ABSTRACT

This paper investigates influences on the decision-making process, during the consideration of applying to university, for UK further education college students from a widening participation background (Uni Connect). Much previous research has explored the international student recruitment market, however, there is relatively little literature concerning UK home student recruitment, particularly related to widening participation groups. Three semi-structured interviews were conducted with eight, second-year, level 3 vocational students, during their final year of college study. Findings suggest that Uni Connect students seek multiple sources of information and engage with a multitude of touch points, with the context of these interactions playing a significant role in influencing university choice. The exhibition of predominately rational rather than emotive behaviours and the use of multiple touch points, suggests that Uni Connect students take an iterative approach to their decision-making. The decision-making process appears to be individualised, with no equivocal or homogenic pattern emerging.

Introduction

The past twenty years have seen a global movement towards expanding student choice relating to higher education (HE) options and the increased impact that external forces can have on the decisions of college students with regard to any HE destination (Chun Sing Ho & Lu, Citation2019). Following the marketisation of HE and the move to a ‘student choice’ model of public service funding (Le Grand, Citation2010), students are no longer passive consumers when it comes to the selection of university degrees and the institutions themselves (Maringe, Citation2006). Given that Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are looking to compete for student numbers, significant emphasis is placed on university recruitment teams to increase recruitment for establishments. An integral component in this quest to recruit more students is the experience of the potential applicant during the application period. This experience will influence their decision-making process and is key in determining which university and subsequent course they will enrol in (McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022). As education is a service and not a product, it cannot be significantly sampled in advance or tested before the choice is made to enrol into a programme (Khanna et al., Citation2014). Therefore, the applicant’s experience during the pre-admissions and admissions process will have an impact on their affinity to a particular institution and/ or course, thus significantly influencing their decision-making process (Dirin et al., Citation2021; Gai et al., Citation2016; Galan et al., Citation2015; Khanna et al., Citation2014; Towers & Towers, Citation2020).

As Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka (Citation2015) postulate that higher education isn’t a homogenous market place and thus it is difficult to establish distinct reasons as to why particular students will pick a university, this study will look to explore the decision-making experiences during the application phase of applying to university, of Uni Connect (UC) individuals. Uni Connect individuals, as defined by the Office for Students (OfS), are from areas and wards within England, where engagement with and progression to Higher Education, is low (Office for Students, Citationn.d.). This research was funded by the Southern Universities Network (SUN) as part of the UC programme (funded by the OfS).

Much previous research has explored the lucrative international student recruitment market and the decision-making processes of potential students in this landscape (Dowling-Hetherington, Citation2020; McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022; Moogan, Citation2020; Rafi, Citation2018; Rembielak et al., Citation2020; Royo-Vela & Hünermund, Citation2016). However, there is relatively little literature which has explored UK home student recruitment, particularly that related to the widening participation agenda and individuals and groups encompassed by this. Research by Heathcote et al. (Citation2020) shows that a singular model or framework cannot necessarily be applied to diverse groups when it comes to decision-making behaviours related to choosing an HEI at which to study. When comparing research into international student decision-making (Dowling-Hetherington, Citation2020; Rafi, Citation2018; Rembielak et al., Citation2020), UK home student decision-making (Bennett & Ali-Choudhury, Citation2009; Callender & Melis, Citation2022; Winter & Thompson-Whiteside, Citation2017) and postgraduate decision-making (McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022; Moogan, Citation2020) – as an example of the many different permutations of groups and contextual backgrounds of applicants – we see that different groups exhibit differing decision-making behaviours and have different preferences depending on their context. Therefore, the lack of research into UC groups means that applying frameworks and models related to other demographic groups, to predict the behaviours and processes of widening participation applicants, is hazardous and potentially erroneous. With over 1 million young people classified as Uni Connect since 2017 (Office for Students, Citationn.d.), this lack of understanding of their decision-making processes may significantly hinder the effectiveness of recruitment and outreach teams to engage with a large population of prospective applicants.

Within this exploration of UC student decision-making processes and what influences them when contemplating post-college choices, particular focus will be placed on their relationship with specific touch points. Previous studies suggest that touch points such as teachers, friends, digital media and college-based advisors have an influence on the decision-making process of university applicants (Dirin et al., Citation2021; McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022; Moogan, Citation2020; Royo-Vela & Hünermund, Citation2016). The purpose of this study was to establish if this is the case for UC students, and seeks to clarify the internal and external factors that affect and influence this decision-making process. Although specific to the UK widening participation environment, the findings of this study contribute to the overall understanding of HE applicant decision-making processes and behaviours and can be used to inform institutional approaches in conjunction with other relevant research.

Literature review

Decision-making models

Substantial previous research offers a number of decision-making models and frameworks which can be applied to consumers in many sectors (Panwar et al., Citation2019; Shim et al., Citation2018). Early decision-making models were underpinned by the assumption that consumer behaviour followed a rational and logical approach, moving in a linear path with discreate, non-repeatable stages. However, more contemporary theories offer an iterative, multi-dimensional approach. Towers and Towers (Citation2020), in their review of numerous models, suggest that, in reality, the process is evidently more fluid, with the journey circular in nature, and consisting of multiple interactions and touch points. Further to this stance, McNicholas and Marcella (Citation2022, p. 9) indicate that university applicants move ‘backwards and forwards through the information search process stages’. This modern approach can include forays into digital and traditional information sources, via planned or spontaneous ventures and involve both rational and emotive behaviours (Cheong & Cheong, Citation2021; Straker & Wrigley, Citation2016).

Specific to the HE market, a number of contemporary decision-making models are evident. Towers and Towers (Citation2020) offer a framework that exhibits recognisable stages in terms of: problem recognition stage; information search; evaluation stage (i.e. applications); decision stage (i.e. course selection); and post purchase evaluation, and is circular in nature, with interactions between stages. They also postulate that influencers such as parents, friends and other agents impact the information search stage. Congruent with Towers and Towers (Citation2020) framework, Gai et al. (Citation2016) assimilate two previous models to propose a similar five-stage model applicable to the higher education marketing sector. However, building on the notion of different stakeholders having agency during the initial decision-making stages, they propose a linear-based model, but one where students can engage in a ‘multi-level interaction pattern’ (p. 191), allowing objective and subjective information to be communicated via a reciprocal dialogue. McNicholas and Marcella (Citation2022) go further and suggest an ‘iterative decision-making cycle model’ which illustrates the notion that applicants learn from their interactions during the process and move in a fluid manner at all stages. The complexity of relationships between variables at different stages of decision-making is evident in Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka (Citation2015) systematic review of research relating to HE choice. Here they theorise that a multitude of factors – from race, socio-economic group and family income; to perceived characteristics, image and benefits of institutions – influence the decision-making process often in a tumultuous and irrational way. The complex and multifaceted nature of these education-based models, and the variance between them, implies that during the decision-making journey for people who are inquiring about studying in the higher education sector, a complex and interactive, multidimensional dialogue occurs between many parties.

Touch points

During any information gathering stage, previous research has suggested that HE applicants seek details regarding many different factors, including: course curriculum (Dirin et al., Citation2021; Heathcote et al., Citation2020); financial considerations (Heathcote et al., Citation2020); future prospects (Bennett & Ali-Choudhury, Citation2009); and course and university reputation (Heathcote et al., Citation2020; Le et al., Citation2019). To gather this information, and throughout the decision-making journey, HE applicants experience encounters, or ‘touch points’, where they interact with institutions and other relevant stakeholders. Higher education is no different to other sectors influenced by neoliberal, competitive practices, and these direct or indirect interactive encounters with a brand (or in this case the university) significantly influence a consumer’s experience with the brand or organisation, and influence their choices based on the positivity and successfulness of each interaction (Baxendale et al., Citation2015). These touch points often transcend the different stages of proposed decision-making models, but in the context of deciding upon university admissions, they predominantly apply to the initial stages of the decision-making journey, in terms of information search and evaluation (Gai et al., Citation2016; Towers & Towers, Citation2020). Khanna et al. (Citation2014) offer five key pre-admissions touch points which broadly align with touch points experienced by consumers in other sectors, such as retail (Baxendale et al., Citation2015). Here, they postulate that potential applicants interact with establishments in terms of soft and hard infrastructures, word-of-mouth and media influence. The importance and significance of these touch point interactions and their impact on the decision-making process, cannot be understated. A common theme that emerges in research is the interaction with people who are currently involved with, or have previous experience of, the brand and/ or product; with these word-of-mouth or reputational perspectives having significant influence on applicants’ decision-making (Baxendale et al., Citation2015) and are a sought-after data set (Gai et al., Citation2016; Le et al., Citation2019; McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022). Building on this, the work of Sultan (Citation2018) suggests that the quality of relationship between a customer and provider is determined by the effectiveness of interactions at various touch points, with positive interactions resultant in higher levels of credibility and trust placed toward an institution or company. Therefore, how well potential applicants perceive touch point interactions will directly influence their decision-making process due to improving an applicant’s affinity with an institution, or conversely reducing it, if unsatisfactory correspondence occur. Thus, how these relevant stakeholders perceive and value a particular establishment or programme can directly influence student recruitment and should be of primary concern to recruitment teams within universities.

Digital touch points

Many prevalent touch point interactions are facilitated through digital media (Dirin et al., Citation2021). This phenomenon of using digital media for communication is common in almost all industries, and the way in which consumers choose a product or service has evolved significantly since the abundant use of social media and websites for transactional purposes (Jones & Runyan, Citation2016). In the digital era, the potential for more frequent and collegiate in nature interactions has increased significantly, and this has had an impact on the decision-making processes of consumers, particularly in the HE sector (Dirin et al., Citation2021; Galan et al., Citation2015). Research suggests that potential applicants use a large range of digital media such as: social media; YouTube; dedicated application comparison providers such as ChaseDream.com (Gai et al., Citation2016); as well as traditional websites and search engines, implying that discerning applicants use multiple and varied digital sources from which to gain decision-making information (Dirin et al., Citation2021). Indeed, research by Vannucci and Pantano (Citation2019) suggests that due to improved timeliness of information and higher levels of trust, consumers often have a penchant for digital touch points over people-based ones. Given the prominence that this form of communication now has, it can be argued that it has never been so important for the digital marketing capabilities and standards of HEIs to have a positive influence on applicants’ decision-making (Al-Thagafi et al., Citation2020).

Rational verses emotional appeal/ approaches.

A constant in decision-making models is the desire of consumers to acquire information, data and knowledge to inform their choice. Throughout the decision-making process, it can be argued that emotion and emotional choices are prevalent and important factor for institutions to consider (McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022). Therefore, emotion and emotional engagement during an interaction with an organisation influence the attitude and behaviour of a customer (Cheong & Cheong, Citation2021; Straker et al., Citation2015; Straker & Wrigley, Citation2016). As going to university is not just solely an academic venture, but involves a multitude of social, financial and cultural factors and interactions, there are emotional connotations attached to all elements, suggesting that an emotional appeal should be utilised in any marketing touch point to satisfy these considerations. However, the use of rational appeal is important when deciding upon services or products that are ‘think’ (Cheong & Cheong, Citation2021) or ‘high risk’ (Towers & Towers, Citation2020) – where factual information is key to allow an informed decision to be made, as the consequences may be long-lasting and/ or potentially significant. Therefore, recruitment touch points should service both the emotional and rational needs of an HE applicant – i.e, the need to feel emotionally attached at the (or to certain) touch point(s), and the need for clear and informative information to make a rational decision (Cheong & Cheong, Citation2021). The phenomena and effects of rational and emotive behaviour are not purely restricted to the applicant themselves, they can extend to other people close to them who influence and can affect their decision-making process. Haywood and Scullion (Citation2018) suggest that choosing an HEI and programme is a very emotive experience for an applicant’s parents, and one which can serious impact the relationship between parent and child. As to whether individuals take an emotional or rational approach, and at what stages or touch points these manifest themselves, is highly dependent on the individual and their personal characteristics and background (McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022). Therefore, a note of caution – applying any framework or model to encompass all applicants is highly problematic, as a single model or approach will not necessarily align with the values or perspectives of individuals or different groups (such as mature students vs. younger applicants) applying to study at UK based HEIs (Heathcote et al., Citation2020).

Methodology

The objective of this study was to establish decision-making behaviours of UC students, and primarily to identify any factors that influence students when choosing a further study, and the external influences and touch points that affect their behaviour.

The research design follows a phenomenological-based exploratory narrative approach, as this facilitates a more open dialogue for those who have lived the experience (Bold, Citation2012; Goulding, Citation2005). Three interviews were conducted with eight, second-year, level 3 vocational business and sport UC students, all from a single General FE college in the South of England. Each round of interviews was conducted in the final weeks of each academic term – December, April and July. To enhance research validity, the sampling process was informed using Robinson's (Citation2014) four point framework. The sample was selected through a combination of purposive and volunteer sampling (Patton, Citation2014), with all eligible UC students within the business and sport subject areas being presented with the opportunity to be involved in the research. The subject areas and groups were identified to cultivate participants from due to their practical proximity and the relatively high proportion of UC students within them, thus increasing the chances of securing an adequately sized sample (Robinson, Citation2014). A total of eight participants volunteered and were therefore recruited. A semi-structured interview approach utilising open-ended questions (Tracy, Citation2020) was selected to encourage individuals to share their experiences, insights and feelings (DeJonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019). Data was collected by staff employed as Teaching & Learning Coaches at the college utilised in the study.

The interview process represented a ‘flowing conversation’ (Choak, Citation2013) where the interviewer probed gently and incisively used tone to maintain the engagement and trust of the participant (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2005). This was particularly important as the interviews were all conducted digitally as this facilitated an effective way to complete the study (Lo Iacono et al., Citation2016). Individual interviews were chosen to give participants confidentiality from their peers, with the interviews following a naturalist approach which focused on the personal choices and experiences of those involved (Gubrium et al., Citation2012). Researchers endeavoured to remain impartial and portray a naïve stance (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2018); however, as they were linked to the funded SUN project, there is potential for their perceptions and individual bias to have had an impact on the interviews, in terms of the questions used and prompts given (Cohen et al., Citation2018).

As the phenomenon of decision-making within the UC population had not been explored explicitly in previous literature, a Grounded Theory (GT) approach (Goulding, Citation2005) to the analysis was utilised. This allowed the organic emergence of specific analytical foci during the data collection, rather than being predicated on previous perspectives exhibited by different demographic groups during their decision-making journey (Charmaz & Thornberg, Citation2021). This approach was employed to allow the inductive development of themes and any subsequent conceptual frameworks, therefore allowing a coherent but malleable research approach to be taken (Birks & Mills, Citation2022; Charmaz, Citation2014). Concurrent data collection occurred over the three interviews, with codes developed naturally from the iterative collection and analysis of the interview data (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017). This facilitated a comparative analysis of the data generated over the course of an academic year, allowing a sequential focus on the most pertinent emergent themes (Charmaz & Thornberg, Citation2021), thus enabling a comprehensive picture of the applicants’ decision-making journey to transpire and therefore a critical inquiry to occur (Birks & Mills, Citation2022). To encourage conceptual and theoretical development within a GT approach (Hutchison et al., Citation2010), NVivo 12 Plus software was used to facilitate the coding and analysis of the transcripts. Two researchers coded a set of transcripts independently to increase the validity and reliability of emergent themes (Ryan, Citation1999). To ensure a sound level of objectivity in data analysis, all information collected was transcribed, coded and utilised to prevent any bias and misrepresentation of the data (Cohen et al., Citation2018).

Results

The results of this study imply that students from a UC background seek multiple sources of information and interact with a multitude of touch points when making decisions – which were largely based on rational processes – regarding their post-college ventures. Primarily, immediate and easy-to-access individuals were utilised to gather information from and mould the decision-making process. For the participants, the information search and accumulation stage took many forms: searching the internet; internal recollections; discussions with parents; university visits and speaking to staff. Aligned with the findings of previous research (Heathcote et al., Citation2020), the results of this study infer that a singular model or framework cannot be applied to how UC students source their information, evaluate it and decide on an outcome, based on many factors and sources. As services are intangible, perishable, variable and inseparable (Palmer, Citation2014), this means that every student has a different experience based on their individual circumstances and perspective.

Key themes emergent in the data analysis, regarding interactions with touch points and logistical factors, will now be considered.

People: college tutors

The results of this study suggest that certain people have a significant influence on decision making – with college staff prominent protagonists. College tutors seem to play a significant role in exposing students to the potential of university as an option post-college. Due to their close bonds and relationships, college tutors had a significant influence on the decision-making process; more so than other stakeholders (such as parents, friends, etc.). It can be inferred that they are a key conduit for signposting options to students and relaying information. Fiona stated:

… [M]y law teacher has told me about law taster days, stuff like that, like, quite specified. But then my tutor … they email us quite a lot about just anything general to do with uni, and we get that fed through to us quite a bit, which is quite useful.

… [E]specially, my tutor, he’s been very good … he gives you information and then he explains positives and negatives for me and then you can work out yourself if it’s good. He makes you do what’s always best for you, which I think is good.

People: parents

The input of parents offers a divergent picture. Findings imply that they rarely play a direct role in informing the student’s choice of further study, but more often act as a passive conduit for UC students to articulate thoughts and perspectives, to help consolidate their decisions. Synchronous with other research (McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022), applicants’ parents play the roles of ‘initiators’ and ‘deciders’ regardless of whether the parents have gone to university themselves. As an initiator, parents predominately encourage their UC children to explore the possibility of university after college. Callum said:

I think the biggest conversation I’ve probably had is with my mum. She wants me to go to uni, she thinks it’ll be the best thing I’ve done.

And then I spoke with my mum. We realised that wasn’t a good career path to go down after, and if I want to go to uni … I could do the same thing if I want and just get in via an apprenticeship … my mum, she said, if you want to go to uni make sure, you need to go to uni …

Well, she just helped me compare … she just helped me compare everything and helped me figure out what was my best option

She just sort of … you know when you talk to someone and they just don’t really say much … but talking about it makes it easier to understand? It was basically that … my mum just sort of sat there and then I made my own mind up.

… [W]e still do have a little heated conversation every now and then about the finance and how it’s working.

I’ve spoken to my parents about it. They weren’t … financially, I don’t think they’re 100 per cent on it. They don’t understand how it’s going to work and they’re worried that I’ll just be paying it back or having loads of loans for years.

People: friends

In addition to parents, friends are a common audience to facilitate conversations and debates for UC students. This form of discussion is regularly available for students, especially with their peers at college. Interestingly, UC students suggest that the role friendship groups play in the decision-making process is as more of an informal and passive sounding board (similar to the interactions with parents discussed previously) giving reassurance that steps taken and aspects considered are aligned and consistent with peers, rather than as an active influential contributor to the outcome of the process. It seems that friends are primarily a tool to utilise to help shape an applicant’s decision about their HE application, rather than a determinant of whether to go to university or not, and whether to stay close to home, or move away.

My friend Lucy, we will always text each other and we'll talk about how we're going to open events or we're looking at all stuff online that they post. We'll look at that but it's more talking about what we've already done, not really asking for advice on what we're going to do …

Everyone’s pretty similar, to be fair, so it’s quite nice. We were just chatting about … we were just discussing our options basically and sort of, doing a pros and cons of each course for each other, which was nice, because obviously you could see it and visualise it.

Yeah, because obviously, it’s good to see other people’s opinions because they’re moving out, but obviously, I’m not … I think it made me feel, like, maybe I’m going to miss something if I don’t do it, but it hasn’t changed my mind. I still want to stay at home.

I talk to some of my friends outside of college, because we’re all going to different universities …

I have mates who are at uni now and mates who are going to uni, not in this college, and they’ve all gone to different unis, like X and Y. So it wasn’t really based on where they’ve gone and what they want to do, it’s just something which I thought would be good and the best for me.

… Quite a few of them have been saying ‘I’m not going to uni, you can go into a full-time job’. And then it’ll put in my head, oh, maybe I should go into a full-time job … And I just don’t need, shouldn’t do that.

I’m not like a lot of my friends, I don’t have a single friend that’s going to uni. And so that’s just the type of social circle I’m in, but it’s still kind of pushed me to go and make a plan for myself just because I have so of many of my close friends that don‘t have a plan. It scares me that they don’t have a plan.

With my friends, honestly, it’s more I made the decision and then I’ll talk to them about helping me. They’re helping with the decisions I’ve made after I’ve already made the decision to go to uni. But I’d probably say they didn’t influence me to go.

So, I had a word with my friends, I never really spoke about it because I knew they all wanted different things … They sort of just said, they just want to go full-time working and they just want to jump into it. Which is fair enough. I’d love to. But I feel like for me there’s more to learn and I feel I can get further if I do stay and go to uni. I feel like it would be better from a career wise, give it a few years. Whereas they’re quite happy to … not that it’s a bad thing, they’re quite happy and content to just go straight into it and trust that. Whereas … I sort of want that security of knowing that I can get something out of uni, and I’ll have a degree.

If anything, they were more of a reason not to go. Because at the moment … everyone’s buying all the festival tickets and all these concert tickets, there have been a few things that I can’t go to because I’m going to be in a different postcode. But again, that’s just one of the choices that I made, that I would sacrifice a few concerts, because I’m going to have lots more opportunities going up and broadening my education than I would staying here and getting sweaty in a concert.

So I have in mind to go to Y University because … a few of my mates from my course and college right now are going there and I didn’t want to be alone. But then again, I chose X university out of the fact that I need to do what’s best for myself.

I think it’s just knowing what is best for me, like this is the best course, I could go to Y and live down there with my friends, ‘cause loads of my friends are there, but it’s not something that’s … it won’t benefit me as much as going to X.

Digital touch points

Whether it is before speaking with tutors, or after, the university website is normally the first way that students interact directly with an education provider. Adam gives examples of his experience:

I went to the X webinar for strength and conditioning, and it was a pretty good course, and I was actually really wanting to do that … It was very informative. It gave all the info I actually wanted. It gave me a bit of … a view of the timetable and see how the courses works, the different semesters and … what actually goes on at X.

I looked at all the modules online and they did cover a wide variety of things, which was something that attracted me to the course as well.

Then their website had the course finder which I found really easy to use. Whereas I went onto X’s website and I just kept getting lost in the website and I couldn’t find any courses and that, so I just applied for four courses at Y.

Location

When discussing their options, the location of a university was often raised in relation to being close to home, friends and family, or being further away from home for the experience and independence. Those students that selected universities closer to home mentioned feelings of ‘not being ready’ (academically or for independent living). Hannah explained her reasons for wanting to stay at home. She said:

… I feel like it’s a bit out of my comfort zone. I still share a room now, I’ve never, like, had my own room. So the thought of being in a shared house with new people or even having my own little dorm or whatever the situation would be, and not just coming back home every night, it just wouldn’t … I don’t know, it wouldn’t sit right.

[I want to study further away] To experience something new, I don't want to stay at home the rest of my life obviously, go far and experience life and being my own independent person … X University, I mean that is my last choice, it's quite close. X University is just like Y University I guess, like obviously it's got more stuff in it, it's got a shopping mall and that, but it's basically just another city, X University is close, that's why the last choice, just to make my mum happy …

Well, it’s much closer and also I just want to be around a few of my friends. I still want to see people. Well X has been my home and I just want to stay within that circle. I’m not really too familiar with going to other places. But then at university Y, there’s more opportunities.

My friends all want me to go so they can come out and visit.

Financial implications

In addition to the location of a university, financial implications had a significant impact on the decision-making process of those students interviewed. The importance of finance has long been a factor in the decision-making process for HE applicants (Usher et al., Citation2010). Uni Connect students indicated that they engage with multiple sources of support regarding the financial impact and implications of going to university. The conversations focused on establishing ‘would it be worth it’ rather than establishing the actual costs, how to apply and the time scale and salary scale for contribution for repayment. Blake summarised his experience of these conversations:

Well, I feel like everyone says it’s a lot of money but it should, in theory, end up being worthwhile, that’s generally the message I hear from that which, yeah, would match with what’s been said at home.

So, the main thing that we’re all concerned about, our whole group was concerned about was the student loan and how … well you might be in debt for the next ten years if you don’t pay back your student loan. So, that’s something I would be kind of worried of, but I know in the end I can probably do it if I actually start finding a part-time job and actually start paying it off with that.

Having to work everything out financially and trying to get some support with that. Because obviously, when you start looking into UCAS and you get people going through it with you, you don’t realise how much it is financially, how much you have to pay for, what you have to pay for, that sort of thing. You don’t … I didn’t realise how much was sort of behind it and it’s not just you join a course and you go, it’s a lot.

I mean I’m not worried about the work because I always get that done, that doesn’t worry me. The only thing that does worry me is the money, I know I'm going to spend a lot of that and quickly.

But at the moment, I am actually working two jobs, so I’ve taken on another job, so I’m working full-time, and then I’ve got another part-time job at the moment, just so I can have enough money saved up so that when I do move up there, I can go a couple of months while I’m looking for a job, if it comes to it.

Discussion

College tutors

Whilst the careers service is often an essential part of college support services, contemporary research has shown that this service is less influential than teachers and tutors when students are selecting their future study path (Dirin et al., Citation2021). The results of the current study concur with this position, suggesting that UC students spend longer with, and value the views of their college tutors more than those the careers professionals they interact with. Students seem to be swayed by their tutor’s personal views and experiences. They trust their judgement and value their perspectives due to the relationship that the student themselves have with them (Giles, Citation2011) and this can be a powerful cursor to a decision particularly if they have a positive perception of that particular member of staff (Karpouza & Emvalotis, Citation2019). From a marketing perspective, this suggests that if universities invest time in educating college tutors in terms of their institution’s offerings, activities and experiences for students, this may result in more positive exposure for their establishment. Interaction with tutors who have previous experience or knowledge of a specific course or institution, influenced UC students in terms of focusing or prioritising their search area towards specific courses and institutions. Therefore, how college tutors perceive and value a particular establishment or programme can directly influence student recruitment and should be of primary concern to managers and recruitment teams within universities. If a tutor’s views are out-dated, biased or they do not have a full picture of the options available, then students may make decisions without all the correct information. Therefore, it is recommended that universities look to provide updates and specific training or experiences for college staff (both teaching and careers-based) so that they can impart a current and valid narrative, from potential universities that their students may be considering.

Parents

The results of this study insinuate that parents can either take an active or passive role in the decision-making process of UC students. Both approaches seemed to be productive and indicate that parents initiate a predominately rational response to the decision-making process, rather than influencing on an emotive level (Cheong & Cheong, Citation2021). Parents play an important role in the decision-making process, but it seems impossible to establish an exact way in which to propose a model or framework of their influence, as there is no universal way in which they contribute through their initiator and decider roles. The success of the parent in the role of decider is dependent on the individual relationships that UC students have with their parents. As implied by Haywood and Scullion's (Citation2018) work, relationships between parents and their UC children are affected during this period, with some contentious conversations occurring if parents were not the initiators as to their children exploring the possibility of HE study. Congruent with Callender and Melis (Citation2022) work, this suggests that financial worries and implications are paramount for parents of UC applicants, and that they are at the fore-front of their minds, influencing their behaviour when they interact with their children and the decision-making process. Given the socio-economic situation of the UC families, this is not surprising. This level of concern for such an important life decision could contribute to the decline of the parent–child relationship, through the emotive dialogue observed in this study, during the child’s transition from college to university or employment. Haywood and Scullion (Citation2018) suggest that relationship maintenance is a key desire of parents during these interactions, therefore, it could be suggested that HEI communications to, and interactions with, the parents of UC students should focus on allaying their fiscal concerns and offering sound financial advice. This may help reduce the intensity of parental concerns and diminish the potential for conjecture or contentious discussions, as they often underestimate the level of financial support for which applicants may be eligible (Usher et al., Citation2010). It could also be suggested that HEIs allocate resource to ensure that parents who wish to take a proactive role in the decision-making process with their children have the tools and strategies to ensure a productive dialogue with them (Haywood & Scullion, Citation2018).

Friends

The results of this study align with the findings of Holmegaard et al. (Citation2014) who postulate that applicants do not utilise peers to inform their decision-making process when it comes to HE choices. They are independent, and are able to consider decisions that are bespoke to them and different from members of their peer group. This illustrates that, despite social and peer pressure, UC students make decisions primarily based on rational choices and perspectives, and that longer-term benefits took priority over short-term social gain (Bennett & Ali-Choudhury, Citation2009; Heathcote et al., Citation2020; Le et al., Citation2019).

While the participants expressed the importance of friends to discuss their futures with, ultimately the decision about their next steps was not one that was strongly influenced by their peers. Friends offer a mechanism by which to debate and discuss choices, but the results of this study imply that this is to seek reassurance that certain aspects have been considered and that UC students have followed the same processes as their peers, rather than a case of friends’ actions and opinions directly affecting a decision to attend university or not. What is evident with tutors, parents and friends, is that interactions take place on a rational level, with UC students using these stakeholders to inform their decision-making process in a judicious way rather than on an emotive plane. This insinuates that, like other consumers making ‘high risk’ decisions (Cheong & Cheong, Citation2021; Towers & Towers, Citation2020), potential UC applicants to HE make rational decisions due to the nature and future implications of choosing an undergraduate course, and that emotional attachment to friendship groups doesn’t significantly influence the outcome of their decision-making processes (Heathcote et al., Citation2020; Holmegaard et al., Citation2014; Le et al., Citation2019).

Digital touch points

Previous research by Moogan (Citation2020) and McNicholas and Marcella (Citation2022) has suggested that online sources are held in a high regarding in terms of credibility and authority, and are a key driver in the decision-making process of university applicants. Having a website that not only attracts new students but services the needs of current students, staff and other stakeholders is seen as essential in Higher Education where usability is considered the key credential of effective higher education website design (Manzoor et al., Citation2012). How UC applicants interact and value digital touch points fully supports this stance. This corresponds with much research regarding the usability of websites as a marketing tool or consumer transactional site for users from all backgrounds (Ageeva et al., Citation2019; Fatima et al., Citation2020; Schmutz et al., Citation2018) all of which suggests that consumers are deterred from engaging with an organisation if the information they require isn’t accessible or available in a timely manner. Therefore, it can be suggested that digital services which are easy to navigate and use are an influential factor in the decision-making process of UC students, as this enables them to receive and absorb relevant information from which to choose an institution. Limited information and/ or onerous to use digital platforms may lead to an applicant refraining from choosing that institution.

As suggested by the experiences of participants in this study, it can be inferred that exposure to the course structure and curriculum during an early interaction and touch point can have a significant impact on decision-making, due to the importance that the course curriculum has in course and university selection (Dirin et al., Citation2021; Heathcote et al., Citation2020). This supports Le et al.'s (Citation2019) findings that course content is one of the top-ranked information sources (second only to degree reputation) sought by potential students looking to make an informed choice about university and university course. The reason for this may be the prevalence of extrinsic motivational drivers (career prospects, earnings, etc.) for students, in place of more intrinsic preferences, such as the love of a subject (Maringe, Citation2006), ultimately due to the burden of funding (predominately via student loans) falling on the student themselves.

Touch points: proposed model

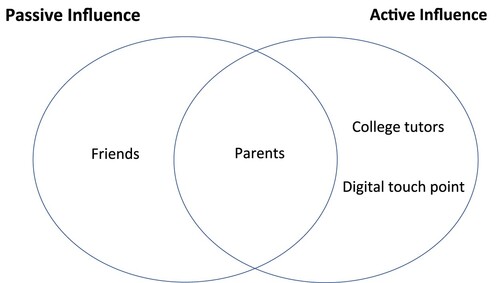

The pertinent findings regarding the active and passive ways in which UC students interact with different touch points can be synthesised into a contextualised framework. illustrates the nature of the relationship between touch points and UC students with regard to active and passive influence. A Venn diagram captures the differing nature of whether a touch point is equivocally used in an active or passive way, to directly influence the decision-making process, or has the duality of being either passive or active dependent on individual UC students.

Here we can see the different roles the four touch points play. Friends are passive in the process and facilitate a reflective opportunity for applicants and do not actively inform the decision-making process for UC students. Conversely, interactions with college tutors and university digital mediums, do actively influence the decision-making process. Dependent on individual applicants, parents transcend the conceptual spheres and can be either a passive or active influence dependent on individual circumstances. A note of caution: this is a tentative model to help illustrate the current participants’ thoughts and perspectives. Further research with a wider reach, would be needed to confirm its accuracy and seek to explore how additional touch points might relate.

Location

There is limited previous research into how the location of an institution is portrayed or marketed. Winter and Thompson-Whiteside (Citation2017) suggest that HE marketing professionals believe that students seek excitement from coming to university and that much marketing material around location is constructed to speak to that ideal. However, this notion is not completely supported by the results of the current study; there is evidence of a real dilemma for UC students. Therefore, from the results of this study, no unequivocal inference can be offered, other than that location is a consideration during the decision-making process, that it is an emotive aspect, and that many factors influence a UC student’s decision to study at a HEI close to home or further afield. This dichotomy of perspectives is interesting and resonates with research conducted by Bennett and Ali-Choudhury (Citation2009), who suggest that first-generation university students ranked location as a critical factor for them. This suggests that recruitment teams within universities should initially establish how much importance an individual places on either wanting the security of staying locally and being close to home support, or looking for freedom and ‘adventure’; and then compare it with their distance from the university to decide whether to target specific resources towards them or not. However, this ambivalent and irresolute behaviour towards location displayed by UC students does not align with the decision-making processes of international students, which suggests that location in terms of choice of city ranks behind other key elements (Manns & Swift, Citation2016; McNicholas & Marcella, Citation2022). Therefore, it can be suggested that the decision-making process for UC and international students is different when it comes to location as a factor. Location is less clear cut as a driver for UC students and is a potential source of dilemma for this group.

Financial implications

Uni Connect students can be classified as what Callender and Melis (Citation2022) term as ‘managing costs’ students, whereby financial factors are a consideration for the decision-making process and subsequent behaviours and strategies are initiated to address issues and concerns. However, financial factors do not dictate the decision-making process and therefore UC student choices aren’t governed by the economics of HE costs. The current study suggests that the financial implications of going to university, both in the short-term whilst studying, and in the long-term with regards to paying back any student loans, are key considerations for UC students. Supporting the report by Usher et al. (Citation2010), the results of this study suggest that although UC students aren’t deterred from university by the cost implications (Callender & Melis, Citation2022), any support the university can offer in terms of students finding jobs, but also to reassure them that their longer-term financial position will be enhanced by going to university, would be beneficial, particularly if students could have this information during their decision-making phases.

Conclusions

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the validation of previous research exploring applicant decision-making processes and offers a series of theoretical positions. Previous research has suggested that a singular information source is not enough on which to base an applicant’s decision whether to go on to higher education, and if so, at which university and on which course to study (Dirin et al., Citation2021; Gai et al., Citation2016; Galan et al., Citation2015; Khanna et al., Citation2014; Towers & Towers, Citation2020). The results of the current study confirm that applicants from a UC socio-economic background engage with a variety of sources of information and stakeholders to inform their decisions. This behaviour reinforces the predominately rational approach and thought process taken when utilising the multitude of touch points available to UC students. Overwhelmingly, they appear to exhibit rational behaviour due to the long-term and potentially life-course altering decision that they are making regarding their future (Cheong & Cheong, Citation2021; Towers & Towers, Citation2020). The use of multiple information sources in a non-sequential way, and the use of different touch points dependent on individual approaches, with no equivocal or homogenic pattern emerging, suggests that UC students take an iterative approach to their decision-making, as proposed by McNicholas and Marcella (Citation2022). Further to this, the approach, use and impact of different touch points is unique to individual UC students, and the decision-making process appears to be individualised for each person. Thus, an exact collective model or framework is almost impossible to suggest due to the near infinite range of possible interconnections between each of the different factors (Heathcote et al., Citation2020).

Various touch points, and the context in which these interactions are experienced, play a significant role in influencing university choice for UC students. This aligns with findings in other sectors, which suggest that positive experiences with these types of touch point result in more significant consideration of a product or service (Baxendale et al., Citation2015; Sultan, Citation2018; Towers & Towers, Citation2020), and that these perceptions are stable over the long-term (Cambra-Fierro et al., Citation2021). Concurrent with previous research (Baxendale et al., Citation2015; Gai et al., Citation2016; Le et al., Citation2019), it appears that people who influence students during their decision-making journeys, do play an important role in the information search stage of the process. As far as parents and friends are concerned, there appears to be no single or definitive position that these parties take in terms of influencing the decision-making process. Predominately, parents and friends played a passive role in the decision-making process, primarily as a sounding board to allow the consolidation of a UC student’s thoughts and to aid formulation of their own decision, rather than directly contributing to the consideration of certain choices and options (Holmegaard et al., Citation2014). These findings are summarised in and illustrate whether the touch points have an active or passive influence on the decision-making process.

Practical implications

The insights into the decision-making process for UC students demonstrate the importance of universities, tutors and others, in supporting students when they are making decisions regarding their futures post-college. Due to the complexities of UC students’ decision-making, and it being multifaceted and multifarious, ensuring advice and guidance is targeted at multiple sources and a variety of touch points, is essential. If the UK government is serious in its desire to support access to higher education for all students regardless of background, and in reducing the gap in higher education participation between the most and least represented groups (Office for Students, Citationn.d.), it can be recommended that advice, support and guidance regarding the benefits and realities of studying at an HEI, is allocated and driven via public and regulatory bodies that can ensure resources are being targeted at the touch points identified in this study. Ensuring these touch points can offer pertinent, valid and current information will support the making of an informed decision by potential applicants.

At an operational level, outreach and marketing ventures by HEIs towards UC students should incorporate the utilisation of various touch points, with interaction through multiple but integrated touchpoints, a desirable approach. Primarily these actions and subsequent resources (both human and financial) should be targeted towards and prioritise the active touch points identified in , with the two key elements of college tutors and digital media being paramount. Where possible HEIs should prioritise key feeder FE colleges to ensure course tutors are up-to-date with information regarding the institution itself and programmes on offer. Although many HEIs will have existing relationships with the careers service within colleges, they should look to reach beyond this and look to affect the key touch point of college tutors, thus improving the chances of attracting UC students. Similarly, regular reviews and revisions to an HEI’s digital media to ensure easy access to desirable key information, are essential as UC students are deterred by a poor experience when interacting with a website or social media. The use of a framework to support this digital media review process is recommended, and universities should look to aspire to a minimum of ‘level 3 maturity’ in terms of the AIDA marketing communications model (Al-Thagafi et al., Citation2020).

Suggestions for further research

Although the current study elucidates the nature of the decision-making process for UC students, it does have a few limitations that could offer direction for future research endeavours. First, the participant base limits the generalisability of the findings due to the single institution and constrained subject areas from which participants were drawn from. Although trends established with this cohort may be reflected in other UC student populations – studying other arts, humanities or science-based subjects; or in other geographical locations within the UK for example – future research should consider using a broader UC demographic to explore the position and inferences offered by this study.

Second, although offers a contextualised framework as to the interaction and relationship between the active and passive influences established by this study, it would benefit from a deeper exploration of the salient elements. Future studies should further investigate the touch points to establish to what extent sub-groups within each touch point – college subject lecturers, pastoral leads; or college friends, work friends and wider friendship networks, for example – are active or passive as touch points within the decision-making process. Along with the suggestions in the first point above, this would potentially improve the reach of the findings, be an opportunity to test the proposed conceptual model and allow wider application of practical and theoretical implications.

Third, the findings relate to UK students who are classified under the umbrella term of UC students. Caution is needed when applying generalisations to similar social-economic populations in other countries or states. Given that the nature of the UC classification is fairly specific, applying findings to other widening participation groups, contexts or as part of any social mobility narrative, is hazardous, and further research would be needed to ascertain any commonalities or congruities between decision-making approaches for similar demographic groups.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ageeva, E., Melewar, T. C., Foroudi, P., & Dennis, C. (2019). Evaluating the factors of corporate website favorability: A case of UK and Russia. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 22(5), 687–715. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-09-2017-0122

- Al-Thagafi, A., Mannion, M., & Siddiqui, N. (2020). Digital marketing for Saudi Arabian university student recruitment. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 12(5), 1147–1159. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-05-2019-0119

- Baxendale, S., Macdonald, E. K., & Wilson, H. N. (2015). The impact of different touchpoints on brand consideration. Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.12.008

- Bennett, R., & Ali-Choudhury, R. (2009). Prospective students’ perceptions of university brands: An empirical study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 19(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841240902905445

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2022). Grounded theory: A practical guide (3rd ed.). Sage Publications Limited.

- Bold, C. (2012). Using narrative in research. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446288160.

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2018). Doing interviews. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529716665.

- Callender, C., & Melis, G. (2022). The privilege of choice: How prospective college students’ financial concerns influence their choice of higher education institution and subject of study in England. The Journal of Higher Education, 93(3), 477–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1996169

- Cambra-Fierro, J., Polo-Redondo, Y., & Trifu, A. (2021). Short-term and long-term effects of touchpoints on customer perceptions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102520–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102520

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Grounded theory in global perspective. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(9), https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414545235

- Charmaz, K., & Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357

- Cheong, H. J., & Cheong, Y. (2021). Updating the foote, cone & belding grid. Journal of Advertising Research, 61(1), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2020-014

- Choak, C. (2013). Research and research methods for youth practitioners. In S. Bradford, & F. Cullen (Eds.), Research and research methods for youth practitioners (pp. 90–112). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203802571

- Chun Sing Ho, M., & Lu, J. (2019). School competition in Hong Kong: A battle of lifting school academic performance? International Journal of Educational Management, 33(7), 1483–1500. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2018-0201

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th Ed). Routledge.

- DeJonckheere, M., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Dirin, A., Nieminen, M., & Alamäki, A. (2021). Social media and social bonding in students’ decision-making regarding their study path. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 17(1), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJICTE.2021010106

- Dowling-Hetherington, L. (2020). Transnational higher education and the factors influencing student decision-making: The experience of an Irish university. Journal of Studies in International Education, 24(3), 291–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315319826320

- Fatima, K., Bawany, N. Z., & Bukhari, M. (2020). Usability and accessibility evaluation of banking websites. 2020 International conference on advanced computer science and information systems (ICACSIS)., 247–256. 17-18 October 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACSIS51025.2020.9263083

- Gai, L., Xu, C., & Pelton, L. E. (2016). A netnographic analysis of prospective international students’ decision-making process: Implications for institutional branding of American universities in the emerging markets. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2016.1245233

- Galan, M., Lawley, M., & Clements, M. (2015). Social media’s use in postgraduate students’ decision-making journey: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 287–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1083512

- Giles, D. (2011). Relationships always matter: Findings from a phenomenological research inquiry. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(6), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2011v36n6.1

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206

- Goulding, C. (2005). Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology. European Journal of Marketing, 39(3/4), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560510581782

- Gubrium, J., Holstein, J., Marvasti, A., & McKinney, K.. (2012). The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218403.

- Haywood, H., & Scullion, R. (2018). It’s quite difficult letting them go, isn’t it?’ UK parents’ experiences of their child’s higher education choice process. Studies in Higher Education, 43(12), 2161–2175. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1315084

- Heathcote, D., Savage, S., & Hosseinian-Far, A. (2020). Factors affecting university choice behaviour in the UK higher education. Education Sciences, 10(8), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10080199

- Hemsley-Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2015). University choice: What do we know, what don’t we know and what do we still need to find out? International Journal of Educational Management, 29(3), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-10-2013-0150

- Holmegaard, H. T., Ulriksen, L. M., & Madsen, L. M. (2014). The process of choosing what to study: A longitudinal study of upper secondary students’ identity work when choosing higher education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.696212

- Hutchison, A. J., Johnston, L. H., & Breckon, J. D. (2010). Using QSR-NVivo to facilitate the development of a grounded theory project: An account of a worked example. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(4), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570902996301

- Jones, R. P., & Runyan, R. (2016). Conceptualizing a path-to-purchase framework and exploring its role in shopper segmentation. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 44(8), 776–798. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-09-2015-0148

- Karpouza, E., & Emvalotis, A. (2019). Exploring the teacher-student relationship in graduate education: A constructivist grounded theory. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1468319

- Khanna, M., Jacob, I., & Yadav, N. (2014). Identifying and analyzing touchpoints for building a higher education brand. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 24(1), 122–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2014.920460

- Le, T. D., Dobele, A. R., & Robinson, L. J. (2019). Information sought by prospective students from social media electronic word-of-mouth during the university choice process. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1538595

- Le Grand, J. (2010). Knights and knaves return: Public service motivation and the delivery of public services. International Public Management Journal, 13(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967490903547290

- Lo Iacono, V., Symonds, P., & Brown, D. H. K. (2016). Skype as a tool for qualitative research interviews. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3952

- Manns, Y., & Swift, J. (2016). Chinese postgraduate choices when considering a UK business and management programme. Higher Education Quarterly, 70(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12080

- Manzoor, M., Hussain, W., Ahmed, A., & Iqbal, M. J. (2012). The importance of higher education website and its usability. International Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 1(2), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.14419/ijbas.v1i2.73

- Maringe, F. (2006). University and course choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(6), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540610683711

- McNicholas, C., & Marcella, R. (2022). An interactive decision-making model of international postgraduate student course choice. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2022.2076276

- Moogan, Y. J. (2020). An investigation into international postgraduate students’ decision-making process. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2018.1513127

- Office for Students. (n.d.). Uni Connect. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/promoting-equal-opportunities/uni-connect/

- Palmer, A. (2014). Principles of Services Marketing (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Higher Education

- Panwar, D., Anand, S., Ali, F., & Singal, K. (2019). Consumer decision making process models and their applications to market strategy. International Management Review, 15(1), 36–44.

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice - michael quinn patton - Google Books. Sage Publication.

- Rafi, M. A. (2018). Influential factors in the college decision-making process for Chinese students studying in the U.S. Journal of International Students, 8(4), 1681–1693. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1468068

- Rembielak, G., Rashid, T., & Parlińska, A. (2020). Factors influencing students’ choices and decision-making process: A case study of Polish students studying in a British higher education institution. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum. Oeconomia, 19(3), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.22630/ASPE.2020.19.3.31

- Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

- Royo-Vela, M., & Hünermund, U. (2016). Effects of inbound marketing communications on HEIs’ brand equity: The mediating role of the student’s decision-making process. An Exploratory Research. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(2), 143–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2016.1233165

- Rubin, H., & Rubin, I. (2005). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226651.

- Ryan, G. (1999). Measuring the typicality of text: Using multiple coders for more than just reliability and validity checks. Human Organization, 58(3), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.58.3.g224147522545rln

- Schmutz, S., Sonderegger, A., & Sauer, J. (2018). Effects of accessible website design on nondisabled users: Age and device as moderating factors. Ergonomics, 61(5), 697–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139.2017.1405080

- Shim, D., Shin, J., & Kwak, S.-Y. (2018). Modelling the consumer decision-making process to identify key drivers and bottlenecks in the adoption of environmentally friendly products. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1409–1421. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2192

- Straker, K., & Wrigley, C. (2016). Emotionally engaging customers in the digital age: The case study of “Burberry love.”. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(3), 276–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-10-2015-0077

- Straker, K., Wrigley, C., & Rosemann, M. (2015). Typologies and touchpoints: Designing multi-channel digital strategies. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 9(2), 110–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-06-2014-0039

- Sultan, A. J. (2018). Orchestrating service brand touchpoints and the effects on relational outcomes. Journal of Services Marketing, 32(6), 777–788. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-12-2016-0413

- Towers, A., & Towers, N. (2020). Re-evaluating the postgraduate students’ course selection decision making process in the digital era. Studies in Higher Education, 45(6), 1133–1148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1545757

- Tracy, S. J. (2020). Title: Qualitative research methods collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Usher, T., Munro, M., Pollard, E., & Sumption, F. (2010). The Role of Finance in the Decision-making of Higher Education Applicants and Students (Findings from the Going into Higher Education Research Study). Department for Business Innovation and Skills (BIS). https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/resource/role-finance-decision-making-he-applicants-and-students.

- Vannucci, V., & Pantano, E. (2019). Digital or human touchpoints? Insights from consumer-facing in-store services. Information Technology & People, 33(1), 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-02-2018-0113

- Winter, E., & Thompson-Whiteside, H. (2017). Location, location, location: Does place provide the opportunity for differentiation for universities? Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(2), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2017.1377798