Abstract

This study elucidates the process of Maria Casarès’ identity construction in her correspondence with Albert Camus. I focus on how space and identity are entangled in their letters by zooming in on the correspondents’ construction of a spatial identity through their epistolary dialogue. In their epistolary relationship, Casarès and Camus exchange depictions, feelings, drawings, and postcards of the places in their host country France—such as Paris, Ermenonville in Oise, Camaret-sur-Mer in Bretagne, Cabris in the Provence—, that define them not so much individually but mostly together, as a couple. The correspondents create in their letters places and metaphors that have significance for both of them and that they can share—through memory of the past, imagination at present, or plans for the future—. The analysis gives insight in how Casarès renegotiated her identity via the epistolary dialogue with Camus on the basis of the characteristics of exile and the search for silence, creativity and truth that they shared. The study illustrates the autobiographical character of the correspondence in its dialogical context: the strong bond between the sender and recipient of the letters plays a fundamental role in stimulating and facilitating possibilities for synergetic identity renegotiations.

Two Exiles in Paris: The Story of an Alliance in Letters

In 2017, Francine Camus, daughter of Nobel prize winner Albert Camus (1913–1960),Footnote1 edited the letters written by her father and his lover, the actress Maria Casarès (1922–1996).Footnote2 Casarès is a mythic actress of the Spanish exile (Aznar Soler “Materiales,” “María Casares,” “El compromiso”), muse of French existentialism and one of the national glories of theater and cinema in postwar France. Camus’ daughter gathered the correspondence and Gallimard publishing house, which played a key role in Camus’s life and tragic early death, published this extraordinary and intense epistolary ().

The volume recounts in nearly nine hundred exchanges and nearly 1300 pages the illicit love story of Albert Camus and María Casarès, stretching from the summer of 1944 to the winter of 1959. It is a collection of primary source material transcribed from original letters, postcards, and telegrams that reads like a powerful work of epistolary fiction. It is less a correspondence than a story, one co-written in the form of an intense dialogue by two artists.

Their love affair started in Paris, on the sixth of June 1944, the day the Allied forces landed in Normandy. Casarès had fled her native Spain in 1936 as a young girl and was sent to France by her father, who was prime minister when Francisco Franco began his military revolt against the elected republican government. Camus had gone into exile from Algeria to France in 1940, arriving on the eve of the Nazi invasion. When she arrived in Paris, Casarès studied theater and philosophy, the same subjects Camus had pursued a decade earlier, as a student in Algiers, the capital of French Algeria. Camus published his novel L’Etranger in 1942. In Paris, in Spring 1944, both exiles were involved in the production of Camus’ play Le Malentendu which was being staged in Paris at the Théâtre des Mathurins and in which Casarès played one of the leading roles. That evening of the sixth of June, the two began their love affair, Casarès twenty-one, Camus nine years her senior. Due to the occupation of France, Camus lived since 1942 separated from his wife Francine Faure, pianist and mathematician, who stayed back in Algeria. The lovers’ affair did not last long and ended abruptly when Camus’s wife returned from Algeria to Paris after the liberation.

After this rupture, Camus and Casarès each went their own ways for a couple of years. Camus had been active in the French Resistance and worked as editor in chief of Combat, the underground newspaper. In 1945, Camus’ wife gave birth to twins, Catherine and Jean. Camus earned great success with his second novel, La peste, published in 1947. Meanwhile, Casarès was conquering the Paris’ audience as the leading actress of the city’s renowned Théâtre des Mathurins. She was then cast in three of her most memorable film roles, and impressed the audience as the incarnation of a young and pure girl in Les enfants du paradis, as a strong woman who exacts a cruel revenge on her former lover in Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, and as the duchess who tries to save the man she loves from execution in La Chartreuse de Parme. Four years to the day after their first meeting, on June 6, 1948, Casarès ran into Camus by chance on Boulevard Saint-Germain and their passion took flight again. It would continue uninterrupted for the next twelve years until Camus’s sudden death in 1960. During their twelve years together, Casarès and Camus were often separated due to health issues, professional duties, and family matters, which explains the frequency of their correspondence.

After Camus’ death, his friend René Char found Casarès’s letters to her lover and handed them back to the actress. Casarès kept these letters all her life until, a few years before her death, she accepted to sell them to Catherine Camus. Their intense correspondence includes many stories and is the lyrical co-written account of their passionate love. Furthermore, it is also an autobiographical document that casts light on their daily professional activities, an intimate testimonial of the beliefs, ethical values, and emotions of two fellow-exiles. The book, on one of the great love affairs in French literary history, attracted the attention of the audience and the international press, and became a best-seller in France. The first edition of the epistolary generated a large number of reviews, both in France and abroad (Borel, Cariguel, Fletcher, Libiot, among many others), that have in common a focus on the dramatic circumstances of this love affair and on the life and work of Camus.

At an academic level, the correspondence has been analyzed mostly from the viewpoint of Albert Camus’ oeuvre and thoughts. The letters have been considered style exercises for Camus. They also have been read in the context of Camus’ literary development throughout the three great cycles of his work, connected, respectively, with the mythical figures of Sisyphus, Prometheus and Nemesis (Kletz-Dreapeau). Especially the conception and development of the last cycle, “L’amour de Némésis” has been connected with Camus’ love for Casarès. In this same context of Camus’ work, Lopo argues that the letters also give information on aspects previously unknown of Casarès’s active contribution to Camus’s dramatic work as a reader, translator, and advisor, going beyond her (known) role as a source of inspiration (Lopo “A Galicia de Camus”). The critics have also shown an interest in the relationship between the concepts and expression of time, love, and authenticity in Camus’ work, on the one hand, and in his letters, on the other (Neiman, Hylari, Fessaget).

From the perspective of Maria Casarès, the epistolary has been analyzed in its professional and performative dimension (Houvenaghel “Entre tú, yo y la carrera”). Houvenaghel shows how the epistolary dialogue reveals the career struggles and victories of the correspondents and emphasizes how Casarès and Camus resort to each other’s letters to cope, through dialogue, with pressure, fatigue, a high work rhythm, and difficulties to focus and concentrate. Still, most of the richness of this correspondence, particularly from Casarès’ viewpoint or in a more balanced dialogical approach, remains unexplored. In this article, I focus on how space and identity entangle in the letters by zooming in on the correspondents’ construction of a spatial identity through their epistolary dialogue.

Spatial Identity through Dialogue

Maria Casarès’ Self-Writings: From Monologue to Dialogue

The letters written to her lover, Albert Camus, are not Maria Casarès’s only autobiographical texts. Her self-writings also include Résidente privilégiée, a profound autobiographical essay of well over 400 pages in which autobiographical testimony and essayistic reflection are combined. In this text, Casarès recalls how exile took her, as a teenager, from Spain to France and how she developed as a person in French exile.Footnote3 Résidente privilégiée received attention from the critics (Aznar Soler “Materiales,” Grillo, Coca Méndez, Mourier Martínez, and Ezama Gil), but the reaction of the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier stands out. He emphasizes the volume’s literary value and expresses his admiration for Casarès’ writing style ():

Ya no pensamos que es una actriz quien nos habla, sino una extraordinaria escritora, en una prosa de una riqueza, de un vigor, de una garra, absolutamente excepcionales. ¡Muy pocas novelistas de hoy podrían jactarse de poseer un señorío del vocablo, un dominio de la frase, un poder de expresión, semejante a los que aquí se imponen a nuestra atención! Por primera vez en mucho tiempo nos hallamos ante “Memorias” –llamémoslas así–que son, para empezar y ante todo, una magnífica obra literaria.Footnote4 (Carpentier)

C’est aussi pourquoi malgré une latente envie d’écrire qui est venue toujours tracasser mes rares moments de loisir, écartelée comme je le suis entre deux langues qui me narguent en se camouflant l’une l’autre, […] j’ai préféré me rendre à l’authenticité–par l’interprétation–ou l’interpénétration–des trouvailles parfois divines créées par d’autres.Footnote7

The dialogical character is a fundamental feature of the letter as an autobiographical genre: “First, letters are dialogical. They are not one person writing or speaking about their life, but a communication or exchange between one person and another or others” (Stanley 202). The letter, contrary to the intimate diary or autobiography, represents a dialogue, a (written) conversation (Violi “Letters,” “Intimacy”), an interaction between two persons. The self-portrait included in the letter is created for a specific person, the recipient of the letter. The dialogical situation in which it is conceived adds a dimension to the letter’s potential for self-discovery and brings the letter closer to the confession. The confessional genre, according to María Zambrano (29), has a close relationship with the foundation of the subject, because the individual, when confessing, constructs the self while revealing it to the other. The letter is written, thus, as a manifestation of the individual subject addressing a specific receiver and is a “revelation of himself under the gaze of an addressee” (Bouvet 70).

Maria Casarès’ “Autocartography”: From Individual to Shared Places

In Résidente privilégiée, Casarès conceives the process of her own identity construction in spatial terms, as a journey of self-discovery. Casarès writes her book as a “search for her own centre” (Houvenaghel, “Hacia el centro”) and reaches this center through a journey along the important places of her life. In her memoirs, space dominates time, “the structuring of the volume is not done based on a temporal logic but rather obeys a spatial structure and aesthetics” (Houvenaghel, “Hacia el centro”). In this sense, and given the works’ emphasis on spatial poetics, I propose that the term “autocartography” is better suited than “autobiography” or “memoirs” to describe how Casarès’ “maps” herself in Résident privilégiée.

In this sense, Casarès’ appoach to her own identity fits with the “cartographies” or “mapping projects” that are practical elaborations of Bachelard’sFootnote9 theoretical proposals concerning the understanding of space. Under Bachelard’s influence, the idea of space has changed from an empty, fixed, passive concept into a relational, changing, and performative concept. As a consequence of this “spatial turn,” space has become the object of theoretical disquisitions from various disciplinary fields such as literature, anthropology, and sociology. These elaborations in the form of “cartographies” or “mapping projects” make it possible to “resignify” spaces by approaching them from the angle of their historical, cultural, political, social, emotional, and symbolic dimensions.

Within this framework, Fernando Aínsa’s geopoetics focus on the transformation and function of space in literature how places are artistically transformed and resignified in texts. Aínsa explains how the appropriation and representation of places (topos), is performed through poetic expression (logos), that is, through the artistic verbalization of the author’s perception of place. Aínsa’s geopoetics study the spatial symbols and images in texts that resignify places by making them personal and linking them to the author’s identity: “El lugar es el elemento fundamental de toda identidad, en tanto que autopercepción de la territorialidad y del espacio personal” (22–23).Footnote10

When we connect these insights with Casarès’ Résidente privilégiée, we observe how the actress describes the process of writing her memoirs in terms of space and identity:

En janvier 1979 […] j’ai entrepris le long voyage […]. Familière d’espaces ouverts, j’ai dû m’enfoncer sous la terre. […] je cherchais dans l’ordonnance des mots […] les signes qui me révéleraient enfin une identité. Coupée de tout, sourde et aveugle à tout ce qui m’entourait, je poursuivais mon exploration souterraine. […] (Casarès, Résidente 419–420).Footnote11

Shared Spaces

Demonizing Paris; Mythicizing Ermenonville

The most important places on the correspondents’ map are Paris, the city where their paths initially crossed and where they were professionnally based, and Ermenonville, in the Oise region where Camus and Casarès stayed together on several occasions. Other places in France where they stayed together are also included in Camus and Casarès’ “cartography” of love: the high Cordes-sur-Ciel, in the Tarn region, Cannes in the Alpes-Maritimes on the Côte d’Azur, and the mountains of Les Vosges in the Alsace region. Still, Paris and Ermenonville are the places they most reconstruct and appropriate as their own in their letters.

Their relationship with Paris is ambivalent. On the positive side, Paris is the city of their love, and the correspondents picture themselves walking together by night in its streets and on its quays, particularly in the initial letters. On the negative side, Paris is portrayed as a demanding, exhausting and even hostile city, full of rush, pressure, obligations, intruding media, quarrels, problems, and fatigue. Camus and Casarès give testimony of their struggle with these challenges. As their relationship develops, the negative image of Parisian life gradually takes over and the correspondents become accomplices in their shared aversion toward the city.

Either way, for the correspondents, the only way to live in the city or to imagine it is together. When looking at Paris from the positive side, Casarès expresses this need to be united in Paris as followsFootnote12: “Paris est superbe en ce moment. Chaque coin que je regarde t’appelle. Viens, mon bel amour, viens vite. Je t’attends à chaque minute, à chaque coin de rue […] (Casarès to Camus [07 March 1950] 491).”Footnote13 Camus, for his part, when thinking of Paris, writes: “je pense à Paris. Nous le détestons bien parfois, mais c’est la ville de notre amour. Quand je marcherai à nouveau dans ses rues et sur ses quais, avec toi près de moi, ce sera la guérison d’une longue maladie – cruelle comme l’absence” (Camus to Casarès [14 July 1949] 145).Footnote14 This Paris, the city of their love, is associated with emptiness, loneliness, coldness, or strangeness, when they are in Paris without the other. When regarding Paris from the negative side, the correspondents emphasize how they need to address the challenges of the city together: “tu dois redouter ce retour à la cage aux fauves qu’est Paris; mais je voudrais que, comme moi, l’idée d’y revenir ensemble, pour y lutter ensemble, te redonne le courage necessaire” (Casares to Camus [25 August 1952] 992).Footnote15 The city becomes only bearable when it is faced together: “Si tu n’étais pas à Paris je supporterais mal le retour dans cette ville,”Footnote16 writes Casarès to Camus ([11 December 1954] 1137). Camus agrees: “Je serai content de te retrouver, toi, et toi seule qui me fais tout supporter à Paris” (Camus to Casarès [05 May 1955] 1146).Footnote17 This Paris, this demanding city, is associated with hell, mist, anguish, and sterility.

The juxtaposition of the couple’s self-portrayals in Paris in their subsequent letters illustrates the development of their relationship with the city. Their first letters of the late 1940s and early 1950s show how the lovers adopt a bird perspective on the city, looking at Paris’ rooftops from Casarès’ balcony, where they become the secret kings of the city who continue to “régner sur Paris” (Camus to Casarès [14 August 1948] 61). “Nous sommes les rois de cette ville,” writes Camus, “les rois secrets et heureux, transportés” (Camus to Casarès [12 August 1948] 59).Footnote18 In later years, this feeling develops and they consider themselves as condemned to the city: “tu seras là, mon amour, condamné comme moi, à vivre dans ce repaire” (Casarès to Camus [27 August 1952] 996).Footnote19 Finally, in the last phase of their epistolary exchange, they express their dreams and visions of leaving Paris together, of buying a property in a different place, of being together somewhere else: “Une fois de plus je ne comprends pas ce que l’on fait à Paris,” writes Casarès, “et une fois de plus je songe à faire des économies” (Casarès to Camus [21 November 1954] 1130).Footnote20 Camus wishes to live with Casarès far away from Paris: “Vivre avec toi loin de Paris, dans un pays qu’on puisse aimer matin et soir, voilà ce que je désire plus que tout” (Camus to Casarès [3 November 1953] 1085).Footnote21

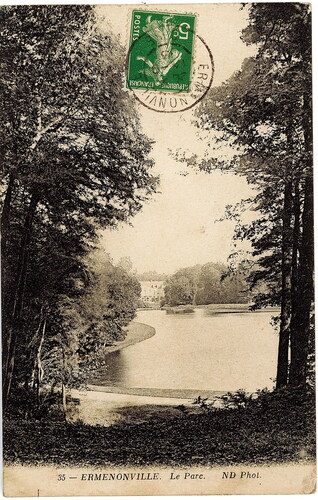

In 1949, after Camus’ journey in Latin America, he and Casarès realize their first stay together in Ermenonville ( and ). They will return several times to its beautiful park and lake. Unlike Paris, Ermenonville is constructed in the letters as a place of rest, peace, calm, silence, and profound happiness. It is a place that gives them strength, whereas Paris has the opposite effect on them by taking their energy away. By means of hyperbolic descriptions, the correspondents mythicize Ermenonville as their own personal space of perfect union and eternity.

For Casarès, the stays are a reason to live: “C’est pour cela qu’il faut vivre, […] pour les heures de paix d’Ermenonville et de son parc […]” (Casarès to Camus [28 February 1950] 456).Footnote22 The moments lived together in Ermenonville are unforgettable: “Nous oublierons peut-être bien des choses, des larmes et certaines joies,” writes Casarès, “mais les heures d’Ermenonville […] nous les porterons jusqu’à la fin” (Casarès to Camus [28 May1950] 456).Footnote23 These periods in Ermenonville are so exceptional that they justify, for Casarès, a whole existence (Casarès to Camus [03 August 1953] 1038).

Camus associates Ermenonville with “l’heure parfaite près du lac, dans le ciel d’Ermenonville” (Camus to Casarès [16 january 1950] 258), with “l’éternel été” and with intense feelings of happiness “jusqu’au cœur” (Camus to Casarès [13 September 1949] 193).Footnote24 Their stays in Ermenonville are, for Camus, Casarès’ most beautiful gifts: “Je te dois les plus grands jours, et les plus silencieux, qu’on puisse trouver sur cette terre impitoyable” (Camus à Casarès [13 September 1949] 193).Footnote25 Ermenonville is also associated by Camus with the powerful sun and full light, as opposed to the misty and pale Paris (e.g. Camus to Casarès [14 February 1950] 409, Camus to Casarès [05 June 1950] 680). The sun is a significant metaphor in Camus’ construction of places on which I will elaborate later.

The questions they ask each other on Ermenonville emphasize the correspondents’ need to reinvigorate the memory of these stays. Camus repeatedly asks if Casarès remembers the parc of Ermenonville and if she wishes to return to its peaceful environment to regain strength. Casarès reacts with vigor: “Ah ! mon ensoleillé, oui, je veux aller à Ermenonville, oui, je veillerai sur moi, oui, je revivrai, oui, oui, oui!” (Casarès to Camus [06 march1950] 484).Footnote26 Also, in times of difficulties, Casarès invites Camus to think of their days in Ermenonville. Camus agrees that these moments by the lake have given him a great “provision de force” (Camus to Casarès [04 August 1953] 1041).Footnote27 “Oui, tu as raison,” he writes, “c’est aux soirs d’Ermenonville qu’il faut penser. Et j’y pense, j’y pense toujours pour trouver le courage qu’il faut […]” (Camus to Casarès [02 march1950] 468).Footnote28

Back to the Roots while Staying in France: Camaret-sur-Mer and Cabris

Camus and Casarès were both exiles and they expressed this condition in their work: the sense of foreignness is present in several theatrical roles interpreted by Casarès and is the underlying theme of various writings by Camus. Both correspondents construct in their letters a special place in France, away from Paris, with which they feel a connection and that reminds them of their roots, in Algeria or Spain, respectively. They create, by means of their descriptions, a place that enables them to identify with a part of their host country without losing their unique identity as exiles ().

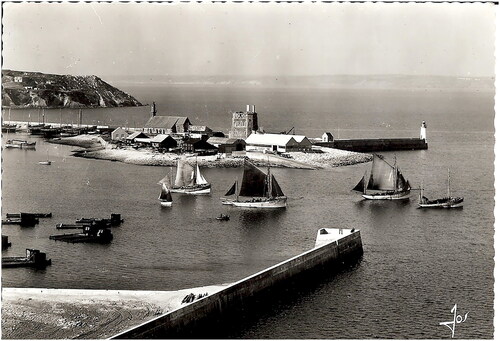

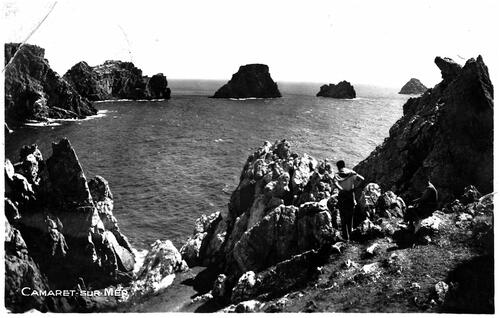

Casarès depicts Camaret-sur-Mer, a port in the Finistère department in Bretagne, which has a privileged location surrounded by the Ocean at the entrance of the Brest Channel. She went there as a young girl in 1937 with her mother, only 7 months after her arrival in Paris (Casarès Résidente privilégiée 153–155) and would later return several times. In her memoirs Résidente privilégiée, Casarès describes in detail her first stay in Camaret-sur-Mer. Casarès remembers how the French port brought back the Galicia of her childhood ().

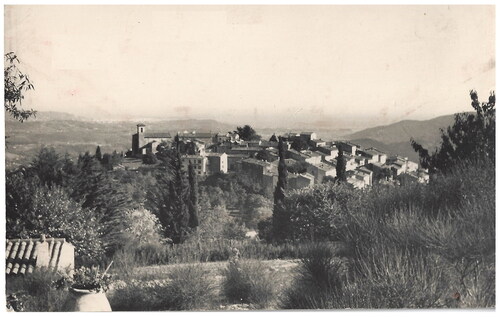

Camus, on his part, describes his temporal residence in Cabris, near Grasse, in the hot and dry climate of the Côte d‘Azur in the Provence-Alpes-Maritimes region. Due to tuberculosis from which he suffered, the doctors prescribed longer stays in agreeable Cabris’ climate in 1950 and 1951. The house in Cabris, high on the dry hills and with its marvelous light, transports Camus back to his country of origin. He considers the Provence, in which he recognizes the same atmosphere of serenity and silence that characterizes his home land (Vircondelet), as a land of his own. Subsequent to his stays in Cabris, Camus makes plans to relocate, away from Paris, to the Provence. Eventually, in 1958, his dream became true: with the money of the Nobel Prize, Camus bought a property in Lourmarin, south of Luberon in the Vaucluse, in the Provence region.

It is Camus who first mentions Camaret-sur-Mer in the correspondence. When traveling to his home country Algeria to spend time with his mother, Camus connects this stay at his roots with Casarès’ Bretagne. He starts making plans for the day when she will take him to her “Bretagne prénatale” (Camus to Casarès [20 December 1948] 102). A few years later, Casarès will spend the summer of 1952 in Camaret and Camus, who is traveling toward his wife and children, “accompanies” her, in spite of his physical absence, by sending a telegram to her hotel to welcome her in Camaret-sur-Mer at the beginning of her stay (Casarès to Camus [31 July 1952] 958). Casarès answers that she hugged the telegram as it arrived in the hotel, practically at the same time as she did (Casarès to Camus [02 August 1952] 958).

Their correspondence during Casarès’ stay in Camaret develops from the memories of her previous stays as a young girl with her mother, in the first letters, into dreams and plans of staying at the seaport with Camus. In the first stage of the correspondence, Casarès tells how little the French port has changed since her previous stays: “Camaret, immuable au point de douter si je l’ai jamais quitté” (Camus to Casarès [02 August 1952] 954).Footnote29 Camaret reminds her of the days spent there with her mother: “j’appellerais maman à tous les coins de rue et je serais bien étonnée qu’elle ne réponde point” (Camus to Casarès [02 August 1952] 954)Footnote30 (, and ).

Casarès sends him a series of six postcards of Camaret (fishing boats, quays, view of Sillon with the St. Mary of Rocamadour Chapel and the Fortress, Pointe de Pen Hir, old fishermen’s houses) and adds her personal descriptions of a landscape that she finds is “digne de tendresse” (Casarès to Camus [05 August 1952] 960),Footnote31 which is confirmed by Camus in his answer. Casarès adds how Camaret reminds her of her childhood back in Galicia and hereby uses the Galician word morriña, which captures nostalgy, sadness, and homesickness. She emphasizes how intense her relationship with Camaret is: “[Ce pays] me bouleverse toujours et à chaque minute.” (Casarès to Camus [08 August 1952] 972).Footnote32

In his letters, Camus is in his thoughts already with her in the seaport, longing for “ce que pourraient être nos journées de Camaret” (Camus to Casarès [05 August 1952] 963), or dreaming “puérilement” of Camaret (Camus to Casarès [09 August 1952] 972).Footnote33 He exclaims: “Comme je serais heureux, avec toi, près de la mer!” (Camus to Camarès [06 August 1952] 963) ().

Casarès urges him to discover Camaret one day with her and sends a postcard of the chapel, chosen especially for him, as it would, in her view, please him very much (Casarès to Camus [10 August 1952, 969]. She confesses that in front of the chapel, she made a secret wish for the two of them together. She exclaims: “comme nous serions heureux ici!” (Casarès to Camus [10 August 1952] 969).Footnote34 The following postcard she sends him represents the old mill of Quermeor that Casarès wishes to purchase, and in which she imagines staying together with Camus ():

Voilà un petit moulin que je rêve d’acquérir chaque fois qu’en allant au bain je passe devant lui. Il appartient, pour le moment, au propriétaires d’une maison de pêcheurs exquise, mais je suis habituée aux révolutions et rien ne peut m’empêcher de croire qu’un jour il sera mien. Tant que j’y pense, j’ai du plaisir à t’imaginer en meunier. (Casarès à Camus [10 August 1952] 970).Footnote35

Cette lumière m’allait jusqu’au cœur et en même temps j’étais triste. Je pensais à toi. Nous vivons seulement les villes, la fièvre, le travail – et toi et moi pourtant sommes faits pour cette terre, pour la lumière, la joie tranquille des corps, la paix du cœur. Il faudra changer tout cela, n’est-ce pas? […] nous pouvons […] fuir toute cette hideuse vanité qui nous entoure, et vivre un peu dans la vérité. (Casarès to Camus [21 January 1950] 288)Footnote38

At the beginning of his stay in Cabris, and in the same way as Casarès did in Camaret-sur-Mer, Camus shares the place in which he resides with Casarès by depicting his room, and by describing his view of a landscape filled with olive trees and cypresses, and, further away, of the valley that leads to the sea. He sends her a drawing of the ground plan of the house in which he resides and a postcard to show her the view from his room. (Camus to Casarès [7 January 1950] 218) Casarès, in her answer, feels joy and thanks the nature for surrounding Camus so well: “Je suis heureuse du temps qu’il fait dans tes montagnes, des promenades en plein ciel, du ruissellement de mimosas, et je remercie l’amandier que tu vois à travers la fenêtre pour avoir été bon avec toi.” (Casarès to Camus [26 February 1951] 847).Footnote40 All the joy that the Provence gives Camus is shared happiness: “Regarde et vois le soleil, pour toi et pour moi et le beau ciel bleu. […] Goûte à tout pour moi. Jouis de tout pour nous deux.” (Casarès to Camus [9 January 1950] 218).Footnote41

During his first phase in Cabris, Camus imagines that Casarès becomes a secret companion on his walks through the mountains: “[…] je me suis promené seul. Le soleil me chauffait doucement, je te tenais par la main et nous marchions ensemble dans la montagne” (Casarès to Camus [07 February1950] 377).Footnote42 After several months, Camus longs for this imagined presence to become reality. He even wishes that her theater work in Paris would stop for a while, because this interruption would enable Casarès to make the journey to the Provence: “J’imagine parfois que la pièce s’arrête et que tu t’installes, à Cannes ou ailleurs, que tu y es heureuse et que je viens mordre à ce bonheur, tous les jours. Est-ce vraiment impossible?” (Camus to Casarès [22 April 1950] 580).Footnote43 A few days later, Casarès travels to the Provence to be with Camus for a couple of days.

In this same period, Camus writes to Casarès how he starts his search in the Provence for a quiet house to live and work. He intends to find “un refuge,” “un balcon sur la mer” in the environment of Cabris (Camus to Casarès [22 April 1950] 579).Footnote44 He pictures her at his side in the future when arriving in the Provence: “Je suis ici à Saint-Rémy de Provence […] J’aime ces vielles villes de Provence […] Un jour, nous arriverons dans une ville pareille et nous arriverons dans la beauté” (Camus to Casarès [28 May 1950] 656).Footnote45 Casarès would travel later, in the early 1950s, several times to stay in Avignon, where she worked intensely with Jean Vilar at the Festival d’Avignon. By the end of the 1950s, Camus found his house in the Provence, where he established with his family. The house is described in his letters to Casarès in terms that correspond to his very first description of the region, by emphasizing its silence and simplicity: “Je te parlerai de cette maison. Elle serait favorable à la meditation silencieuse, au travail, et aussi à la vie toute simple.” (Camus to Casarès [17 December 1958] 1334).Footnote46

Self Development in Metaphors: Sea and Sunlight

To bridge the distances between them, Casarès and Camus both use metaphors. They identify with these images as their ideals into which they wish to develop in dialogue with the other. Casarès connects with the sea, Camus with the sunlight: these symbols correspond to the places in France they feel connected with, Camaret-sur-Mer and the Provence, respectively.

In Résidente privilégiée, Casarès elaborates on the similarities between her relationship with the sea and her theater work: both the sea and her role as performer at the theater oblige her to give herself completely, to abandon herself and to reach a different state of consciousness (Houvenaghel “Hacia el centro”). She gives testimony of her experience of becoming one with the sea, abandoning herself to the waves, “dans une divine volupté, ne faisant plus qu’ une avec la mer” (Casarès Résidente privilégiée 199).Footnote47 In the same way, she gives herself completely to her theater work and loses herself to achieve a greater and more creative union with her play. The interpretation of a theater role requires “renoncer à toute volonté d’affirmation ou de conquête, et s’abandonner à la marée montante qui sait célébrer les noces de la création, divine ou humaine” (Casarès Résidente privilégiée 199).Footnote48 The intensity of the abandonment and the union that Casarès describes is comparable to the experiences lived by the Spanish mystics (Houvenaghel “Hacia el centro”). This spiritual trance is related to Grotowski’s conception of theater work as a trance, as a way to loose the self via the play and to discover new, different states of conscience.

In her correspondence with Camus, Casarès presents herself as the personification of the sea, and refers abundantly to this metaphor during longer periods of separation from her lover. Her letters persistently argue that this identification with the sea enables Camus to feel her presence, especially when he is traveling by sea or staying in places where he can see the coastline. In his answers, Camus confirms how Casarès’ identification with the sea makes it possible for him to feel close to her and how strong an impact these imagined meetings have on his mind and heart:

Depuis deux jours, nous sommes sur ton océan […]. Je vais voir la mer le matin […] je regarde la mer du midi […] je finis la journée devant la mer. […] Je suis là, devant cette mer qui m’aide, et elle seule, à tout supporter. Quand le jour sur cette immensité point […] j’ai mes rendez-vous avec toi. Et chaque jour mon coeur se gonfle comme l’océan lui-même, plein de cet amour tourmenté et heureux […] Tu es présente […]. (Camus to Casarès [5 July 1949] 132)Footnote49

Mais écoute donc. Ecoute bien. Ne bouge plus, et là, au milieu de cette mer immense qui t’entoure – ma mer – entend. J’aime trop cet océan pour qu’il puisse me trahir, […] si enfin, nu, tu te tournes vers cette eau où je me suis faite, tu m’entendras crier mon amour comme jamais je ne l’ai crié devant toi, près de toi. (Casarès to Camus [30 juin 1949] 126)Footnote51

For his part, Camus connects in the letters with the sun, which is an important metaphor in his literary works and thought. The writer links sunlight and brightness with the idea of the divine and with the revelation of truth.Footnote53 In his letters, Camus often pictures himself in the sun: in his room while reading, at his desk while writing words “au beau milieu d’une flaque d’or” (Camus to Casarès [27 December 1948] 100),Footnote54 or outside in the mountains while walking or resting. Casarès points out that feeling the sun is Camus’ most vital need: “J’ai rarement rencontré quelqu’un qui ait un besoin vital de soleil comme toi.” (Casarès to Camus [31 January 1950] 332).Footnote55

Camus wishes that Casarès gets acquainted with the man he becomes when he resides in sunnier regions. He explains that the sunlight is an essential element that enables his self development and makes him reach his full identity: “Il faudra que tu me connaisses dans le soleil. Ce que je suis à Paris, n’est pas moi, c’est un délégué que mon vrai moi envoie dans les pays de brume” (Camus to Casarès [25 February 1950] 447).Footnote56 He writes from Algeria how he would like to take her to sunnier lands with the objective of showing her his full identity: “Il fait beau. Les matins sont ensoleillés et tendres. Je suis réveillé par le soleil sur mon lit et je passe alors une petite demi-heure, nu, dans le doux soleil naissant. Toute ma journée s’en ressent ensuite. Je mesure mieux alors l’ombre que je suis à Paris et je voudrais que tu vives un peu ici avec moi pour que tu me voies l’air d’un homme, enfin” (Camus to Casarès [February 23 1955] 1152).Footnote57

This rapprochement of Casarès toward the sun occupies a special place in the correspondence. Camus refers at numerous occasions to the sun on Casarès’ body. His wish to create a fuller existence in a brighter and sunnier environment is a dream that includes Casarès’ participation: “Mais nous descendrons ensemble vers le soleil. Un temps viendra où malgré toutes les douleurs nous serons légers, joyeux et véridiques. N’est-ce pas, mon amour chéri, nous fuirons ces pays d’ombres, […] et nous serons de beaux et bruns enfants de Midi” (Camus to Casarès [26 février 1950] 450).Footnote58

Camus also reflects and elaborates on the significance of the sun and sea together, as a combined metaphor: “Hier, j’ai trouvé dans un livre cette définition du soleil: le feroce oeil d’or de l’éternité. Mais c’est Rimbaud qui a raison, l’éternité, c’est la mer mêlée au soleil.” (Camus to Casarès [27 December 1948] 100).Footnote59 The verses by Rimbaud, quoted by Camus, refer to the bond of silence and eternity that was forged between Casarès and Camus in Ermenonville. Casarès expresses the joy she finds in their alliance by means of the same combined image, and hereby takes the changing sea as a starting point: “Quant à moi, je suis les rires, les sourires, les colères, les plaintes et les orages de la mer près de laquelle je suis née, mais aujourd’hui le soleil brille partout dans l’océan et j’ai envie de crier d’amour, d’enthousiasme” (Casarès to Camus [06 February1950] 367).Footnote60

A Place for Us

The spatial identity that Camus and Casarès co-write and develop in their epistolary dialogue is entangled in several ways. Their selfhood has a marked spatial dimension that is constructed on the basis of their feelings of comfort or unease in response to the places that they consecutively inhabited. First, the places that identify Camus and Casarès are built on their roots in their respective home lands. This is how they stay true to their authenticity, without turning their back on their host country. Secondly, the places that identify the actress and writer are based on their artistic experience in Paris. In their professional trajectories of acting and writing, certain values of harmony, peace, and truth, have acquired an important place because they create the possibility to achieve a communion with nature and to connect with eternity. Their spatial identity constructed in this period has in common that it enables Camus and Casarès to move away from rush, futility, and pressure with the objective to live closer to intense silence and simplicity. These values are for them essential to achieve a different level in life and in their creations. The cartography of love they co-trace via their correspondence is, thus, most of all, a pathway to the development of a true and full identity.

Still, their spatial identities are constructed, expressed, experienced, polished, and improved together. The dialogical character of the correspondence, which is one of the starting points of this study, is instrumental in forging their selves. The correspondents need each other in the process of discovering the spatiality of the self. Without the presence of the other, and without the strong bond with the other, these identity projects could never have been initiated nor pursued. It is through the alliance with the other that Camus and Casarès get gradually stronger and closer to their full selves.

Casarès, with her characteristical humor, synthesizes the multiplicity of their joint cartography of love, toward the end of their correspondence, when she is coming back from one of her international theater tours. Multiple spaces are, indeed, an integral constituent of this couple’s identity. The actress states that she plans to procure a nice caravan, purchase that would enable her to connect smoothly the important dots on their shared map: “M’en rentrant de tournée j’achète une belle roulotte. Et voilà! Plus d’ennuis. Tu es à Lourmarin? J’y viens m’installer. Avons-nous envie de la Bretagne? Qu’à cela ne tienne! Du Midi? Partons dans le Midi” (Casarès to Camus [30 juin 1959] 1380).Footnote61

The analysis of the correspondence in combination with Casarès’ autobiography Résidente privilégiée gives an insight in how Casarès renegotiated her identity via her epistolary dialogue with Camus on the basis of the characteristics of exile and search for unity, pureness, and truth that they shared. This study thus illustrates the autobiographical character of these letters in their dialogical context: the strong bond between the sender and recipient of the letters plays a fundamental role in stimulating and facilitating possibilities for synergetic identity renegotiations.

Figure 4. Post card of park and lake at Ermenonville. from the site Geneanet: https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/5911317#0.

Figure 5. Department of Oise, France by TUBS, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:D%C3%A9partement_60_in_France_2016.svg.

Figure 6. Department of Finistère sur. Original map: Sting, modifications by Wikialine, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Finist%C3%A8re_departement_locator_map.svg.

Figure 7. Department of Alpes-Maritimes, France by TUBS, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:D%C3%A9partement_06_in_France.svg.

Figure 8. Postcard with fishing boats, Camaret-sur-Mer, from the site Geneanet https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/6102329#0.

Figure 9. Postcard with Le Sillon, the Chapel of St. Mary of Rocamadour, and the Fortress, Camaret-sur-Mer, from the site Geneanet. https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/36110#0.

Figure 10. Postcard with Pointe de Pen Hir, Camaret-sur-Mer, from the site Geneanet. https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/124561#0.

Figure 11. Postcard with the mill of Quermeor, Camaret-sur-Mer, from the site Geneanet. https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/1355031#0.

Figure 12. Postcard with view of Cabris, from the site Geneanet. https://www.geneanet.org/cartes-postales/view/7812422#0.

Notes

1 Albert Camus (1913–1960) was a French novelist, essayist, and playwright who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. His most important novels are L’Etranger (1942), La Peste (1947) and La Chute (1956), his essays Le Mythe de Sisyphe (1942), L'Homme révolté (1951), and his plays Caligula (1944), Les Justes (1949), and Les Possédés (1959). For more information about his life see Looking for the stranger: Albert Camus and the life of a literary classic (2016) by Alice Yaeger Kaplan, and Albert Camus (2015) by Edward J. Hughes. For critical essays about Camus, see Albert Camus: From the Absurd to Revolt (2014) by John Foley, and Albert Camus in the 21st Century: A Reassessment of his thinking at the Dawn of the New Millennium (2008), edited by Christine Margerison et al.

2 For more information on her life and career, see Casarès (Citation1980 Résidente, 1981 and 2022 Residente), Figuero and Plantagenet, Lopo (O tempo), Plantagenet and Estévez. Maria Casarès was born in Spain, but lived in exile in France since 1936, when the Spanish War broke out and her father, Santiago Casares Quiroga, minister and head of the government of the Second Spanish Republic, had to resign and go into exile. She studied acting at the Paris Conservatory and became one of the great actresses of twentieth century French theatre. She was recognized by French critics and public as one of the greatest interpreters of the postwar period. She worked with the most important theatre directors in France and toured all over the world. At the same time, Casarès showed throughout her life an ethical, political, and social commitment to her Spanish origin, to the ideals of the Republic, and to refugees. At the beginning of her career, in the forties and early fifties, she undertook an intense and successful journey in the world of cinema. Some of her most prestigious film projects include her role in the classic Les enfants du paradis, her leading role in Les dames du Bois de Boulogne, or her role as princess-death in Orphée. From the fifties onwards, her career focused on theatre. The actress decided not to continue her film career because of how shootings were organized, with long pauses and interruptions. The fragmentary method of filming each sequence did not coincide with Casarès' conception of the work of acting. The actress performed numerous theater roles created by French writers linked to existentialism, such as Camus, Sartre, Anouilh, Cocteau, Genet, and Claudel, among others. Casarès thus became the muse of French existentialism. Casarès worked in the Comédie Française and the Théâtre National Populaire, a company with strong social objectives that conceived theatre as public service. She interpreted female figures such as Medea, Fedra, Lady Macbetch, Maria Tudor or Anna Petrova, strong women and reincarnations of classical or historical myths. She also played roles in the great works of the late 19th and early 20th centuries famous playwrights, such as Brecht, Pirandello, Valle Inclán and García Lorca. She participated in the creation of the Avignon Festival, was a great promoter of its development and collaborated in memorable works with Jean Vilar. Casarès wrote, in French, an autobiographical text entitled Résidente privilégiée. After her death, the actress left her country house in La Vergne to the local community, which transformed it into the Maison Maria Casarès, today a dynamic centre of study and training for young actors.

3 The book was translated into Spanish a year after its first publication in French (1980). Later it was translated into Galician (2009) and in 2022, on the occasion of the centenary of the actress's birth, the 1981 Spanish translation was reissued with an introduction by María Lopo.

4 “We no longer think that it is an actress who speaks to us, but an extraordinary writer, in prose of absolutely exceptional richness, vigor, and strength. Very few novelists today could boast of possessing a mastery of the word, a mastery of the phrase, a power of expression, similar to those that attract our attention here! For the first time since we stad before Memoirs – let's call them that – which are, to begin with and above all, a magnificent literary work.” (Carpentier, my translation)

5 “It’s true,” explains Casarès, “a word that is used exactly in the right way – invented, rediscovered, or restored – can move me to tears or make me laugh with joy.” (Casarès Résidente 144) All translations of the Casarès autobiography (or “autocartography”) are mine. The original text to which I refer is the 1980 Fayard French edition.

6 “This is why I have always liked to perform the language of poets in the theatre” (Casarès Résidente 144).

7 “This is also why, despite a latent desire to write which has always come to bother my rare moments of leisure, torn as I am between two languages which taunt me by obfuscating each other, […] I preferred to embrace authenticity—by means of the interpretation—or the interpenetration—of sometimes divine finds created by others” (Casarès Résidente 144–145).

8 The correspondence between Casarès and her father was edited by María Lopo in 2008 (Cartas no exilio). In addition, Manuel Aznar Soler (“Doce cartas”) compiled and published in 2017 twelve letters sent by Rafael Alberti, José Bergamín, Alejandro Casona, Jean Cassou, Jacinto Grau, and Margarita Xirgu to Maria Casarès.

9 After Bachelard’s poetics of space, other proposals related to the conception of space followed—by Fernando Aínsa, Henri Lefebvre, Doreen Massey, Kenneth White, Bernard Westphal, among others—.

10 “Place is the fundamental element of all identity, as self-perception of territoriality and of personal space” (Aínsa Del topos: 22–23).

11 “In January 1979 […] I started the long journey […]. Used to open spaces, I had to go underground. […] In the act to setting the words in order, […] I was looking for signs that would finally reveal an identity to me. Cut off from everything, deaf and blind to everything around me, I continued my underground exploration” (Casarès Résidente 419–420).

12 All translations of the correspondence between Camus and Casarès are mine. The original text to which I refer is the 2017 Folio French digital edition.

13 “Paris is beautiful right now. Every corner I look at calls you. Come, my beautiful love, come quickly. I'm waiting for you every minute, at every corner” (Casarès to Camus [07 March 1950] 491).

14 “I think of Paris. We hate it sometimes, but it is the city of our love. When I will be walking again through its streets and along its quays, with you beside me, it will be like the healing of a long illness—as cruel as absence can be” (Camus to Casarès [14 July 1949] 145).

15 “You must fear this return to the cage of wild beasts that is Paris; but I would like that the idea of returning there together, to fight there together, would give you the necessary courage in the same way as this thought gives me strength” (Casares to Camus [August 25 1952] 992).

16 “If you weren't in Paris, I wouldn't be able to stand my return to this city” (Casarès to Camus [11 December 1954] 1137).

17 “I will be happy to meet you again, you, and you alone, makes me endure everything in Paris” (Camus to Casarès [05 May 1955] 1164).

18 “We are the kings of this city,” writes Camus, “the secret and happy kings, elated” (Camus to Casarès [12 August 1948] 59).

19 “you will be there, my love, condemned like me, to live in this den” (Casarès to Camus [August 27 1952] 996).

20 “Once again I don't understand what we are doing in Paris, […] and once again I am thinking of saving money” (Casarès to Camus [21 November 1954] 1130).

21 “To live with you far away from Paris, in a land that I can love morning and evening, that is what I desire more than anything else” (Camus to Casarès [3 November 1953] 1085).

22 "That is why you have to live, […] for the peaceful hours of Ermenonville and its park […]” (Casarès to Camus [28 february 1950] 456).

23 “We may well forget many things, tears and certain joys,” writes Casarès, “but we will carry the hours of Ermenonville […] with us to the end” (Casarès to Camus [28 May 1950] 456).

24 Camus associates Ermenonville with “the perfect hour near the lake, in the sky of Ermenonville” (Camus to Casarès [16 January 1950] 258), with “the eternal summer” and with intense feelings of happiness “to the heart” (Camus to Casarès [13 September 1949] 193).

25 “I owe you the greatest days, and the most silent, that one can find on this merciless earth” (Camus to Casarès [13 September 1949] 193).

26 “Ah ! my sunny, yes, I want to go to Ermenonville, yes, I will take care of myself, yes, I will live again, yes, yes!” (Casarès to Camus [06 march1950] 484).

27 “provision of strength” (Camus to Casarès [04 August 1953] 1041).

28 “Yes, you are right” […] “it is about the evenings of Ermenonville that we must think. And I think about them, I always think about them to find the courage that it is necessary […]” (Camus to Casarès [02 March 1950] 468).

29 “immutable to the point of doubting whether I ever left the place” (Camus to Casarès [02 August 1952] 954).

30 “I would call mum on every street corner and I would be very surprised if she did not answer” (Casarès to Camus [02 August 1952] 954).

31 “worthy of tenderness” (Casarès to Camus [05 August 1952] 960)

32 “This land always sets me upside down at every minute” (Casarès to Camus [08 August 1952] 972).

33 “what our days in Camaret could be” (Camus to Casarès [05 August 1952] 963), or dreaming “childishly” of Camaret (Camus to Casarès [09 August 1952] 972).

34 “How happy we would be here!” (Casares to Camus [10 August 1952] 969)

35 “Here is a small mill that I dream of acquiring. Every time I go to the sea, I pass in front of it. It belongs, for the moment, to the owners of an exquisite fisherman's house, but I am used to revolutions and nothing can prevent me from believing that one day it will be mine. When I think about it, I enjoy imagining you as a miller” (Casares to Camus [10 August 1952] 970).

36 “It is to the Provence that we should go together, while waiting for the opportunity to travel to other countries that are close to our hearts” (Camus to Casarès, [6 July 1944] 23).

37 “Finally, Cabris. There is true silence. Vast landscape in front of the village on a peak, the air is pungent and light. Something woke up inside me. A smell of grass and I saw Ermenonville again […]” (Camus to Casarès [10 August 1952] 218).

38 “This light went to my heart and at the same time I was sad. I was thinking of you. We only live in cities, fever, work – and yet you and I are made for this land, for light, the quiet joy of our bodies, peace of heart. All of that will have to change, won't it? […] we can […] run away from all this hideous vanity that surrounds us, and live a little in the truth” (Casares to Camus [21 January 1950] 288).

39 “Ah! How happy we would be here, even in winter” (Casarès Résidente 419–420, 446).

40 “I am happy with the weather in your mountains, the walks in the sky, the trickling of mimosas, and I thank the almond tree you see through the window for being good to you” (Casares to Camus [26 February 1951] 847).

41 “Look and watch the sun and the beautiful sky, for you and for me. […] Taste everything for me. Enjoy everything for both of us” (Casarès to Camus, [09 January 1950] 218).

42 “[…] I walked alone. The sun warmed me gently, I held your hand and we walked together in the mountains” (Casarès to Camus [07 February 1950] 377).

43 “I sometimes imagine that the theatre play stops and that you establish yourself, in Cannes or elsewhere, that you are happy there and that I come to bite into this happiness, every day. Is it really impossible?” (Casarès to Camus [22 April 1950] 580).

44 “a refuge,” “a balcony on the sea” (Camus to Casarès [22 April 1950] 579).

45 “I am here in Saint-Rémy de Provence. […] I love these old towns of the Provence […]. One day, we will arrive in such a city and we will arrive in beauty” (Camus to Casarès [28 May 1950] 656).

46 “I will tell you about this house. It is favourable to silent meditation, to work, and also to the simple things of life” (Camus to Casarès [17 December 1958] 13).

47 “a divine voluptuousness, becoming one with the sea” (Casarès Résidente privilégiée 199)

48 “to renounce any desire for affirmation or conquest, and to abandon oneself to the rising tide that knows how to celebrate the nuptials of creation, divine or human” (Casarès Résidente privilégiée 199)

49 “For two days we have been on your ocean […]. I go and watch the sea in the morning […] I look at the sea at noon […] I am there, in front of this sea who helps me, she alone, to bear everything. When the day breaks to this immensity, I have my meetings with you. And every day my heart swells like the ocean itself, full of his tormented and happy love […] You are present […] (Camus to Casarès [05 July 1949] 132).

50 “But even so I loved this sea and I spent long hours in her company. […] I spent most of my time with her. It was spending it with you” (Camus to Casarès [14 July 1949] 144).

51 “But listen to me. Listen carefully. Do not move, and there, in the middle of this immense sea that surrounds you – my sea – listen. I love this ocean too much for her to betray me […] look at the sea at noon […] If finally, naked, you turn towards this water where I was made myself, you will hear me cry out my love as I have never cried it out before you, near you” (Casarès to Camus [30 June 1949] 126).

52 “The sea is in front of you. Look how heavy, dense, rich, strong she is: look how she lives, frightening with power and energy, and think that, through you, I have become a little like her. Know that when I feel sure of your love, I do not envy the sea for being so beautiful; I love her as a sister” (Casarès to Camus [30 June 1949] 126).

53 This symbol is elaborated, for example, in the collection of essays Noces (1938), in the novel L’Etranger (1942), in the essay L’Eté (1954) and in the short stories included in L’Exil et le Royaume (1957). For more information on Camus’ relationship with the sun, see Roblès and Chabot.

54 “In the beautiful centre of a puddle of gold” (Camus to Casarès [27 December 1948] 100).

55 “I have rarely met someone who has such as vital need for sun as you” (Casarès to Camus [31 January 1950] 332).

56 “It is necessary that you know me in the sun. What I am in Paris is not me, it is but a decoction that my real self sends to the land of the mist” (Casarès to Camus [31 January 1950] 332).

57 “The weather is beautiful. The mornings are full of sunshine and tender. The sun shines on my bed and wakes me up. I spend then almost half an hour, naked, in the soft rising sun. This changes my whole day. The shadow I am in Paris does not measure up to the man I become here. I would love you to live here a little with me so that you would see me finally as a real man” (Camus to Casarès [February 23 1955] 1152).

58 “But we will descend together towards the sun. A time will come when despite all the pain, we will be light, joyful, and truthful. Is it not true, my cherished love, that we will flee the land of the shadows, […] and we will become the beautiful and tanned children of the South” (Camus to Casarès [26 février 1950] 450).

59 “Yesterday, I found in a book this definition of the sun: the fierce golden eye of eternity. But it is Rimbaud who is right, eternity is the sea mixed with the sun” (Camus to Casarès [27 December 1948] 100).

60 “As for me, I am the laughter, the smile, the anger, the complaint, and the storm of the sea close to which I was born, but today the sun shines everywhere in the ocean and I would like to cry out from love, from enthusiasm” (Casarès to Camus 06 February 1950] 367).

61 “When returning from the tour, I will buy a nice caravan. And that is that ! No further difficulties. You are in Lourmarin ? I will come there to settle for a while. Do we like to go to Bretagne ? Never Mind ! To the South ? Let us leave for the South” (Casarès to Camus, [30 juin 1959] 1380).

Works Cited

- Aínsa, F. Del topos al logos. Propuestas de geopoética. Iberoamericana, 2006.

- Aznar Soler, Manuel. “El compromiso republicano de María Casares, comendadora de la Orden de la Liberación de España en 1952.” Des espaces de l’Histoire aux espaces de la création, editado por Lina Iglesias y Béatrice Ménard, PU de Paris Nanterre, 2020, s.p.

- Aznar Soler, Manuel. “Doce cartas inéditas de Rafael Alberti, José Bergamín, Alejandro Casona, Jean Cassou, Jacinto Grau y Margarita Xirgu a María Casares.” Anales de la literatura española contemporánea, vol. 40, no. 2, 2015, pp. 503–31.

- ———. “María Casares, Margarita Xirgu y el estreno de Yerma, de Federico García Lorca, en el Teatro Municipal General San Martín de Buenos Aires, 1963.” Género y exilio teatral republicano: entre la tradición y la vanguardia, editado por Francisca Vilches de Frutos, Pilar Nieva de la Paz, José Ramón López García y Manuel Aznar Soler, Rodopi, 2014, pp. 165–179.

- ———. “Materiales para la memoria de un mito: María Casares y el exilio republicano español de 1939.” Congreso Internacional do Exilio Galego. Consellería de Cultura, Comunicación Social e Turismo, 2001.

- ———. “Materiales para la memoria de un mito: María Casarès y el exilio republicano español de 1939.” Escritores, Editoriales y Revistas del Exilio Republicano de 1939, editado por Manuel Aznar Soler, Biblioteca del Exilio/Editorial Renacimiento, 2006, pp. 1723–1763.

- Borel, Jean. “Albert Camus, María Casarès, Correspondance 1944–1959.” Revue de Théologie et de Philosophie, vol. 151, 2, juillet 2019, pp. 180–181.

- Bouvet, Nora Esperanza. La escritura epistolar. Eudeba, 2006.

- Camus, Albert, and Maria Casarès. Correspondance 1944–1959, edited by Catherine Camus, text edited by Béatrice Vaillant, Prologue by Catherine Camus, Gallimard, 2017.

- ———. Correspondance 1944–1959, edited by Catherine Camus, text edited by Béatrice Vaillant, Prologue by Catherine Camus, Folio, 2020.

- Cariguel, Olivier. “L’amour interdit d’Albert Camus et Maria Casarès au grand jour.” Revue des Deux Mondes, Février Mars 2018, pp. 158–60.

- Carpentier, Alejo. “Un libro de memorias. María Casares, Residente privilegiada.” La Vanguardia, 29 de marzo de 1980.

- Casarès, Maria. Résidente privilégiée. Fayard, 1980.

- Casarès, Maria, and Maria Casares. Residente privilegiada. Traducido por Fabián García-Prieto Buendía y Enrique Sordo, Argos Vergara, 1981.

- Casarès, Maria. Residente privilexiada. Traducción de Ana Belén Martínez Delgado, Editorial Trifolium, 2009.

- ———. Residente privilegiada, introducción de María Lopo, traducido por Fabián García-Prieto y Enrique Sordo, Renacimiento, 2022.

- Casarès Maria y Santiago Casares Quiroga. Cartas no exilio. Correspondencia entre Santiago Casares Quiroga e Maria Casares (1946-49), editado por María Lopo, Baía Edicions, 2008.

- Chabot, Jacques. Albert Camus, la pensée du Midi. Edisud, 2002.

- Coca Méndez, Beatriz. “L’expression de la fidélité envers les valeurs noires dans Résidente privilégiée de Maria Casarès.” Crisis: ¿fracaso o reto? Crises: échec ou défi?: Actas del XXIII Congreso de la APFUE (actual AFUE), Universidad de Alcala, 2016, pp. 90–101.

- Delgado, María. “A Spanish actress on the French stage: María Casares.” “Other” Spanish Theatres. Erasure and Inscription on the Twentieth-Century Spanish Stage. Manchester University Press, 2003, pp. 90–131.

- Dusanne, Béatrix. María Casares. Calmann-Lévy, 1953.

- Estévez, Arancha. María Casares. A célebre refuxiada, a descoñecida. Aira, 2022.

- Ezama Gil, Angeles. “Metamorfosis e identidad en la escritura autobiográfica de María Casares.” Bulletin Hispanique, vol. 113–2, 2011, pp. 633–62.

- Fessaget, Dominique. “L’amour fou….1275 pages.” Topique, vol. 147, no. 3, 2019, pp. 29–37.

- Figuero Javier y Marie Hélène Carbonel. Maria Casarès, l’étrangère. Paris, Fayard, 2005.

- Fletcher, John. “Partnership of Equals: Love and Loss in a Quasi-Marriage.” TLC Times Literary Supplement, no. 6018, 3 Aug 2018, pp. 5.

- Foley, John. Albert Camus: From the Absurd to Revolt. Routledge, 2014.

- Grillo, R. M. 1998. “Maria Casares, residente privilegiada en París.” Literatura y cultura del exilio español de 1939 en España, edited by Alicia Alted and Manuel Aznar, Aemic-Gexel, 1998, pp. 119–127.

- Hermida Mondelo, Sabela. Desarrollo artístico de María Casares dentro del marco existencialista francés. Universidad, Rey Juan Carlos de Madrid. Tesis de doctorado, 2013.

- Houvenaghel, Eugenia Helena. ““Entre tú, yo y la carrera: la correspondencia Maria Casarès - Albert Camus (1944–1959).” Anales de Literatura Española Contemporánea, vol. 48, no. 2, 2023, pp. 83–105, núm. 39, In press.

- ———. “Hacia el centro de una refugiada española en Francia: Residente privilégiée de María Casarès.” 80 ans après La Retirada (1939-2019). L’exil républicain espagnol en France: théâtre, culture et engagement. Carnet de Recherche Hypothèses, Les éditions Universitaires d’Avignon, 2021. https://eua.hypotheses.org/5724

- Hughes, Edward J. Albert Camus. Reaktion Books, 2015.

- Iglesia, Ana María. “María Casarès, una gran dama de la escena.” Llanuras. Rutas para lectores, 19 Aug, 2021, llanuras.es/actualidad/maria-casares-una-gran-dama-escena-2/.

- Hylari, Sandrine. “L’heure difficile dans la correspondance entre Albert Camus et Maria Casarès.” Ecritures de soi-R n° 1 « NOCTURNES », october, 2021.

- Kletz-Drapeau, Françoise. “Camus et Casarès s’écrivant pendant le confinement de Camus pour raison de santé: Une correspondance entre séparés.” Société des Etudes Camusiennes, 01 April 2020, etudes-camusiennes.fr.

- Lefebvre, Henri. La Production de l’espace. Anthropos, 1974.

- ———. The Production of Space, 1974. Translated by D. Nicholson-Smith, Basil Blackwell, 1991.

- Libiot, Eric. “Lettres ET LE Néant.” Lire, vol. 483, mar 2020, pp. 24.

- Lopo, María. “A Galicia de Camus.” Grial, vol. 53, no. 205, 2015, pp. 13–21.

- ———. O tempo das mareas. María Casares e Galicia.” Consello da Cultura Gallega, 2016.

- Margerison, Christine editors, et al. Albert Camus in the 21st Century: A Reassessment of His Thinking at the Dawn of the New Millennium. Rodopi, 2008.

- Massey, Doreen. For Space. Key texts in human geography, edited by Ben Anderson, 2008, pp. 227–235.

- ———. Space, Place and Gender. John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

- Merleau Ponty, Maurice. Phénoménologie de la perception. Gallimard, 1945, pp. 339.

- Mourier-Martínez, María Francisca. “Remembranzas de la patria desde el exilio. Residente privilegiada de Maria Casares.” Aymes, Jean-René.” Communautés nationales et marginalité dans le monde ibérique et ibéro-américain, Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 1981, pp. 117–29.

- Neiman, Paul. “Albert Camus’ Philosophy of Love.” Philosophical Investigations, vol. 44, no. 3, July 2021, pp. 318–38.

- Plantagenet, Anne. La única María Casarès. Alba, 2021.

- Roblès, Emmanuel. Camus, frère de soleil. Seuil, 1995.

- Salinas, Pedro. “Defensa de la carta misiva y de la correspondencia epistolar.” Ensayos completos, Tomo 2, Taurus, 1981, pp. 220–93.

- Soler, Joaquín. “María Casares.” Entrevista en a Fondo. Televisión Española, Madrid, 26 de abril de, 1981.

- Stanley, Liz. “The Epistolarium: On Theorizing Letters and Correspondences.” Auto/Biography, vol. 12, 2004, pp. 201–35.

- Todd, Olivier. Albert Camus: une vie.1996. Gallimard, 2010.

- Violi, Patricia. “La intimidad de la ausencia: formas de estructura epistolar.” Revista de Occidente, nrono. 68, 1987, pp. 87–99.

- Violi, Patrizia. “Letters.” Discourse and Literature: New Approaches to the Analysis of Literary Genres, edited by Teun A. van Dijk. John Benjamin Publishing Company, 1985.

- Vircondelet, Alain. Albert Camus, fils d’Alger. Fayar, 2010.

- Westphal, Bernard. La géocritique: Réel, fiction, espace. Les Editions de Minuit, 2007.

- White, Kenneth. Le Plateau de l’Albatros. Grasset, 1994.

- Yaeger Kaplan, Alice. Looking for the Stranger: Albert Camus and the Life of a Literary Classic. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Zambrano, María. La confesión como género literario. Siruela, 2004.