ABSTRACT

Purpose

Topical prostaglandin analogues are commonly used to treat patients with glaucoma, but may cause periocular and periorbital complications known as prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy syndrome (PAPS).

Methods

A literature review was conducted on PAPS. Given the lack of consensus on grading PAPS, glaucoma specialists from Asia convened to evaluate current PAPS grading systems and propose additional considerations in grading PAPS.

Results

Existing grading systems are limited by the lack of specificity in defining grades and consideration for patients’ subjective perception of symptoms. Patient-reported symptoms (e.g., via a self-assessment tool) and additional clinical assessments (e.g., exophthalmometry, lid laxity, differences between tonometry results, baseline measurements, and external ocular photographs) would be beneficial for grading PAPS systematically.

Conclusions

Effective management of PAPS could be facilitated by a common clinical grading system to consistently and accurately diagnose and characterise symptoms. Further research is required to validate specific recommendations and approaches to stage and monitor PAPS.

INTRODUCTION

Topical prostaglandin analogues (PGAs; also known as prostanoid prostaglandin F receptor [FP] agonists) are popular first-line medical treatments for patients with glaucoma.Citation1 However, their use has been reported to induce progressive periocular changes and the development of periorbital side-effects, collectively described as prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy syndrome (PAPS).Citation1

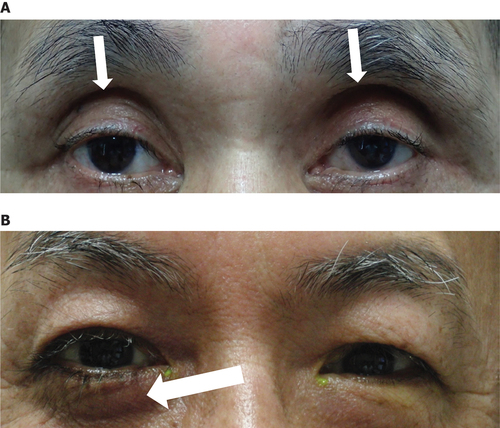

Commonly reported signs and symptoms of PAPS include hyperpigmentation of the periorbital skin, eyelash trichomegaly and hypertrichosis, deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus (DUES), flattening of the lower eyelid bags (FLEB), upper eyelid ptosis, mild enophthalmos, inferior scleral show, and involution of dermatochalasis.Citation1 () However, the list is not exhaustive, and the definitive signs and symptoms of PAPS have yet to be determined. Although the mechanism of PAPS is not fully understood, orbital fat atrophy (the inhibition of adipogenesis through FP receptor stimulation in adipocytes) is believed to be the primary physiopathology.Citation2

Figure 1. Commonly reported PAPS signs and symptoms. Notable signs of PAPS include DUES and FLEB. (A) A patient who had undergone PGA treatment. DUES (arrows) was observed. (B) A patient who underwent PGA treatment in the right eye, and trabeculectomy in the left eye. FLEB (arrow) was observed. Images courtesy of Prof. Makoto Aihara.

The severity of PAPS has been associated with the type of PGA used, with bimatoprost and travoprost having been identified as stronger inducers of PAPS progression than latanoprost and tafluprost.Citation2–8 Other contributing factors to PAPS severity include the duration of PGA use, with some studies reporting signs of PAPS (e.g., DUES) after 3–6 months of PGA use;Citation6,Citation8–11 age (older age, in particular >60 years, is significantly associated with PAPS);Citation6,Citation9,Citation12 and eyedrop instillation technique.Citation13,Citation14 However, more research is required to establish their causal relationships with PAPS.

The presence of PAPS may have a profound and multifaceted impact on patients with glaucoma. For many patients, cosmetic changes associated with PAPS are considered undesirable, especially for patients on unilateral PGA therapy with resulting facial asymmetry.Citation10,Citation15 Furthermore, one study reported a significant decrease in interpupillary distance after topical PGA use of up to 24 months, particularly in patients treated with bimatoprost, which may affect binocular vision.Citation16 PAPS has also been associated with challenges in measuring intraocular pressure (IOP) and performing surgery, which can consequently impact post-surgical outcomes.Citation12,Citation17–20 Globally, it is expected that the prevalence of glaucoma will increase due to aging populations.Citation21 Consequently, cases of PAPS will also increase over time with the growing long-term prescription of PGAs. Specifically, Asian populations may be more susceptible to developing PAPS than patients from other parts of the world. For example, the higher number of melanocytes in the periocular area among South Asians (e.g., Indians) is thought to predispose them to more severe periocular hyperpigmentation from PGA use.Citation10,Citation22 East Asian patients may also be more susceptible to developing DUES due to a lack of superior sulcus depression.Citation9 In addition, ocular adnexa and orbital anatomy are variable within Asia, given the spectrum of Asian ethnicities, and may also differ from Caucasian anatomy.Citation23,Citation24 These anatomical differences may also render Asian populations more susceptible to developing PAPS. Furthermore, myopia, which has a prevalence of approximately 80–90% among young adults in East and Southeast Asia,Citation25 is associated with an increased risk of developing glaucoma.Citation26,Citation27 Consequently, this may further contribute to a higher prevalence of PAPS in Asia. It is therefore important to diagnose and grade PAPS reliably in glaucoma patients treated with PGAs.

Several methods of grading PAPS have been proposed in the literature;Citation12,Citation28 however, no global, or even regional, consensus has been reached regarding a comprehensive and robust PAPS grading system. Consequently, PAPS is currently not well-defined. A common clinical grading system would help maintain consistency in identifying and grading PAPS, thereby enabling clinicians to consider challenges associated with PAPS in their patients’ glaucoma management and adapt their treatment strategy accordingly. Given the lack of consensus on PAPS grading systems, this article seeks to provide an overview of current grading systems as well as to propose additional considerations in grading PAPS, based on the opinions of glaucoma specialists on their relevance and use in clinical practice in Asia.

METHODS

The decision to develop this review article was made by a panel of glaucoma specialists from Asia. A meeting was convened on 23 July 2022 to review and discuss current literature on PAPS, highlight key areas of uncertainty in the field, and delineate potential management strategies for PAPS based on published literature and best practice approaches. A white paper summarising these discussions was subsequently developed in December 2022, highlighting a lack of consensus on clinical staging of PAPS as an unmet need. In response to this unmet need, a second meeting was convened on 9 June 2023 to elicit considerations on the clinical staging of PAPS. This review article summarises the recommendations from the panel, and was reviewed and approved by all authors in November 2023, as a prelude to a formal group consensus approach.

DISCUSSION

Current PAPS Grading Systems

There is currently no consensus guidance on how PAPS should be staged. Difficulties in establishing a reliable, common grading system may be partly due to subjectivity in assessing PAPS and uncertainty around the breadth of relevant signs and symptoms. Several methods of grading PAPS severity have been proposed, notably by Rabinowitz et al. 2015 and Tanito et al. 2021 ().Citation12,Citation28 Rabinowitz et al. 2015 stratified the anatomical features of eyelids and adnexa into three categories.Citation28 Tanito et al. 2021 subsequently proposed the Shimane University PAP (SU-PAP) grading system, classifying PAPS severity into four grades, based on the changes of eyelids and orbits, as well as the reliability of measuring IOP using a Goldmann applanation tonometer (GAT).Citation12

Table 1. Current PAPS grading systems.

Perspectives on Current PAPS Grading Systems

Although the grading system proposed by Rabinowitz et al. 2015 has been useful in clinical trials, its reliability and clinical implications in real-world situations are uncertain.Citation28 Furthermore, this system does not consider the tonometric implications of PAPS (i.e., difficulty in performing IOP measurements).Citation12,Citation28

In contrast, SU-PAP is a simpler grading system which combines cosmetic and tonometric aspects of PAPS, and appears to correlate with the differences observed in the frequency and severity of PAPS associated with different topical PGAs.Citation12 As such, SU-PAP may facilitate clinician grading of PAPS in real-world clinical situations;Citation12 for example, SU-PAP has been used to stratify pre-operative PAPS severity in patients to compare trabeculectomy success rates.Citation29 The grading system developed by Tanito et al. 2021 may also be more relevant to patients in Asia, given its conception and use in Japan.

However, the descriptions of each grade in the SU-PAP system may not be specific enough to provide clear distinction between grades. Furthermore, neither clinical staging method considers patient-reported outcomes on the subjective impact of PAPS. Accounting for the individual patient’s perspective is important in clinical practice, as certain features of PAPS (e.g., eyelash trichomegaly and hypertrichosis) may be perceived as either a positive or negative consequence of PAPS.Citation7,Citation12,Citation28 It may therefore be helpful to consider the patient’s subjective perception of their PAPS symptoms (as either a cosmetic improvement or an adverse event), alongside quantifiable physical measurements in the provision of holistic patient care.

Notably, the effects of PAPS severity on IOP measurements and success rates of filtration surgery require special attention. Certain PAPS signs (e.g., ptosis, DUES, and tight upper eyelid tissue) were noted to have a negative impact on obtaining reliable IOP measurements using GAT.Citation12,Citation17 Similarly, PAPS may lead to tight orbit syndrome, which has been linked to overestimation of IOP.Citation18 Furthermore, difficulties in placement of the eyelid speculum due to enophthalmos and tight eyelids were noted,Citation12 highlighting potential challenges in performing surgery, which could consequently impact surgical outcomes. Hence, grading of PAPS may help clinicians stratify the risks of surgical failure in patients with PAPS who require glaucoma surgery and monitor the progression of PAPS, thereby allowing clinicians to tailor treatment plans.

Given the limitations of current grading systems, there is an unmet need for a reliable and robust grading system for PAPS, which correlates with clinical outcomes, in the management of glaucoma.

Additional Considerations in Grading PAPS

To address the lack of consensus on clinical staging of PAPS and the limitations of current grading systems, the authors explored additional considerations in the systematic and holistic assessment of PAPS. These encompass clinical assessments and patient-reporting tools for PAPS.

Additional Assessments in Grading PAPS

Exophthalmometry to quantify the degree of enophthalmos (retrodisplacement) due to PAPS.

Assessment of horizontal and vertical lid laxity by measuring the lower eyelid position, documenting the prominence of any of the lateral, central, and medial fat compartments, as well as performing objective lid laxity measurements including lid distraction and snapback tests.Citation30–32 However, more research is needed to formulate standardised tests for measuring eyelid tightness and eyelid pressure on the globe specifically observed in PAPS.

The difference in IOP readings between rebound tonometry (which generally does not require eyelid manipulation) and GAT could be used as an indicator of eyelid tightness observed in PAPS patients, but its association with the severity of PAPS requires further investigation. Challenges to this approach would include defining a meaningful numerical difference between the two IOP measurements, and accounting for the influence of corneal thickness on rebound tonometry readings. In addition, although some studies have demonstrated comparable measurements between both methods in the normal population without PAPS, other studies have found an overestimation of IOP readings with rebound tonometry compared with GAT.Citation33–35 To overcome this potential discrepancy in IOP readings, measurements using both rebound tonometry and GAT could be performed at baseline for each patient, and the difference in these IOP values could be used as a reference.

The use of baseline measurements (e.g., exophthalmometry, lid laxity, IOP) could be used as references when monitoring progression of PAPS. Specifically, the number of signs or symptoms observed in the patient and the extent of these changes from baseline could be considered. Considering that orbital evaluations encompass several different components, performing repeat measurements during each follow-up visit could facilitate the accurate monitoring of PAPS and its progression.Citation36 A challenge to this approach would include the feasibility of performing baseline measurements for all treatment-naïve patients, given that these measurements would have to be recorded at each subsequent visit after treatment initiation. Advancements in artificial intelligence could also potentially facilitate automated, accurate measurements of changes in the degree of upper eyelid sulcus or lid distraction in the future.

External photographs to demonstrate and document the progression of PAPS during PGA treatment.

Patient Reporting Tool for PAPS

The development of a PAPS patient reporting tool may facilitate patient self-evaluation of PAPS symptoms. For instance, patients may be asked to compare their symptoms against a list of common signs of PAPS (e.g., hypertrichosis, hyperpigmentation of the periorbital skin, DUES), and indicate the severity of their symptoms (e.g., minimal, visible, or prominent).

Such a tool could encourage patients to express any concerns about treatment, thereby facilitating identification of patient-specific barriers to disease management. A patient reporting tool could also enable healthcare professionals to take a holistic approach to glaucoma management by considering patient-reported outcome measures alongside results from a clinical grading system, therefore allowing them to tailor treatment plans to the individual patient.

Future Suggestions

To strengthen and refine the additional considerations proposed, implementing a modified Delphi panel (i.e., a systematic process of generating consensus from a group of experts on a specific issue) could be helpful for establishing consensus among ophthalmologists on the clinical staging of PAPS.Citation37 Further research is also required to validate specific recommendations, such as establishing the relationship between the risk of surgical failure and PAPS severity, as well as determining a meaningful numerical difference between IOP readings measured via rebound tonometry and GAT. Such research could help promote awareness of PAPS among clinicians and support its clinical management, thereby uplifting standards of care for glaucoma patients by ensuring that the approach to monitoring PAPS remains tailored to each patient’s treatment goals and strategy.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinical staging of PAPS represents a priority area for further research, as the development of a universal grading system could support the early identification and appropriate management of PAPS in patients with glaucoma. Such a grading system would facilitate further research into the severity of PAPS and its progressive nature, thereby raising awareness of PAPS amongst ophthalmologists and patients. Achieving consensus on such a grading system and the subsequent management pathway for PAPS may also contribute towards standardisation of a PAPS-inclusive glaucoma treatment pathway in Asia.

CLi: Honoraria from Allergan (AbbVie), Santen, and Viatris; grant/research support from AbbVie.

TW: Honoraria from Santen.

DL: Consultant/advisor at Allergan (AbbVie), ORBIS International, and Santen; grants from Bayer; honoraria from Santen.

HYLP: Honoraria from Santen.

TA: Grant/research support from Alcon, Allergan (AbbVie), and Santen; honoraria/consultation fees from Alcon, Allergan (AbbVie), Belkin-Vision, and Santen.

MA: Grant/research support from Alcon, Alcon Japan, AMO Japan, CREWT Medical Systems, Glaukos, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Nippon Tenganyaku, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Santen, Sato Pharmaceutical, Senju Pharmaceutical, TOMEY, and Wakamoto Pharmaceutical; honoraria/consultation fees from Alcon, Alcon Japan, Glaukos, HOYA, Iridex, Ono Pharmaceutical, Santen, Senju Pharmaceutical, and Wakamoto Pharmaceutical; speaker’s bureau for Alcon, Alcon Japan, Allergan (AbbVie), AMO Japan, Canon, Carl Zeiss Meditec, CREWT Medical Systems, Glaukos, HOYA, Iridex, Ivantis, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Nippon Tenganyaku, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Santen, Senju Pharmaceutical, TOMEY, and Wakamoto Pharmaceutical.

MM: Grant/research support from AbbVie; advisory board/consultant at AbbVie, Alcon, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Santen, and TRB Chemedica; honoraria from Santen.

SKF: Grants from AbbVie, Johnson & Johnson, and Santen; honoraria from Santen.

KHP: Consultant/advisor at Santen; grant support from Allergan (AbbVie) and Santen; lecture fees from Novartis and Topcon; honoraria from ArcScan and Santen.

CLe: Patents from AIROTA Diagnostics Limited, Carl Zeiss Meditec, and Heidelberg Engineering; grants/research support from Alcon, Arctic Vision, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Heidelberg Engineering, iCare, Implandata, Janssen, Tomey, and Topcon; honoraria from AbbVie, Alcon, Janssen, Santen, Tomey, Topcon, and Zhaoke Ophthalmology; consultant/advisor at AbbVie, Alcon, Arcscan, Janssen, and Santen; owner of ACE VR Limited and AIROTA Diagnostics Limited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Prof. Kelvin Chong (Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Science, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong) for review and input on the manuscript, as well as Olivia Seow and Paige Foo Jia-Qi (Costello Medical, Singapore) for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Sakata R, Chang PY, Sung KR, et al. Prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy syndrome (PAPS): addressing an unmet clinical need. Semin Ophthalmol. 2022;37(4):447–454. doi:10.1080/08820538.2021.2003824.

- Taketani Y, Yamagishi R, Fujishiro T, et al. Activation of the prostanoid FP receptor inhibits adipogenesis leading to deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus in prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(3):1269–1276. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-12589.

- Inoue K, Shiokawa M, Wakakura M, et al. Deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus caused by 5 types of prostaglandin analogs. J Glaucoma. 2013;22(8):626–631. doi:10.1097/IJG.0b013e31824d8d7c.

- Kucukevcilioglu M, Bayer A, Uysal Y, et al. Prostaglandin associated periorbitopathy in patients using bimatoprost, latanoprost and travoprost. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;42(2):126–131. doi:10.1111/ceo.12163.

- Matsuo M, Matsuoka Y, Tanito M. Efficacy and patient tolerability of omidenepag isopropyl in the treatment of glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2022;16:1261–1279. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S340386.

- Patradul C, Tantisevi V, Manassakorn A. Factors related to prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy in glaucoma patients. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2017;6(3):238–242. doi:10.22608/APO.2016108.

- Sarnoff DS, Gotkin RH. Bimatoprost-induced chemical blepharoplasty. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(5):472–477.

- Shah M, Lee G, Lefebvre DR, et al. A cross-sectional survey of the association between bilateral topical prostaglandin analogue use and ocular adnexal features. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(5):e61638. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061638.

- Kim HW, Choi YJ, Lee KW, et al. Periorbital changes associated with prostaglandin analogs in Korean patients. BMC Ophthalmol. 2017;17(1):126. doi:10.1186/s12886-017-0521-4.

- Manju M, Pauly M. Prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy: A prospective study in Indian eyes. Kerala J Oph. 2020;32(1):36–40. doi:10.4103/kjo.kjo_90_19.

- Aihara M, Shirato S, Sakata R. Incidence of deepening of the upper eyelid sulcus after switching from latanoprost to bimatoprost. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55(6):600–604. doi:10.1007/s10384-011-0075-6.

- Tanito M, Ishida A, Ichioka S, et al. Proposal of a simple grading system integrating cosmetic and tonometric aspects of prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy. Medicine. 2021;100(34):e26874. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026874.

- Davis SA, Sleath B, Carpenter DM, et al. Drop instillation and glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29(2):171–177. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000451.

- Inoue K. Managing adverse effects of glaucoma medications. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:903–913. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S44708.

- Tan J, Berke S. Latanoprost-induced prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90(9):e245–e247. doi:10.1097/OPX.0b013e31829d8dd7.

- Sano I, Takahashi H, Inoda S, et al. Shortening of interpupillary distance after instillation of topical prostaglandin analog eye drops. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;206:11–16. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2019.03.013.

- Lee GA, Ritch R, Liang SY, et al. Tight orbit syndrome: a previously unrecognized cause of open-angle glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88(1):120–124. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01755.x.

- Lee YK, Lee JY, Moon JI, et al. Effectiveness of the ICare rebound tonometer in patients with overestimated intraocular pressure due to tight orbit syndrome. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2014;58(6):496–502. doi:10.1007/s10384-014-0343-3.

- Miki T, Naito T, Fujiwara M, et al. Effects of pre-surgical administration of prostaglandin analogs on the outcome of trabeculectomy. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0181550. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181550.

- Pasquale LR. Therapeutics update prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy a postmarketing surveillance observation. Glaucoma Today. 2011;Early Summer 2011:51–58.

- Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081–2090. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013.

- Nouveau S, Agrawal D, Kohli M, et al. Skin hyperpigmentation in Indian population: insights and best practice. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(5):487–495. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5029232/.

- Hickson-Curran S, Brennan NA, Igarashi Y, et al. Comparative evaluation of Asian and White ocular topography. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91(12):1396–1405. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000000413.

- Kiranantawat K, Suhk JH, Nguyen AH. The Asian eyelid: relevant anatomy. Semin Plast Surg. 2015;29(3):158–164. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1556852.

- Morgan IG, French AN, Ashby RS, et al. The epidemics of myopia: aetiology and prevention. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2018;62:134–149. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.09.004.

- Ha A, Kim CY, Shim SR, et al. Degree of myopia and glaucoma risk: a dose-response meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2022;236:107–119. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.10.007.

- Haarman AEG, Enthoven CA, Tideman JWL, et al. The complications of myopia: a review and meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61(4):49. doi:10.1167/iovs.61.4.49.

- Rabinowitz MP, Katz LJ, Moster MR, et al. Unilateral prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy: a syndrome involving upper eyelid retraction distinguishable from the aging sunken eyelid. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(5):373–378. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000000351.

- Ishida A, Miki T, Naito T, et al. Surgical results of trabeculectomy among groups stratified by prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy severity. Ophthalmology. 2023;130(3):297–303. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.10.024.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Lower lid distraction test. American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2024. https://www.aao.org/education/image/lower-lid-distraction-test.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology. Snap back test. American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2024. https://www.aao.org/education/image/snap-back-test.

- Labib A, Patel BC, Milroy C. Lower eyelid laxity examination. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing Copyright 2023, StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2023.

- Esporcatte BL, Lopes FS, Fonseca Netto C, et al. Rebound tonometry versus Goldmann tonometry in school children: feasibility and agreement of intraocular pressure measurements. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2015;78(6):359–362. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20150095.

- Smedowski A, Weglarz B, Tarnawska D, et al. Comparison of three intraocular pressure measurement methods including biomechanical properties of the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(2):666–673. doi:10.1167/iovs.13-13172.

- Termühlen J, Mihailovic N, Alnawaiseh M, et al. Accuracy of measurements with the iCare HOME rebound tonometer. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(6):533–538. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000000390.

- Adewara BA, Singh S. Ocular adnexal changes after antiglaucoma medication use. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2023;63(3):47–58. doi:10.1097/IIO.0000000000000456.

- Nasa P, Jain R, Juneja D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: how to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021;11(4):116–129. doi:10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.116.