Abstract

Gaze direction is a cue that regulates feelings of affiliation in social interactions. Phubbing research suggests that phone-gazing during a copresent interaction hampers the development of affiliation in interactions by signaling that one is not fully attentive. Because the phone represents the “virtual other,” phone-gazing may be more detrimental than gazing at another object. This experimental vignette study explores whether phone-gazing during a conversation harms affiliation more than newspaper-gazing. Additionally, it examines whether the harmful impact of phubbing can be mitigated or aggravated by the phone gazer’s interlocutor role—namely, that of speaker versus listener. The results reveal that phone-gazing during an interaction harms affiliation more than newspaper-gazing. Also, phone-gazing hampers affiliation more while listening than while speaking. These findings suggest that phone-gazing incurs unique judgments of relational devaluation in the interaction partner. The activation of these judgments, however, is contingent upon interlocutor role.

The term phubbing refers to the practice of using one’s phone during face-to-face social interactions (Vanden Abeele, Antheunis, & Schouten, Citation2016). There is growing scientific evidence that phubbing is detrimental to indicators representing conversational and relational quality (e.g., Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, Citation2018; Halpern & Katz, Citation2017; Miller-Ott & Kelly, Citation2017; Misra, Cheng, Genevie, & Yuan, Citation2016; Vanden Abeele et al., Citation2016).

The extant literature identifies a number of related underlying mechanisms that explain why phubbing is harmful: Phubbing behavior is perceived as impolite and face-threatening (Miller-Ott & Kelly, Citation2017; Vanden Abeele et al., Citation2016). It therefore violates conversational expectations (Miller-Ott & Kelly, Citation2015). Phubbing also threatens individuals in their basic needs, leading them to feeling ignored and ostracized (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, Citation2018). In romantic relationships, phubbing predicts lower relationship satisfaction via mechanisms such as jealousy elicitation (Krasnova, Abramova, Notter, & Baumann, Citation2016), conflict over phone use (Halpern & Katz, Citation2017), and lowered intimacy between partners (Halpern & Katz, Citation2017).

Phubbing, Gaze and Mental State Attribution

Several phubbing studies start from the assumption that when phubbers divert their eye gaze to the phone, they signal disinterest in and disengagement from the interaction and interaction partner. For instance, in Karadağ et al.’s (Citation2016) study, lack of eye contact is identified as a prominent reason why phubbing behavior is bothersome. Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas (Citation2018) point toward withdrawal of eye contact as a key feature of phubbing behavior that causes interaction partners to experience social rejection. Halpern and Katz (Citation2017) note that the reduced eye contact that follows from phubbing may be interpreted as a lack of commitment by romantic partners. In short, scholars assume that gaze aversion to the phone plays a key role in explaining why phubbing leads to negative relational outcomes.

This assumption makes sense. Eye gaze is known as an important observable cue that affects the development of affiliation and immediacy in social interactions by regulating visual attention between interaction partners (Burgoon & Hale, Citation1988; Mehrabian, Citation1968). Gaze directed to the conversation partner signals attraction and likeability, whereas gaze aversion signals disengagement and disinterest (see Chartrand & Bargh, Citation1999). This is because the absence of gaze engagement hinders—or at least slows down—highly automatic processes that lead to affiliation (Chartrand & Bargh, Citation1999) and empathy (Marci & Orr, Citation2006), such as nonverbal imitation (Wang, Ramsey, & Hamilton, Citation2011).

People draw on gaze perceptions when forming judgments about the mental state of the person they are interacting with (Shepherd, Citation2010). This process of “mental state attribution” (see theory of mind) is a highly automated cognitive process that explains why averting eye gaze to the phone may lead to perceptions of disinterest and disengagement: When an interaction partner gazes at an object, there is a reflexive shift in the conversation partner’s gaze—an automatic orientation of the gaze to the object (see Posner’s [1980] gaze-cue paradigm). In other words: the conversation partner notices the object that his/her interaction partner is gazing at. The nature of the object to which gaze is diverted may subsequently serve as a piece of information in mental state attribution (Wykowska, Wiese, Prosser, & Müller, Citation2014). In other words, people may use information about an object when incurring judgment about why their interaction partner might visually attend to it (rather than them). When a person averts eye gaze to look at an object that has no immediate relevance to the social interaction, negative judgment from the observing conversation partner may follow as a result of interpreting the lack of eye gaze as a sign of disinterest and disengagement.

The phone is not just any object. Mobile phones render people “permanently online, permanently connected” (see Vorderer, Krömer, & Schneider, Citation2016). They afford a nomadic intimacy (Fortunati, Citation2002) by connecting people to their social networks wherever they are and whenever they want. While mass media channels such as the newspaper or television are also sources of diversion that provide information and stimulation to the user, only the phone is dialogical (Gergen, Citation2002), meaning that—in contrast to the former “monological” media—phones share a unique capacity for interactivity, both with other people and with the device content, that make it harder for them to be ignored or moved to the background. Hence, when users engage with a phone, they enter a flow of virtual interactions that brings them into a state of “absent presence” (p. 227), which is a state of physical presence but mental absence.

Processes of gaze-cue following and mental state attribution explain why averting eye gaze to a nonrelevant object such as a newspaper or phone during a conversation may negatively affect the development of feelings of affiliation in interaction partners. Averting gaze to the phone, however, may be more harmful than averting gaze to a newspaper: When a conversation partner of a phubber notices the phone, this may lead to an automatic activation of implicit associations, most notably of the phubber’s social network outside the immediate spatial context, which may “crowd out” the face-to-face conversation (Przybylski & Weinstein, Citation2013, p. 244). The activation of these implicit representations and associations may lead to a negative perception and evaluation of the social interaction and the relationship with the interaction partner (Misra et al., Citation2016; Przybylski & Weinstein, Citation2013). Hence, because the presence and use of a phone during a conversation may lead to a reflexive activation of representations of and associations with the phone user’s social networks (Fortunati, Citation2002), phone-gazing likely produces an even stronger nonaffiliative response than newspaper-gazing. Hence, we expect that:

H1:

A person who gazes at an object such as a phone (H1a) or a newspaper (H1b) during a conversation will be evaluated as less affiliative than a person who does not avert eye gaze to an object.

H2:

A person who gazes at a phone during a conversation will be evaluated as less affiliative than a person who gazes at a newspaper.

Phubbing-While-Speaking Versus Phubbing-While-Listening

Previous work suggests that the intensity of phubbing behavior, in interplay with the relational and situational context in which it is expressed, matters. Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas (Citation2018), for example, found that more intense phubbing behavior, operationalized as gazing at the phone for a longer period of time, produces stronger effects than less intense phubbing behavior. Miller-Ott and Kelly (Citation2017) found that romantic partners provide disclaimers prior to engaging with their cell phone during interactions as a way to minimize face threats in certain situations. Vanden Abeele et al. (Citation2016) found that self-initiated phubbing behavior was more harmful to impression formation and perceived conversation quality than phubbing behavior initiated in response to a notification. These findings suggest that there may be qualitative differences in the nature and contexts of phubbing behaviors that consequently lead to differences in outcomes.

Interlocutor role might be one aspect that determines the degree of harm of phubbing behavior. Research on gaze direction during conversations shows that it is normal for interlocutors with a speaker role to show less gaze engagement than interlocutors with a listener role (Bavelas, Coates, & Johnson, Citation2012). When speakers avert their gaze, this serves important cognitive functions such as reducing cognitive load and facilitating focus (Freeth, Foulham, & Kingstone, Citation2013). Speakers who occasionally avert eye gaze thus protect the development of affiliation. Listeners, on the other hand, support the speaker most when directing their gaze consistently to the speaker (Bavelas et al., Citation2012). Hence, the more listeners avert eye gaze during a conversation, the more they will activate an automatized mental state attribution process in their interaction partner leading to lower affiliation (Ellsworth & Ross, Citation1975). The latter dynamic may take place when people interact with a phubber: Gazing at the phone while speaking may produce less-negative outcomes than gazing at the phone while listening because the behavior is less likely to be attributed as a signal of disinterest and disengagement. Hence, we expect that:

H3:

A person who phubs-while-listening will be evaluated as less affiliative than a person who phubs-while-speaking.

Method

Research Design and Participants

Similar to Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas (Citation2018), we used a between-subjects experimental video vignette study design to test our hypotheses. Experimental vignettes are advised when experimental studies require both high internal and external validity (Aguinis & Bradley, Citation2014). With respect to internal validity, the hypotheses in our study demand a careful and controlled manipulation of gaze behavior that would be hard—if not impossible—to achieve in an experimental design using a confederate, as it would be extremely difficult for a confederate to consistently “act” gaze behavior in such a way that it is comparable (e.g., in terms of duration and frequency) across conditions. With respect to experimental realism, it is important to apply a study design that enables participants to feel immersed, so that first-person mechanisms can be tested. To that end, we used video vignettes because these are recommended over the use of written vignettes as they heighten realism (Aguinis & Bradley, Citation2014).

The five conditions in our study were: (a) a control condition, in which the video vignette depicted a conversation partner who does not engage in phone-gazing or newspaper-gazing during the interaction; (b) a newspaper condition, in which the conversation partner occasionally gazes at a newspaper; (c) a phubbing condition, in which the conversation partner occasionally gazes at a phone; (d) a phubbing-while-speaking condition, in which the conversation partner gazes at the phone exclusively while she is speaking; and (e) a phubbing-while-listening condition, in which the conversation partner gazes at the phone exclusively while she is listening. In total, 125 participants (64 male; MAge = 24.17, SDAge = 2.46) were evenly distributed across conditions.

Each vignette depicted a 23-second dyadic conversation. Participants were instructed to imagine that they were “the girl in the dark sweater,” who was “in a conversation with the girl wearing a white sweater.” The study was announced as a study on the effect of “elements in the physical environment on conversations.” After viewing the fragment, participants had to evaluate the girl in the white sweater, who was frontally depicted in the video fragment (and who performed the manipulated behaviorFootnote1).

Materials

The vignette videos were shot using two different camera angles. The opening shot, filmed from the front, showed a face-to-face conversation between two young women on a sofa. The remainder of the video was shot over the shoulder of the woman in the black sweater (whom participants were asked to identify with), frontally depicting the woman in the white sweater, whom the participants were asked to evaluate.

The actresses followed a detailed script to ensure that their nonverbal behavior across conditions was highly comparable (e.g., the same amount and duration of shifts in eye gaze). Similar to Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas’s (Citation2018) vignettes, videos were muted so that the first-person perspective was strengthened, and greater comparability across conditions was ensured.

Measures

Participants were asked to indicate their affiliative disposition to the girl in the white sweater. Because two conceptual approaches to affiliation (and therefore also its operationalization) are visible in the literature, we operationalized affiliation using two separate constructs.

Affiliation

Respondents were asked to indicate to what extent 16 trait-descriptive terms from Wiggins’s (Citation1979) IAS-R adjectives scale adequately described the actor in the movie fragment using a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (extremely inaccurate) to 6 (extremely accurate); exemplary items: “gentle,” “unsympathetic” (α = .91).

Affiliation-Extraversion

Affiliation is also oftentimes approached as a subdimension of extraversion (Paunonen & Jackson, Citation1996). Persons with a high score on affiliation typically enjoy being with people, accept people readily, and make efforts to win friendships. We used Paunonen and Jackson’s (Citation1996) five-item scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree) to tap into this conceptualization of affiliation (α = .84). The affiliation and affiliation-extraversion constructs correlated highly (r = .61, Bca 95% CI [.50, .70], p < .001).

Gender and age of the participants were unrelated to the dependent measures and are therefore not included in the main analyses. The assumption of normality was not violated. Because the assumption of homogeneity of variances was violated for the affiliation measure, F(4,120) = 5.82, p < .001, we report results assuming nonequal variances.

Results

Phone-Gazing Versus Newspaper-Gazing

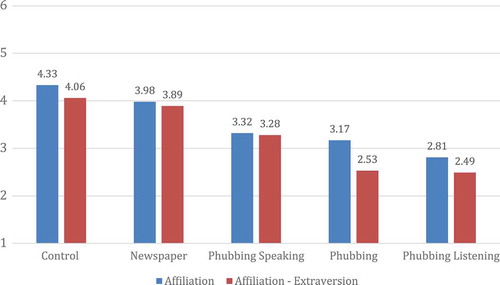

We tested the hypotheses using a bootstrapped one-way ANOVA with four sets of orthogonal contrasts (see for assigned weights). The means per condition can be consulted in . shows the means, the standard deviations and pairwise differences between conditions based on a Bonferroni post hoc test.

Table 1 Assigned Weights in Planned Contrast Tests

Table 2 Means and Standard Deviations per Condition

The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of the conditions on both the affiliation measure, Welch F(4,59.44) = 36.07, p < .001, ŋ 2 = .53, and the affiliation-extraversion measure, F(4,120) = 20.99, p < .001, ŋ 2 = .41. Hypothesis 1 stated that gazing at a phone (1a) and gazing at a newspaper (1b) would produce more negative affiliation evaluations than not gazing at an object during the conversation. Hypothesis 1a was supported: A contrast test comparing the three phubbing conditions to the control condition showed that participants in the control condition gave both higher affiliation, Mdiff = 3.70, SEdiff = 0.36, t(34.28) = 10.33, p < .001, and affiliation-extraversion, Mdiff = 3.87, SEdiff = 0.56, t(120) = 6.97, p < .001, ratings. Compared to the control condition, gazing at a newspaper, however, did not produce lower ratings of affiliation, Mdiff = 0.36, SEdiff = 0.19, t(43.66) = 1.91, p = .063, nor affiliation-extraversion, Mdiff = 0.17, SEdiff = 0.23, t(120) = 0.74, p = .460. Hypothesis 1b was thus not supported.

Hypothesis 2 stated that gazing at a phone would lead to a more negative evaluation than gazing at a newspaper. A contrast test supported this hypothesis: Participants felt more affiliation to the interaction partner in the newspaper condition than in the phubbing conditions, affiliation: Mdiff = 2.64, SEdiff = 0.48, t(29.54) = 5.54, p < .001; affiliation-extraversion: Mdiff = 3.37, SEdiff = 0.56, t(120) = 6.06, p < .001.

Hypothesis 3 stated that phubbing-while-listening would lead to a more negative evaluation than phubbing-while-speaking. Both ratings of affiliation, Mdiff = 0.50, SEdiff = 0.12, t(46.82) = 4.08, p < .001, and affiliation-extraversion, Mdiff = 0.79, SEdiff = 0.23, t(120) = 3.49, p < .001, were lower when participants were exposed to phubbing-while-listening than to phubbing-while-speaking. Hypothesis 3 was thus also supported.

Discussion

This experimental vignette study aimed to compare (a) gaze aversion to a phone, gaze aversion to a newspaper, and no gaze aversion; and (b) phubbing-while-speaking versus phubbing-while-listening in their effect on the development of feelings of affiliation. The findings reveal that occasionally gazing at a phone during an interaction produces lower feelings of affiliation than not gazing at a phone—gazing at a newspaper, however, does not significantly lower affiliation. This finding suggests that the object to which gaze is averted plays a role in activating attributional processes of relational devaluation. Gazing at the phone, in particular, appears to activate cognitive schemata of the phubber’s social network, fueling an attribution process in which the latter schemata serve as the basis for interpreting the phubber’s mental state—namely, a state of being disinterested in the copresent conversation and conversation partner (see also Misra et al., Citation2016, Przybylski & Weinstein, Citation2013).

The finding that directing one’s gaze to the phone is worse during listening than during speaking aligns with the findings of other recent work (Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas, Citation2018), revealing that some displays of phubbing behavior are more harmful than others. Future research needs to further assess what other aspects of phubbing behavior produce negative outcomes. We operationalized phubbing as occasionally gazing at the phone during an interaction. Phubbing may affect other aspects of the interaction than visual attention, however. It may, for example, affect posture or cause response-lags turn-taking processes. We advise an ecological analysis of phubbing behavior that systematically examines which verbal and nonverbal behaviors characterize phubbing as a social practice. Such an analysis could also focus on the difference between being engaged in passive versus active social media use (e.g., scrolling versus messaging). Given that a conversation is a collaborative process (Bavelas et al., Citation2012), a thorough analysis of the precise conditions under which phubbing harms the conversational process could lead to valuable insights that theoretically further our understanding of phubbing and the conditions under which it is most or least harmful.

It is important to also investigate whether and how phubbers may adjust their phubbing behavior in real-life situations to mitigate harm. The interviewees in Miller-Ott and Kelly’s (Citation2017) study, for example, reported providing disclaimers. In addition, aspects of the situation or context likely moderate how harmful phubbing is to relational outcomes. For instance, in contexts that come with expectations of full attention (e.g., dinner in a restaurant), phubbing behavior is likely evaluated more negatively than in contexts where less attentive behavior is tolerated (e.g., at home watching television).

We used video vignettes for the experimental manipulation. Participants did not experience the phubbing behavior firsthand but were asked to “imagine” it. This lowers the study’s ecological validity. Moreover, there is a risk that responses were colored by normative judgments of phubbing behavior being depicted. However, most participants failed to guess the true purpose of the study, which suggests that the vignettes did not elicit a deliberate reflection on phubbing norms; excluding the participants who guessed the true purpose of the study from the analysis also did not influence the findings (see the appendix). Moreover, we found a marked difference between being exposed to phubbing-while-speaking and phubbing-while-listening, a difference that we consider unlikely to result from a deliberate reflection on phubbing norms. Nonetheless, we advise future researchers to include a manipulation or induction check, as well as measures that tap into participants’ engagement level with the vignette and the vignette conversation partner—for example, a perceived psychological realism or social presence measure. Researchers are also advised to pretest materials to examine how perceived realism may be increased (e.g., by not muting the vignette).

In conclusion, this study is the first to directly compare phone-gazing to newspaper-gazing and the interplay between phubbing and interlocutor role in the effect on affiliation. The results indicate that the effect of phubbing on relational outcomes is a matter of more than just gaze. Phubbing incurs unique judgments of relational devaluation in the interaction partner. The activation of these judgments, however, is contingent upon the phubber’s interlocutor role.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

[1] Still images from our videos, as well as the videos themselves, were not included with this manuscript so as to protect the identity of the confederates who were used in this study. However, all study videos are available on request from the primary author of this work.

References

- Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371. doi:10.1177/1094428114547952

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2012). Listener responses as a collaborative process: The role of gaze. Journal of Communication, 52, 566–580. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2002.tb02562.x

- Burgoon, J. K., & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Communication Monographs, 55, 58–79. doi:10.1080/03637758809376158

- Chartrand, T., & Bargh, J. (1999). The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 893–910.

- Chotpitayasunondh, V., & Douglas, K. M. (2018). The effects of “phubbing” on social interaction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48, 304–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12506

- Ellsworth, P., & Ross, L. (1975). Intimacy in response to direct gaze. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11, 592–613. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(75)90010-4

- Fortunati, L. (2002). The mobile phone: Towards new categories and social relations. Information, communication & society, 5(4), 513–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180208538803

- Freeth, M., Foulham, T., & Kingstone, A. (2013). What affects social attention? Social presence, eye contact and autistic traits. PloS One, 8(1), e53286. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053286

- Gergen, K. J. (2002). The challenge of absent presence. In J. E. Katz & M. Aakhus (Eds.), Perpetual contact: Mobile communication, private talk, public performance (pp. 227–241). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Halpern, D., & Katz, J. E. (2017). Texting’s consequences for romantic relationships: A cross-lagged analysis highlights its risks. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 386–394. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.051

- Karadağ, E., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., Erzen, E., Duru, P., Bostan, N., Şahin, B. M., … Babadağ, B. (2016). The virtual world’s current addiction: Phubbing. Addicta: Turkish Journal on Addictions, 3(2), 252–269. doi:10.15805/addicta.2016.3.0013

- Krasnova, H., Abramova, O., Notter, I., & Baumann, A. (2016, June). Why phubbing is toxic for your relationship: Understanding the role of Smartphone Jealousy among “Generation y” users. Paper presented at the European Conference on Information Systems, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Marci, C. D., & Orr, S. P. (2006). The effect of emotional distance on psychological concordance and perceived empathy between patient and interviewer. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31, 115–128. doi:10.1007/s10484-006-9008-4

- Mehrabian, A. (1968). Inference of attitudes from the posture, orientation, and distance of a communicator. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 32(3), 296. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0025906

- Miller-Ott, A. E., & Kelly, L. (2015). The presence of cell phones in romantic partner face-to-face interactions: An expectancy violation theory approach. Southern Communication Journal, 80, 253–270. doi:10.1080/1041794X.2015.1055371

- Miller-Ott, A. E., & Kelly, L. (2017). A Politeness theory analysis of cell-phone usage in the presence of friends. Communication Studies, 68, 190–207. doi:10.1080/10510974.2017.1299024

- Misra, S., Cheng, L., Genevie, J., & Yuan, M. (2016). The iPhone effect: the quality of in-person social interactions in the presence of mobile devices. Environment and Behavior, 48(2), 275–298.

- Paunonen, S. V., & Jackson, D. N. (1996). The Jackson Personality Inventory and the Five Factor model of personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(1), 42–59. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1996.0003

- Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2013). Can you connect with me now? How the presence of mobile communication technology influences face-to-face conversation quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 30(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407512453827

- Shepherd, S. V. (2010). Following gaze: Gaze-following behavior as a window into social cognition. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 4, 5.

- Vanden Abeele, M. M., Antheunis, M. L., & Schouten, A. P. (2016). The effect of mobile messaging during a conversation on impression formation and interaction quality. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 562–569. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.005

- Vorderer, P., Krömer, N., & Schneider, F. M. (2016). Permanently online–Permanently connected: Explorations into university students’ use of social media and mobile smart devices. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.085

- Wang, Y., Ramsey, R., & Hamilton, A. (2011). The control of mimicry by eye contact is mediated by medial prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 12001–12010. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0845-11.2011

- Wiggins, J. S. (1979). A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(3), 395. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.3.395

- Wykowska, A., Wiese, E., Prosser, A., & Müller, H. J. (2014). Beliefs about the minds of others influence how we process sensory information. PLoS One, 9(4), e94339. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094339

Appendix

Descriptives and ANOVA Test Results for the Subsample of Participants Who Did Not Correctly Assess the True Nature of the Study