?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The sources and types of information that prospective university students access during the recruitment phase have been widely researched. However, there is limited research on the usefulness of the learning and teaching (L&T) information provided by universities to prospective students in describing their own learning experiences of the programme. The study investigates the meaningfulness of the efforts of HEIs in (1) providing L&T information to prospective students and (2) attending to guidance from government bodies on L&T information that universities should make available to prospective students. Findings based on secondary data analysis of L&T information available for prospective students on 36 university websites and the students’ satisfaction scores of their perceived learning experience whilst on programme indicate that only a small proportion of information provided on university websites reliably reflects the students’ actual learning experience on the programme. Furthermore, the study provides guidance on the L&T information universities should feature on their programme webpages which is likely to be a more realistic indicator of their actual learning experience.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the Western Higher Education (HE) sector has witnessed a funding paradigm shift, moving from state-controlled to a more neo-liberal marketised sector globally where the income of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are dependent on student tuition fees (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, Citation2006; Jongbloed, Citation2003; Tomlinson, Citation2016). Whether HEIs should treat their students as customers is highly contested in the academic communities (Tomlinson, Citation2016). However, HEIs, in their strategic and marketing operations, often approach the recruitment of their so-called customers, the prospective student, as a business. HEIs compete for a larger share of the prospective students, in both internal and external markets. Prospective students, theoretically, have a range of HEI choices provided they are not bound by finance, caring responsibilities or geography. The theory of markets suggests that these prospective students will be distributed efficiently across all HEIs if the HEIs meet the prospective students’ requirements. However, if the prospective students do not have all the available information (often called complete or symmetric information) needed for choice making, then there will be a market failure, that is, the market will be inefficient (Akerlof, Citation1978). HEIs have thus sought to make appropriate learning and teaching (L&T) information available (Binsardi & Ekwulugo, Citation2003; Pucciarelli & Kaplan, Citation2016) to prospective students.

What constitutes appropriate L&T information is a matter of debate. Appropriate L&T information framed through a neo-liberalised lens relates to the dominant pedagogical discourse (sensu Rao et al., Citation2019) of creating and sharing quantitative and qualitative metrics that represent students’ satisfaction as a proxy of teaching excellence (Rao & Hosein, Citation2017; Saunders & Blanco Ramírez, Citation2017). Furthermore, students’ satisfaction is linked to dimensions of teaching quality such as students’ evaluation of their assessment and feedback (Santini et al., Citation2017). Hence, prospective students demand greater availability of L&T information from HEIs (see, for example, Coccari & Javalgi, Citation1995; Johnston, Citation2010; Veloutsou et al., Citation2004) to help them pre-determine their L&T experience of their prospective HEI (Saunders & Blanco Ramírez, Citation2017).

The question arises; are prospective students being ‘sold’ lemons (sensu Akerlof, Citation1978), in the sense of being sold a misrepresented product? Thus, when we say lemons, we want to know whether the current availability of L&T information can help prospective students pre-determine their future satisfaction with their prospective HEI? Or whether the current L&T information available is superfluous (sometimes referred to as non-instrumental information)? These are important questions, as there is surprisingly limited research (see for example Diamond et al., Citation2015; Johnston, Citation2010; Mortimer, Citation1997) on whether the extent the current L&T information available to prospective students has any relationship with their actual satisfaction of the programme, and certainly not from a longitudinal perspective.

Learning and teaching information at HEIs

HEIs invest a significant proportion of their budget towards marketing the teaching excellence information to the students. The selection and availability of this information are predominantly determined by HEIs’ marketing experts and informed by feedback from students and government regulations/guidance. Both current and prospective undergraduate students advise HEIs on the L&T information they want, for example, in the UK, the National Union of Students have done this (NUS, Citation2012). The NUS (Citation2012) found that prospective students wanted information on their contact hours and class size, as they considered this key to their decision-making in course selection. This is not dissimilar to students’ expectations in other countries (see Lai et al., Citation2015).

The quality and quantity of information that the HEIs provide to the prospective students via various information portals (websites, prospectuses, open days, etc.) are perceived as being critical for students to make confident decisions (Diamond et al., Citation2012). Of these, websites are one of the main sources of information (Jan & Ammari, Citation2016; Schimmel et al., Citation2010; Simões & Soares, Citation2010), although increasingly social media is also being used as an important information source (Galan et al., Citation2015; Jan & Ammari, Citation2016). Prospective students from disadvantaged backgrounds, as well as international students, largely depend on websites as they have limited access to sources of information from family and friends (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, Citation2006; Mellors-Bourne et al., Citation2014; Slack et al., Citation2014). Slack et al. (Citation2014) reported that 95% of the students, irrespective of their socio-economic status or whether they were first or second-generation HEI students, access HEI websites and prospectuses for information.

However, students may sometimes distrust information that HEIs provide (Gibbs & Dean, Citation2015; Slack et al., Citation2014); perhaps rightly so, as website information made available by marketing experts is often inclined towards presenting the HEI in a positive light (Rao & Hosein, Citation2017). Therefore, it is likely that the available information on the websites may have very little relevance to the prospective students’ satisfaction with their learning experience. Hence, this paper intends to open a critical discussion on the practice validity of HEIs providing L&T information, by analysing whether the available information has any relationship to the prospective students' actual satisfaction of their learning experience on the programme. Thus, this paper does not seek to explore the factors that influence student experience (such as that by Calvo et al., Citation2010) but instead, it considers how far the web information that is provided to prospective students is representative of their future student experience. Our research question is, therefore:

To what extent is the available learning and teaching information marketed to prospective students on university web pages representative of students’ future satisfaction of their learning experience?

Conceptual Framework

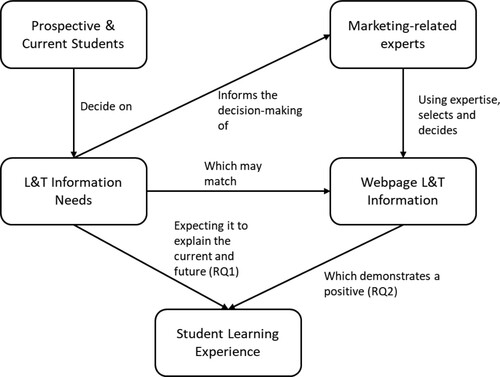

We frame this study within the concept of information choice theory (Koppl, Citation2012; Citation2015). In this theory, experts are not objective truth-seekers but rather the information or expertise they choose to share is value-laden and purposive in order to enhance epistemic outcomes. Information choice theory has three motivational assumptions, firstly that an expert will provide information that maximises their utility, secondly, an expert may consciously or unconsciously deviate from the truth and thirdly, an expert has limited and erring cognition. Therefore, HEI marketing experts, who are responsible for making available L&T information, will fit these motivational assumptions.

Considering the student-as-customer rhetoric, information choice theory suggests that HE marketing experts will be motivated to make available L&T information on web pages that represent a positive HEI brand image (see ) in order to increase their student recruitment (Chapleo et al., Citation2011; Polkinghorne et al., Citation2017; Rao & Hosein, Citation2017). For example, HEIs who are known for having good support for learning and contact time are more likely to make that information available on the web, while universities who have less support and less contact time may not make this information available. Furthermore, the available information is inevitably is based on the current time period, and the extent it relates to the prospective students’ future satisfaction or even the current students’ satisfaction, is uncertain. Therefore, HEI marketing-related experts (such as marketing personnel, programme leaders, faculty deans, etc) will use their professional judgement, based on current graduating students’ satisfaction, to make available the information that persuades the prospective student about their satisfaction with their future learning experience (Rao & Hosein, Citation2017). Furthermore, the information provided by HEI marketing experts is influenced by what students identify as information they need to have in order to have a better purview of their satisfaction with the learning experience at the HEI (for example NUS, Citation2012). However, marketing-related experts are likely to provide asymmetric information, that is, information that does not represent a holistic view of the student future learning experience. This means the selection of information by experts, can sometimes lead to information failure (Akerlof, Citation1978; Koppl, Citation2012). This happens when HEIs marketing experts exclude and/or provide superfluous information (that is non-instrumental information) to prospective students which makes it difficult for them to understand and accurately predict their satisfaction with their future learning experience (Bastardi & Shafir, Citation1998).

Figure 1. The influence of students and marketing-related experts in determining L&T website information (based on Hosein & Rao, Citation2015; NUS, Citation2012; QAA, Citation2013a; QAA, Citation2013b; QAA, Citation2013c; Rao & Hosein, Citation2017).

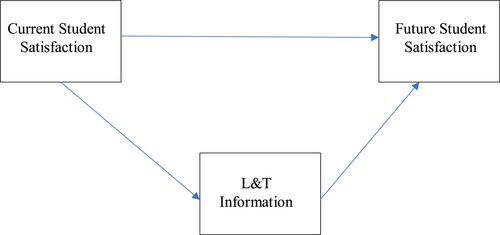

From , two specific research questions are developed:

RQ1: Does the online L&T information available to prospective students accurately reflect what their future learning experience is likely to be? And does the L&T information mediate between current and future student satisfaction?

RQ2: Following from RQ1, if there is a relationship, is there a positive relationship between the availability of online L&T information and students’ satisfaction with their current and/ or future learning experience?

Using these research questions, the model in will be tested. L&T information selected by marketing experts can be influenced by government policies which makes cross-country comparisons of information difficult. Hence, for this study, a single country case study of UK HEIs is used. The next section provides a brief overview of the UK context focussing particularly on the influence of government drivers on the availability of information by UK HEIs marketing experts.

The UK context

In 2010, after the massification of the UK HE sector, an independent review chaired by Lord Browne of Madingley (Browne et al., Citation2010) recommended radical reforms in the UK HEI funding system whereby undergraduates could be charged up to £9000 per annum, an increase of £6000 (Mccaig, Citation2010). Although the steep increase in financial commitment occurred only in England and Wales, the review resulted in the need for all UK HEIs to provide comprehensive information to prospective students to enable informed decision-making (Sheridan & Simpson, Citation2014). The Government also emphasised the requirement for the HEIs to be responsive to the information needs of all its students (BIS, Citation2011). The massification of the UK HE coupled with increasing financial commitments, consequent directives from government bodies and the need to avoid penalisation by the UK Competitions and Marketing Authority (CMA) has created an unprecedented need for the HEIs to prioritise making available appropriate and accurate information to the diverse prospective student body.

Considering these drivers and the Browne review, all HEIs were required to provide standardised information, referred to as the ‘Key Information Set’ (KIS) as mandated by the UK Government (HEFCE, Citation2012). KIS is intended to help prospective undergraduate students to make informed HE choices (Renfrew et al., Citation2010). KIS covers a wide range of information including data on employment, learning and teaching methods, assessments etc. for each degree programme at each HEI. Though KIS provides prospective students with valuable information on the university experience, not all the information that prospective students need for their decision-making process can be presented on a comparable basis that may fit the KIS model (DELNI et al., Citation2015). Further, mature students appear to engage mainly with the KIS data (Gibbs & Dean, Citation2015) and it often does not present all the L&T information perceived as necessary by prospective students (see QAA, Citation2013a, QAA, Citation2013b, QAA, Citation2013c), even though L&T information is one of the key aspects that students consider in their decision-making (Burge et al., Citation2014; DELNI et al., 2015; Veloutsou et al., Citation2004). Given the limitations of the information provided by KIS, HEIs’ marketing-related experts use their own discretion on the additional L&T information they make available on degree programme websites to attract prospective students.

Methods

This study utilises a secondary data analysis approach using a single country case study to address the research questions. Secondary data analysis is a method that uses existing data for answering research questions. Two sets of secondary data were used. The first set of secondary data was drawn from a Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) commissioned study undertaken in May–June of 2015, which surveyed the L&T information of 38 university websites (Hosein & Rao, Citation2015). The longitudinal cross-sectional data drawn from the 2019 National Student Survey (NSS) constituted the second set of data. The NSS measures final year undergraduate students’ satisfaction with their perceived learning experience for each university in the UK. Whilst it does not track each student, the large sample size provides an indication of the average satisfaction of students in each university.

The sample size for this study was determined by the QAA study and the NSS results. In 2019, two HEIs from the original 38 universities in the QAA study did not take part in the NSS survey and hence, the final sample size was 36 HEIs. The QAA study and the NSS data are now briefly explained.

The QAA study: students’ choice of information and website presence

In the QAA study, a stratified random sample of all HEIs within the UK was used. The sample was stratified by the size of the HEI and the overall student satisfaction based on the NSS. Chi-Square analysis showed that the distribution of the stratified random sampling of the 38 universities was representative of the 136 UK HEIs (see Hosein & Rao, Citation2015 for further information on the selection and randomisation procedure). The presence of L&T information on university websites (that did not form part of the mandatory information provided by KIS) was collected on a project commissioned by the UK Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) (see Hosein & Rao, Citation2015). This L&T information was based on three documents published by the QAA that gave guidance on providing information for students on teaching qualifications, class size and student workload (see QAA, Citation2013a, QAA, Citation2013b, QAA, Citation2013c). These documents were informed by and represented students’ views and were based on national student surveys such as from the National Union of Students (NUS) and HEFCE as well as QAA reviews of institutions.

Each document provided several student-informed recommendations on the type of information that HEIs should provide for each degree programme for prospective students. These recommendations were open-coded into fifteen discipline-specific L&T information variables (see and Table A1). An undergraduate student (who represented a prospective student) searched the 38 HEIs’ websites across the two degree programmes (Sociology and Biological Sciences) for 30 min each looking for the fifteen L&T information variables (see Hosein & Rao, Citation2015 for more details). The student’s codings were corroborated with the researchers using two test HEIs (see Hosein & Rao, Citation2015 for more details). The two degree programmes were selected as: firstly, they were both common across all HEIs which meant the data across HEIs were comparable; and secondly, they represented two of the major disciplines (Social Sciences and STEM) for which students may have different information needs.

Table 1. The seven included QAA L&T variables, description and their presence across 38 HEIs (adapted from Hosein & Rao, Citation2015).

If an information variable was available for each degree programme, it was coded 1, and if it was not available, it was coded as 0. Hosein and Rao (Citation2015) noted that except for two variables, the availability of information across the two-degree programmes was similar at universities possibly due to a marketing policy common to both programmes in the universities. Hence, an average of the frequency of the information variables across both degree programmes was used to represent the average availability of that information variable at each HEI. The accuracy of the search was cross-corroborated with interviews from personnel in eight HEIs (Rao & Hosein, Citation2017). Two HEIs indicated that some of the information that was shown as being coded not available could be found online but it may not be straightforward for prospective students as it required them to download the degree programme validation documents [as per personal communication of marketing professionals with researchers].

National student survey (NSS) data

The average NSS scores for the HEI for each of the 36 HEIs were used. Whilst discipline-aggregated NSS scores could have been used, two issues arose. Firstly, for some HEIs the NSS data was not published for disciplines if there were less than ten responses and secondly, it was unclear for some HEIs which NSS discipline classification represented the degree programme. Furthermore, Cheng and Marsh (Citation2010) in their study on one of the NSS item (item related to overall satisfaction) found that whilst there was variability on this item between disciplines, few disciplines differ significantly from the institution’s average. Also, when using the discipline classification, they found that disciplines with small numbers had a lack of reliability in measurement unlike when using all the disciplines in the university. Hence, our approach of using the institution’s NSS scores to represent the average student learning experience at the HEI circumvents this issue of reliability and it also maps on to our approach of using the average availability of L&T information across the two disciplines.

This data has a dual purpose. Firstly, the NSS data represents part of the L&T information that prospective students will have access to (such as on HEI websites or league tables) and secondly, and more importantly, it is used as a proxy for measuring satisfaction of student learning experience. NSS data was collected from 2015 to represent the current satisfaction of the student learning experience, as this data will be most closely related to and inform the QAA L&T information on websites in 2015 made available to prospective students. Secondly, we used NSS data from 2019 to represent future satisfaction with the student learning experience for students who accessed the website L&T information in 2015. This assumes a typical three-year degree programme and that students viewing L&T data in the academic year 2015/2016 will be entering university in 2016.

About the national student survey (NSS)

The original NSS is a validated instrument (see Richardson et al., Citation2007) used annually to ascertain final year undergraduate students’ satisfaction with their learning experience on their degree programmes using seven scales. It is, therefore, a measure of the students’ perception of the quality of their learning experience. The NSS items are measured on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = definitely disagree to 5 = definitely agree).Footnote1 In 2017, the NSS was modified with some scales and items being removed or added (HEFCE, Citation2016). Hence, the 2015 and 2019 NSS scales and items were matched based on similarity. There were five scales and items that were similar for the 2015 and 2019 NSS: Teaching on my course (NSSTC, 3 items); Assessment and Feedback (NSSAF, 4 items); Academic Support (NSSAS, 3 items); Organisation and Management (NSSOrg, 3 items); and Overall Satisfaction (NSSOverall, 1 item). Both 2019 NSSTC and 2015 NSSAF had a reduced set of items but they had a good correlation with their original scales (r ≥ 0.98).

NSSOverall item has been criticised for its appropriateness to measure overall students’ satisfaction (see, for example, Canning, Citation2015), however, Richardson et al. (Citation2007) found a good correlation between this variable and the other student satisfaction variables as well as fair to good reliability for the pilot scales in the original NSS (Cronbach alpha 0.63–0.88). Further, for the newer NSS survey which was used in 2018, HEFCE (Citation2016) found good reliability for all scales (Cronbach alpha more than 0.75).

Analytical approach

A two-stage analytical exploratory approach was undertaken to test the model in . In the first stage, the NSS data from 2015 and 2019 were correlated for 313 HEIs to determine any significant relationships. The fifteen L&T information variables from the QAA study were correlated with the NSS scales from 2015 and 2019 for the 36 HEIs. Seven variables had at least marginal significance (p <0.1) with the NSS scales (Pearson correlations). These seven variables were selected for the next stage of the analysis and their relationships with the NSS scales were noted (see and ).

In the second stage, an exploratory multivariate multiple regression approach was used in SPSS AMOS (version 26) to determine the total direct effects between the seven L&T variables and the five NSS scales for 2015 and 2019. In the initial model, the relationships determined in the correlations were constructed between the L&T variables and the NSS scales (Tables ). The five NSS scales error terms for each year were all set to co-vary as the scales all correlated highly with each other as they are measuring different aspects of the student experience. Further, the L&T information variables error terms were also set to co-vary as their availability may be related to a common marketing policy in the HEI across the various disciplines. The model was improved by removing highly insignificant co-varying relationships (p>0.1). Modification indices were used to determine if there were additional relationships which were not deduced during the correlations between the L&T variables and the NSS scales when considering the total direct effect.

Results

Step one of the analysis reduced the number of QAA L&T variables from fifteen to seven ( and ). Therefore, the presence of eight L&T information variables did not explain future/current student satisfaction. The reduction of the number of variables was unrelated to whether these variables were highly present on HEIs websites. For example, most universities had information on the Anticipated Student Workload (74%), but the presence of this information was not related to any of the satisfaction scales on the student learning experience. The seven L&T variables selected for the second step of analysis ranged in presence from 20% to 75%.

The multivariate multiple regression model based on had reasonable fit (χ2(70) = 59.87, p = .80, CMIN/DF = 0.86; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.09). The SRMR is higher than the suggested cut-off of 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). However, Asparouhov and Muthén (Citation2018) indicated that SRMR usability is limited for small sample sizes and once the chi-square fit holds for small sample sizes (i.e. p > .05 as it is in this model), there is no need to look further into SRMR and other fit indices, as exact fit tests, such as chi-square, are better at indicating model fit than approximate fit tests. Also, the ratio of chi-square statistics to degrees of freedom is less than two, which suggests a good fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). Therefore, we can accept the fit for this model. The Resources and Facilities L&T variable (FACIL) was removed from the final model (see for the standardised total effects) as it had no relationship with the other variables.

Table 2. Standardised Total Effects of the Availability of L&T Information and Student Satisfaction Model across 36 HEIs.

Summary of key findings

Our findings based on :

(1) Research Question 1: Not all of the L&T information provided on university websites are related to the student learning experience. Less than half (6 out of 15) of the L&T variables that students claimed they wanted were related to the current student’s satisfaction with their learning experience and about a tenth (2 out of 15) of the L&T information was able to explain students’ future learning experience satisfaction. Only the variables of CLASS (Class Size) and AS (Type and Amount of Academic Support) were mediating variables between the current and future student learning experience satisfaction.

(2) Research Question 2: The presence of L&T information variables on websites are sometimes negatively related to students’ current and future satisfaction. For example, the presence of the L&T variables CLASS (Class Size) and AS (Type and Amount of Academic Support) information were negatively related to the 2015 (current) NSS scales of Assessment and Feedback (NSSAF).

(3) The 2015 NSS variables (current satisfaction) had better explanatory power to the presence of all six L&T variables. Only the variables of CLASS (Class Size) and AS (Type and Amount of Academic Support) were related to any of the NSS 2019 scales (i.e. future satisfaction).

(4) Interestingly, sometimes the L&T information variables are probably being used to compensate for lower students’ satisfaction. For example, HEIs that had scored lower in the 2015 NSS Academic Support scale (NSSAS15) were more likely to have AS (Type and Amount of Academic Support) information present (−0.756). This suggests that marketing-relating experts may have attempted to compensate for the low scores in NSS outcomes for current students by providing more AS information on their webpages for prospective students.

(5) Unsurprisingly, the corresponding NSS scales from 2015 and 2019 were positively related to each other, for example, the total effect between NSSAF15 and NSSAF19 (Assessment and Feedback) was 0.731. However, there were also some negative relationships between the scales in 2015 and 2019. For example, NSSOrg15 was negatively related to NSSAF19, which suggests that HEIs that had high satisfaction score in Organisation and Management in 2015, would have a lower Assessment and Feedback satisfaction score in 2019.

Discussion

Studies on L&T information made available on HEI websites have focused primarily on the information that prospective students seek to understand their future learning experience in HEIs (see for example HEFCE, Citation2012; Slack et al., Citation2014). The limited research on the HEIs perspective has largely concentrated on the websites’ brand image (Chapleo et al., Citation2011), the information contained within prospectuses (Mortimer, Citation1997) and the reasons behind the lack of L&T information on websites (Rao & Hosein, Citation2017). However, research has not investigated whether there is any value of the information selected and provided by HEIs to prospective students particularly to predict the actual student’s satisfaction with their learning experience on the programme (i.e. when prospective students graduate from the HEI). Our data shows that there is limited practice validity as the L&T information on university webpages mainly represents satisfaction with the current student learning experience (i.e. what is happening at the HEI now). Furthermore, the presence of some L&T information is likely used to demonstrate a positive student learning experience even when it may not exist. Hence, this paper demonstrates through using information choice theory that (1) the information that students claim they want (and which marketing experts provide) minimally explain their satisfaction with the current and future student learning experience and (2) the presence of information that does explain the students’ satisfaction with their current and future learning experience is not always a positive relationship.

From the results, Finding 1, which relates to Research Question 1, suggests that there may be superfluous or non-instrumental information that HEIs are providing with respect to student learning experience satisfaction. There is a disconnect between the information that students seek and what information defines their perceived student learning experience when on the degree programme. HEI marketing-related experts may strategise or feel pressured to provide information that reflects what students suggest they want without knowing whether this information actually reflects the perceived student learning experience (Rao & Hosein, Citation2017; Tomlinson, Citation2013). This is certainly not meant to be any criticism of marketing experts as they have to work within the parameters and the systems they belong to, which are HEI systems that are increasingly moving towards a more neoliberalised and consumer-focused approach. Hence, the feeling of pressure or need to strategise may come from sector-wide rhetoric of prioritising the information needs of the student (i.e. the customer) and mandate from government regulatory bodies strongly advising HEIs to provide more information to their prospective students. However, this may play to students’ internal reward mechanism, where they feel rewarded by collecting non-instrumental information when making decisions (Brydevall et al., Citation2018).

Findings 2 and 4 suggest that marketing-related experts provide L&T information whether knowingly or unknowingly that do not represent a positive satisfaction with the student learning experience (e.g. information on type and amount of academic support and class size). Thus, these marketing-related experts are creating an environment for information failure. Perhaps, HEIs with weaker satisfaction in the student learning experience such as that around academic support may present information that suggests a positively perceived student learning experience even when it is not so (see, for example, interviewee quotations in Rao & Hosein, Citation2017). Thus, prospective students should be wondering whether they are being ‘sold’ a lemon and are being misinformed. Alternatively, it may be that the academic support provided by the HEI is not the type of academic support that leads to students’ satisfaction. For example, the academic support may be generic and not discipline/module-specific or the students’ support is mainly through academic-related professionals such as learning developers and not with the academics (Gravett & Winstone, Citation2018). This demonstrates that to limit the information failure from marketing experts, there should be research evidence to corroborate their judgement in the selection of information that relates specifically to the future student learning experience (Burgman, Citation2015).

Findings 3 and 4 suggest that some information variables are good at explaining the perceived current student learning experience, but the information rarely provides a good preview of prospective students’ satisfaction with their future learning experience. The absence of information was a better indicator of prospective students perceived future student learning experience (Finding 4) as HEIs who failed to put forward information on the amount & type of academic support were associated with a better satisfaction in academic support. In the case of class size, its negative relationship with the 2015 NSS scales of assessment and feedback and 2019 NSS scales academic support seems to be intuitively odd. Small class sizes are generally positively associated with better student outcomes (Kokkelenberg et al., Citation2008) and marketing experts may have promoted website information that is specifically related to small class sizes but may not be representative of the whole programme. For prospective students who are interested in their future overall satisfaction of their learning experience, using the current student satisfaction may be a good practice rather than the L&T variables on the websites. However, the current students’ satisfaction has a fairly weak association with the future satisfaction except for Organisation and Management (0.819) and Assessment and Feedback (0.731); but these two scales appear to have a negative overlap with each other (Finding 5).

Conclusion

In this study, the L&T information is derived from recommendations by the QAA (Citation2013a); (QAA, Citation2013b; Citation2013c) which are based on students’ judgements of their information needs, that is, it is student-informed. Further, whilst the L&T information investigated was information additional to what is included in the KIS, it can provide students with insights as to whether they need to look at additional data during their decision-making process. Furthermore, the information data used in this research was determined by only whether it was present or not and hence more research needs to be conducted in investigating the qualitative value of the information for students’ satisfaction.

As the 36 HEIs were stratified to be representative of UK HEIs, the results in this study could be extrapolated to other UK HEIs as it represents the UK. However, as there is a global trend to market HE to both local and international students (Binsardi & Ekwulugo, Citation2003; Rao & Hosein, Citation2019), particularly for those countries with liberal market economies such as the United States, Australia and Canada (Tomlinson, Citation2016), to remain competitive, HEIs’ marketing-related experts are also providing similar types of information as their British competitors to their prospective students to ensure favourable outcomes (see for example Branco Oliveira & Soares, Citation2016; Simões & Soares, Citation2010). Therefore, the findings from this study can be extrapolated to other HEIs, in particular, that the information provided by HEI market-related experts can be hit or miss in explaining the student learning experience satisfaction, and a vast majority of the information present do not explain the current student learning experience and in almost all cases cannot explain the future student learning experience.

In terms of the methodology, the determination of the presence of L&T information was not an exhaustive web search for L&T information. However, the generous time of 30 min to explore the websites for each programme is more than the average length of visitation for finding information on web pages (just over a minute) (Liu et al., Citation2010) and would be sufficient time to find the main information that marketing experts intend for prospective students to note.

Also, the satisfaction of the student learning experience was measured in the final year of students’ degree which may be affected by immediacy bias effects. However, the NSS is a national survey that was measured across all HEIs at approximately the same time, hence, immediacy bias effects will be random and present for all HEIs. Further, the perceived student learning experience was considered only against five scales and does not consider additional scales of the student learning experience such as personal development (HEFCE, Citation2016).

Finally, the student learning experience, itself, whilst shaped by the university environment (which is represented through the website information) is also dependent on what the student brings and how they engage in the programme. Therefore, any student’s learning experience will be dependent on their own motivations for study and their background which is not captured specifically in this study.

Implications of the study

There are three implications of this research. Firstly, prospective students should not judge HEIs’ current and future student learning experience based on whether the L&T information is present. HEIs without some key L&T information may offer better satisfaction with the student learning experience but may not have expressed this on their websites explicitly.

Secondly, prospective students who wish to predict their satisfaction with their future student learning experience may need to ignore the web pages and look to past student satisfaction only. Thirdly, the L&T information made available on the website more accurately reflects the experience of current students rather than the prospective cohort. However, it is to be noted that despite best efforts, marketing experts can only provide information that represents the current student learning experience and not the future student learning experience (i.e. the learning experience of prospective students during their degree).

Therefore, we have provided evidence to question the validity of this practice as HEIs are presenting information which is based on the cohort which has already chosen them and their data cannot reliably represent the experience for those students who they are trying to attract. Therefore, the presence of a wide range of information to prospective students may be meaningless as the majority of it cannot help them confidently predict the prospective students own satisfaction with their future learning experience.

These findings, therefore, suggest that HEIs should:

(1) Use evidence-based research in deciding the range of information they should provide to students rather than following regulatory bodies’ recommendations whether it be on websites, social media or video channels;

(2) Spend their resources in developing the student experience instead of providing unhelpful information on websites to prospective students which may risk damaging the university’s brand reputation (Gibbs & Dean, Citation2015);

(3) Avoid providing non-instrumental information to students which may make their decision-making process more difficult as it does not impact on their satisfaction with their future student learning experience (Bastardi & Shafir, Citation1998).

However, HEIs are probably providing a wide range of information as a tactical marketing strategy to demonstrate that they are responsive to their customers’ (i.e. the students) information needs and this tactic may help build customership within the current marketised HE context (Ramsey & Sohi, Citation1997). This may be even so if the presence of the information may not be useful to the student customer in contributing to their understanding of the future student learning experience. Perhaps, if HEIs are committed to using the corrosive corporate-speak of marketisation (Katz, Citation2015), then the information provided by HEIs should come with a disclaimer that past student learning experience satisfaction is not a reliable predictor of future student learning experience satisfaction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The NSS datasets only provide the percentage of students in each of the Likert scale for example 60% answering 1 = definitely disagree. To calculate a scale value, the following equation is used:

where i is the Likert scale number; jis the item in NSS scale; n is the total number of items in a NSS scale; P is the percentage of students.

References

- Akerlof, G. A. (1978). The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. In P. Diamond & M. Rothschild (Eds.), Uncertainty in economics (pp. 235–251). Academic Press.

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. Srmr in mplus. http://www.statmodel.com/download/SRMR2.pdf

- Bastardi, A., & Shafir, E. (1998). On the pursuit and misuse of useless information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.19

- Binsardi, A., & Ekwulugo, F. (2003). International marketing of British education: Research on the students’ perception and the UK market penetration. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 21(5), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500310490265

- BIS. (2011). Higher education: Students at the heart of the system. UK Department for Business Innovation Innovation & Skills.

- Branco Oliveira, D., & Soares, A. M. (2016). Studying abroad: Developing a model for the decision process of international students. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(2), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1150234

- Browne, J., Barber, M., Coyle, D., Eastwood, D., King, J., Naik, R., & Sands, P. (2010). Securing a sustainable future for higher education: An independent review of higher education funding and student finance. Department for Business, Innovation & Skills.

- Brydevall, M., Bennett, D., Murawski, C., & Bode, S. (2018). The neural encoding of information prediction errors during non-instrumental information seeking. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 6134. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24566-x

- Burge, P., Kim, C. W., Rohr, C., Frearson, M., & Guerin, B. (2014). Understanding the impact of differential university fees in England. Cambridge.

- Burgman, M. A. (2015). What's wrong with consulting experts? In M. A. Burgman (Ed.), Trusting judgements: How to get the best out of experts (pp. 1–26). Cambridge University Press.

- Calvo, R. A., Markauskaite, L., & Trigwell, K. (2010). Factors affecting students’ experiences and satisfaction about teaching quality in engineering. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 16(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/22054952.2010.11464049

- Canning, J. (2015). Half a million unsatisfied graduates? Increasing Scrutiny of National Student Survey's ‘Overall' question. Educational Developments, 16, (3) 18–20. https://www.seda.ac.uk/resources/files/publications_193_Ed%20Devs%2016.3.pdf.

- Chapleo, C., Carrillo Durán, M. V., & Castillo Díaz, A. (2011). Do UK universities communicate their brands effectively through their websites? Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 21(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2011.569589

- Cheng, J. H. S., & Marsh, H. W. (2010). National student survey: Are differences between universities and courses reliable and meaningful? Oxford Review of Education, 36(6), 693–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2010.491179

- Coccari, R. L., & Javalgi, R. G. (1995). Analysis of students’ needs in selecting a college or university in a changing environment. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 6(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v06n02_03

- DELNI, HEFCE, HEFCW and SFC. (2015). UK review of information about higher education - report on the review of the key information set and unistats. HEFCE.

- Diamond, A., Evans, J., Sheen, J., & Birkin, G. (2015). UK review of information about higher education: Information mapping study: Report to the UK higher education funding bodies. CFE.

- Diamond, A., Vorley, T., Roberts, J., & Jones, S. (2012). Behavioural approaches to understanding student choice. Higher Education Academy.

- Galan, M., Lawley, M., & Clements, M. (2015). Social media's use in postgraduate students’ decision-making journey: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 287–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1083512

- Gibbs, P., & Dean, A. (2015). Do higher education institutes communicate trust well? Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1059918

- Gravett, K., & Winstone, N. E. (2018). ‘Feedback interpreters’: The role of learning development professionals in facilitating university students’ engagement with feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(6), 723–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1498076.

- HEFCE. (2012). Key information sets and unistats: Overview and next steps.

- HEFCE. (2016). Review of information about learning and teaching, and the student experience.

- Hemsley-Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2006). Universities in a competitive global marketplace: A systematic review of the literature on higher education marketing. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 19(4), 316–338. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513550610669176

- Hosein, A., & Rao, N. (2015). An impact study of the guidance documents for higher education providers published by QAA in 2013. Quality Assurance Agency.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jan, M. T., & Ammari, D. (2016). Advertising online by educational institutions and students’ reaction: A study of Malaysian universities. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(2), 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2016.1245232

- Johnston, T. C. (2010). Who and what influences choice of university? Student and university perceptions. American Journal of Business Education (AJBE), 3(10), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.19030/ajbe.v3i10.484

- Jongbloed, B. (2003). Marketisation in higher education, Clark's triangle and the essential ingredients of markets. Higher Education Quarterly, 57(2), 110–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2273.00238

- Katz, L. (2015). Against the corrosive language of corpspeak in the contemporary university. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(3), 554–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.973377

- Kokkelenberg, E., Dillon, M., & Christy, S. (2008). The effects of class size on student grades at a public university. Economics of Education Review, 27(2), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.09.011

- Koppl, R. (2012). Experts and information choice. In R. Koppl, S. Horwitz, & L. Dobuzinskis (Eds.), Experts and epistemic monopolies (pp. 171–202). Emerald publishers.

- Koppl, R. (2015). The rule of experts. In Coyne, C.J. and Boettke, P. (Eds)The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics, (pp. 343–363) Oxford publishers.

- Lai, M. M., Lau, S. H., Mohamad Yusof, N. A., & Chew, K. W. (2015). Assessing antecedents and consequences of student satisfaction in higher education: Evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(1), 45–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1042097

- Liu, C., White, R. W., & Dumais, S. (2010). Understanding web browsing behaviors through weibull analysis of dwell time. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 33rd international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval, in Geneva, Switzerland.

- Mccaig, C. (2010). Access agreements, widening participation and market positionality: Enabling student choice. In M. Molesworth, E. Nixon, & R. Scullion (Eds.), The marketisation of higher education and the student as consumer (pp. 115–128). Routledge.

- Mellors-Bourne, R., Hooley, T., & Marriott, J. (2014). Understanding how people choose to pursue taught postgraduate study. HEFCE.

- Mortimer, K. (1997). Recruiting overseas undergraduate students: Are their information requirements being satisfied? Higher Education Quarterly, 51(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2273.00041

- NUS. (2012). Student experience research. National Union of Students.

- Polkinghorne, M., Roushan, G., & Taylor, J. (2017). Considering the marketing of higher education: The role of student learning gain as a potential indicator of teaching quality. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(2), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2017.1380741

- Pucciarelli, F., & Kaplan, A. (2016). Competition and strategy in higher education: Managing complexity and uncertainty. Business Horizons, 59(3), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.01.003

- QAA. (2013a). Explaining class size. Quality Assurance Agency.

- QAA. (2013b). Explaining staff teaching qualifications. Quality Assurance Agency.

- QAA. (2013c). Explaining student workload. Quality Assurance Agency.

- Ramsey, R. P., & Sohi, R. S. (1997). Listening to your customers: The impact of perceived salesperson listening behavior on relationship outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894348

- Rao, N., & Hosein, A. (2017). The limits of higher education institutions’ websites as sources of learning and teaching information for prospective students: A survey of professional staff. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 21(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2016.1227386

- Rao, N., & Hosein, A. (2019). Towards a more active, embedded and professional approach to the internationalisation of academia. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(4), 35–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1661252

- Rao, N., Mace, W., Hosein, A., & Kinchin, I. M. (2019). Pedagogic democracy versus pedagogic supremacy: Migrant academics’ perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education. 24(5), 599–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1596078

- Renfrew, K., Baird, H., Green, H., Davies, P., Hughes, A., Mangan, J., & Slack, K. (2010). Understanding the information needs of users of public information about higher education. HEFCE.

- Richardson, J. T. E., Slater, J. B., & Wilson, J. (2007). The national student survey: Development, findings and implications. Studies in Higher Education, 32(5), 557–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701573757

- Santini, F. D. O., Ladeira, W. J., Sampaio, C. H., & Da Silva Costa, G. (2017). Student satisfaction in higher education: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2017.1311980

- Saunders, D. B., & Blanco Ramírez, G. (2017). Against ‘teaching excellence’: Ideology, commodification, and enabling the neoliberalization of postsecondary education. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1301913

- Schimmel, K., Motley, D., Racic, S., Marco, G., & Eschenfelder, M. (2010). The importance of university web pages in selecting a higher education institution. Research in Higher Education Journal, 9(1), 1–16. http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/10560.pdf

- Sheridan, A., & Simpson, H. (2014). Reforms in higher education = higher quality provision and better-informed choice? Research in Public Policy - CMPO Bulletin, 17, 8–11. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/cmpo/migrated/documents/higher-education-reform.pdf

- Simões, C., & Soares, A. M. (2010). Applying to higher education: Information sources and choice factors. Studies in Higher Education, 35(4), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903096490

- Slack, K., Mangan, J., Hughes, A., & Davies, P. (2014). ‘Hot’, ‘cold’ and ‘warm’ information and higher education decision-making. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 35(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.741803

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Pearson Education Inc.

- Tomlinson, M. (2013). End games? Consumer-based learning in higher education and its implications for lifelong learning. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 17(4), 124–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2013.832710

- Tomlinson, M. (2016). Student perceptions of themselves as ‘consumers’ of higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(4) 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113856

- Veloutsou, C., Lewis, J. W., & Paton, R. A. (2004). University selection: Information requirements and importance. International Journal of Educational Management, 18(3), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540410527158

Appendix

Table A1. The eight excluded variables, description and their presence across the original 38 HEIs (from Hosein & Rao, Citation2015).

Table A2. Correlations between the 7 L&T variables for the 36 HEIs.

Table A3. Correlations between the 7 L&T variables and the 2015 and 2019 NSS for the 36 HEIs.

Table A4. Correlations between the 2015 and 2019 NSS variables for 313 HEIs.