ABSTRACT

Repair organization provides a powerful mechanism for handling problems of mutual understanding in natural conversation. Our study reviews past research on repair initiation and resolution practices involving embodied-visual practices, including eye gaze, facial expressions, hand gestures, and head and body movements. We charted details of theoretical background, methodology, and main findings for 31 studies. Embodiment was studied equally in connection with self- (SIR) and other-initiated repair (OIR); gaze and gestures were the most commonly studied embodied-visual practices. In OIR sequences, research has focused on upper body and gaze. In SIR sequences, more gestures were examined, but this may be specific to word search, which was predominant in SIR studies. In addition, embodied-visual practices can form gestalts independently from talk, and can occur early in the repair sequence, even pre-trouble source. Data were in Argentine Sign Language, Cha’palaa, Danish, English, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Turkish, and Yélî Dnye.

Introduction

In natural conversation, people regularly encounter problems in speaking, hearing, and understanding each other. These problems, known as trouble sources, are resolved with conversational repair practices, which are short and transient operations used by both speakers and the recipients of trouble (Schegloff et al., Citation1977). Repair is omnirelevant (Schegloff, Citation1979), in that trouble can occur at any time, among any participants, and in any language.

Speakers may self-initiate self-repair (SISR) on their own talk and recipients may other-initiate repair on the problematic talk of others, and there is a general preference for self-repair by the original speaker of the trouble source (Schegloff, Citation2000; Schegloff et al., Citation1977). With practices of self-initiated self-repairs, speakers can repeat, add, replace, delete, or abandon something already said (as well as combinations of those), indicating the initiation with glottal closure, hesitation markers, pauses, or specific repair phrases or particles such as I mean in English or eiku in Finnish (Fox et al., Citation2010; Laakso & Sorjonen, Citation2010). Self-initiated self-repair can also be seen in word searches that are initiated by speakers who have trouble finding the next element in their speech (Schegloff et al., Citation1977). Other-initiated repair can be further specified as other-initiated self-repair (OISR) and other-initiated other-repair (OIOR), the latter being less preferred (Schegloff, Citation2000). Other-initiations can be open, targeting the prior turn as a whole, or they can be more specified questions, questioning repetitions, or offers of candidate understanding (Drew, Citation1997; Kendrick, Citation2015a; Schegloff et al., Citation1977). Repair practices of self-initiated repair (SIR) and other-initiated repair (OIR) have been described as having a threefold structure of trouble source, repair initiation, and repair resolution (Schegloff et al., Citation1977). Self- and other-initiated self-repairs are the main types of repair that conversation analysis (CA) studies have shown to occur typically in everyday interaction universally (Dingemanse et al., Citation2015; Schegloff, Citation2006).

Although the emphasis of previous research in CA has been on spoken repair practices, the importance of embodied-visual practices has been acknowledged ever since the use of videorecorded data began, and it is continuously growing (Bolden, Citation2011; Bolden et al., Citation2022; Fox, Citation1999; Goodwin, Citation1979, Citation1981, Citation2003; Mondada, Citation2019). For example, Goodwin’s early studies demonstrated the significance of embodied-visual practices in the environment of self-repair among participants with symmetric competencies (Goodwin, Citation1979, Citation1981). Goodwin demonstrated that if speakers find themselves speaking to a nongazing recipient, self-repair practices such as restarts can be used to solicit gaze.

In work on asymmetric interactions, several studies have noted the use of embodied-visual practices in repair (e.g., Girard-Groeber, Citation2020; Goodwin, Citation2003; Laakso, Citation1997; Tykkyläinen, Citation2010). The sequentially unfolding use of, for example, gaze shifts toward or away from the recipient, frowning or lifting eyebrows, and pointing hand gestures are seen as “economical demonstrations” of trouble (Goodwin, Citation1981, p. 112), which can be done simultaneously with verbal turns. Moreover, embodied-visual practices are seen as resources used to maintain intersubjectivity when problems in speaking occur (Goodwin, Citation2003; Klippi, Citation2003; Laakso, Citation2003).

Although a great deal of work has been done on the verbal practices of repair, and the findings of that body of research have been summarized in a variety of places (e.g., Hayashi et al., Citation2013), the research on embodied-visual practices involved in repair remains scattered. It is the goal of the present review to summarize that research, as well as to integrate it with what is known regarding verbal practices of repair. To this end, we applied the increasingly common scoping review methodology, which is suitable for identifying the size and scope of the existing literature on a particular research area (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The purpose of a scoping review is to provide an overview of key concepts, gaps in the research, and types and sources of evidence, which researchers can then use to identify areas for future research. Scoping reviews share similarities with systematic reviews, inasmuch as both types of review are conducted in a systematic, transparent manner so that the search terms, as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria, are kept constant and reported in detail for replication. However, whereas the systematic review is best suited to experimental research designs, the scoping review is better suited for synthesizing results of qualitative and mixed methods approaches (Munn et al., Citation2018), both of which are used in research studying conversation. We discuss the findings as we present them to synthesize and highlight the embodied-visual phenomena found.

The specific research questions were these:

What kind of research has been done on embodied-visual practices in connection with repair phenomena?

What are the data (sample size, details, and sampling procedure) studied?

Which methodology has been used, and how have the data been transcribed and analyzed?

What are the key findings?

Which embodied-visual practices have been studied in connection with repair and in which ways do they relate to SIR and OIR phenomena?

What is the temporal organization of embodied-visual practices in relation to the verbal phases of repair?

In this study we report on our findings from the scoping review, which yielded 31 relevant journal articles. We now turn to present the methods employed for the review.

Methods

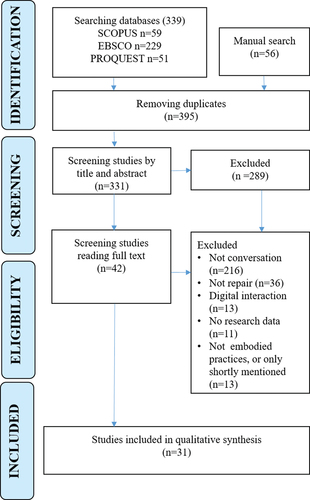

The current scoping review follows the updated guidelines of Peters and colleagues (Peters et al., Citation2020) and uses the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (Tricco et al., Citation2018). Following these guidelines, we formed our research questions; identified and then selected the relevant studies according to our inclusion criteria (); charted the data; and collated, summarized, and reported the results. In line with the scoping review methodology, we also assessed the quality of included research designs. We chose to use the hierarchy of evidence for qualitative research by Daly and colleagues (Daly et al., Citation2007), because it is suitable for assessing studies based on conversational data and conversation analysis, which often combine qualitative and mixed methods. According to Daly, generalizable studies represent the highest level of evidence (Level 1), in which data sampling is guided by theory, analysis is comprehensive, and the sample size is large enough for generalizing results to the general population. Conceptual studies represent the second highest level (Level 2), in which theoretical concepts guide sample selection, based on analysis of literature, but analysis may be less generalizable due to limited sample size. In descriptive studies (Level 3), the sample is selected to illustrate practical rather than theoretical issues, and the analysis records a range of illustrative quotes, including themes from the accounts of many, most, or some study participants. In single case studies (Level 4), rich data of one person are examined in depth. We found that the hierarchy of evidence suggested by Daly was applicable even for conversation analytic studies, which are based on accumulating research that builds solid theory of the basic structures of interaction, including repair phenomena, in spite of the fact that such studies do not necessarily set out to explore theoretical concepts, and sample size is typically not treated as relevant.

According to preliminary searches and reviewing content, we identified the databases Proquest, EBSCO, and Scopus as having the most relevant publications on the topic. Furthermore, we found relevant literature by hand picking from reference lists of the articles, as well as related book chaptersFootnote1 and doctoral dissertations,Footnote2 and the selection was guided with the same inclusion criteria as for the articles identified with database searches. The first author performed the search (February 17, 2022, and updated on May 8, 2023), limiting the selections to peer-reviewed journal articles and articles written in English, Finnish, German, Swedish, and Dutch/Flemish. Date of publication was not specified. Due to the centrality of the terms “conversation” and “repair” (), those terms were required to appear in the title, whereas terms related to classes of “embodied” and “body” () were required to appear in the abstract.

Table 1. Search Terms Used in the Database Search.

Literature search

The database searches resulted in 339 citations (), which were combined with 56 hand-picked items. After removing duplicates, we were left with 331 journal articles for screening titles and abstracts. A total of 216 citations were excluded as being totally irrelevant or other than conversational spoken material, 36 were not repair, and 13 were digital interaction. Eleven articles did not report research data. After screening titles and abstracts, we had 42 published peer-reviewed journal articles that studied both repair and embodied-visual practices. However, reading the full text revealed that in 13 articles, embodied-visual practices were only briefly mentioned in the introduction or reported in transcripts, but no findings regarding embodied repair practices were presented in detail. Subsequently, 31 papers were included as data. A flow-chart illustrating our process is given as .

The first and second authors screened titles and abstracts for eligibility according to criteria agreed upon by all authors. Eligibility criteria were these: The study had to be peer reviewed and published in an academic journal; its topic of study had to be repair in human face-to-face conversation (not online or digital forms of interaction); and it had to report findings on embodied-visual practices (hand and facial gestures, body posture and movements, or eye gaze). Because the publication and evaluation process of dissertations differs around the world, we restricted the current scoping review to published journal articles. However, given the importance of book chapters and edited volumes as well as dissertations to the field, we provide a summary of these as footnotes.

All authors performed the full-text screening of the 31 selected articles so that each article was reviewed by at least two authors, and challenges were resolved in discussion. The data abstraction form was first piloted on three included articles, and it was modified as required based on feedback from the authors. Final data charting was done for reference details, aims and research question(s), methodology (CA or other), participants (number, age), language, asymmetrical or symmetrical competence, data, conversational setting, amount of data, repair types (self- or other-initiated), embodied-visuals reported, key findings/results, key findings of embodied-visuals, implications, and other (results in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Results

We present the results of the review in line with the research questions. In addition to summarizing the results and presenting the data in table format (Tables S2 and S3), we included narrative commentary to highlight the most prominent findings.

Description of the studies: Size and scope of the data and methodologies used

As we examined the 31 studies identified by our search process, we first looked at the type of data and methodology used (see Table S2 for details). Regarding participants, 28 studies included adults and three included children (Radford, Citation2009; Rasmussen, Citation2014; Wiklund, Citation2016). Eighteen of the studies had participants who spoke English, either as a native or second language, and 15 studies had participants with native languages other than English. In addition, besides spoken languages, two of the studies had participants who used sign language (Floyd et al., Citation2016; Manrique, Citation2016). Approximately two-thirds of the studies could be considered single or multi-case studies with fewer than 10 participants. However, this was subject to interpretation, because 10 articles did not report the exact number of participants but instead described the corpus they used (see Table S2). In the rest, the number of participants was more than 10 (variation between studies 10–106 participants). In two-thirds (21/31) of the studies some of the data characteristics (e.g., number of participants, gender, age, or amount of data) were not described.

Data in all studies were video-recorded dyadic (19) or group (17) conversations, some studying both. Twenty-three of the studies reported the total amount of data in hours and 12 gave specific information regarding the quantity of repair phenomena (e.g., number of word search segments) examined. Conversations were collected more often in mundane (19) than in institutional (12) contexts. Furthermore, two-thirds (17/31) of the studies examined conversations between participants with asymmetrical competencies. The causes for asymmetries in competence were mostly of medical origin: aphasia (6/17), hearing loss (5/17), developmental language disorder (1/17), and autism spectrum disorder (1/17). Besides medical causes, asymmetry was connected to the use of a second language (L2) in four studies (Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022; Mortensen, Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Seo & Koshik, Citation2010).

All studies used CA methodology (Sacks, Citation1992; Sacks et al., Citation1978), and the data were transcribed according to CA conventions (Atkinson & Heritage, Citation1984; Jefferson, Citation1984, Citation2004). The transcription of embodied phenomena varied, although seven studies transcribed gaze according to Goodwin’s (Citation1981: viii) conventions. Most studies presented embodied-visuals in the transcripts using verbal descriptions of embodied behavior in double brackets or italics. In addition, line drawings, or still pictures from the videos, were used to illustrate the visual displays of embodied phenomena. In four more recent studies (Ekberg et al., Citation2017; Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022; Mortensen, Citation2016; Rossi, Citation2020) multimodal transcriptions were done according to Mondada (Citation2014, Citation2018). In Auer and Zima (Citation2021), conversation was transcribed according to Selting et al.’s (Citation2009) GAT2 convention, with gaze analyzed with eye tracking instead of observation. In one study, researchers also performed turn duration calculations with ELAN (Kendrick, Citation2015a).

When we assessed the included research according to the hierarchy (Levels 1–4) of evidence-for-practice in qualitative research–study types and levels (Daly et al., Citation2007), we concluded that the studies forming our dataset represented Levels 2 (conceptual studies), 3 (descriptive studies), and 4 (single case studies). None of the research represented the highest category of Level 1 (generalizable study). However, as a strength, all the samples of the reviewed studies were guided by a theoretical framework (CA). Eight of the studies were conceptual (Auer & Zima, Citation2021; Duran et al., Citation2022; Ekberg et al., Citation2017; Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022; Laakso, Citation2014, Citation2015; Manrique, Citation2016; Seo & Koshik, Citation2010). Ten were descriptive (Floyd et al., Citation2016; Greer, Citation2013; Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1986; Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Kendrick, Citation2015a; Klippi, Citation2015; Laakso & Klippi, Citation1999; Mortensen, Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Pajo, Citation2013), and the remaining 21 either were single case studies or the information was not available.

Key findings: Which embodied-visual practices have been studied in connection with repair?

We then reviewed the articles in detail to find out which embodied-visuals were studied in connection to SIR and OIR and what the key findings were in that regard (Table S3). In the 31 articles reviewed, SIR was the topic of investigation in half of the studies. Furthermore, of the 15 SIR studies, 12 analyzed embodied behavior in connection with word searching. OIR was the focus of the study in 16 articles, of which two also examined self-initiated repair. Next, we will summarize the key results reported in the 31 studies related to SIR and OIR. Most commonly the studies explored the interactional functions of several embodied-visuals simultaneously. Embodied-visuals and their functions in interaction are presented here in order from most to least studied.

Eye gaze

Eye gaze was analyzed in almost all (27/31) studies; gaze was found to be used to monitor collaboration or display independent problem-solving in interaction. In 11 of the 27 cases, gaze was found to be connected to self-initiated repair and, more specifically, to word searching (Table S3). The earliest of the studies on gaze is the classic, influential study by Goodwin and Goodwin (Citation1986), who found that speakers shift their gaze away from their recipients when they start searching for a word (see ). Gaze withdrawal was also often accompanied by facial displays, such as “thinking face.” Goodwin and Goodwin (Citation1986) concluded that these embodied displays frame the search visually to the recipients as an ongoing activity.

Figure 2. Gaze shift (originally from M. H. Goodwin and Goodwin (Citation1986, p. 57). Line above speech refers to the speaker’s gaze toward the recipient, and commas refer to shifting gaze away from the recipient. Facial display of thinking face is marked above speech transcript.

The finding of averted gaze during word searching is repeated in other reviewed studies in both symmetric and asymmetric conversations (e.g., Greer, Citation2013; Laakso, Citation2015). However, several studies found that conversation partners with asymmetrical competencies deploy shifting gaze toward the recipient to invite the more competent recipient(s) to help in the search (Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Laakso, Citation2015; Laakso & Klippi, Citation1999). Invitation by gaze was also observed in conversations between participants with symmetrical competencies (Hayashi, Citation2003; see ). By shifting the averted gaze back to the recipient, the speaker makes relevant the active co-participation of the recipient, who then delivers a candidate to complete the search.

Figure 3. Invitation by gaze (Hayashi, Citation2003, pp. 115, 117; reprinted with permission from the copyright holder).

On the other hand, some reviewed studies showed that invitation with gaze does not always lead to recipient co-participation in word searching (Auer & Zima, Citation2021; Laakso, Citation2015). More precisely, Auer and Zima (Citation2021) found that eye gaze is more effective in inviting co-participation in certain activities (co-telling) and with certain spatial arrangements of the participants (side-by-side). Although being complex and context-dependent, eye gaze nevertheless appears as an embodied display that is relevant for self-initiated word searching activity.

Besides SIR/word searching, in about one-third (12/31) of the studies eye gaze was explored in connection with OIR. Similar to the findings with word searches, Pajo and Klippi (Citation2013) found that recipients with hearing loss shifted their gaze toward the speaker to elicit repair, the gaze shift thus functioning as an embodied form of other-initiation of repair (see ).

Figure 4. Timing of gaze. The timing of recipient (KER) gaze is marked below the speaker’s utterance, and dots refer to shifting gaze toward the speaker (originally from Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013, p. 170, reprinted with the permission of the copyright holder).

Here the recipient with hearing loss shifts gaze to the speaker after the word eno “uncle,” simultaneously displaying difficulty in hearing by frowning and leaning toward the speaker. In response to the embodied displays, which the authors call non-vocal action, the speaker repeats and adds a specification, the name Tapani, to specify who the uncle is that is being talked about. In OIR, gaze was often accompanied with other non-vocal actions that included leaning forward, frowning facial display, and turning one ear toward the speaker (Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013). Similarly, Seo and Koshik (Citation2010) observed gaze combined with head tilts and pokes, and upper body movement toward the speaker functioning as open-class OIR corresponding to verbal hm? or “what?” In both studies non-vocal OIRs functioned as a prompt to the speaker to self-repair.

The reviewed studies also showed that lack of mutual gaze in itself can be the source of difficulty that results in OIR, especially when one of the participants has a hearing loss (e.g., Ekberg et al., Citation2017; Skelt, Citation2010). Moreover, Wiklund (Citation2016) found that lack of mutual gaze was the most common reason for conversational breakdown leading to OIR in group conversations of teenage individuals with autism spectrum condition (ASC, referred to as autism spectrum disorder in the original article). In symmetric conversation, lack of mutual gaze during a trouble-source turn led to the recipient initiating (other-initiation) repair with the open-class repair initiator in German, bitte (appr. “pardon”; see Egbert, Citation1996). Gaze thus provides an embodied display that essentially supports intersubjective understanding in interaction.

Hand gestures

Hand gestures were also commonly analyzed in studies included in the review (22/31), and they were used to specify the referents by pointing or depicting. Thirteen of those studies analyzed hand gestures connected to SIR (Table S2) and nine to OIR (Table S2). Pointing gestures were studied in five studies on SIR (e.g., Duran et al., Citation2022; Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Klippi, Citation2014; Laakso, Citation2015; Wiklund, Citation2016); all focused on conversations among individuals with asymmetrical competencies (aphasia, ASC, and L2). In these studies, pointing was reported to co-occur specifically with word searches, providing information on the item sought or clarifying the missing referent (Duran et al., Citation2022; Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Klippi, Citation2014; Laakso, Citation2015; Wiklund, Citation2016). Pointing at or touching the recipient was also used with gazing to invite the recipient’s collaborative participation in word searches (e.g., Klippi, Citation2014; Skogmyr & Doehler, Citation2022). Depictive hand gestures that visuo-spatially represent relevant objects and events were studied in four SIR studies, most commonly in word searches; these gestures illustrate the item sought, in both asymmetric (Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Laakso & Klippi, Citation1999) and symmetric conversations (Hayashi, Citation2003; Skogmyr & Doehler, Citation2022; Wu, Citation2022). These gestures were variously referred to as iconic, depictive, descriptive, and illustrative in the reviewed studies. In conversations between participants with asymmetric competencies, pointing at referents and depictive hand gestures were often verbalized by the recipients of the word search (e.g., Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Laakso, Citation2015). In self-initiated word searching activity, hand gestures offered the recipient a visual display of the item sought, thus completing the search non-vocally.

Depictive hand gestures were also examined in OIR studies (Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022; Mortensen, Citation2016; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013). Such gestures were used to initiate repair on the other’s trouble source, both as open-class initiators and as candidate understandings. Mortensen (Citation2016) showed that cupping the hand behind the ear was used to indicate generally a trouble in hearing, and to function as an open-class OIR. Similar to leaning toward and turning the ear toward the speaker (Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013), the cupping hand gesture was typically used to OIR on a prior turn, without accompanying speech. Also Jokipohja and Lilja (Citation2022) found that depictive hand gestures were used in L2 interaction independently, without speech. In their OIR study, depictive hand gestures that showed how something was done (e.g., using utensils) functioned as candidate understandings of prior talk and were offered for confirmation to the speaker of the trouble source. Furthermore, in the context of concrete tasks (farming and cooking) depictive gestures had features that resembled pointing gestures in that they were interpreted in relation to the material resources in the physical environment (Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022). Hand gestures depicting actions and events were also used by participants with aphasia, and they were not being used to initiate repair (e.g., Wilkinson et al., Citation2010). These embodied enactments were then interpreted by the recipients who offered their candidate understanding as OIR. In sum, the reviewed studies showed that, although recipients interpreted pointing and depictive hand gestures, the gestures got their specific meaning in the activity and material context in which they were used.

Facial displays

Facial displays (also called facial actions, frowns, eyebrow movement, facial gestures, and non-manual signs) were studied in 16 of the 31 studies included in the review (Tables S2 and S3), and they were used to express speakers’ emotion or attitude toward the trouble source. They were studied in connection both with SIR (8/16) and with OIR (8/16). However, only eight studies (Duran et al., Citation2022; Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1986; Floyd et al., Citation2016; Laakso, Citation2014; Levinson, Citation2015; Manrique, Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Pajo, Citation2013; Rossi, Citation2020) reported specific findings. Regarding SIR, Goodwin and Goodwin (Citation1986) described a “thinking face” along with averted gaze during word searches. In more recent studies, facial affective displays were found to be resources for persons with aphasia (Laakso, Citation2014) or L2 speakers in a classroom (Duran et al., Citation2022) to display awareness of their difficulty in word searching. In OIR, facial expressions were mainly observed as part of a “trouble posture” (Pajo, Citation2013) or holds (Floyd et al., Citation2016; Manrique, Citation2016), but also as marking the beginning of repetition turns (Rossi, Citation2020). Interestingly, facial signals may be culturally conventionalized (e.g., affirmative blink and eye brow raise; see Levinson, Citation2015). They were also observed in combination with head and body movements (Oloff, Citation2018; Rossi, Citation2020).

Body and head movement/posture

Body posture and movement were studied in nine of the 31 reviewed studies (Tables S2 and S3), and mainly in connection with OIR to express trouble. Of those studies that examined body posture, five reported static body (also called hold, freeze, immobility, and trouble posture) as a general indication of trouble in conversation (Floyd et al., Citation2016; Manrique, Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013; Rasmussen, Citation2014). Holding the body static—that is, freezing any movement—was considered an implicit way to indicate problems of understanding if produced by the recipient while looking directly at the speaker of the trouble source (Manrique, Citation2016). Notably, even a nonmoving hand was found meaningful in sign language interaction when it was related to a hold, or static body posture, which is held until the trouble is resolved (Floyd et al., Citation2016). In sign language interaction, holds were more frequent in OIR than during spoken language interaction (Floyd et al., Citation2016). The reviewed studies suggested that body movements such as leaning forward or reorienting the body were used as a means to OIR, especially in conversations with people with communication challenges (e.g., Floyd et al., Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Rasmussen, Citation2014). The studies revealed that, as soon as the trouble is resolved, the body and head movement or posture is released (e.g., Seo & Koshik, Citation2010; Skogmyr & Doehler, Citation2022).

Head movement was reported in a total of 16/31 studies (Table S2). In six of the studies, they were examined with hand gestures. Head tilt and poke were found to indicate trouble and OIR (Seo & Koshik, Citation2010), as did reorientation of the head (Kendrick, Citation2015a) and upward movement of the head (Oloff, Citation2018). Hearing-impaired participants used a combination of raised eyebrows and an upward movement of the head or forward movement of the torso as a specific indication of trouble in hearing (Oloff, Citation2018). In the reviewed studies, head and body movements and freezes functioned as non-vocal open-class repair initiators to which the speakers of the trouble source responded with repair.

Embodied-visual practices and the temporal organization of repair

Finally, we examined the studies to understand their findings relating to how the embodied-visual practices were used in different phases (trouble source, initiation, and resolution) of repair sequence. In the studies reviewed, the timing of embodied-visual practices with respect to verbal SIR or OIR was not usually studied systematically. However, we made some observations and drew some conclusions regarding the temporal organization of embodied displays and the verbal components of the repair sequences.

According to the reviewed literature, in SIR embodied actions could foreshadow upcoming difficulties in asymmetrical contexts. In Laakso (Citation2014), the speaker shifts their body away from the recipient at the very beginning of the problematic turn, before the trouble source per se has been produced. Also in symmetric contexts, Goodwin and Goodwin (Citation1986) found that in word searching the thinking facial expression and gaze aversion starts before the talk is actually interrupted, signaling early on the upcoming verbal search activity. Similarly, Skogmyr and Doehler (Citation2022) found gesture hold and gaze aversion at the onset of word search. During the search, gaze aversion and thinking face displayed non-vocally that the speaker was still involved in producing a turn, even though the progressivity of that turn was temporarily delayed (Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1986; see also Hayashi, Citation2003). In word search studies, pointing and depictive hand gestures also functioned as a means of repair resolution. Pointing at or illustrating the missing referent was verbalized by the co-participants, resulting in self-initiated other-repair (e.g., Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Wu, Citation2022). If the self-initiated gestural word search was resolved by self-repair of the speaker, the speaker usually repeated the initial gesture (Wu, Citation2022). Gestural hold was found to mark transition from search process to resolution (Skogmyr & Doehler, Citation2022). Furthermore, withdrawing gaze was used by participants with hearing loss to close repair sequences in which severe problems of understanding had arisen (Skelt, Citation2007).

In OIR, recipients with hearing loss produced embodied OIR even during the speaker’s trouble source turn, without waiting to produce a verbal OIR in the next turn (Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013). In a similar vein, the findings of Oloff (Citation2018) suggest that embodied-visuals may precede verbal OIR initiations in multilingual work environments. Moreover, Kendrick (Citation2015a)—a quantitative analysis of the timing of OIR among symmetric participants—revealed that embodied displays can precede verbal OIRs. Furthermore, Jokipohja and Lilja (Citation2022) found that depictive gestures in OIR were timed to occur early. In summary, these data suggest that embodied-visual practices can be the first indication of trouble and repair, even before verbal SIR or OIR.

Embodied-visual practices were also found to accompany verbal OIRs. For example, several studies found that if other-initiations of repair were accompanied with leaning head and body toward the speaker, it was a display of hearing difficulty (Ekberg et al., Citation2017; Oloff, Citation2018). Furthermore, different kinds of embodied-visual practices may index different sources of trouble in connection with OIR (Oloff, Citation2018). For example, in L2 work settings depictive gestures accompanied verbal OIR in offers for candidate understanding (e.g., Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022). In addition, when a depictive cupping of the hand behind the ear co-occurred with the teacher’s verbal OIR, it seemed to initiate repair on the linguistic form of the student’s turn, thus having a different function than cupping without verbal initiator, which indicated a hearing problem (Mortensen, Citation2016).

Several studies found that a static body or gesture was held until after the resolution of OIR repair (e.g., Floyd et al., Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Seo & Koshik, Citation2010). If the recipient was a person with a hearing loss, repair resolution was monitored by gazing and leaning toward the speaker producing the repair, which was held until feedback of uptake was produced, in order to ensure speech perception (Ekberg et al., Citation2017; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013). We return to this finding in our discussion below.

Summary and discussion

The aims of the current review were to scope the existing published literature related to embodied-visual practices during conversational repair, and to form an overview of the data characteristics and findings. In the following, we provide a summary of our findings in line with the research questions.

Summary of the research: Size and scope of data and used methodologies

We identified 39 published journal articles, but after reading the full texts, 31 articles were identified that met our inclusion criteria, and these we reviewed in detail according to the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews in respect to data, results, and findings (Tables S2 and S3). Even though most studies were either single-case or multi-case studies, combining findings from each provides a good perspective on embodied-visual repair phenomena. The studies were mainly on adult conversation, and child data was scarce (only three studies), even if gestures are known to have an important role in language development (Goldin-Meadow, Citation2009, Citation2014). Otherwise, the data of the reviewed studies constituted a representative sample of dyadic and group interactions drawn both from institutional and mundane contexts. The data included interactions of participants with symmetric and asymmetric competencies, the latter being more frequent.

Methodology

In all of the studies included, CA was the main method of analysis, which was not surprising, as “repair” is a CA term and is a topic of interest primarily to scholars of CA. Despite the studies all being grounded in a CA approach, the transcription practices and terminology of embodied-visual practices in the studies varied, which may hinder comparing results from different studies. It is important, although challenging, in transcribing embodied actions to notate the place and duration of the action in relation to the verbal utterances and sequential progress. Mondada´s transcription system (Citation2014, Citation2018), which takes the temporal and sequential features into account, was still infrequently used in the studies reviewed. This is related to the fact that the system is fairly new. If temporally accurate transcription becomes more widely used in the future, it may offer a solution for more systematic examination of the temporal organization of embodied-visual practices across studies. In any case, transparent documentation of transcription is important.

Summary of the key findings

Our second aim was to provide a summary of the key findings, especially in respect to the ways embodied-visual practices are used to accomplish SIR and OIR, and what is known about the temporal organization of embodied-visual practices in relation to the verbal phases of repair.

Embodied-visual practices relate to SIR and OIR in complex ways

Eye gaze was the most studied embodied-visual practice as it was analyzed in nearly all the studies. The next most studied were hand gestures, reported in over half of the studies. Approximately half of the studies reported head movement as well as facial displays, but body posture and bodily movement were studied less, in about one-third of the studies. Both SIR and OIR studies were represented equally (half of the data on each), which gives a view to the embodied organization of repair from both the perspective of the speaker and the recipient of the trouble source. Despite the examination of both SIR and OIR, the scope of the studies on embodied-visual practices was rather narrow, as the SIR studies focused mostly on word searching and the OIR studies focused on open-class initiations. Somewhat surprisingly, two-thirds of the reviewed studies were about conversations between people with asymmetrical competency. Importantly, the results of the analysis in the reviewed studies revealed that embodied-visual practices were used in various repair activities, such as difficulty in hearing, in understanding, and in finding a word. In addition, embodied-visual practices played a part in activities that regulated assistance and displayed affirmation or reactions (e.g., surprise). We now discuss in more detail how the embodied-visual practices were connected to repair.

We found that embodied-visual practices relate to SIR and OIR in complex ways. First and foremost, the review shows that eye gaze is at the core of building mutual understanding during all repair activities. In particular, gaze was used to regulate interaction between the participants. The speaker’s gaze away from or toward the recipient was analyzed in all but one of the studies on SIR. This is not surprising, as gaze was found to be relevant even in the first CA studies of embodied-visual practices (Goodwin, Citation1981; M. H. Goodwin, Citation1980), which also presented a gaze transcription system. Although gaze is an important resource in repair sequences, the reviewed research suggests that there are some differences between gaze use in SIR and OIR. In SIR, gaze is used to regulate co-participation as speaker’s gaze aversion indicates an attempt to manage the trouble without help, whereas gaze shifts to the recipient invite assistance (Auer & Zima, Citation2021; Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1986; Hayashi, Citation2003; Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Laakso, Citation2015; Skogmyr & Doehler, Citation2022). These interactional uses of gaze for inviting recipient collaboration are in line with the observations that speakers use gaze to signal the relevance of a response from the recipient (e.g., Stivers & Rossano, Citation2010). On the other hand, in OIR the recipient’s gaze toward the speaker indicates more consequential trouble in hearing or understanding, often as part of an embodied hold (Seo & Koshik, Citation2010; Pajo, Citation2013; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013; Manrique, Citation2016; Floyd et al., Citation2016; Oloff, Citation2018; Skogmyr & Doehler, Citation2022). To summarize, in both SIR and OIR, gaze toward the other participant invites some kind of help, either in the form of participating in a word search or in the form of repeating what was just said.

For asymmetric competencies, embodied-visual practices such as eye gaze are used as a means to compensate. For example, for a person with aphasia, embodied resources may be still relatively intact in comparison to their verbal skills and thus may offer a means to proceed in the conversation, or demonstrate the need for repair. Therefore, embodied-visual practices assist the person with aphasia in gaining social competence (Laakso, Citation2014; Wilkinson et al., Citation2010). Also, if the co-participant has a hearing loss, the partners continuously monitor the availability of co-participants’ gaze, and their talk is shaped according to this availability (Skelt, Citation2010). Similarly, Seo and Koshik (Citation2010) reported that, in a classroom context of second-language learners, the participants constantly gaze monitor each other for evidence of confusion, which can manifest in further embodied displays. In contrast, a participant with autism spectrum condition may avoid direct eye contact (Wiklund, Citation2016), which may be related to avoiding hyperarousal and stress induced by direct eye contact (Stuart et al., Citation2022). Thus, eye gaze is not present in all asymmetric interactions.

In addition to gaze, in SIR sequences hand gestures are vital resources, although this may be word-search specific, given the strong focus of SIR studies on word searches. In OIR sequences the embodied displays focus on upper body, head, and facial expressions. Furthermore, leaning toward the speaker is specific for achieving better hearing of the speaker. A specific set of embodied OIR initiators—face (especially eye gaze and eyebrows), head, hands—seems to be found in all the languages that have been studied so far, which suggests that these practices may be grounded in some of the most basic human interactional resources.

In the studies reviewed, both SIR and OIR were accompanied by deictic (pointing; Kendrick, Citation2015a; Klippi, Citation2014; Laakso, Citation2015; Radford, Citation2009) and depictive (iconic, enactment; Wilkinson et al., Citation2010; Helasvuo et al., Citation2004; Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022) gestures. Pointing was not merely declarative, as in drawing attention toward something; rather, in the instances when it was used to aid in a word search, it had the semantic purpose of indicating the referent of the missing word.

Although some embodied-visual practices may be accurate and easy to understand (e.g., depictive gestures; Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022), some cause prolonged episodes of repair. In particular, in conversations with a participant with severe aphasia, the co-participants regularly have difficulties in understanding a turn constructed with few words and several embodied resources (Wilkinson et al., Citation2010). Thus, the co-participant is not only a conversational partner but also needs to be an interpreter (Klippi, Citation2014). In summary, as the asymmetry between the participants increases, for example, due to more severe aphasia or hearing loss, the use of embodied-visual practices also increases, as does the joint effort to concentrate and convey a message by both participants (Klippi, Citation2014; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013).

Embodied-visual practices take place early in repair sequence

Although verbal practices of repair have been discussed in the wider literature in terms of three phases of repair (trouble source, initiation, and repair/resolution), an examination of research on embodied-visual practices of repair reveals a more complex and dynamic temporal organization. As we examined the temporal placement of embodied-visual practices, we found that they were timed early both in SIR and OIR sequences. In SIR the embodied-visuals can occur pre-trouble source—that is, even before the speaker has verbally indicated any trouble (Goodwin & Goodwin, Citation1986). From there on, the embodied-visual practices can be held or slightly shifted during the trouble source phase, when the trouble possibly becomes overt verbally (Laakso, Citation2014; Skogmyr & Doehler, Citation2022).

Moreover, in OIR the embodied-visual practices indicating the recipient’s trouble can be initiated during the speaker’s trouble source turn (Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013), early in turn transition relevance place (Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022), during a gap between turns (Kendrick, Citation2015a), or during verbal initiation of trouble (Floyd et al., Citation2016). After the embodied display is initiated, it is typically held until the repair is resolved (Floyd et al., Citation2016; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013). Temporally early embodied-visual OIR may reflect the preference for self-repair (Schegloff et al., Citation1977) because, as the recipient displays problems in hearing or understanding during the speaker’s turn, it offers the speaker a possibility to self-repair before a verbal OIR is produced. Early embodied OIR practices thus support the general preference for self-repair noted in Schegloff et al. (Citation1977).

Theoretical relevance of the findings

Our synthesis supports the view that conversational repair is built via deployment of embodied-visual and linguistic practices to reach mutual understanding, and that it is dynamic similarly to other kinds of conversational practices (e.g., turn-taking; De Jaegher et al., Citation2016; Goodwin, Citation2000). In face-to-face interaction, the use of embodied-visual resources during repair sequences highlights the occurrence of the trouble both by the speaker and by the recipient, and assists in making it momentarily a focal activity of the interaction. It seems also that in repair, talk and embodied displays work together as “packages” to accomplish particular interactional work (cf. Keevallik, Citation2013; Kärkkäinen & Thompson, Citation2018).

Our review has also revealed that embodied-visual practices can sometimes work somewhat independently of verbal practices for initiating repair; in particular, it has been noted that OIR can be initiated early with embodied-visual practices. In contrast to verbal displays of OIR, embodied-visual OIR practices may not be delayed at all, but may rather be timed to occur early (e.g., Oloff, Citation2018; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013). This is in line with previous work suggesting that embodied responses to action may start even while the action it responds to is still being produced (Deppermann et al., Citation2021; Mondada, Citation2021), and that early reaction is relevant also for actions related to repair (Deppermann & Schmidt, Citation2021). Nonetheless, as nonverbal activity, embodied OIR practices still allow a space for the trouble-source speaker to self-repair before the recipient produces a verbal repair initiation (e.g., Oloff, Citation2018; Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013), thus following the general preference for self-repair. In fact, it may be that the practice of delaying the verbal expression of OIR is (at least in certain circumstances is) facilitated by early initiation through embodied means (cf., Kendrick, Citation2015b, pp. 8–11). If this possibility is the case, it deeply enriches our understanding of repair and of the relationships between verbal and embodied-visual practices for achieving intersubjectivity.

In addition, early timing of embodied-visual practices suggests several conclusions, noted by some of the studies in our review. First, embodied-visual practices have a different interactional status than do verbal practices, in being less “on record” than verbal practices. Second, the fact that they are in a different (and silent) modality than the spoken languages (but see Manrique, Citation2016, on sign languages) affords production simultaneous with verbal turns by the other speaker, without being considered interruptive. And third, it appears that trouble—both by speaker and recipient—can be flagged early, and this fact can only be observed if one looks at embodied-visual practices (see Deppermann et al., Citation2021, for studies on early responses, including embodied-visual responses).

It also bears mentioning that multimodal practices for repair tend to be produced in clusters (Kärkkäinen & Thompson, Citation2018; Keevallik, Citation2013; Mondada, Citation2018, Citation2021; Stukenbrock, Citation2018)—that is, more than one body part is involved. For example, cupping the ear (hand and head) may be accompanied by leaning in (torso) and frowning (face; Mortensen, Citation2016). The theoretical implications of this clustering have yet to be explored fully, but we can suggest that, when it comes to the body, at least in the domain of repair, the constraints on meaning-making semiotic resources are relaxed, and so there may be no limit on the semiotic resources used (e.g., Kress, Citation2009; see also Mondada, Citation2021). In fact, it seems that the whole upper body is typically engaged. Whereas in the verbal stream only one word can be produced at a time, in the simultaneous environment of the visually-available body, all resources are available for use at the same time.

According to the reviewed studies, an important feature in embodied-visual practices is that they are context-sensitive. These contextual differences are important to consider (Streeck et al., Citation2011) because they make embodied actions open to various interpretations according to the conversational context in which they occur. For example, Oloff (Citation2018) examined an international customs office and studied the practices through which an embodied indication of trouble is interpreted as a language problem instead of a hearing problem. Furthermore, different embodied-visual practices are used conjointly, and thus form familiar gestalts. As an example, persons with hearing difficulties tend to shift their gaze and lean toward the speaker (Ekberg et al., Citation2017). When these familiar gestalts are recurrently placed in similar sequential position or phases of repair sequence, it further assists in their interpretation (see Jokipohja & Lilja, Citation2022, on how depictive gestures acquire their meaning).

Several articles in our data stated that their findings on embodied practices might not be fully generalized or transferrable to other types of settings. However, this scoping review reveals that, indeed, similar embodied-visual practices during SIR or OIR repair sequences are found in various symmetrical and asymmetrical interactions.

Moreover, in analyzing interactions between participants with asymmetric speaking/hearing competencies, we should not make quick assumptions that, for example, hearing loss or language competency is always relevant in all repair sequences. It is important to carefully analyze the participants’ own orientation in every local repair sequence. However, in the studies we reviewed, embodied-visual practices seemed to be more prominent and occur more frequently in asymmetric interactions. For example, the rate of OIR-sequences can increase in severe hearing loss (Lind et al., Citation2004; Pajo, Citation2013). Moreover, word searches can be long and explicitly marked in conversations between individuals with aphasia and speech and language therapists (Laakso, Citation2015). In addition, the embodied gestalt can be more overt, including several features in comparison to symmetrical interaction (Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013; Wilkinson et al., Citation2010).

Limitations

The following limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting the results of the current review. During preliminary searches, it became evident that the database search did not identify many relevant published articles. This resulted in the addition of a large number of handpicked journal articles, which lowers the replicability of the review. However, after consulting the local informatician, it was concluded that this was most likely due to unsystematic indexing of the journals that publish relevant research, and thus identifying relevant research based on the previous knowledge of the authors was justified. Finally, the review is based on a rather small number of studies (31), and therefore the results should be generalized with caution.

Gaps in the literature and directions for future research

In addition to interesting findings, our review identified gaps in the previous research, which are useful to consider when planning future studies. In order to fully understand the functions of embodied-visual practices, more research is needed in both SIR and OIR. There was a gap of research in embodied-visual practices in connection with types of self-initiated self-repairs other than word search (e.g., adding, replacing, abandoning), and it is unclear whether embodied-visual practices may be specific to word search. Similarly, more research on other-than-open-class initiations is needed to fully understand the role of embodied repair practices during OIR. The great majority of the research in the current review was on adult conversation, and only little is known about the embodied repair practices in children. It would be especially useful to have data on children with symmetrical competencies, as this could reveal important information regarding the development of embodied communicative competence. Furthermore, although the papers revealed some interesting insights about the timing of embodied-visual practices, only a few studies reported the timings in detail. In the future, more uniform transcription practices and reporting of exact timing of embodied-visual practices in relation to verbal repair would further increase understanding of their occurrence. This applies to all phases of repair sequences, but we note that repair resolution in particular lacked research. More research is also needed to specifically compare the use of embodied resources in symmetric and asymmetric interaction to resolve the issue of whether embodied behavior is more frequently used in linguistically asymmetric interaction than in symmetric interaction.

Conclusions

Our review highlights that, in addition to linguistic means, embodied-visual practices are important resources used both in SIR and OIR in conversation either alone or accompanied by a verbal turn. In the reviewed literature, gaze and hand gesture were the most common embodied-visual practices in repair. There were subtle differences in the use of embodied-visual practices during SIR and OIR, the former involving hand gestures more than the latter, which was reported to be more connected to movements of the upper body. However, the connection between SIR and hand movements may be affected by the fact that a majority of our studies of self-repair focused on word searches, which indicates a need for more research. We also observed that different embodied-visual practices are used conjointly and thus form gestalts that occur also independently from talk. Interestingly, our review revealed that embodied-visual practices may be the first indication of trouble, and may take place even pre-trouble source.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (83.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2023.2272528

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A search of book chapters and edited volumes revealed very similar topics. Seven articles were identified as fitting the criteria and, as with the other studies reviewed here, they focused on word searches and OIR. Within word searches, there were several studies that noted iconic gestures and pointing in suggesting the referent (Gullberg, Citation2011; Klippi & Ahopalo, Citation2008; Radford, Citation2020). One study, Gullberg (Citation2011), also noted the use of repeated circular hand motions to index delays in progressivity during word searches. In turns initiating repair on the trouble source turn of another, iconic gestures and pointing were also found, as were various facial expressions such as frowning and smiling (Bloch & Saldert, Citation2020); squinting, raised eyebrows, and wrinkled nose (Girard-Groeber, Citation2020); and head shakes (Radford, Citation2020). Olsher 2008 was unique in focusing on the repair turn itself, after OIR. In this study on L2 learners of English, Olsher found that iconic gestures were used in repair turns to clarify the referent that was the trouble source in the trouble source turn.

2 We identified nine relevant dissertations on the topic of embodied practices for initiating repair. On further reading, four of those were found to not discuss repair and the body. We thus focused on the remaining five dissertations (Binti, Citation2017; Kim, Citation2004; Kunitz, Citation2013; Matsumoto, Citation2013; Sert, Citation2011). Although we limited our review to published journal articles and did not explore these dissertations in depth, we wanted to note a few important contributions of these studies. First, a few of them focused on pointing and other manual gestures for clarifying a referent that had been the source of trouble (including Kim, Citation2004; Matsumoto, Citation2013). Because many of the dissertations examined institutional talk, especially on non-native speakers of the language under study, it is perhaps not surprising that referent identification is a major task for the participants. Second, at least one dissertation focused on word searches (Binti, Citation2017), which is a common topic in our review. Third, one of the dissertations (Matsumoto, Citation2013) noted an embodied practice we have not seen in our other studies, which is the Other in OIR stepping closer to the speaker. The practice of stepping closer could be similar functionally to bringing the head closer in a head poke (Seo & Koshik, Citation2010) or to turning the ear toward the speaker (Pajo & Klippi, Citation2013), bringing the recipient perceptually closer to the speaker of the trouble source.

References

- Atkinson, J. M., & Heritage, J. (Eds.). (1984). Structures of social action. Cambridge University Press.

- Auer, P., & Zima, E. (2021). On word searches, gaze, and co-participation. Gesprächsforschung. Zeitschrift Zur Verbalen Interaktion, 22, 390–425. http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2021/ga-auer.pdf

- Binti, N. 2017. A multimodal conversation analytic study of word-searches in L2 interaction. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Newcastle:.

- Bloch, S., & Saldert, C. (2020). Person reference as a trouble source in dysarthric talk-in-interaction. In R. Wilkinson, J. Rae, & G. Rasmussen (Eds.), Atypical interaction: The impact of communicative impairments within everyday talk (pp. 347–372). Springer.

- Bolden, G. B. (2011). On the organization of repair in multiperson conversation: The case of “other”-selection in other-initiated repair sequences. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 44(3), 237–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2011.591835

- Bolden, G. B., Hepburn, A., Potter, J., Zhan, K., Wei, W., Park, S. H., Shirokov, A., Chun, H. C., Kurlenkova, A., Licciardello, D., Caldwell, M., Mandelbaum, J., & Mikesell, L. (2022). Over-exposed self-correction: Practices for managing competence and morality. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 55(3), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2022.2067426

- Daly, J., Willis, K., Small, R., Green, J., Welch, N., Kealy, M., & Hughes, E. (2007). A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014

- De Jaegher, H., Peräkylä, A., & Stevanovic, M. (2016). The co-creation of meaningful action: Bridging enaction and interactional sociology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1693), 20150378. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0378

- Deppermann, A., Mondada, L., Pekarek Doehler, S., Vatanen, A., Endo, T., Yokomori, D., … Schmidt, A. (2021). Early responses in human communication. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 293–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2021.1877516

- Deppermann, A., & Schmidt, A. (2021). Micro-sequential coordination in early responses. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 372–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1842630

- Dingemanse, M., Roberts, S. G., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., Drew, P., Floyd, S., … Enfield, N. J. (2015). Universal principles in the repair of communication problems. PloS one, 10(9), e0136100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136100

- Drew, P. (1997). ‘Open’class repair initiators in response to sequential sources of troubles in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 28(1), 69–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(97)89759-7

- Duran, D., Kurhila, S., & Sert, O. (2022). Word search sequences in teacher-student interaction in an English as medium of instruction context. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(2), 502–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1703896

- Egbert, M. M. (1996). Context-sensitivity in conversation: Eye gaze and the German repair initiator bitte? Language in Society, 25(4), 587–612. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500020820

- Ekberg, K., Hickson, L., & Grennes, C. (2017). Conversation breakdowns in the audiology clinic: The importance of mutual gaze. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 52(3), 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12277

- Floyd, S., Manrique, E., Rossi, G., & Torreira, F. (2016). Timing of visual bodily behavior in repair sequences: Evidence from three languages. Discourse Processes, 53(3), 175–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2014.992680

- Fox, B. (1999). Directions in research: Language and the body. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 32(1–2), 51–59.

- Fox, B., Maschler, S., & Uhmann, S. (2010). A cross-linguistic study of self-repair: Evidence from English, German and Hebrew. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(9), 2487–2505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.02.006

- Girard-Groeber, S. (2020). Swiss German and Swiss German Sign Language resources in repair initiations: An examination of two types of classroom. In R. Wilkinson, J. Rae, & G. Rasmussen (Eds.), Atypical interaction: The impact of communicative impairments within everyday talk (pp. 435–464). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goldin-Meadow, S. (2009). How gesture promotes learning throughout childhood. Childhood Development Perspectives, 3(2), 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00088.x

- Goldin-Meadow, S. (2014). How gesture works to change our minds. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 3(1), 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2014.01.002

- Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation. Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology, 97, 101–121.

- Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. Language in Society, 12(1), 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500009647

- Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

- Goodwin, C. (2003). Conversation and brain damage. Oxford University Press.

- Goodwin, M. H. (1980). Processes of mutual monitoring implicated in the production of description sequences. Sociological Inquiry, 50(3–4), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1980.tb00024.x

- Goodwin, M. H., & Goodwin, C. (1986). Gesture and coparticipation in the activity of searching for a word. Semiotica, 62(1–2), 51–75.

- Greer, T. (2013). Word search sequences in bilingual interaction: Codeswitching and embodied orientation toward shifting participant constellations. Journal of Pragmatics, 57, 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.08.002

- Gullberg, M. (2011). Multilingual multimodality: Communicative difficulties and their solutions in second-language use. In Embodied Interaction: Language and Body in the Material World (pp. 137–151).

- Hayashi, M. (2003). Language and the body as resources for collaborative action: A study of word searches in Japanese conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 36(2), 109–141. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327973RLSI3602_2

- Hayashi, M., Raymond, R., & Sidnell, J. (2013). Conversational repair and human understanding. Cambridge University Press.

- Helasvuo, M.-L., Laakso, M., & Sorjonen, M.-L. (2004). Searching for words: Syntactic and sequential construction of word search in conversations of finnish speakers with Aphasia. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 37(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3701_1

- Jefferson, G. (1984). Transcription conventions. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action (pp. ix–xvi). Cambridge University Press.

- Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols. In Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 24–31). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.125

- Jokipohja, A. K., & Lilja, N. (2022). Depictive hand gestures as candidate understandings. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 55(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2022.2067425

- Kärkkäinen, E., & Thompson, S. A. (2018). Language and bodily resources:‘Response packages’ in response to polar questions in English. Journal of Pragmatics, 123, 220–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.05.003

- Keevallik, L. (2013). The interdependence of bodily demonstrations and clausal syntax. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.753710

- Kendrick. (2015a). The intersection of turn-taking and repair: The timing of other-initiations of repair in conversation. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00250

- Kendrick, K. J. (2015b). Other-initiated repair in English. Open Linguistics, 1, 164–190. https://doi.org/10.2478/opli-2014-0009

- Kim, J.-Y. 2004. Repair in lab hour second language interactions: Cases of Korean Tas and Native English-speaking students. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Texas:.

- Klippi, A. (2014). Pointing as an embodied practice in aphasic conversation. Aphasiology, 29(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.878451

- Klippi, A. (2015). Pointing as an embodied practice in aphasic interaction. Aphasiology, 29(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.878451

- Klippi, A., & Ahopalo, L. (2008). The interplay between verbal and non-verbal behaviour in aphasic word search in conversation. Research in Logopedics. Speech and Language Therapy in Finland, 146–171.

- Klippi, A. (2003). Collaborating in Aphasic group conversation- striving for mutual understanding. In C. Goodwin (Ed.), Conversation and brain damage (pp. 117–143). Oxford University Press.

- Kress, G. (2009). A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge.

- Kunitz, S. 2013. Group planning among L2 learners of Italian: A conversation analytic perspective. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Illinois:.

- Laakso, M. (1997). Self-initiated repair by fluent aphasic speakers in conversation. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Helsinki Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura.

- Laakso, M. (2014). Aphasia sufferers’ displays of affect in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(4), 404–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.958280

- Laakso, M. (2015). Collaborative participation in aphasic word searching: Comparison between significant others and speech and language therapists. Aphasiology, 29(3), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2013.878450

- Laakso, M. (2003). Collaborative construction of repair in aphasic conversation: An interactive view on the extended speaking turns of Wernicke’s aphasics. In C. Goodwin (Ed.), Conversation and brain damage (pp. 163–188). Oxford University Press.

- Laakso, M., & Klippi, A. (1999). A closer look at hint-and-guess sequences in aphasic conversation. Aphasiology, 13(4–5), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/026870399402136

- Laakso, M., & Sorjonen, M.-L. (2010). Cut-off or particle − Devices for initiating self-repair in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(4), 1151–1172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.09.004

- Levinson, S. C. (2015). Other-initiated repair in Yélî Dnye: Seeing eye-to-eye in the language of Rossel Island. Open Linguistics, 1(1).

- Lind, C., Hickson, L., & Erber, N. P. (2004). Conversation repair and acquired hearing impairment: A preliminary quantitative clinical study. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Audiology, 26(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1375/audi.26.1.40.55987

- Manrique, E. (2016). Other-initiated repair in Argentine sign language. Open Linguistics, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0001

- Matsumoto, Y. 2013. Multimodal communicative strategies for resolving miscommunication in multilingual writing writing classrooms. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Pennsylvania State University.

- Mondada, L. (2014). Bodies in action: Multimodal analysis of walking and talking. Language and Dialogue, 4(3), 357–403.

- Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

- Mondada, L. (2019). Contemporary issues in Conversation Analysis. Embodiment and materiality, multimodality and multisensoriality in social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 145, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.016

- Mondada, L. (2021). How early can embodied responses be? Issues in time and sequentiality. Discourse Processes, 58(4), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2020.1871561

- Mortensen, K. (2016). The body as a resource for other-initiation of repair: Cupping the hand behind the ear. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 49(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2016.1126450

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., & McArthur, A. E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Oloff, F. (2018). ‘Sorry?’/‘Como?’/‘Was?’ – Open class and embodied repair initiators in international workplace interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 126, 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2017.11.002

- Pajo, K. (2013). The occurrence of “what,” “where,” “what house” and other repair initiations in the home environment of hearing-impaired individuals. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 48(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00187.x

- Pajo, K., & Klippi, A. (2013). Hearing-impaired recipients’ non-vocal action sets as a resource for collaboration in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 55, 162–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.06.004

- Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Radford, J. (2009). Word searches: On the use of verbal and non-verbal resources during classroom talk. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 23(8), 598–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699200902997491

- Radford, J. (2020). Increasing Learner Authority in the Classrooms of Children with Speech, Language and Communication. In J. Rae, G. Rasmussen, & R. Wilkinson (Eds.), Atypical Interaction: The Impact of Communicative Impairments within Everyday Talk (pp. 289–315).

- Rasmussen, G. (2014). Inclined to better understanding—The coordination of talk and ‘leaning forward’in doing repair. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.10.001

- Rossi, G. (2020). Other-repetition in conversation across languages: Bringing prosody into pragmatic typology. Language in Society, 49(4), 495–520.

- Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation (Vol. I). Blackwell.

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1978). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn taking for conversation. In J. Schenkein (Ed.), Studies in the organization of conversational interaction (pp. 7–55). Academic Press.

- Schegloff, E. A. (1979). The relevance of repair to syntax-for-conversation. In T. Givon (Ed.), Discourse and syntax (pp. 261–286). Brill.

- Schegloff, E. A. (2000). When ‘others’ initiate repair. Applied Linguistics, 21(2), 205–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.2.205

- Schegloff, E. A. (2006). On possibles. Discourse Studies, 8(1), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445606059563

- Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., & Sacks, H. (1977). The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language, 53(2), 361–382. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.1977.0041

- Selting, M. (2009). Gesprächsanalytisches Transkriptionssystem 2 (GAT 2). Gesprächsforschung - Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion, 10, 353–402. http://www.gespraechsforschung-ozs.de/

- Seo, M.-S., & Koshik, I. (2010). A conversation analytic study of gestures that engender repair in ESL conversational tutoring. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(8), 2219–2239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.01.021

- Sert, O. 2011. A micro-analytic investigation of claims of insufficient knowledge in EAL classrooms. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Newcastle:.

- Skelt, L. (2007). Damage control: Closing problematic sequences in hearing-impaired interaction. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics, 30(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.2104/aral0734

- Skelt, L. (2010). “Are you looking at me?” The influence of gaze on frequent conversation partners´ management of interaction with adults with acquired hearing impairment. Seminars in Hearing, 31(2), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1252103

- Skogmyr Marian, K., & Pekarek Doehler, S. (2022). Multimodal word-search trajectories in L2 interaction. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 5(1).

- Stivers, T., & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing response. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1), 3–31.

- Streeck, J., Goodwin, C., & LeBaron, C. (Eds.). (2011). Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world. Cambridge University Press.

- Stuart, N., Whitehouse, A., Palermo, R., Bothe, E., & Badcock, N. (2022). Eye gaze in autism spectrum disorder: A review of neural evidence for the eye avoidance hypothesis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05443-z

- Stukenbrock, A. (2018). Forward-looking. In Depperman & Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (Vol. 293, pp. 31). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tykkyläinen, T. (2010). Child-initiated repair in task interactions. In H. Gardner & M. Forrester (Eds.), Analyzing Interactions in Childhood: Insights from conversation analysis (pp. 227–248). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wiklund, M. (2016). Interactional challenges in conversations with autistic preadolescents: The role of prosody and non-verbal communication in other-initiated repairs. Journal of Pragmatics, 94, 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.01.008

- Wilkinson, R., Beeke, S., & Maxim, J. (2010). Formulating actions and events with limited linguistic resources: Enactment and iconicity in agrammatic aphasic talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1), 57–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903471506

- Wu, R.-J. (2022). Gestural repair in mandarin conversation. Discourse Studies, 24(1), 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614456211037451