Abstract

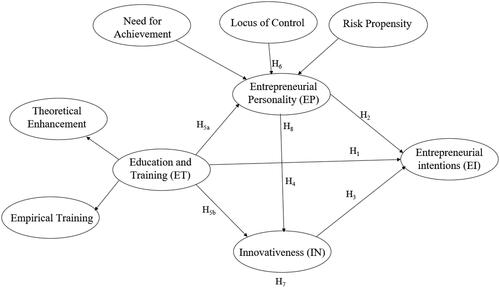

The study investigates the relationship between educational factors (theoretical and empirical training), entrepreneurial personality (need for achievement, locus of control, risk propensity), innovativeness, and the entrepreneurial intentions from 399 students studying in tourism major from universities in Vietnam. The data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation model. The study results suggest that, although educational factors do not directly affect the students’ entrepreneurial intentions, they have an indirect effect mediated via innovativeness. Educational factors also directly impact students’ entrepreneurial personalities and innovativeness, which further impacts their entrepreneurial intentions.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship has been considered a pivotal contributor to sustained economic growth and development in creating employment, innovation, and new product development in developed and developing countries (Kelley et al., Citation2012). In recent years, entrepreneurship has grown worldwide, particularly in Asia and Pacific regions (Heller, Citation2020). In ASEAN countries, the youths strongly prefer entrepreneurship, wherein 31.4% of them work for a startup or are already entrepreneurs (Nguyen, Citation2019). Vietnam, one of the countries in Southeast Asia, saw high tourism growth and has recorded the highest number of tourists in recent years (WTO, Citation2020). Vietnam was ranked 26th position in international tourist arrivals (15.5 million) and 35th in tourism revenue (US$10.9 billion) in 2018 (WTO, Citation2020). Tourism also has become a key economic sector of Vietnam, where the tourism sector contributed 9.2% of the GDP in 2019 (Vietnam Administration in Tourism [VNAT], Citation2020). To strengthen entrepreneurship across the country, in 2016, the Vietnamese government launched the project “Supporting National Innovative Startup Ecosystem to 2025,” named project 844 until 2025, focusing on supporting innovative startup activities such as incubation, business promotion, and investments. The project aims to support around 2,000 startup projects incubated, around 600 startups created, and 100 startups financed by venture investors (Vanbanphapluat, Citation2016) by 2025.

Other than government support, the factors that impact entrepreneurial ambitions are individual, social, cultural, and environmental factors in Vietnam (Nguyen et al., Citation2019). Particularly in the tourism sector, entrepreneurs face numerous challenges from external determinants such as limitations in product types, lack of proper and consistent investment, and lack of strategic promotion, which are not limited to government support and policies (Nguyen, Citation2019). Dis-proportionality regarding entrepreneurship education in the country also contributes to tourism entrepreneurs’ challenges, as institutional solutions for entrepreneurship are limited to particular fields (Hoang et al., Citation2020).

In Vietnam, it is recommended that higher education institutions enhance the tourism curriculum at an undergraduate level to promote entrepreneurship education since it was proven to increase tourism students’ intentions for entrepreneurship significantly (Phuc et al., Citation2020). Albeit many studies have addressed the gap in entrepreneurship studies in Vietnam (Hoang et al., Citation2020; Tung et al., Citation2020: Duong, Citation2022), a dedicated viewpoint and understanding of the tourism sector are phenomenally limited. As numerous services related to the tourism industry in the county, such as lodging, travel, transportation, food and beverages, are closely connected to entrepreneurship and contribute to Vietnam’s national economy, as well as the development of different attract fields (Phuc et al., Citation2020), tourism entrepreneurship is significantly in need of research. A significant body of literature in Vietnam and worldwide focuses on investigating the factors that influence undergraduate students’ entrepreneurial intentions (EI) studying business degrees or mixed degrees (Maheshwari & Kha, Citation2022; Tsai et al., Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of research focusing on the EI of students studying in the tourism major. In response to this call for research, this paper aims to explore this under-researched area in the higher education context and how it elaborates on the entrepreneurship landscape, particularly for students studying tourism in Vietnam. This study will subsequently contribute to practical implications from government policies, educational institutes, and relevant organizations to address appropriate solutions.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Entrepreneurial intentions

The definition of entrepreneurship or entrepreneur is still a point of disagreement among academics. According to Landström (Citation2005), entrepreneurs are innovators who combine resources in novel ways to create new products and bring them to the market. As per Gartner and Carter (Citation2003), entrepreneurship is defined as developing and establishing a new business. Entrepreneurial intentions (EI) are described as a conscious state of mind that leads one’s attention, experience, and conduct toward intended entrepreneurial behavior (Bird, Citation1988). As per Lee and Wong (Citation2004), the entrepreneurial intention is the primary precursor of entrepreneurship. It is the anticipated outcome of planned behaviors and historically has been used to describe a self–prediction to engage in action (Ajzen, Citation1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1977).

Education and training (ET)

Entrepreneurial education is mentioned as one of the aspects that enhances students’ desire to become entrepreneurs. According to Gorman et al. (Citation1997), the content of an entrepreneurial course and following practical entrepreneurial activities significantly impact a student’s desire to pursue entrepreneurship. Phuc et al. (Citation2020) stated that entrepreneurship education had been regarded as an essential component of being an entrepreneur. Hynes’s (Citation1996) research pointed out not considering the formal or informal methods as stand-alone toward developing EI. However, the study emphasized the importance of integrating education (the formal methods) and training (the practical methods) to impact EI collectively (Hynes, Citation1996). Hence, this research is built on the premise that entrepreneurial education should integrate formal education (theoretical enhancement) and practical training to develop students’ skills.

Theoretical enhancement (TH)

Theoretical enhancement is considered a traditional education that focuses on teachers’ direction and related knowledge transmission to students (Eraut, Citation2000). In traditional education, the quantity of teaching influences students’ knowledge accumulation. The theoretical approach to creating and running a business is the main focus of entrepreneurship education, which is related to the conventional teaching style that emphasizes theory as a way of education to assist students in comprehending the outcomes of practice and actions (Nowiński et al., Citation2019).

Empirical training (ET)

Empirical or practical training places a greater emphasis on skill development. In contrast to theoretical knowledge, practical knowledge is firmly linked to a specific environment and is task-based, reflecting an authentic learning environment (Lave, Citation1996). This is related to the activity-based education style, in which practice and actions are utilized to impart knowledge, motivate and ignite passion in the behaviors of aspiring entrepreneurs, recognize opportunities, and manage risk in an entrepreneurial environment (Harmeling & Sarasvathy, Citation2013).

Many academics believe that to improve learning and innovative potential, entrepreneurial education should include an experimental learning perspective as well as some form of interactive pedagogy (Collins et al., Citation2006; Honig, Citation2004; Johannisson et al., Citation1998; Vinten & Alcock, Citation2004; Yballe & O’Connor, Citation2000). Numerous studies have been conducted to examine the effects of entrepreneurship education on students at all levels of learning, starting in primary school (Huber et al., Citation2014; Sánchez, Citation2013; Stadler & Smith, Citation2017) and especially at the university level, which has a significant impact on an individual’s career (Nowiński et al., Citation2019; Walter & Block, Citation2016). As per Donckels (Citation1991), education is crucial in fostering entrepreneurial ambitions because it provides students with the necessary skills and knowledge to motivate them to start new businesses. In support of this view, Saadat et al. (Citation2022) concluded that entrepreneurship education has a favorable and significant impact on entrepreneurial alertness and mindset. As a result, students who participate in entrepreneurship education exhibit more assertive entrepreneurial intentions (Wu & Wu, Citation2008). Practically oriented courses can help emphasize how existing ideas can be developed and strategies can be used to become an entrepreneur, while theoretically oriented courses explain entrepreneurial success (Piperopoulos & Dimov, Citation2015). Based on the above discussion, entrepreneurial education is most effective when TH and ET are integrated and is defined as the new variable, education and training (ET), in this study. Hence, the following hypothesis has been set up based on the above discussion:

H1: Education and training have a positive influence on entrepreneurial intentions.

Entrepreneurial personality (EP)

In 1980, the Big-five model covered a distinct set of entrepreneur characteristics (Digman, Citation1990; Goldberg, Citation1990; Rauch, Citation2014). It consists of five components: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. However, soon after, several studies revealed that the Big-five framework is general and makes it challenging to predict situation-specific entrepreneurial behaviors. Hence, after that the researchers have shifted toward creating a multidimensional personality framework that incorporates other qualities like locus of control, need for achievement (NA), and risk-taking capacity to overcome the limitations of the Big-5 framework.

Need for achievement

In Citation1938, Murray first introduced the “acquired-needs theory,” and need for achievement is one of the dominant needs affecting individual actions toward entrepreneurship. Later, this theory was developed and popularized by McClelland (Citation1985) with the “big three” human motives: need for achievement (NA), need for power (nPow) and need for affiliation (nAff). Out of the three, the nAch is the most important and refers to an individual’s desire for significant accomplishment, mastering skills, and attaining challenging goals (McClelland, Citation1985). Specifically, a person with a higher need for achievement values personal accountability, wants to solve problems independently and enjoys taking reasonable risks (McClelland, Citation1961). As per Lee’s study (Citation1996), a greater need for achievement is a significant factor in how an individual will handle difficult situations and pursue excellence. This view is further supported by Nathawat et al. (Citation1997), who stated that a lower need for achievement is related to low performance, low expectations, and an increased likelihood of failure.

Locus of control (LoC)

Locus of control is a person’s awareness of the consequences of their actions, whether they are under external or internal control. An internal locus of control refers to a person’s belief in their own decisions that control their lives. In contrast, an external locus of control is a person’s belief that the controlling forces are chance, fate, or environmental factors they cannot influence. To be more specific, Sesen’s research (Citation2013) and Mohamed et al. (Citation2023) have reported that students with an internal locus of control tend to have stronger entrepreneurial intentions than students with an external locus of control. Many studies have found that entrepreneurs possess an internal locus of control directly related to decision-making in the professional field (Caliendo et al., Citation2009; Gartner, Citation1985; Perry, Citation1990; Shaver & Scott, Citation1992).

Risk propensity (RP)

Risk propensity refers to the willingness and ability to tolerate the risk (Maheshwari, Citation2021). Risk-taking is one of the most important key traits and is considered “the hallmark of an entrepreneur” (Begley & Boyd, Citation1987). Risk-taking propensity is a key attribute associated with entrepreneurs, as it is understood that entrepreneurs must be able to take risks. Entrepreneurs are more prone to take risks, as per the results of various studies (Cromie, Citation2000; Teoh & Foo, Citation1997). As each aspect of entrepreneurial personality (NA, LoC, and RP) all have a positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions (Gurel et al., Citation2010). Hence, based on the above discussion, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Entrepreneurial personality (NA, LoC, RP) positively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

Innovativeness (IN)

Entrepreneurship and innovation go hand in hand and complement each other. As per Koh (Citation1996), innovativeness is one of the key entrepreneurial preconditions. According to Chen (Citation2007), entrepreneurial leaders think creatively and generate fresh and beneficial ideas. Meanwhile, Lumpkin and Dess (Citation1996) suggested that innovative thinking is about establishing a new company, reorganizing an existing one to boost efficiency, carving out a new product, and exploring new market venues. Ozaralli and Rivenburgh (Citation2016) noted that innovation is a crucial prerequisite for entrepreneurship. Gozukara and Colakoglu (Citation2016) conducted a study with 226 undergraduate students from Istanbul and Turkey to investigate the association between inventiveness and entrepreneurial goals and found a positive relationship between innovation and the EI of students. Likewise, Koh (Citation1996), Mohamed et al. (Citation2023), Syed et al. (Citation2020), and Brandt and Wanasika (Citation2021) also reported a positive correlation between innovativeness and entrepreneurial intention. Based on this discussion, we postulate the below hypothesis:

H3: Innovativeness (creative thinking) positively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

Entrepreneurial personality (EP) and innovativeness (IN)

Marcati et al. (Citation2008) and Kickul and Gundry (Citation2002) show that a proactive personality combined with strategic orientation allows for the identification of a new product or market development potential, which further affects the EI of students. This view is further reinforced by the results of Leonelli et al. (Citation2022). The studies demonstrate that entrepreneurial traits, particularly locus of control, significantly impact startups’ innovativeness, further enhancing an individual’s EI. Various studies proved the impact of personality traits on innovativeness, including LoC (Dawwas & Al-Haddad, Citation2018) and RP (Joshi et al., Citation2015). From the discussion above, the below hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Entrepreneurial personality positively influences innovativeness (creative thinking).

Ertuna and Gurel’s (Citation2011) study in Turkey found that students’ risk-taking tendency interacts with educational factors. This finding was in line with the prior studies conducted by Wu and Wu (Citation2008), Gupta et al. (Citation2004), Chen (Citation2007), and Renko et al. (Citation2015). As per Zhao et al. (Citation2005), entrepreneurs need certain levels of education and training linked with innovativeness to transform customers’ needs into new products and services. On the other hand, some experts believe that formal/traditional education, which focuses primarily on theoretical and conceptual contents, might decrease curiosity, vision, and risk aversion (Shapero, Citation1982). Hence, it is essential to integrate theoretical and practical training to educate the students. According to Ndofirepi (Citation2020), personality traits comprising nAch, LoC, and RP are proven to be significantly enhanced by the effect of education. Educational and training also played a significant role in increasing students’ innovativeness (Perez et al., Citation2022). Based on the above arguments, the below two hypotheses are postulated for this study:

H5a: Education and training have a positive influence on developing entrepreneurial personality.

H5b: Education and training positively influence innovativeness (creative thinking).

Mediating effects of various factors on EI

The studies by Krueger (Citation1993), Krueger et al. (Citation2000), and Karimi et al. (Citation2017) found that personality traits and entrepreneurial abilities influence the desire to pursue entrepreneurship as a career. Acar and Tuncdogan (Citation2019) supported the relationship between education (theoretical and practical) and innovativeness (IN). Based on the findings from various studies, as discussed above, indicate that ET, EP, and IN work as mediators to influence the EI of students. Especially for tourism and hospitality students to gain ideas for new venture formation, education with strong theoretical support in higher education helps to accumulate more creativity through empirical training education, therefore strengthening the intention to become an entrepreneur of students (Zhang et al., Citation2020). In the study by Che Embi et al. (Citation2019), innovativeness was found to mediate entrepreneurship traits of Malaysian students, including nAch, LoC, and RP. As university education was also proven to increase students’ nAch, LoC, RP and lead to a positive enhancement of EI (Ndofirepi, Citation2020; Remeikiene et al., Citation2013), the role of entrepreneurship personality and innovativeness as the mediator at the same time strengthens the relationship between education and training and EI. Hence, based on the above literature, the below three hypotheses are formulated for this study:

H6: Entrepreneurial personality acts as a mediator between education and training and entrepreneurial intentions.

H7: Innovativeness (creative thinking) acts as a mediator between education and training and entrepreneurial intentions.

H8: Entrepreneurial personality and innovativeness (creative thinking) mediate between education and training and entrepreneurial intentions.

The proposed conceptual framework of this study is presented in .

Methodology

Data collection and sampling

This study was conducted in Vietnam using an online survey from July 2021 until October 2021, and the participants included university students enrolled as undergraduate or postgraduate students studying in tourism major. The online survey link was posted on researchers’ professional and personal social media sites, and hence sample selection was random. To identify an appropriate sample size, we followed Hair et al. (Citation2010)’s rule, where the sample size required is at least equal to five times the number of observed variables in the model of the study. Our model had 41 observed variables in the study (which were later reduced to 36 as a part of factor reductions where the factor loadings were less than 0.4), and hence the minimum sample size required for our study was (41*5) = 205. Our study had the initial responses from 449 students, but the data were screened, and the students who were not studying in tourism major were deleted from this study. Hence, the final data for this study included 399 responses, more than the required sample size of 205 participants.

Instrument development (dependent and independent variables)

The study had three independent variables, including Education and Training (ET), entrepreneurial personality (EP), and innovativeness (IN) and one dependent variable, entrepreneurial intentions (EI). The variable theoretical enhancement (TH) consisted of a 4-item scale and empirical training (ET) of a 6-item scale. Three dimensions measured entrepreneurial personality; Need for achievement (NA) (6 items), Locus of Control (LoC) (7 items), and Risk propensity (RP) (6 items). The last independent variable: innovativeness (IN), consisted of a 6-item scale adapted, whereas the dependent variable, entrepreneurial intentions (EI), had a 6-item scale, and all the variables were measured on a scale of 1–7 (1 = extremely disagree and 7 = extremely agree). From the final analysis, one item for NA, two items from LoC, one from RP and one from IN were deleted either due to cross-loadings or the low factor loadings below 0.4. The items used for this study can be seen in .

Table 1. Measurement model with mean, standard deviation, factor loading, reliability, convergent validity and divergent validity.

Data analysis

To analyze the data for this study, SPSS version 26 and AMOS version 26 were used. SPSS was employed to analyze the demographics of the respondents, descriptive statistics, reliability analysis, correlation analysis, check common method bias, and conduct exploratory factor analysis. AMOS was used to evaluate the measurement model’s goodness of fit, and after that, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to verify the reliability and validity of the measurement items. Further, a structural equation model was used to check the designed hypotheses of the study. Finally, the Sobel test was used to test hypotheses with mediation and serial mediation effects in the study (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986).

Results and analysis

Descriptive statistics

shows the mean and standard deviation of all the measurement items, and displays the descriptive measures of the participants.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of participants.

The average age of the study participants was around 21 years, and 76% were female. Most were undergraduate students (92%) studying in public universities (94%). Only 20% of the participants reported starting a business, and 75% mentioned having work experience. Approximately more than one-third (37%) of the participants had a family owning the business.

Common method variance

Common method variance (CMV) is one of the measurement errors in self-reported surveys, which might reduce the reliability and validity of model constructs (Fuller et al., Citation2016). To minimize this effect, we used two approaches: procedural and statistical methods. The study used the procedural method to guarantee that the survey questions were designed clearly. The respondents were also informed about the confidentiality of their responses to get an honest response. Further, the statistical method used for testing CMV was using Harman’s single-factor test. There was no threat of common method bias due to a single factor accounting for 41.3%, which is lower than 50% of the total variance explained (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012).

Measurement model validation

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted first to test the reliability and validity of the model (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The internal validity was checked using Cronbach’s alpha (CA) (α), which ranged from .836 to .947 () and was higher than the acceptable value of 0.7. Composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated further for all the constructs of the study (). The second-order model was adopted for this study as ET and TH had a high correlation (as seen in ), and they fitted well in one construct, and that single construct was named Education and Training (ET). Further, LoC and RP had a high correlation, and hence the common construct entrepreneurial personality (EP) was considered, which comprised NA, RA, and LoC (). The analysis revealed that the model was a good fit with χ2/df = 2.701; CFI = .916; RMSEA = .065 (Hair et al., Citation2010). This final second-order model was also tested for internal reliability using CA (), and all the values were found to be higher than 0.7.

Table 3. Correlations of the constructs.

Table 4. Second-order measurement model with mean, standard deviation, factor loading, reliability, convergent validity and divergent validity.

Further, CR and AVE were tested for this final model, and CR and AVE were higher for all the constructs than the acceptable threshold of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively (Maheshwari, Citation2022) (). In order to check the discriminant validity further, the square root of AVE values was calculated, and the values exceeded the respective correlations of second-order model constructs horizontally and vertically (see ). To test the multicollinearity between the model and second-order variables, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was used. All the VIF values were less than 5, indicating no multicollinearity between the constructs ().

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

The study’s hypotheses were tested using a structural equation model using AMOS. The structural model fit was good per the accepted threshold for SEM, as seen in .

Table 5. Model fit indices.

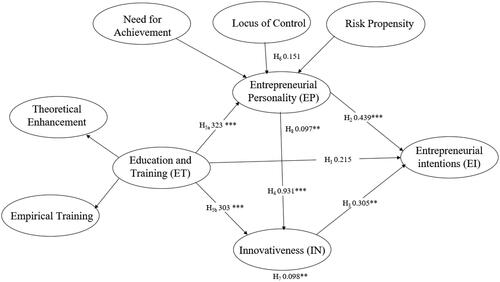

The results from SEM as shown in :

The path coefficient results are displayed in , and the hypotheses results of the study are discussed further.

Table 6. Structural equation model—path analysis results.

The first and fifth hypothesis of the study was to examine how education and training can affect students’ EI, personality, and innovativeness. The results from the first hypothesis suggest that education and training have no direct effect on the EI of students (H1). However, as per the fifth hypothesis, education and training have a positive and significant effect on the personality (β = 0.323) and innovativeness of the students (β = 0.303), with this effect slightly higher on personality. Next, the third hypothesis of the study was to find the influence of innovativeness on the EI of students. The results revealed a significant positive relationship (β = 0.305), suggesting that the more innovative students are more likely to have higher intentions to become entrepreneurs.

This study further examined the effect of entrepreneurship personality (NA, LoC, and RP) on IN and EI of students. This was tested by hypotheses 2 and 4 (H2 and H4) and is supported in this study. The effect of personality on EI (β = 0.439) and IN (β = 0.931) are positively related to the entrepreneurial personality of an individual, with a higher effect of personality found on the innovation of the students. The sixth and seventh hypothesis of the study was to test the mediating effect of education and training on the EI of students mediated via entrepreneurial personality and innovativeness. Even though education and training have no direct effect on the EI of students (as seen by the result of hypothesis 5), it does have an indirect effect of innovativeness (β = 0.098) on students’ EI (as supported by the result from H7). Additionally, there is no mediating effect on the entrepreneurial personality from education and training on EI (H6), but it does have an effect if it is further mediated through innovativeness (H8) (β = 0.097).

Based on hypotheses 5, 6, 7 and 8, despite the non-significant effect of education and training on the EI of students, innovativeness indirectly impacted the EI of students. This result indicates that although education and training might not directly affect students’ EI, it does help develop students’ creativity, which can further impact EI.

Discussion

The study examined the effect of education and training, entrepreneurial personality, and innovativeness (creative thinking) on the entrepreneurial intentions of students studying in tourism major. First, this study suggested that education and training have no direct effect on the EI of students, and there are mixed findings from the literature on the effect of education on the EI of students. Education was found to have no effect on the EI of students in this study, which is consistent as per the research done by Olarewaju et al. (Citation2022). However, various studies, such as those by Schwarz et al. (Citation2009) and Franke and Lüthje (Citation2004), found a significant effect of education on the EI of students, and these study results are inconsistent with these studies from the literature. There is an ongoing debate about educational factors as some scholars such as Airey and Tribe (Citation2000) and Kirby (Citation2004) argued that entrepreneurship education has to be changed to encourage entrepreneurship, while Holmgren and From (Citation2005) mention that entrepreneurship cannot be taught at all. The reason for educational factors not directly affecting entrepreneurship in Vietnam may be that the entrepreneurial courses taught in Vietnam currently focus more on theoretical aspects than practical activities. This might be one reason the students need help to develop the required entrepreneurial skills (Maheshwari, Citation2021). Nevertheless, currently, Vietnamese universities have integrated practical activities into their programs, especially they implemented startup projects for students at the request of the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) as per Decision 1230/QD-BGDDT. However, most of the projects done were in the manufacturing or production field (MOET, Citation2023), and Covid-19 have caused obstacles to businesses and student recruitment in the tourism and hospitality industry (Government news, Citation2022). These issues, to some extent, affect tourism learning and teaching journey, including students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Particularly for entrepreneurship education in higher education, the entrepreneurial intentions of students were found to be increasing longitudinally as their attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control increased (Otache et al., Citation2021). A similar longitudinal effect was also found, particularly among tourism students (Sahinidis et al., Citation2019), thus impacting the sector’s entrepreneurial landscape. As this is a cross-sectional study, this might be another reason for education not impacting students’ EI.

Further, in this study, education and training directly affected tourism students’ innovativeness and entrepreneurial personality. These findings align with the study done by Ertuna and Gurel (Citation2011), who suggested that education interacts with students’ risk-taking capacity. The studies conducted by Wu and Wu (Citation2008) and Renko et al. (Citation2015) found that education has a major impact on innovativeness, consistent with this study’s result.

Next, the study results supported that innovativeness and entrepreneurial personality directly affect the EI of students, which is well in line with previous studies carried out by Gurel et al. (Citation2010). Further, this study found that education and training do not directly affect students’ entrepreneurial intentions. However, innovativeness has fully mediated the relationship between education and training and the EI of students. Many scholars argued that higher entrepreneurial education should include an experimental learning perspective and some form of interactive pedagogy to improve learning and innovative potential (Collins et al., Citation2006; Honig, Citation2004). Similar thoughts have also been supported by a previous study by Acar and Tuncdogan (Citation2019), who supported the relationship between education (from both theoretical and practical standpoints) and innovativeness, which affects the EI of students further.

Conclusion and implications

Entrepreneurial intentions are intuitive, and tourism and hospitality are important industries in Vietnam. Hence, studying the entrepreneurial intentions of students studying tourism is vital as they are the future of this growing industry. Many factors impact entrepreneurial intentions in general, but it is crucial to link educational factors with an individual’s personality traits and innovativeness to unlock their potential to become an entrepreneur fully. Therefore, it is vital to take a holistic approach to understand the students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Hence, this study investigated the role of educational courses designed with the theoretical background and practical training components to present a cohesive and complete education to understand how this can impact the students’ entrepreneurial intentions. The study results suggested that educational courses do not affect the students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Hence, it shows that university education plays a minor role in the students’ entrepreneurial mindset. As personality traits and innovativeness have been found to affect the entrepreneurial intentions of the students significantly, it is suggested that the current education practices must be changed to develop entrepreneurial spirits to foster entrepreneurial mindsets in an individual.

Theoretical implications

Various studies in the literature examine the factors influencing the students’ entrepreneurial intentions with different business degrees. However, research on entrepreneurship in tourism education is scant, especially in Vietnam. This area is evolving; hence, this study contributes to this less explored part of the literature in one of the emerging Asian countries, Vietnam. The study results will be helpful to develop future entrepreneurs in Vietnam in the tourism sector, which can boost the economy since tourism is one of the significant sectors in Vietnam.

In contrast, most previous studies considered these factors in isolation or combined with the theory of planned behavior (TPB) components in Vietnam. The practical training in educational courses and theoretical teaching for the courses can have a massive impact on the students’ entrepreneurial intentions as that helps students experience the real-world applications of the theoretical concepts studied in their courses and develop the necessary entrepreneurship qualities in the students. Although this study did not find the direct effect of education and training on the EI of students, it shows a direct effect on developing students’ personalities and innovativeness, which further influences the EI of students.

Practical implications

This study has some practical implications for educational institutions, relevant organizations, and policymakers. As per the study results, although education and training do not directly affect the students’ intentions, it does have an indirect effect mediated via innovativeness, and further innovativeness has a direct effect on the EI of students, and hence educational factors play a significant role affecting the entrepreneurial intentions of students. Thus, enhancing educational programs by providing more opportunities for students to develop their creativity is crucial. This could be done by designing more practical training for the students and exposing them to practical aspects of the course. Positively, Vietnamese universities, including those offer tourism majors, have tried to strengthen the connection between theory and practice in multiple ways, e.g., through compulsory internships at companies, inviting guest speakers or guest lecturers from industry to universities, organizing occupational competitions, involving students in industry events, and implementing field trips or experience study tours. Tourism is a unique industry because of its ever-changing nature; hence, providing real-time training scope can be an effective solution to help students avoid unnecessarily making mistakes. Education and training have also been found to affect the personality of the students (locus of control and risk-taking capacity). Therefore, educational programs can develop simulation projects to enhance their skills and personality. Thus, this study has practical implications for educational institutions that consider revising the curriculum to develop the entrepreneurship spirits of the students that will enable tourism students to explore their innovativeness and risk-taking skills. This can be possible by embedding the practical component in the courses where the students learn by doing and experience real-world applications. Conversely, the teachers and lecturers at tourism educational institutes who directly impact students’ learning outcomes can update their knowledge with practical experience, e.g., through conducting research with tourism companies or being credited by authorized organizations with a standardized frame of competencies for teaching entrepreneurship in this industry.

At the government level, to nurture entrepreneurship education, the government has been transforming learning and teaching by aspiring educational institutions and issuing policies to instill an entrepreneurial mindset throughout Vietnam’s higher education system. In addition, more startup projects could be customized for tourism students to form a stable entrepreneurship ecosystem. Accordingly, relevant organizations and associations, e.g., the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industries or the Pacific Asia Travel Association, can support students’ entrepreneurship in Vietnam. Early career orientation, starting even at the primary level and growing toward a global business context, is necessary to create a wave in the young generations’ entrepreneurial mindset. A triangle career orientation model involving primary/secondary/high school students—universities—and enterprises/organizations can be enforced more strongly in the Vietnamese educational community to boost the entrepreneurial potential of students and provide on-time coaching to students along their startup journey. Vietnam’s unemployment rate (% of the total labor force) has increased from 1.1% to 2.3% from 2010 to 2020 (World bank data, Citation2021). Therefore, developing entrepreneurial skills in the young generation will help reduce graduates’ dependency on employment and help the country’s economic growth.

Limitations and future research

Some limitations of this study offer avenues for future research. First, the results of this study can be robust if it can be expanded in future. Currently, it is a cross-sectional study, and in the future, a longitudinal study can be conducted to better support the current study’s findings. Second, the study is limited to the students in Vietnam and with regards to generalization, this can be further extended to other Asian regions to increase inclusivity and generalization. Third, gender can be considered as an independent or moderator variable to determine if there are any differences in EI between male and female students. Fourth, the future study can focus on mixed methodology by interviewing the students to get a deeper analysis of what hinders or stimulates an individual to become an entrepreneur. Finally, besides the factors considered in this study, the cultural background and family factors can also be considered to see the impact on the EI of students, as verified in various studies (Gurel et al., 2010; Sesen, Citation2013).

References

- Acar, O. A., & Tuncdogan, A. (2019). Using the inquiry-based learning approach to enhance student innovativeness: A conceptual model. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(7), 895–909. doi:10.1080/13562517.2018.1516636

- Airey, D., & Tribe, J. (2000). Education for hospitality. In Search of hospitality: Theoretical perspectives and debates (pp. 276–291).

- Ajzen, L. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude–behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Begley, T. M., & Boyd, D. (1987). Psychological characteristics associated with performance in entrepreneurial firms and smaller businesses. Journal of Business Venturing, 2(1), 79–93. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(87)90020-6

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. The Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453. doi:10.2307/258091

- Brandt, T., & Wanasika, I. (2021). Innovativeness and entrepreneurial intentions: Students from Finland, Lithuania and USA in comparison. In F. Matos, M. de Fátima, À. Rosa, & I. Salavisa (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th European conference on innovation and entrepreneurship. ECIE 2021 (pp. 137–145). Reading.

- Caliendo, M., Fossen, F. M., & Kritikos, A. S. (2009). Risk attitudes of nascent entrepreneurs–new evidence from an experimentally validated survey. Small Business Economics, 32(2), 153–167. doi:10.1007/s11187-007-9078-6

- Che Embi, N. A., Jaiyeoba, H. B., & Yussof, S. A. (2019). The effects of students’ entrepreneurial characteristics on their propensity to become entrepreneurs in Malaysia. Education + Training, 61(7/8), 1020–1037. doi:10.1108/ET-11-2018-0229

- Chen, M. H. (2007). Entrepreneurial leadership and new ventures: Creativity in entrepreneurial teams. Creativity and Innovation Management, 16(3), 239–249. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2007.00439.x

- Collins, L. A., Smith, A. J., & Hannon, P. D. (2006). Applying a synergistic learning approach in entrepreneurship education. Management Learning, 37(3), 335–354. doi:10.1177/1350507606067171

- Cromie, S. (2000). Assessing entrepreneurial inclinations: Some approaches and empirical evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 9(1), 7–30. doi:10.1080/135943200398030

- Dawwas, A., & Al-Haddad, S. (2018). The impact of locus of control on innovativeness. Int. J. Dev. Sustain, 7(5), 1721–1733.

- Digman, J. M. (1990). Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology, 41(1), 417–440. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002221

- Donckels, R. (1991). Education and entrepreneurship experiences from secondary and university education in Belgium. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 35–42. doi:10.1080/08276331.1991.10600389

- Duong, C. D. (2022). Exploring the link between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of educational fields. Education + Training, 64(7), 869–891. doi:10.1108/ET-05-2021-0173

- ElSaid, O. A., & Fuentes Fuentes, M. del M. (2019). Creative thinking and entrepreneurial attitudes among tourism and hospitality students: The moderating role of the environment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Education, 31(1), 23–33. doi:10.1080/10963758.2018.1480963

- Eraut, M. (2000). Non‐formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(1), 113–136. doi:10.1348/000709900158001

- Ertuna, Z. I., & Gurel, E. (2011). The moderating role of higher education on entrepreneurship. Education + Training, 53(5), 87–402.

- Franke, N., & Lüthje, C. (2004). Entrepreneurial intentions of business students—A benchmarking study. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 01(03), 269–288. doi:10.1142/S0219877004000209

- Forza, C., & Filippini, R. (1998). TQM impact on quality conformance and customer satisfaction: A causal model. International Journal of Production Economics, 55(1), 1–20. doi:10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00007-3

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.008

- Gartner, W. B. (1985). A conceptual framework for describing the phenomenon of new venture creation. The Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 696–706. doi:10.2307/258039

- Gartner, W. B., & Carter, N. M. (2003). Entrepreneurial behavior and firm organising processes. In Handbook of entrepreneurship research (pp. 195–221). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216–1229. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.59.6.1216

- Gorman, G., Hanlon, D., & King, W. (1997). Some research perspectives on entrepreneurship education, enterprise education and education for small business management: A ten-year literature review. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 15(3), 56–77. doi:10.1177/0266242697153004

- Government news (2022). Solving the problem of tourism human resources shortages. Retrieved from https://baochinhphu.vn/giai-bai-toan-thieu-hut-nhan-luc-du-lich-102220426150950135.htm

- Gozukara, I., & Colakoglu, N. (2016). Enhancing entrepreneurial intention and innovativeness of university students: The mediating role of entrepreneurial alertness. International Business Research, 9(2), 34–45. doi:10.5539/ibr.v9n2p34

- Gupta, V., MacMillan, I. C., & Surie, G. (2004). Entrepreneurial leadership: Developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 241–260. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00040-5

- Gurel, E., Altinay, L., & Daniele, R. (2010). Tourism students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 646–669. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2009.12.003

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Harmeling, S. S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2013). When contingency is a resource: Educating entrepreneurs in the Balkans, the Bronx, and beyond. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(4), 713–744. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00489.x

- Heller, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship in the Context of Western vs. East Asian economic models. Seoul Journal of Economics, 33(4), 539–559.

- Hoang, G., Le, T. T. T., Tran, A. K. T., & Du, T. (2020). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning orientation. Education + Training, 63(1), 115–133. doi:10.1108/ET-05-2020-0142

- Holmgren, C., & From, J. (2005). Taylorism of the mind: Entrepreneurship education from a perspective of educational research. European Educational Research Journal, 4(4), 382–390. doi:10.2304/eerj.2005.4.4.4

- Honig, B. (2004). Entrepreneurship education: Toward a model of contingency-based business planning. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3(3), 258–273. doi:10.5465/amle.2004.14242112

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huber, L. R., Sloof, R., & Van Praag, M. (2014). The effect of early entrepreneurship education: Evidence from a field experiment. European Economic Review, 72, 76–97. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.09.002

- Hynes, B. (1996). Entrepreneurship education and training‐introducing entrepreneurship into non‐business disciplines. Journal of European Industrial Training, 20(8), 10–17. doi:10.1108/03090599610128836

- Johannisson, B., Landstrom, H., & Rosenberg, J. (1998). University training for entrepreneurship—an action frame of reference. European Journal of Engineering Education, 23(4), 477–496. doi:10.1080/03043799808923526

- Joshi, M. P., Das, S. R., & Mouri, N. (2015). Antecedents of innovativeness in technology‐based services (TBS): Peering into the black box of entrepreneurial orientation. Decision Sciences, 46(2), 367–402. doi:10.1111/deci.12126

- Karimi, S., Biemans, H. J., Naderi Mahdei, K., Lans, T., Chizari, M., & Mulder, M. (2017). Testing the relationship between personality characteristics, contextual factors and entrepreneurial intentions in a developing country. International Journal of Psychology : Journal international de psychologie, 52(3), 227–240. doi:10.1002/ijop.12209

- Kelley, D. J., Singer, S., & Herrington, M. (2012). The global entrepreneurship monitor. 2011 Global Report, GEM 2011, 7, 2–38.

- Kickul, J., & Gundry, L. (2002). Prospecting for strategic advantage: The proactive entrepreneurial personality and small firm innovation. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(2), 85–97. doi:10.1111/1540-627X.00042

- Kirby, D. A. (2004). Entrepreneurship education: Can business schools meet the challenge? Education + Training, 46, 510–519.

- Koh, H. C. (1996). Testing hypotheses of entrepreneurial characteristics: A study of Hong Kong MBA students. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 11(3), 12–25.

- Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. doi:10.1177/104225879301800101

- Landström, H. (2005). Entreprenörskapets rötter. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lave, J. (1996). Teaching, as learning, in practice. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 3(3), 149–164. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca0303_2

- Lee, J. (1996). The motivation of women entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women in Management Review, 11(2), 18–29. doi:10.1108/09649429610112574

- Lee, S. H., & Wong, P. K. (2004). An exploratory study of technopreneurial intentions: A career anchor perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(1), 7–28. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00112-X

- Leonelli, S., Masciarelli, F., & Fontana, F. (2022). The impact of personality traits and abilities on entrepreneurial orientation in SMEs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 34(3), 269–294. doi:10.1080/08276331.2019.1666339

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y.-W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. The Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172. doi:10.2307/258632

- Maheshwari, G. (2021). Factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions the most for university students in Vietnam: Educational support, personality traits or TPB components? Education + Training, 63(7/8), 1138–1153. doi:10.1108/ET-02-2021-0074

- Maheshwari, G. (2022). Entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam: Integrated model of social learning, human motivation, and TPB. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100714. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100714

- Maheshwari, G., & Kha, K. L. (2022). Investigating the relationship between educational support and entrepreneurial intention in Vietnam: The mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the theory of planned behavior. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100553. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100553

- Marcati, A., Guido, G., & Peluso, A. M. (2008). The role of SME entrepreneurs’ innovativeness and personality in the adoption of innovations. Research Policy, 37(9), 1579–1590. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.06.004

- McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- McClelland, D. C. (1985). Human motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman.

- Meydan, C. H. (2015). Sesen H. Yapisal esitlik modellemesi, Amos uygulamalari [Structural equation modeling, AMOS applications] Ankara: Detay.

- MOET (2023). Students’ start-up journey forum. Retrieved from https://moet.gov.vn/tintuc/Pages/tin-tong-hop.aspx?ItemID=8429

- Mohamed, M. E., Elshaer, I. A., Azazz, A., & Younis, N. S. (2023). Born not made: The impact of six entrepreneurial personality dimensions on entrepreneurial intention: Evidence from healthcare higher education students. Sustainability, 15(3), 2266. doi:10.3390/su15032266

- Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Nathawat, S. S., Singh, R., & Singh, B. (1997). The effect of need for achievement on attributional style. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137(1), 55–62. doi:10.1080/00224549709595413

- Ndofirepi, T. M. (2020). Relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial goal intentions: Psychological traits as mediators. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 1–20. doi:10.1186/s13731-020-0115-x

- Nguyen, Q. N. (2019). A decade-long development of Vietnam tourism: Achievements, limits, and solutions. Journal of Economic Development, 46–51.

- Nguyen, A. T., Do, T. H. H., Vu, T. B. T., Dang, K. A., & Nguyen, H. L. (2019). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intentions among youths in Vietnam. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 186–193. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.039

- Nguyen, D. (2019). VnExpress. 1 in 4 Vietnamese Wants to Be an Entrepreneur. Retrieved from https://e.vnexpress.net/news/business/industries/1-in-4-vietnamese-wants-to-be-an-entrepreneur-3968914.html

- Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Olarewaju, A. D., Gonzalez-Tamayo, L. A., Maheshwari, G., & Ortiz-Riaga, M. C. (2022). Student entrepreneurial intentions in emerging economies: Institutional influences and individual motivations. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. doi:10.1108/JSBED-05-2022-0230

- Otache, I., Umar, K., Audu, Y., & Onalo, U. (2021). The effects of entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal approach. Education + Training, 63(7/8), 967–991. doi:10.1108/ET-01-2019-0005

- Ozaralli, N., & Rivenburgh, N. K. (2016). Entrepreneurial intention: Antecedents to entrepreneurial behavior in the USA and Turkey. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 6(1), 1–32. doi:10.1186/s40497-016-0047-x

- Perez, J. P., Martins, I., Mahauad, M. D., & Sarango-Lalangui, P. O. (2022). A bridge between entrepreneurship education, program inspiration, and entrepreneurial intention: the role of individual entrepreneurial orientation. Evidence from Latin American emerging economies. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies. doi:10.1108/JEEE-04-2021-0137

- Perry, C. (1990). After further sightings of the Heffalump. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 5(2), 22–31. doi:10.1108/02683949010141589

- Phuc, P., Vinh, N., & Do, Q. (2020). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention among tourism undergraduate students in Vietnam. Management Science Letters, 10(15), 3675–3682. doi:10.5267/j.msl.2020.6.026

- Piperopoulos, P., & Dimov, D. (2015). Burst bubbles or build steam? Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self‐efficacy, and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 970–985. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12116

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Quintana, S. M., & Maxwell, S. E. (1999). Implications of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 27(4), 485–527. doi:10.1177/0011000099274002

- Rauch, A. (2014). Predictions of entrepreneurial behavior: A personality approach. In Handbook of research on small business and entrepreneurship. London, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Remeikiene, R., Startiene, G., & Dumciuviene, D. (2013). Explaining entrepreneurial intention of university students: The role of entrepreneurial education. In International conference (Vol. 299, p. 307). Zadar, Croatia.

- Renko, M., El Tarabishy, A., Carsrud, A. L., & Brännback, M. (2015). Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 54–74. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12086

- Saadat, S., Aliakbari, A., Alizadeh Majd, A., & Bell, R. (2022). The effect of entrepreneurship education on graduate students’ entrepreneurial alertness and the mediating role of entrepreneurial mindset. Education + Training, 64(7), 892–909. doi:10.1108/ET-06-2021-0231

- Sahinidis, A. G., Polychronopoulos, G., & Kallivokas, D. (2019). Entrepreneurship education impact on entrepreneurial intention among tourism students: A longitudinal study. In Strategic innovative marketing and tourism: 7th ICSIMAT, Athenian Riviera, Greece, 2018 (pp. 1245–1250). Springer International Publishing.

- Sánchez, J. C. (2013). The impact of an entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurial competencies and intention. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3), 447–465. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12025

- Schwarz, E. J., Wdowiak, M. A., Almer‐Jarz, D. A., & Breitenecker, R. J. (2009). The effects of attitudes and perceived environment conditions on students’ entrepreneurial intent: An Austrian perspective. Education + Training, 51, pp. 272–291.

- Sesen, H. (2013). Personality or environment? A comprehensive study on the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Education + Training, 55(7), 624–640. doi:10.1108/ET-05-2012-0059

- Shapero, A. (1982). Are business schools teaching business? Inc., January, p. 13.

- Shaver, K. G., & Scott, L. R. (1992). Person, process, choice: The psychology of new venture creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2), 23–46. doi:10.1177/104225879201600204

- Stadler, A., & Smith, A. M. (2017). Entrepreneurship in vocational education: A case study of the Brazilian context. Industry and Higher Education, 31(2), 81–89. doi:10.1177/0950422217693963

- Syed, I., Butler, J. C., Smith, R. M., & Cao, X. (2020). From entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial intentions: The role of entrepreneurial passion, innovativeness, and curiosity in driving entrepreneurial intentions. Personality and Individual Differences, 157, 109758. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.109758

- Teoh, H. Y., & Foo, S. L. (1997). Moderating effects of tolerance for ambiguity and risk-taking propensity on the role conflict-perceived performance relationship: Evidence from Singaporean entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(1), 67–81.

- Tsai, K. H., Chang, H. C., & Peng, C. Y. (2016). Extending the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: A moderated mediation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 445–463. doi:10.1007/s11365-014-0351-2

- Tung, D. T., Hung, N. T., Phuong, N. T. C., Loan, N. T. T., & Chong, S. C. (2020). Enterprise development from students: The case of universities in Vietnam and the Philippines. The International Journal of Management Education, 18(1), 100333. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100333

- Vanbanphapluat (2016). Retrieved from https://vanbanphapluat.co/decision-844-qd-ttg-approval-assistance-policies-national-innovative-startup-ecosystem-2025

- Vietnam Administration in Tourism (VNAT) (2020). Vietnam tourism annual report 2019. Retrieved from https://images.vietnamtourism.gov.vn/vn/dmdocuments/2020/E-BCTNDLVN_2019.pdf

- Vinten, G., & Alcock, S. (2004). Entrepreneuring in education. International Journal of Educational Management, 18(3), 188–195. doi:10.1108/09513540410527185

- Vodă, A. I., & Florea, N. (2019). Impact of personality traits and entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of business and engineering students. Sustainability, 11(4), 1192. doi:10.3390/SU11041192

- Walter, S. G., & Block, J. H. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 216–233. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.10.003

- World bank data (2021). Retrieved from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#

- World Tourism Organization (2020). World tourism barometer. Retrieved from https://www.eunwto.org/doi/abs/10.18111/wtobarometereng.2020.18.1.1?journalCode=wtobarometereng

- Wu, S., & Wu, L. (2008). The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in China. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 15(4), 752–774. doi:10.1108/14626000810917843

- Yballe, L., & O’Connor, D. (2000). Appreciative pedagogy: Constructing positive models for learning. Journal of Management Education, 24(4), 474–483. doi:10.1177/105256290002400406

- Zhang, Y., Duysters, G., & Cloodt, M. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10(3), 623–641. doi:10.1007/s11365-012-0246-z

- Zhang, S. N., Li, Y. Q., Liu, C. H., & Ruan, W. Q. (2020). Critical factors identification and prediction of tourism and hospitality students’ entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 26, 100234. doi:10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.100234

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S., & Hills, G. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265