ABSTRACT

The objective of this study of student-consumers in higher education is to investigate the direct influence of student choice factors on student expectations. The mediating role of perceptions of employability in the relationship between costs of study (fees) and student satisfaction, and the outcome variable of students’ recommendations, is examined in the study based on respondents’ chosen U.K. higher education institution (HEI). The theoretical framework draws on cost-expectation-satisfaction assessment and expectation of employability after graduation. A survey sample of 11,822 respondents and 140 higher education institutions suggests university reputation, course design, service quality, and campus social life directly influence student expectations. Student expectations of choice factors mediate the relationship between the cost of study and satisfaction, and students’ perceptions of employability after graduation mediate the relationship between the cost of study and the likelihood of making a recommendation to peers. The course design was the most influential factor impacting student expectations.

1. Introduction

Globally the higher education (HE) sector has undergone a paradigm shift in terms of governance and state regulation (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, Citation2015), and universities worldwide are experiencing high levels of competition (Musselin, Citation2018), supply and demand challenges (Riddell, Citation2018) changes in funding regimes (Belfield et al., Citation2017) and debates about the efficiency and effectiveness of HE the sector (Antony et al., Citation2019). The increasing worldwide shift towards marketised higher education provision (Richards, Citation2019) generates considerable demand for research on consumer behaviour and choice in HE (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, Citation2016).

English universities ceased to provide free higher education in 2006, and almost all students became fee-paying customers or student-consumers, but with some students awarded bursaries. In 2010 the U.K. government imposed higher tuition fees on all university undergraduate courses up to a maximum of £9,000 (increased to £9250 in 2017) from 2012. (Dunnett et al., Citation2012). As fee-paying student-consumers, they were almost simultaneously responsible for evaluating their experience through a National Student Survey (NSS). All students were invited and strongly urged to complete a student satisfaction survey, resulting in published results and league tables. The introduction of the NSS resulted in a substantial shift in focus by English universities in a drive towards achieving high levels of student satisfaction. In 2013 the U.K. parliament also removed the restrictions or cap on student numbers per institution and substantially enhanced the marketisation of universities across England. These rapid and substantial changes have driven considerable research on student choice and satisfaction in recent years.

The marketised educational climate shapes a learner's beliefs, values, and perceptions, which underlie university satisfaction (Zhao et al., Citation2021) and underpin the student-as-customer perspective when making university choices (Banwait, Citation2021). However, whilst a positive university service culture and reputation sustain favourable satisfaction levels, price or fee increases negatively affect satisfaction (Saleem et al., Citation2017). Jones (Citation2010) also claims that increasing tuition fees, which negatively influences student satisfaction, is due to the disparity between student expectations and experience. Higher fees, therefore, may lead to higher expectations which potentially reduce satisfaction unless all aspects of the student experience are enhanced.

Research by Richards (Citation2019) reveals that students expect practical course design, good support services, and social life and expect their university to maintain a good reputation. High service quality ameliorates the pain of paying fees and enhances satisfaction. First, service quality encompasses activities and facilities such as reputation, library services, catering, accommodation, quality of course design, class size, good teaching, recreational facilities, and student workload. For example, in the context of the hospitality sector, it is widely accepted that service quality and price influence customer satisfaction and determine customer recommendations (Belanche et al., Citation2021). Ammigan et al. (Citation2021) confirm this relationship in the context of international institute recommendations.

Second, research highlights the importance of teaching quality (Berbegal-Mirabent et al., Citation2018) and social life (Kaye & Bates, Citation2017) to student expectations and satisfaction. Those who pay fees are likely to question whether their degree is value for money (Kandiko & Mawer, Citation2013), and fee-paying students are more satisfied when they have good access to support mechanisms (Maxwell-Stuart et al., Citation2018). Extant research, therefore, shows that institutional reputation, social life, course design, customer service are influential factors influencing student expectation-satisfaction relationships because they mitigate adverse effects associated with paying fees.

However, the prior research literature has often been opportunistic, based on single-institution samples (e.g. Stephenson & Yerger, Citation2015) or uses a restricted range of factors such as service quality and customer loyalty from business research (e.g. Saleem et al., Citation2017). Examining many institutional choice factors that may influence service expectations in the relationship between the cost of study and satisfaction is therefore long overdue. This research relies on data from a sizeable multi-institution sample and aims to examine the student choice factors such as institutional reputation, campus social life, course design, customer service as direct influences on student expectation. Within this framework, student expectation mediates the relationship between the cost of study and student satisfaction with a chosen HE institution. None of the studies, to our knowledge, comprehensively examines the role of expectations in light of choice factors ameliorating the pain of paying fees and student satisfaction. To our knowledge, none of the studies has mapped the part of employability, an expectation after graduation, influencing the relationship student recommendation of the institution to their peers. The following section examines key relevant literature and defines critical concepts central to the research.

2. Literature and development of key concepts

The objective of this study of student-consumers in higher education is to investigate the direct influence of student choice factors on student expectation. Within this postulated relationship, the impact of student expectation in the relationship between the cost of study (fees), student satisfaction, and student recommendation outcome was investigated in this study. The theoretical framework draws on cost-expectation-satisfaction assessment and expectations of employability after graduation on the recommendation of the chosen institution.

The study makes a unique contribution to higher education research because the dataset is substantial and students are from 140 universities in the U.K.; sample respondents scored choice factors based on their search process, and factors based on their experience of attending their chosen institution during their first year, and shared perceptions of their future employability. The following section examines the fundamental concepts of students as consumers, student satisfaction models.

2.1. Student as consumers

Research evidence (e.g. Huang, Citation2021) suggests that since becoming consumers, students demand more university support services and better outcomes because paying in exchange for service creates feelings of entitlement. Student-consumers are also more likely to complain about grades and employment prospects, become more career-focused, and expect better employment prospects and higher salaries. Researchers argue that the common goal of studying in HE shifts away from knowledge towards gaining practical skills that align with future employment prospects (Zhai et al., Citation2017). Studies also indicate that student-consumers seek social experiences, service quality, for example, demand more respectful treatment by university employees and administrators. The characteristics HEIs represent the characteristics of service quality to provide customer service. Like services in the hospitality industry that encapsulate intangibility, heterogeneity, and perishability (Hennig Thurau et al., Citation2001), students demand domain-specific knowledge in preparation for their future career and employability (Gruber et al., Citation2010).

Like the profit-making sector, student-consumers of higher education are worthy of investigating participant satisfaction with HEIs. The underlying assumption is that satisfied student-consumers will have a positive attitude towards their HEI, will complete their studies without engaging in switching behaviour. The resultant outcome is to achieve higher graduation rates and would choose the HEI again to study further for a postgraduate degree, similar to repeat purchase behaviour in the commercial business sector (Ham et al., Citation2021; Polas et al., Citation2020). Extant literature in the domain of the service industries (Pizam & Milman, Citation1993; Van Ryzin, Citation2013) recommended using the expectation-disconfirmation theory adopted in this study (Feifei, Citation2021). The authors argue that studying student satisfaction remains a pillar for gauging the success of HEIs in the U.K.

2.2. Expectation – satisfaction models

Satisfaction is described as a cognitive construct (Westbrook & Oliver, Citation1991) and involves affective responses (Yi, Citation1990) as well as behavioural tendencies (Wirtz et al., Citation2000); scholars view satisfaction as a summary of both (Oliver, Citation1993). Student satisfaction in this study refers to a student's favorability of educational outcome and experience based on subjective evaluation (Oliver & DeSarbo, Citation1989). This study takes the perspective that satisfaction is an evaluation process, and it can be cumulatively – evaluated during a long period from enrolment to graduation (Tse & Wilton, Citation1988). The expectancy-disconfirmation theoretical framework identified by (Oliver, Citation1980) is used to study students as consumers (Javed et al., Citation2020). Oliver's expectancy-disconfirmation theory allows gathering students’ evaluation of perceptions relating to which HEI choice factors meet student's expectations. The underlying argument is that the difference in expectations and experience would lead to disconfirmation; when the service expectations exceed the customer expectation, the customer feels satisfied; when the service does not meet the expectation, the customer feels dissatisfied (Oliver, Citation1980). The model is based on the notion that expectations shape satisfaction and results in positive word of mouth or recommendations (Sun et al., Citation2021; Teo & Soutar, Citation2012).

2.3. Factors affecting student expectations-satisfaction

Some observers suggest that student-customer satisfaction is directly influenced by their expectation of the choice factors (Patterson & Johnson, Citation1993; Voss et al., Citation2007). Najimdeen et al. (Citation2021) argue that student-customer expectation indirectly influences customer satisfaction in service quality, whereas other scholars find a direct relationship between student customer expectation and customer satisfaction (Río-Rama et al., Citation2021). Tukiran et al. (Citation2021) conclude that student expectations may, directly and indirectly, impact satisfaction. The current knowledge in the direct relationship between student-customer expectation of choice factors and satisfaction is mixed. Lee and Anantharaman (Citation2013) identified several HEI choice factors affecting student satisfaction included in this study are a) university reputation, b) course design, c) cost of study, d) dealings with the university, and e) social life.

2.3.1. Reputation

The reputation of the HEI is a similar concept to brand image in service quality literature proposed by Zeithaml et al. (Citation1993). In product and service marketing, the image tends to influence customer satisfaction when the information about the product/service is little known, and brand image significantly impacts customer satisfaction (Khalifa et al., Citation2021). In the context of HEIs, reputation is evaluated based on year of establishment, faculty and staff, league table student satisfaction, the number of the first-class graduation, employment after graduation, and alumni association. These factors are significantly different from other service offerings and cumulatively generates a positive word of mouth among students and media that may cause a positive impression about the HEIs in the mind of the student-customer. Studies are supporting a direct relationship between HEIs reputation and a) student expectation (Rofingatun & Larasati, Citation2021); b) satisfaction (Alvis & Rapaso, Citation2007).

2.3.2. Course design

In HEIs, course design refers to structured and relevant learning materials within the virtual learning environment (VLE) platform and resources in the library and the precise mapping between learning objective and learning outcome when the course is delivered face to face mode. The course design may incorporate summative and formative exercises to test students’ knowledge. Brophy (Citation1999) assumes that the structure and coherence of the course design are significant factors for facilitating meaningful learning. Some studies support a direct relationship between good course design and student performance in their summative assessment (Deshields et al., Citation2005). Hartman and Schmidt's (Citation1995) study supports a direct relationship between course design and student satisfaction (Paechter et al., Citation2010). Curtis and Anderson (Citation2021) argues that students experience course design in their first point of contact with their study materials and play a significant role in influencing students’ expectations of their performance outcome.

2.3.3. Dealings with the university

Dealings with a university are conceptualised as the student and university touchpoints, incorporating student-teacher and student-administrators’ interactions within the HEIs. Regarding service industries generally, service quality can be assumed to be correlated with student satisfaction. According to Parasuraman et al. (Citation1988), service quality is an attitude of long-run overall evaluation about service provided by the institution resulting in a widespread expectation about dealings with the university. Within this definition, dealings with the university have similar common ground. Research finds a positive relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction (Polas et al., Citation2020). The service quality literature produces mixed results as to service quality proceeds customer satisfaction (e.g. Bitner, Citation1990); the generally accepted view is that customer service directly influences satisfaction (De Figueiredo Marcos & de Matos Coelho, Citation2021). This study conceptualises dealings with the university as an antecedent forming customer expectation.

2.3.4. Social life on campus

Godofsky et al. (Citation2011) suggests that students view access to and quality of campus services and facilities as social life. In this research, the social life on campus means the social aspects of education and campus facilities related to the physical environment, such as vocational skills, friendships, sports, and participation in extracurricular activities. Osman and Saputra (Citation2019) suggest that the social life on campus can enhance the university's image and attract more students in influencing student expectations of campus life.

2.4. Cost of study and university fees

Borrowing money for fees allows students to postpone higher education costs by spending money from their future income while pursuing HE qualifications. However, drawing down money from future expected income is perceived as more problematic than drawing cash from current assets or established wealth (Thaler, Citation1999). In this research, we assume that student satisfaction is influenced by whether university fees are paid. Students who paid the university fees via a student loan, compared to those using funding from a third party agency (e.g. bursary/ scholarship), are expected to experience a higher level of mental pain with the parting of money, which could negatively affect the student experience.

This research is driven by a desire to understand how the choice factors influence first-year students’ expectations and how student expectation mediates the relationship between the cost of study (fees) and student-consumer satisfaction. The second contribution of this research is unique because it seeks to examine the mediating role of the perceptions of employability in the relationship between the cost of study (fees) and subsequent recommendations by satisfied (or dissatisfied) student-consumers.

The following section sets out the research hypotheses based on the study's specific objectives to examine the role of expectation that mediate the relationship between the financial cost of study and satisfaction.

3. Conceptualisation of hypotheses

Extant literature identifies university choice factors that influence perceptions of student customer expectation (e.g. reputation, social life, course, and dealings with university, resulting in satisfaction and peer recommendations). The relationship is predicted to differ between those who paid university fees via student loan and those who received a bursary/ scholarship to pay the cost of study.

3.1. Reputation and student – consumer expectation

The literature indicates that a favourable university reputation has many benefits in the higher education sector (Berndt & Hollebeek, Citation2019) and shows the quality and expected service quality before experience. Reputation serves as a quality signal that may offset the cost impact; Rofingatun and Larasati (Citation2021) found that reputation directly influences the expectation of service quality and student satisfaction. Research also confirms that a high institutional reputation is positively related to favourable satisfaction levels (Saleem et al., Citation2017). Therefore, we hypothesise that

H1a: There is a direct relationship between student-consumer expectation and perceptions of university reputation

H1b: The perception of reputation on student-consumer expectation will differ between students paying fees with a student loan and students without a student loan.

3.2. Course design and student-consumer expectation

The concept of education quality includes a wide range of variables, including teaching quality, course design, and academic support in learning based on student expectations and perceptions (Pascarella & Terenzini, Citation1991). The quality of course design is a critical factor in education because it enhances academic engagement and achievement (Pitan, Citation2010). Research indicates that course design influences learning strategies creating a safe and stimulating educational environment linked to assessment and grades (Muijs et al., Citation2011). Studies have examined the quality of course design, teaching strategies, practical assessment, communication with students, respect for students, fair review, and friendly attitude towards students. The underlying assumption is that high-quality course design fosters perceptions of high quality of teaching, which leads to positive student expectations. However, perceptions of student expectation of course design are expected to differ for those paying fees than those who receive a bursary or scholarship. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

H2a: There is a direct relationship between student-consumer expectation and course design

H2b: The perception of course design on student-consumer expectation will differ between students paying fees with a student loan and students without a student loan.

3.3. Dealings with university and student-consumer expectation

‘The dealing with university’ encapsulates the university's customer service elements (administration systems) and all the touchpoints that university and students encountered from admission to graduation. The higher education experience has two overlapping areas: evaluating the quality of teaching and learning (Voss et al., Citation2007) and evaluating the quality of the total student experience (Woodall et al., Citation2014). The student experience is the function of services provided by universities, such as administration staff's dealing with students, accommodation, and alumni associations, libraries, and sports clubs. HEIs differ in their approach to student services. Excellent service may dampen the pain of paying fees and increases student satisfaction. Therefore we hypothesise that:

H3a: There is a direct relationship between student-consumer expectation and dealings with the university

H3b: The perception of dealings with the university on student-consumer expectation will differ between students paying fees with a student loan and students without a student loan

3.4. Social life and student – consumer expectation

Social life on campus is related to healthy personal wellbeing, positive emotions influencing improved academic performance, and high student satisfaction (Martin & Dowson, Citation2009). Research by Guay et al. (Citation1999) demonstrates that positive social life on the campus is associated with a positive university experience and positive expectations. These positive relationships of social life on campus may counteract some negative feelings associated with paying university fees and improve HEIs. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

H4a: There is a direct relationship between student-consumer expectation and social life on campus

H4b: The perception of social life in the campus on student-consumer expectation will differ between students paying fees with a student loan and students without

3.5. Satisfaction and student-consumer recommendation

Khalifa and Mahmoud (Citation2016) suggest a positive relationship between student satisfaction and recommendation with an HEI. There is considerable engagement by students in social media in terms of recommendations about their chosen university. Recommendation confirms expectations and leads to student satisfaction (Teo & Soutar, Citation2012). The evidence suggests that recommendations may offset negative perceptions of paying fees; therefore, the recommendation will differ between students paying fees with a student loan and students without a student loan. We hypothesise that:

H5a: There is a direct relationship between student-consumer satisfaction and recommendation

H5b: The perception of recommendation of student-consumer satisfaction will differ between students paying fees with a student loan and students without a student loan

3.6. Mediating role of student -consumer expectation

Woodall et al. (Citation2014) argue that students paying fees in exchange for services display more complaining behaviour and dissatisfaction with HE. On the other hand, Burgess et al. (Citation2018, p. 18) concluded that increased tuition fees in England had no identifiable negative effect on student satisfaction ratings in the NSS survey. They failed to explain why ‘tuition fees increases had no identifiable negative effect on satisfaction’. Marketing literature suggests a negative relationship between increasing price and customer satisfaction (Kumari et al., Citation2021). In higher education, the assumption is that there will be a negative relationship between the cost of study and customer satisfaction. Some studies suggest a direct connection between student-customer expectation and satisfaction (Jones, Citation2010). In line with this reasoning, we hypothesise that:

H6a: Student-consumer expectation mediates the relationship between the cost of study and student satisfaction.

3.7. Mediating role of employability

Graduate salary expectation drives enrolment to university education: those with a university degree expect to earn more, and by obtaining a degree, the probability of finding employment increases (Godofsky et al., Citation2011). Students rely on their degree to gain employment, but they do not rely on HEIs to help them connect with employers. The expectation of employability is increased through attending university; the expectation that some universities that are well-equipped to support students with graduate employment services is like to reduce negative feelings associated with payment of university fees and heightens student satisfaction and likely recommendation to peers. As student-consumer, satisfied students are also more inclined to recommend positive word of mouth to their peers (Najimdeen et al., Citation2021). Therefore, we hypothesise that:

H6b: Employability mediates the relationship between the cost of study and recommendation

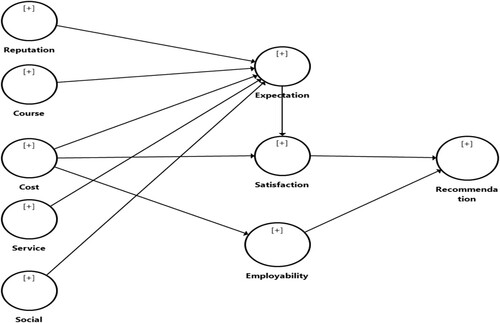

shows the research model for the study showing reputation, course design, cost, dealings with university, social life on campus (antecedent), student-consumer expectation, and perception of employability after graduation (mediators), satisfactions and recommendation (dependent variable/ consequence variables).

4. Methodology

4.1. Research context

The research study encompasses payment of fees, choice factors, and student-consumer expectation and satisfaction in the context of higher education in the U.K. The data was collected through a national survey questionnaire made available online to respondents in their first year of university.

4.2. Sampling and data

Data were collected from 11,822 respondents as part of a national survey of ‘home’ students attending 140 UK higher education institutions through a YouthSightFootnote1 online panel in 2012–13. Youth Sight maintains 140,000-strong’ Opinion Panel Community’ throughout the U.K. and holds a large panel of students for survey purposes. The SPSS database was made available to the authors by YouthSight once the data was no longer commercially viable and includes a comprehensive range of questions relating to demographics, factors in the choice of the university, including attitudes towards and experiences of marketing activities (which is used to compile an annual league table in the U.K.). All those participating in the study are first-year undergraduates attending U.K. higher education institutions (there are no international students in the sample). The most significant number of students from any single institution is 316, and there are 11 universities where fewer than ten respondents completed the survey. All data for this study are self-reported by the respondents during the completion of the online survey. The database contained 416 items under broad headings and cover the following areas: cost of study, student loan, scholarships and grants, UCAS, subject choice, career choice, location, reputation, facilities, financial (costs), institutional attributes, marketing-related (e.g. word of mouth, welcoming, campus visit), and personal reasons.

4.3. Measures

De Jager and Gbadamosi (Citation2010, p. 264) specifically suggested that future student satisfaction studies to consider ‘partial and multiple regression analysis to show the partial and full impact of the identified variables between and among themselves’. Jaroslav et al. (Citation2013) support further examination of the service quality dimensions of higher education and the modelling of university-student satisfaction. This study, therefore, responds to broader calls to study student satisfaction and applies expectation-disconfirmation theory in the relationship between the cost of study and student expectation and satisfaction.

4.3.1. Independent and dependent variables

In examining the relationship between the cost of study and student-consumer expectation and satisfaction, the expectancy disconfirmation constructs put forward by Bhattacherjee (Citation2001) is used as the indicator of satisfaction. Overall expectation and satisfaction is a popular measure in consumer research, a general satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the institution considering all interactions and experiences. This definition represents a holistic approach because it assesses the complete student interaction with the institution; thus, overall student satisfaction was measured using the item: ‘Overall, how would you rate your experience of your university so far?’ (1= very poor / 5=excellent) and one item ‘Does it match the expectations you had before you came here?’ (1=doesn't meet expectations / 5=exceeds expectations).

The independent variable (antecedent) is cost of study. The cost of study is the extent to which an individual or family spend money to study at university. Cost of study includes tuition fees, accommodation, living costs, and entertainment (Bonnema & Van der Waldt, Citation2008). All items for nine factors (namely cost of study, reputation, social life, course, employability, dealing with the HE and recommendation) were measured using a 1–5 scale on the Youth Sight online panel database: 1 = strongly disagree / 5 = strongly agree. summarises the item description, factor loading and convergent validity for the nine factors.

Table 1. Convergent validity indexes.

Rossiter (Citation2002) highlights the importance of using a measure of agreement between the individuals or raters, and therefore, twenty students (10 postgraduate and ten undergraduates from British Universities) were asked to rate all the items in the research instrument to assess content and face validity, representativeness, dimensionality, comprehensibility and un-ambiguity. The inter-rater agreement between two groups of students was calculated, and the result produced strong Cohen's kappa coefficient .80, p < .0001, which considered moderate to substantial agreement.

4.4. Analysis technique

For analysis, the researchers use partial least squares (PLS) path methodology and implement structural equation modelling (SEM) with Smart PLS version 3.2.8. This approach was chosen because it has less strict requirements on multivariate conditions, sample size and residual distribution than the covariance-based SEM technique. Before conducting any type of analysis, basic data screening activities were carried out to ensure the accuracy of data entry and assess the normality of continuous variables. Missing data were replaced using the mean of the items from the subscale. The data were inspected for outliers, defined as values greater than 3.5 standard deviations from the sample mean for each variable. Measurement model assessment was conducted before assessing the structural model fit and hypothesis testing. A bootstrapping procedure with replacement using 5,000 subsamples to calculate the statistical significance of the parameter estimates was also carried out. The measurement model and structural model was tested, and PLS Multi-Group Analysis (PLS-MGA) was used to test if students who paid fees and scholarship and bursary enrolments are significantly different in their specific parameter estimates.

5. Results

5.1. Demographic profile

The total number of respondents used for the analysis (n = 11822) were predominantly female (female 66%; male 33%); and white 81% (Asian 10%, Black 4%, other 5%). The respondents were mainly traditional school-leaver undergraduates: 77% were aged 19 or under (aged 20–25 16%, aged 26 or older 7%); Most were middle class: the social class was measured using two categories ABC1 (62%) and CDE2 (28%) other (10%). The majority of students (76.2%) were paying U.K. fees without a bursary, and 23.8% had been awarded bursaries or funding to offset fees from their university.

5.2. Measurement properties

The factor analysis, incorporating the Varimax rotation, was used to evaluate the validity of the measurement (KMO=0.932; Sig. = 0.000). Internal consistency reliability was tested, and the Cronbach alpha results supported the dimensional concepts and provided the fullest evidence of construct validity. To investigate convergent and discriminate validity, composite reliability (C.R.) and average variance extracted (AVE) indexes were also examined. The AVE of each construct was larger than 0.5 and C.R. was larger than 0.7. Thus, the analysis confirmed that the items measured only one construct, and convergent validity was satisfied (). Discriminant validity was satisfactory using Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion. We have presented in the Hetrotrait-Monotrait Ratio -HTMT validity index where HTMT values are below 0.90, hence discriminant validity established between reflective indicators following Henseler et al. (Citation2015) (See ). Finally, common method variance (CMV) was tested. Hartman's single factor technique showed that the single factor explained 0.3 of total variance. As the total variance explained was less than 0.5, the measurement confirmed a minimum CMV likelihood.

Table 2. Discriminant validity index (Hetrotrait-Monotrait Ratio -HTMT).

5.3. Assessment of structural model and hypothesis testing

The PLS method was used to confirm the hypothesised relations between constructs in the proposed model. The significance of the paths included in the proposed model was tested using a bootstrap resampling procedure. In assessing the PLS model, the squared multiple correlations (R2) for each endogenous latent variable were initially examined, and the significance of the structural paths was evaluated. The proposed relationships are supported if the corresponding path coefficients had the proposed sign and were significant. The results of hypotheses testing for H1-H6 are shown in .

Table 3. Model’s path coefficients (standardised estimates).

5.4. Cost of study and student -consumer expectation and satisfaction

The results show that R2 was 10% for student-consumer expectation and 34% for satisfaction and employability 7%, and recommendation 8% (‘Substantial predictive relevance’ was identified ‘for student-consumer expectation’). Stone-Geisser's cross-validated redundancy score, similar to R2, is Q2 > .0. The calculated global goodness of fit (GoF) exceeding the recommended threshold of GoF > 0.36 (Wetzels et al., Citation2009). These results confirm the predictive relevance of the student-consumer expectation and satisfaction model. The effect size of student-consumer expectation on student satisfaction was .48, and the model fitness scored normed fit index (NFI) 0.72; standardised root means square residual (SRMR) was .14 suggesting good model fit.

The university reputation, social life, course, and dealings with the university are contributors to student-consumer expectations. The direct effect, significance, magnitude, and mediation effect in . All hypotheses (H1a, H2a, H3a, H4a, H5a, H6a) are fully supported.

Table 4. Multi-group comparison of fees with a loan and students without a loan on expectation.

Results support the influential role of the choice factors such as university reputation, social life, course, and dealings with university contribute to influence student expectation and offset the effect of paying university fees. The result converges that consumer expectation of choice factor will directly affect perceived performance as demonstrated in marketing (Johnson et al., Citation1998), hospitality and tourism (Pizam & Milman, Citation1993) and in website service quality (Biswas et al., Citation2019). The result is consistent with studies that student satisfaction in colleges is strongly influenced by student expectations (Patterson & Johnson, Citation1993; Rolfe, Citation2002). Jones (Citation2010) affirms that students expect more from their university experience, resulting in greater dissatisfaction in the disparity between expectations and experiences. This student-consumer expectation positively mediates the relationship between the cost of study and student satisfaction with a chosen university. The result reveals that students in England at the data collection seem to have a high level of expectation from the HE institutions. Student-consumer expectation offsets some of the adverse effects of higher fees, whereby students remain satisfied with the HEI.

The result of this study highlight that employability plays a mediating role between the cost of study and expectation and satisfaction; the satisfied students tend to recommend their HEIs to their peers (Khalid & Ahmad, Citation2021). The mediating effect of employability is consistent with studies that traced the impact of the increase in the cost of study and student-consumer expectation of employability. For example, Bates and Kaye (Citation2014) compared the expectations and experiences of first-year psychology students before and after the change in tuition fees and found minimal support for the idea that students had heightened expectations except for employability; those students paying higher fees held greater expectations for their employment prospects following graduation.

The choice factors directly and positively influenced student-consumer expectations (see ). The student-consumer expectation positively mediates the effect of cost of study and overall satisfaction. The direct relationship between the cost of study and overall satisfaction is positive in our study, suggesting that positive perception of choice factors of the HEIs resulted in positive student-consumer expectation, which seems to ameliorate some of the adverse effects of cost of study on satisfaction rates. This result is significant as it highlights an important point that when HEIs incorporate a higher level of service, good course design, social life and reputation for the campus mitigate some adverse effects of the increased cost of study. Therefore, our research shows a positive relationship between the cost of study and student-consumer expectation.

Additionally, the results of this study reveal that the perception of employability mediates the relationship between the cost of study and student satisfaction, resulting in the recommendation of the HEIs. These results align with findings in the Godofsky et al. (Citation2011) study. Students rely on their degree to gain employment, and they do not expect HEIs to help make connections with employers, but they rely on external information from the industry to understand the employability of the graduating students from the HEIs. Though, students do not see HEIs as responsible for job searches and employment, but rather for providing the skills and knowledge that enable them to be employable (Dekker et al., Citation2021).

A multi-group analysis was conducted to assess whether the mediators of this study differ between students paying fees with a student loan and students without a student loan.

5.5. Multi-Group analysis

A multi-group analysis compared the results for two student groups, namely those who pay university fees via student loan and students without a loan. A parametric and non-parametric test was performed to assess the differences in the critical paths between the models and to assess further the possible mediation effect of hypothesised factors (See ). Column P-values were obtained applying the method proposed by Chin (Citation2000). This method assumes that data is usually distributed and that the variance of two groups is similar, which was the case in this dataset. A non-parametric test (Sarstedt et al., Citation2011) P-value column presents the p-value obtained applying the Henseler test that p-value < than .05 and > .95 indicate differences between groups on the path model. The result of these two tests was similar. A significant difference was found between the groups of students based on how they pay for university fees. The perceptions of social life on campus and student-consumer expectations differed. Therefore hypotheses H1b, H2b, H3b, H5b, H6b are rejected: there is no difference in these choice factors by the student-consumer expectations between the two groups. The result reveals that students paying fees with and without a student loan differ in their views about social life on campus; therefore, H4b is accepted.

6. Discussion

The results suggest that universities that pursue improvements focusing on social life, up-to-date courses, student services, and high reputation are likely to enhance student expectations of these factors, which reduce the adverse effects of paying university tuition fees, high living costs, and other associated costs university education. (Though, in our study, we did not measure the adverse effect of an increase in fees on student-consumer expectation and their satisfaction.) The result is consistent regarding choice factors and their influence on student-consumer expectation and satisfaction: i.e. university reputation (Alvis & Rapaso, Citation2007; Navarro et al., Citation2005); dealings with university and service quality (Hartman & Schmidt, Citation1995; Huang, Citation2021); social life on campus (Asiabaka, Citation2008; Kok et al., Citation2011); perception of employability (Barton et al., Citation2019); course design (Navarro et al., Citation2005); and student satisfaction. This study confirms that the linkage between student satisfaction and student recommendation is explained well via student-consumer expectation of the choice factors of HEIs.

The following crucial mediating factor considered a critical factor in student satisfaction and future recommendation is the perception of employability after graduation. There is evidence that the cost of tuition fees is associated with enhanced perceptions of prospective graduate employment (e.g. Moore et al., Citation2012). The U.K. economic climate and employment prospects are a concern to all. Therefore, it is understandable that students believe their investment in their higher education will pay off after graduation. The findings of this study highlight that those students who take out loans versus those with a bursary have a similar expectation of the choice factors, except social life on campus, which is illuminating and require further study, now that all students take a loan for fees.

7. Conclusion

The objective of this study was to address the need for a holistic approach to investigating the role of student choice factors (course design, social life, reputation, and dealings with university) in the relationship between the cost of study (fees) and overall student-consumer expectation with a chosen university. The findings indicate that the direct connection between the cost of study (fees) and overall satisfaction is positive: as the cost of study (fees) increases, student satisfaction decreases. However, student expectations of choice factors mediate the relationship between the cost of study and satisfaction; and students’ perceptions of employability after graduation mediate the relationship between the cost of study and the likelihood of making a recommendation to their peers. The course design was the most influential factor impacting student expectations. Students assess cost and benefit based on institutional reputation, campus life, course, and service quality at their chosen university. These results are consistent with prior literature that supports the notion that students view the cost of study either as investment or debt (Callender & Jackson, Citation2008).

The findings of this study are crucial for understanding how students assess increased costs (e.g. tuition fees) and the impact of the expenses on student-consumer expectation and satisfaction. The study's contribution to higher education literature is twofold. First, the results have shown that an increase in tuition fees does not necessarily undermine student-consumer expectation of choice factors in increasing satisfaction with chosen HEIs: social life on campus, up-to-date courses, a high reputation, and delivering high service quality do reduce the adverse effects associated with increases in tuition fees. Second, the researchers comparing two aspects of satisfaction: overall and expectancy confirmation. The study is unique because it highlights that student-consumer expectation of the choice factor did not differ between the student group who paid fees taking out loans compared to students who had not (including students with bursaries) to cover the total cost of their HE.

7.1. Managerial and practical implications

Since the survey was conducted, tuition fees in England have been introduced for all home students, and therefore no bursary can reduce the burden of debt. The effect of the cost of study has thus shifted so that the negative impact of the fees is now very high, and the implications for student-expectation of choice factor is high influencing satisfaction is likely to be greater, with reduced chance of reducing that effect through mediating effects of the perceptions of employability and conforming to student expectations tested in this study.

However, research findings can be used at different levels to inform organisational and managerial processes to guide universities for continuous improvement. The role of social life on campus and the importance of up-to-date course programmes, institutional reputation and service quality are crucial for attaining or even maintaining higher levels of student satisfaction. Perhaps the most critical factor in reducing the effects of high fees is university reputation: a high reputation. Universities need to focus on their particular reputation, which requires a strategic marketing approach. This can be challenging for some institutions – where league tables have driven what counts as a good reputation.

For researchers, the model examined in this study has not integrated environmental factors that may potentially moderate the cost of study and student-consumer expectation and satisfying relationship. This creates an opportunity for further research in this area by examining their effects in the relationships between cost of study and student satisfaction.

Future research might be conducted using similar variables and a similar dataset, but with students paying total fees at the current rate. The survey items would need to match the original database to provide an opportunity for comparison with students who were paying lower fees.

7.2. Limitations and future research

This research has several limitations that should be taken into account. First although the data is unique, substantial and comprehensive, it is historical and does not consider the significant rise in fees from 2012. However, all students after 2012 had taken on debt, and there was less chance of making comparisons with those not paying fees. Second, the sample for this research has been drawn using convenience sampling technique – or rather an ‘opt-in’ approach where students volunteered to join a panel. Third, the survey instrument was not designed specifically for this study, and therefore, the research model and the variables were selected based on data already collected.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 YouthSight is part of the Opinion Panel community (http://www.youthsight.com/). The Opinion Panel Community is the UK’s largest access panel of young people and students.

References

- Alvis, H., & Rapaso, M. (2007). Conceptual model of student satisfaction in higher education. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 18(5), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783360601074315

- Ammigan, R., Dennis, J. L., & Jones, E. (2021). The differential impact of learning experiences on international student satisfaction and institutional recommendation. Journal of International Students, 11(2), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v11i2.2038

- Antony, J., Karamperidis, S., Antony, F., & Cudney, E. A. (2019). Understanding and evaluating teaching effectiveness in the UK higher education sector using experimental design: A case study. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 36(2), 202–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-01-2018-0011

- Asiabaka, I. P. (2008). The need for effective facility management in schools in Nigeria. New York Science Journal, 1(2), 10–21.

- Banwait, K. (2021). The student as customer: A study of the intensified marketisation of higher education in England (Doctoral dissertation, University of Derby).

- Barton, G., Hartwig, K., & Le, A. H. (2019). International students’ perceptions of workplace experiences in Australian study programs: A large-scale survey. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(2), 248–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318786446

- Bates, E. A., & Kaye, L. K. (2014). Exploring the impact of the increased tuition fees on academic staffs’ experiences in post-92 universities: A small-scale qualitative study. Education Sciences, 4(4), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci4040229

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Pérez-Rueda, A. (2021). The role of customers in the gig economy: How perceptions of working conditions and service quality influence the use and recommendation of food delivery services. Service Business, 15(1), 45–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-020-00432-7

- Belfield, C., Britton, J., Dearden, L., & Van Der Erve, L. (2017). Higher Education funding in England: Past, present and options for the future: IFS Briefing Note BN211.

- Berbegal-Mirabent, J., Mas-Machuca, M., & Marimon, F. (2018). Is research mediating the relationship between teaching experience and student satisfaction? Studies in Higher Education, 43(6), 973–988. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1201808

- Berndt, A., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2019). Brand image and reputation development in higher education institutions. In B. Nguyen, T. C. Melewar, & J. Hemsley-Brown (Eds.), Strategic brand management in higher education (pp. 143–158). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429029301

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance. An expectation–confirmation model. MIS Quarterly, 25(3), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250921

- Biswas, K. M., Nusari, M., & Ghosh, A. (2019). The influence of website service quality on customer satisfaction towards online shopping: The mediating role of confirmation of expectation. International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration, 5(6), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.18775/ijmsba.1849-5664-5419.2014.56.1001

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54(April), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400206

- Bonnema, J., & Van der Waldt, D. L. R. (2008). Information and source preferences of a student market in higher education. International Journal of Educational Management, 22(4), 314–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540810875653

- Brophy, J. E. (1999). Teaching: Educational Practices Series, Vol. 1. https://www.ibe.unesco.org/publications/educationalpracticesseriespdf/prac01e.pdf

- Burgess, A., Senior, C., & Moores, E. (2018). A 10-year case study on the changing determinants of university student satisfaction in the U.K. Plos One, 13(2), e0192976. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192976

- Callender, C., & Jackson, J. (2008). Does the fear of debt constrain choice of university and subject of study? Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 405–429.

- Chin, W. (2000, December). Partial least squares for I.S. researchers: an overview and presentation of recent advances using the PLS approach. In ICIS (Vol. 2000, pp.741–742).

- Curtis, N. A., & Anderson, R. D. (2021). Moving toward student-faculty partnership in systems-level assessment: A qualitative analysis. International Journal for Students as Partners, 5(1), 57–75. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v5i1.4204

- De Figueiredo Marcos, A. M. B., & de Matos Coelho, A. F. (2021). Service quality, customer satisfaction and customer value: Holistic determinants of loyalty and word-of-mouth in services. The TQM Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-10-2020-0236

- De Jager, J., & Gbadamosi, G. (2010). Specific remedy for specific problem: Measuring service quality in South African higher education. Higher Education, 60(3), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9298-6

- Dekker, I., Chong, C. F., Schippers, M., & van Schooten, E. (2021). The Right Job Pays; Effects of Student Employment on the Study Progress of Pre-service Teachers (No. ERS-2021-004-LIS).

- Deshields, Jr., O. W., Kara, A., & Kaynak, E. (2005). Determinants of business student satisfaction and retention in higher education. International Journal of Education al Management, 19(2), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540510582426

- Dunnett, A., Moorhouse, J., Walsh, C., & Barry, C. (2012). Choosing a university: A conjoint analysis of the impact of higher fees on students applying for university in 2012. Tertiary Education and Management, 18(3), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2012.657228

- Feifei, L. (2021). Construction of international student satisfaction model under the internationalization of higher education: New normal perspective. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(11), 6084–6098. https://turcomat.org/index.php/turkbilmat/article/view/6927/5686

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Godofsky, J., Zukin, C., & Van Horn, C. (2011). Unfulfilled expectations: Recent college graduates struggle in a troubled economy. Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers University.

- Gruber, T., Fuß, S., Voss, R., & Gläser-Zikuda, M. (2010). Examining student satisfaction with higher education services: Using a new measurement tool. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23(2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551011022474

- Guay, F., Boivin, M., & Hodges, E. V. (1999). Predicting change in academic achievement: A model of peer experiences and self-system processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 105. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.91.1.105

- Ham, S., Lee, K. S., Koo, B., Kim, S., Moon, H., & Han, H. (2021). The rise of the grocerant: Patrons’ in-store dining experiences and consumption behaviors at grocery retail stores. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 102614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102614

- Hartman, D. E., & Schmidt, S. L. (1995). Understanding student/alumni satisfaction form a consumers. Perspective, Research in Higher Education, 36(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02207788

- Hemsley-Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2015). Higher education consumer choice. Palgrave.

- Hemsley-Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2016). Context and concepts of higher education consumer choice. In J. Hemsley-Brown & I. Oplatka (Eds.), Higher education consumer choice (pp. 14–43). Palgrave Pivot.

- Hennig Thurau, T., Langer, M. F., & Hansen, U. (2001). Modeling and managing student loyalty: Anapproach based on the concept of relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 3(4), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/109467050134006

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

- Huang, C. F. (2021). Positioning students as consumers and entrepreneurs: Student service materials on a Hong Kong university campus. Critical Discourse Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2021.1945471

- Jaroslav, D., Petrovicová, J. T., Dejan, R., & Rajic, T. (2013). Linking service quality and satisfaction to behavioural intentions in higher education setting. Ekonomicky Casopis, 61(6), 578–596.

- Javed, M., Hock, O. Y., Asif, M. K., & Hossain, M. I. (2020). Assessing the impact of emotional Intelligence on job satisfaction among private school Teachers of Hyde rabad, India. International. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(4), 5035–5045. https://doi.org/10.37200/IJPR/V24I4/PR201603

- Johnson, D., Johnson, R., & Smith, K. (1998). Cooperative learning returns to college. Change, 30(4), 26–35.

- Jones, G. (2010). Managing student expectations: The impact of top-up tuition fees. Perspectives, 14(2), 44–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603101003776135

- Kandiko, C. B., & Mawer, M. (2013). Student expectations and perceptions of higher education. King's Learning Institute.

- Kaye, L. K., & Bates, E. A. (2017). The impact of higher fees on psychology students’ reasons for attending university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41(3), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2015.1117597

- Khalid, K., & Ahmad, A. M. (2021). The relationship between employability skills and career adaptability: A case of undergraduate students of the United Arab Emirates. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning Comment.

- Khalifa, B., & Mahmoud, A. B. (2016). What forms university image? An integrated model from Syria. Business: Theory and Practice, 17(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2016.560

- Khalifa, G. S., Binnawas, M. S., Alareefi, N. A., Alkathiri, M. S., Alsaadi, T. A., Alneadi, K. M., & Alkhateri, A. (2021). The Role of Holistic Approach Service Quality on Student's Behavioural Intentions: The Mediating Role of Happiness and Satisfaction. Https://www.city.edu.my/cuejar/pdf/Volume3Issue1/cuejarv3i1_02.pdf

- Kok, H. B., Mobach, M., & Omta, O. (2011). The added value of facility management in the education environment. Journal of Facilities Management, 9(4), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1108/14725961111170662

- Kumari, P., Kumar, S., & Itani, M. N. (2021). Scale development of customer satisfaction with complaint handling and service recovery in an e-commerce setting. Journal for Global Business Advancement, 14(3), 383–407. https://doi.org/10.1504/JGBA.2021.116722

- Lee, J., & Anantharaman, S. (2013). Experience of control and student satisfaction with higher education services. American Journal of Business Education, 6(2), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.19030/ajbe.v6i2.7684

- Martin, A. J., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 327–365. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325583

- Maxwell-Stuart, R., Taheri, B., Paterson, A. S., O'Gorman, K., & Jackson, W. (2018). Working together to increase student satisfaction: Exploring the effects of mode of study and fee status. Studies in Higher Education, 43(8), 1392–1404. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1257601

- Moore, J., Mcneill, J., & Halliday, S. (2012). Worth the price? Some findings from young people on attitudes to increases in university tuition fees. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 13(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.5456/WPLL.13.1.57

- Muijs, D., Kelly, A., Sammons, P., Reynolds, D., & Chapman, C. (2011). The value of educational effectiveness research–a response to recent criticism. Research Intelligence, 114(24), 24–25. http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/336165

- Musselin, C. (2018). New forms of competition in higher education. Socio-Economic Review, 16(3), 657–683. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy033

- Najimdeen, A. H. A., Amzat, I. H., & Ali, H. B. M. (2021). The impact of service quality dimensions on students’ satisfaction: A study of International students in Malaysian Public universities. IIUM Journal of Educational Studies, 9(2), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.31436/ijes.v9i2.324

- Navarro, M. M., Iglesias, M. P., & Torres, P. R. (2005). A new management element for universities: Satisfaction with the offered courses. International Journal of Educational Management, 19(6), 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540510617454

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). Acognitivemodel of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

- Oliver, R. L. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 418–430. https://doi.org/10.1086/209358

- Oliver, R. L., & DeSarbo, W. S. (1989). Processing satisfaction response in consumption: A suggested framework and research proposition. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction, and Complaining Behavior, 2(1), 1–16.

- Osman, A. R., & Saputra, R. S. (2019). A pragmatic model of student satisfaction: A viewpoint of private higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 27(2), 142–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAE-05-2017-0019

- Paechter, M., Maier, B., & Macher, D. (2010). Students’ expectations of, and experiences in e-learning: Their relation to learning achievements and course satisfaction. Computers & Education, 1(1), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.08.005

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How college affects students: Findings and insights from twenty years of research. Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers.

- Patterson, P. G., & Johnson, L. W. (1993). Disconfirmation of expectations and the gap model of service quality: An integrated paradigm. Journal of Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 6(1), 90–99.

- Pitan, O. S. (2010). Assessment of skills mismatch among employed university graduates in Nigeria labour market [Doctoral dissertation, University of Ibadan].

- Pizam, A., & Milman, A. (1993). Predicting satisfaction among first-time visitors to a destination by using the expectancy disconfirmation theory. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 12(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-4319(93)90010-7

- Polas, M. R. H., Juman, M. K., Karim, A. M., Tabash, M. I., & Hossain, M. I. (2020). Do service quality dimensions increase the customer brand relationship among Gen Z? The mediation role of customer perception between the service quality dimensions (SERVQUAL) and brand satisfaction. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(4), 1050–1070.

- Richards, T. N. (2019). An updated review of institutions of higher education's responses to sexual assault: Results from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(10), 1983–2012. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516658757

- Riddell, S. (2018). Higher education in the developed world: Common challenges and local solutions. In S. Riddell, S. Minty, E. Weedon, & S. Whittaker (Eds.), Higher education funding and access in International perspective (pp. 241–252). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Río-Rama, D., de la Cruz, M., Álvarez-García, J., Mun, N. K., & Durán-Sánchez, A. (2021). Influence of the quality perceived of service of a higher education center on the loyalty of students. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(671407), 2034. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.671407

- Rofingatun, S., & Larasati, R. (2021). The effect of service quality and reputation on student satisfaction using service value as intervening variables. The International Journal of Social Sciences World, 3(01), 37–50. https://www.growingscholar.org/journal/index.php/TIJOSSW/article/view/88

- Rolfe, H. (2002). Students demands and expectations in an age of reduced fina ncial support: The perspectives of lecturers in four English universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 24(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080022000013491

- Rossiter, J. R. (2002). The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19(4), 305–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(02)00097-6

- Saleem, S. S., Moosa, K., Imam, A., & Khan, R. A. (2017). Service quality and student satisfaction: The moderating role of university culture, reputation and price in the education sector of Pakistan. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 10(1), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijms.2017.217335.672304

- Sarstedt, M., Henseler, J., & Ringle, C. M. (2011). Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. In M. Sarstedt, M. Schwaiger, & C. R. Taylor (Eds.), Measurement and research methods in international marketing (pp. 195–218). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Stephenson, A. L., & Yerger, D. B. (2015). The role of satisfaction in slumni perceptions and supportive behaviors. Services Marketing Quarterly, 36(4), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332969.2015.1076696

- Sun, X., Foscht, T., & Eisingerich, A. B. (2021). Does educating customers create positive word of mouth? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 102638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102638

- Teo, R., & Soutar, G. N. (2012). Word of mouth antecedents in an educational context: A Singaporean study. International Journal of Educational Management, 26(7), 678–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378802500209

- Thaler, R. H. (1999). Mental accounting matters. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12(3), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(199909)12:3<183::AID-BDM318>3.0.CO;2-F

- Tse, D. K., & Wilton, P. C. (1988). Models of consumer satisfaction formation: An extension. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378802500209

- Tukiran, M., Tan, P., & Sunaryo, W. (2021). Obtaining customer satisfaction by managing customer expectation, customer perceived quality and perceived value. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 9(2), 481–488. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.uscm.2021.1.003

- Van Ryzin, G. G. (2013). An experimental test of the expectancy-disconfirmation theory of citizen satisfaction. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(3), 597–614. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21702

- Voss, R., Gruber, T., & Szmigin, I. (2007). Service quality in higher education: The role of student expectations. Journal of Business Research, 60(9), 949–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.020

- Westbrook, R. A., & Oliver, R. L. (1991). The dimensionality of consumption emotion patterns and consumer satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(1), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1086/209243

- Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 177–195. https://doi.org/10.2307/20650284

- Wirtz, J., Mattila, A. S., & Tan, R. L. (2000). The moderating role of target-arousal on the impact of affect on satisfaction—an examination in the context of service experiences. Journal of Retailing, 76(3), 347–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00031-2

- Woodall, T., Hiller, A., & Resnick, S. (2014). Making sense of higher education: Students as consumers and the value of the university experience. Studies in Higher Education, 39(1), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.648373

- Yi, Y. (1990). A critical review of consumer satisfaction. Review of Marketing, 4(1), 68–123.

- Zeithaml, V. A., Ber ry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1993). The nature and determination of customer expectation of service. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070393211001

- Zhai, X., Gu, J., Liu, H., Liang, J. C., & Tsai, C. C. (2017). An experiential learning perspective on students’ satisfaction model in a flipped classroom context. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 198–210. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.20.1.198

- Zhao, Q., Wang, J. L., & Liu, S. H. (2021). A new type of remedial course for improving university students’ learning satisfaction and achievement. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2021.1948886