ABSTRACT

Our review highlights state-of-the-art conversation analytic (CA) research within adult outpatient secondary care settings and how this research has been applied to clinical practice, provides reflections, and considers fruitful areas for future research. Findings from 128 articles were synthesized according to five clinical activities that have been the focus of CA research thus far: (1) information gathering and patients’ descriptions of their symptoms/condition; (2) information delivery, including test results and diagnosis; (3) decision making about goals, treatment, and future care; (4) interacting about sensitive issues, including patients’ emotions and psychosocial concerns; and (5) managing the interactional role of companions accompanying patients in adult outpatient secondary care appointments. Research in these settings has been used in healthcare policy/guidelines and designing training interventions for clinical practice. Within future CA research in outpatient secondary care, there is scope for more longitudinal studies and further exploring interactions in multidisciplinary care. Data examples are in multiple languages.

Overview and background

Modern, integrated healthcare systems consist of a complex network of organizations whose primary purpose is to promote, restore, or maintain health (Erdmann et al., Citation2013; Pinto Júnior et al., Citation2016; WHO, Citation2000). The first point of care is typically primary care, responsible for preventative care, acute care, and treatment of common viruses and diseases (Pinto Júnior et al., Citation2016). Sometimes patients need more specialized treatment from other types of clinicians/healthcare providers (e.g., oncologists, cardiologists, allied health professionals), and specialized care typically falls under “secondary care” (Erdmann et al., Citation2013). Given that many countries face aging populations and growing prevalence of complex chronic conditions that require ongoing specialized treatment, there is increasing need for secondary care services worldwide (WHO, Citation2016). The proportion of patients attending primary care who are referred to secondary care each year can range from 13% to 37% (e.g., Forrest et al., Citation2002; Ringberg et al., Citation2013). Much of secondary care is provided in an outpatient setting, whether it is in a hospital outpatient clinic or a community clinic. Depending on the policies of the nation’s health system, patients may be required to see a primary care provider for a referral prior to being able to access secondary care (e.g., the United Kingdom, Finland, and the Netherlands), or they may also be able to self-refer to the service (e.g., the United States, Australia, China, and Singapore; Health care, Citation2020). Allied health professionals—such as physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and dietitians—also frequently work in secondary outpatient care, accessed either through patient self-referral or through physician referral (Health care, Citation2020).

When (self-)referred in an outpatient secondary care, the type of specialist the patient visits is specific to the part of the body or body system, disease, or condition that is of concern (e.g., attending a cardiology appointment for heart concerns). However, further testing within secondary care services may reveal that a different specialty is required, and patients may then be referred to other secondary care services. In addition, some patients with major, chronic, and/or complex conditions (e.g., cancer patients) may need to attend appointments for several different specialists simultaneously.

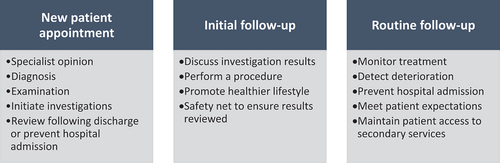

Patients in secondary care typically visit a specialist for ongoing appointments over a sometimes-lengthy treatment period. Testing/assessment, diagnosis, and treatment typically occur across many appointments and may continue over weeks, years, or a lifetime. The function and length of individual appointments can thus vary, depending on the stage of a patient’s journey (Royal College of Physicians, Citation2018). shows the activities that are key functions of different types of appointments across the outpatient secondary care journey, according to the UK Royal College of Physicians (Citation2018) (this may differ slightly depending on the healthcare system).

Figure 1. Example functions of secondary care appointments (UK Royal College of Physicians, Citation2018).

Depending on the health system (and whether a patient is attending services as a public or private patient), patients in secondary care may have appointments with a specific specialist across their lifespan, or they may see different specialists within and across their ongoing appointments. In any given appointment, the patient may thus either have an existing relationship with the clinician or be seeing the clinician for the first time.

Outpatient secondary care is thus a key and complex part of modern healthcare systems worldwide. Direct observation of outpatient secondary care appointments can open the black box of how this type of care happens, including how clinician(s) and patient interact to co-develop an appreciation of the patient’s problem, make decisions on how to treat it, and (re-)negotiate ongoing adherence to the decided course(s) of action (Montori, Citation2021). It is in and through the clinician–patient encounter that many of the macro-level secondary care policies and procedures can be seen to be transformed (or not) into clinical care (Golembiewski et al., Citation2023; Montori, Citation2021). There is a growing number of studies using direct observation to examine outpatient secondary care, but this research has not often been synthesized and reviewed. One systematic review of video-based observation research in outpatient healthcare settings was conducted recently (Golembiewski et al., Citation2023); however, this review included both primary and secondary outpatient settings and did not include all of the CA research that has been conducted in this area. CA research specific to outpatient secondary care settings has shed light on how the delivery of this specialized type of care is accomplished within interaction, including how clinicians and patients negotiate and manage both clinical tasks and their therapeutic relationship throughout and across appointments.

This narrative review will highlight key findings of the “state-of-the-art” of research using CA to examine interaction in adult outpatient secondary care, highlight how this research has been applied to change clinical practice, provide reflections on existing research, and consider potential fruitful areas for future research in secondary care settings.

Method

For this review, we have adopted a narrative approach to highlight the state-of-the-method (Paré & Kitsiou, Citation2017). However, in searching for the literature, we were informed by the systematic approach for searching for CA literature described by Parry and Land (Citation2013). The literature search was conducted in January–March 2022. An updated search was conducted in April 2023. Inclusion criterion for the search included that CA was the key methodology for analysis, data were collected within an adult outpatient secondary care setting, and data exemplars were presented with Jeffersonian transcription and analyzed in the results of the article. Intervention studies were included if the intervention was designed from CA findings (with CA analysis shown or cited). Allied healthcare (including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, audiology, and speech therapy) was included as secondary care for the purposes of this review (Health Care, Citation2020); however, dentistry and pharmacy were excluded, as we treated them as primary care. Articles in pediatric, telehealth, and end-of-life/palliative care settings were excluded, as these are examined in other reviews in this special issue. Articles related to mental health were excluded, as these have been covered in a previous review in this journal and in a recent handbook (O’Reilly & Lester, Citation2016; Peräkylä, Citation2019). Articles analyzing in-patient hospital care were also excluded.

Three databases were searched: PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Our search strategy can be found in Supplementary File 1. Having screened findings and identified publications for inclusion, forward and backward citation checking was applied by all authors. Further, a hand-search snowballing technique was used to search for relevant book chapters.

Basic information was extracted for each article, including the secondary care setting, country and language(s) in which data were collected, participant type and numbers, amount of data, and whether audio and/or video data. We also extracted a description of the key practices examined in the analysis. These practices were inductively analyzed and synthesized in relation to five key themes. These themes cover the main, but not all, clinical activities that have been examined in the CA literature of adult outpatient secondary care interactions.

The current state of the art

In total, 128 articles were included in the review, spanning a range of outpatient secondary care settings. Articles date from 1990 to early 2023. Data were collected in 17 countries—the majority from the United Kingdom (39%) and the United States (20%)—and in 11 languages—the majority in only English (74%). Supplementary File 2 provides details of each article reviewed.

Key findings, highlighting the state-of-the-art, are presented below according to five clinical activities that have had the most focus of the CA outpatient secondary care literature thus far: (1) information gathering and patients’ descriptions of their symptoms/condition; (2) information delivery, including test results and diagnosis; (3) decision making about goals, treatment, and future care; (4) interacting about sensitive issues, including patients’ emotions and psychosocial concerns; and (5) managing the interactional role of companions accompanying patients in adult outpatient secondary care appointments (by companions, we refer to family members, friends, or significant others). Of the articles reviewed, 90% could be categorized into one or more of these themes. See Supplementary File 2 for other interactional activities that have also received attention to a lesser extent.Footnote1

Although there is no established structure of phases or core activities across the broad range of outpatient secondary care appointments, we have presented the first three sub-sections below in the order in which they have typically been found to occur within appointments. We then present the final two clinical activities, which occur across various phases of appointments.

Information gathering and patients’ descriptions of their symptoms/condition

A substantial body of CA research, across various outpatient secondary care settings, has explored clinicians’ information gathering practices and patients’ descriptions of their symptoms/condition (n = 28 articles; 22%). It is important to note that an even larger body of CA research in primary care examines similar issues: For example, see Barnes and Woods (Citation2024), who review and provide examples of patients’ agenda-setting practices, ideas, concerns, and expectations. The outpatient secondary care research we reviewed suggests that patients’ descriptions of their symptoms/conditions have variable accomplishments depending on the potential outcomes for which they are advocating. For example, sometimes patients’ descriptions involve attempts to make their case “doctorable” (i.e., they have a problem that is worthy of medical attention, advice, and possibly treatment; Heritage & Robinson, Citation2006), such as when patients seeking breast surgery attempt to persuade physicians that their concerns about breast asymmetry are valid and qualify for surgery (Mace et al., Citation2021). However, other research has found that patients sometimes downplay or minimize their symptoms/condition (Beach, Citation2019; Ekberg et al., Citation2016; Galatolo & Fasulo, Citation2022) or “justify wellness” to display resilient stances toward health and healing (Beach, Citation2013). Within audiology appointments in Australia, patients who played down their hearing loss during the history-taking phase of the appointment were found to be more likely to resist a recommendation of hearing aids in the management phase of the appointment (Ekberg et al., Citation2016). Extract (1) is an example:

Extract (1): [CO5-1 history-taking] from (Ekberg et al., Citation2016)

In response to the audiologist’s initial question, the patient downplays the impact of her hearing difficulties on her everyday life, attributing her hearing troubles to external factors and providing an example of when she heard well. Later in the appointment, following a diagnosis of hearing loss, the patient rejects the recommendation for hearing aids. Patients may thus play down their symptoms when a treatment option is unfavorable to them (Beach, Citation2013; Ekberg et al., Citation2016; Galatolo & Fasulo, Citation2022).

Patients’ descriptions may also orient to multiple, competing agendas in appointments. A study in a prosthesis clinic in Italy found that patients acknowledged their unpleasant post-amputation sensations but also minimized the pain (Galatolo & Fasulo, Citation2022). This minimization of pain could be seen as a way of delicately balancing two competing agendas of the appointment: Reporting any discomfort is important for assessment of the healing process and identifying any post-operation problems, but if the patient is feeling too much pain, then the prosthesis may be delayed or denied, which may be against the patient’s interest. Patients’ descriptions of their symptoms can thus be seen here to delicately orient to their agenda for the appointment, including their preferred treatment option.

Together, this research highlights that patients’ descriptions can have important consequences for differential diagnosis, identifying patients’ agendas and forecasting how patients will respond to treatment recommendations.

Information delivery, including test results and diagnosis

Within outpatient secondary care, information delivered by clinicians to patients in an appointment can include the delivery of test results, a diagnosis, and/or the provision of general information about a (new or previously diagnosed) condition. Our review identified 20 articles (16%) examining this clinical activity.

The medical conditions under investigation in secondary care are often pathologically complex and involve diagnostic uncertainty. CA research (including in oncology, neurology, and genetic/antenatal counseling settings) has focused on how test results and diagnoses are delivered and how uncertainty is managed within the interaction. Across different settings, clinicians have been found to use the following interactional resources to display uncertainty when delivering a diagnosis or test result: using phrases such as “the most likely” or “this probably is” (Dooley et al., Citation2018); perturbations and “dysfluencies,” such as self-repair (Monzoni et al., Citation2011; Peel, Citation2015); declaring themselves personally accountable (with statements such as “I think” or “I believe”; Monzoni et al., Citation2011); hedging devices, imprecise and noncommitting formulations, and explicit descriptions of results as estimations (Pilnick & Zayts, Citation2014); and providing general information about a condition but using hedging devices when commenting on a patient’s specific situation/symptoms (Lehtinen, Citation2013). Clinicians thus attend to the need to display the uncertainty surrounding diagnosis and/or test results to patients within their secondary care appointments, which adds complexity to the interaction.

In addition to uncertainty, whether the diagnosis/test result is good or bad news also must be interactionally managed, and clinicians and patients may have differing perspectives on the valance of news. In oncology, one prominent result is “stable” cancer (Beach, Citation2021b). Oncologists announce “stable” as good news, whereas patients may display lack of enthusiasm and even disappointment:

Extract (2): [OC D9 P6:4–6] from (Beach, Citation2021b)

Although the clinician treats controlling cancer and minimizing side effects (Lines 2–3) as good news, in response the patient begins to cry, states being “worked up,” and describes “stable” as a disappointment (Lines 8–9). In most instances, patients resisted and questioned why “stable” is good, especially when they must endure continued treatments with minimal chances for shrinking tumors or remission. These contrasting orientations to “stable” reveal how patients’ and oncologists’ different stances toward news is displayed and managed in the interaction.

Patient responses to news/information delivery sometimes involve minimal receipt (Peräkylä & Silverman, Citation1991; Pilnick, Citation2002), but they have also been found to engage in various actions that extend the information provision sequence, including asking questions (Peräkylä & Silverman, Citation1991), requesting further information (Fasulo et al., Citation2016), providing candidate understandings (Lehtinen, Citation2005), or presenting discrepant information from other sources (Lehtinen & Kääriäinen, Citation2005).

In sum, existing CA research has found that delivering information—including test results, a diagnosis, or an update on disease progression in outpatient secondary care—is a complex activity. It often involves displaying uncertainty and orienting to the valance of the news (e.g., good/bad), which may or may not match with the patient’s perspective. Patients’ responses can be varied and sometimes lead to extended information delivery sequences.

Decision making about goals, treatment, and future care

Decision-making practices, and the extent to which they encourage patient involvement, have been the focus of a large proportion of the CA research in outpatient secondary care (n = 38 papers, 30%). There are often multiple options for treatment/care in these settings, and sometimes there are uncertainty and differing opinions about the “best” course of action. Within secondary care appointments, there may also be a need for ongoing testing before treatment can begin/continue. Test ordering has been found to be an additional normative activity in neurology that is both “treatment-oriented” (in the longer term being in the service of eventual diagnosis) and a “stepping-stone,” displacing treatment decisions (in the here and now; Toerien et al., Citation2020; Zhao & Ma, Citation2020).

Some research (including in HIV counseling, gynecology, audiology, oncology, and physiotherapy appointments) has found that treatment decisions are mostly clinician-led, with minimal patient involvement in joint decision making (e.g., Boluwaduro, Citation2020; Ekberg et al., Citation2017; Mahmoodi et al., 2019; Ostermann, Citation2021; Parry, Citation2004; Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2020). Some practices, such as collaborative goal setting with patients, are often avoided altogether (Parry, Citation2004; Schoeb et al., Citation2014). A common way that clinicians approach decision making about treatment involves delivering recommendations and suggestions (e.g., “my suggestion would be X”; e.g., Chappell et al., Citation2018; Tate, Citation2019; Toerien et al., Citation2011). Clinicians sometimes provide diagnostic information or hypothetical scenarios (if diagnostic information is ambiguous) to formulate logical consequences for their treatment recommendations (Fatigante et al., Citation2016). Recommendations designedly proffer the option the clinician thinks are best and have been found to nearly always end in the patient’s agreement to undertake the explicit course of action (Chappell et al., Citation2018; Toerien et al., Citation2011). This frequency of clinician-led decision-making practices (in which the clinician asserts agency over making a unilateral recommendation) may partly be because facilitating patient involvement is a complex interactional achievement that requires ongoing interactional management by both clinician and patient, including touching on delicate/sensitive topics and going outside the patients’ knowledge/understanding of what is possible (Parry, Citation2004; Schoeb, Citation2009; Schoeb et al., Citation2014).

Other CA research (including antenatal, genetic counseling, neurology, audiology, and oncology appointments) has found evidence of decision-making practices that facilitate patient involvement (e.g., Cole et al., Citation2021; Pilnick & Zayts, Citation2012, Citation2016, Citation2019; Wessels et al., Citation2015). Clinicians have been found to facilitate patient involvement with inquiries asking for patients’ opinions (Ruusuvuori et al., Citation2020) or patient view elicitors (e.g., “so what do you think?”; Reuber et al., Citation2015). Another way that clinicians have been found to invite patient involvement in decision making is through option listing (Ekberg et al., Citation2017; Tate & Rimel, Citation2020; Toerien, Citation2021; Toerien et al., Citation2011, Citation2013). Option listing involves clinicians listing alternatives from which the patient might choose, sometimes initially forecasting such a choice (e.g., “we can do a number of things”). Unlike a response to a recommendation, simple acceptance is not an adequate next turn after option listing. Option listing creates more room for maneuver than other recommendation formats, and thus decision making lies more in the patient’s domain. Treatment decisions are therefore more of a joint negotiation. However, a study in neurology found that options provided by the neurologist are not always described in equivalent terms and often include an implicit recommendation for a particular option, conveying the neurologist’s preference within the options themselves (Toerien et al., Citation2011). For example, prior to Extract (3) from a neurology appointment in the United Kingdom, the clinician has proposed psychotherapy as a possible course of action and has also mentioned medication and further testing, which he has ruled out as options. He then provides the below menu of two alternatives:

Extract (3): [Patient 2] from (Toerien et al., Citation2011, p. 318)

Despite presenting two options here, the neurologist states his preference for psychotherapy as being the “best way forward” (Lines 11–13). Option listing can nevertheless be used to push for the neurologist’s preferred option (Reuber et al., Citation2015). A study in oncology also found that options were constrained in early disease phases, and rescinded in later phases addressing more advanced cancer, to assist patients in realizing possibilities for cure are diminished. Clinicians in oncology can also persuasively invoke death to lobby and advocate for treatment options and to counter possible patient resistance (e.g., Gill, Citation2019; Gutzmer & Beach, Citation2015; Tate, Citation2020).

Combined, the body of CA research on treatment decision making in outpatient secondary care has highlighted the ways that the introduction of, and decision making about, interventions have been found to recurrently limit patient involvement. Inquiries asking for patients’ opinions and option listing are two ways in which patient involvement can be facilitated, although clinician biases can still sometimes be conveyed in the way in which options are presented.

Interacting about sensitive issues including patients’ emotions and psychosocial concerns

The review also found a substantial body of CA research in outpatient secondary care that has explored how clinicians and patients interact about sensitive issues, including patients’ displayed emotions and psychosocial concerns (n = 21, 16%).

Sensitive issues

CA research in secondary outpatient care has explored how the sensitive nature of discussions between clinician and patient is managed within the interaction during appointments (on CA research on sensitive discussions, see also Parry, Citation2024). This research stems from foundational CA research conducted by Silverman, Peräkylä, and colleagues in HIV clinics in 1990s (Peräkylä, Citation1993; Peräkylä & Bor, Citation1990; Silverman & Bor, Citation1991; Silverman & Peräkylä, Citation1990). Across a series of articles, this research showed how delicate or sensitive issues (e.g., patients’ sexuality, references to partners, and addressing patients’ fears about the future) were often interactionally delayed, involved perturbations within the talk, involved the use of neutral terms, and were spoken about within hypothetical or universal scenarios (Peräkylä, Citation1993; Peräkylä & Bor, Citation1990; Silverman & Bor, Citation1991; Silverman & Peräkylä, Citation1990). Clinicians were also found to build on patients’ prior talk to transition into talk about sensitive issues (Peräkylä, Citation1993). These foundational findings have been supported in subsequent research, for example, within HIV care, dietary counseling, and internal medicine appointments (e.g., Briedé et al., Citation2021; Sheon & Lee, Citation2009; Tapsell et al., Citation2000).

Sensitive discussions in secondary care settings can also involve talk about “risky” behaviors that could worsen conditions. For example, in settings such as HIV, dietary, obesity, and diabetes clinics, patients have been shown to use various interactional resources to present themselves as reasonable and responsible people (Lee & Sheon, Citation2008; Webb, Citation2009). Humor has also been found to be used in appointments as a face-saving strategy when talking about morally charged, face-threatening acts such as nonadherence to diabetes treatment plans (Schöpf et al., Citation2017). This cumulative research has demonstrated that clinicians and patients collaboratively manage the sensitive, delicate, and sometimes moral nature of seeking and treating conditions within secondary care.

Displayed emotions and psychosocial concerns

A significant body of CA research in oncology has focused on patients’ initiations of displayed emotion and psychosocial concerns and how clinicians respond to them. During oncology appointments, when patients announce good news, seek hopeful reassurance about their condition, talk about cancer pains, display troubled laughter, or cry, “empathic opportunities” (Suchman et al., Citation1997) are created for physicians to acknowledge, confirm, and commiserate with patients’ problems (Beach, Citation2022; Beach & Prickett, Citation2017; Chapman & Beach, Citation2020). An example of an empathic opportunity, in response to displayed emotion, and the clinician’s response can be seen in Extract (4), in which the patient has just received a second diagnosis of recurrent and serious breast cancer (Beach, Citation2022). Prior to this extract, the patient invokes “wo::w, ba:m.” to describe her reaction to receiving a second diagnosis of recurrent and serious breast cancer (Beach, Citation2022). She then continues with “ = we’re stro:ng, it’s ha:rd.” and begins crying. In response, the doctor stands, touches the patient’s knee, and offers a tissue. The patient then apologizes (Line 1):

Extract (4): [OC11:1:31–33] from (Beach, Citation2022)

In these brief moments, the doctor offers quiet reassurance (Line 2) to comfort a patient facing likely terminal cancer. By standing with and gazing directly at the patient and touching her knee with both hands, the doctor enacts compassionate witnessing that does not rush no discount the patient’s expression of her woundedness. In other secondary care settings, ways in which clinicians have been found to attend to patients’ displayed emotions and psychosocial concerns include the use of prompts, second questions, formulations (proposing a version of events that follows directly from the patient’s prior talk; Antaki, Citation2008), and aligning or redirecting positive feedback (Weiste, Citation2016).

Empathic responses from clinicians (such as that in Extract (4)) have been found to not always be common, however, with research in oncology showing that 70% of all empathic opportunities are missed by clinicians who did not directly address, or are minimally receptive to, emotions or concerns raised by patients when enacting fears, uncertainties, and hopes (Beach & Dozier, Citation2015; Beach et al., Citation2005; Easter & Beach, Citation2004; for an extended example of this type of practice from oncology outpatient appointments, see Beach et al., Citation2005, pp. 902–905). Research in allied health settings has also found that clinicians sometimes pursue their own agendas (shifting topic, not engaging with patients’ responses, and/or having selective treatment of patients’ concerns) without attending to patients’ psychosocial concerns (e.g., Ekberg, Grenness et al., Citation2014). This research has shown that when patients’ concerns are not attended to, patients persistently reraise their concerns in subsequent turns, leading to expanded sequences of interaction (Ekberg, Grenness et al., Citation2014). Disattending to concerns can thus, perhaps counterintuitively, derail the agenda of the appointment.

Managing the interactional role of companions accompanying patients in adult secondary care outpatient appointments

The conditions/diseases that are managed in secondary care often affect the lives not only of the patient but also of his or her companions. Patients are often encouraged to bring companions to secondary care appointments. The role of companions in these appointments has been examined across a range of settings (e.g., neurology, oncology, audiology, and genetic counseling; n = 8 papers, 6%). During information-gathering sequences, companions have been found to self-initiate their involvement in the interaction, expanding on patients’ descriptions or even interrupting or responding to questions intended for the patient, particularly if they have not been provided their own opportunity to speak (e.g., Ekberg et al., Citation2015; Robson et al., Citation2016). When companions self-initiate talk, clinicians have sometimes been observed to try to redirect the conversation back to the patient, limiting companion involvement (Ekberg et al., Citation2015; Robson et al., Citation2016). Companions’ descriptions of the patient’s symptoms/conditions can be in disagreement with the patient, and these competing perspectives must be managed by the clinician within the interaction (Ekberg, Meyer et al., Citation2014; Pilnick, Citation2002). In oncology, companions were found to work to preserve the legitimacy and responsibility of the patient as primary agent and reason for the encounter by initiating actions attempting to strengthen, support, and facilitate the patient’s aims for the visit (e.g., monitoring, sneaking, brokering, and negotiating actions; Fatigante et al., Citation2021). For example, see Extract (5) from an oncology appointment in Italy:

Extract (5) [Excerpt 3. Site 1] from (Fatigante et al., Citation2021)

The companion in this extract influences the content of the patient’s response to the clinician. However, by whispering and avoiding eye gaze with her interlocutors, her turn can be heard as a prompt to the patient rather than her being the author of the report.

Companions’ contributions to information gathering can aid diagnosis. For example, in neurology it has been determined that accompanying others can help to negotiate a clearly communicated diagnosis of dementia (Dooley et al., Citation2018; Peel, Citation2015). The nature of companions’ interaction has also been found to help in the differential diagnosis between epilepsy and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) as well as dementia and functional memory disorder (FMD Elsey et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2016; Robson et al., Citation2016).

Additionally, companions in neurology appointments have been found to support decision making, help to resist treatment, and advocate for test ordering (Reuber et al., Citation2015; Toerien et al., Citation2020). In oncology, companions have also been found to offer social support and aid in decision making (Huber et al., Citation2016). But spouses can also enact dominance by interrupting patients and physicians, not asking for clarifications, behaving as primary decision makers, and constraining patients/spouses from expressing their thoughts and opinions (Huber et al., Citation2016).

In summary, this state-of-the-art review identified five key clinical tasks that have been the focus of CA research in a range of outpatient secondary care settings. Research examining patient descriptions of their symptoms/condition has found that these descriptions can have important consequences for differential diagnosis, identifying patients’ agendas and forecasting how patients will respond to treatment recommendations. Clinicians’ information delivery, including test results and diagnosis, often involves the interactional management of uncertainty and orienting to the valance of news, which may not always match the patient’s perspective of the news. Research on decision making about treatment/intervention has found that the extent to which the patient is involved in the decision-making process can be varied. Patient involvement can be facilitated through option listing, although clinician preferences can still sometimes be conveyed in the way options are presented. Clinicians and patients collaboratively manage the sensitive, delicate, and sometimes moral nature of seeking and treating conditions in secondary care. Patients have been shown to display emotion and raise psychosocial concerns in outpatient secondary care appointments, which are responded to in variable ways by clinicians. Companions’ involvement in the interaction during outpatient secondary care appointments can impact the interaction in variable ways. Together, the research reviewed provides insights into how these crucial clinical tasks are jointly accomplished by clinicians, patients, and companions (if present) within a range of adult outpatient secondary care settings.

Applications

Findings from CA research in outpatient secondary care have been integrated into policy and guidelines for clinical practice. For example, CA research in audiology that has focused on addressing patients’ psychosocial concerns (Ekberg, Grenness et al., Citation2014) and involving companions (Ekberg et al., Citation2015) has been used in clinical guidance documents, including the British Society of Audiology’s “Principles for Rehabilitation for Adults in Audiology Services” (Ekberg et al., Citation2016) and the Welsh government’s “Quality Standards for Adult Hearing Rehabilitation Services” (Ekberg et al., Citation2016). In addition, CA research in neurology has been included in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) training resources for shared decision making (NICE, 2021)Footnote2, in particular in the training module on “Consultation Skills,” which can be accessed at https://sway.office.com/YYCtby08BTJQGjPL?ref=Link.

CA outpatient secondary care research has also been used to develop clinical training interventions. For example, over a series of studies in neurology, patients’ extended descriptions of their symptoms have been shown to aid the differential diagnosis between epilepsy and “psychogenic” nonepileptic seizures (PNES; Ekberg & Reuber, Citation2015; Pevy et al., Citation2021; Plug et al., Citation2009; Robson et al., Citation2012; Schwabe et al., Citation2007) and between dementia and other functional memory disorders (FMD) (Alexander et al., Citation2019; Elsey et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2016, Citation2020; Mirheidari et al., Citation2017, Citation2016; Reuber et al., Citation2018). The findings in this body of research reveal interactional profiles (generated by the cumulative identification of recurring features of talk associated with each diagnostic criterion) that can be used for differential diagnosis. For example, people with dementia are likely to be accompanied to the clinic, are less likely to be concerned about their memory problems (as compared to their companions), defer answers to questions to their companions, and will not respond fully to compound questions (Elsey et al., Citation2015; Jones et al., Citation2016). People with epilepsy initiate discussion and detailed descriptions of their seizure symptoms and use epilepsy-specific terminology when describing their seizure experiences; also, when asked by the clinician what others think of their seizures (e.g., “What do your friends tell you about the seizures?”), they normalize or downplay third-party references (e.g., “Well not really,” see Robson et al., Citation2012, p. 798; Ekberg & Reuber, Citation2015; Plug et al., Citation2009; Robson et al., Citation2012; Schwabe et al., Citation2007).

Based on these findings, an intervention has been developed to train neurologists to change their history-taking practices to (1) elicit longer, uninterrupted descriptions of patients’ seizures and (2) be able to identify the interactional profiles within patients’ seizure descriptions (Jenkins et al., Citation2015; Jenkins & Reuber, Citation2014). Furthermore, these CA-derived profiles have been used to underpin artificial intelligence (AI), using automatic speech recognition software and providing proof-of-principle that a machine learning approach can help in differential diagnosis (Mirheidari et al., Citation2017, Citation2016; Pevy et al., Citation2021). One application in neurology, CognoSpeak, has been piloted and was effective in aiding the differential diagnosis of memory complaints (O’Malley et al., Citation2021). In addition, CA research on cancer has been adapted into two nationally disseminated films as resources for improving oncology interviews (Beach, Citation2021a, Citation2021c). Together, this exemplary research has shown that CA communication interventions can significantly change clinicians’ communication practices in neurology (Jenkins et al., Citation2015) and how patients and family members manage cancer (Beach et al., Citation2016), and paves the way for other interventions to be developed in this area based on CA findings in secondary care.

Issues for reflection

The literature in this review covers a broad range of adult outpatient secondary care settings across several countries. Most of the research thus far, however, has come from the United Kingdom and the United States (59% combined) and involves English-language data (74%). More research is needed from other countries and healthcare systems, particularly in South America, Asia, and Africa. Furthermore, patient demographics (other than their clinical diagnosis) have been rarely reported (with some exceptions, e.g., Beach & Dozier, Citation2015; Dooley et al., Citation2018), so it is unknown whether identified communication practices are representative of interactions with a broad range of patients and companions. This type of data will be useful in future studies to allow judgments to be made about inclusivity and the sociodemographic impacts on treatment and care.

This review identified some similar findings across different outpatient secondary care settings within each of key themes. This result suggests that there may be some clinical activities that are ripe for comparisons across different interactions/settings and that findings may be generalizable more broadly within secondary care. There may also be clinical activities that occur in some outpatient secondary care settings but not in others (e.g., test ordering, treatment option listing), but this remains an empirical question until these activities have been explored in more settings. Collecting data from a large range of secondary care settings is essential to fully open the black box of how care gets done in this broad healthcare setting. There are also phases of the appointment and other clinical activities that have received less attention in the literature so far and require further research across different secondary care settings (e.g., openings, establishing the reason for the visit, physical examination, closings).

In addition to having clinical application, the studies in this review contribute to CA research beyond healthcare. An example includes the management and negotiation of epistemic stance (who knows what and who knows better; Heritage & Raymond, Citation2005) and deontic stance (who has the right to decide; Stevanovic & Peräkylä, Citation2012). For example, managing diagnostic uncertainty involves clinicians displaying a downgraded epistemic stance in relation to their diagnostic news/information delivery. The large body of research exploring treatment decision making, and the extent to which the patient is involved in decisions, reveals the complexity of managing both epistemic and deontic stance in social interaction and who ultimately has the knowledge and rights to make decisions in these settings. Furthermore, given that clinicians and patients across various secondary care settings often seem to interact about sensitive issues, display emotion, and orient to a positive/negative valance of their talk, the management of emotional stance of participants is also highly relevant. Thus, outpatient secondary care is an ideal setting to examine the interface between the three orders in the organization of human action proposed by Stevanovic and Peräkylä (Citation2014).

Another issue for reflection is that, although we attempted to conduct a wide and inclusive search of the literature, as has been identified in previous CA reviews (e.g., Parry & Land, Citation2013), not all CA research appears in the electronic databases, so snowballing search techniques are required. This issue was particularly acute for this review when searching for literature across such a broad range of healthcare settings. We thus do not claim that this review is exhaustive of all existing CA research in adult outpatient secondary care.

The future of CA in secondary care

There is still much to be gained from future CA research in outpatient secondary care. Much of the research thus far has been based on video recordings of single appointments with a clinician and patient (see Supplementary File 2). As secondary care occurs over multiple appointments, and negotiating diagnosis and treatment is often an ongoing process rather than a single event, there is a need for more longitudinal studies in secondary settings (e.g., Beach, Citation2021b). In addition, in many modern health systems there is an increasing tendency to have interdisciplinary secondary care appointments, with patients seeing multiple clinicians from different specialties at the same time. More research is needed to explore the impact of multiple clinicians on the interaction within clinical appointments (for examples, see Galatolo & Margutti, Citation2016; Pichonnaz et al., Citation2021). Early research in this area suggests that when multiple clinicians are present, the interaction among clinicians can take over, to the detriment of the patient’s involvement (Galatolo & Margutti, Citation2016). Given that video recording has become increasingly common over audio recording for CA studies, further CA studies might also build on the growing body of research examining multimodal aspects of outpatient secondary care, including gaze, gesture, and touch (for some existing examples, see Beach, Citation2019; Sterponi et al., Citation2021). Finally, the substantial body of descriptive research already conducted in secondary care settings sets the stage for more CA-based communication interventions designed to enhance quality of care.

Supplemental Materia

Download Zip (431 KB)Supplemental Materia

Download Zip (529.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download Zip (466.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2024.2305042.

Notes

1 Supplementary files are available via the online version of this article.

2 The NICE guidelines in the United Kingdom are evidence-based recommendations for the health and social care sector, developed by independent committees, including professionals and lay members, and consulted on by stakeholders.

References

- Alexander, M., Blackburn, D., & Reuber, M. (2019). Patients’ accounts of memory lapses in interactions between neurologists and patients with functional memory disorders. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12819

- Antaki, C. (2008). Formulations in psychotherapy. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen, & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis of psychotherapy (pp. 26–42). Cambridge University Press.

- Barnes, R., & Woods, C. (2024). Communication in primary healthcare: A state-of-the-art review of conversation-analytic research. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 57(1), 7–37.

- Beach, W. A. (2013). Patients’ efforts to justify wellness in a comprehensive cancer clinic. Health Communication, 28(6), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.704544

- Beach, W. A. (2019). “Tiny tiny little nothings”: Minimization and reassurance in the face of cancer. Health Communication, 34(14), 1697–1710. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1536945

- Beach, W. A. (2021a). A journey through breast cancer. USA Public Broadcasting Systems (PBS): National Education Televisions Association (NETA).

- Beach, W. A. (2021b). Managing “stable” cancer news. Social Psychology Quarterly, 84(1), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272520976133

- Beach, W. A. (2021c). When cancer calls. USA Public Broadcasting Systems (PBS): National Education Televisions Association (NETA).

- Beach, W. A. (2022). Enacting woundedness and compassionate care for recurrent metastatic breast cancer. Qualitative Health Research, 32(2), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211050907

- Beach, W. A., & Dozier, D. M. (2015). Fears, Uncertainties, and hopes: Patient-initiated actions and doctors’ responses during oncology interviews. Journal of Health Communication, 20(11), 1243–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018644

- Beach, W. A., Easter, D. W., Good, J. S., & Pigeron, E. (2005). Disclosing and responding to cancer “fears” during oncology interviews. Social Science and Medicine, 60(4), 893–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.031

- Beach, W. A., Dozier, D. D., Buller, M. K., Gutzmer, K., Fluharty, L., Myers, V. H., & Buller, D. B. (2016). The Conversations about Cancer (CAC) Project - Phase II: National findings from watching when cancer calls … and implications for Entertainment-Education (E-E). Patient Education & Counseling, 99(3), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.10.008

- Beach, W. A., & Prickett, E. (2017). Laughter, humor, and cancer: Delicate moments and poignant interactional circumstances. Health Communication, 32(7), 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1172291

- Boluwaduro, E. (2020). “You must adhere strictly to the time and days of intake”: Medical advice and negotiations of medical authority in nigerian HIV consultations. Linguistik Online, 102(2), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.102.6812

- Briedé, S., van Charldorp, T. C., & Kaasjager, K. A. (2021). Discussing care decisions at the internal medicine outpatient clinic: A conversation analysis. Patient Education and Counseling.

- Chapman, C. R.& Beach, W. A. (2020). Patient-initiated pain expressions: Interactional asymmetries and consequences for cancer care. Health Communication, 35(13), 1643–1655.

- Chappell, P., Toerien, M., Jackson, C., & Reuber, M. (2018). Following the patient’s orders? Recommending vs. offering choice in neurology outpatient consultations. Social Science & Medicine, 205, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.03.036

- Cole, L., LeCouteur, A., Feo, R., & Dahlen, H. (2021). “Cos you’re quite normal, aren’t you?”: Epistemic and deontic orientations in the presentation of model of care talk in antenatal consultations. Health Communication, 36(3), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1692492

- Dooley, J., Bass, N., & McCabe, R. (2018). How do doctors deliver a diagnosis of dementia in memory clinics? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(4), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.64

- Easter, D. W., & Beach, W. (2004). Competent patient care is dependent upon attending to empathic opportunities presented during interview sessions. Current Surgery, 61(3), 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cursur.2003.12.006

- Ekberg, K., Barr, C., & Hickson, L. (2017). Difficult conversations: Talking about cost in audiology consultations with older adults. International Journal of Audiology, 56(11), 854–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2017.1339128

- Ekberg, K., Grenness, C., & Hickson, L. (2014). Addressing patients’ psychosocial concerns regarding hearing aids within audiology appointments for older adults. American Journal of Audiology, 23(3), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0011

- Ekberg, K., Grenness, C., & Hickson, L. (2016). Application of the transtheoretical model of behaviour change for identifying older clients’ readiness for hearing rehabilitation during history-taking in audiology appointments. International Journal of Audiology, 55(sup3), S42–S51. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2015.1136080

- Ekberg, K., Meyer, C., Scarinci, N., Grenness, C., & Hickson, L. (2014). Disagreements between clients and family members regarding clients’ hearing and rehabilitation within audiology appointments for older adults. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders, 5(2), 217–244. https://doi.org/10.1558/jircd.v5i2.217

- Ekberg, K., Meyer, C., Scarinci, N., Grenness, C., & Hickson, L. (2015). Family member involvement in audiology appointments with older people with hearing impairment. International Journal of Audiology, 54(2), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2014.948218

- Ekberg, K., & Reuber, M. (2015). Can conversation analytic findings help with differential diagnosis in routine seizure clinic interactions? Communication and Medicine, 12(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1558/cam.v12i1.26851

- Elsey, C., Drew, P., Jones, D., Blackburn, D., Wakefield, S., Harkness, K., Venneri, A., & Reuber, M. (2015). Towards diagnostic conversational profiles of patients presenting with dementia or functional memory disorders to memory clinics. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(9), 1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.021

- Erdmann, A. L., Andrade, S. R. D., Mello, A. L. S. F. D., & Drago, L. C. (2013). Secondary health care: Best practices in the health services network. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 21, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692013000700017

- Fasulo, A., Zinken, J., & Zinken, K. (2016). Asking ‘what about’ questions in chronic illness self-management meetings. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(6), 917–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.009

- Fatigante, M., Alby, F., Zucchermaglio, C., & Baruzzo, M. (2016). Formulating treatment recommendation as a logical consequence of the diagnosis in post-surgical oncological visits. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(6), 878–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.02.007

- Fatigante, M., Zucchermaglio, C., & Alby, F. (2021). Being in place: A multimodal analysis of the contribution of the patient’s companion to “first time” oncological visits. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 664747. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.664747

- Forrest, C. B., Majeed, A., Weiner, J. P., Carroll, K., & Bindman, A. B. (2002). Comparison of specialty referral rates in the United Kingdom and the United States: Retrospective cohort analysis. British Medical Journal, 325(7360), 370–371. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7360.370

- Galatolo, R., & Fasulo, A. (2022). Talking down pain in the prosthesis clinic: The emergence of a local preference. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 55(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2022.2026172

- Galatolo, R., & Margutti, P. (2016). Territories of knowledge, professional identities and patients’ participation in specialized visits with a team of practitioners. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(6), 888–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.010

- Gill, V. T. (2019). ’Breast cancer won’t kill ya in the breast’: Broaching a rationale for chemotherapy during the surgical consultation for early-stage breast cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(2), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.09.002

- Golembiewski, E. H., Suarez, N. R. E., Escarria, A. P. M., Yang, A. X., Kunneman, M., Hassett, L. C., & Montori, V. M. (2023). Video-based observation research: A systematic review of studies in outpatient health care settings. Patient Education and Counseling, 106, 42–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2022.09.017

- Gutzmer, K., & Beach, W. A. (2015). “Having an ovary this big is not normal”: Physicians’ use of normal to assess wellness and sickness during oncology interviews. Health Communication, 30(1), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.881176

- Health care. (2020). Health care - Secondary care. New World Encyclopedia. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Health_care&oldid=1035038

- Heritage, J., & Raymond, G. (2005). The terms of agreement: Indexing epistemic authority and subordination in talk-in-interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(1), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800103

- Heritage, J., & Robinson, J. D. (2006). Accounting for the visit. In J. Heritage & D. W. Maynard (Eds.), Communication in medical care: Interaction between primary care physicians and patients (Vol. 20, pp. 48–85). Cambridge University Press.

- Huber, J., Streuli, J. C., Lozankovski, N., Stredele, R. J., Moll, P., Hohenfellner, M., Huber, C. G., Ihrig, A., & Peters, T. (2016). The complex interplay of physician, patient, and spouse in preoperative counseling for radical prostatectomy: A comparative mixed-method analysis of 30 videotaped consultations. Psychooncology, 25(8), 949–956. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4041

- Jenkins, L., Cosgrove, J., Ekberg, K., Kheder, A., Sokhi, D., & Reuber, M. (2015). A brief conversation analytic communication intervention can change history-taking in the seizure clinic. Epilepsy & Behavior, 52(Pt A), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.08.022

- Jenkins, L., & Reuber, M. (2014). A conversation analytic intervention to help neurologists identify diagnostically relevant linguistic features in seizure patients’ talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(3), 266–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.925664

- Jones, D., Drew, P., Elsey, C., Blackburn, D., Wakefield, S., Harkness, K., & Reuber, M. (2016). Conversational assessment in memory clinic encounters: Interactional profiling for differentiating dementia from functional memory disorders. Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1021753

- Jones, D., Wilkinson, R., Jackson, C., & Drew, P. (2020). Interactional variation and non-standardisation in neuropsychological tests: The case of the addenbrooke’s cognitive examination. Qualitative Health Research, 30(3), 458–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319873052

- Lee, S. H., & Sheon, N. (2008). Responsibility and risk: Accounts of reasons for seeking an HIV test. Sociology of Health and Illness, 30(2), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01038.x

- Lehtinen, E. (2005). Information, understanding and the benign order of everyday life in genetic counselling. Sociology of Health & Illness, 27(5), 575–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00457.x

- Lehtinen, E. (2013). Hedging, knowledge and interaction: Doctors’ and clients’ talk about medical information and client experiences in genetic counseling. Patient Education and Counseling, 92(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.005

- Lehtinen, E., & Kääriäinen, H. (2005). Doctor’s expertise and managing discrepant information from other sources in genetic counseling: A conversation analytic perspective. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 14(6), 435–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-005-6453-9

- Mace, S., Collins, S., & Speer, S. (2021). Talking about breast symmetry in the breast cancer clinic: What can we learn from an examination of clinical interaction? Health Expectations, 24(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13144

- Mirheidari, B., Blackburn, D., Harkness, K., Walker, T., Venneri, A., Reuber, M., Christensen, H., & Peña-Casanova, J. (2017). Toward the automation of diagnostic conversation analysis in patients with memory complaints. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 58(2), 373–387. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160507

- Mirheidari, B., Blackburn, D., Reuber, M., Walker, T., & Christensen, H. (2016). Diagnosing people with dementia using automatic conversation analysis [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of Interspeech, San Francisco, CA. ISCA.

- Montori, V. M. (2021). Removing the blindfold: The centrality of care in caring for patients with multiple chronic conditions. Health Services Research, 56(S1), 969–972. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13865

- Monzoni, C. M., Duncan, R., Grünewald, R., & Reuber, M. (2011). How do neurologists discuss functional symptoms with their patients: A conversation analytic study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 71(6), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.09.007

- O’Malley, R., Mirheidari, B., Harkness, K., Reuber, M., Venneri, A., Walker, T., … Blackburn, D. (2021). Fully automated cognitive screening tool based on assessment of speech and language. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 92(1), 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2019-322517

- O’Reilly, M., & Lester, J. N. (2016). The palgrave handbook of adult mental health. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ostermann, A. C. (2021). Women’s (limited) agency over their sexual bodies: Contesting contraceptive recommendations in Brazil. Social Science & Medicine, 290, 114276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114276

- Paré, G., & Kitsiou, S. (2017). Methods for literature review. In F. Lau & C. Kuziemsky (Eds.), Handbook of eHealth evaluation: An evidence-based approach (pp. 151–173). University of Victoria Library Press.

- Parry, R. (2004). Communication during goal-setting in physiotherapy treatment sessions. Clinical Rehabilitation, 18(6), 668–682. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215504cr745oa

- Parry, R. (2024). Communication in palliative care and about end of life: A state-of-the-art literature review of conversation-analytic. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 57(1), 127–148.

- Parry, R., & Land, V. (2013). Systematically reviewing and synthesizing evidence from conversation analytic and related discursive research to inform healthcare communication practice and policy: An illustrated guide. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-69

- Peel, E. (2015). Diagnostic communication in the memory clinic: A conversation analytic perspective. Aging & Mental Health, 19(12), 1123–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.1003289

- Peräkylä, A. (1993). Invoking a hostile world: Discussing the patient’s future in AIDS counselling. Text, 13(2), 291–316.

- Peräkylä, A. (2019). Conversation analysis and psychotherapy: Identifying transformative sequences. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 52(3), 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1631044

- Peräkylä, A., & Bor, R. (1990). Interactional problems of addressing ‘dreaded issues’ in HIV-counselling. AIDS Care, 2(4), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540129008257748

- Peräkylä, A., & Silverman, D. (1991). Reinterpreting speech-exchange systems: Communication formats in AIDS counselling. Sociology, 25(4), 627–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038591025004005

- Pevy, N., Christensen, H., Walker, T., & Reuber, M. (2021). Feasibility of using an automated analysis of formulation effort in patients’ spoken seizure descriptions in the differential diagnosis of epileptic and nonepileptic seizures. Seizure, 91, 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2021.06.009

- Pichonnaz, D., Staffoni, L., Greppin-Bécherraz, C., Menia-Knutti, I., & Schoeb, V. (2021). “You should maybe work together a little bit”: Formulating requests in interprofessional interactions. Qualitative Health Research, 31(6), 1094–1104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732321991508

- Pilnick, A. (2002). ‘There are no rights and wrongs in these situations’: Identifying interactional difficulties in genetic counselling. Sociology of Health and Illness, 24(1), 66–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.00004

- Pilnick, A., & Zayts, O. (2012). ‘Let’s have it tested first’: Choice and circumstances in decision-making following positive antenatal screening in Hong Kong. Sociology of Health & Illness, 34(2), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01425.x

- Pilnick, A., & Zayts, O. (2014). “It’s just a liklihood”: Uncertainity as topic and resource in conveying “positive” results in an antenatal screening clinic. Symbolic Interaction, 37(2), 187–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.99

- Pilnick, A., & Zayts, O. (2016). Advice, authority and autonomy in shared decision-making in antenatal screening: The importance of context. Sociology of Health & Illness, 38(3), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12346

- Pilnick, A., & Zayts, O. (2019). The power of suggestion: Examining the impact of presence or absence of shared first language in the antenatal clinic. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(6), 1120–1137. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12888

- Pinto Júnior, V. C., Cavalcante, R. C., Branco, K. M. P. C., Cavalcante, C. T. D. M. B., Maia, I. C. L., Souza, N. M. G. D., … Carvalho Junior, W. (2016). Proposal of an integrated health care network system for patients with congenital heart defects. Brazilian Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery, 31, 256–260. https://doi.org/10.5935/1678-9741.20160056

- Plug, L., Sharrack, B., & Reuber, M. (2009). Conversation analysis can help to distinguish between epilepsy and non-epileptic seizure disorders: A case comparison. Seizure, 18(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2008.06.002

- Reuber, M., Blackburn, D., Elsey, C., Wakefield, S., Ardern, K., Harkness, K., Venneri, A., Jones, D., Shaw, C., & Drew, P. (2018). An interactional profile to assist the differential diagnosis of neurodegenerative and functional memory disorders. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 32(3), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0000000000000231

- Reuber, M., Toerien, M., Shaw, R., & Duncan, R. (2015). Delivering patient choice in clinical practice: A conversation analytic study of communication practices used in neurology clinics to involve patients in decision-making. Health Services and Delivery Research, 3(7), 1–170. https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr03070

- Ringberg, U., Fleten, N., Deraas, T. S., Hasvold, T., & Førde, O. (2013). High referral rates to secondary care by general practitioners in Norway are associated with GPs’ gender and specialist qualifications in family medicine, a study of 4350 consultations. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-147

- Robson, C., Drew, P., & Reuber, M. (2016). The role of companions in outpatient seizure clinic interactions: A pilot study. Epilepsy & Behavior, 60, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.04.010

- Robson, C., Drew, P., Walker, T., & Reuber, M. (2012). Catastrophising and normalising in patient’s accounts of their seizure experinces. Seizure, 21, 795–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2012.09.007

- Royal College of Physicians. (2018). Outpatients: The future - adding value through sustainability.

- Ruusuvuori, J., Aaltonen, T., Lonka, E., Salmenlinna, I., & Laakso, M. (2020). Discussing hearing aid rehabilitation at the hearing clinic: Patient involvement in deciding upon the need for a hearing aid. Health Communication, 35(9), 1146–1161. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1620410

- Schoeb, V. (2009). “The goal is to be more flexible”–Detailed analysis of goal setting in physiotherapy using a conversation analytic approach. Manual Therapy, 14(6), 665–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2009.02.004

- Schoeb, V., Staffoni, L., Parry, R., & Pilnick, A. (2014). “What do you expect from physiotherapy?”: A detailed analysis of goal setting in physiotherapy. Disabil Rehabil, 36(20), 1679–1686. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.867369

- Schöpf, A. C., Martin, G. S., & Keating, M. A. (2017). Humor as a communication strategy in provider-patient communication in a chronic care setting. Qualitative Health Research, 27(3), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315620773

- Schwabe, M., Howell, S., & Reuber, M. (2007). Differential diagnosis of seizure disorders: A conversation analytic approach. Social Science and Medicine, 65(4), 712–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.045

- Sheon, N., & Lee, S. H. (2009). Sero-skeptics: Discussions between test counselors and their clients about sexual partner HIV status disclosure. AIDS Care, 21(2), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120801932181

- Silverman, D., & Bor, R. (1991). The delicacy of describing sexual partners in HIV-test counselling: Implications for practice. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 4(2–3), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515079108256721

- Silverman, D., & Peräkylä, A. (1990). AIDS counselling: The interactional organisation of talk about ‘delicate’ issues. Sociology of Health & Illness, 12(3), 293–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11347251

- Sterponi, L., Zucchermaglio, C., Fantasia, V., Fatigante, M., & Alby, F. (2021). A room of one’s own: Moments of mutual disengagement between doctor and patient in the oncology visit. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(5), 1116–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.10.024

- Stevanovic, M., & Peräkylä, A. (2012). Deontic authority in interaction: The right to announce, propose, and decide. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(3), 297–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.699260

- Stevanovic, M., & Peräkylä, A. (2014). Three orders in the organization of human action: On the interface between knowledge, power, and emotion in interaction and social relations. Language in Society, 43(2), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404514000037

- Suchman, A. L., Markakis, K., Beckman, H. B., & Frankel, R. (1997). A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 277(8), 678–682. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540320082047

- Tapsell, L. C., Brenninger, V., & Barnard, J. (2000). Applying conversation analysis to foster accurate reporting in the diet history interview. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100(7), 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00237-6

- Tate, A. (2019). Treatment recommendations in oncology visits: Implications for patient agency and physician authority. Health Communication, 34(13), 1597–1607. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1514683

- Tate, A. (2020). Invoking death: How oncologists discuss a deadly outcome. Social Science & Medicine, 246, 112672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112672

- Tate, A., & Rimel, B. J. (2020). The duality of option-listing in cancer care. Patient Education and Counseling, 103(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.025

- Toerien, M. (2021). When do patients exercise their right to refuse treatment? A conversation analytic study of decision-making trajectories in UK neurology outpatient consultations. Social Science & Medicine, 290, 114278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114278

- Toerien, M., Jackson, C., & Reuber, M. (2020). The normativity of medical tests: Test ordering as a routine activity in “new problem” consultations in secondary care. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(4), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1785768

- Toerien, M., Shaw, R., Duncan, R., & Reuber, M. (2011). Offering patients choices: A pilot study of interactions in the seizure clinic. Epilepsy & Behavior, 20(2), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.11.004

- Toerien, M., Shaw, R., & Reuber, M. (2013). Initiating decision-making in neurology consultations: ‘recommending’ versus ‘option-listing’ and the implications for medical authority. Sociology of Health & Illness, 35(6), 873–890. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12000

- Webb, H. (2009). ‘I’ve put weight on cos I’ve bin inactive, cos I’ve ‘ad me knee done’: Moral work in the obesity clinic. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31(6), 854–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01188.x

- Weiste, E. (2016). Formulations in occupational therapy: Managing talk about psychiatric outpatients’ emotional states. Journal of Pragmatics, 105, 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.08.007

- Wessels, T. M., Koole, T., & Penn, C. (2015). ‘And then you can decide’–antenatal foetal diagnosis decision making in South Africa. Health Expect, 18(6), 3313–3324. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12322

- WHO. (2000). The world health report 2000: Health systems: Improving performance. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42281

- WHO. (2016). Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Zhao, C., & Ma, W. (2020). Patient resistance towards clinicians’ diagnostic test-taking advice and its management in Chinese outpatient clinic interaction. Social Science & Medicine, 258, 113041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113041