, talks about acting, in which hands mime actual manual activities, such as grasping or holding, and representing, where the hands become other entities. The gestures we analyze in this article depict by handling (in Streeck’s terms) and by acting (in Müller’s terms). Importantly, such gestures are shaped by our “body’s practical acquaintance with a tangible environment” (Streeck, Citation2009, p. 150) and draw on our embodied understanding of the scenes we depict (Clark, Citation2016).

In his theory of depiction as a “basic method of communication,” Clark (Citation2016) differentiates four types of depictions based on how they are related to speech: (a) adjunct gestural depictions that accompany their verbal affiliates (see also, Schegloff, Citation1984); (b) indexed depictions in which the gestural (or other type of) depiction is indexed in speech, e.g., with a deictic pronoun or demonstrative; (c) embedded depictions in which the depiction occupies a syntactic slot in a structure (see also Keevallik, Citation2013 on syntactic-bodily units and Mori & Hayashi, Citation2006; Olsher, Citation2004 on embodied completions); and (d) independent depictions that are not accompanied by speech. Embedded and independent depictions have thus far received less attention in research (see Hsu et al., Citation2021). The depictive gestures we analyze in this article are independent depictions. Nonetheless, they are treated as recognizable social actions in their context of use. It is important to note, however, that even though such independent depictions are not accompanied by speech, they are still framed by the sequential environment provided by talk and understood in relation to the activity context, material environment, and objects relevant in the situation (Goodwin, Citation2007).

Gestural resources in other-initiated repair

The conversation analytic research on repair phenomena evidences the systematic organization of practices available for participants to restore intersubjectivity should they confront trouble in speaking, hearing, or understanding (see, e.g., Dingemanse et al., Citation2014; Kendrick, Citation2015a; Schegloff et al., Citation1977). Repair initiation is distinguished from repair solution. Self is the party whose actions are treated as the source of trouble, and other is the recipient of the treated-as-troublesome-talk. In other-initiated repair sequences, the recipient indicates the presence of trouble by launching an other-initiation of repair (henceforth OIR).

Research on repair organization has demonstrated that verbal OIRs are formatted differently according to how precisely they locate the trouble source. While open type repair initiators merely indicate the presence of trouble, restricted types identify a specific part of the previous turn as the trouble source (Dingemanse et al., Citation2014). Candidate understandings have been described as the most specific type of restricted OIRs, as they present a possible understanding of the trouble-source turn for confirmation (see e.g., Kurhila, Citation2006; Schegloff et al., Citation1977). In Finnish interaction, candidate understandings (henceforth CUs) are typically designed as declarative clauses or as noun phrases with particles indicating inference (Haakana et al., Citation2016). The depictive gestures analyzed in this article are treated by their recipients as presenting an understanding of the preceding action for confirmation or correction. In this sense, they are comparable to verbal CUs.

Research on embodiment in repair contexts has shown how especially upper body movements (head, face, hands, and torso) are relevant for repair. Seo and Koshik (Citation2010) analyze head pokes and tilts used to initiate repair, Mortensen (Citation2016) demonstrates how the gesture of “cupping the hand behind the ear” is treated as an OIR in classroom interaction, and Oloff (Citation2018) shows how lifted eyebrows combined with head movements or freezes work as OIRs in L2 and lingua franca interaction. These studies indicate that embodied OIRs work similarly to verbal OIRs: They are produced in turn transition spaces projecting repair as the next relevant action. All the analyzed embodied actions have been shown to function like open type repair initiators. Kendrick (Citation2015b) has shown that repair-relevant embodied actions, such as gaze shifts or raised eyebrows, are produced early in turn transition spaces, either before the end of the trouble-source turn or immediately after it. Sometimes such embodied actions also occasion self-repair and work as OIRs independently (Kendrick, Citation2015b; Oloff, Citation2018).

The continued need for repair can also be signaled by embodied means. Floyd et al. (Citation2016, p. 9) have shown how holds, i.e., “any meaningful maintenance of stationary bodily configuration,” are used to display orientation to the not-yet-resolved status of the repair sequence. Holds are ensembles of different embodied resources, such as manual gestures, body postures, movements, and gaze. A hold usually begins as the repair is initiated and is held until the onset of the repair solution (Floyd et al., Citation2016). A similar practice is analyzed by Kamunen (Citation2019), who shows how repair-initiating speakers temporarily disengage from the ongoing manual activity and twist their upper body toward their co-participants to focus on a repair sequence and display increased involvement in the attempts to solve the interactional trouble. Our analysis contributes to the research on embodied actions for repair organization and provides new understanding of how depictive gestures are used to present a candidate understanding of preceding action for confirmation.

Data and method

The data for this study consist of video-recorded interactions within an NGO-led urban farming project for immigrants in Finland. The interactions took place in various settings connected to farming: learning about cultivation in classrooms, cultivating patches of land, and utilizing the agricultural products in cooking. The overall goal of the project was to promote newcomers’ integration into Finnish society by learning how to grow vegetables in Finnish climate conditions and prepare Finnish dishes. Learning the language was not the main objective of the activities (cf. Kurhila & Kotilainen, Citation2020; Preston et al., Citation2015), but since Finnish was the language shared by all the participants and used throughout the activities, the interactions also provided opportunities for language learning (see Jokipohja, Citation2022).

The data consist of 43 recordings of separate events, 52 hours in total (21 hours of cooking and 31 hours of farming) spanning over 19 months. The data were collected with the informed consent of the participants. There are altogether 20 regular participants in the data set: 13 beginning L2 users of Finnish, their L1 being predominantly Arabic, and seven cooking and farming instructors or other first-language speakers of Finnish. Pseudonyms are used in the transcripts and analysis, but the participants have given permission to present unedited images.

The whole data set was used in forming the core collection on which this article is based. The collection consists of 17 sequences in which there are 21 depictive gestures that work as candidate understandings without accompanying speech. In the initial phase of the analysis, we compiled a preliminary collection of instances in which the participants’ gestures seemed to carry the main meaning of their action and noticed that gestures were recurrently used as OIRs. We then narrowed the collection to these instances. We decided to leave deictic gestures out of the collection because their logic is different from that of depictive gestures. This article focuses on actions composed of independent depictive gestures (n = 21). Although the collection allows for identifying a recurring practice, it also reveals that independent depictive gestures are not frequently used to initiate repair. Most of the examples in this article come from cooking interactions, since the depictive gestures used as CUs are more frequent in the cooking than farming interactions.

The analysis will show that the use of depictive gestures as candidate understandings is connected to the sequential and activity context of the interaction and to the participants’ familiarity with the ingredients, dishes in-the-making, and the language of the interaction. Our methodological practices have been guided by the conversation analytical principle of not presupposing the relevance (or irrelevance) of any speaker category in the analysis (Sidnell, Citation2013). In some studies on second-language interaction, gestural resources have been analyzed primarily as compensation strategies for linguistic deficiencies (see, e.g., Gullberg, Citation1998). In this study, we adopt an emic perspective to understand whether different asymmetries are relevant and how they become observable in the details of interaction.

The data have been transcribed following the conventions for multimodal transcription developed by Mondada (Citation2018, Citationn.d.). We present the sequences in the analysis also as graphic transcriptions to illustrate the unfolding of gestural actions (see Laurier, Citation2014; Skedsmo, Citation2021). The graphic transcripts do not represent the temporal unfolding of the sequences in as much detail as the verbal transcripts; methodologically, however, their advantage is that they highlight the progression of action. We have also indicated the location of each image in the multimodal transcript.

Analysis: Depictive gestures as other-initiations of repair

The following analysis demonstrates how depictive gestures are used to check understanding of the previous action. We present the analysis in three parts. All the extracts illustrate recurrent features of the sequences in which depictive gestures are used as CUs, each highlighting different aspects of the focal sequences in our collection. The first part of the analysis introduces the main characteristics of the sequences in which gestural CUs are used (). The second part focuses on highlighting the relevance of the embodied participation framework for the understanding of gestures as social actions on their own (). The third part () illustrates the role of material ecology for action ascription and demonstrates how carefully the participants observe the gestures and interpret them in relation to the tools and ingredients relevant to the situation (see, e.g., Mondada, Citation2014b).

The recurrent features of focal sequences

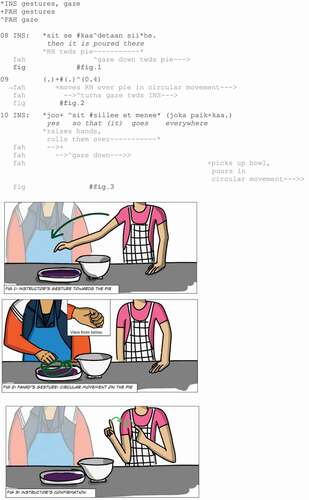

The first two extracts illustrate the basic sequential features of the cases in the collection. comes from a cooking situation where the participants are baking a blueberry pie. The focal gesture is used to check understanding of the correct way of pouring cream topping. comes from a farming situation where some organic fertilizer (chicken manure) needs to be mixed into soil. Here, the focal gesture is used to check understanding of the mixing action.

In , the instructor instructs Fahad to pour cream topping onto the pie (line 8). The instruction is designed as a multimodal gestalt composed of verbal, gestural, and material resources (Mondada, Citation2014b). Linguistically, it is recognizable as a complete turn both syntactically and prosodically: It consists of the passive declarative form of the verb “to pour” (kaadetaan), the object of the pouring action in sentence-initial position (se, “it”) and the location (siihe(n), “there”) indexed with demonstrative pronouns. The linguistic component is accompanied by the instructor’s right-hand movement toward the pie, marking the pie as the focus of attention (). The instructor and Fahad stand next to each other and gaze toward the pie (line 8). In this way, they form a shared embodied participation framework, i.e., they display visual and cognitive attention toward each other, the gesture, and the structure in the physical surroundings that is made relevant by the instructor’s gesture (Goodwin, Citation2000, Citation2007; Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation2004).

Extract 1. Pouring the cream topping

The focal depictive gesture is performed by Fahad and initiated a micropause after the instruction (line 9, ). Fahad’s right hand is positioned sideways, fingers bent toward the palm of the hand, thumb resting on them, in a position that is used to hold an object (i.e., in palm opposition, see Streeck, Citation2009, p. 48). The hand moves in a circle over the pie dish, near the rim (). The gesture is enacted close to the pie, in the position from where the topping will be poured. After initiating the gesture, Fahad directs his gaze toward the instructor, signaling that the gesture is used as a social action inviting reaction from the instructor (line 9).

The instructor treats Fahad’s gesture as seeking confirmation and thus orients to it as a candidate understanding of her preceding instruction. She confirms Fahad’s gestural depiction with joo (“yes”) and by verbalizing that the topping is supposed to be spread evenly on the pie which is also implicated in her co-occurring depictive gesture (line 10, ). This verbalization shows her interpretation of Fahad’s gesture as a request for confirmation for his understanding of pouring the topping evenly on the pie. After the confirmation, Fahad picks up the bowl and starts pouring (line 10).

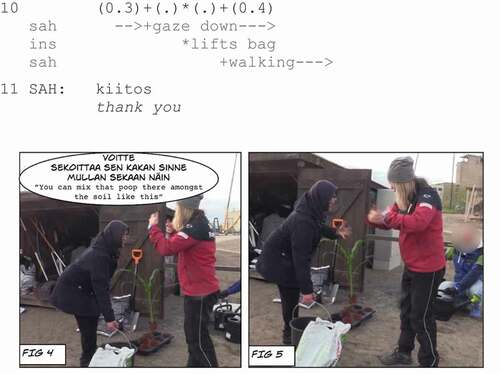

In , the gardening instructor instructs Sahba and her co-farmer (not visible in the images) to mix chicken manure into soil. The instruction is designed as a multimodal gestalt: It is formulated with a modal verb in the second-person plural (voitte, “you can”) combined with the main verb referring to the instructed action (sekoittaa, “to mix”) and naming the relevant substance (sen kakan, “that poop”) (line 6). The instructor also moves both arms in front of her chest in a circular manner, depicting the action of mixing (lines 6–9, ). The gesture is indexed verbally with the adverb näin (“like this”) (line 7). The main verb, sekoittaa, and the stroke of the depictive mixing gesture are delayed until Sahba gazes at the instructor, and they share a mutual orientation to each other (line 6).

Extract 2. Mixing the chicken manure

The focal depictive gesture is performed by Sahba (line 7, ). She starts preparing for the gesture while the instruction is still unfolding, and the stroke overlaps with the last word of the instruction. Sahba’s gesture is a left-hand circular movement in the air. She thus recycles the instructor’s gesture movement. Sahba’s gesture becomes understandable as depicting mixing and checking understanding in relation to the previous instructive action and the materials (manure, soil) relevant to the situation. Sahba is looking at the instructor while gesturing, thus inviting a response. The instructor responds with a minimal confirmation (line 9), which indicates that she treats the gesture as a CU. After the confirmation, Sahba starts walking to the greenhouse (line 10), where she then mixes the manure into the soil.

demonstrate the basic features of the sequences in our data set, where depictive hand gestures are used as candidate understandings seeking confirmation. The recurrent features are the following:

Virtually all the trouble-source turns in the collection are multimodal gestalts (Mondada, Citation2014b) composed of verbal, gestural, and material resources feeding into the action formation and ascription (Levinson, Citation2013) of the instruction. The instructions recurrently involve depictive gestures and project a complying manual action as the relevant next (see also, Mondada, Citation2014a). Linguistically, the instructions are designed with modal verbs, making them sound like suggestions (see ). In addition, the instructions overwhelmingly use forms that do not include person marking (such as the passive in , and zero-person construction in ).

The gestures are oriented to as candidate understandings of the previous instruction by their recipient. They are composed of gesture form and movement, which both contribute to action ascription. The gestural depictions are closely connected to their environment and the relevant materials (Goodwin, Citation2007): The assembling of the fingers often depicts holding an object that is relevant for the realization of the instructed action, and the hand is moving close to the objects that are relevant to the depicted action. The depictive gestures also recycle gestural elements from the preceding instruction.

The gestural CUs (n = 21) are performed early in transition spaces. The gesture strokes appear in slight overlapFootnote1 with the trouble-source turn (n = 5), following the trouble-source turn immediately (n = 7), after a micropauseFootnote2 (n = 6), or after a slightly longer pause, but no more than 0.8 seconds (n = 3). The slightly longer pauses appear in situations where the gesture presents a meaning not intended by the instructor, i.e., a “wrong” understanding in the instructor’s view (see ). The gesture preparations and strokes were identified in relation to the rest position: During the preparation, the hand(s) move away from their current position. The preparation leads to a stroke characterized by hand shapes and movements that are “better defined” compared to the surrounding hand motions and figures (see Kendon, Citation2004, pp. 111–112).

The gestural CUs are typically followed by the instructor’s confirmation (n = 18). The instructed action takes place after the instructor has confirmed the gestural candidate understanding. In three cases, the CUs are corrected (see ).

The participants orient their bodies and gaze toward each other, thus forming a shared embodied participation framework. They also gaze toward their gesturing hands.

The importance of the shared embodied participation framework

Gestures can implement social actions only if participants see them and orient to them as relevant. Extra work is sometimes needed to draw the recipient’s attention to the gesture. demonstrates the importance of the shared embodied participation framework (Goodwin, Citation2000) for the recognition of gestures as social actions.

In the extract, Fahad is preparing leavened bread. The instruction is located at an activity juncture and signals that Fahad is now allowed to proceed to the next phase of the ongoing task, namely, to spread some oil on the bread. The instruction (lines 10–11) is verbally designed as a zero-person construction with a modal verb in the third-person singular (voi pistää, “(0) can put”). The main verb pistää (“to put”) does not specify the way the oil should be added on the bread. The gestural component of the instruction is a right-hand sideways movement on chest level, palm facing downwards ().

The focal gestural CUs are performed by Fahad in lines 11–13, 14–16, and a CU with a verbal component in lines 18–20.

Extract 3. Brushing the bread with oilFootnote3

In this sequence, Fahad attempts three times to check his understanding of how to apply the oil. These attempts are not successful because the participants do not achieve an embodied participation framework that allows mutual visual access to the focal gesture. The instructor does not observably orient to the first gestures: The first time she is turning away to leave (line 11), and the second time, she looks down (line 16).

In the focal gesture, Fahad recycles the horizontal movement that was visible in the instructor’s gesture. However, he does the movement with his wrist, hand dangling downwards, and switches the direction of the movement into back and forth. His fingers are organized differently compared to the instructor’s: The thumb, forefinger, and middle finger are pinched together (lines 11–13, 14–16, ) in a way that looks like grasping a rather small and lightweight object (i.e., side opposition, see Streeck, Citation2009, p. 48). The gesture is done close to the bread. Based on the design, the gesture seems to depict and specify at least two aspects that the instructor will later address in her response: How the oil should be “put” on the bread (hand movement) and whether a tool is needed in the process (finger position). Thus, Fahad offers for confirmation his proactive understanding of how the instructed action should be performed (cf. Kurhila, Citation2006, pp. 188–194).

Importantly, Fahad adjusts the embodied participation framework by a recurrent gaze pattern in all three uses of gesture (see Goodwin, Citation2007; Streeck, Citation2009): He first gazes toward the instructor (lines 10, 14, 15), then glances at his hands around the onset of the gesture (lines 11, 14, 16), and lastly, looks back at the instructor (lines 11, 15, 18). In this way, Fahad monitors his interlocutor’s focus of attention and points to his hands as relevant for the ongoing action. These independent gestural CUs are timed to occur early: Their preparations are done simultaneously with the last syllables of the instructions, and the gesture strokes occur immediately in transition spaces after the instructions (lines 11, 14). However, Fahad does not manage to solicit the instructor’s attention during the first two attempts, relying only on visual resources. Consequently, Fahad’s next turn (lines 18–20, ) consists of verbal and gestural resources. The audible component mitä (“what”) serves to attract the instructor’s attention and indicate the presence of trouble (Drew, Citation1997). The gestural component is a similar movement of the downward open palm. Together the gesture and the word mitä (“what”) seek confirmation for his understanding of how to apply the oil. This time the gesture stroke is maintained until the instructor starts formulating her response, thus accentuating the response’s relevance and solving the interactional trouble (see Floyd et al., Citation2016).

The instructor attends to Fahad’s gesture only after the third attempt. She confirms Fahad’s gestural CU by an affirmative particle joo and a very subtle mirroring brushing gesture (line 20). Then she verbalizes the need of a brush and leaves to find one (line 20). The repair solution appears in lines 22–23 in an upgraded format (Hauser, Citation2019): After Fahad has expressed trouble in understanding, the instructor modifies her original gestural instruction into a more distinct depiction. This specification is sequentially prompted by the features visible in Fahad’s gesture: The instructor incorporates the utensil to be used, holds it with a pinch, and moves the brush back and forth on the bread, recycling the hand position and direction from Fahad’s gestural candidate understanding (). Also, the verb pistää (“to put”) is replaced with the more precise verb sutia (“to brush”), and the oil bottle is indexed with touch (lines 23, 26).

illustrates that for gestures to be treated as social actions, they have to be timed carefully and seen by the recipients. The extract also elucidates the gaze pattern of looking at one’s hands when starting to gesture and then orienting the gaze back to the interlocutor. In this extract, the independent gestural CUs are timed to occur early in transition spaces, the preparation phase occurring simultaneously with the last word of the previous turn. The instructor’s attention, however, is not properly secured, and therefore the gestural actions are not acknowledged as CUs during the first two attempts. The extract also illustrates how detailed the depictive gestures’ design is. The depiction in the candidate understandings is done with a specialized hand shape: The assembling of the fingers contributes to the meaning and reveals the participants’ embodied knowledge of the cooking action. The depiction also gets its precise meaning from the proximity of the material resources tied to the actual cooking task.

The role of tools and ingredients for action ascription

The gestural candidate understandings in our data set are typically confirmed. In other words, the understanding that they present for confirmation is accepted as the correct understanding by the instructor. However, there are three cases in our collection in which the understanding presented by the gestural CU is corrected. Such sequences illustrate how carefully the participants attend to the gestures (see also Arnold, Citation2012). In addition, they exemplify how the gestures are connected to the participants’ embodied knowledge and evolving understanding of the ongoing cooking procedure.

illustrates a situation in which the instructor treats the gestural candidate understanding as presenting a partially incorrect understanding of the instructed task. Fahad is instructed to sprinkle breadcrumbs on a beetroot casserole. During the sequence, he produces several candidate understandings. The focal gesture is in lines 10–12, and other CUs with co-speech gestures in lines 13–14, 18, 26–27.

Extract 4. Sprinkling breadcrumbsFootnote4

The instruction in is a multimodal gestalt composed of verbal and gestural resources and the use of gaze as a pointer. The instructor first places a spoon on the table then presents the bag of breadcrumbs, naming it (koppujauhoja, “breadcrumbs”) in sentence-initial position (lines 5, 9). She then refers to the action using a passive verb form ripotellaan (“are sprinkled”) and indicates the location with a demonstrative pronoun combined with a noun in the allative case, siihen pinnalle (“there onto the surface”). The verbal component is accompanied by a depictive gesture that is initiated prior to the verb and indexed with gaze (lines 9–10, ). The gesture is a linear, right-hand movement over the casserole with the fingers straightened downward and a wiggling movement of the wrist. The gesture has visual similarity to the action of sprinkling. The gesture trajectory is adapted to the physical features of the environment (see Goodwin, Citation2007) and done precisely over the casserole. The instructor monitors Fahad’s gaze orientation, looking at him at the beginning and end of her turn, making sure they share an embodied participation framework.

Fahad initiates a depictive gesture simultaneously with the last syllable of the instruction (lines 10–12). The gesture stroke is a circular movement, and the fingers are organized differently compared to the instructor’s gesture: The thumb, forefinger, and middle finger are extended downward with a small space in between (). Fahad’s assembling of fingers does not clearly depict sprinkling; rather, the stationary fingers and the circular movement resemble a stirring action. At the onset of the gesture, Fahad looks at his hands (line 9), then toward the instructor, who has glanced at his hands, and mutual gaze is established at the end of Fahad’s gesture (line 11, ). In this way, the participants adjust the embodied participation framework to assess whether each has seen the gesture in its material environment.

The instructor treats Fahad’s gestural CU as presenting a partially incorrect understanding of the sprinkling action, namely, of the amount of the breadcrumbs: She shakes her head and says ei paljoo (“not much,” line 12). Next, she specifies that there should only be “a very thin layer” (hyvin ohut kerros, line 12) of breadcrumbs sprinkled on the casserole. She depicts the layer with a horizontal movement of the thumb and forefinger positioned close to each other (). This response evidences that the instructor has interpreted Fahad’s gesture for a precise meaning.

Following this correction, Fahad grasps the casserole with both hands (line 15) and verbalizes his understanding that there should be only a small amount of breadcrumbs added on top of the casserole (line 18; bäällä, “on top”). This is confirmed by the instructor (line 20).

Despite the instructor’s specifications, Fahad does not proceed into sprinkling. Instead, he solicits the instructor to check his understanding once more and expresses the need for a specific measurement (lines 24–27, ). This illustrates how understanding intertwines with previous experience of cooking. Notably, Fahad’s understanding is also guided by the nearby material objects. He has looked at the bag of breadcrumbs and the spoon (line 5) and treats the spoon as relevant for the instructed action by picking it up. He shows his understanding of using the spoon by incorporating it into the gesture-speech CU (lines 26–27, ). The instructor responds to Fahad’s CU with an explicit demonstration of sprinkling the breadcrumbs (lines 29–37, ; see also Stukenbrock, Citation2014). This response showcases the importance of embodied knowledge for understanding cooking instructions, since Fahad claims understanding only after the demonstration. He does this with a firm, emphatic aaha (line 33, Figure 18), indicating that the demonstration has changed his previous understanding and the anticipated course of action (Koivisto, Citation2017).

Example 4 sheds light on how the material environment and previous knowledge of cooking activities shape understanding of instructions and are reflected in the gestural CUs. The trouble in understanding is related to the unfamiliarity of the word “to sprinkle” but even more to the embodied understanding of performing a sprinkling action. The hand shapes and movements by the instructees reveal understanding or nonunderstanding of the instruction, and these features are attended to for a precise meaning by the instructor (see also Arnold, Citation2012).

Next, we move on to a deviant case which makes visible, through a breakdown of mutual understanding, the importance of sequential, material, and activity contexts for the understanding of depictive gestures as CUs. is the only sequence in our collection where the instructee (Rami) offers for confirmation an understanding that is completely different from what the instructor has meant. In the extract, Rami and the instructor are not on the same sequential track: The instructor’s turn is a suggestion for tasting, but Rami treats it as an instruction for the next cooking action (stirring the soup), which is displayed in his depictive gesture seeking for confirmation. The incongruity of the participants’ actions creates a situation in which the participants have trouble in ascribing the right actions to each other’s turns.

The instruction is a suggestion to taste the cold tomato soup and assess whether some spices should be added (lines 1–2, ). As the instructor articulates the verbal component of the instruction, she moves her right hand, holding a spoon, toward Rami (line 2). She also produces a vague swinging movement with the spoon. The focal gestures show how Rami has trouble in ascribing an action to the instructor’s turn (lines 3, 5, 12, 19; see also Levinson, Citation2013).

Extract 5, tasting the soupFootnote5Footnote6

Rami has glanced at the spoon during the first part of the instruction (line 1). A micropause after the instruction, Rami launches a gesture that recycles the instructor’s right-hand circular movement and finger position of holding a lightweight object (line 3, ; side opposition; see also ). During Rami’s gesture the instructor reformulates the verbal turn into an interrogative haluatko maistaa (“do you want to taste”), prompting tasting (line 4). At this point, Rami looks at the instructor, takes the spoon, and produces an upgraded repeat (Hauser, Citation2019) of the circular gesture—this time with the spoon over the soup container (lines 4–6, ). By incorporating the spoon into the gesture and performing it over the soup, the depiction is made more explicit. It seems that Rami relies on the cooking context and the spoon to infer the meaning of the instructor’s turn: In this context, spoons are regularly used for stirring. After the gesture, Rami gazes toward the instructor and adds a nonstandard verbal component teken (line 6), which might be a combination of the third-person singular form tekee of the verb tehdä (“to do/to make”) and the first-person suffix -n.

The upgraded gestural repetition together with gaze and a verbal addition pursue a response from the instructor. The instructor provides a minimal confirmation (line 8), but Rami treats it as insufficient. He verbalizes the presence of trouble with an open type repair initiator mitä (“what”) and turns the spoon in his hand, indexing trouble in understanding what he is supposed to do with the spoon (line 9). The instructor leans forward and reacts with the same open type repair initiator, indicating trouble in hearing or general attentiveness (line 11). Rami indexes the suspended spoon with a prolonged gaze, repeats the circular movement over the soup, and shakes his head (line 12, ). The suspension together with the head shake and slightly puzzled facial expression signal continued trouble in understanding (Floyd et al., Citation2016). The instructor produces a similar gesture and says kauha (“a ladle”), thus orienting to the object and not the action (lines 13–15, ). Eventually, Rami shakes his head repeatedly while verbalizing his nonunderstanding and allocating the problem to the instructor’s speech (lines 15–16).

The instructor responds with a turn in which she foregrounds the verb maistetaan (“let’s taste”) to sentence-initial position (line 18). This makes the turn a more explicit instruction, indicating that both the instructor and Rami are to taste the soup. She also moves the spoon closer to the soup and then back close to herself, which bears a visual resemblance to tasting (). However, the gesture is not produced as a defined action to look at: There is no indexing gaze pattern, and the depiction is not completed with bringing the spoon close to the mouth.

When the instructor and Rami share mutual gaze, Rami produces a more complete depiction of tasting by bringing his spoon close to his mouth and mimicking the tasting action simultaneously with the instructor’s further explanations (line 19, ). This time the instructor confirms Rami’s gestural candidate understanding immediately (line 19)—she interrupts her ongoing turn and prioritizes solving the interactional trouble. Rami signals delayed understanding by the discourse particle aa, indicating grasping something that was previously unclear (Heritage, Citation1984; Koivisto, Citation2015). The particle together with Rami’s repetition of maistetaan indicate that he is familiar with the word maistaa. Rami immediately proceeds to tasting (lines 20–21, ).

All in all, this extract supports our analysis of the relevance of the sequential position for understanding the depictive gesture and the action implemented by it. Here, Rami’s gesture is unexpected for the instructor because it introduces an action that was not projected by her prior turn. This shows in the instructor having trouble understanding Rami’s gestural CUs. What follows is a long repair sequence in which the trouble in understanding is gradually resolved.

Summary and discussion

In this article, we have analyzed depictive gestures that are used to present a candidate understanding of the preceding action for confirmation. The analysis has shown that depictive gestures acquire their meaning and function as other-initiations of repair in a complex way. The relevant factors in this are: (a) the gesture’s design, i.e., the form and movement of the gesture in relation to the material resources and objects in the situation; (b) the gesture’s specific position and timing in the ongoing sequence; (c) the embodied participation framework, including participants’ body positions and gaze patterns; and (d) the participants’ shared (or not shared), partly embodied knowledge and understanding of the broader activity context, including their familiarity with the ingredients and dishes-in-the-making. In the following, we summarize the findings connected to these factors.

Our analysis has shown how the techniques of depicting are both independent and context-dependent. The gestures are independently recognizable in that they draw on shapes of hands, assemblance of fingers, and hand movements that are recognizable as referring to the depicted actions in themselves. However, the gestures get their specific meaning in relation to the material environment and the sequential context of the preceding turn with its verbal and gestural features. The tools and ingredients made relevant in the situation guide the understanding of the gestures connected to them and in some sense can also be understood to work as instructions on their own (Garfinkel, Citation2002).

The focal depictive gestures recycle elements from the preceding instruction () or develop and modify the gestural elements to offer a more elaborate candidate understanding of the instructed action (). The gestures are performed close to the items relevant to the instructed action, and the gesture trajectory is often adjusted to the shapes in the environment (e.g., over the dish and following the edges of the container, ). This helps to make the gestural depictions more precise in the context. For example, a left-to-right movement can be transformed into a back-and-forth movement that is more suited to the shape of the bread-in-the-making, and an open palm can be reformed into a finger position used to hold a lightweight object ().

It is worth noting that the investigated depictive gestures exhibit features that are typically associated with pointing gestures: Their understanding is intrinsically intertwined with the material resources in the physical environment, meaning that they are environmentally coupled with the situationally relevant tools and ingredients (Goodwin, Citation2007). In previous research, gestural depiction has not been widely studied in relation to the material ecology of analyzed interactions. Our analysis underlines the importance of studying depictive gestures in relation to their material environment. The analysis provides evidence that even though gestures might be understandable to some extent through their design, the environment and activity context offer an important grounding point for (gestural) meaning making when doing practical actions.

The sequential position of the depictive gestures without co-occurring speech is central in guiding action ascription: The focal gestures in our collection are performed in a position where complying second action is expected and thus produced instead of that action (see also Mondada, Citation2014a). Because of this, these gestures are easily recognizable as actions seeking confirmation.

The analysis demonstrated that the depictive gestures used as candidate understandings are carefully timed to occur early in transition spaces following the trouble-source turn. The preparation (, ) and sometimes the gesture stroke () occur simultaneously with the preceding verbal turn or a micropause after (, ), supporting previous research showing that embodied OIRs are initiated swiftly (Kamunen, Citation2019; Kendrick, Citation2015b; Oloff, Citation2018; Seo & Koshik, Citation2010). This provides further evidence that embodied OIR formats differ from their verbal counterparts, which typically occur after noticeable gaps (Kendrick, Citation2015b; Schegloff et al., Citation1977). In our collection, longer gaps (max. 0.8 seconds) are rare and found only in situations where the manual instructed action is observably unexpected for the instructee (). However, since seeing the gesture is necessary for understanding the action it implements, gestural CUs might be delayed from the immediate position after the trouble-source turn because of lack of mutual gaze ().

Our analysis has illustrated the importance of mutual visual access to the gesture and the coparticipant for understanding independent gestures as social actions. The participants monitor each other’s gaze orientation and position their gestures to moments of mutual gaze (, ), in this way securing the embodied participation framework (Goodwin, Citation2000, Citation2007; Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation2004). The depictive gestures are indexed as relevant for the ongoing interaction with a recurrent gaze pattern of switching gaze from the coparticipant to one’s own gesturing hands around the onset of the gesture and then back to the coparticipant to invite a response (especially , ; see also Streeck, Citation2009).

In addition, the activity context of farming and cooking makes relevant the epistemic positions of the participants. The instructions and depictive gestures are embedded in a context where certain manual actions are expected and understandable, depending on whether the participants have previous knowledge and embodied understanding of the manual tasks, ingredients, and dishes. Our analysis illustrated how the activity context, objects, and understanding of their uses guide understanding, and how the possible trouble is related to asymmetry in knowledge about the ongoing cooking procedures (, ). For example, an instruction is not understood when the instructed action is unexpected in the local context, and thus the instructee ends up suggesting another action that would be more commonly done with the tool relevant in the instruction (). Sometimes the participants also offer for confirmation understandings involving meanings that are not made explicit in the instructions: The depictive gesture might orient to the use of a tool () or specify the location where the cream topping should be poured (). This shows that the participants draw conclusions of the instructions also based on their previous knowledge and experience of cooking.

Altogether, the collection analyzed here illustrates that depictive gestures function as an accurate, quick-to-understand resource that responds to the contingencies of the practical activity context. We have shown how depictive gestures can be used independently to present restricted OIRs. This result complements previous research on other-initiations of repair analyzing embodied practices that are used as open type repair initiators (Mortensen, Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Seo & Koshik, Citation2010). Based on our analysis, we suggest that the depictive gestures acquire their specific meaning in connection to their material ecology and exact sequential positioning. It may also be that materially complex environments motivate gesturing when the material resources are used to achieve complex actions. This idea is in line with the observation that in our data set, the gestural CUs are more frequent in the kitchen environment than in the farming interactions (on gesture-speech turns in the kitchen, see also Mondada, Citation2014a; Stukenbrock, Citation2014). It also resonates with the analyses by Olsher (Citation2004, p. 242), who notes that material dimensions can foster opportunities for using partially gestural utterances. These observations and the fact that depictive gestures as other-initiations of repair have not been systematically analyzed before suggest that different contexts may afford and make relevant different ways of initiating and carrying out repair. Consequently, even though repair phenomena are widely studied in CA research, there is a need for deeper understanding of the organization of repair practices in various material contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (125 MB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 That is, overlapping with the last word at the maximum.

2 That is, a pause of 0.2 seconds at the maximum.

3 GIFS illustrating parts of this episode is available on the publisher’s website page for this article.

4 GIFs illustrating parts of this episode are available on the publisher’s website page for this article.

5 A GIF illustrating parts of this episode are available on the publisher’s website page for this article.

6 The beginning of line 1 is not analyzable because the video recording begins from here.

References

- Arnold, L. (2012). Dialogic embodied action: Using gesture to organize sequence and participation in instructional interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(3), 269–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.699256

- Clark, H. H. (2016). Depicting as a method of communication. Psychological Review, 123(3), 324–347. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/rev0000026

- Dingemanse, M., Blythe, J., & Dirksmeyer, S. T. (2014). Formats for other-initiation of repair across languages: An exercise in pragmatic typology. Studies in Language, 38(1), 5–43. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.38.1.01din

- Drew, P. (1997). “Open” class repair initiators in response to sequential sources of troubles in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 28(1), 69–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(97)89759-7

- Floyd, S., Manrique, E., Rossi, G., & Torreira, F. (2016). Timing of visual bodily behavior in repair sequences: Evidence from three languages. Discourse Processes, 53(3), 175–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.992680

- Garfinkel, H. (2002). Instructions and instructed actions. In H. Garfinkel (Ed.), Ethnomethodology’s program (pp. 197–218). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(10), 1489–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

- Goodwin, C. (2007). Environmentally coupled gestures. In S. D. Duncan, J. Cassell, & E. T. Levy (Eds.), Gesture and the dynamic dimension of language: Essays in honor of David McNeill (pp. 195–212). John Benjamin.

- Goodwin, C., Goodwin, M. H. (2004). Participation, and A. Duranti (Ed.), A companion to linguistic anthropology (pp. 222–244). Blackwell.

- Gullberg, M. (1998). Gesture as a communication strategy in second language discourse: A study of learners of French and Swedish. Lund University Press.

- Haakana, M., Kurhila, S., Lilja, N., & Savijärvi, M. (2016). Kuka, mitä, häh? Korjausaloitteet suomalaisessa arkikeskustelussa. Virittäjä, 120(2), 255–293.

- Hauser, E. (2019). Upgraded self-repeated gestures in Japanese interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 150, 180–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2018.04.004

- Heritage, J. (1984). A change-of-state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 299–345). Cambridge University Press.

- Hsu, H.-C., Brône, G., & Feyaerts, K. (2021). When gesture “takes over”: Speech-embedded nonverbal depictions in multimodal interaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–23. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.552533.

- Jokipohja, A.-K. (2022). Kieltä kokkauksen lomassa. Aloittelevien suomen kielen käyttäjien sanastokysymykset. In N. Lilja, L. Eilola, A.-K. Jokipohja, & T. Tapaninen (Eds.), Aikuiset maahanmuuttajat arjen vuorovaikutustilanteissa: Suomen kielen oppimisen mahdollisuudet ja mahdottomuudet (pp. 61–94). Vastapaino.

- Kamunen, A. (2019). How to disengage: Suspension, body torque, and repair. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 52(4), 406–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1657287

- Keevallik, L. (2013). The interdependence of bodily demonstrations and clausal syntax. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.753710

- Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Cambridge University Press.

- Kendrick, K. (2015a). Other-initiated repair in english. Open Linguistics, 1(1), 164–190. https://doi.org/10.2478/opli-2014-0009

- Kendrick, K. (2015b). The intersection of turn-taking and repair: The timing of other-initiations of repair in conversation. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00250

- Kita, S. (2000). How representational gestures help speaking. In D. McNeill (Ed.), Language and gesture: Window into thought, language, and action (pp. 162–185). Cambridge University Press.

- Koivisto, A. (2015). Displaying now-understanding: The finnish change-of-state token aa. Discourse Processes, 52(2), 111–148. doi:10.1080/0163853X.2014.914357

- Koivisto, A. (2017). Uutta tietoa vai oivallus? Eräiden dialogipartikkeleiden tehtävistä. Virittäjä, 121(4), 473–499. https://doi.org/10.23982/vir.59297

- Kurhila, S. (2006). Second language interaction. John Benjamin.

- Kurhila, S., & Kotilainen, L. (2020). Student-initiated language learning sequences in a real-world digital environment. Linguistics and Education, 56, 100807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2020.100807. Article 100807.

- Laurier, E. (2014). The graphic transcript: Poaching comic book grammar for inscribing the visual, spatial and temporal aspects of action. Geography Compass, 8(4), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12123

- Levinson, S. C. (2013). Action formation and ascription. In T. Stivers & J. Sidnell (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 103–130). Wiley-Blackwell.

- McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What gestures reveal about thought. University of Chicago Press.

- Mondada, L. (2014a). Cooking instructions and the shaping of things in the kitchen, and M. Nevile (Ed.), Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 199–226). John Benjamin.

- Mondada, L. (2014b). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137–156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.04.004

- Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

- Mondada, L. (n.d.). Conventions for multimodal transcription. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://mainly.sciencesconf.org/conference/mainly/pages/Mondada2013_conv_multimodality_copie.pdf

- Mori, J., & Hayashi, M. (2006). The achievement of intersubjectivity through embodied completions: A study of interactions between first and second language speakers. Applied Linguistics, 27(2), 195–219. doi:10.1093/applin/aml014

- Mortensen, K. (2016). The body as a resource for other-initiation of repair: Cupping the hand behind the ear. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1126450

- Müller, C. (2014). Gestural modes of representation as techniques of depiction. In C. Müller, A. Cienki, E. Fricke, S. Ladewig, D. McNeill, & S. Tessendorf (Eds.), Body, language, communication. Volume 2: An international handbook on multimodality in human interaction (pp. 1687–1701). De Gruyter.

- Oloff, F. (2018). ‘Sorry?’/‘Como?’/‘Was?’: Open class and embodied repair initiators in international workplace interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 126, 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.11.002

- Olsher, D. (2004). Talk and gesture: The embodied completion of sequential actions in spoken interaction. In R. Gardner & J. Wagner (Eds.), Second language conversations (pp. 221–245). Continuum.

- Preston, A., Balaam, M., & Seedhouse, P. (2015). Can a kitchen teach languages? Linking theory and practice in the design of context-aware language learning environments. Smart Learning Environments, 2(9), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-015-0016-9

- Schegloff, E. A. (1984). On some gestures relation to talk. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 266–296). Cambridge University Press.

- Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1977.0041

- Seo, M.-S., & Koshik, I. (2010). A conversation analytic study of gestures that engender repair in ESL conversational tutoring. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(8), 2219–2239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.01.021

- Sidnell, J. (2013). Basic conversation analytic methods. In T. Stivers & J. Sidnell (Eds.), The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 77–99). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Skedsmo, K. (2021). How to use comic-strip graphics to represent signed conversations. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(3), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2021.1936801

- Streeck, J. (2009). Gesturecraft: The manu-facture of meaning. John Benjamin.

- Stukenbrock, A. (2014). Take the words out of my mouth: Verbal instructions as embodied practices. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 80–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.08.017