ABSTRACT

Rules of behavior are fundamental to human sociality. Whether on the road, at the dinner table, or during a game, people monitor one another’s behavior for conformity to rules and may take action to rectify violations. In this study, we examine two ways in which rules are enforced during games: instructions and reminders. Building on prior research, we identify instructions as actions produced to rectify violations based on another’s lack of knowledge of the relevant rule; knowledge that the instruction is designed to impart. In contrast to this, the actions we refer to as reminders are designed to enforce rules presupposing the transgressor’s competence and treating the violation as the result of forgetfulness or oversight. We show that instructing and reminding actions differ in turn design, sequential development, the epistemic stances taken by transgressors and enforcers, and in how the action affects the progressivity of the interaction. Data are in German and Italian from the Parallel European Corpus of Informal Interaction (PECII).

Rules of behavior are fundamental to human sociality. Although scholars may disagree over the ontology and etiology of rules (Wilson, Citation1970), most would agree that human action is driven by rule following as much as it is by the pursuit of individual goals. Also, rules not only regulate but also sometimes constitute the very activities and behaviors they regulate (Garfinkel, Citation1963; Rawls, Citation1955; Searle, Citation1969). Rules are so central to social life—from traffic rules to table manners, from public health regulations to the rules of turn-taking—their existence is part of what defines human behavior (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, Citation1989).

A central concern of ethnomethodology and conversation analysis is how rules are locally applied and interpreted by participants (Garfinkel, Citation1967; Sacks, Citation1992). Because rules are susceptible to situational contingency, exceptions, and ambiguity (Kripke, Citation1982), even when the majority of participants generally agree on what constitutes a given rule, they may still disagree on whether, in a particular instance, the rule has been respected or broken (Leach, Citation1964; Liberman, Citation2013). Even in games, codified rules are generally not “sufficient to cover all the problematical possibilities that may arise” (Garfinkel, Citation1963, p. 199). Also, players of a game may have different degrees of acquaintance with the rules, or different customs or habits in interpreting them. For all these reasons, the application of rules requires constant coordination among participants.

Although this process is often managed tacitly, there are times when rules are explicitly thematized in interaction. In this study, we are particularly interested in such events as they occur during games played among family members and friends. Games are a central arena for the expression of human sociality, including attitudes and practices surrounding fairness, reciprocity, and the management of deviant behavior (DiCicco-Bloom & Gibson, Citation2010; Ensminger & Henrich, Citation2014; Garfinkel, Citation1963). Everyday games abound with sequences of interaction in which a player intervenes to enforce a rule that another player has violated. As such, they give us an environment in which participants consistently monitor one another’s behavior for conformity to rules and take action to rectify untoward behavior.

When a player violates a rule, an important concern for others is to judge whether the violation was deliberate or accidental. The deliberate violation of a rule is an occasion for sanctioning and moralizing; the accidental violation of a rule, on the other hand, is an occasion for helping another rectify his or her behavior and restoring the normative course of an activity. Unlike calling someone out for cheating or manipulating (Hofstetter & Robles, Citation2019), the actions taken by players to enforce rules in our study treat violations as accidental rather than deliberate. At the same time, these actions differ in whether they orient to the transgressor as someone who lacks knowledge of the relevant rule or as a competent player who momentarily forgot about it.

We build on previous research on how people manage unknowing violations of game rules. Svensson and Tekin (Citation2021) analyzed (projectable) violations of rules of turn-taking in games of pétanque, focusing on actions that were “not treated as done with an intention to cheat … but as a consequence of lack of knowledge about the rules” (p. 27). Another recent study by Zinken et al. (Citation2021) focused on the use of impersonal deontic statements (e.g., “It is not allowed to do X”) in the context of board games and found that they are “specifically used to instruct a player who is treated as having insufficient knowledge of the rules” (p. 2). This previous research suggests that, in different game contexts, players address and rectify untoward behavior that is attributable to a lack of knowledge of the relevant rules.

Research on epistemics shows that, not only in games but in interaction generally, people are sensitive to who knows what and who knows better, and to how access and rights to knowledge are expressed in the design of actions (Hayano, Citation2013; Heritage, Citation2012; Heritage & Raymond, Citation2005; Kamio, Citation1994, among many others). Epistemic positioning is often operationalized as a contrast between who knows or knows better (K+) and who does not know or knows less (K–). But a person’s state of knowledge in a given domain can be more nuanced: for example, when we put it in a temporal perspective. Consider the process of learning to drive. In early driving lessons, teachers have to instruct students who have little or no idea how to perform certain actions; in later driving lessons, teachers may only need to remind students of procedures they are already familiar with but may occasionally fail to implement (Deppermann, Citation2018a). This research shows that the design of teachers’ instructional directives changes as students become increasingly more competent.

The example of driving lessons also helps to illustrate how a person’s knowledge of an activity is bound up with his or her agency in that activity. As a student’s familiarity with driving techniques and the rules of the road increases, so does his or her autonomy in composing and executing driving moves, as well as his or her responsibility for failing to drive properly. This is reflected in how instructors and students account for driving errors: Whereas a beginner’s error is typically explained by the instructor, an experienced student’s error may be followed by the student’s own account of what he or she was trying to do (Deppermann, Citation2018b). In the present study, we show that similar dynamics of agency can be found in the management of rule violations during games.Footnote1

We examine two types of action—instructions and reminders—both of which treat a co-player as having unknowingly or inadvertently violated a rule. At the same time, the two actions differ in whether the transgressor is understood as having no knowledge of the rule at all or, alternatively, as being knowledgeable in principle but having forgotten or overlooked the rule at that moment. We show that instructions and reminders differ in turn design, sequential development, the epistemic stances taken by transgressor and enforcer, and in how the action affects the progressivity of the interaction. We conclude by considering the implications these actions have for the relationship between participants.

Data and methods

Our study is part of a larger project looking at the instantiation and reproduction of rules, norms, and morality in different languages and cultures based on data from the Parallel European Corpus of Informal Interaction (Kornfeld et al., Citation2023). The corpus consists of video recordings of the same types of everyday activities among speakers of English, German, Finnish, French, Italian, and Polish.Footnote2 Types of activities include having a meal (breakfast), playing (a tabletop game), and chatting (during a car trip). From this corpus, the study focuses on game interactions in German and Italian. Initial observations of similarities in the way speakers of the two languages behaved in episodes of rule enforcement led us to build a joint collection, following the approach of cross-linguistic “co-investigations” (Lerner & Takagi, Citation1999).

We identified sequences in which a player intervenes to address an ongoing or projectable rule violation by another player, the structure of which can be schematized as follows:

Ongoing or projectable rule violation by Participant A (the “transgressor”);

Participant B (the “enforcer”) intervenes to enforce the rule;

Participant A complies and/or responds to the enforcement.

Sequences of this kind give us a recurrent context in which conformity and deviance are managed by participants, and rules are explicitly thematized. In this context, we observe a range of actions that enforcers can take, the most frequent being instructions and reminders.Footnote3 These actions are responded to in different ways by the transgressor and are reflected in how the sequence develops after the enforcement.

We identified rule enforcement sequences across 21 recorded interactions for a total of about 19 hours of data. Of these interactions, eight were among German speakers (about 8 h) and 13 were among Italian speakers (about 11 h). Our collection yielded a total of 50 instructions (27 German, 23 Italian) and 75 reminders (23 German, 52 Italian).

The data were analyzed using conversation-analytic methods (Sidnell & Stivers, Citation2013). Transcripts follow GAT 2 conventions (Selting et al., Citation2009) as well as Mondada’s (Citation2019) conventions for representing embodied behavior. Particles and idiomatic phrases were translated with the closest English expression (e.g., German achso ≈ “oh I see” Italian eh certo ≈ “well of course”). The reader should bear in mind that these free translations are approximations, especially where particles are identified as such (PTC) in the interlinear morphemic gloss.

Enforcing rules with instructions

In instruction sequences, Participant B's (the enforcer's) intervention extends beyond rectifying Participant A’s (the transgressor’s) behavior and involves formulating the relevant rule for him or her to learn (Zinken et al., Citation2021). Instructions are typically designed with impersonalizing and generalizing language that transcends the present moment. This goes hand in hand with the enforcer assuming a position of epistemic primacy over the rules of the game, congruent with the transgressor’s displays of epistemic subordination. Finally, instructions are typically produced over the course of multiple TCUs/turns and thus impact the progressivity of the game, which is disrupted in the service of imparting knowledge.

Extract (1) is from a game of Settlers of Catan, in which players trade resources to build settlements on the board. When the extract begins, Gabriel draws a “development” card, reads it, and considers it for a few moments (lines 1–3). He then proceeds to play it (line 4) but, as he does so, Karl intervenes (lines 5–6).

(1) PECII_DE_Game2_20151113 (German)

As Gabriel proceeds to make his move (line 4), Karl interjects (äh moMENT momEnt, “uh hold on hold on,” lines 5–6). Gabriel responds by putting a hand back on the card he has just laid down for playing, initiating a retraction of the move. Then, as Karl continues to talk (line 7), Gabriel drops the road pieces on the table and picks the card back up, completing the retraction.

Looking more closely at Karl’s talk, after interjecting into Gabriel’s move with a first TCU (äh moMENT momEnt, “uh hold on hold on,” lines 5–6), prompting the move’s retraction, he goes on to produce a second TCU (das kannste ERST nächste runde ausspielen, “you can play that in the next round at the earliest”). During this second TCU, Gabriel’s retraction is ongoing, and the personal deontic design of the statement, coupled with a pointing gesture in Gabriel’s direction, anchors Karl’s talk to what Gabriel has just done. At the same time, Gabriel’s verbal response treats Karl’s action as an instruction. By saying achSO, (“oh I see”) and raising his eyebrows (line 8; Dix & Groß, Citationin press), Gabriel marks an understanding of new information being given to him (Golato & Betz, Citation2008) and displays surprise at it (Wilkinson & Kitzinger, Citation2006).

The interaction continues as Julia invites expansion of the sequence with a newsmark (JA? “yes,” line 10). Karl responds by confirming (ja. “yes,” line 12) and then restating the rule more generally: wenn du ne KARte hast darfst du die erst NÄCHSte runde ausspielen. (“if you have a card you may play it in the next round at the earliest,” lines 14–15). The generic nature of this second formulation is reflected in a number of design features, including its conditional construction, the use of an indefinite reference (ne KARte, “a card”), and the use of generic “you” (Auer & Stukenbrock, Citation2018).

Consider another case, from a card game. As Rocco and Guido play their cards and complete the current hand (lines 1–2), Elio begins to gather the pot, claiming the hand for his team. However, Guido halts Elio’s move (‘pEta ‘PEta:; “wait wa:it”), reaching for the cards Elio is taking (line 4) and stopping him in his tracks (line 5). As Guido moves the cards from Elio’s side of the table, he goes on to explain that the current hand actually belongs to Elio’s opponents (che l’è NOstro quEsto. “because this is ours”). A moment later, Elio initiates repair (COSsa. “what”) and Guido’s teammate Rocco gets involved, building on Guido’s intervention to produce an instruction.

(2) Circolo02_734707 (Italian)

Similar to (1), the sequence here develops such that the enforcement of the rule precedes its formulation. First, the enforcer (Guido) stops and rectifies the transgressor’s (Elio’s) violation (lines 4–5). Then, the rule is formulated (lines 8–10), in this case by another participant (Rocco). We can also notice that, although both parts of the sequence involve the provision of accounts, the account given during the enforcement is specific to the present situation (“because this is ours”), whereas the subsequent account abstracts away from it (“because the king always trumps the knight”). Moreover, as the sequence unfolds, the transgressor’s behavior reflects a position of epistemic subordination. After aligning with the enforcement by retracting his hand (line 4), Elio first initiates repair (COSsa. “what,” line 7) and then produces a change-of-state token (Heritage, Citation1984; ↑A:H;, “↑o:h”). Note also his use of the connective aLOra. (“then”) in response to the instruction (line 11), indicating that his compliance follows from a new understanding of the situation.

It bears emphasis that, in (2) as in (1), it is the enforcer, or another player with knowledge of the rule, who explains the violation; no account comes from the transgressor, who instead mainly receipts the instruction as news. Participants thus do not treat accountability as lying with the transgressor.

In a third case, also from a card game, Clara is playing a card (en TRE:, “a three” line 1) to add to a combination on her teammate Silvia’s side of the table. After checking that the combination does, indeed, belong to their team (lines 3–4), Clara completes the move and announces that she is going to wait to draw a card until the next round (‘dEso speTEM a caVAR, “now we wait to draw,” line 8). In response, Bianca intervenes to rectify Clara’s behavior.

(3) Circolo01_1992230 (Italian)

The target turn by Bianca (lines 10–12) has three components: an objection to Clara’s announcement (↑no NO? “no no”), a directive to draw a card (ti TOlo ‘l tUo; “you take yours”), and an account for it (≪l>che te sEi la PRIma.>, “because you are the first”).

Although Bianca’s turn is not followed by a more abstract formulation of the rule as we saw in (1) and (2), its design bears the marks of an instruction. First, it consists of two separate TCUs, marked by falling intonation at the end of the directive (line 10) and, in this particular case, also by a lower pitch register across the subsequent TCU (line 12). Note also that the first TCU is sufficient to change the course of Clara’s actions, as she begins to comply by reaching for the deck. At this point, the reason Bianca gives for Clara having to draw a card (“because you are the first”) extends beyond enforcing the rule: It presents the rule as something Clara needs to be coached in.

The continuation of Clara’s response is also consistent with an instruction. Her repetition of Bianca’s “no” (line 11) is prefaced by a change-of-state token (↑ah, “oh”) and accompanied by an eyebrow raise, indicating surprise or at least the unexpectedness of having to change course (see also Gabriel’s eyebrow raise in (1)).

Finally, note that, although Clara begins to comply during Bianca’s directive by reaching for the deck (line 10), she then pauses, holding a hand on the deck (line 12) and gazing at Bianca until she is done speaking (line 14). Besides showing recipiency during the instruction, Clara’s behavior here is indicative of the diminished agency of transgressors in instruction sequences: The execution of their next action is often subordinated to the enforcer’s completion of the instruction. As we will see, this contrasts with the agency displayed by transgressors in reminder sequences.

In sum, we have seen that instruction sequences have certain distinctive features. As Participant B intervenes to enforce a rule, he or she does more than halting and rectifying Participant A’s behavior: He or she formulates the relevant rule both to account for the intervention and to impart knowledge of the rule. This is often achieved through grammatical and lexical features that impersonalize and generalize the enforcer’s talk. The way that the enforcer halts or slows the activity to produce the instruction over the course of multiple TCUs/turns disrupts progressivity in favor of imparting knowledge. Whereas the enforcer takes a position of epistemic primacy with respect to the rule, the transgressor is treated as lacking knowledge of it. This diminishes the transgressor’s agency, with consequences for accountability: In instruction sequences, transgressors do not explicitly account for their actions, whereas enforcers explain their interventions. Participants thus orient to someone’s lack of knowledge as the reason and justification for the violation.

Enforcing rules with reminders

We now offer an analysis of reminding as a distinct type of action people can take to address a violation and enforce the relevant rule. We show that reminding actions systematically differ from instructions in turn design, sequential development, the epistemic relation between participants, and with respect to the game’s progressivity.

Consider (4), from another game of Settlers of Catan. After stepping away from the table for a moment, Carlina comes back and checks what has happened in the meantime (lines 1–9). She then goes on to announce her move (line 12) but, even before she is done speaking, Janosch intervenes to enforce a rule (lines 13–14).

(4) PECII_DE_Game2_20171026 (German)

As Carlina gets back into the game, she looks at her cards (starting in line 6) and then announces her intention to build something (line 12). Before her announcement is complete, however, Janosch intervenes to halt her incipient move (HALT du bis- du musst erstmal würfeln. “hold on you ar- you have to roll first,” lines 13–14).

There are several aspects of Janosch’s turn worth noting here. One is that the turn cuts into Carlina’s talk before she has reached a transition-relevance place: This prioritizes the rectification of Carlina’s behavior over the completion of her talk, conveying urgency. Another aspect is that the turn consists of a single TCU, with no prosodic features (e.g., sound stretching or a drop in pitch) separating the grammatical units HALT (“hold on”) and du bis- du musst erstmal würfeln. “you ar- you have to roll first.” Further, the turn both refers and is addressed to Carlina specifically. Janosch gazes at her directly and, unlike in (1), there are no co-occurring features suggesting that the second person du (“you”) should be understood generically here. Instead, the personal deontic construction (du musst erstmal würfeln. “you have to roll first”) expresses what Carlina ought to do here and now.

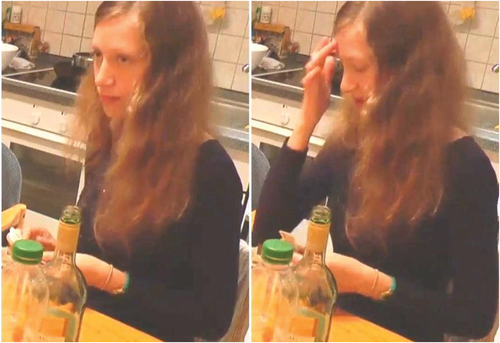

Beyond Janosch’s turn, more evidence for the distinctive nature of the action being accomplished here is found in Carlina’s response, displaying “just-now recollection” (Betz & Golato, Citation2008; Küttner, Citation2018). By saying ja STIMMT; (“yes right,” line 15), she expresses a realization and at the same time claims independent epistemic access to what she has just been told (Betz, Citation2015). Also, Carlina accompanies this spoken turn with a symbolic gesture: a tap on the forehead while closing the eyes and/or looking down ().Footnote4 This gesture further embodies Carlina’s claim of having recollected something already known to her, while admitting to having momentarily forgotten about it.

Figure 1. Frames from (4), lines 14–15. In (1a), Carlina is looking at Janosch; in (1b), she closes her eyes and/or looks down while saying ja STIMMT; (“yes right”) and making a “head tap” gesture with the tips of the fingers.

Note finally that, right after tapping on her forehead, Carlina immediately grabs the die to roll it, showing that she does not need elaboration on the rule before resuming the game.

In sum, the way that Participant B intervenes to enforce the rule here is quite different from what we saw in the previous section. For one thing, his action is produced within a single TCU, rather than across multiple TCUs or turns. Coupled with its early onset relative to A’s talk, the design of B’s turn in (4) prioritizes the progressivity of the game, jumping in to rectify A’s behavior without adding further explanation. As for the transgressor’s behavior, her immediate response is to claim independent epistemic access to what the enforcer has said (ja STIMMT; “yes right”), followed by swift compliance. In this particular case, the transgressor’s epistemic stance is strengthened by a “head tap” gesture that not only claims prior knowledge of the rule but also acknowledges a failure to act on it. This gesture epitomizes the distinct import that reminder sequences have for the transgressor’s accountability relative to the rule violation. More generally, the transgressor’s behavior in this case shows greater agency compared to instruction sequences: After owning up to the violation, she acts swiftly, without waiting for the enforcer to say more.

The next case is from a game of Monopoly, in which Enrica intervenes to remind her boyfriend Mattia that, after rolling the dice once (line 1), he ought to roll a second time (line 15).

(5) PECII_IT_Game_20161222_01_2395518 (Italian)

As Mattia rolls an eight (two fours), Alba moves the token for him (lines 4, 8). The token lands in an area of the board dominated by Furio’s property, and the particular space where the token ends up requires Mattia to pay Furio $1,200 (line 11). After reacting somewhat surprised and possibly dismayed at the amount (tsk MILle due addiritTUra:s:. “one thousand two {hundred} fancy that,” line 13), Mattia proceeds to pay Furio: He counts the money and places it in an area of the table between them (lines 13–15). Meanwhile, Enrica, whose turn is after Mattia’s, begins to reach for the dice (line 13). Looking at the dice, however, she notices that Mattia has rolled two fours—a double—which means that he has to roll again.Footnote5 So she reminds him: e devi ritiRA:re stronZETto_ (“and you have to roll again little shit,” line 15).

Because Mattia is still in the process of paying Furio, it is unclear how Enrica is able to anticipate his failure to roll the dice a second time. Note, however, that just prior to her turn, she reaches for the dice, only to suddenly retract her hand (line 13). This suggests that she herself was not aware of Mattia’s double, and that she may have expected Mattia to announce it when he called out the number he rolled (OTto; “eight,” line 6). Regardless, Mattia’s response treats Enrica’s action as a reminder (ah SÌ.=son DUe. “oh yes they are two”). The turn-initial ah SÌ. (“oh yes”) contains a change-of-state token combined with affirmation (Betz & Golato, Citation2008; Seuren et al., Citation2016), claiming his recollection of something he knows independently. Moreover, his subsequent son Due (“they are two”) demonstrates independent access to the rule that Enrica is enforcing. While saying this, Mattia swiftly complies (lines 17–18) and neither he nor other players seek elaboration on the issue, thus promoting the progressivity of the game.

Back to the design of Enrica’s reminder, it is consistent with what we saw in the previous case: a single TCU with a personal deontic construction expressing what Mattia ought to do. In addition, the reminder includes a turn-final, expletive address term (stronZETto_, “little shit”). This address term accomplishes a few things. First, it emphasizes that the obligation to roll again here refers specifically to Mattia, in the present situation. Second, post-positioned address terms are typically implicated in “expressive actions” (Clayman, Citation2010), conveying a particular stance toward the recipient (Lerner, Citation2003). This is made rather clear here by the expletive form, which can be understood in light of the ongoing banter and competition between the couple (see lines 1–5). Overall, Erica’s use of stronZETto_ (“little shit”) contributes to taunting Mattia with his failure to remember that he has to roll the dice again. Also, as a turn-final address term, it marks off the end of Enrica’s action and does not project continuation (e.g., to explain why Mattia ought to roll again).

Consider now another case in which the basic linguistic practice used for producing a reminder is different, but the interactional import of the action is analogous. The case is from the same game of Monopoly. After rolling the dice (lines 2, 4), Mattia moves his hand toward the board (line 5), indicating an intention to move his game piece, which is confirmed by his subsequent question (dov’È il mIo; “where is mine,” line 7). Alba then intervenes by pointing out that Mattia is “in jail” (line 7). This means that he is not allowed to move his piece until he rolls a double or uses another strategy to get out of jail. A moment later, Alba repeats the same statement to stop Furio from moving Mattia’s piece on his behalf.

(6) PECII_IT_Game_20161222_01_2891744 (Italian)

Similar to (4) and (5), the transgressor’s response here aligns with the enforcer’s reminder by claiming independent knowledge of the state of play while abandoning the rule-infringing move. In this case, we have two responses of this kind, first by Mattia (A:H sÌ; “o:h yes,” line 9) and then by Furio (A:H giUsto è vEro; “o:h right that’s true,” line 11), who was in the process of moving Mattia’s piece on his behalf (lines 6, 11). Note that Furio’s response conveys an even stronger epistemic claim by overtly confirming what Alba has said (Heritage & Raymond, Citation2005). The combination of a change-of-state token with asserting the rightness or veracity of something is a distinct way of displaying “just-now recollection” of “something previously known, but momentarily forgotten” (Küttner, Citation2018, p. 118).

What distinguishes (6) from the reminders seen above is the linguistic practice used by the enforcer (sei in priGIOne, “you’re in jail”), a factual declarative (Rossi, Citation2018). By not specifying what the transgressor ought (not) to do, foregrounding instead a factual reason for (not) doing it, the enforcer relies on the recipient to infer what the problem is, be reminded of the relevant rule, and arrive at a solution on his own. A factual declarative, in other words, attributes the transgressor more agency than a modal declarative.

There are two more aspects of this case that are worth noting. One is the post-positioned address term in Alba’s first version of the reminder for Mattia (sei in priGIOne cAro; “you’re in jail dear,” line 6), which contributes to situate and personalize the action (see also (5)). Another aspect is that, upon pursuing compliance from another participant—Furio, who has touched Mattia’s piece to move it on his behalf (lines 6, 11)—Alba does not modify the practice she initially selected to enforce the rule. Instead, she repeats it verbatim, louder, without the address term. In so doing, Alba orients to the appropriateness of her reminding action in this context. As we will see in the next section, a transgressor’s failure to immediately comply with or display understanding of a reminder creates an opportunity for the enforcer to expand on and potentially transform the action. But this does not happen here: Alba sticks to the same turn design (not even changing the deixis from “you” to “he” even though the addressee has changed), thus orienting to Furio’s competence about the rule and autonomy in correcting himself.

In sum, we have identified certain distinctive features of reminder sequences that stand in contrast with what we find in instructions. First, reminders are designed with a single TCU. Whether in the form of a personal deontic declarative (e.g., “you have to roll first”) or a factual one (e.g., “you’re in jail”), reminders do not elaborate on why participant A should comply with the enforcement. Instead, progressivity is prioritized by both participants, with Participant A quickly resolving the issue without seeking elaboration. A reminder treats Participant A as competent about the rule being violated. Congruent with this, Participant A responds by claiming independent knowledge of the rule and an understanding of the conditions of its violation. This may be accompanied by an acknowledgment of A’s failure to act on his or her knowledge.

Taken together, these elements reflect the greater agency attributed to transgressors in reminder sequences, in direct contrast with what we saw in instruction sequences. One aspect of agency is accountability (Kockelman, Citation2007). In instruction sequences, it is enforcers who account for their intervention; in reminder sequences, it is transgressors who acknowledge their failure to follow a rule. Agency also encompasses the formulation and execution of the transgressor’s next action following the violation. Whereas in instruction sequences the next action is often subordinated to the completion or elaboration of the instruction, in reminder sequences it is executed swiftly; and where the enforcer intervenes with only a factual description (e.g., “you’re in jail”), the transgressor demonstrates an ability to autonomously formulate or “author” (Goffman, Citation1981) the solution to the problem. Finally, the language of reminding lacks the impersonalizing and generalizing features that characterize instructions as transcending the present situation. Reminders are firmly anchored in the here and now, including in the way they are addressed to and made relevant for the transgressor specifically, at that moment.

Negotiating the terms of rule enforcement

In this section, we build on what we have learned about enforcing rules with instructions and reminders to examine cases in which the terms of rule enforcement are negotiated between participants. These cases give us a window into the normativity of instructing and reminding as distinct actions, and into the consequences these actions have for the interaction and for the relation between participants, particularly with regard to their respective knowledge and agency in the game. We will see that a rule enforcement sequence that begins with a reminder may be contingently expanded in light of the transgressor’s response, resulting in a transformation from reminding to instructing and/or a negotiation between the two (7, 8). We will also see that enforcing a rule with an instruction can be met with resistance when the action fails to recognize the transgressor’s prior knowledge of the rule (9).

The first case is from another game of Settlers of Catan. The extract begins as Samu requests confirmation that he can build structures on the board only after rolling the dice (lines 1–2). Although the turn is declaratively formatted and ends with ovviaMENte; (“obviously”), he delivers it while gazing at Matteo (Stivers & Rossano, Citation2010), who responds by confirming (line 3). Samu then produces a sequence-closing third (eh CERto, “well of course”) that treats the answer to his earlier question as self-evident. In this question-answer sequence (lines 1–5), then, Samu displays an ambivalent epistemic stance about the rules of the game, at once showing and denying uncertainty. A moment later, he goes on to make his move, placing a piece on the board to claim the space as a newly built colony (lines 7–8). Looking on, Plinio first produces a standalone click (line 10) and then states non PUOi. (“you can’t,” line 12). Our focus is on how the rule enforcement sequence develops from this point onward.

(7) PECII_IT_Game_20151030 (Italian)

Plinio’s intervention is initially designed as a reminder: After anticipating his objection to Samu’s move with a standalone alveolar click (Ogden, Citation2020), he produces a single TCU with a minimal personal deontic statement (non PUOi. “you can’t”). As we saw in the previous section, rule enforcements of this kind make it possible for the transgressor to quickly remedy the violation based on his or her recollection of the relevant rule, and to demonstrate or claim independent knowledge of it as he or she does so.

Samu’s response here, however, departs from the kinds of uptakes examined in the previous section. What he says (non POSso metterla lì VEro; “I can’t put it there can I”) contains a repetition of Plinio’s statement with deictic shifts (non POSso, “I can’t”) and the addition of what Plinio has left implicit (metterla lì, “put it there”), followed by the turn-final tag VEro;, lit. “true,” roughly “can I” in this context. Although the modified repeat claims some epistemic authority over what Plinio has told him (Stivers, Citation2005), the turn as a whole invites confirmation and elaboration. This sets in motion a transformation of the intervention from reminding to instructing.

Plinio first confirms Samu’s modified repetition (NO_ “no,” line 15) and then immediately proceeds to explain why Samu cannot build a colony there (questi DUe hanno monopolizzAto la: COsa., “these two have monopolized the: thing,” line 17). In overlap with this, Matteo too begins to explain (dev’ESsere una:_, “it must be one:,” line 16) but abandons the turn in favor of Plinio’s. Plinio subsequently extends his turn with another TCU (=non si puÒ:_, “it’s not allowed to:”), which is left incomplete. Note that both Plinio and Matteo use impersonalizing language here—“it must be one,” “it’s not allowed to”—as is typical of instructions.

At this point, Samu responds by claiming recollection and independent access to the rule (A:H è VEro, “o:h that’s true,” line 19), thus recasting his position as more knowledgeable. A moment later, however, he also treats the constraint on his move as both unfortunate and unexpected (manNAGgia:; “da:mn”). The sequence continues with Matteo further instructing Samu on what his options are, using a conditional construction (see also (1)) (“if you’re going to build a colony you can only put it here,” lines 20–21). In the closing of the sequence, Samu once again claims independent access to what has been just explained to him (E:H per FO:Rza, “yeah it’s necessarily so,” line 22) as well as autonomy in determining what his next move is going to be (è proprio quello che faRÒ. “that’s exactly what I’m going to do,” line 23).

In sum, the complex development of this case shows that the transgressor’s response to the enforcer’s reminder is sometimes a turning point for the sequence to be expanded and for the intervention to be transformed into an instruction. At the same time, we also see that the terms of a rule enforcement may continue to be negotiated by players as the sequence unfolds, with the transgressor shifting between a position of epistemic subordination and one of greater epistemic authority and agentivity.

Consider another case. Gioia, Sandro, Angelo, and Milo are playing a game of Ticket to Ride, in which the goal is to build railroad routes between cities on a map. When the extract begins, Gioia is talking through her move, announcing that she will build a railroad section by placing a piece on the board (lines 1–6) and handing a card over to Angelo for this purpose (lines 6–8). Gioia then anticipates continuing her turn with another move (“and then,” line 9) but gets interrupted by Sandro (“that’s it,” line 11). This is where the focal sequence begins.

(8) PECII_IT_Game2_20180325_Ticket (Italian)

As in the previous case, Participant B’s intervention is initially designed as a reminder, consisting of a single TCU (BASta. “that’s it”), in this case, a minimal description of the fact that Participant A has exhausted her turn. Sandro subsequently adds to the reminder contingent on Gioia’s responses. Her first response (NO. “no”) may have been intended as a negative answer—treating Sandro’s BASta. (“that’s it”) as a question—or it may have been intended as an objection to Sandro’s attempt to halt her move. Regardless, Sandro follows up by saying non PUOi. (“you can’t,” line 13), and Gioia goes on to question the grounds on which her move is being halted (COme; “how come,” line 14) with an astonished face (open mouth and slightly raised eyebrows). At this point, Sandro adds an explanation for why Gioia’s turn is over: She can build railroad segments only uno alla VOLta. (“one at a time,” line 13).

So, in (8) as in (7), we see the gradual expansion of a reminder into an instruction, contingent on the transgressor’s response to the intervention. At the same time, we also see participants taking competing stances as to the transgressor’s competence and accountability for violating the rule. On one hand, Gioia pursues her challenge not only to Sandro’s enforcement (≪:-)>CO:me.>, “how come,” è in un’aZIOne:? “it’s within an action,” lines 21, 24) but also to the rule itself (che PIZza. “what a drag,” chi È che ha fatto sta REgola; “who made this rule,” lines 27, 29), although these later comments also convey her resignation and previous unawareness of the rule.

On the other hand, from the moment Gioia begins to object to Sandro’s intervention (line 12), Angelo takes a different and more critical stance toward her. Instead of aligning with Sandro’s shift toward instructing Gioia (e.g., by confirming or adding to Sandro’s explanation), Angelo pushes back on her objection, conveying that she should know better (E:::H adE:s; “we:::ll no:w,” no NO, “no no,” lines 15, 17). Angelo maintains this critical stance through the rest of the interaction: He responds to Gioia’s subsequent ≪:-)>CO:me.> (“how come,” line 21) with an eh-prefaced SÌ:; (roughly “well yeah”) and then rejects her contention that the disallowed move was within the same “action” (line 24) with a dismissive series of clicks expressing negation and/or disapproval (line 25). In sum, the negotiation that follows Sandro’s intervention reveals a tension between the extent to which Gioia should be treated as a less knowledgeable player who needs instructing and the extent to which she is, in fact, a sufficiently competent player who should know better.

In a last case, we see Participant A resisting Participant B’s instruction, demonstrating the implications instructing has for a player’s knowledge and agency. The case is from the same game of Settlers of Catan seen in (1). In the focal sequence, Karl enforces a rule being violated by Gabriel with an instruction (lines 12–13). In response, Gabriel pushes back against the instruction by asserting both independent knowledge of the rule and control over his next move.

(9) PECII_DE_Game2_20151113 (German)

When the extract begins, Gabriel is wondering where to place his game piece (line 1). As he finally puts it on the board (lines 9–10), Karl intervenes by saying =äh das das GEHT nich; (“this is not possible,” line 12), pointing across the board to Gabriel’s piece. The impersonal deontic design of this first TCU already indicates the instructional character of Karl’s action. Before its completion, Gabriel picks the piece back up (line 13) and, during Karl’s second TCU, begins to reposition it (lines 13–16). In his second TCU, Karl spells out the relevant rule: äh du musst immer ZWEI abstand (halten); (“you must always maintain a distance of two”), with the generalizing adverb immer (“always”) adding to the features that mark his action as an instruction.

In overlap with this, however, Gabriel asserts independent knowledge of the rule and understanding of the situation: das geht nich, AH ich muss zwEI abstand haben,=ne, (“this is not possible AH I must hold a distance of two=no?” line 14). The question tag ne (“no?”) invites a response, which Karl latches onto the second part of his overlapping turn (=geNAU; “exactly,” line 13; Oloff, Citation2017).

Rather than dropping out of the overlap and displaying recipiency to Karl’s instruction (cf. (3)), Gabriel positions himself as knowing what was wrong with his move, formulating the rule almost simultaneously as Karl. A moment later, Gabriel says jaja hier’s (aber) oKE- (“yesyes here is okay (though),” line 16). The turn-initial jaja (“yesyes”) (Barth-Weingarten, Citation2011) is another indication of Gabriel’s resistance to Karl’s instruction, whereas the statement “here is okay (though)” shows his ability to evaluate the appropriateness of his next move. Although his subsequent turn (line 20) invites a response with the tag ne (“no?”), it also displays understanding of another rule (“I’m allowed to put two”), to which Karl responds, once again, by contending with Gabriel’s claim of epistemic authority (“you’re allowed to put two right”; Heritage & Raymond, Citation2012).

To sum up, the cases examined in this section show that players may take competing stances as to the transgressor’s knowledge of the rules, and whether he or she should be instructed or reminded. In (7) and (8), the enforcer shifts from reminding to instructing contingent on the transgressor’s response to the intervention, which has indicated a need for explanation. At the same time, the extent of the transgressor’s knowledge and agency continue to be renegotiated in the rest of the sequence. In (9), we see a reverse scenario in which the enforcer intervenes with an instruction but the transgressor resists it, claiming greater knowledge and agency than implicated by the enforcer’s action. By producing an instruction, the enforcer has cast the transgressor as less knowledgeable than he actually demonstrates to be.

Conclusion

Whether on the road, at the dinner table, or during a game, people monitor one another’s behavior for conformity to local rules and may take action to rectify violations. In this study, we have examined two ways in which rules are enforced during play: instructions and reminders. Building on prior research, we identify instructions as actions produced to rectify violations based on a lack of knowledge of the relevant rule, which the instruction is designed to impart. By contrast, the actions we refer to as reminders are designed to enforce rules presupposing the transgressor’s competence and treating the violation as the result of forgetfulness or oversight. We have shown that instructing and reminding actions differ in turn design, sequential development, the epistemic stances taken by transgressors and enforcers, and in how the action affects the progressivity of the interaction. These features are summarized in .

Table 1. Main Features of Instruction and Reminder Sequences.

Enforcing a rule with an instruction or a reminder is sensitive to another player’s knowledge and agency within a game. Instructions attribute violations to a lack of knowledge of the relevant rule and put the onus of explaining its enforcement on Participant B. In line with this, Participant A does not respond to the instruction with an account, because the reason for violating the rule is understood to be his or her lack of knowledge. In reminder sequences, on the other hand, accountability lies with Participant A. When Participant A responds to a reminder by claiming knowledge of the rule he or she has violated, the implication is that he or she has failed to act on it, which may be explicitly acknowledged.

The relation between knowledge and agency is further manifested when reminders are designed with minimal personal deontic declaratives (e.g., “you can’t”) or factual ones (e.g., “you’re in jail”). By not specifying what ought (not) to be done (e.g., “you can’t move in this turn”), the enforcer relies on the transgressor’s ability to infer what the problem is and autonomously determine its solution. For their part, transgressors can display agency by acting swiftly to remedy the violation or otherwise asserting control over their next move. This stands in contrast with transgressors waiting for the enforcer to complete or elaborate on an instruction.

Furthermore, we have shown that the distinction between instructing and reminding is normative, especially as it relates to epistemics. Enforcing rules with an instruction or a reminder is governed by a more “general rule that provides that one should not tell one’s co-participants what one takes it they already know” (Sacks, Citation1973, p. 139). The interactional consequences of this come to the fore in cases like (9), in which the transgressor resists being instructed, claiming greater knowledge of the rules than implicated by the enforcer. But the same principle can be seen in operation in cases like (7) and (8), where the enforcer intervenes with a reminder and only gradually shifts to an instruction contingent on the transgressor’s uptake.

We suggest that the distinction between instructing and reminding is not limited to games but extends to other activities governed by codified rules (e.g., driving). More generally, the socio-interactional import of instructing versus reminding is likely to be relevant in any context in which the way people monitor one another’s behavior for conformity to rules is sensitive to differentials in knowledge and agency.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our fellow members of the project, “Norms, Rules and Morality Across Languages” (NoRM-aL)—including Uwe-A. Küttner, Christina Mack, Jowita Rogowska, and Jörg Zinken—and to other colleagues at the Leibniz-Institute for the German Language, Mannheim—including Helena Budde, Alexandra Gubina, Nadine Proske, Silke Reineke, and Mojenn Schubert—for their input and intellectual engagement at various stages of this study. Special thanks go to Jörg Zinken and Uwe-A. Küttner for a careful reading of an earlier draft and many fruitful conversations since the inception of this study. We also benefited from the feedback we received from Emily Hofstetter, Jay Meehan, and audiences at the 2021 International Pragmatics Association (IPrA) Conference and at the 2021 American Sociological Association (ASA) Annual Meeting. This work was supported by the Leibniz Association under a Leibniz Cooperative Excellence Grant (# K232/2019 to Jörg Zinken).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Our conceptualization of the relation between knowledge and agency, and of different elements of agency (execution, composition, responsibility), follows Enfield (Citation2011), who draws on Goffman (Citation1981) and Kockelman (Citation2007).

2 Data were collected with the informed consent of participants.

3 Other, less common actions that we observe in this environment are complaints and accusations of cheating. These are not part of the analysis here as our focus is on violations that are treated as accidental rather than deliberate.

4 In other languages or contexts, this type of gesture may be performed by striking the forehead (a “head slap”) with the whole palm rather than with the tip of the fingers.

5 Rolling again puts Mattia once more at risk of landing on someone else’s property; not rolling again, on the other hand, puts that risk off until the next turn.

References

- Auer, P., & Stukenbrock, A. (2018). When ‘you’ means ‘I’: The German 2Nd Ps.Sg. Pronoun Du between genericity and subjectivity. Open Linguistics, 4(1), 280–309. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0015

- Barth-Weingarten, D. (2011). Double sayings of German JA—more observations on their phonetic form and alignment function. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 44(2), 157–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2011.567099

- Betz, E. (2015). Indexing epistemic access through different confirmation formats: Uses of responsive (das) stimmt in German interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 87, 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.03.018

- Betz, E., & Golato, A. (2008). Remembering relevant information and withholding relevant next actions: The German token achja. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(1), 58–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701691164

- Clayman, S. E. (2010). Address terms in the service of other actions: The case of news interview talk. Discourse & Communication, 4(2), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481310364330

- Deppermann, A. (2018b). Instruction practices in German driving lessons: Differential uses of declaratives and imperatives. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 28(2), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12198

- Deppermann, A. (2018a). Changes in turn-design over interactional histories – The case of instructions in driving school lessons. In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 293–324). John Benjamins.

- DiCicco-Bloom, B., & Gibson, D. R. (2010). More than a game: Sociological theory from the theories of games. Sociological Theory, 28(3), 247–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01377.x

- Dix, C., & Groß, A. (in press). Surprise about or just registering new information? Moving and holding both eyebrows as visual change-of-state markers. Social Interaction.

- Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. (1989). Human ethology. Aldine De Gruyter.

- Enfield, N. J. (2011). Sources of asymmetry in human interaction: Enchrony, status, knowledge and agency. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 285–312). Cambridge University Press.

- Ensminger, J., & Henrich, J. P. (Eds.). (2014). Experimenting with social norms: Fairness and punishment in cross-cultural perspective. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice Hall.

- Garfinkel, H. (1963). A conception of, and experiments with, “trust” as a condition of stable concerted actions. In O. J. Harvey (Ed.), Motivation and social interaction: Cognitive determinants (pp. 187–238). Ronald Press.

- Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Golato, A., & Betz, E. (2008). German “ach” and “achso” in repair uptake: Resources to sustain or remove epistemic asymmetry. Zeitschrift Für Sprachwissenschaft, 27(1), 7–37. https://doi.org/10.1515/ZFSW.2008.002

- Hayano, K. (2013). Territories of knowledge in Japanese conversation [Ph.D. dissertation]. Radboud University Nijmegen. http://repository.ubn.ru.nl/handle/2066/105826

- Heritage, J. (2012). Epistemics in action: Action formation and territories of knowledge. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.646684

- Heritage, J. (1984). A change of state token and aspects of its sequential placement. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 299–345). Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). The terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in talk-in-interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800103

- Heritage, J., Raymond, G. (2012). Navigating epistemic landscapes: Acquiescence, agency and resistance in responses to polar questions, and J. P. De Ruiter (Ed.), Questions. Formal, functional and interactional perspectives (pp.179–192). Cambridge University Press.

- Hofstetter, E., & Robles, J. (2019). Manipulation in board game interactions: Being a sporting player. Symbolic Interaction, 42(2), 301–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.396

- Kamio, A. (1994). The theory of territory of information: The case of Japanese. Journal of Pragmatics, 21(1), 67–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(94)90047-7

- Kockelman, P. (2007). Agency: The relation between meaning, power, and knowledge. Current Anthropology, 48(3), 375–401. https://doi.org/10.1086/512998

- Kornfeld, L., Küttner, U.-A., & Zinken, J. (2023). Ein Korpus für die vergleichende Interaktionsforschung: Das “Parallel European Corpus of Informal Interaction” (PECII). In Jahrbuch des Instituts für Deutsche Sprache 2022. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111085708-006

- Kripke, S. A. (1982). Wittgenstein on rules and private language: An elementary exposition. Harvard University Press.

- Küttner, U.-A. (2018). Investigating inferences in sequences of action: The case of claiming “just-now” recollection with oh that’s right. Open Linguistics, 4(1), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0006

- Leach, E. R. (1964). Political systems of highland Burma: A study of Kachin social structure. Athlone Press.

- Lerner, G. H. (2003). Selecting next speaker: The context-sensitive operation of a context-free organization. Language in Society, 32(2), 177–201. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004740450332202X

- Lerner, G. H., & Takagi, T. (1999). On the place of linguistic resources in the organization of talk-in-interaction: A co-investigation of English and Japanese grammatical practices. Journal of Pragmatics, 31(1), 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)00051-4

- Liberman, K. (2013). More studies in ethnomethodology. State University of New York Press.

- Mondada, L. (2019). Conventions for multimodal transcription (v. 5.0.1) [Unpublished manuscript]. https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription

- Ogden, R. (2020). Audibly not saying something with clicks. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 66–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1712960

- Oloff, F. (2017). “Genau” als redebeitragsinterne, responsive, sequenzschließende oder sequenzstrukturierende Bestätigungspartikel im Gespräch. In H. Blühdorn, A. Deppermann, H. Helmer, & T. Spranz-Fogasy (Eds.), Diskursmarker im Deutschen: Reflexionen und Analysen (pp. 207–232). Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.

- Rawls, J. (1955). Two concepts of rules. The Philosophical Review, 64(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/2182230

- Rossi, G. (2018). Composite social actions: The case of factual declaratives in everyday interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(4), 379–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1524562

- Sacks, H. (1973). On some puns: With some intimations. In R. W. Shuy (Ed.), Report of the twenty-third annual round table meeting on linguistics and language studies (pp. 135–144). Georgetown University Press.

- Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation (G. Jefferson, Ed.; Vol. 1). Blackwell.

- Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge University Press.

- Selting, M., Auer, P., Barth-Weingarten, D., Bergmann, J., Bergmann, P., Birkner, K., Couper-Kuhlen, E., Deppermann, A., Gilles, P., Günthner, S., Hartung, M., Kern, F., Mertzlufft, C., Meyer, C., Morek, M., Oberzaucher, F., Peters, J., Quasthoff, U. M., Schütte, W., & Uhmann, S. (2009). Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2: GAT2. Gesprächsforschung, 10, 353–402. http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2009/px-gat2.pdf

- Seuren, L. M., Huiskes, M., & Koole, T. (2016). Remembering and understanding with oh-prefaced yes/no declaratives in Dutch. Journal of Pragmatics, 104, 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.02.006

- Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (Eds.). (2013). The handbook of conversation analysis. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Stivers, T. (2005). Modified repeats: One method for asserting primary rights from second position. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 38(2), 131–158. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3802_1

- Stivers, T., & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing response. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 43(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903471258

- Svensson, H., & Tekin, B. S. (2021). Rules at play: Correcting projectable violations of who plays next. Human Studies, 44(4), 791–819. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-021-09591-6

- Wilkinson, S., & Kitzinger, C. (2006). Surprise as an interactional achievement: Reaction tokens in conversation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(2), 150–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250606900203

- Wilson, T. P. (1970). Normative and interpretive paradigms in sociology. In J. D. Douglas (Ed.), Understanding everyday life: Toward the reconstruction of sociological knowledge (pp. 57–79). Aldine.

- Zinken, J., Kaiser, J., Weidner, M., Mondada, L., Rossi, G., & Sorjonen, M.-L. (2021). Rule talk: Instructing proper play with impersonal deontic statements. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 660394. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.660394