ABSTRACT

This article investigates opera performers’ ideas on what they can do on stage to music in the service of portraying the characters of an opera production. The performers both describe and depict their ideas, that is, tell and show them, in proposals. Using multimodal interaction analysis, the article examines how the relative deployment of depictions and descriptions in performer proposals change over time. During joint decision-making micro-histories, the proposals become increasingly depictive, as displayed access, alignment, and agreement with the ideas increase. If ideas originate in previous instructions and decisions, however, proposals are immediately constructed with depictions, and if ideas are resisted, they are never fully depicted. The article thus reveals the dialogical and interactional development of ideas on their way to materialize as artwork. The data consist of 20 hours of video recorded opera rehearsals in Swedish, English, and some Italian, which is the language of the libretto.

In scenic opera rehearsals, the ensemble creates movements, postures, and facial expressions that the performers can deploy to portray their characters’ behaviors and emotions. The director of the opera production studied in this article characterizes the aim of scenic opera rehearsals as a pursuit of bodies to suit the music. These performance bodies, as they will be referred toFootnote1—that is, the assemblages of multimodal resources that participants use to portray their characters—must meet requirements such as coherency with the developing aesthetics of the production, feasibility in terms of singing in different physiological and material circumstances, and psychological realism. The process of reaching satisfactory performance bodies is one of decision making (cf. Stevanovic, Citation2012), and in this particular setting this process is joint and based on performer ideas, as opposed to, for example the director making decisions that are communicated via instructions (see Löfgren, Citation2023a, for the distribution of deontic rights in these rehearsals).

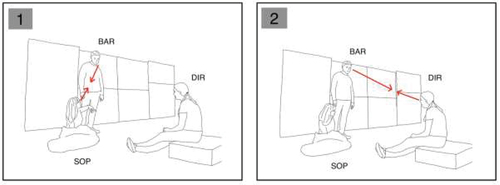

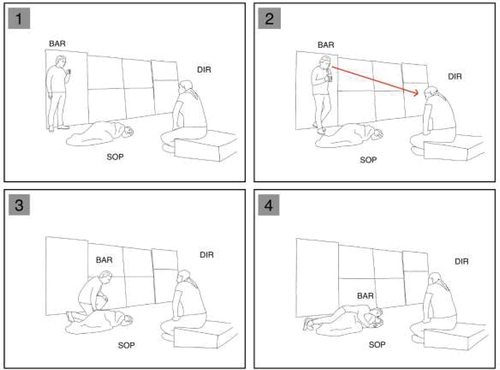

Figure 1a. (image 1–2). (1) The baritone responds to the soprano’s question while gazing at her. (2) The baritone makes the proposal while gazing at the director.

Figure 1b. (image 1–4). (1) The director elicits a proposal from the baritone. (2) The baritone makes a proposal while relocating to depict (3) The baritone requests agreement from the director. (4) The baritone lies down next to the soprano.

Figure 1c. (image 1–4). (1) The baritone accounts for an upcoming proposal. (2) The baritone moves toward the soprano but halts and self-repairs to check alignment. (3) The baritone continues to move toward the floor after the director’s displayed alignment. (4) The baritone lies down.

Performance bodies thus develop in decision-making processes between performers, director, and assistant director. This article conceives of these processes as interactional micro-histories—that is, shared lived experiences beyond single sequences but nevertheless relatively close in time, such as minutes apart (Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023). To create the performance bodies, the participants deploy the interactional practices of description and depiction (Clark, Citation2016, Citation2019)—that is, describing the performance body with words, or showing it with sounds and body movements (see also Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2022). To give an example of what this distinction looks like in opera rehearsals, a performer may describe an idea for a performance body by saying, “I could lie down next to you and sing,” while standing still and gazing at the director and coperformer. The performer may also propose the same idea through a depiction in which the performer actually lies down next to the coperformer while singing.

Focusing on performer proposals of performance bodies, the article shows how the relevance of the two basic interactional practices of description and depiction in opera rehearsals is related to aspects of the joint decision-making process. Over decision-making micro-histories, performer proposals that express the same idea, such as, for instance, “lying down next to a coperformer in a certain scene,” become increasingly depictive if the recipients respond to them in positive ways. When an idea is introduced, it is only described to assure a preliminary epistemic access (Stevanovic, Citation2012; see also Stivers et al., Citation2011) to it. If there is alignment (Stivers, Citation2008) and agreement (Stevanovic, Citation2012) with the described idea—that is, the recipients cooperate to assure further access to the idea and express that they think is suitable for the production—the performers move on to depict it in reduced versions simultaneous to descriptions, and in subsequent iterations in complete forms—that is, with both visuospatial and vocal/aural resources.

The article continues to explore how depictions are deployed in proposals as a practice for joint decision making in opera rehearsals (see also Löfgren, Citation2023a; Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023). By documenting the decision-making micro-histories of specific ideas, it will be demonstrated how the production gradually approaches its presentable and seeable form in paradoxically individual and collective processes.

Background

Depictions and descriptions

This article draws on Clark’s (Citation1996), Clark (Citation2016, Citation2019) distinction between the communicative strategiesFootnote2 of depiction and description. Depiction is based on iconicity, which means that the relationship between the sign and the referent is one of similarity. Description, on the other hand, evokes an arbitrary and conventionally established link between the sign and the referent (Clark, Citation1996, Citation2016).

In this article, depiction is deployed as an umbrella term encompassing different types of iconic practices in interaction (see also Löfgren, Citation2023a; Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2022, for similar uses of the term depiction), such as demonstrations (Heath, Citation2002; Keevallik, Citation2010, Citation2013a, Citation2014a), (re)enactments (Ehmer & Mandel, Citation2021; Sidnell, Citation2006), reported speech (Günthner, Citation1999; Holt & Clift, Citation2007), iconic gestures (Schegloff, Citation1984; Urbanik & Svennevig, Citation2021), and animations (Cantarutti, Citation2021, Citation2022). The term description is used to denote lexicosyntactic practices (cf. Clark, Citation1996, Citation2016). More precisely, it has been suggested that description is a practice that relies on lexical semantics, as opposed to depiction that relies on perceptive meaning (see discussion in Löfgren, Citation2023b; see also Clark, Citation2016). Although interactional research papers have not targeted descriptions per se, descriptions are often discussed in relation to depictions, as lexicosyntactic practices that specify the meaning of depictions. Schegloff (Citation1984) spoke of the lexical affiliate of depictive gestures, Thompson and Suzuki (Citation2014) of narration (description) vs. enactment (depiction) as two different strategies that participants deploy in storytelling, and Schmidt and Deppermann (Citation2022) about showing and telling in instructions during theater rehearsals.

Depictions, on the other hand, have been more widely studied in interactional research. For instance, they are frequently deployed in creative pedagogical environments—that is, settings in which participants learn bodily artistic practices such as dance (Keevallik, Citation2010), musical instruments (Stevanovic, Citation2021; Stevanovic & Frick, Citation2014), classical singing (Szczepek Reed, Citation2021), and orchestral conducting (Sunakawa, Citation2018). In these settings, depictions (often referred to as demonstrations)Footnote3 are used to exemplify and model instructions that the learners should incorporate in their bodily artistic practices; or by the learners to transform claims of understanding into demonstrations of understanding (Sunakawa, Citation2018). Depictions are used for similar purposes in settings in which performing arts are created, by both director/conductor and performers, to instruct and propose (Löfgren, Citation2023a; Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2022; Veronesi, Citation2014; Weeks, Citation1996). Furthermore, in more informal settings, it has been shown that depictions can serve as candidate understandings of prior ideas and proposals of new ones (Balantani, Citation2022; Due, Citation2016; Yasui, Citation2013). Building on these strands of previous research, the present article investigates when, and during which interactional circumstances, depictions are deployed in joint decision-making micro-histories of an opera ensemble.

Depictions represent a scene in a “there-and-then” that can be distinguished from the here-and-now of the interaction (cf., Löfgren, Citation2023a). This distinction is achieved through the deployment of various multimodal resources over time (Cantarutti, Citation2021, Citation2022; Ehmer & Mandel, Citation2021; Sidnell, Citation2006). Depictions can be either vocal/aural or visuospatial (Löfgren, Citation2023a), but they often involve both modalities (Cantarutti, Citation2021; Ehmer & Mandel, Citation2021; Sidnell, Citation2006).Footnote4 Visuospatial arrangements of depictions are often realized before vocal/aural (Ehmer & Mandel, Citation2021), and visuospatial depictions may occur simultaneously to vocal/aural descriptions (Löfgren, Citation2023a; Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023). This article shows how the multimodal complexity of depictions increases over decision-making micro-histories.

It has been argued that depictions require “interpretative frameworks” to be correctly understood (Clark, Citation2019, p. 252). Both common ground (Clark, Citation1996) and linguistic resources in the sequential environment may be an important part of such a framework (Schegloff, Citation1984; see also Stevanovic & Frick, Citation2014; Weeks, Citation1996). On the other hand, depictions may facilitate the understanding of descriptions when the target of an instruction is embodied behavior (Evans & Lindwall, Citation2020; Sunakawa, Citation2018; Urbanik & Svennevig, Citation2021). Depictions and descriptions are thus not to be considered translation of one another (see Löfgren, Citation2023b). In this article, it will be shown that depictions are used when there is an interpretative framework available—that is, preliminary epistemic access to the idea via previous descriptions in the interactional micro-history. In addition, however, depictions secure better access to that same idea and are oriented to as crucial for the decision making. Depictions and descriptions thus mutually elaborate each another in the decision-making micro-history. To provide a background for the micro-histories that are dealt with in this article, the next two sections present previous research on interactional histories (“Interactional histories”) and joint decision making (“Proposals and joint decision-making”).

Interactional histories

Interactional histories, or shared lived experiences beyond the immediate interactional sequence, have been shown to influence how participants in interaction design their turns-at-talk (Deppermann, Citation2018). Turns become shorter, more indexical, syntactically less complex, and even more infrequent over time as recipients develop skills in instructional settings (Broth et al., Citation2017; Deppermann, Citation2018; Keevallik, Citation2020; Stukenbrock, Citation2021).

This article is interested in how shared interactional history influences performer proposals during opera rehearsals. It builds on previous work on theater rehearsals that shows how participants collaboratively carve out the details of theatrical scenes over time (Hazel, Citation2018; Lefebvre, Citation2018; Norrthon, Citation2019). As in instructional settings, it has been shown that the interaction of theater rehearsals is characterized by a move from descriptions to depictions (from verbal to visual practices) of what to do on stage (Norrthon & Schmidt, Citation2023; see also Deppermann & Schmidt, Citation2021; Lefebvre & Mondada, Citation2023; Norrthon, Citation2019, Citation2021; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023). In contrast to an earlier focus on director instructions and performer implementations, this article concentrates on performer ideas for performance bodies and how they materialize in series of proposals. Although implementations of director instructions, indeed, constitute a way for performers to make proposals (see Norrthon & Schmidt, Citation2023; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023; see also Lefebvre, Citation2018 on “candidate interpretations”), this article specifically focuses on when performers actively, and agentively, request to influence the local interactional agenda by evoking their own ideas in proposal turns that introduce the normative constraint of an uptake of the proposal. The next section zooms in on the characteristics of proposals and the processes they initiate—joint decision making.

Proposals and joint decision making

Proposals differ from instructions in that they invoke a weaker deontic stance (Stevanovic & Peräkylä, Citation2014). When making proposals, participants do not assume that they themselves can make the ultimate decision. Instead, they open a process of joint decision making (see Houtkoop, Citation1987; Lindström, Citation2017; Stevanovic, Citation2012). The depictions, and descriptions, of ideas in the performers’ proposals serve as the ground for joint decision making on performance bodies.

Stevanovic (Citation2012) showed three necessary components in the process of reaching a joint, rather than unilateral, decision: (1) access to the content of a proposal, (2) agreement with the feasibility of the proposal, and (3) commitment to the future action that the proposal targets.Footnote5 In addition to access and agreement, previous research on opera rehearsals has shown how alignment with proposals facilitate the joint decision-making process as they allow the other participants to develop their ideas for the performance (Löfgren, Citation2023a). Alignment is understood as a structural compliance with the sequence as it unfolds that is relatively independent of affiliation with emotional stance (see Stivers, Citation2008). During opera rehearsals, the director may, for instance, align by positioning her- or herself as a spectator to a proposal depiction or produce continuers that allow a participant to pursue a proposal description, although he or she may display (mild) disagreement with the idea as such. In the rehearsals, recipient alignment is a crucial component of the depictions, as the latter require similar suspensions of the normal turn-taking patterns that are evident in storytelling (see Stivers, Citation2008). In this article, it is shown that ideas on performance bodies are depicted when there is displayed (preliminary) access to them, alignment, and ultimately agreement on their suitability for this opera production.

Previous research has shown that the content of proposals may be subject to development with recipient uptake so that the outcome of the proposal sequence differs somewhat from the idea that is originally proposed (Due, Citation2016; Mondada, Citation2015; Yasui, Citation2013). This joint achievement of the idea may take entirely visuospatial forms, in which depictions are implicitly modified through depictions rather than explicitly challenged through rejections (cf., Due, Citation2016; Yasui, Citation2013). The present article continues to explore the dialogical nature of ideas in joint decision-making processes, by focusing specifically on depictions as a tool in the process, and their relationship to descriptions.

Method and material

The method of this study is multimodal interaction analysis (Broth & Keevallik, Citation2020), grounded in ethnomethodological conversation analysis (see Sidnell, Citation2006). This method allows for a detailed sequential scrutiny of how participants deploy depictions and descriptions in the pursuit of performance bodies. The analysis is informed by previous longitudinal studies of interactional histories that examine changes in turn design over time (cf., Deppermann, Citation2018; Deppermann & Pekarek Doehler, Citation2021). Although work on interactional histories may span over years (cf., for instance, Mondada, Citation2018a) or months (cf., for instance, Hazel, Citation2018), recent work by Schmidt and Deppermann (Citation2023) focuses on a “micro-history” of seven minutes. Following Schmidt and Deppermann (Citation2023, p. 275) and their approach to micro-histories as “a collection of chronologically ordered instances of executions of the same activity or task by (roughly) the same participants,” this article analyzes executions of the same idea that is being proposed through several steps over micro-histories of 10 to 20 minutes.

The material consists of 20 hours of video recorded scenic opera rehearsals from a Swedish opera production. Participants in the data are the director, assistant director, and soloist singer performers. The participants gave informed consent for video recording and for the material to be used in research publications. For de-identification purposes, personal names of the participants have been pseudonymized. The languages spoken during the rehearsals are Swedish and English. Occasional Italian words and phrases occur, as it is the language of the libretto of the performance. The opera centers around a father (sung by a baritone) and his daughter (soprano). Tragically, the daughter gets murdered at the end of the opera, to the father’s ineluctable despair.

The material was transcribed according to the transcription conventions developed by Jefferson (Citation2004) and Mondada (Citation2018b). Song was indicated using ♪. The analysis draws on a collection of 36 distinct performer ideas. In turn, these ideas are expressed between one to five times in a consecutive manner. For instance, the idea that a performer can lie down next to their coperformer in a scene, may be expressed during one point of a discussion of that scene, to then be expressed again two or several more times some five to 10 minutes later. The analysis focuses on how the design of the turns—that is, the proposals, that express the ideas develop over joint decision-making micro-histories.

Analysis

In the analysis, it will be shown how performers propose ideas for performance bodies in increasingly depictive forms over time as the director displays access to and alignment and agreement with them. Section 4.1 of the analysis reveals a pattern (n = 16 out of the total 36 cases in the collection) of how performers bring up new ideas for performance bodies, and how these ideas are then expressed again several times over the course of 10 to 20 minutes. The section demonstrates how ideas move through different phases. At first, ideas are only described and not, or only minimally, depicted. In subsequent iterations ideas are described and depicted with visuospatial resources (quasi-)simultaneously. Even later, the ideas are depicted with both visuospatial and vocal/aural resources and only minimally, or not at all, described.

Thereafter, section 4.2 shows variations from this pattern. When ideas originate in previous ideas and arrangements—that is, they are not entirely new ideas that the performers initiate but are highly dependent on previous instructions from the director or joint decisions—the performers immediately depict their ideas, rather than describing them first. It is argued that in these cases, (at least partial) access to the idea is implied (n = 10/36). On the other hand, ideas, whether initiated by the performer in question or others, may be abandoned or modified due to recipient resistance (n = 7/36).Footnote6 These two alternative micro-histories, that do not entirely follow the three-phase pattern of (1) description only, (2) description + depiction, and (3) depiction only are illustrated through one and the same case. Consequently, the decision-making micro-history of two individual ideas is presented: lying down next to a coperformer when her character is dying (4.1) and not addressing one’s coperformer on a specific libretto line (4.2).

From description to depiction over a joint decision-making micro-history

This section shows how performers move from describing to depicting their ideas over joint decision-making micro-histories. The performers begin by describing ideas before depicting and describing them (quasi-)simultaneously, and then finally depicting them with both visuospatial and vocal/aural resources, and with no or minimal simultaneous descriptions. The movement from description to depiction reflects the progress of the joint decision-making process. Depictions, especially full-fledged forms (i.e., complex depictions involving both the vocal/aural and visuospatial modalities), occur in later stages of the decision-making micro-history, as the director increasingly displays access to and alignment and agreement with the proposed ideas. Out of the total 36 micro-histories of ideas in the collection, 16 follow this developmental pattern. One of these, , is chosen to illustrate the phenomenon. The idea in question is that the baritone (father) should lie down next to the soprano (daughter) while the soprano’s character is dying in a sack on the floor.

presents the first time the baritone (BAR) expresses the idea of lying down next to the soprano (SOP). Right before the extract, the baritone has concluded that it might not be of benefit to rehearse this scene now, as the costume, which will imply physical constraints for the baritone as it consists of a corset and a hunchback prothesis, is still in manufacture. The soprano then asks him to imagine what would be the best position for him to sing in if he would be wearing his costume (lines 1–4). The extract also features the director (DIR) and an opera student who is only minimally involved in the interaction (see Extract l. 2). The focus of the analysis is the baritone’s proposal (lines 6–7).

The soprano first asks a wh-question on what the baritone thinks is the best position if he would be wearing the costume (lines 1–3), but she immediately adds a polar question in which she provides an idea herself, that he can sit on his knees (line 4). After a pause (line 5), the baritone responds by recycling parts of the soprano’s utterance: på knä e de bästa sättet (“on the knees is the best way,” line 6), in what first seems to be a positive uptake of the soprano’s proposed idea. In a coordinated clause, however, prefaced by eller (“or”), he introduces an alternative idea through a description: that he can lie down next to the soprano and sing (lines 6–7).

After a pause, he assesses his own idea de tycker ja skulle va fint (“that I think would be nice”), while addressing the director through gaze (line 9, see ). The assessment provides an aesthetic account for the idea. Addressing it to the director, rather than to the soprano whose question he just answered, indexes the involvement of the director in the decision-making process. It serves to elicit a confirmation from the director that displays her access to the baritone’s idea so far.

The baritone has remained still throughout his proposal and account (lines 6–9), and his speech contains no origo displacement indicative of depictive speech (see Löfgren, Citation2023a, on the notion of depictive speech and its relationship to origo). Thus, the idea of lying down next to the soprano has only been described, and not depicted.

The director subsequently responds by a confirmation token aa (“yes”). The prosodic design (low pitch, curved intonation), indexes receipt (and thereby preliminary access), a mild challenge, and an encouragement to continue, rather than being affirmative and accepting the proposal (cf., Lindström, Citation2009). Indeed, the confirmation token is immediately followed by a request that the baritone show her his idea (line 10). Interestingly, this is precisely expressed as “show me” (rather than an impersonal construction), which indexes the director’s influence over the decision making. The request shows that the director does not yet have sufficient access to be able to commit to the idea by, for instance, explicitly requesting the performers to use this proposed performance body on stage in the future (cf., Stevanovic, Citation2012). Simultaneously, however, it demonstrates the director’s alignment with the baritone’s pursuit of the idea (in contrast to an explicit rejection or modification). In response, the baritone gets down on the floor next to the soprano and gets ready to depict the idea.

In this first extract we have thus seen how the baritone describes an idea. The description serves to assure (at least minimal) epistemic access and alignment (cf., Stivers et al., Citation2011). Merely describing the idea, however, does not provide sufficient access, and the baritone is requested to depict his idea. In , the baritone adds a depiction simultaneously to his description of the idea.

occurs a couple of minutes after . After , the baritone did not depict his idea despite the director’s request. Instead, the participants began to speak about suitable positions for the soprano. In the beginning of , the baritone is seated next to the soprano, who is lying on the floor in the sack. They have just adjusted the position of the soprano’s head: on the ground rather than on the baritone’s lap. The director then elicits a proposal from the baritone (“Simon”)Footnote7 on what he can do at that point, by recycling his idea of lying down from earlier (, lines 1–2). The idea is then repeated by the baritone, now with vocal/aural descriptions and visuospatial depictions (lines 6–10).

As the soprano in , the director immediately provides an idea herself after her question to the baritone (lines 1–2)—namely, that the baritone should lie down next to the soprano, which is what he himself has proposed earlier (see ). This displays the director’s access to the baritone’s idea. However, the intonation curve and wording choices då (“then”), as well as the final eller (“or”), indicate that there is not yet agreement on whether the idea is suitable.

In response, the baritone provides an account for the idea (his character must be in a total state of panic and has no time to ruminate on how to sit, lines 3–5), followed by a description of the idea in a proposal (lines 6–10), coupled with a request for agreement (lines 8, 10). During the account and proposal (lines 3–10), the baritone gets on all fours next to the soprano, moves closer to her and puts his hands next to her, in preparation for a depiction (see ). When requesting agreement (lines 8, 10), however, he halts his movements and gazes at the director. By doing so, he precisely orients to the fact that there is still no agreement on whether the idea is suitable. The director responds affirmatively and thereby agrees with the suitability of the idea, and once again urges the baritone to depict it (line 11).

In this extract, we have seen how the baritone proposes the idea that he can lie down next to the soprano a second time by describing and depicting it (quasi)-simultaneously, in contrast to , in which the idea was only described. The director displays access to the idea by preemptively formulating it herself, agrees by confirming the suitability of the idea, and aligns by urging the baritone to depict it. The baritone orients to the need for (at least preliminary) agreement before fully realizing his depiction. In turn, depictions increase access to the idea, and the director orients to depictions as crucial in the creative decision-making process.

Although the baritone has depicted the idea in , he has not coordinated it with the song it is supposed to suit. A couple of minutes later, however, after a discussion on another topic, the baritone proposes the idea once more, this time by mobilizing both the visuospatial and vocal/aural modalities toward the depiction, while no longer describing it. In the beginning of , the baritone is standing next to the soprano, who is still on the floor. Right before the extract, the baritone recites two lines from the libretto: Gilda mia Gilda, and the director instructs the baritone to shake the soprano on those lines. In overlap with the director’s instruction, the baritone initiates an account for an upcoming proposal (line 1).

On lines 1–5, the baritone argues that because the song is slow and produced in a near-spoken manner (parlando), they (i.e., the baritone and the director as well as the future hypothetical audience) must have understood something. At this point, due to prior conversations on the topic (not shown here), exactly what they understand is not explicitly stated. This serves as a preemptive account to a turn that projects a proposal and that is tied to the account by means of the causal connective så (“so”), så här skulle jag (“so here I could,” line 11).

While producing the account on lines 1–5, the baritone starts to walk toward the soprano, a relocation that projects a depiction (cf., Löfgren, Citation2023a). Before finishing the turn that projects a proposal, however, he self-repairs and inserts a conditional clause om man nu ska ha det här (“if one now should have that here,” lines 11–13, see ) while shifting his gaze direction toward the director and decelerating his speed of walking toward the soprano. This constitutes an indexical way of checking whether the director aligns with a depiction of an idea, before depicting it.Footnote8

As the director immediately urges him to continue in overlap (line 12), the baritone continues toward the soprano while resuming the proposal här skulle man liksom (“here one should like,” line 13). Through prosodic stress on här (“here”), he puts emphasis on the placement of the idea within the libretto, that is, its precise coordination with the libretto line Gilda mia Gilda.

The syntax of the utterance on line 13 projects a verb, but instead, the baritone begins to recite libretto lines while slowly lying down next to the soprano (lines 14–15; cf., Keevallik, Citation2013b, Citation2014b, Citation2018). In contrast to Extracts 1a–b, there is thus no description of the idea, such as, “here one could lie down next to her while singing.” Due to previous interactional micro-history, the baritone does not need to describe his idea again, but access to it is now assumed.

On line 16, the director displays both access to and agreement with the idea and the argument that supports it—that the daughter is dead (which is what the audience “understands” by then, line 2), and that because she is dead, the idea to lie down next to her when he says those lines is suitable. Thereafter, the baritone tries to sing in the position (lines omitted), before once again lying still next to the soprano and saying å så bara så (“and then just like that,” line 17). After a pause (line 18), the director displays agreement again by positively assessing the idea by saying ja (“yes”) with emphasis (line 19).

In , the analysis has illustrated a common trajectory (n = 16/36 cases) for how performers propose their own ideas for performance bodies. We have seen how a performer expresses his idea in three distinct proposal turns within the time frame of roughly 10 minutes. Over time, and as the director displays increased epistemic access to and alignment and agreement with the idea, the proposal turns become increasingly depictive and decreasingly descriptive (cf., Broth et al., Citation2017; Deppermann, Citation2018). When first introduced, the idea is only described. When the idea gets expressed once again a few minutes later, it is depicted with visuospatial resources and described with vocal/aural resources. Another couple of minutes later, when the director has displayed access to the idea by proposing it herself, alignment by urging the baritone to depict it, and finally agreement that the idea is suitable, the baritone depicts the idea with both visuospatial and vocal/aural resources, and the performance body thus becomes accompanied by the music it is intended to suit.

Over the course of the relatively short time spans of these joint decision-making micro-histories, performers do interactional work to assure that the other participants are involved in the decision making by assuring access, alignment, and agreement to ideas. In this way, ideas are gradually introduced, and although they originate with one performer and do not get modified by other performers, the other participants are implied in the expression of the idea in several steps of its development. The decision making is inherently joint (cf., Stevanovic, Citation2012). The next section will elaborate on the joint, dialogical nature of scenic opera rehearsals by demonstrating cases when other participants become more directly involved in the development of ideas.

Alternative decision-making micro-histories: joint development of ideas

This section shows how other participants (director or other performers) may influence a performer’s ideas, both before and after they have been proposed, and how this influence may alternate the pattern of moving from description to depiction described in section 4.1. Two different variations of this basic pattern will be described. First, ideas may originate in, or align with, previous ideas and arrangements (10 cases out of the 36 in the collection). These ideas and arrangements may be earlier decisions, or as in below, or director instructions that performers then exploit to make proposals. In these cases, the initial stage in which ideas are described but not depicted, can be bypassed when performers make their proposals, as there already is (some) access to the content of the proposal, and alignment and agreement with is (sometimes wrongly) inferred from previous stances. In contrast to the pattern shown in Extract 4.1, these ideas do not originate with performers but are being developed by them.

Furthermore, ideas can also be abandoned or modified due to recipient resistance (n = 7/36). In these cases, the performer does not move from simultaneous description and depiction to full-fledged depiction on his own, but in concert with the other participants (or not at all, depending on how disaligning and disagreeing the responses are). In the interest of saving space, these two different variations will be illustrated with one and the same example in which they both occur.

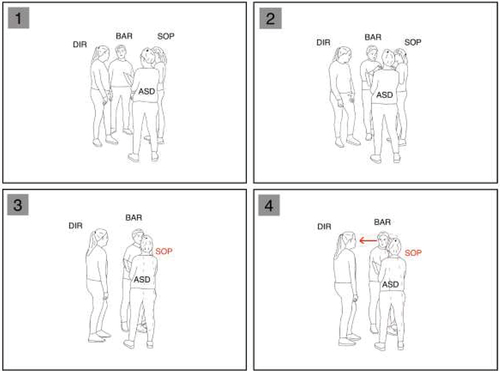

In the extract below, the idea in focus is that the baritone should not address the soprano on a particular libretto line (piangi “cry”).Footnote9 The director is giving an instruction to the baritone on what he should do on some libretto lines that occur prior to piangi—that is, solo per me l’infamia (“only mine, the disgrace”). In the end, she instructs him not to “speak to the soprano at all” (line 01), when singing solo per me l’infamia. Building on that instruction, the baritone then proposes that he should not address the soprano on piangi either (lines 12–15). The extract also features the soprano and the assistant director (ASD).

After having recounted what he previously did on the subsequent line piangi (i.e. addressing the soprano, lines 9, 11), the baritone now proposes an idea that contrasts with that, to extend the director’s idea of not addressing the soprano on solo per me l’infamia, to piangi as well (lines 12–15). The causality markers så därför egentligen (“so that’s why really”) serves to index that this idea aligns with the director’s instruction just prior (line 5).

The proposal is constructed as a description that is intermeshed with a depiction (cf., Clark, Citation2016 on embedded depictions; see also Keevallik, Citation2018 on syntactic-bodily units). After projecting a verb (line 13), the baritone instead starts to sing the word piangi while slowly releasing the soprano and gazing toward the ceiling (lines 12–13, see ). He then syntactically recompletes the turn with a description, ba släpper (“just releases,” line 15).

In contrast to the pattern in , in which the baritone describes an idea to assure access and alignment before a depiction, the baritone here draws on a descriptive instruction from the director (line 1), when he makes a proposal. The fact that there already is partial access to the idea (not addressing the soprano), as it is an extension of the director’s idea just prior, allows for the baritone to move into a depiction already the first time he himself proposes (an extension of) the idea, although the depiction is reduced in form and occurs simultaneously to descriptions (cf. above). The baritone’s proposal simultaneously displays understanding of the director’s instruction just prior, and of the developing aesthetics of the performance. By still providing descriptions of the idea (in contrast to the latest stage in section 4.1, ), the baritone draws attention to the aspect of his depiction that the director should now evaluate: the mere releasing of the soprano.

The extract below uncovers the director’s uptake of the idea, which involves a slight modification of it. The extract occurs a couple of minutes later than , after a parenthetical sequence on exactly how the baritone should embrace the soprano. The director has now moved closer to the acting couple and has positioned her hands on the baritone’s right arm (see , image 1). Right before the extract, she requests that the baritone starts to sing his last line before piangi, which he does on line 1.

Figure 2a. (image 1–4). (1) The baritone addresses the director after her instruction. (2) The baritone moves toward the soprano to embrace her. (3) The baritone sings and releases the soprano (who is behind the assistant director and baritone, illustrated in red dashed lines). (4) The baritone addresses the director after the depiction.

Figure 2b. (image 1–6). (1) The director readjusts the baritone’s hands. (2) The director starts to move toward the baritone who moves after, while they sing piangi. (3) The director briefly shakes the soprano’s hand and looks at her while singing piangi again. (4) The director strokes the soprano’s arm. (5) The director faces the soprano and grabs her face. (6) The director slowly releases the soprano while singing “ah.”

The baritone starts to sing, fully achieving the depiction of embracing the soprano and singing the last line before piangi (lines 1–2). When he begins to sing piangi, he releases the soprano in the same way as in , not addressing the soprano at alines The director simultaneously starts to move with the baritone, while her right hand remains on his arm, in this way guiding his movements (line 3). She also joins baritone in the singing (line 6), thus achieving a co-depiction (cf., Cantarutti, Citation2021, Citation2022—that is, a simultaneous depiction of the behavior of the baritone’s character at this point.

Whereas the baritone continues to sing what comes after piangi (fanciulla)Footnote10 and moves further away from the soprano, the director halts her movement, self-repairs, and projects a depiction with precis du gör (“exactly, you do,” line 6). Although she indexes that she will now demonstrate what the baritone has just done, her visuospatial behavior makes evident that she is, in fact, not. When repeating the sung phrase piangi fanciulla, she stresses the last syllable of the word piangi, while simultaneously gazing at the soprano and performing a firm shake of her arm (line 8). The prosodic stress on the “gi” highlights a slight modification of the baritone’s idea of not addressing the soprano, to a version in which the soprano is in fact addressed, albeit only briefly. This further becomes evident in the director’s subsequent description that is meshed with depictions indexed by the deictic sån här (“one of these”) and den här “this one,” lines 12–13). These depictions evoke the contrast pair of the behavior the baritone previously did while rehearsing (cf. “activity thing” in ), to the modified version of his idea of not addressing the soprano at all, addressing her slightly. By not explicitly correcting but implicitly modifying the ideas, the director is showing sensitivity to the performers’ rights to propose ideas. By reformulating the idea in a depiction, however, the director indeed transforms the idea, thereby achieving (partial) rejection of it (see also Mondada, Citation2015; Yasui, Citation2013). Interestingly, the micro-history of this scene allows for the director to depict the modification of the idea before it is described.

On lines 14–15, the baritone claims agency for the idea, although the final version of it is in fact a collaborative achievement. The director then initiates simultaneous description and depiction of what they have accomplished: She hugs the soprano while describing what she is doing (lines 17, 20), before starting to depict also with the vocal/aural modality: singing “ah” and then glossing the subtext of the father’s intention with encouraging his daughter to cry (lines 21–23). The baritone displays agreement (line 30), and the director confirms before concluding the sequence with a positive assessment (line 31).

In , we have seen variations from the pattern of how performers move from describing to depicting their own ideas over time as their interlocutors display access to and alignment and agreement with the proposed idea. As the baritone’s idea originated in the director’s instruction just prior, and there thereby was some access to and inferred agreement with the idea, the baritone does not describe his idea to await alignment and preliminary agreement (as in ) before tentatively depicting it. Further, in contrast to , the baritone does not move on to provide a complete version of his depiction without descriptions, as he is interrupted by the director, who modifies his idea with depictions and subsequent summarizing descriptions.

The analysis in this section thus shows how not only decisions but ideas themselves may be joint achievements during the rehearsals. It also demonstrates how depictions serve not only as proposals but also as displays of understanding (cf., Balantani, Citation2022; Sunakawa, Citation2018). When making proposals that align with previous ideas and arrangements, the performers show their current understanding of the developing aesthetics of the production and contribute to that aesthetics themselves. The director, in turn, may choose to (mildly) challenge that understanding, and thereby further develop the production aesthetics.

Discussion

This article has continued to explore the role of depictions in the process of creating and negotiating performance bodies for an opera production. Whereas previous research has shown why depictions are deployed (Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023), and how they are interactionally achieved (Löfgren, Citation2023a), this paper shows when, in a decision-making micro-history, participants deploy depictions of ideas for creating performance bodies. Proposed ideas for performance bodies become increasingly depictive over decision-making micro-histories as the participants transform abstract prototypes of mundane behavior into concrete behavior that is flavored by the aesthetic style of this performance (see also Lefebvre, Citation2018; Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023).

As in previous studies on interactional histories (e.g., Broth et al., Citation2017; Deppermann, Citation2018; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023), turns become less lexicosyntactic (relying on descriptions) over time. However, in contrast to previous accounts on reductions in complexity over time—in terms of both lexicosyntax (Broth et al., Citation2017; Deppermann, Citation2018; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023) and iconicity (Deppermann, Citation2018; Gerwing & Bavelas, Citation2004; Streeck, Citation2021)—during scenic opera rehearsals, depictions become increasingly complex over time. This can be explained by two factors: (1) features of the joint decision-making process and (2) the nature of depictions in scenic opera rehearsals. The discussion expands on these two in sections 5.1 and 5.2 below.

Features of the joint decision-making process

Moving from talking about the production to performing it is reflected in features of joint decision-making processes. Rather than depicting ideas from the beginning, without describing them (as occasionally observed in previous research on theater rehearsals; cf., Norrthon & Schmidt, Citation2023; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2022, Citation2023), performers in the scenic opera rehearsals studied in this article do interactional work to assure (at least preliminary) epistemic access, alignment, and agreement to their ideas before they depict them (cf., Stevanovic, Citation2012; Stivers, Citation2008). When performer ideas originate in or align with previous ideas and arrangements, such as the director’s instructions just prior, however, the performers depict their ideas directly, as there is already access to and inferred likelihood of agreement with the idea.

By resorting to descriptions—that is, language—to assure that the recipients have access to, align with, and agree with ideas in consecutive steps of their developmental trajectories, the recipients of proposals become inherently involved in idea implementation. In fact, the proposals of performance bodies differ in one important aspect from the implementations-as-proposals discussed in previous research on theater rehearsals (Norrthon & Schmidt, Citation2023; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023). Whereas in these studies, the actors often directly depict the director’s ideas as “proposals” without verbalizing what they are doing, the performers in opera rehearsals take up space on the interactional agenda by formulating proposal turns-at-talk that introduce the normative constraint of some kind of interactional treatment (typically rejection/acceptance, see Houtkoop, Citation1987). In other words, they open up the processes of joint decision making described in this and other research (Houtkoop, Citation1987; Lindström, Citation2017; Magnusson, Citation2021; Stevanovic, Citation2012).

Interestingly, descriptions of ideas fulfill that purpose, whereas normative constraints for adjacency type replies in solely visuospatial behavior are disputed (see Deppermann & Streeck, Citation2018). By introducing them on the interactional agenda through language, with its associated sequential organization, the performers make sure that the others have had a chance to veto a possibly unsuitable idea. One one hand, a proposal that is explicitly expressed always succumbs to the risk of receiving a rejection (although explicit rejections are rare during scenic opera rehearsals as the director uses more delicate ways to “improve” (partially) unsuccessful ideas, cf. above). The potential benefit, however, lies in the fact that the agency, and accountability, for ideas in this manner becomes distributed over a collective, even though they are initially, and perhaps paradoxically, formulated by one individual in a way that implies a deontic claim—that is, a claim of individual agency (cf., Löfgren, Citation2023a). In sum, creating this opera production is a dialogical process, where participants assure the jointness, rather than unilaterality, of decisions (cf., Stevanovic, Citation2012), with its associated risks and benefits.

The nature of depictions

Depictions in opera rehearsals increase in size and detail over time in contrast to previous accounts from interactional histories that show a tendency for grammar, turns, and iconic gestures to decrease in complexity over time and with shared accumulated knowledge (see, for instance, Broth et al., Citation2017; Deppermann, Citation2018; Gerwing & Bavelas, Citation2004; Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2023; Streeck, Citation2021). This has to do with the nature of depictions in opera rehearsals as not merely interactional practices but also the outcome of the interaction, the performing arts in creation (cf., Löfgren, Citation2023a; see also Norrthon & Schmidt, Citation2023). In semiotic terms, depictions are signs, in so far as they are practices for the participants to make sense of each other when collaboratively creating art, and in so far as they represent “prototypes of mundane behavior” (Lefebvre, Citation2018; Löfgren, Citation2023b; Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023). According to the pas-une-pipe-principle,Footnote11 a depiction is not what it depicts (Clark, Citation2016), and this holds for depictions in opera rehearsals as well, in that a depiction of a father mourning his dying daughter is not a real father mourning a dying daughter (only a baritone and a soprano “pretending” to do so). However, in so far as they are the art proper in creation, depictions in opera rehearsals partially violate the pas-une-pipe-principle of depictions: they are the very art that they are referencing (cf., Löfgren & Hofstetter, Citation2023, on introversive vs. extroversive semiosis). It is entirely natural, therefore, that they increase in complexity over time, as the artwork materializes. This is in contrast to “mere” communicative signs that reduce in complexity, presumably for efficiency reasons, with time and as their referents become established.

Depictions enhance access to ideas and make them available for joint scrutiny and editing as they are the very “object” that decisions need to be made on—that is, the production as such at its current state. They are thus a necessary feature of the joint decision-making process of creating performance bodies. Importantly, this current state of the performance, or the ideas themselves, do not exist prior to or independently of the depictions. The ideas take form in the dialogical interaction of opera rehearsals. As illustrated in section 4.2, other participants may intervene in ideas so that they become abandoned, or so that their final implementation—the idea in its most depicted state—is dialogically expressed (Linell, Citation2009). As such, depictions and ideas in proposals display understanding of previous turns and the interactional macro- and micro-histories of the aesthetics of this production. Furthermore, they propose new ideas in line with that understanding and thereby transforms the same aesthetics (cf., Balantani, Citation2022; Sunakawa, Citation2018). This is reminiscent of a fundamental feature of social interaction—namely, the double-sided nature of turns-at-talk as both context-sensitive and context-renewing (see Heritage, Citation1984). When depicting ideas during opera rehearsals, participants show understandings of contexts they themselves reinvent.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Leelo Keevallik, Angelika Linke, Emily Hofstetter, Melisa Stevanovic, Oliver Ehmer, and Stefan Norrthon for valuable comments on earlier versions of this article. I am equally grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their improving remarks. Finally, I want to extend my sincerest thanks to the anonymous opera ensemble who generously allowed me to record and analyze them for the purposes of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Due to ethical restrictions, supporting data is not available.

Notes

1 This term is used to disentangle the metaphorical member’s term body from its concrete and mundane understanding. In previous research on interaction in theater rehearsals, similar phenomena have been referred to as “blockings” (Norrthon, Citation2019, Citation2021), “representational choreographic artefact” (Hazel, Citation2018), or “routines” (Schmidt & Deppermann, Citation2018). The term performance bodies is opted for here as it is a (theoretically informed) member’s term that captures the visuospatial nature of what these participants are creating. What the participants will be doing with vocal/aural resources is already predetermined by the musical notation (in contrast to theater rehearsals where vocal/aural resources are frequently modified for artistic purposes).

2 Although H. Clark (Citation1996, Citation2016, Citation2019) speaks of communicative strategies or methods, this article speaks about descriptions and depictions as interactional practices that participants use to bring about social action (cf. Deppermann & Streeck, Citation2018).

3 Although see Szczepek Reed (Citation2021) for a distinction between depiction and demonstration.

4 In this work, the term modality is reserved for overarching categories of interactional resources, based on Enfield’s (Citation2005) distinction between the visuospatial and vocal/aural modalities. The two modalities in turn consists of different resources (i.e., minimal meaning-making units). Lexicosyntax, speech, prosody, and voice quality are conceived of as vocal/aural resources whereas movements, postural changes, gestures, gaze, and facial expressions are conceived of as visuospatial resources.

5 Explicit commitment to future action is not always necessary (cf., Huisman, Citation2001; Magnusson, Citation2021) and is rarely observed in opera rehearsals.

6 The remaining the cases in the collection—namely, performer ideas that are accepted (n = 1/36) or rejected (n = 2/36) right away and thereby do not initiate a decision-making micro-history—are not analyzed in this article.

7 To conceal the identity of the participants, personal names are invented.

8 Although the TCU “if one now should have that” (lines 11–13)—together with the visuospatial behavior of decelerating movement speed and gaze shift toward the director—is ambiguous and indexical, it is treated as a request for confirmation by the director.

9 In imperative form.

10 “Young maiden”

11 The pas-une-pipe principle pertains to Magritte’s famous painting in which a painting of a pipe is accompanied by the text ceci n’est pas une pipe (“this is not a pipe”). This curious statement serves to draw the beholder’s attention to the fact that what is represented on the painting is not a real pipe, but precisely a representation (sign) of it.

References

- Balantani, A. (2022). Non-lexical vocalisations + “so_was” as a multimodal package in establishing joint decisions in music rehearsals. Language & Communication, 87, 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2022.07.007

- Broth, M., Cromdal, J., & Levin, L. (2017). Starting out as a driver: Progression in instructed pedal work. In Å. Mäkitalo, P. Linell, & R. Säljö (Eds.), Memory practices and learning: Interactional, institutional and sociocultural perspectives (pp. 113–143). Information Age Publishing.

- Broth, M., & Keevallik, L. (2020). Multimodal interaktionsanalys. Studentlitteratur.

- Cantarutti, M. N. (2021). Co-animation and the multimodal management of contextualization problems when joint “doing being” others. Social Interaction. Video Studies of Human Sociality, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v4i4.128166

- Cantarutti, M. N. (2022). Co-animation in troubles-talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 55(1), 37–58. https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v4i4.128166

- Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, H. H. (2016). Depiction as a method for communication. Psychological Review, 123(3), 324–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000026

- Clark, H. H. (2019). Depicting in communication. In P. Hagoort (Ed.), Human Language: From Genes and Brains to Behavior (pp. 235–247). MIT Press.

- Deppermann, A. (2018). Changes in turn-design over interactional histories – The case of instructions in driving school lessons. In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 293–324). John Benjamins.

- Deppermann, A., & Pekarek Doehler, S. (2021). Longitudinal conversation analysis: An introduction to the special issue. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2021.1899707

- Deppermann, A., & Schmidt, A. (2021). How shared meanings and uses emerges over an interactional history: Wabi Sabi in a series of theatre rehearsals. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 54(2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2021.1899714

- Deppermann, A., Streeck, J. (2018). The body in interaction: Its multiple modalities and temporalities. In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 1–29). John Benjamins.

- Due, B. L. (2016). Co-constructed imagination space: A multimodal analysis of the interactional accomplishment of imagination during idea-development meetings. CoDesign, 14(202), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2016.1263668

- Ehmer, O., & Mandel, D. (2021). Projecting action spaces: On the interactional relevance of cesural areas in co-enactments. Open Linguistics, 7(1), 638–665. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2020-0172

- Enfield, N. J. (2005). The body as a cognitive artifact in kinship representations. Hand gesture diagrams by speakers of Lao. Current Anthropology, 46(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1086/425661

- Evans, B., & Lindwall, O. (2020). Show them or involve them? Two organizations of embodied instruction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(2), 223–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2020.1741290

- Gerwing, J., & Bavelas, J. (2004). Linguistic influences on gesture’s form. Gesture, 4(2), 157–195.

- Günthner, S. (1999). Polyphony and the ‘layering of voices’ in reported dialogues: An analysis of the use of prosodic devices in everyday reported speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 31(5), 685–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)00093-9

- Hazel, S. (2018). Discovering interactional authenticity: Tracking theatre practitioners across rehearsals. In S. P. Doehler, S. Wagner, & E. González-Martínez (Eds.), Longitudinal Studies on the Organization of Social Interaction (pp. 255–283). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Heath, C. (2002). Demonstrative suffering: The gestural (re)embodiment of symptoms. Journal of Communication, 52(3), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02564.x

- Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Polity Press.

- Holt, E., & Clift, R. (2007). Reporting talk: Reported speech in interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Houtkoop, H. (1987). Establishing agreement: An anlysis of proposal-acceptance sequences [ Doctoral dissertation]. Universiteit van Amsterdam. Foris.

- Huisman, M. (2001). Decision-making in meetings as talk-in-interaction. International Studies of Management & Organization, 31(3), 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2001.11656821

- Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Keevallik, L. (2010). Bodily quoting in dance correction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(4), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2010.518065

- Keevallik, L. (2013a). The interdependence of bodily demonstrations and clausal syntax. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 46(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.753710

- Keevallik, L. (2014b). Turn organization and bodily-vocal demonstrations. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.01.008

- Keevallik, L. (2018). What does embodied interaction tell us about grammar? Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413887

- Keevallik, L. (2013b). Here in time and space: Decomposing movement in dance instruction. In P. Haddington, L. Mondada, & M. Nevile (Eds.), Interaction and mobility: Language and the body in motion (pp. 343–370). Walter de Gruyter.

- Keevallik, L. (2014a). Having a ball: Immaterial objects in dance instruction. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, & M. Rauniomaa (Eds.), Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 245–264). John Benjamins.

- Keevallik, L. (2020). Linguistic structures emerging in the synchronization of a Pilates class. In C. Taleghani-Nikazm, E. Betz, & P. Golato (Eds.), Mobilizing others: Grammar and lexis within larger activities (pp. 147–173). John Benjamins.

- Lefebvre, A. (2018). Reading and embodying the script during the theatrical rehearsal. Language and Dialogue, 8(2), 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1075/ld.00015.lef

- Lefebvre, A., & Mondada, L. (2023). Interactional contingencies in rehearsing a theatre scene: The consequentiality of body arrangements as action unfolds. Human Studies, 46(2), 303–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-023-09669-3

- Lindström, A. (2017). Accepting remote proposals. In G. Raymond, G. H. Lerner, & J. Heritage (Eds.), Enabling human conduct, Studies of talk-in-interaction in honor of Emanuel A. Schegloff (pp. 125–143). John Benjamins.

- Lindström, A. (2009). Projecting nonalignment in conversation. A study of the Swedish curled ja. In J. Sidnell (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Comparative perspectives (pp. 135–158). Cambridge University Press.

- Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind and world dialogically. Information Age Publishing.

- Löfgren, A. (2023a). Relocating to depict: Managing the interactional agenda at opera rehearsals. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 56(3), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2023.2235968

- Löfgren, A. (2023b). Bodies to suit the music: Depictions in opera rehearsals [ PhD Thesis] University of Linköping. https://doi.org/10.3384/9789180754026

- Löfgren, A., & Hofstetter, E. (2023). Introversive semiosis in action: Depictions in opera rehearsals. Social Semiotics, 33(3), 601–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2021.1907180

- Magnusson, S. (2021). Establishing jointness in proximal multiparty decision-making: The case of collaborative writing. Journal of Pragmatics, 181, 32–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2021.05.003

- Mondada, L. (2015). The facilitator’s task of formulating citizens’ proposals in political meetings: Orchestrating multiple embodied orientations to recipients. Gesprächsforschung, 16, 1–62. http://gespraechforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2015/gadeppermann.pdf

- Mondada, L. (2018b). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

- Mondada, L. (2018a). Controversial issues in participatory urban planning: An ethnomethodological and conversation analytic historical study. In S. P. Doehler, S. Wagner, & E. González-Martínez (Eds.), Longitudinal studies on the organization of social interaction (pp. 287–328). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Norrthon, S. (2019). To stage an overlap – The longitudinal, collaborative and embodied process of staging eight lines in a professional theatre rehearsal process. Journal of Pragmatics, 142, 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.01.015

- Norrthon, S. (2021). Framing in theater rehearsals: A longitudinal study following one line from page to stage. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 15(2), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1558/jalpp.20370

- Norrthon, S., & Schmidt, A. (2023). Knowledge accumulation in theatre rehearsals: The emergence of a gesture as a solution for embodying a certain aesthetic concept. Human Studies, 46(2), 337–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-022-09654-2

- Schegloff, E. A. (1984). On some gestures’ relation to talk. In M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social interaction: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 266–295). Cambridge University Press.

- Schmidt, A., & Deppermann, A. (2022). Showing and telling: How directors combine embodied demonstrations and verbal descriptions to instruct in theater rehearsals. Frontiers in Communication, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.955583

- Schmidt, A., & Deppermann, A. (2023). On the emergence of routines: An interactional micro-history of rehearsing a scene. Human Studies, 46(2), 273–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-022-09655-1

- Sidnell, J. (2006). Coordinating Gesture, Talk, and Gaze in Reenactments. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 39(4), 377–409. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi3904_2

- Stevanovic, M. (2012). Establishing joint decisions in a dyad. Discourse Studies, 14(6), 779–803. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445612456654

- Stevanovic, M. (2021). Monitoring and evaluating body knowledge: Metaphors and metonymies of body position in children’s music instrument instruction. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(s4). https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2020-0093

- Stevanovic, M., & Frick, M. (2014). Singing in interaction. Social Semiotics, 24(4), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2014.929394

- Stevanovic, M., & Peräkylä, A. (2014). Three orders in the organization of human action: On the interface between knowledge, power, and emotion in interaction and social relations. Language in Society, 43(2), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404514000037

- Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701691123

- Stivers, T., Mondada, L., & Steensig, J. (2011). Knowledge, morality and affiliation in social interaction. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in interaction (pp. 3–24). Cambridge University Press.

- Streeck, J. (2021). The emancipation of gestures. Interactional Linguistics, 1(1), 90–122. https://doi.org/10.1075/il.20013.str

- Stukenbrock, A. (2021). Multimodal gestalts and their change over time: Is routinization also grammaticalization? Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.662240

- Sunakawa, C. (2018). Bodily shadowing: Learning to be an orchestral conductor. In A. Deppermann & J. Streeck (Eds.), Time in embodied interaction: Synchronicity and sequentiality of multimodal resources (pp. 203–230). John Benjamins.

- Szczepek Reed, B. (2021). Singing and the body: Body-focused and concept-focused vocal instruction. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(4).

- Thompson, S. A., & Suzuki, R. (2014). Reenactments in conversation: Gaze and recipiency. Discourse Studies, 16(6), 816–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445614546259

- Urbanik, P., & Svennevig, J. (2021). Action-depicting gestures and morphosyntax: The function of gesture-speech alignment in the conversational turn. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689292

- Veronesi, D. (2014). Correction sequences and semiotic resources in ensemble music workshops: The case of conduction. Social Semiotics, 24(4), 468–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2014.929393

- Weeks, P. (1996). A rehearsal of a Beethoven passage: An analysis of correction talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 29(3), 247–290. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327973rlsi2903_3

- Yasui, E. (2013). Collaborative idea construction: Repetition of gestures and talk in joint brainstorming. Journal of Pragmatics, 46(1), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.10.002