ABSTRACT

This paper explores the decision-making process of international non-EU postgraduates when choosing a qualification from a UK business school and proposes a new model which reflects the iterative, cyclical and continuous nature of the process. The degree of rigour and rationality employed in decision-making was often limited and influenced by culture and the composition of the decision-making unit (DMU). A Decision Maker Typology is proposed which will support segmentation strategies. Postgraduates continuously searched for information and relied on word of mouth information from students, parents, agents and academic staff. Online sources (websites, search engines and reviews) were perceived uncritically to be trustworthy sources. Data on reputation, rankings and friendship groups helped form choice sets. Forty-two qualitative interviews were conducted with international postgraduates from one Post-92 University. The need to meet the information requirements of all DMU members and stimulate information exchange to create a virtuous circle of communication was identified.

Introduction

The global market for international postgraduate students is becoming increasingly competitive as more Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) offer Masters level programmes to increase revenues. In 2020, 213,050 international non-EU postgraduates studied in UK HEIs which represented 33% of the postgraduate student population (HESA, Citation2021). The majority of them were studying taught qualifications in business and administrative studies (Chapman, Citation2019). International students generated £25.9 billion through on and off-campus spending by themselves and their visitors in 2019 (Universities, Citation2021). The UK Government and HEIs want to stop the declining trend in the market share of international students and have ambitious plans to increase their numbers to 600,000 students in the UK by 2030 to gain revenues of £35 billion helped by the new two-year post-study work visa (HM Government, Citation2021).

Little previous research in Higher Education has focused on international non-EU postgraduate students despite their complex decision-making process, distinct information needs and significance as a group to the market. Much of the previous research has used outdated linear decision-making models and has not recognised the importance of members of the DMU when choices are made between alternative countries, cities, universities and programmes (Branco Oliveira & Soares, Citation2016; Brown et al., Citation2009; Donaldson & McNicholas, Citation2004; Kotler & Keller, Citation1985; Moogan & Baron, Citation1999; Peralt-Rillo & Ribes-Giner, Citation2013; Vrontis et al., Citation2007). This qualitative study fulfils the need for up to date research that investigates individual postgraduates’ decision journeys and reflects changes in the use and perceived credibility of information sources in this digital age.

This paper aims to explore the decision-making cycle of international non-EU postgraduate students as they choose to study a UK business qualification and the role of other members in the decision-making unit (DMU). This study will help HEIs to support these students and DMU members and tailor their segmentation and targeting strategies to raise awareness of the institution and increase applications. This work addresses the following timely research questions:

What is the nature of international postgraduates’ decision-making process?

What sources of information and choice factors are evaluated?

What are the factors that impact on the rationality and rigour of the decision-making process?

What are the roles and information requirements of the members of the decision-making unit?

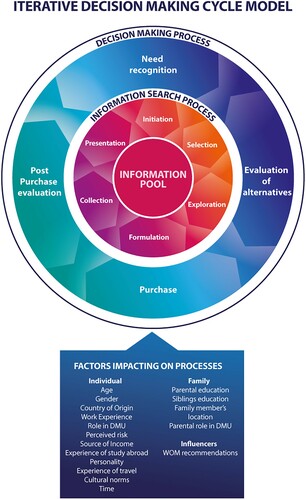

This paper reviews the literature, presents the methodology and findings and proposes a new Iterative Decision-making Cycle model and a Typology of Decision Makers which can be used to segment prospective postgraduates.

Literature review

The review of the literature focuses on the nature of the student decision-making process and factors impacting on it and the DMU.

Students’ decision-making process

Student decision-making was defined by Maringe (Citation2006, p. 468) as ‘a problem-solving process undertaken by applicants in the process of making choices’. A prospective international postgraduate student needed to make six decisions before studying at an overseas HEI; whether to study a postgraduate qualification, whether to study abroad, which country, institution and city to study in and which programme to choose (Pimpa, Citation2003a).

Postgraduate programmes, as an expensive service in terms of money and time, bought infrequently and involving intense and continuous contact between the postgraduate and the HEI, were classified as high involvement purchases (Kiley & Austin, Citation2014; Nicholls et al., Citation1995). As there were significant risks associated, postgraduates’ buying behaviour was classified as complex (Maringe & Carter, Citation2007). Theoretically high involvement, high-risk purchases involved extended decision-making processes and a rational approach whereby prospective postgraduates spent time at each stage of the process and cognitively processed the information gathered to reach an informed decision (Dibb et al., Citation2012). There was also rigour in the process as potential postgraduates carefully and thoroughly performed an extensive search for information and evaluated a number of alternatives by weighing up a variety of choice factors (Solomon et al., Citation2016).

In practice, researchers have found that the student decision-making process might not be extensive or rational (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, Citation2015). The current paper explores the rationality and rigour of the decision-making process by investigating the depth and breadth of the process.

The breadth of the decision-making process was assessed in this paper by exploring the size of prospective postgraduates’ choice set of universities that were considered and applied to, the number of sources of information processed and the variety of choice factors used. Towers and Towers (Citation2020) found that home and international postgraduates applied to between one and twenty universities with the average being three or four institutions. Choice sets were either wide and narrowed down or remained narrow without expansion.

The author investigated the depth of the process on the basis of the length of time it took for postgraduates to progress through each stage. The overall length of the process had varied between three months (Moogan & Baron, Citation2003), one year (Mellors-Bourne et al., Citation2014) and four years (Towers & Towers, Citation2020).

The sequence of decisions was also evaluated in this study. In Manns and Swift’s (Citation2016) research prospective, Chinese postgraduates decided firstly on the country to study in followed by the programme, then the university and finally the city. Industry research found that for the most part international students chose the subject or programme, followed by the country and lastly the university to study at (QS, Citation2019).

Models designed to explain the decision-making process of students as they chose where to study their university qualification started to emerge in the early 1980s. Chapman (Citation1986) was one of the first to look at buyer behaviour theory in relation to students and parents choosing an educational institution or programme. shows the most widely recognised model of the decision-making process (DMP) (Kotler & Keller, Citation2016; Schiffman & Kanuk, Citation2012) linked to other models of the consumer and students’ decision-making and choice processes. With the exception of Donaldson and McNicholas (Citation2004) and Peralt-Rillo and Ribes-Giner (Citation2013), the focus of the models was undergraduate and domestic students rather than international postgraduates.

Table 1. Consumer and student decision-making and choice models.

The models in assumed that students moved sequentially through the linear decision-making stages in a rational manner; recognising a need for postgraduate study, searching for information, evaluating alternatives, purchasing a qualification and then evaluating the purchase.

Some scholars have argued that older sequential, linear models of decision-making did not reflect the behaviour of individuals today, especially the Millennial generation brought up in the digital era, and that the consumer decision journey was continuous and cyclical (Court et al., Citation2009; Hudson & Hudson, Citation2013; Noble, Citation2010). Wolny and Charoensuksai (Citation2014) looked at three shopper journeys which were more circular than linear and emotionally based. Lemon and Verhoef (Citation2016) considered consumer touchpoints at each stage of their circular model.

Models were also developed that reflected the iterative nature of the decision-making process as consumers moved forwards and backwards without a planned or rational approach, made a number of decisions at the same time and revisited previous decisions (Hudson & Hudson, Citation2013).

Circular, iterative decision-making models to represent the postgraduate’s decision-making process were devised by industry specialists but these did not refer to information search or represent the complexities of today’s student-consumer decision-journey (HEFCE, Citation2014; Mellors-Bourne et al., Citation2014). Towers and Towers’ (Citation2020) circular postgraduate decision-making framework did however include information search as a separate stage and pre-search behaviour as impacting on the framework.

In the linear decision-making models, information search was considered to be a distinct, second stage when prospective postgraduates looked for information in order to decide on countries, cities, universities and programmes to choose. Some scholars have acknowledged that the search for information took place within other stages, but not throughout the process (Branco Oliveira & Soares, Citation2016; Court et al., Citation2009; Peralt-Rillo & Ribes-Giner, Citation2013). Appendix 1 shows the possible sources of information that prospective students could use when making their decisions based on mainly undergraduate studies. Only Moogan (Citation2020) and Manns and Swift (Citation2016) have focused specifically on international postgraduate students who made the decision to study in the UK.

In order to gain an in-depth insight into the affective, cognitive and physical dimensions of information search in this study, the author used Kuhlthau’s (Citation1993) Information Search Process model in the research. Kuhlthau’s model was chosen as it is highly regarded in many areas of information behaviour and recognises some of the complexities of postgraduates’ high-risk decision making (Wilson, Citation2004).

In the evaluation of alternatives stage of the linear models, postgraduates had an evoked set of university brands that were recommended, or that they were aware of, which they cut down to a shortlist or choice set of options to be evaluated (Schiffman & Kanuk, Citation2012). Postgraduates would decide on the factors of importance as listed in Appendix 2 and then weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of each university on the shortlist before purchasing a qualification (Solomon et al., Citation2016).

Once the prospective postgraduate had purchased a degree, they entered the post-purchase stage of the decision-making process and evaluated the educational service they had purchased. This led to a level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Solomon et al., Citation2013). This stage was considered to last from a few days (Maringe, Citation2006) to the first few weeks of attending a university (Nemar & Vrontis, Citation2016).

In seeking to develop a model that integrates both decision-making and information behaviour, the current research is contributing to evolving theory in both disciplines.

Factors impacting on the decision-making process

The factors that impacted on international students’ decision-making process are numerous as shown in .

Table 2. Factors impacting on international students’ decision-making process.

Previous studies shown in have focused on undergraduate students except for Towers and Towers’ (Citation2020) study of a mix of postgraduates from the UK and overseas. It has been acknowledged that the decision-making process of postgraduates, especially those who were international or working professionals, was impacted by alternative factors when compared to undergraduate and domestic students (Mellors-Bourne et al., Citation2014).

Culture was identified as influencing decision-making (Kotler & Keller, Citation2016). As participants in this study came from collectivistic cultures, as defined by Hofstede (Citation2001), such as Indonesia, Ghana, Bangladesh, China, Thailand, Vietnam, Kenya and Malaysia, there was the opportunity to explore the influence of collectivist cultural norms on decisions. Individuals from collectivist cultures have been described as committed to building strong relationships with a group and receiving loyalty from them in return (Hofstede Insights, Citation2021). Decisions, such as the decision to go to university, were often made collectively with the aim of helping the whole family rather than the individual. Prospective students, therefore, relied more on word of mouth (WOM) advice from others when choosing a university (Wilkins & Huisman, Citation2011).

Decision-making unit

In this study, the DMU or buying centre comprised those individuals who were involved in the purchase of the postgraduate qualification (Blythe, Citation2013). Webster and Wind (Citation1972) classified organisational decision-maker roles and these are related to an international student purchasing a postgraduate qualification in .

Table 3. DMU roles for postgraduate qualification purchase.

Zhu and Reeves (Citation2019, p. 1007) researched the decision to study a postgraduate qualification overseas amongst Chinese students and found that their parents influenced their decisions as they were making a ‘significant financial sacrifice’. Gatfield and Chen’s (Citation2006) study of Taiwanese postgraduates found their decisions might be influenced by WOM communication from friends and family. Moogan (Citation2020) referred to friends, family and agents as information sources and highlighted the role of personal recommendations from parents and partners when international postgraduates decided to study at a UK university.

There are gaps in the literature concerning the nature of international postgraduates’ decision-making process, the factors impacting on it including cultural norms, the information sources and choice factors evaluated, the composition of the DMU and the DMU’s information requirements, which are explored in this study (Miles, Citation2017).

Methodology

The research design was built on the results of a quantitative scoping study which was used as an exploratory framework to underpin design of the qualitative data collection instrument (Malhotra, Citation2020). The results presented draw on data from 42 qualitative interviews underpinned by an interpretivist philosophy (Creswell, Citation2018). These interviews were undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of postgraduates’ unique decision-making processes and build a new conceptual model (Silverman, Citation2020). International non-EU postgraduates from 15 countries, studying seven different business qualifications at a large Post-92 University in England, were interviewed on arrival and throughout the academic year up to graduation.

An experience-centred narrative interviewing style was used which encouraged the postgraduates to more openly discuss their experiences as they made the decision to study at the university (Bold, Citation2011). It also allowed the author to understand the chronological connections, sequencing and interpretation of decisions made and the factors impacting on their decisions (Andrews et al., Citation2008). A reflexive approach was adopted as the author gathered detailed information from participants while considering the interaction between herself as an academic and postgraduates as interviewees (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2017).

Semi-structured interviews were carried out as this gave the author the flexibility to ask the open-ended questions in the order that she deemed fit to encourage the participants’ narrative to flow freely, and to probe where appropriate (McIntosh & Morse, Citation2015). A pilot study of three interviews was used to test the interview guides. The interviews took place in the university meeting rooms and lasted from 25 min to 1 h. Participants agreed to the interviews being recorded and 20 h of interviews were transcribed and uploaded into NVivo version 12 software. Interviews were carried out from September 2018 to July 2019 until saturation occurred and there were no themes emerging (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). In order to ensure that the sample reflected the cohort of international non-EU postgraduates, non-probability purposive and volunteer sampling techniques were utilised. The author briefed classes of postgraduates on the research and the majority of participants volunteered to take part by signing a sheet (Saunders et al., Citation2016). The author then undertook purposive sampling to select participants who met certain criteria in terms of gender, programme studied and country of origin. These students were contacted by email and asked if they were willing to take part in the study (Easterby-Smith et al., Citation2015).

Both Thematic and Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) were undertaken. Thematic analysis highlighted patterns of meaning across the entire data set which enabled the elicitation of key themes which were common to the participants (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). An IPA approach allowed the exploration of each participant’s experiences and built a deeper understanding of how different perspectives and culture influenced them (Biggerstaff & Thompson, Citation2008).

Results and discussion

This section reports the qualitative findings from 42 interviews with 39 international non-EU postgraduates pertaining to the decision-making and information searching processes, decision-maker typology, factors impacting on the DMP and the DMU information requirements.

There were 18 male and 21 female participants aged from 22 to 39 years with 25 from Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia and Indonesia, three from Bangladesh and two from China and the USA. One postgraduate in each case came from India, Mauritius, Kenya, Ghana, Russia, Brazil and Syria. Sixty-nine per cent had studied previously in their home countries and 31% had studied overseas.

Decision-making process

When deciding to study at an overseas university, prospective international postgraduate students went through the need recognition, evaluation of alternatives and purchase stages of the decision-making process at varying speeds and levels of intensity.

The depth of the decision-making process was assessed by reference to the time period between need recognition and enrolment at university, ranging from two months to six years. The breadth of the decision-making process was measured by the number of UK universities that were evaluated by research participants in their choice sets, between one and 50 universities. Participants made an application to between one and nine universities with 16 students applying to one university and 14 applying to more than two universities.

Participants who did not have any knowledge of UK universities or WOM recommendations tended to have larger choice sets and evaluate more universities. Compared to previous research the time taken to make the decision was longer than typically found previously and there were a greater number of universities evaluated and applied to (Moogan & Baron, Citation2003; Towers & Towers, Citation2020).

The sequence of decisions for international postgraduates based on their experience and awareness of the university had not been previously explored. Participants with no prior experience or connection to the university decided on a country to study in, followed by the programme, then the university that best delivered that programme and finally the city, which agrees with Manns and Swift’s (Citation2016) study. Those participants who received a list of universities from agents would research universities and programmes simultaneously and then look at the cities before making their final choice. For participants who had prior experience of studying at partner universities, the city that the university was located in often determined their choice:

P11: I know from the [Thai University 1] they have the connection with [the University] and I searched about [the city] and I think it is a very nice city. That’s why I choose [the University].

Information search process

In this study, participants carried out information search continuously during the decision-making process, rather than being a distinct stage as previously identified (see ). It was conducted in an iterative manner. Participants moved backwards and forwards through the information search process stages in Kuhlthau’s (Citation1993) Information Search Process model; initiation, selection, exploration, formulation, collection and presentation, to revisit earlier sources.

The main motivations for participants to study a postgraduate qualification were to improve career prospects (n29), gain or update skills to become more employable (n5), enhance earnings (n5) or progress within a company (n5) as identified in the Postgraduate Taught Experience Survey (PTES) (Mellors-Bourne et al., Citation2016; Neves & Leman, Citation2019). Participants were also motivated to undertake postgraduate study to improve their English language capability (n3), gain cultural awareness and obtain the skills and knowledge required to return to their home countries and run their family business (n12) or set up their own business (n7). Entrepreneurial motivations were not previously identified in the literature.

The information sources used varied according to the decision-making process stages as shown in .

Table 4. Sources of information.

Parents, students, agents, friends and staff at partner institutions were used by participants as the most influential sources of information when choosing postgraduate study and specific universities (Manns & Swift, Citation2016). Such WOM sources were perceived to be more credible, impartial and less biased and, therefore, trusted by participants (Maringe & Carter, Citation2007; Moogan, Citation2020).

P24: But my friends said [the University] is for me, it’s suitable for me and so that is why I come here.

University and ranking websites, Google searches and online reviews were frequently used by participants when creating long lists and shortlists of universities, making choices and in the post-purchase stage which agrees with previous studies (Moogan, Citation2020; Towers & Towers, Citation2020). Online sources were perceived to have credibility regardless of their origins or authority.

P39: … I really like what it said on the website so I decided to choose [the University] and apply.

Contrary to the literature, social media and email were not important information sources (Hobsons, Citation2017; Rekhter & Hossler, Citation2019; Royo-Vela & Hünermund, Citation2016). Offline sources such as the prospectus, fairs, and visits were rarely used (Renfrew et al., Citation2010). Participants progressed through to application before they contacted a university representative to seek advice and many made their final decision without ever contacting the university by relying on online and WOM sources of information. Participants felt uncertain during and after the application process prior to attending the university and would have welcomed university communications at this time.

Iterative and cyclical decision-making

Participants progressed through the stages of the decision-making process in an iterative manner. During the evaluation of alternatives stage, they made decisions concerning the country, city, university and programme, separately or simultaneously, and then went back and appraised those decisions. Participants would form a shortlist of certain universities from a longer list and then some would add new universities to their shortlist. Similarly, they applied to a number of universities in the purchase stage and then yet still revisited the evaluation of alternatives stage to investigate new universities. Post-purchase participants would return to decisions made in previous stages to reassure themselves that they had made the right decisions.

The decision-making process was cyclical and continuous in nature as participants learnt from their approach to making the high involvement decision which then informed how they would approach subsequent decisions. Those who were satisfied that they had made the right decision based on a rigorous and rational evaluation of alternative options stated that they would repeat the same process again.

Other participants were dissatisfied with the decision they had made and would approach future high involvement decisions differently by evaluating additional alternative options more critically and giving themselves time to make a considered decision:

One participant had already studied a postgraduate qualification and simplified the decision-making process on a subsequent choice of a programme by evaluating nine rather than fifty universities:

P9: I had learned from my first decision with [C University] so I made the decision with [the University] more simply with a smaller number of universities.

Choice factors

Participants evaluated a number of choice factors when making the decision to study in the UK, in a certain city, university and programme as shown in .

Table 5. Choice factors.

The reputation and quality of the education system was the most important choice factor when choosing the UK as a study destination:

P21: The UK has one of the finest education systems in the world […] It was the quality of education that motivated me to want to come here.

Participants also chose the UK for its shorter one-year degree compared to other countries, and the recognition of UK qualifications amongst employers, which increased the likelihood of job-hunting success (Manns & Swift, Citation2016).

Most previous studies focused on the choice factors of importance when deciding on a university and a city at the same time, whereas Cubillo et al.’s (Citation2006) reported a separate city image stage. The factors of importance when choosing a city were; location close to London, near the coast and tourist destinations; reputation as a peaceful, clean, not crowded, safe city with friendly people; and presence of an ethnic population that could provide support.

When deciding on universities, the modules offered on the programme often became the point of differentiation along with rankings and reputation (Hemsley-Brown, Citation2012). The university’s reputation amongst employers in the home country and overseas was a key choice factor. Reputation was built up over time through a virtuous circle of communication as alumni from the university obtained jobs, communicated the benefits of studying at the institution to potential postgraduates who after studying were then recruited by the alumni. These postgraduates then recommended the university to others and the virtuous circle of communication continued which increasingly benefited the university, postgraduates and employers.

When choosing a university this study highlighted the importance to postgraduates, especially those from collectivist cultures, of a community of students from their home country from which to obtain support and friendship groups. Those participants who had studied the university’s qualifications in their home countries or the UK were more likely to choose the university for the same reasons.

The ease of the application process and the speed of the offer was an influential choice factor. Participants wanted to minimise the number of applications made and would take a shortcut to purchase when they received the first offer, ignoring other universities in their choice sets.

Typology of decision-makers

A Typology of Decision Makers was developed which categorised participants based on their level of awareness of the university as new, connected, experienced or local. The extent to which participants performed a rigorous search and evaluation of information and approached the decision-making process in a rational manner was reflected in the categories; systematic, semi systematic, limited or shortcut, as shown in .

Table 6. Typology of decision maker.

Decision-maker types ranged from ‘New Systematic’ postgraduates who were the least aware of the University and had the most rational and rigorous approach, through ‘Semi systematic’ to ‘Experienced Limited’ postgraduates who had studied the University’s programmes and often did not perform a systematic search or spend time contemplating their decision.

There were those postgraduates who were classified as ‘Shortcut’ because they made the final decision unduly quickly due to a gut feeling or one specific piece of information often from a WOM source.

P34: Actually they are the main reason I come here because I just ask my friend who had just graduated from here “How was it?” and it make me decide to come here.

Overall, there was a lack of rationality and information used when making this potentially high involvement decision. Less than half of the sample (n14) approached the decision with a ‘systematic’ approach and spent time at each stage. However, six of these participants then took a shortcut to the final decision, based on emotional rather than rational criteria.

P27: I have not know as much information as I wanted to know. But someone said [the University] is good […] good living, good for studying, so I came.

The remaining participants (n17) had less rigorous and rational ‘semi systematic’ (n9) or ‘limited’ (n8) approaches. Within the group of ‘New’ postgraduates, there were four participants who had taken a ‘semi systematic’ approach and admitted that their level of informedness was low. Those participants whose approach was ‘limited’ were either ‘Connected’ (n4), ‘Experienced’ (n3) or ‘Local’ (n1) prospective postgraduates. This group relied more heavily on WOM recommendations:

P33: So they [friends] tell me the information about [the University] and I decided to come here [ … ] I haven’t looked at any others. Just [the University] as I have friends to come with.

‘Semi systematic’ or ‘limited’ postgraduates were the most likely to question whether they had made the right decision. They reflected that they would approach high involvement decisions in the future with more rigour and greater rationality.

Factors impacting on the decision-making process

The degree of rigour and rationality with which participants approached the decision-making and information search processes depended on the factors shown in .

Table 7. Factors impacting on the decision-making and information search processes.

Cultural norms influenced the processes. Those from collectivist cultures, such as Thailand and Vietnam, were more heavily influenced by WOM sources, curtailed their information searches and made their decisions more quickly.

P33: Yes she [friend] decided to come here so I followed her.

An Indian participant had a more fatalistic attitude to making a decision and used emotional rather than rational criteria, taking a shortcut to the final purchase.

P9: I am coming to that university just because of the physicality and the beauty the university had […] that was the first university I ever saw […] they accepted me with open arms, so that’s all I should want from a university.

Age, gender and work experience were also influential. Older postgraduates, females and those with work experience performed comprehensive information searches and spent more time making the final decision in a rational manner compared to younger postgraduates, males and those who had not been employed.

The composition of the DMU and the background and roles of its members also impacted on the approach to the decision-making process. If the postgraduate made a decision with no or little support from DMU members, their approach was more systematic and rational. The educational and travel experiences of the participants’ parents and other family members influenced the degree to which participants needed to search for missing information and the extent to which they were given the freedom to make an emotionally based choice.

The source of finance for the purchase and personality traits linked to adaptability and resilience, impacted on the degree of risk participants perceived in the process of making the decision. Prior experience of the service, of travelling, living or studying abroad, reduced the level of perceived risk. The higher the perceived risk the more rigorous and systematic was the decision-making process and the more informed participants were when making their final decision.

Decision-making unit information requirements

Participants were asked to report on information that the DMU members provided to them and the information which DMU members asked them to obtain. From this, the information needs of DMU members were inferred and the composition of the DMU was determined. There were between one and six members of the DMU (average 4.2 members) when participants decided which country, city, university and programme to choose as shown in .

Table 8. DMU member roles.

Parents acted as initiators triggering a need for postgraduate study, deciders who helped participants to choose the final programme to purchase and the buyers who paid for the postgraduate qualification. Parents had a much more significant role in the decision-making process than identified in previous literature regardless of whether or not postgraduates came from collectivist cultures (Zhu & Reeves, Citation2019). The more significant the parental role the less rigorous and systematic were participants’ decision-making processes.

P11: I asked my parents because my parents have known me for so long. They know which one is the best for me.

Friends, who were current students or alumni, played an important role as influencers in the DMU providing information on the ‘real experience’ and lifestyle when studying at institutions and triggering the need for postgraduate study.

Agents and partner university staff acted as gatekeepers in the DMU. They provided lists of universities to investigate and these lists often formed the complete choice set of universities that were considered.

P28: I contacted the agency and I showed them my grades and my experience and all that and then they gave me a list of universities for me to choose from.

They built relationships with participants over time as they got to know their needs and became trusted sources of information on all aspects of the university.

Participants regarded academic staff in the partner or previous institution as a credible and trustworthy source of information and their choice set and final decision as to which university to attend were often based on their advice.

shows the types of information which the most important DMU members provided to prospective postgraduates from which their information requirements could be inferred.

Table 9. DMU information provision.

Conclusions

The Iterative Decision-making Cycle Model in is proposed by the author based on theoretical models from marketing scholars (Kotler & Keller, Citation2016; Solomon et al., Citation2016) and Kuhlthau on information behaviour. The model represents the postgraduates’ decision-making and information search processes from recognition of the need to study a Masters qualification to graduation. Considering the post-purchase evaluation stage as lasting throughout postgraduates’ time at university has not been proposed in previous models.

Previous sequential and linear decision-making models assumed that the decision-making process for a high involvement product was planned and rational and that students made one decision after another in a sequential fashion. This circular and iterative model reflects the findings from this study that some postgraduates approached the decision-making and information search processes in a systematic and rational manner while others proceeded with less rigour, took shortcuts and made decisions based on emotional criteria. Postgraduates were found to make multiple decisions at the same time in terms of the country, city, university and programme. They would move backwards and forwards through the stages of the decision-making cycle and revisit previous decisions, choice factors and information sources. The model is cyclical because postgraduates learnt from the decisions they made, and their experiences influenced how they would approach decision-making and information search in the future, in a continuous manner.

Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process is depicted in the inner ring as informing all the stages of the decision-making process. The information pool at the centre of the model reflects the interconnectedness of individuals in this digital era. A virtuous cycle of WOM communication was in evidence as postgraduates and other DMU members gathered information from the pool of information and then contributed to the pool to help other members make their decisions. The pool was especially important to those from collectivist cultures who relied on WOM recommendations. The box at the bottom of the model lists the factors that are pictured as impacting on the degree of rigour and rationality of the decision-making and information search processes.

This study contributes to the body of knowledge in marketing as it helps individuals to understand the cyclical and iterative nature of the decision-making cycle, the breadth and depth of the process and the sequence of decisions made by different groups of postgraduates. Online sources including the university website, rankings, internet search engines and reviews were found to be increasingly important and credible regardless of their origins or authority. Reputation, rankings and the possibility of friendship groups were key choice factors used to decide on universities, especially for those without WOM recommendations.

Despite living in an information-rich world there was a lack of rationality and informedness amongst certain groups of postgraduates when making this high involvement decision and tailored information to ‘new’, ‘experienced’ and ‘connected’ prospective postgraduates, as identified in the Decision Maker Typology in , should reflect this.

There is a need to communicate pertinent information to parents, friends, students, alumni, agents and academic staff as important target audiences. Parents wanted information regarding the safety and fulfilment of their children during and after their Masters. Friends and students provided information to reassure prospective postgraduates that they would be able to cope with the demands of academic study, successfully complete their degrees and have a positive university experience. Agents and academic staff suggested lists of universities to apply to, reassured potential postgraduates and supported them in their applications. Universities should try and stimulate information exchange amongst DMU members to create a virtuous circle of communication.

Communications to raise awareness of universities could be managed so that the different segments identified in the Typology and amongst the DMU members are targeted by specialists who understand their information needs. Personalised communications messages and media could be prepared and then delivered to specific segments as needed.

This study makes a practical contribution. The model is of practical value to HEI marketers who can gain a competitive advantage due to a greater understanding of the postgraduates’ decision-making process and the cultural and other factors that influence the process. The Typology of Decision Makers provides a framework for HEIs segmentation and targeting strategies.

Limitations and future research

This study focused on international non-EU postgraduates from one institution which might not represent all student views. Future research could include European and UK postgraduates in different universities in the UK studying different courses. International postgraduates from other countries and those studying in overseas universities could also be studied to obtain a broader insight into the impact of different cultures on the decision-making cycle of postgraduates and further test the model and the typology. The role of DMU members as information providers and their information requirements could also be further explored.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abubakar, B., Shanka, T., & Muuka, G. N. (2010) Tertiary education: An investigation of location selection criteria and preferences by international students – The case of two Australian universities. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 20(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241003788052

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2017). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research. Sage.

- Andrews, M., Squire, C., & Tamboukou, M. (2008). Doing narrative research. Sage.

- Belanger, C. H., Bali, S., & Longden, B. (2014). How Canadian universities use social media to brand themselves. Tertiary Education and Management, 20(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2013.852237

- Biggerstaff, D., & Thompson, A. R. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): A qualitative methodology of choice in healthcare research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 5(3), 214–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14780880802314304

- Binsardi, A., & Ekwulugo, F. (2003). International marketing of British education: Research on the students’ perception and the UK Market penetration. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 21(5), 318–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500310490265

- Blackwell, R. D., Miniard, P. W., & Engel, J. F. (2001). Consumer behavior. South Western.

- Blythe, J. (2006). Essentials of marketing. Pearson Education.

- Blythe, J. (2013). Consumer behaviour. Sage.

- Bodycott, P. (2009). Choosing a higher education study abroad destination: What mainland Chinese parents and students rate as important. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(3), 349–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240909345818

- Bold, C. (2011). Using narrative in research. Sage.

- Bonnema, J., & Van der Waldt, D. L. R. (2008). Information and source preferences of a student Market in Higher education. International Journal of Educational Management, 22(4), 314–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540810875653

- Branco Oliveira, D., & Soares, A. M. (2016). Studying abroad: Developing a model for the decision process of international students. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 38(2), 126–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2016.1150234

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Briggs, S., & Wilson, A. (2007). Which university? A study of the influence of cost and information factors on Scottish undergraduate choice. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 29(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800601175789

- Brown, C., Varley, P., & Pal, J. (2009). University course selection and services marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 27(3), 310–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500910955227

- Calikoglu, A. (2018). International student experiences in non-native-English-speaking countries: Postgraduate motivations and realities from Finland. Research in Comparative and International Education, 13(3), 439–456. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499918791362.

- Callender, C., & Jackson, J. (2008). Does the fear of debt constrain choice of university and subject of study? Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 405–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802211802

- Chapman, R. G. (1986). Toward a theory of college selection: A model of college search and choice behavior. In R. J. Lutz (Ed.), NA-advances in consumer research 13 (pp. 246–250). Association for Consumer Research.

- Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS). (2019). Analysis of postgraduate qualifications in business & administrative studies. CABS. https://charteredabs.org/publications/analysis-of-postgraduate-qualifications-in-business-administrative-studies/

- Chen, L.-H. (2007). Choosing Canadian graduate schools from afar: East Asian students’ perspectives. Higher Education, 54(5), 759–780. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9022-8

- Chen, L.-H. (2008). Internationalization or international marketing? Two frameworks for understanding international students’ choice of Canadian universities. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 18(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841240802100113

- Chung, K. C., Holdsworth, D. K., Li, Y., & Fam, K. S. (2009). Chinese ‘Little emperor’: Cultural values and preferred communication sources for university choice. Young Consumers, 10(2), 120–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17473610910964705

- Clark, M. (2007). The impact of higher education rankings on student access, choice, and opportunity. Journal of Higher Education in Europe, 32(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720701618880

- Court, D., Elzinga, D., Mulder, S., & Vetvik, O. (2009). The consumer decision journey. McKinsey Quarterly.

- Cremonini, L., Westerheijden, D., & Enders, J. (2008). Disseminating the right information to the right audience: Cultural determinants in the use (and misuse) of rankings. Higher Education, 55(3), 373–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9062-8

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed Methods approaches. Sage.

- Cubillo, J. M., Sanchez, J., & Cervino, J. (2006). International students’ decision-Making process. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(2), 101–115. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540610646091

- de Jager, J., & du Plooy, T. (2010). Information sources used to select a higher education institution: Evidence from South African students. Business Education & Administration, 2(1), 61–75.

- Diamond, A., Evans, J., Sheen, J., & Birkin, G. (2015). UK review of information about higher education: information mapping study: Report to the UK higher education funding bodies.” HEFCE. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk//24490/

- Dibb, S., Simkin, L., Pride, W., & Ferrell, O. (2012). Marketing concepts and strategies. Houghton Mifflin.

- Donaldson, B., & McNicholas, C. (2004). Understanding the postgraduate education market for UK-based students: A review and empirical study. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 9(4), 346–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.259

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. R. (2015). Management and business research. Sage.

- Foster, M. (2014). Student Destination choices in Higher Education: Exploring attitudes of Brazilian students to study in the United Kingdom. Journal of Research in International Education, 13(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240914541024

- Galan, M., Lawley, M., & Clements, M. (2015). Social media's use in postgraduate students’ decision-making journey: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 287–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1083512

- Gatfield, T., & Chen, C. H. (2006). Measuring student choice criteria using the theory of planned behaviour: The case of Taiwan, Australia, UK, and USA. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 16(1), 77–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v16n01_04

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldire.

- Goff, B., Patino, V., & Jackson, G. (2004). Preferred information sources of high school students for community colleges and universities. Community College Journal of Research & Practice, 28(10), 795–803. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920390276957

- Gomes, L., & Murphy, J. (2003). An exploratory study of marketing international education online. International Journal of Educational Management, 17(3), 116–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540310467787

- Gong, X., & Huybers, T. (2015). Chinese students and higher education destinations: Findings from a choice experiment. Australian Journal of Education, 59(2), 196–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944115584482

- Hagedorn, L. S., & Zhang, Y. (2011). The use of agents in recruiting Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Studies in International Education, 15(2), 186–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315310385460

- Hanson, K., & Litten, L. (1982). Mapping the road to academia: A review of research on women, men, and the college selection process. Review of Higher Education, 19, 179–198.

- Hazelkorn, E. (2015). Effect of rankings on student choice and institutional selection. In Access and expansion post-massification (pp. 125–146). Routledge.

- Hemsley-Brown, J. (2012). The best education in the world’: Reality, repetition or cliché? International students’ reasons for choosing an English university. Studies in Higher Education, 37(8), 1005–1022. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.562286

- Hemsley-Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2015). Higher education consumer choice. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). (2014). Guidance on providing information for prospective taught postgraduate. Annex A. HEFCE. https://www.hefcw.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/W14-15HE-Guidance-on-providing-information-for-prospective-taught-postgraduate-Annex-A.pdf

- Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). (2021). Institution level data. HESA. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students

- HM Government. (2021). International Education Strategy: 2021 update. Department for Education and Department for International Trade. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/958990/International-Education-Strategy-_2021-Update.pdf

- Hobsons. (2017). International student survey 2017. The changing dynamics of international student recruitment. Hobsons.

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage.

- Hofstede Insights. (2021). Hofstede Insights. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/

- Hossler, D., & Gallagher, K. S. (1987). Studying student college choice: A three-phase model and the implications for policymakers. College and University, 62(3), 207–221.

- Hudson, S., & Hudson, R. (2013). Engaging with consumers using social media: A case study of music festivals. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 4(3), 206–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-06-2013-0012

- Imenda, S. N., Kongolo, M., & Grewal, A. S. (2004). Factors underlying technikon and university enrolment trends in South Africa. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 32(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143204041884

- Jackson, G. A. (1982). Public efficiency and private choice in higher education. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 4(2), 237–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737004002237

- James-MacEachern, M., & Yun, D. (2017). Exploring factors influencing international students’ decision to choose a higher education institution: A comparison between Chinese and other students. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(3), 343–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2015-0158

- Jepsen, D. M., & Varhegyi, M. M. (2011). Awareness, knowledge and intentions for postgraduate study. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 33(6), 605–617. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2011.621187

- Joseph, M., & Joseph, B. (2000). Indonesian students’ perceptions of choice criteria in the selection of a tertiary institution: Strategic implications. International Journal of Educational Management, 14(1), 40–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540010310396

- Khanna, M., Jacob, I., & Yadav, N. (2014). Identifying and analyzing touchpoints for building a higher education brand. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 24(1), 122–143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2014.920460

- Kiley, M., & Austin, A. (2000). Australian postgraduate students’ perceptions, preferences and mobility. Higher Education Research & Development, 19(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360050020480

- Kondakci, Y. (2011). Student mobility reviewed: Attraction and satisfaction of international students in Turkey. Higher Education, 62(5), 573–592. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9406-2

- Kotler, P., & Fox, K. (1985). Strategic marketing for educational institutions. Prentice Hall.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2016). Marketing management. Pearson.

- Krezel, J., & Krezel, Z. A. (2017). Social influence and student choice of higher education institution. Journal of Education Culture and Society, 7(2), 116–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15503/jecs20172.116.130

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (1993). A principle of uncertainty for information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 49(4), 339–355. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/eb026918

- Lee, J. J., & Sehoole, C. (2015). Regional, continental, and global mobility to an emerging economy: The case of South Africa. Higher Education, 70(5), 827–843. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9869-7

- Lemon, K., & Verhoef, P. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0420

- Leng, H. K. (2012). The use of Facebook as a marketing tool by private educational institutions in Singapore. International Journal of Technology and Educational Marketing (IJTEM), 2(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/ijtem.2012010102

- Liu, J. (2010). The changing Body of students: A study of the motives, expectations and preparedness of postgraduate marketing students. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(7), 812–830. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501011086436

- Malhotra, N. K. (2020). Marketing research: An applied orientation. Pearson Education.

- Manns, Y., & Swift, J. (2016). Chinese postgraduate choices when considering a UK business and management programme. Higher Education Quarterly, 70(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12080

- Maringe, F. (2006). University and course choice: Implications for positioning, recruitment and marketing. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(6), 466–479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540610683711

- Maringe, F., & Carter, S. (2007). ‘International Students’ motivations for studying in UK HE: Insights into the choice and decision making of African students. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(6), 459–475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540710780000

- Mazzarol, T., & Soutar, G. N. (2002). ‘Push-pull’ factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 82–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540210418403

- McIntosh, M. J., & Morse, J. M. (2015). Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615597674

- McMahon, M. E. (1992). Higher education in a world market. Higher Education, 24(4), 465–482. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00137243

- Mellors-Bourne, R., Hooley, T., & Marriott, J. (2014). Understanding how people choose to pursue taught postgraduate study. The Careers Research and Advisory Centre (CRAC) and the University of Derby International Centre for Guidance Studies (iCeGS). HEFCE. https://www.crac.org.uk/portfolio/research/educational-progression-transitions-and-outcomes/understanding-how-people-choose-to-pursue-taught-postgraduate-study-hefce-2014-2

- Mellors-Bourne, R., Mountford-Zimdars, A., Wakeling, P., Rattray, J., & Land, R. (2016). Postgraduate transitions: Exploring disciplinary practice. Higher Education Academy. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/postgraduate-transitions-exploring-disciplinary-practice

- Miles, D. A. (2017). A taxonomy of research gaps: Identifying and defining the seven research gaps. In Doctoral student workshop: Finding research gaps-research methods and strategies (pp. 1–15).

- Moogan, Y. J. (2020). An investigation into international postgraduate students’ decision-making process. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1513127

- Moogan, Y. J., & Baron, S. (2003). An analysis of student characteristics within the student decision making process. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27(3), 271–287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877032000098699

- Moogan, Y. J., Baron, S., & Harris, K. (1999). Decision-making behaviour of potential higher education students. Higher Education Quarterly, 53(3), 211–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2273.00127

- Nemar, S. E., & Vrontis, D. (2016). A higher education student-choice analysis: The case of Lebanon. World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development, 12(2-3), 337–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/WREMSD.2016.074973

- Neves, J., & Leman, J. (2019). Postgraduate taught experience survey 2019. Advance HE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/PTES-2019

- Nicholls, J., Harris, J., Morgan, E., Clarke, K., & Sims, D. (1995). Marketing higher education: The MBA experience. International Journal of Educational Management, 9(2), 31–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513549510082369

- Nicholls, S. (2018). Influences on international student choice of study destination: Evidence from the United States. Journal of International Students, 8(2), 597–622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v8i2.94

- Noble, S. (2010). It’s time to bury the marketing funnel. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/2010/12/08/customer-life-cycle-leadership-cmo-network-funnel.html

- Obermeit, K. (2012). Students’ choice of universities in Germany: Structure, factors and information sources used. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 22(2), 206–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2012.737870

- Peralt-Rillo, A., & Ribes-Giner, G. (2013). A proactive market orientation for the postgraduate programs. Dirección y Organización, 50(50), 37–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.37610/dyo.v0i50.430

- Pimpa, N. (2003a). Development of an instrument for measuring familial influence on Thai students’ choices of international education. International Education Journal, 4(1), 24–29.

- Pimpa, N. (2003b). The influence of peers and student recruitment agencies on Thai students’ choices of international education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 7(2), 178–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315303007002005

- Pyvis, D., & Chapman, A. (2007). Why university students choose an international education: A case study in Malaysia. International Journal of Educational Development, 27(2), 235–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2006.07.008

- QS. (2019). International student survey: Growing global education. Rising to the international recruitment challenge. http://info.qs.com/rs/335-VIN-535/images/QS_ISS19_UK.pdf

- Rekhter, N., & Hossler, D. (2019). Place, prestige, price, and promotion: How international students use social networks to learn about universities abroad. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 8(1), 124–145.

- Renfrew, K., Baird, H., Green, H., Davies, P., Hughes, A., Mangan, J., & Slack, K. (2010). Understanding the information needs of users of public information about higher education. HEFCE by Oakleigh Consulting and Staffordshire University. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/1994/1/rd12_10b.pdf

- Royo-Vela, M., & Hünermund, U. (2016). Effects of inbound marketing communications on HEIs’ brand equity: The mediating role of the student’s decision-making process: An exploratory research. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(2), 143–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2016.1233165

- Rudd, B., Djafarova, E., & Waring, T. (2012). Chinese students’ decision-making process: A case of a business school in the UK. The International Journal of Management Education, 10(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2012.04.001

- Saiti, A., Papa, R., & Brown, R. (2017). Postgraduate students’ factors on program choice and expectation. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 9(3), 407–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-06-2016-0040

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2016). Research methods for business students (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Schiffman, L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (2012). Consumer behaviour. Pearson.

- Shanka, T., Quintal, V., & Taylor, R. (2006). Factors influencing international students’ choice of an education destination: A correspondence analysis. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 15(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v15n02_02

- Silverman, D. (2020). Qualitative research. Sage.

- Simões, C., & Soares, A. M. (2010). Applying to higher education: Information sources and choice factors. Studies in Higher Education, 35(4), 371–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903096490

- Singh, M. K. M. (2016). Socio-Economic, environmental and personal factors in the choice of country and higher education institution for studying abroad among international students in Malaysia. International Journal of Educational Management, 30(4), 505–519. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2014-0158

- Slack, K., Mangan, J., Hughes, A., & Davies, P. (2014). ‘Hot’, ‘cold’ and ‘warm’ information and higher education decision-making. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 35(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2012.741803

- Sojkin, B., Bartkowiak, P., & Skuza, A. (2012). Determinants of higher education choices and student satisfaction: The case of Poland. Higher Education, 63(5), 565–581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9459-2

- Solomon, M., Bamossy, G., & Askegaard, S. (2013). Consumer behaviour: A European perspective. Prentice Hall.

- Solomon, M., Bamossy, G., Askegaard, S., & Hogg, M. (2016). Consumer behaviour: A European perspective. Pearson Education.

- Souto-Otero, M., & Enders, J. (2017). International students’ and employers’ use of rankings: A cross-national analysis. Studies in Higher Education, 42(4), 783–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1074672

- Teng, S., & Khong, K. W. (2015). An exploratory investigation of study-abroad online information cues. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 26(3), 177–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08975930.2015.1078268

- Towers, A., & Towers, N. (2020). Re-evaluating the postgraduate students’ course selection decision making process in the digital Era. Studies in Higher Education, 45(6), 1133–1148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1545757

- Universities, U. K. (2021). The costs and benefits of international higher education students to the UK economy. London Economics. HEPI. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Summary-Report.pdf

- Veloutsou, C., Paton, R. A., & Lewis, J. (2005). Consultation and reliability of information sources pertaining to university selection: Some questions answered? International Journal of Educational Management, 19(4), 279–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540510599617

- Vrontis, D., Thrassou, A., & Melanthiou, Y. (2007). A contemporary higher education student-choice model for developed countries. Journal of Business Research, 60(9), 979–989. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.01.023

- Webster, F. E., & Wind, Y. (1972). A general model for understanding organizational buying behavior. Journal of Marketing, 36(2), 12–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297203600204

- Wiers-Jenssen, J. (2019). Paradoxical attraction? Why an increasing number of international students choose Norway. Journal of Studies in International Education, 23(2), 281–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318786449

- Wiese, M., Jordaan, Y., & Van Heerden, C. H. (2010). Differences in the usefulness of communication channels, as experienced by gender and ethnic groups during their university selection process. Communication: South African Journal for Communication Theory and Research, 36(1), 112–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02500160903525064

- Wilkins, S., & Huisman, J. (2011). International student destination choice: The influence of home campus experience on the decision to consider branch campuses. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 21(1), 61–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2011.573592

- Williams, R., & Van Dyke, N. (2008). Reputation and reality: Ranking major disciplines in Australian universities. Higher Education, 56(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9086-0

- Wilson, T. D. (2004). Review of: Kuhlthau, C.C. “seeking meaning: A process approach to library and information services”. 2nd Ed. Libraries Unlimited. Information Research, 9 (3), review no. R129 http://informationr.net/ir/reviews/revs129.html

- Wolny, J., & Charoensuksai, N. (2014). Mapping customer journeys in multichannel decision-making. Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice, 15(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/dddmp.2014.24

- Wu, Q. (2014). Motivations and decision-making processes of mainland Chinese students for undertaking master’s programs abroad. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(5), 426–444. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313519823

- Yang, H.-P., & Mutum, D. S. (2015). Electronic word-of-mouth for university selection: Implications for academic leaders and recruitment managers. Journal of General Management, 40(4), 23–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/030630701504000403

- Zhou, J. (2015). International students’ motivation to pursue and complete a Ph. D. In the US. Higher Education, 69(5), 719–733. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9802-5

- Zhu, L., & Reeves, P. (2019). Chinese students’ decisions to undertake postgraduate study overseas. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(5), 999–1011. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2017-0339