?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper calculates the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on educational outcomes for undergraduate business programs in Mexico. We use administrative data from the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education and a difference-in-differences empirical strategy to estimate the impact. We find a negative effect on intake, enrollment, and graduation outcomes. We also examine heterogeneous effects, showing that top business schools increased the number of intakes with respect to non-top schools. Furthermore, public schools were more negatively impacted than private schools in terms of graduation outcomes, while synchronous-learning programs reported a higher decrease on graduation rates than asynchronous-learning programs.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted nearly 1.6 billion students around the world across all levels of education (United Nations, Citation2020). In the United States, for instance, undergraduate enrollment for business majors fell by 4.3% (67,665 students) between 2019 and 2021 (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center [NSCRC], Citation2022). The interruption of in-person instruction, the shocks in household income due to a series of lockdowns, as well as the deterioration in mental health, all had an effect on students’ learning outcomes, enrollment, and dropouts. According to Azevedo, Gutierrez, de Hoyos, and Saavedra (Citation2022), the impact of the pandemic on educational outcomes was heterogeneous across gender, socioeconomic status, and the source of school revenue.

In this paper, we analyze the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on educational outcomes for undergraduate business programs in Mexico. We use administrative data from the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education (ANUIES). The ANUIES data report timely information for intake, enrollment, and graduation outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to calculate the impact of the pandemic on educational outcomes for business schools in Mexico. Our findings make two contributions to the existing literature. First, our results add to an increasing literature showing detrimental effects of the pandemic on educational outcomes such as intake, enrollment, and graduation rates (Chatterji & Li, Citation2021; NSCRC, Citation2022; Rana, Anand, Prashar, & Haque, Citation2022). Second, we document heterogeneous effects of the pandemic, which are important to understand potential sources of education inequalities in developing countries.

Undergraduate business education and the COVID-19 pandemic

Even though the actual impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on educational outcomes in business schools remains to be estimated, the existing literature identifies the main challenges that business schools faced as a consequence of the pandemic. Namely, business schools adapted their educational model by offering online classes to students enrolled in undergraduate synchronous-learning (in-person) programs, in order to comply with the stay-at-home orders that were launched to contain the spread of the novel virus. Such model changed the value proposition of business schools at the individual and at the institutional levels (Laasch, Ryazanova, & Wright, Citation2022).

At the individual level, the unexpected shift in value proposition brought many losses in terms of pedagogy and scholarship (Greenberg & Hibbert, Citation2020). Pedagogical losses came in the form of interruptions of the archetypal roles used by educators such as lectures and experiential activities, making business education less dynamic (Pasion, Dias-Oliveira, Camacho, Morais, & Franco, Citation2021; Ryazanova, Wright, & Laasch, Citation2021). Business scholarship also suffered because faculty members confined at home, losing the opportunity to travel to academic conferences or to exchange ideas in-person with other scholars (Greenberg & Hibbert, Citation2020).

At the institutional level, the pandemic brought several challenges including financial hardship, deglobalization, and the exclusion of certain community members. The shortfall of tuition fees—and tax-funded budgets—froze investments and faculty hiring in most schools (Marinoni, Van’t Land, & Jensen, Citation2020). In terms of deglobalization, travel restrictions—imposed to contain the spread of the COVID-19 virus—affected in-person scientific exchanges and the flow of international students (Schlegelmilch, Citation2020). Finally, certain groups of the academic community, particularly women, bore much of the cost of the pandemic because childcare was not available, which ultimately excluded these members from important professional activities (Amis, Brickson, Haack, & Hernandez, Citation2021; Burzynska & Contreras, Citation2020).

There is an increasing number of papers analyzing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on educational, health, and economic outcomes for college students. Education-wise, the pandemic decreased enrollment (Bulman & Fairlie, Citation2021) and course completion (Bird, Castleman, & Lohner, Citation2022; De Paola, Gioia, & Scoppa, Citation2022). The pandemic also increased the number of students withdrawing or consider withdrawing from college (Aucejo, French, Ugalde, & Zafar, Citation2020; Jaeger et al., Citation2021; Michel et al., Citation2021; Rodr´ıguez-Planas, Citation2022), as well as of those delaying graduation (Aucejo et al., Citation2020; Finamor, Citation2022; Rodr´ıguez-Planas, Citation2022). Furthermore, college students increased hours devoted to schoolwork in around 10% (Liao, Abukhalaf, & Powell, Citation2022). In terms of course grades, the evidence for the impact of the pandemic is mixed: some papers point to lower course grades (Kofoed, Gebhart, Gilmore, & Moschitto, Citation2021; Orlov et al., Citation2021), while others, to higher scores (Engelhardt, Johnson, & Siemers, Citation2022; Karada˘g, Citation2021). Health-wise, the pandemic affected the mental health of college students (Aristovnik, Keržič, Ravšelj, Tomaževič, & Umek, Citation2020; Harries et al., Citation2021), while, at the same time, opened an opportunity to do more exercise and to eat healthy (Logel, Oreopoulos, & Petronijevic, Citation2021). Finally, the pandemic had a negative effect on income for college students graduating in times of COVID-19 (Messacar, Handler, & Frenette, Citation2021).

Notwithstanding the literature’s identification of the main challenges for business schools, there remains a knowledge gap for quantifying the pandemic’s impact on educational outcomes. That is, we still do not know how the pandemic affected intake, enrollment, and graduation rates in business schools. This is extremely important because we must first understand the damage and the educational inequalities caused by the pandemic in order to formulate new value propositions for business schools.

Materials

In this paper, we use administrative data gathered by the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education (ANUIES) in Mexico. ANUIES gathers data on all higher education institutions in Mexico. The data includes intake, enrollment, and graduation statistics at the level of academic programs for every campus of every institution. Information is decomposed by academic year from 2010 to 2021.Footnote1 Our data also includes institutional characteristics such as whether the university is public or private, and the delivery of the program, which can be synchronous-learning (e.g., all in-person studies) or asynchronous-learning (self-study delivery). We restrict our analysis to the academic years of 2017–2018, 2018–2019, 2019–2020, and 2020–2021, and to business majors, exclusively.

presents summary statistics for the pre-COVID-19 (academic years corresponding to 2017–2018, 2018–2019, 2019–2020) and post-COVID-19 periods (academic year corresponding to 2020–2021). All units correspond to the number of students. Before the start of the pandemic, on average, 89.87 students entered undergraduate business programs at each campus of every higher institutions in Mexico. The average undergraduate business program enrollment during the pre-COVID-19 period is 338.05 students, while the average number of students graduating is 36.18 students. Footnote2 Just as in many other countries, the number of students graduating is much lower than the number of students entering a business program at the undergraduate level. This is due to two main factors: (i) a high dropout rate, and (ii) the hazardous process to complete the final paperwork with the Ministry of Education.Footnote3

Table 1. Summary statistics.

Methodology

Difference-in-difference

We use a difference-in-differences methodology to study the impact of the pandemic on educational outcomes for business programs in Mexico. The difference-in-differences specification is as follows:

(1)

(1)

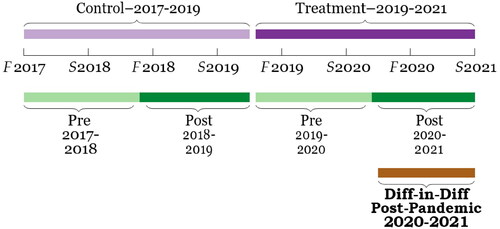

where Ycsmy denotes the educational outcome in campus c of school s, in municipality m, and academic year y. Treatmentmy stands for a dummy variable that takes the value of one for treated schools—each campus of every institution during the academic years 2019–2020 and 2020–2021—, and zero for the control schools—each campus of every institution during the academic years 2017–2018 and 2018–2019. Postmy is a dummy variable that takes the value of one for the post period—academic years 2018–2019 and 2020–2021—, and zero for the pre period—academic years 2017–2018 and 2019–2020—, essentially creating a time-frame that allows us to compare the average change in the treatment period with the pre-post change in the control period. Finally, Xcsmy correspond to campus characteristics; specifically, we control for the delivery of the business program, the source of revenue, and whether the university is within the top 20 business schools in Mexico.

depicts this difference-in-differences strategy, visually. The control group period corresponds to the light purple bar (academic year in the period 2017–2019), while the treatment group period, the dark purple bar (academic year in the period 2019–2021). All academic years contain two terms: fall (F) and spring (S). Within the control and the treatment group, the dark green bars depict the post-period, while the light green bars do so for the pre-periods. The main period of interest is the dark brown bar. This dark brown area captures the COVID-19 pandemic for the academic year 2020–2021, and considers the change in educational outcomes for business schools over the treatment period relative to the pre-post change in the control group.

Difference-in-difference-in-difference

To further estimate the differential impact of the pandemic on institutional characteristics, we implement a triple difference-in-differences (DDD) approach. Hence, we adjust the previous estimation as follows:

(2)

(2)

where Hetcsmy denotes a dummy variable equal to one if the campus c of the business school s belongs to a sub-group in consideration. We study heterogeneous effects of the pandemic by delivery (synchronous-learning vs asynchronous-learning programs), source of school revenue (public vs private), elite status (top 20 vs non-top 20 schools), and accreditation status (AACSB-accredited vs non-AACSB-accredited).

Findings

Main results

presents the difference-in-differences results, following the mathematical specification in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . We find large effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on intake and graduation outcomes for undergraduate business programs in Mexico (Columns 1 and 3); namely, our coefficients suggest a decrease of 16.28 students and 6.8 students, respectively. These effects are in the order of −18%, relative to the pre-COVID-19 mean.

Table 2. Difference-in-differences.

Column (2) of contains the pandemic’s impact on enrollment for undergraduate business programs in Mexico. The coefficient for this educational outcome is small, representing a decrease of only −3%, relative to the pre-COVID-19 mean. The small effect on enrollment—in comparison to the large drop in the number of students graduating—, suggests that undergraduate business students either enrolled in fewer courses or delayed the official process with the Ministry of Education. Although not shown in our results, we find no effect of the pandemic on the number of students completing all coursework requirements. The previous implies that the main decrease on graduation rates may be originating from bottlenecks in Mexico’s bureaucratic apparatus.Footnote4

Heterogeneous treatment effects

shows heterogeneous treatment effects by institutional characteristics, as formally specified in EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) . We consider the pandemic’s effect by program delivery, source of school revenue, elite status, and accreditation status. Each panel of contains a particular heterogeneous treatment effect.

Table 3. Heterogeneous treatment effects.

Panel A presents the pandemic’s heterogeneous effect for synchronous-learning programs compared to asynchronous-learning. Unexpectedly, we do not find a difference on the pandemic’s effect on intake and enrollment outcomes for synchronous-learning programs relative to asynchronous-learning. The absence of a differential effect on intake and enrollment outcomes may be due to business schools adapting educational models or to students forecasting a short duration of the pandemic. Conversely, we find a heterogeneous effect on the number of students graduating. Relative to asynchronous-learning programs, synchronous-learning programs present a decrease in graduation rates equal to 6.38 students (14%). That is, business programs processing graduation paperwork online were significantly less affected than in-person programs, which had to adjust institutional procedures to obtain official diplomas from the Ministry of Education.

In panel B, we report results by source of school revenue (public vs private). We do not find heterogeneous effects on intake and enrollment outcomes. On the contrary, public institutions report a larger decrease on graduation rates than private institutions, in the order of −26.4%. Although not shown here, we do not find a heterogeneous effect on the number of students fulfilling all coursework requirements, meaning that private business schools adapted institutional procedures to obtain official diplomas faster than public business schools, during the pandemic.

Panel C contains differential effects on intake, enrollment, and graduation outcomes by elite status. We define a business school as an elite institution if it places within the top 20 of the QS University Ranking for Mexico. Coefficient for intake and enrollment outcomes show a positive impact of the pandemic for the elite group of Mexican business schools equal to 18% and 3%, relative to the pre-COVID mean. Indeed, top business schools in Mexico have more resources, which may induce business students to choose institution best able to cope with the crisis. In terms of graduation outcomes, we do not find differential effects by elite status.

Finally, Panel D presents the pandemic’s heterogeneous effects by AACSB-accreditation holding status. Only four business schools in Mexico hold an AACSB accreditation at the undergraduate level. Contrary to our expectations, we do not find a differential effect of the pandemic by accreditation status. This null effect applies to intake, enrollment, and graduation outcomes.

Robustness test

We verify the validity of our findings by conducting two robustness checks. First, we run a placebo test to corroborate the parallel trends assumption of the difference-in-differences methodology. Second, we conduct a correction for multiple hypothesis testing. Neither test invalidates our main results.

We run a placebo test to verify that the results are driven by the COVID-19 pandemic and not due to unobservable trends in either the treatment or control group. Specifically, we recalculate the difference-in-difference estimator, assuming that the pandemic hit Mexico one year earlier (March 2019 instead of March 2020). We use each of the academic years between 2016–2017 and 2019–2020, and re-define the treatment group to be the 2018–2019 and 2019–2020 academic years, and the control group to be the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 academic years. Similarly, we re-define the post-period and the pre-period to be the 2017–2018 and 2019–2020 academic years, and the 2016–2017 and 2018–2019 academic years, respectively. in Appendix A of this paper presents the results of the placebo test. As expected, the difference-in-difference coefficients are statistically insignificant for all educational outcomes.

To correct for multiple hypothesis testing, we use the sharpened False Discovery Rate q-values as suggested by Anderson (Citation2008). The results are presented in in Appendix A. Reported in parenthesis are the p values of , and below them, in brackets, the q-values. None of the statistically significant results becomes not significant when adjusting the p values for multiple hypothesis testing. Therefore, our results are indeed statistically driven by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion and recommendations for additional research

We suggest the following mechanisms for this study’s findings: (a) lack of income, (b) fear of infection, (c) mental health, (d) school closures, and (e) availability of educational services. Unfortunately, our data is limited in scope and does not let us test any of these proposed mechanisms. Future research should analyze any or all of these mechanisms as potential drivers of the pandemic’s impact on educational outcomes. New literature should warrant the distributional effects of these potential mechanisms. Future studies should also analyze the pandemic’s impact on progression to the labor market, once students’ graduate. Ideally, such studies should use school administrative data at the student-level.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the need of a new value proposition to make business schools more attractive than ever (Laasch et al., Citation2022; Ritter & Pedersen, Citation2020). Theoretically-speaking, the socialization of a pandemic—an outside crisis that provokes change to address issues that affect institutions or the society at large—should push all kinds of institutions and societies to formulate new value propositions (Alexander, Citation2018). Business educators, likewise, should “strive for a new and better normal” (Brammer, Branicki, & Linnenluecke, Citation2020, p. 501). This new value proposition should consider grade deflation, budget constraints, management competences, multidisciplinary research, and online education as crucial elements (Beech & Anseel, Citation2020; Bunch, Citation2020).

Coming up with a new value proposition for business schools under the current situation requires allostatic leadership (Fernandez & Shaw, Citation2020). This type of leadership should empower, involve, and promote collaboration in a network of teams to come up with innovating solution that bring value to all (Fernandez & Shaw, Citation2020). In essence, business schools’ administrators should not let this crisis go to waste, bringing new value propositions that advance business education. As we quantify the damage and the learning gap that we are facing, we should push for innovative solutions that bring value to all members of business schools.

Conclusions

In this paper, we document the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on educational outcomes for undergraduate business programs in Mexico. We use administrative data from the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education and a difference-in-differences empirical strategy to estimate the impact. We find a negative effect on intake (−18.1%), enrollment (−3.4%), and graduation (−18.9%) outcomes.

The findings in this study present timely information for business schools’ administrators to take strategic action. The COVID-19 pandemic made even more evident the need of a new value proposition for business schools. Quantifying the pandemic’s damage should provide leaders of business schools with a broader perspective of the grand challenges ahead for the advancement of business education, including inequalities and educational outcomes.

Finally, we only focus on business schools at the undergraduate level, even though heterogeneous effects could be observed for different majors and levels of education. For instance, the pandemic may have changed students’ preferences for majors. Likewise, under weak labor market conditions, recently unemployed graduates may choose to enroll in graduate studies to invest in their human capital while waiting for better labor market conditions. This inquiries about the pandemic’s effects on business education remain unexplored.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Mendeley Data repertory, with reference number 17632 and with DOI 10.17632/pdyd8nyn7y.1. Our database comes from the following resources available in the public domain: ANUIES, Anuarios Estad´ısticos de Educacíon Superior, http://www.anuies.mx/informacion-y-servicios/informacion-estadistica-de-educacion-superior/anuario-estadistico-de-educacion-superior.

Notes

1 The academic year in Mexico runs from August to May.

2 In Mexico, after completing all coursework, there is a final process to validate the diploma with the Ministry of Education (SEP).

3 On average, around 51 students complete all coursework required to graduate, but only 36 students complete the paperwork with the Ministry of Education in order to receive their business diploma.

4 We conduct these same analyses by gender. Results by gender are similar to the overall effects for intake and graduation outcomes, but not for enrollment outcomes, with men bearing most of the impact on enrollment rates. These results are available from the authors upon request.

References

- Alexander, J. C. (2018). The societalization of social problems: Church pedophilia, phone hacking, and the financial crisis. American Sociological Review, 83(6), 1049–1078. doi:10.1177/0003122418803376

- Amis, J., Brickson, S., Haack, P., & Hernandez, M. (2021). Taking inequality seriously. Academy of Management Review, 46(3), 431–439. doi:10.5465/amr.2021.0222

- Anderson, M. L. (2008). Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early intervention: A reevaluation of the abecedarian, Perry preschool, and early training projects. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(484), 1481–1495. doi:10.1198/016214508000000841

- Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 8438. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/20/ doi:10.3390/su12208438

- Aucejo, E., French, J., Ugalde, P., & Zafar, B. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104271. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271

- Azevedo, J. P., Gutierrez, M., de Hoyos, R., & Saavedra, J. (2022). The unequal impacts of COVID-19 on student learning. In F. M. Reimers (Ed.), Primary and secondary education during COVID-19: Disruptions to educational opportunity during a pandemic (pp. 421–459). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4

- Beech, N., & Anseel, F. (2020). COVID-19 and its impact on management research and education: Threats, opportunities and a manifesto. British Journal of Management, 31(3), 447–449. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12421

- Bird, K. A., Castleman, B. L., & Lohner, G. (2022). Negative impacts from the shift to online learning during the COVID-19 crisis: Evidence from a statewide community college system. AERA Open, 8, 233285842210812. doi:10.1177/23328584221081220

- Brammer, S., Branicki, L., & Linnenluecke, M. K. (2020). Covid-19, societalization, and the future of business in society. Academy of Management Perspectives, 34(4), 493–507. doi:10.5465/amp.2019.0053

- Bulman, G., & Fairlie, R. W. (2021, April). The impact of COVID-19 on community college enrollment and student success: Evidence from California administrative data (Working Paper No. 28715). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w28715

- Bunch, K. J. (2020). State of undergraduate business education: A perfect storm or climate change? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 19(1), 81–98. doi:10.5465/amle.2017.0044

- Burzynska, K., & Contreras, G. (2020). Gendered effects of school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 395(10242), 1968. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31377-5

- Chatterji, P., & Li, Y. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 on school enrollment. Economics of Education Review, 83, 102128. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102128

- De Paola, M., Gioia, F., & Scoppa, V. (2022). Online teaching, procrastination and students’ achievement: Evidence from COVID-19 induced remote learning. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–36. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4114561

- Engelhardt, B., Johnson, M., & Siemers, S. (2022). Business school grades, assessment scores, and course withdrawals in the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education for Business, 0(0), 1–17. doi:10.1080/08832323.2022.2109563

- Fernandez, A. A., & Shaw, G. P. (2020). Academic leadership in a time of crisis: The coronavirus and COVID-19. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(1), 39–45. doi:10.1002/jls.21684

- Finamor, L. (2022). Labor market conditions and college graduation. arXiv. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.11047

- Greenberg, D., & Hibbert, P. (2020). From the editors—COVID-19: Learning to hope and hoping to learn. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management.

- Harries, A. J., Lee, C., Jones, L., Rodriguez, R., Davis, J., Boysen-Osborn, M., … Juarez, M. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students: A multicenter quantitative study. BMC Medical Education, 21, 14. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02462-1

- Jaeger, D. A., Arellano-Bover, J., Karbownik, K., Mart´ınez-Matute, M., Nunley, J., Seals, R. A., … Zhu, M. (2021, June). The global COVID-19 student survey: First wave results [IZA Discussion Paper 14419]. Retrieved from https://covid-19.iza.org/ de/publications/dp14419/

- Karada˘g, E. (2021, August). Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on grade inflation in higher education in turkey. PLoS One, 16(8), e0256688. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256688

- Kofoed, M., Gebhart, L., Gilmore, D., & Moschitto, R. (2021). Zooming to class?: Experimental evidence on college studentsamp;apos; Online learning during COVID-19. Retrieved from https://europepmc.org/article/PPR/PPR422486

- Laasch, O., Ryazanova, O., & Wright, A. L. (2022). Lingering COVID and looming grand crises: Envisioning business schools’ business model transformations. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 21(1), 1–6. doi:10.5465/amle.2022.0035

- Liao, W., Abukhalaf, R., & Powell, J. W. (2022). COVID-19’s effect on study hours for business students transitioning to online learning. Journal of Education for Business, 0(0), 1–8. doi:10.1080/08832323.2022.2103488

- Logel, C., Oreopoulos, P., & Petronijevic, U. (2021, May). Experiences and coping strategies of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic (Working Paper No. 28803). National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w28803

- Marinoni, G., Van’t Land, H., & Jensen, T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on higher education around the world. IAU global survey report, 23. Paris, France: International Association of Universities.

- Messacar, D., Handler, T., & Frenette, M. (2021). Predicted earnings losses from graduating during COVID-19. Canadian Public Policy, COVID-19, 47(2), 301–315. doi:10.3138/cpp.2020-109

- Michel, A., Ryan, N., Mattheus, D., Knopf, A., Abuelezam, N., Stamp, K., … Fontenot, H. (2021, May). Undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions on nursing education during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: A national sample. Nursing Outlook, 69, 903–912. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2021.05.004

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center [NSCRC]. (2022). Overview: Fall 2021 enrollment estimates (Tech. Rep.). Herndon, Virginia.

- Orlov, G., McKee, D., Berry, J., Boyle, A., DiCiccio, T., Ransom, T., … Stoye, J. (2021). Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: It is not who you teach, but how you teach. Economics Letters, 202, 109812. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2021.109812

- Pasion, R., Dias-Oliveira, E., Camacho, A., Morais, C., & Franco, R. C. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on undergraduate business students: A longitudinal study on academic motivation, engagement and attachment to university. Accounting Research Journal, 34(2), 246–257. doi:10.1108/ARJ-09-2020-0286

- Rana, S., Anand, A., Prashar, S., & Haque, M. M. (2022). A perspective on the positioning of Indian business schools post COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 17(2), 353–367. doi:10.1108/IJOEM-04-2020-0415

- Ritter, T., & Pedersen, C. L. (2020). Analyzing the impact of the coronavirus crisis on business models. Industrial Marketing Management, 88, 214–224. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.014

- Rodr´ıguez-Planas, N. (2022). Hitting where it hurts most: COVID-19 and low-income urban college students. Economics of Education Review, 87, 102233. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272775722000103

- Ryazanova, O., Wright, A., & Laasch, O. (2021). From the editors—Studying the ongoing change at the individual level: Who am i (becoming) as a management educator and researcher?. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management.

- Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2020). Why business schools need radical innovations: Drivers and development trajectories. Journal of Marketing Education, 42(2), 93–107. doi:10.1177/0273475320922285

- United Nations. (2020). Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. Policy Brief - United Nations, 8–20, 1–25.

Appendix A

Table A1. Parallel trends—placebo test.

Table A2. Difference-in-difference: robustness multiple hypothesis