?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Assessing decision-making styles of business students is crucial, particularly in China, because the government increasingly encourages business graduates to establish their own businesses as startups. The authors’ aim was to employ both the Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire and General Decision-Making Style measure to investigate whether differences exist in terms of decision-making styles between students with and without business experience, and whether gender is a moderating factor. The findings will assist in curriculum reform of business education in Chinese universities. More attention should be paid to training students’ decision-making styles, especially the rational style for students without business experience.

Introduction

Business graduates enter the business world and will increasingly encounter a number of problems or dilemmas that cannot be solved with a set answer (Carrithers, Ling, & Bean, Citation2008; Kunsch, Schnarr, & van Tyle, Citation2014). They are expected to employ a wide range of entrepreneurial skills to arrive at logically crafted and high-quality solutions (Li & Persons, Citation2011). Research shows that decision-making style is a crucial entrepreneurial capability of successful business leaders and is perceived as the direct driving forces for economic development (Ivanova & Gibcus, Citation2003).

Even though young business graduates are active in decision making, they usually lack perfect and comprehensive managerial capabilities to cope with a myriad of critical factors. In this regard, the importance of understanding students’ decision-making strategy is evident. Based on this understanding, business education should equip students for future effective decision making in the modern business environment (López-Navarro & Ciprés, Citation2015; Shinnar, Pruett, & Toney, Citation2009).

Yet, little empirical attention has been paid to business students’ decision-making styles in Chinese higher education. Curriculum development has been hindered by knowledge gaps about how students collect and interpret information.

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the decision-making styles of Chinese business students. To close the empirical gap in the previous research, we conducted two studies using different instruments to explore the decision-making styles. We begin with a literature review on previous research about the decision-making skills and an introduction on the Chinese context regarding business education in decision making. The methodology part provides an overview on the sampling methods, the instrument, and the data collection procedure. The research findings are presented subsequently, followed by the conclusion and discussion.

Literature review

Decision making can be defined as a solution that is based on a process of defining alternatives (Certel et al., Citation2013), exploring the available options (Gonzalez & Dutt, Citation2016), analyzing and evaluating copious amounts of information (Kunsch, Citation2014), eliminating the problematic situation (Guelle, Kabadayi, Bostanci, Cetin, & Seker, Citation2014), and formulating flexible action plans (Donovan, Guess, & Naslund, Citation2015).

Decision-making style

According to Scott and Bruce (Citation1995), decision-making style is not a personality trait, but rather refers to a learned, habitual response pattern that an individual tends to show in a decision situation.

Previous research has indicated that adult decision makers tend to have cognitive biases and errors when dealing with complex problems (Ramnarayan, Strohschneider, & Schaub, Citation1997). Fiske and Taylor (Citation1991) put forward that decision makers tend to be “cognitive misers,” minimizing cognitive effort by neglecting nongains or nonlosses in their planning. Brooks (Citation2011) further mentioned that much decision making is just emotional business.

Janis and Mann (Citation1977) have defined two categories of decision-making patterns: adaptive and maladaptive. Adaptive is associated with a moderate level of psychological stress and leads to sound and rational decision making, while maladaptive involves panic, evasiveness, and complacency (Tuinstra, van Sonderen, Groothoff, van den Heuvel, & Post, Citation2000). Adaptive coping strategy refers to vigilance, involving the process of searching for relevant information, deliberating on the alternatives and arriving at the right decision. Vigilance is the key characteristic of a rational decision maker. Vigilant decision makers do not avoid responsibility and hold the belief that there is adequate time to find better alternatives.

The maladaptive strategy is emotion focused. Decision makers characterized by maladaptive strategy tend neither to use relevant information nor to discuss alternatives and attempt to distance themselves from time pressure. The maladaptive styles include hypervigilance, buck-passing, and procrastination. Hypervigilance is associated with severe psychological stress. The decision maker tends to be overwhelmed by emotional pressure, overlooking the full range of issues and having difficulties concentrating.

Buck-passing refers to escaping responsibility and leaving decisions to others. The decision maker prefers to avoid conflict. Procrastination is a tendency to avoid doing less pleasurable or urgent tasks. Procrastination in decision-making is closely associated with students’ tendency to put off academically related tasks (Ferrari, Johnson, & McCown, Citation1995).

While some researchers focus on the four decision-making styles, similar styles with slight differences have also been identified. Scott and Bruce (Citation1995) tested and validated five individual decision-making styles: (a) rational decision makers thoroughly search for and deliberately evaluate alternatives, which can be termed as vigilance; (b) intuitive decision makers rely on own feelings and impressions and tend to make a quick decision, similar to hypervigilance; (c) being dependent refers to those who lack confidence and are likely to rely on the direction and help of others, which is similar to the buck-passing style; (d) being avoidant, similar to procrastination, means that the decision makers are prone to postponing and avoiding decisions; and (e) spontaneous decision makers tend to make snap decisions. Previous research shows that positive career outcomes may be related to rational and intuitive decision-making styles (Crossley & Highhouse, Citation2005).

Hypothesis 1: There is a difference in decision-making styles between decision makers with and without business experience.

One stereotype about gender difference in decision-making styles is that women tend to be more emotionally sensitive because they are more interpersonally oriented whereas men are more self-reliant (Ben-Zeev, Citation2000). Previous research on gender differences in decision-making styles has not reported consistent findings. In 2005, Spicer and Sadler-Smith examined the aforementioned five decision-making styles described by Scott and Bruce (Citation1995) in two independent samples of British business students and noticed that there was no gender difference. Sadler-Smith (Citation2011) further pointed out that it is our stereotype that female university students tend to report more intuitive styles than male students do. This is in line with the findings of Scott and Bruce. However, there is also some evidence that men and women are differentially attuned to decision-making styles (Mau, Citation2000). Certel et al. (Citation2013) examined the decision-making styles of 363 athletes and found a significant gender difference in buck-passing, procrastination, and hypervigilance. Male athletes are more likely to use maladaptive styles than female athletes. Yet, many other studies on university students reveal that there is no significant difference in decision-making styles in terms of gender (e.g. Mau, Citation2000). A survey study among university management students in Australia, conducted by Sinclair, Ashkanasy, and Chattopadhyay (Citation2010), indicated a higher proclivity of female students to be intuitive in decision making, while male students were more analytical. Moreover, women are more inclined to seek support than men do (Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, Citation2002).

Hypothesis 2: There is a gender difference in decision-making styles.

To date, there is no empirical research looking into the interaction effect between gender and business experience regarding decision-making styles, particularly among business students who are the future business practitioners.

Hypothesis 3: There is no gender interaction effect between gender and business experience regarding decision-making styles.

Research justification

In 2015, there were 7.49 million graduates from Chinese higher education but the number of students who were employed decreased. In contrast, the number of fresh business startups by university graduates almost doubled, from 3.2% in 2014 to 6.3% in 2015 (Sun, Citation2016). However, only a small proportion of these startups survived longer than three years. Lacking startup funding (28%), difficulty in market entry (26%), and lack of entrepreneurial skills (24%) constitute the main risks for university graduates’ business startups (Chen & Lin, Citation2015). According to Sun (Citation2016), one plausible explanation is that the traditional Chinese business education tends to ignore the relevant entrepreneurial education such as the training on decision-making skills. On May 4, 2015, the Chinese State Council published its new policy paper on how to boost the incorporation of entrepreneurial training in business education in universities. Previous research explicitly states that the training of decision-making skills plays a significant role in entrepreneurial education. Various factors may impact the entrepreneurial decision-making such as personal background, motivation and social and cultural contexts (Sun, Citation2016).

However, very little empirical research has been conducted to show how Chinese students, the future business practitioners, make decisions and whether a gender difference exists. In 2003, Yi and Park (Citation2003) researched the cultural distinctions in decision-making styles of students from Korea, Japan, China, the United States, and Canada and found that Chinese students tend to be more collaborative but more avoidant when compared with Japanese and American students. Regarding the competitive decision-making style, no difference was detected between them. One point that is worthwhile to mention is that Chinese university students are a very dynamic generation, and findings from 16 years ago may not support our understanding of current business students. To prepare students to cope with future business practices better, it is important to conduct an in-depth study to gauge students’ decision-making styles.

Method

We conducted two studies in one Chinese university located in Hebei Province, the North of China. The university has approximately 8600 undergraduates and 3,300 graduates, which is representative of over 2,000 ordinary (the so-called non-985) universities in China.

Study 1

Sample

Study 1 was conducted in the academic year 2016. In all, 346 students have completed the questionnaires, 107 (30.90%) male students and 239 (69.10%) female students. Students’ age ranged from 18 to 31 years old, with an average age of 21.55 years old (SD = 2.01 years). While 66 participants were graduate students, 280 were undergraduate students.

Instrument

The Melbourne Decision-Making Questionnaire (MDMQ), designed by Mann, Burnett, Radford, and Ford (Citation1997), was adopted in the Study 1, aiming at capturing and measuring the decision-making strategy used. It adheres to Janis and Mann’s (Citation1977) conflict theory that humans are not rational calculators, are easily influenced by intuition, and tend to struggle with doubts, worries, and conflicts (Isaksson, Hajdarevic, Jutterström, & Hörnsten, Citation2014).

The rationale to choose the MDMQ is that it is easily accessible for a large sample in the questionnaire survey. The MDMQ consists of 22 items belonging to four categories: (a) vigilance, (b) hypervigilance, (c) buck-passing, and (d) procrastination. All items are based on 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (not true for me) to 2 (true for me).

Three categories, hypervigilance, buck-passing, and procrastination, represent less effective or rational coping styles, while the vigilance is associated with effective coping styles.

Data collection procedure

The Chinese version of the questionnaire was administered in class by three subject teachers. Students were informed that the questionnaires would only be used for research aims and that data would be processed anonymously. Students were given 20 min to complete the questionnaires, which were then collected by the teachers. This resulted in a high response rate.

Based on the reliability test of subscales in this study, we arrive at the following Cronbach’s alpha values: vigilance (6 items) = .66, hypervigilance (5 items) = .62, buck-passing (6 items) = .76, and procrastination (5 items) = .77. These are in line with the previous research regarding the reliability of the MDMQ (Isaksson et al., Citation2014).

Study 2

Sample

Study 2 was conducted in the academic year 2017, and 244 students completed the questionnaires, of which 83 (34%) were male students and 161 (66%) were female students. In Study 2, we focused on second- and third-year undergraduate students because they are prepared for their final internship in Year 4. Students’ average age was 20.32 years old (SD = 0.94 years).

Instrument

To accurately measure students’ decision-making styles, we used the General Decision-Making Style (GDMS) measure developed by Scott and Bruce (Citation1995). Using two different instruments in Studies 1 and 2 facilitates our comparison of the findings to grasp students’ decision-making styles more precisely. Besides, the GDMS measure has high levels of internal consistency and has been validated because it is more encompassing than other decision style scales (Loo, Citation2000; Salo & Allwood, Citation2011; Spicer & Sadler-Smith, Citation2005).

The GDMS instrument contains 25 five-point Likert-type scale questions, focusing on five styles: (a) avoidant, (b) dependent, (c) intuitive, (d) rational and (e) spontaneous. Each style consists of five questions.

For both the MDMQ and GDMS measure, the questionnaire was translated into Chinese and then back-translated into English to ensure the message conveyed stayed the same. To test whether the translated instruments would be suitable in a Chinese context, a pilot study was conducted among a convenience sample of 20 Chinese business students. After discussions with experts on behavioral science research, some minor changes in the wording of some items between the English and the translated Chinese were made.

Data collection procedure

Unlike the paper-based questionnaire in Study 1, students were invited to fill in the questionnaire online, using their smartphones. Chinese researchers, also the subject teachers, shared the QR code during class and students used their class break to complete the questionnaire. Completing the GDMS took around 15 min. All data were processed anonymously.

In terms of the coefficients of internal consistency, we arrive at the following Cronbach’s alpha values: rational (5 items) = .79, intuitive (5 items) = .68, dependent (5 items) = .68, avoidant (5 items) = .69, and spontaneous (5 items) = .74. These are consistent with the reliability test of the research by Spicer and Sadler-Smith (Citation2005).

Results

Descriptive analysis

In both studies, we asked respondents whether they had business experience. In the questionnaires, we briefly introduced what is meant by business experience. The detailed descriptive analysis of the results is tabulated in . In Study 1, approximately half of Chinese students (n = 182, 52.45%) reported to have some business experience, and significantly more male students were involved in business than female students, In Study 2, less than half of the students had business experience (n = 105, 43.30%). One plausible explanation is that we focused on Year 2 and 3 undergraduate students and did not include graduate students in Study 2. Again, there was a gender difference in terms of business experience,

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of business experiences regarding gender.

Hypothesis testing: Study 1

In Study 1, the MDMQ (Mann et al., Citation1997) was employed, containing the four decision-making styles: vigilance, hypervigilance, buck-passing and procrastination, see . The one-way analysis of variance shows a significant difference in vigilance, F(2, 344) = 15.43, p < .001. Students with business experience are more featured by vigilance in decision making, being more rational and not beset by pressure or emotions. As for the buck-passing strategy, there is also a significant difference, F(2, 344) = 9.91, p < .001. For procrastination, there is a tendency for students without the willingness to establish their business to demonstrate procrastination, F(2, 343) = 2.53, p = .081. For hypervigilance, there is no significant difference, F(2, 344) = 1.22, p = .296.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations of decision-making styles regarding gender.

In presents the means and standard deviations of decision-making styles of female and male students in both studies.

Table 3. Means and standard deviations of decision-making styles.

There was a significant gender difference in vigilance style, t(345) = 2.59, p = .010, Cohen’s d = 0.30. Female students showed more a vigilant style than male students did. For the remaining decision-making styles, there was no significant difference between male and female students.

The third research question concerns the interactive effect of business experience and gender on decision-making styles. In Study 1, no statistically significant interaction effect is detected using the two-way analysis of variance test (p > .05).

Hypothesis testing: Study 2

In Study 2, we use the GDMS questionnaire developed by Scott and Bruce (Citation1995). Five decision-making styles were identified: rational, intuitive, avoidant, dependent, and spontaneous.

First, results show that students’ business experience is significantly related to three decision-making styles: rational, dependent and spontaneous. Students with business experience are significantly more rational than those without business experience, F(2, 241) = 13.67, p < .001. In contrast, students without any business experience are significantly more dependent, F(2, 241) = 5.08, p = .007, and more likely to make spontaneous decisions, F(2, 241) = 3.48, p = .032. For the intuitive and avoidant decision-making styles, there was no significant difference,

Regarding the gender difference, the independent samples t test showed that male students demonstrated significantly more intuitive styles than female students did, t(242) = 3.23, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 0.44, while female students were more dependent than male students were, t(242) = −3.34, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 0.46. As for the rational style, at the 95% confidence level, the gender difference was not significant, t(242) = −1.73, p = .086, Cohen’s d = 0.21. It seems that female students tend to be more rational than male students are. For the spontaneous and avoidant styles, no significant gender difference was found.

For our third hypothesis, we examined whether there is an interaction effect of business experience and gender on students’ decision-making styles using two-way ANOVA analysis in Study 2.

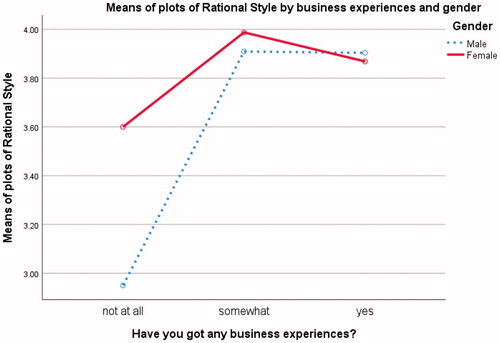

For rational style, the main effect for gender, F(1, 238) = 5.51, p < .01, as well as the main effect for business experience, F(2, 238) = 24.35, p < .01, were significant at the .05 level. The partial eta-squared (η2), a strength of relationship index, was small in size for the effect of gender (.02), but was strong for business experience (.17). In addition, as shown in , there is a significant interaction effect, F(2, 238) = 6.36, p < .01, partial η2 = .05. The follow-up analysis shows that male students with business experience tend to be more rational than are those without business experience, F(2, 80) = 15.72, p < .01. Based on the post hoc analysis, the main difference exists between female students without any business experience and the other two groups, those with somewhat or more experience (Mdiff = −0.39, p = .04, and Mdiff = −0.27, p = .04, respectively). In other words, female students tend to be more rational than male students when they do not have business experience. But with increasing business experience, male students tend to be equally rational as the female students.

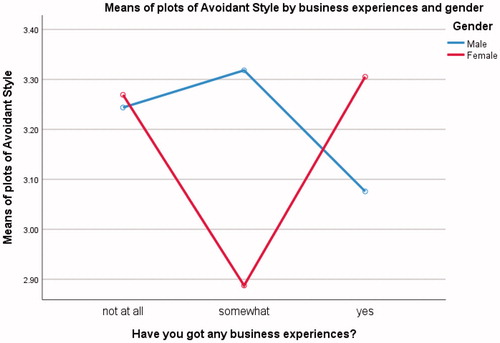

The same interaction effect has been found for avoidant style by students’ business experience and their gender, F(2, 238) = 3.59, p = .03, partial η2 = .03. As shows, with the increase of business experience, female students tend to be more avoidant than male students. For the other decision-making styles, there is no significant interaction effect, p > .05.

Discussion

The aim of the present research is to gain insights into the decision-making styles of Chinese business students. Despite the abundance of research in decision-making styles in the past years, most researchers focus on American or European students. In Chinese business education, research is scare in this regard, and we believe that findings of this research may facilitate business lecturers and curriculum designers to refine the traditional framework of business education in China.

The present research consists of two survey studies, and the MDMQ (Mann et al., Citation1997) and GDMS measure (Scott & Bruce, Citation1995) are employed to gauge the decision-making styles of Chinese business students in a representative university. We first investigated the difference between students with and without business experience regarding their decision-making styles. The analysis showed that business experienced students are more rational and vigilant as decision makers, and less impetuous or dependent on others.

Kearney (Citation2013) posited that the traditional business curriculum is founded around the notion that business students are rational individuals, able to collect information and to make rational choices. Our findings challenge this rationale. Most university students, especially undergraduate students, lack business experience, and tend to avoid or postpone decisions, be dependent on others, or make more spontaneous decisions.

As mentioned previously, the Chinese government keeps encouraging university students to start up their own business upon graduation. Given the fact that at least one fifth of Chinese startups cannot survive over three years due to the weak entrepreneurial skills (Chen & Lin, Citation2015), business education of universities faces a new challenge to incorporate the training of decision-making styles into traditional curriculum. For both Study 1 and Study 2, it can be noticed that around half of the students have absolutely no business experience. Hence, training of being a rational decision maker seems particularly essential now.

Regarding the gender difference in decision-making styles, we have found that female students are more dependent than male students and are more willing to seek help from others. This is in line with some previous research such as the meta-analysis by Tamres et al. (Citation2002). However, we also found that male students are more likely to rely on intuition instead of analytical thinking, as compared with female students. This finding from Chinese students echoes Sadler-Smith’s (Citation2011) claim that the stereotype of female intuition has no strong empirical support.

In terms of the interaction effect of business experience and gender, it is interesting to note that women tend to benefit more from business practices than men. Having business experience may help women become more rational and more deliberate in decision making. It is also safe to conclude that the business experience may minimize the gender gap as a rational decision maker. However, our study also points out that among Chinese university students significantly more men than women are experienced in business.

Another interesting finding is the interaction effect found in avoidant style. When both female and male students lack business experience, they show a high tendency to avoid conflicts or urgent tasks. However, with somewhat business experience, women are significantly less avoidant than men are. This noticeable change makes them excel the male counterparts and become accountable for the tasks. Owing to the limited sample size of business experienced students and lack of qualitative exploratory study on students’ perception of business experience, it is risky for us to postulate an explanation for this finding. We suggest that future researchers explore what female and male students have learned from their business experience and how this is associated with their decision-making styles.

Insights gleaned from our research can inform discussions among business curriculum designers about how to train university students effectively. All in all, we suggest that gender difference and the interaction effect between gender and business experience of students be considered in curriculum design. Yet, in Chinese higher education, the business curriculum is always designed as a panacea for all, ignoring the students’ prior experience. It is worthwhile to discuss how to tailor the curriculum to personal experience and distinguish female and male students’ decision-making styles.

The practical implication of this research is to provide empirical evidence to curriculum designers or business lecturers in Chinese universities, and to call their attention to the challenges. Inevitably, our research has some limitations. First of all, this study seems to be the first to use the Chinese translation of MDMQ. We have noticed that the reliability coefficients of subscales of MDMQ are relatively low in comparison with GDMS. Although they are roughly in concert with the previous tests, we plan to re-examine the Chinese translation and refine the wordings if the MDMQ needs to be reused. Second, the university where the current research is conducted is a non-985 university. In China, 41 universities are labeled as “985 project” and are the pioneers in education reform. We suggest that future researchers include 985 universities as well as the non-985 universities to achieve a more comprehensive and representative sample. Last, Spicer and Sadler-Smith (Citation2005) set forth that self-report questionnaires are not always the most accurate means of assessment of decision-making styles. Bias and distortion cannot be completely avoided. A mixed-research method is preferable in terms of validity of the research.

References

- Ben-Zeev, A. (2000). The subtlety of emotions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Brooks, D. (2011). The Social Animal. London, UK: Random House.

- Carrithers, D., Ling, T., & Bean, J. C. (2008). Messy problems and lay audiences: Teaching critical thinking within the finance curriculum. Business Communication Quarterly, 71(2), 152–170. doi:10.1177/1080569908318202

- Certel, Z., Aksoy, D., Çalışkan, E., Lapa, T. Y., Özçelik, M. A., & Çelik, G. (2013). Research on self-esteem in decision making and decision-making styles in taekwondo athletes. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 1971–1975. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.150

- Chen, G. X., & Lin, J. (2015). Annual report of Chinese business startups. Rungain Think Tank of Enterpreneurship. Retrieved from on Oct 22, 2017. http://www.yemacaijing.com/Index/view/id/173.html

- Crossley, C. D., & Highhouse, S. (2005). Relation of job search and choice process with subsequent satisfaction. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26(2), 255–268. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2004.04.001

- Donovan, S. J., Guess, C. D., & Naslund, D. (2015). Improving dynamic decision making through training and self-reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 10(4), 284–295.

- Ferrari, J. R., Johnson, J. L., & McCown, W. G. (1995). Procrastination and task avoidance: Theory, Research, and Treatment. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science and Business Media.

- Fiske, S., & Taylor, S. (1991). Social cognition. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Gonzalez, C., & Dutt, V. (2016). Exploration and exploitation during information search and consequential choice. Journal of Dynamic Decision Making, 2, 1–8. doi:10.11588/jddm.2016.1.29308

- Guelle, M., Kabadayi, M., Bostanci, O., Cetin, M., & Seker, R. (2014). Evaluation of the correlation between decision-making styles and burnout levels of the team-trainers who competed in regional amateur league. Procedia-Social and Behaviroal Sciences, 152, 483–487.

- Isaksson, U., Hajdarevic, S., Jutterström, L., & Hörnsten, A. (2014). Validity and reliability testing of the Swedish version of Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(2), 405–412. doi:10.1111/scs.12052

- Ivanova, E., & Gibcus, P. (2003). The Decision-Making Entrepreneur: Literature Review, SCALESpaper N200219, EIM Business & Policy Research.

- Janis, I. L., & Mann, L. (1977). Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice and commitment. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Kearney, C. (2013). Business education in Asia and Australasia: Recent trends and future prospects. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 24(3–4), 214–227. doi:10.1080/08975930.2013.860351

- Kunsch, D. W., Schnarr, K., & van Tyle, R. (2014). The use of argument mapping to enhance critical thinking skills in business education. Journal of Education for Business, 89(8), 403–410. doi:10.1080/08832323.2014.925416

- Li, S. F., & Persons, O. S. (2011). Cultural effects of business students’ ethical decision: A Chinese versus American comparison. Journal of Education for Business, 86(1), 10–16. doi:10.1080/08832321003663330

- Loo, R. (2000). A psychometric evaluation of the General Decision-Making Style Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(5), 895–905. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00241-X

- López-Navarro, M. A., & Ciprés, M. S. (2015). Social issues in business education: A Study of Students' Attitudes. Journal of Education for Business, 90(6), 314–321. doi:10.1080/08832323.2015.1046360

- Mann, L., Burnett, P., Radford, M., & Ford, S. (1997). The Melbourne Decision Making Questionnaire: An instrument for measuring patterns for coping with decisional conflict. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 10(1), 1–19. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(199703)10:1<1::AID-BDM242>3.0.CO;2-X

- Mau, W. C. (2000). Cultural differences in career in career decision-making styles and self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 57(3), 365–378. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1999.1745

- Ramnarayan, S., Strohschneider, S., & Schaub, H. (1997). The trappings of expertise and the pursuit of failure. Simulation and Gaming, 28(1), 28–44. doi:10.1177/1046878197281004

- Sadler-Smith, E. (2011). The intuitive style: Relationships with local/global and verbal/visual styles, gender, and superstitious reasoning. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(3), 263–270. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2010.11.013

- Salo, I., & Allwood, C. M. (2011). Decision-making styles, stress and gender among investigators. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management, 34(1), 97–119. doi:10.1108/13639511111106632

- Scott, S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1995). Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55(5), 818–831. doi:10.1177/0013164495055005017

- Shinnar, R., Pruett, M., & Toney, B. (2009). Entrepreneurship education: Attitudes across campus. Journal of Education for Business, 84(3), 151–159. doi:10.3200/JOEB.84.3.151-159

- Sinclair, M., Ashkanasy, N. M., & Chattopadhyay, P. (2010). Affective antecedents of intuitive decision making. Journal of Management and Organization, 16, 382–398.

- Spicer, D. P., & Sadler-Smith, E. (2005). An examination of the general decision making style questionnaire in two UK samples. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2), 137–149. doi:10.1108/02683940510579777

- Sun, W. (2016). Training of university students’ entrepreneurial decision-making ability echoing the reform of supply side—based on analysis on the model of E-PCI-S psychological capital intervention. Chinese Journal of Education for Entrepreneurschip, 7(3), 17–22.

- Tamres, L. K., Janicki, D., & Helgeson, V. S. (2002). Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 2–30. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1

- Tuinstra, J., van Sonderen, F. L. P., Groothoff, J. W., van den Heuvel, W. J. A., & Post, D. (2000). Reliability, validity and structure of the adolescent decision making questionnaire among adolescents in the Netherlands. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(2), 273–285. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00096-3

- Yi, J. S., & Park, S. (2003). Cross-cultural differences in decision-making styles: A study of college students in five countries. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 31(1), 35–48. doi:10.2224/sbp.2003.31.1.35