ABSTRACT

Drawing on silencing and online incivility literature, this study examined how people evaluate and respond to impolite and intolerant online opinions in different discussion contexts. Based on a between-subject online survey experiment in the U.S. (N = 959), we found that people perceived impoliteness and intolerance as uncivil, leading to intentions to silence others. The results also revealed that intolerance resulted in higher perceived incivility and silencing intentions compared to impoliteness. Furthermore, the direct effects of impoliteness and intolerance on perceived incivility and their indirect effects on silencing intentions through perceived incivility were stronger in agreeing discussions than in disagreeing ones. However, social endorsement cues did not moderate the mechanisms.

The “incivility crisis” in the online political landscape has recently attracted much scholarly and public attention. Normatively speaking, online public discourse featuring offensiveness and disrespectfulness has been criticized for harming the democratic ideals for free and respectful exchange of ideas among citizens (Papacharissi, Citation2004; Rossini, Citation2022). Empirical research finds that online incivility has detrimental impacts, such as leading to opinion polarization (Anderson et al., Citation2014), eliciting negative evaluations of news outlets and news content (Lück & Nardi, Citation2019), and inhibiting engagement behavior (Lu et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, inconsistent findings of the effects of incivility have been reported (Van’t Riet & Van Stekelenburg, Citation2022), suggesting that incivility effects may vary along different factors. Following this line of research, the present study operationalizes online incivility in terms of its different forms, considering the discussion context in which it occurs and its effects beyond political engagement and news consumption.

Specifically, this study advances the literature in three-fold. First, we differentiate online incivility into impoliteness and intolerance when examining its effects. While both forms of incivility are prevalent on the internet (Rega et al., Citation2023; Rossini, Citation2022), they are distinct from each other. Impoliteness, such as insulting and profane language, represents personal-level norm violations, whereas intolerance toward social groups violates democratic norms (Muddiman, Citation2017; Papacharissi, Citation2004). Given the different levels of toxicity pertinent to impoliteness and intolerance, some point out that, unlike intolerance, impoliteness is not necessarily harmful because it can sometimes prompt people to engage in dynamic and active political discussions with others (G. Chen et al., Citation2019; Rossini, Citation2022).

Second, we highlight the role of discussion contexts in shaping the varying effects of impoliteness and intolerance. Studies in the contextual tradition note that interpersonal and aggregate discussion contexts are key to shaping political communication (Huckfeldt, Citation2007; McClurg, Citation2006). Given the increasing opportunities to encounter diverse perspectives on the internet, political disagreement has been treated as an interpersonal discussion context that reconfigures the dynamics of online political communication (H. T. Chen, Citation2018; Gil de Zuniga et al., Citation2018). For the aggregate discussion context, social endorsement cues in the online environment constitute a useful bandwagon heuristic for people to scan for social approval or disapproval of an opinion (Sundar et al., Citation2015). Recent research shows that both indicators of discussion contexts can condition the effects of online incivility (J. W. Kim & Park, Citation2019; Lu & Liang, Citation2024). Our study furthers the understanding of the varying effects of different types of online incivility through a contextual lens.

Third, we introduce the intention to silence others as a behavioral outcome of online incivility to enrich our understanding of incivility effects. Silencing others, referring to the attempt to suppress public forms of expression (Tsfati & Dvir-Gvirsman, Citation2018), represents a type of informal, expressive political participation. Silencing others can be viewed as a main conduit for opinion formation because it creates the impression that certain opinions are unpopular, the distribution of which should be hindered (Tsfati & Dvir-Gvirsman, Citation2018). Researchers have identified the personality and psychological antecedents of belief in the importance of silencing others (Tsfati, Citation2020). Our findings extend the literature by illustrating how content features in varying discussion contexts would prompt the use of silencing others as a public opinion strategy in online political discussions.

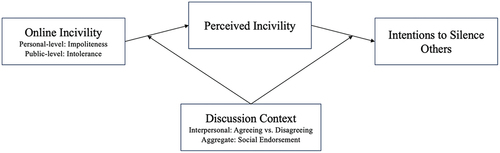

A Conceptual Framework of Silencing Online Incivility

Silencing others is an expressive, unconventional political participation, which denotes the active role that individuals play in suppressing or blocking various public forms of expression of others (Tsfati & Dvir-Gvirsman, Citation2018). From the motivational perspective, silencing others entails one’s (in)acceptance of particular political views and one’s tendency to exert power on others. Broadly speaking, silencing others contributes to the formation of public opinion because it makes some opinions less visible. Silencing others encompasses many forms, ranging from a request to refrain from expressing a view to corrective action that explains that the expressed view is offensive (Tsfati & Dvir-Gvirsman, Citation2018). Silencing others could be either explicit, directed toward the other party, or implicit and achieved through various means.

The online environment provides a unique opportunity to examine silencing behaviors. Given that silencing others online is less intrusive and remains largely unknown to the party being silenced, it is practiced more frequently and even has become routinized. One who aims to undermine other’s opinions could leverage technological affordance on websites, including flagging, downvoting, or hiding certain content (Crawford & Gillespie, Citation2016; Naab et al., Citation2018). While flagging often leads to the deletion of certain content by moderators or platforms (Naab et al., Citation2018), downvoting or hiding content is more deliberate as individuals signal the algorithms that such content is unfavorable with the aim of reducing its visibility (Lu, Citation2020).

Only a few empirical studies have examined the intentions of silencing others in the offline environment and focused primarily on the belief in the importance of silencing others (Tsfati & Dvir-Gvirsman, Citation2018; Tsfati, Citation2020). We extend this line of research by investigating intentions to silence others on the internet and further argue that people may form such intentions due to undesirable content features of the online discourse. Specifically, we focus on online incivility, defined as offensive and disrespectful public discussion on the internet (Anderson et al., Citation2014). Prior research shows that online incivility is undesirable as people tend to avoid (Lu et al., Citation2022; Muddiman & Scacco, Citation2023), flag, and dislike such content (Naab et al., Citation2018; Ziegele et al., Citation2020). However, these studies did not address different types of online incivility. According to Muddiman (Citation2017), online incivility can be distinguished into personal and public levels: the former, also known as impoliteness, encompasses insulting and obscene language that violates personal-level norms; the latter, such as intolerance, refers to communication acts that threaten democratic norms.

It should be noted that incivility is in the eyes of beholders (Herbst, Citation2010). People perceive incivility differently depending on social demographics, discussants, as well as the targets that are being directed in uncivil communication (Kenski et al., Citation2020; Liang & Zhang, Citation2021). More importantly, online incivility across various discussion contexts, as marked by disagreement and social endorsement, causes different levels of psychological reactance (Lu & Liang, Citation2024), indicating that discussion contexts may shape perceived incivility and subsequent behavior. Given that perceived incivility serves as an important mechanism that links exposure to online incivility and its outcomes (Liang & Zhang, Citation2021; Lu et al., Citation2022; Muddiman & Scacco, Citation2023), we propose a conceptual framework to examine the extent to which impoliteness and intolerance across different discussion contexts would prompt one’s intentions to silence others through perceived incivility ().

Impoliteness, Perceived Incivility, and Intentions to Silence Others

Impoliteness is originally understood as violations of politeness norms in face-to-face communication. According to politeness theory (Brown & Levinson, Citation1987), people have a basic want to protect their public self-concepts, also known as “face.” There are two components pertinent to face wants. Positive face refers to the want of one’s actions to be unimpeded by others. Negative face is one’s want to be desirable to at least some others. Impoliteness, such as using insulting and rude expressions, indicates that the speaker has a negative evaluation of some aspect of the hearer’s positive face, thus leading to a threat to the hearer’s positive face (Brown & Levinson, Citation1987). Mutz and Reeves (Citation2005) conceptualize political incivility, such as yelling, name-calling, profanity, and swearing, as a communication practice that violates politeness norms in televised political debates. Scholars categorize political elites’ violation of politeness norms as personal-level incivility (Muddiman, Citation2017) or utterance incivility (Stryker et al., Citation2016).

The interactive and anonymous online environment has given rise to impolite expression in political discussions among the public. According to Papacharissi (Citation2004), impoliteness is an interpersonal speech style that lacks etiquette and formality in online discussion, such as vulgarity, name-calling, and using all-caps. Studies examining user comments on news websites conceptualize online incivility mainly through the impoliteness dimension. For example, Coe et al. (Citation2014, p. 661) define incivility as “using profanity or language that would not be considered proper (e.g., pissed, screw).” Anderson et al. (Citation2014) refer to uncivil comments as those using impolite language. Most recently, Rossini (Citation2022, p. 404) emphasizes that incivility [impoliteness] is “a context-dependent feature of discourse that may convey a rude or disrespectful tone,” and these attributes will not influence the substance of the message. Given that impoliteness may still interrupt smooth interactions in online political discussions (Papacharissi, Citation2004), we treat impoliteness as a sub-dimension of online incivility.

Empirical research show that people perceive impoliteness, such as vulgarity and name-calling, as uncivil (Kenski et al., Citation2020; Muddiman, Citation2017). Also, people tend to silence such political discourses through flagging, reporting, and other types of corrective action (Naab et al., Citation2018; Ziegele et al., Citation2020). These findings suggest that impoliteness on the internet can lead to perceived incivility and intentions to silence others. Psychological research emphasizes that exposure to content features (external salience) does not necessarily mean that people can perceive these features (internal salience) (Schmid, Citation2007). Recent research has corroborated this claim by identifying perceived incivility as a psychological pathway for the behavioral effects of online incivility, independent from other mechanisms (Liang & Zhang, Citation2021; Lu et al., Citation2022; Muddiman & Scacco, Citation2023). Taken together, we propose:

H1:

Impoliteness leads to a higher level of (a) perceived incivility and (b) intentions to silence others than politeness.

H2:

Impoliteness indirectly leads to intentions to silence others via perceived incivility.

Intolerance, Perceived Incivility, and Intentions to Silence Others

Public-level incivility ranges from stereotypes, sexism, racism, and xenophobia to misinformation, deception, and a lack of reciprocity (Bormann et al., Citation2022; Muddiman, Citation2017). Unlike personal-level incivility violating interpersonal norms, public-level incivility often violates democratic norms that guide the political deliberative processes (Muddiman, Citation2017; Papacharissi, Citation2004). Scholars underscore the need to distinguish between personal- and public-level incivility. Papacharissi (Citation2004) notes that impoliteness is a violation of conversational contract, whereas [public-level] incivility is a set of speech acts that deny personal freedoms or stereotype social groups, thus threatening the negative collective face and the democratic goals. Similarly, Stryker et al. (Citation2016) contend that [public-level] incivility goes beyond impoliteness that features “negativity or rudeness or attacks ‘on face’ per se” (p. 548). In studying online user comments, Rossini (Citation2022) uses tone and substance to distinguish personal-level incivility (impoliteness) from public-level incivility (intolerance).

Intolerance expressed on the internet is a type of public incivility that violates democratic norms and individual rights. Intolerance often involves offending, derogating, silencing, or undermining specific groups due to their personal, social, sexual, ethnical, and religious or cultural characteristics (Rossini, Citation2022). Empirical research shows that intolerant discourse is prevalent in online political discussions (Rega et al., Citation2023). This would be detrimental to the functioning of a pluralist democracy. People deem intolerant expressions such as racial slurs, threatening, and encouraging harm to specific groups as very or extremely uncivil (Stryker et al., Citation2016). Gervais (Citation2021) finds that intolerant and racist expression among political candidates leads to disgust among the American public.

This study focuses on intolerance toward women in online political discussions. Sexism is manifested as expressions of disrespect, humiliation, and even hatred toward women. According to the theory of ambivalent sexism, intolerant expression toward women encompasses both hostile and benevolent dimensions (Glick & Fiske, Citation1996). Hostile sexism conveys antipathy toward women through overtly misogynistic and insulting comments on women. Benevolent sexism represents general stereotypes and conventional rules about women under the chivalrous ideology, such as the idea that women and girls need to be protected by men (Blumell et al., Citation2019). It is found that people are likely to silence hateful comments aimed toward women by flagging and directly interrogating the harasser on the Internet (Lu & Luqiu, Citation2023; Wilhelm & Joeckel, Citation2019). These works suggest that intolerance on the internet could lead to perceived incivility and intentions to silence others. Given that perceived incivility could function as a psychological mechanism, we posit:

H3:

Intolerance toward women leads to a higher level of (a) perceived incivility and (b) intentions to silence others than tolerance.

H4:

Intolerance toward women indirectly leads to intentions to silence others via perceived incivility.

The Role of Discussion Context

Discussion context refers to the environments and circumstances in which political discussions occur. It encompasses the topic being discussed, the participants involved, their perspectives, and the architecture of the discussion space. McClurg (Citation2006) theorized that political discussion is a multilayered phenomenon that features both interpersonal and aggregate levels. Interpersonal discussion context usually rests on the compositions, opinions, and other features of one’s core social network. Interpersonal disagreement, a key trait of the interpersonal discussion context, captures the misalignment of one’s attitudes with the discussant on social and political issues and shapes one’s political participation (McClurg, Citation2006). The aggregate discussion context taps into the broader environment beyond one’s network, such as the neighborhood information environment (Huckfeldt, Citation2007). Neighborhood partisan context, for example, signals how popular a political view is and further categorizes people into political majority and minority.

The notions of interpersonal and aggregate discussion contexts are also relevant online. Like what people encounter in face-to-face discussions, they can come across information on the internet that either supports or challenges their political views (Wojcieszak & Mutz, Citation2009). Although the online discussant might not be part of one’s core social network, the agreeable or disagreeable dyad between one and the discussant creates an immediate interpersonal context for political discussion. Meanwhile, we argue that social endorsement cues, such as likes, shares, and votes on the internet, represent the aggregate discussion context because these cues indicate how popular a given opinion is in the eyes of the crowd beyond one’s discussion network. As Bormann et al. (Citation2022) point out, the evaluation of incivility may diverge between contexts. Hence, we incorporate these two types of discussion contexts.

Regarding discussion context at the interpersonal level, there are at least two contrasting expectations about the differential effects that the stance of the discussion may bring about. One expectation is that people might be more lenient toward impoliteness and intolerance in agreeing discussions than those in disagreeing ones. From the perspective of cognitive dissonance theory, humans, by nature, are predisposed to favor information congenial to their prior beliefs (Festinger, Citation1957). Research has found that people evaluate pro-attitudinal humor more favorably than counter-attitudinal ones (Peifer & Holbert, Citation2016). Driven by the tendency of ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation (Tajfel, Citation1978), it is likely that one is motivated to accept and justify a certain level of incivility in agreeing discussions and discount such content in disagreeing ones. Indeed, disagreeing discussions could exacerbate the negative effects of incivility in that people experienced higher levels of anger and aversion when encountering uncivil disagreement than uncivil agreement (Gervais, Citation2015; Hwang et al., Citation2018).

The other expectation is that one might be more sensitized to incivility in agreeing discussions than disagreeing ones. Social identity theory holds that people tend to act to win social acceptance from others and to be perceived favorably by others. In this sense, if an opinion that aligns with one’s own belief is expressed in a notorious way, it may miss the opportunity to present the opinion in a valued direction. This is termed the black sheep effect, referring to one’s inclination to derogate similar others who deviate from group norms and threaten one’s positive self (Marques et al., Citation1988). Following this rationale, one would be more likely to perceive impoliteness and intolerance in agreeing discussions as uncivil and intend to silence them. Empirical research shows that political disagreement could attenuate the effects of incivility on negative cognition and emotion (Lu & Liang, Citation2024). Several other studies find no evidence of an interaction effect between discussion stance and incivility (Lück & Nardi, Citation2019; Masullo et al., Citation2021). Given the inconsistent findings, we ask:

RQ1:

Will the direct effect of impoliteness on (a) perceived incivility and (b) intentions to silence others differ across agreeing and disagreeing discussions? Will (c) the indirect effect of impoliteness on intentions to silence others via perceived incivility differ across agreeing and disagreeing discussions?

RQ2:

Will the direct effect of intolerance toward women on (a) perceived incivility and (b) intentions to silence others differ across agreeing and disagreeing discussions? Will (c) the indirect effect of intolerance on intentions to silence others via perceived incivility differ across agreeing and disagreeing discussions?

For the aggregate discussion context, we anticipate two competing mechanisms at play. In online communication, social endorsement cues may give participants heuristics about the popularity and credibility of certain content. The bandwagon effects perspective suggests that individuals are more likely to adopt items that have received more favorable peer reviews or greater popularity (Sundar et al., Citation2015). In online discussions, the commonly available metrics, such as the number of views, comments, and likes, could serve as bandwagon cues. These metrics might help users evaluate the content’s popularity or acceptance. Individuals may consider prevalent behavior appropriate or acceptable even if the behavior is problematic. Under this framework, Li and Sundar (Citation2022) demonstrated that strong bandwagon cues (most viewers liked this video) could reduce reactance and increase the persuasiveness of health messages. Following this reasoning, social endorsement cues could mitigate the effects of impoliteness and intolerance on perceived incivility and intentions to silence others.

Another expectation is that social endorsement cues may not attenuate the effects of impoliteness and intolerance on perceived incivility and intentions to silence others. One recent meta-analysis shows that the strength of the positive effects of bandwagon cues depends on if the message was related to the topic (Wang et al., Citation2023). Given that both impoliteness and intolerance in online discussions make people hard to find fact-based and reasoned information (Lampe et al., Citation2014), people may judge incivility as off-topic or irrelevant. Indeed, Hilverda et al. (Citation2018) reveal that the effect of comments, a type of social endorsement cue, occurs only when people perceive those comments as useful. If people deem uncivil discourses useless, social endorsement cues may not reduce incivility perceptions and intentions to silence others. Based on the contradictory predictions, we ask:

RQ3:

Will the direct effect of impoliteness on (a) perceived incivility and (b) intentions to silence others differ across social endorsement levels? Will (c) the indirect effect of impoliteness on intentions to silence others via perceived incivility differ across social endorsement levels?

RQ4:

Will the direct effect of intolerance toward women on (a) perceived incivility and (b) intentions to silence others differ across social endorsement levels? Will (c) the indirect effect of intolerance on intentions to silence others via perceived incivility differ across social endorsement levels?

Method

Participants and Procedure

A 2 (polite vs. impolite) × 2 (tolerant vs. intolerant) × 2 (agreeing vs. disagreeing discussion) × 3 (high vs. low vs. no social endorsement) between-subjects online experiment was conducted after the university’s institutional review board approved the study protocol. U.S. participants at least 18 years old were recruited in July 2022 from Prolific, an online survey panel widely used in social and behavioral sciences research. After consenting, participants answered questions about their abortion attitudes and social demographics and were then randomly assigned to one of the 24 experimental conditions. In the posttest, they answered questions about the key variables and manipulation checks. Participants received US$1.00 as compensation. It took an average of 4.8 minutes to finish the experiment. The final sample has 959 valid respondents (Appendix I for participant details).

Stimuli Construction

We chose the issue of abortion for the following reasons. First, abortion is a hotly debated issue in the U.S. Most U.S. citizens tend to have a clear stance toward the issue, and they could be more sensitive to different stances held by others. Also, clear stances toward this topic could avoid losing data and statistical power if too many participants indicated they had neutral stances. Second, uncivil comments are abundant in online discussions surrounding polarized issues, such as abortion. As abortion concerns women’s reproductive rights, many comments represent intolerance toward women. At the time of the study, the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturn of Roe v. Wade added momentum to the debates on abortion, which makes our experiment more realistic and practically meaningful.

We followed a multi-step process to construct the stimuli. One researcher searched and read user comments under news stories on abortion from Reddit.com, a popular social media website in the U.S. The researcher extracted key arguments used in pro-choice or pro-life comments and elements indicating tolerance or intolerance toward women. Based on previous research (G. Chen & Lu, Citation2017; Coe et al., Citation2014), we used profanity, name-calling, and cap letters to operationalize impoliteness. After rigorous pretests, a total of 24 stimuli were constructed (Appendix II and Table S1). We simulated the encounter using the Reddit layout. Reddit has experienced a sharp increase in incivility (Reddit, Citation2021), which enhances the realism of the experiment. Its anonymous nature could reduce potential noises (e.g., identity cues in user profiles) that may taint the effects identified in our study.

Measures

Attitudes toward abortion were measured on a 7-point semantic differential scale (Albarracín & Mitchell, Citation2004), including whether abortion is un/acceptable, whether they favor/oppose abortion rights, and whether abortion is right or wrong (α = .93). The measure was dummy-coded into pro-life and pro-choice groups by mid-point 4. Participants with neutral stances were omitted from subsequent analyses. The agreeing vs. disagreeing discussion conditions were created based on whether the stance of the user comment matched the participant’s stance toward abortion, as indicated in the screening question.

Perceived incivility was measured with the descriptors “uncivil,” “rude,” “unnecessary,” and “disrespectful” on a 7-point scale (Kenski et al., Citation2020; α = .97; M = 5.24, SD = 2.14).

Intentions to silence others were measured on the likelihood of the following behavior on a 7-point scale: “I would downvote this comment,” “I would hide this comment,” and “I would click the report button to flag the comment” (adapting from Crawford & Gillespie, Citation2016; Ziegele et al., Citation2020; α = .78; M = 3.48, SD = 2.07).

Manipulation Check Questions

The study included four manipulation check questions to ensure the participants perceived the comment attributes as manipulated. For impoliteness, participants were asked how much they perceived the comment as “profane,” “vulgar,” and “rude” (α = .94). For intolerance, participants rated how intolerant the comment was toward women using the four-item scale, including “sexist,” “discriminatory of women,” “resentment towards women,” and “intolerant of women” (α = .98). For discussion stance, participants evaluated whether the comment was anti- or pro-abortion on a 7-point semantic differential scale. Lastly, participants recalled the level of social endorsement. All manipulation checks were successful (Appendix III).

Analytical Strategy

We conducted a series of linear regression models in predicting perceived incivility and intentions to silence others separately, using impoliteness, intolerance, disagreeing discussion (agreeing discussion as the baseline), and social endorsement (no endorsement cues as the baseline) as independent variables. For indirect effects, we used the mediation packages in R to estimate the coefficients (Imai et al., Citation2010), which is a modern approach to evaluating the causal roles of mediators. It is more general and robust than conventional mediation analysis based on path analysis or structural equation modeling.

Results

Direct Effects

The results of OLS regression modeling (, Model I) show that impolite content led to a higher level of perceived incivility than polite content (B = 1.18, SE = 0.11, p < .001). Intolerant content resulted in a higher level of perceived incivility than tolerant content (B = 2.22, SE = 0.11, p < .001). Therefore, H1a and H3a are supported. Besides, disagreeing discussion also led to a higher level of perceived incivility than agreeing discussion (B = 1.01, SE = 0.11, p < .001). The endorsement level did not have a direct effect on incivility perceptions.

Table 1. Predicting perceived incivility and silencing intention.

As for the effects on intentions to silence others (H1b and H3b), Model III shows that both intolerance and disagreeing discussion are positively associated with intentions to silence others (B = 1.86, SE = 0.11, p < .01; B = 1.36, SE = 0.11, p < .01); however, impoliteness is not directly related to intentions to silence others (B = 0.12, SE = 0.11, p = .27). Therefore, H1b is not supported while H3b is supported. Model V suggests that perceived incivility is positively associated with intentions to silence others (B = 0.33, SE = 0.03, p < .01), and thus, impoliteness may exert indirect effects on intentions to silence others via perceived incivility.

To compare the effect sizes of politeness and intolerance on perceived incivility, we calculated the unique R2 using the R2 in Model I minus the R2, excluding politeness or intolerance. Our results indicate that the main effect of intolerance on perceived incivility is greater than that of impoliteness, given that intolerance can uniquely account for 27.0% variance. In comparison, impoliteness can uniquely account for 7.6% variance. A formal ANOVA test of the two models is significant (p < .001). Using the same method to test the difference in effects on intentions to silence others, we found that intolerance can uniquely explain 20.1% variance, which is greater than that of impoliteness (close to 0, p < .001).

Moderating Effects

Regarding RQ1 and RQ2, we examined interaction effects in Model II in . Although impoliteness, intolerance, and disagreeing discussion are all positively related to perceived incivility, disagreeing discussion attenuates the original effects of impoliteness (B = −0.68, SE = 0.21, p < .001) and intolerance (B = −1.63, SE = 0.21, p < .001) on perceived incivility. As presented in , the difference in perceived incivility between impolite and polite messages is smaller for disagreeing discussions than for agreeing discussions. A simple slope analysis (i.e., given a moderator value, test the strength of the relationship/slope between independent and dependent variables) suggests that the coefficient decreased from 1.54 (agreeing) to 0.86 (disagreeing), though both were significant at the .001 level. The same pattern was observed for intolerance. The coefficient decreased from 1.93 (agreeing) to 1.30 (disagreeing), and the p-values were smaller than .001.

For RQ3 and RQ4, we found no significant effects involving social endorsement cues.

Conditional Indirect Effects

To answer H2 and H4, we estimated the indirect effects of the two variants of online incivility on intentions to silence others via perceived incivility using R’s mediation package based on Model IV and Model V in . The results are presented in . The overall mediation effects for impoliteness and intolerance are positive and statistically significant, further confirming that both online incivility types led to intentions to silence others through perceived incivility, supporting H2 and H4. Regarding H1b, the direct effect of impoliteness on intentions to silence others is not significant (Model III in ), whereas the indirect effect is as expected in H2 (ACME = 0.39, 95% CI = [0.28, 0.51]).

Table 2. Direct and indirect effects of impoliteness and intolerance via perceived incivility on intentions to silence others.

shows that the direct effect of impoliteness on intentions to silence others is significantly negative (ADE = −0.26, 95% CI = [−0.50, −0.02]). However, it is unlikely for disagreeing discussions, which is consistent with the findings in .

Regarding RQ1 and RQ2, the indirect effects of online incivility on intentions to silence others were moderated by discussion stance, too. Similar to the moderation effects on the direct effect, disagreeing discussion significantly attenuates the indirect effects of both impoliteness (from 0.51 to 0.28, p = .016) and intolerance (from 1.00 to 0.47, p = .002) on intentions to silence others. However, we did not find any significant effects of social endorsement (RQ3 and RQ4).

Discussion

In summary, the study reveals that people perceived both impoliteness and intolerance as uncivil, further leading to intentions to silence others. Intolerance had a greater effect on people’s perceptions of incivility and intentions to silence others than impoliteness. Concerning discussion contexts, the direct and indirect effects of impoliteness and intolerance on intentions to silence others through perceived incivility were larger in agreeing discussions than in disagreeing ones, but social endorsement cues did not matter.

Theoretical Implications

First, by extending existing content analytical studies that differentiate two types of incivility (impoliteness and intolerance), we provided empirical evidence that both content features could lead to intentions to silence others via perceptions of incivility. In addition, the results show that people perceive intolerance as more uncivil than impoliteness (see also Kümpel et al., Citation2023), and thus, intolerance has a stronger behavioral effect. The study extends the perception-based approach to classifying incivility (Kenski et al., Citation2020; Muddiman, Citation2017; Stryker et al., Citation2016) by underscoring silencing others as a behavioral standard in understanding online incivility. In other words, communicative acts that could be labeled as incivility should be firstly perceived as uncivil and secondly disapproved by people, even though behavioral outcomes could be caused via other mechanisms, such as emotion (G. Chen & Lu, Citation2017; Masullo et al., Citation2021). Although Bormann et al. (Citation2022) argued that “disapprovals of norm violations are mental processes and are not necessarily linked to an observable reaction” (p.349), our study offers strong evidence that explicit disapproval could be triggered through perceived incivility. This finding renders valuable insights for the emerging scholarship on the behavior of silencing others (Tsfati & Dvir-Gvirsman, Citation2018; Tsfati, Citation2020). It suggests that both impoliteness and intolerance may shift the dynamics of public opinion formation, as people seek to hinder the distribution of such content by silencing it. This sounds an alarm for those who contend that impoliteness, as a tone, could still convey constructive substance and lead people to take part in dynamic (or active) discourses with other political discussants (G. Chen et al., Citation2019; Rossini, Citation2022). At least in the eyes of the public, both impoliteness and intolerance are not desirable and should be suppressed.

Second, previous studies have identified individual factors that alter people’s perceptions of the same uncivil content (Kenski et al., Citation2020); this study demonstrates that discussion context matters in forming such perceptions. More specifically, impoliteness and intolerance in disagreeing discussions exert smaller effects on perceived incivility and silencing intentions than in agreeing discussions. This pattern was also observed in the indirect effects of online incivility on intentions to silence others via perceived incivility. The primary reason is that people generally considered polite and tolerant content far more uncivil in disagreeing conditions than agreeing ones, suggesting that they may interpret civil content as uncivil in disagreeing discussion contexts as well. People are more sensitive to the impoliteness and intolerance expressed in the agreeing discussion context, which aligns with the black sheep effects (Marques et al., Citation1988). Expressing an idea with which an individual agrees in an impolite and intolerant manner can make that individual feel that their own opinions are not adequately represented, thus making their views less likable and approved. While this mechanism has not been typically found in previous research (J. Kim, Citation2018), we reckon that factors such as identity strength and issue involvement could activate this mechanism.

Finally, we did not find any significant effects of social endorsement cues in conditioning the effects of online incivility. There are two plausible explanations. One is that people may deem uncivil content as useless and off-topic, so social endorsement cues could not attenuate the effects of online incivility (Wang et al., Citation2023). Another explanation is that unlike the traditional aggregate discussion context (neighborhood) that involves social interactions and could serve as a reference group (Huckfeldt, Citation2007), people may not consider the online crowd as a meaningful reference group that could guide their judgment of what is uncivil. Future studies may explore the role of social endorsement cues across anonymous forums and non-anonymous social networking sites, the latter of which may contain reference groups that people rely on.

Practical Implications

Given that social media platforms are providing their users with various moderation functions to silence toxic content (Crawford & Gillespie, Citation2016; Naab et al., Citation2018), it is important to note that users should have the basic ability and minimal consensus to identify harmful content. Although our findings support that individuals considered impolite and intolerant content uncivil and tended to silence them, significant bias existed in the process. In disagreeing discussion contexts, people may abuse the reporting functions to silence others simply because of their different opinions, regardless of being civil or not. Platforms need to consider the context of the discussions before accepting users’ recommendations for moderation.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, we used a single-topic experimental design, the results of which cannot be generalized to other issue contexts. In the U.S., issues such as immigration, LGBTQ rights, and climate change are also highly contested and filled with impolite and intolerant discourse. We urge scholars to apply our framework to understand how people evaluate and respond to online incivility revolving around these various issues. Second, while the study provides insights into how people perceive and respond to different forms of online incivility, we caution that the results should be interpreted with prudence. As shown in both the pretest and the main experiment, intolerance manipulation is notably stronger than impoliteness manipulation, which may lead to a ceiling effect for intolerance. The comparisons between strong forms of intolerance and moderate forms of impolite might not be generalized in other situations and thus challenge the validity of our results. Therefore, a more careful operationalization, e.g., choosing intolerant and impolite comments at a similar level of toxicity, is needed in future research. Another important aspect to investigate is the interaction between impoliteness and intolerance in shaping people’s perceptions and intentions to silence others, as both forms of incivility can appear together in online political discussions. Furthermore, the robustness tests did show some heterogeneities (Appendix IV). When it comes to anti-abortion people, the disagreeing discussion context did not attenuate the effects of online incivility on perceived incivility. Given the divide in public attitudes toward these contentious issues, it is promising to incorporate individual predispositions when studying the effects of online incivility across varying discussion contexts. Lastly, intentions to silence others may vary across the broader social and political environments. In countries with higher levels of free speech, silencing others may not be as socially desirable as in countries where censorship is common. We invite scholars to apply our framework to conducting cross-country comparisons.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (3.1 MB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2024.2360596.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shuning Lu

Shuning Lu (PhD, University of Texas at Austin) is Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication at North Dakota State University, USA. Her research focuses on media effects, political communication, and digital journalism.

Hai Liang

Hai Liang (PhD, City University of Hong Kong) is Associate Professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at The Chinese University of Hong Kong SAR. His research interests include political communication and computational social science.

References

- Albarracín, D., & Mitchell, A. L. (2004). The role of defensive confidence in preference for proattitudinal information: How believing that one is strong can sometimes be a defensive weakness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(12), 1565–1584. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271180

- Anderson, A. A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., Xenos, M. A., & Ladwig, P. (2014). The “nasty effect:” online incivility and risk perceptions of emerging technologies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 19(3), 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12009

- Blumell, L. E., Huemmer, J., & Sternadori, M. (2019). Protecting the ladies: Benevolent sexism, heteronormativity, and partisanship in online discussions of gender-neutral bathrooms. Mass Communication and Society, 22(3), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2018.1547833

- Bormann, M., Tranow, U., Vowe, G., & Ziegele, M. (2022). Incivility as a violation of communication norms—A typology based on normative expectations toward political communication. Communication Theory, 32(3), 332–362. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab018

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language use. Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, H. T. (2018). Spiral of silence on social media and the moderating role of disagreement and publicness in the network: Analyzing expressive and withdrawal behaviors. New Media & Society, 20(10), 3917–3936. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818763384

- Chen, G., & Lu, S. (2017). Online political discourse: Exploring differences in effects of civil and uncivil disagreement in news website comments. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 61(1), 108–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2016.1273922

- Chen, G., Muddiman, A., Wilner, T., Pariser, E., & Stroud, N. J. (2019). We should not get rid of incivility online. Social Media+ Society, 5(3), 2056305119862641. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119862641

- Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12104

- Crawford, K., & Gillespie, T. (2016). What is a flag for? Social media reporting tools and the vocabulary of complaint. New Media & Society, 18(3), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814543163

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Row, Peterson.

- Gervais, B. T. (2015). Incivility online: Affective and behavioral reactions to uncivil political posts in a web-based experiment. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 12(2), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.997416

- Gervais, B. T. (2021). The electoral implications of uncivil and intolerant rhetoric in American politics. Research & Politics, 8(2), 20531680211050778. https://doi.org/10.1177/20531680211050778

- Gil de Zuniga, H., Barnidge, M., & Diehl, T. (2018). Political persuasion on social media: A moderated moderation model of political discussion disagreement and civil reasoning. The Information Society, 34(5), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1497743

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512.

- Herbst, S. (2010). Rude democracy: Civility and incivility in American politics. Temple University Press.

- Hilverda, F., Kuttschreuter, M., & Giebels, E. (2018). The effect of online social proof regarding organic food: Comments and likes on Facebook. Frontiers in Communication, 3, 30. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00030

- Huckfeldt, R. R. (2007). Politics in context: Assimilation and conflict in urban neighborhoods. Algora Publishing.

- Hwang, H., Kim, Y., & Kim, Y. (2018). Influence of discussion incivility on deliberation: An examination of the mediating role of moral indignation. Communication Research, 45(2), 213–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215616861

- Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological methods, 15(4), 309. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761

- Kenski, K., Coe, K., & Rains, S. A. (2020). Perceptions of uncivil discourse online: An examination of types and predictors. Communication Research, 47(6), 795–814. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217699933

- Kim, J. (2018). Online incivility in comment boards: Partisanship matters - but what I think matters more. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.015

- Kim, J. W., & Park, S. (2019). How perceptions of incivility and social endorsement in online comments (dis) encourage engagements. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(3), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1523464

- Kümpel, A. S., Unkel, J., & Shen, C. (2023). Differential perceptions of and reactions to incivil and intolerant user comments. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 28(4), zmad018. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmad018

- Lampe, C., Zube, P., Lee, J., Park, C. H., & Johnston, E. (2014). Crowdsourcing civility: A natural experiment examining the effects of distributed moderation in online forums. Government Information Quarterly, 31(2), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2013.11.005

- Liang, H., & Zhang, X. (2021). Partisan bias of perceived incivility and its political consequences: Evidence from survey experiments in Hong Kong. Journal of Communication, 71(3), 357–379. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqab008

- Li, R., & Sundar, S. S. (2022). Can interactive media attenuate psychological reactance to health messages? A study of the role played by user commenting and audience metrics in persuasion. Health Communication, 37(11), 1355–1367. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1888450

- Lu, S. (2020). Taming the news feed on Facebook: Understanding consumptive news feed curation through a social cognitive perspective. Digital Journalism, 8(9), 1163–1180. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1837639

- Lück, J., & Nardi, C. (2019). Incivility in user comments on online news articles: Investigating the role of opinion dissonance for the effects of incivility on attitudes, emotions and the willingness to participate. SCM Studies in Communication and Media, 8(3), 311–337. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2019-3-311

- Lu, S., & Liang, H. (2024). Reactance to uncivil disagreement? The integral effects of disagreement, incivility, and social endorsement. Journal of Media Psychology, 36(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000378

- Lu, S., Liang, H., & Masullo, G. (2022). Selective avoidance: Understanding how position and proportion of online incivility influence news engagement. Communication Research.

- Lu, S., & Luqiu, L. R. (2023). When will one help? Understanding audience intervention in online harassment of women journalists. Journalism Practice, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2023.2201582

- Marques, J. M., Yzerbyt, V. Y., & Leyens, J. P. (1988). The “black sheep effect”: Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420180102

- Masullo, G. M., Lu, S., & Fadnis, D. (2021). Does online incivility cancel out the spiral of silence? A moderated mediation model of willingness to speak out. New Media & Society, 23(11), 3391–3414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820954194

- McClurg, S. D. (2006). Political disagreement in context: The conditional effect of neighborhood context, disagreement and political talk on electoral participation. Political Behavior, 28(4), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-006-9015-4

- Muddiman, A. (2017). Personal and public levels of political incivility. International Journal of Communication, 11, 21.

- Muddiman, A., & Scacco, J. M. (2023). The influence of conflict news on audience digital engagement. Journalism Studies, 25(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2023.2296028

- Mutz, D. C., & Reeves, B. (2005). The new videomalaise: Effects of televised incivility on political trust. American Political Science Review, 99(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051452

- Naab, T. K., Kalch, A., & Meitz, T. G. (2018). Flagging uncivil user comments: Effects of intervention information, type of victim, and response comments on bystander behavior. New Media & Society, 20(2), 777–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816670923

- Papacharissi, Z. (2004). Democracy online: Civility, politeness, and the democratic potential of online political discussion groups. New Media & Society, 6(2), 259–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444804041444

- Peifer, J. T., & Holbert, R. L. (2016). Appreciation of pro-attitudinal versus counter-attitudinal political humor: A cognitive consistency approach to the study of political entertainment. Communication Quarterly, 64(1), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2015.1078828

- Reddit. (2021, September 2). Reddit policy. https://www.reddithelp.com/hc/en-us/categories/360003246511-Privacy-Security

- Rega, R., Marchetti, R., & Stanziano, A. (2023). Incivility in online discussion: An examination of impolite and intolerant comments. Social Media+ Society, 9(2), 20563051231180638. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051231180638

- Rossini, P. (2022). Beyond incivility: Understanding patterns of uncivil and intolerant discourse in online political talk. Communication Research, 49(3), 399–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650220921314

- Schmid, H. J. (2007). Entrenchment, salience, and basic levels. In D. Geeraerts & H. Cuyckens (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of cognitive linguistics (pp. 117–138). Oxford University Press.

- Stryker, R., Conway, B. A., & Danielson, J. T. (2016). What is political incivility? Communication Monographs, 83(4), 535–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2016.1201207

- Sundar, S. S., Jia, H., Waddell, T. F., & Huang, Y. (2015). Toward a Theory of Interactive Media Effects (TIME): Four models for explaining how interface features affect user psychology. In S. S. Sundar (Ed.), The handbook of the psychology of communication technology (pp. 47–86). Wiley Blackwell.

- Tajfel, H. E. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

- Tsfati, Y. (2020). Personality factors differentiating selective approach, selective avoidance, and the belief in the importance of silencing others: Further evidence for discriminant validity. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 32(3), 488–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edz031

- Tsfati, Y., & Dvir-Gvirsman, S. (2018). Silencing fellow citizens: Conceptualization, measurement, and validation of a scale for measuring the belief in the importance of actively silencing others. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(3), 391–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw038

- Van’t Riet, J., & Van Stekelenburg, A. (2022). The effects of political incivility on political trust and political participation: A meta-analysis of experimental research. Human Communication Research, 48(2), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab022

- Wang, S., Chu, T. H., & Huang, G. (2023). Do bandwagon cues affect credibility perceptions? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Communication Research, 50(6), 720–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502221124395

- Wilhelm, C., & Joeckel, S. (2019). Gendered morality and backlash effects in online discussions: An experimental study on how users respond to hate speech comments against women and sexual minorities. Sex Roles, 80(7), 381–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0941-5

- Wojcieszak, M. E., & Mutz, D. C. (2009). Online groups and political discourse: Do online discussion spaces facilitate exposure to political disagreement? Journal of Communication, 59(1), 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01403.x

- Ziegele, M., Naab, T. K., & Jost, P. (2020). Lonely together? Identifying the determinants of collective corrective action against uncivil comments. New Media & Society, 22(5), 731–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819870130