ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the presence of support information on university websites, with a specific focus on care-experienced young people. Engaging with extant research about the university and college choice process as it involves marketing of higher education internet sites, the paper is based on a national scan of equity support provision on Australian university websites. This paper posits that there is an extra element in the ‘phased decision-making’ for people with additional needs in universities that is yet to be recognised by higher education institutions in Australia. The website scan and analysis found significant gaps in essential information for care-experienced young people and highlights that current practices on institutional websites concentrate on marketing. The lack of information for applicants with additional needs arguably deepens disadvantage and the marketised nature of higher education information contradicts the tertiary goals of equitability of access.

Introduction

People with care experience are individuals who have experienced removal from their parental or guardian home during childhood. Children can enter into care as a result of allegations of neglect, abuse, death of family members or inability of family members to care for them. When removed, children may stay with relatives in a kinship care arrangement, foster care or residential care, e.g. a group home (AIHW, Citation2020). This study aims to explore the knowledge that universities have of the challenges to the enrolment of students with care experience. The research investigates how higher education institutions publicise types of specific supports available for people who have experiences of care.

Harvey et al.’s (Citation2015) Australian study into access to higher education for care leavers, found that there was a ‘lack of formal assistance and information when applying for university’ (p. 5). The lack of encouragement by the institutions to attend higher education is notable, particularly with a range of research that says this is a critically important step specifically for care-experienced people (Mendes et al., Citation2014; Michell, Citation2012; Michell & Scalzi, Citation2016). For instance, Australian research (Pollard, Citation2018) has also found that there is little information about the extra financial costs of higher education and even course fees which is particularly a problem for care leaver students returning to higher education later in life, especially when they have work responsibilities. The author’s own research (Knight & Colvin, Citation2021), using both quantitative and qualitative Australian data, traces the link between the lack of information for prospective students who have experiences of care and how this can become a barrier to enrolling in higher education.

Lack of information on university websites is not the panacea to institutional barriers to higher education participation experienced by equity groups, but we argue that it is important to consider because it can limit and constrain how care-leavers make important choices about their futures. Archer (Citation2007) writes of the difference between those students with less privilege: ‘they are rendered immobile and fixed to less powerful spaces, from which they lack the resources to become mobile’ (p. 54). It is this that suggests that there is a certain incompatibility between marketing of higher education institutions and central importance of providing requisite information for students with specific needs as Reay et al. (Citation2001) wrote:

… it is evident that the diversity of students within higher education does not constitute a field of equal players/consumers. Instead, we see hierarchically positioned actors who possess unequal resources with which to effect their ‘choices’. (p. 645)

Researchers also highlight that individual factors can shape the perspectives of care-experienced young people, which can create barriers to university enrolment (Bluff et al., Citation2012). Bluff et al. (Citation2012) interviewed nine care-leavers from the UK, with participants reporting that they saw university enrolment as outside the scope of what was expected of ‘foster children’ in general, coupled with few role models and very little support from carers. Conversely, this research indicates that it is not an issue with marketing that stops care leavers from accessing higher education but a number of individual and institutional factors that are likely at play when thinking about higher education transitions for care-experience people. Hence improving marketing is clearly good in itself but there are more complex structural factors that can be attributed to the underrepresentation of care leavers in higher education such as flexible systems for leaving care, psychological support during transition and general support networks (Atkinson & Hyde, Citation2019).

At the same time, we argue that the lack of information around financial support is crucial for this group in the process of university enrolment. Whilst websites and marketing may play a small role in a much larger and complex picture of equity and access as it relates to care-experienced people. We argue that information, particularly about financial, wellbeing and accommodation supports can be important to broader conversations about widening access and enacting equity for care leavers as one particular marginalised group. As such, this research aims to explore the nature of information presented on 39 Australian university websites as it relates to care-leavers.

Literature review

A significant body of research demonstrates that care-experienced people and ‘care leavers’, those who leave the care system as teenagers, are less likely to attain educational qualifications, less likely to have good health, and are more likely to have contact with the criminal justice and mental health systems (Mendes et al., Citation2014; Michell, Citation2012). Their participation rates in higher education are low and care-experienced school leavers are three-times less likely to enrol (Michell & Scalzi, Citation2016). Some care leavers do go to university, but more could if they were encouraged to do so (Tilbury et al., Citation2009).

Internationally, the educational achievement of care leavers is consistently lower in comparison to non-care leavers across age cohorts. This is echoed in other country contexts, for example in the EU a project ‘YiPPEE’ reported that care leavers in England, Denmark, Sweden, Spain and Hungary, performed lower than students not in care in each country (Jackson & Cameron, Citation2012). The YiPPEE project also showed that only around 8 per cent of young care leavers go on to higher education, which is five times fewer than young people overall (Jackson & Cameron, Citation2012). In line with this growing international research for people leaving state sponsored care (Jackson et al., Citation2003; Jackson & Cameron, Citation2012), Harvey et al. (Citation2015) argue that ‘it is important to examine the progression of [care leavers] into higher education nationally, and the factors that might increase aspirations, access, and success at university’ (p. 11).

Systematic reviews of care-leavers’ perceived barriers to higher education enrolment indicate that they see housing, social and financial support, as well as access to mental health supports and services as important facilitators of university engagement (Atkinson & Hyde, Citation2019). Given these perceptions of need, this study aims to explore the knowledge universities have of the challenges for care-leavers and how they publicise what specific support is available for them. In the next section, we present our consideration of the current literature on issues around marketing to prospective students from equity groups.

Those who do enter higher education face significant challenges from childhood trauma that may adversely affect their studies. Higher education is linked to positive lifelong outcomes for graduates such as improved employment opportunities and earning potential (Lomax-Smith et al., Citation2011; Norton, Citation2012) and evidence suggests that Australian care leavers rarely transition to higher education (Harvey et al., Citation2015; McNamara et al., Citation2019) despite increasing rates of school completion (McDowall, Citation2020). Although there is growing evidence to suggest that some care leavers enrol in university later in life (Wilson & Golding, Citation2016).

It is arguably important that information about transition to universities is not seen as purely a direct line from schools as research indicates that young people with care experience can require additional support. Harvey et al. (Citation2017) conducted interviews with 25 young people with care experience who enrolled in two universities the participants highlighted the importance of securing accommodation and funding support. Since some care experienced individuals have experienced trauma, Mendes et al. (Citation2014) make the distinction between relational and material supports, both of which they argue, are important to positive educational transitions. Hence, information, financial and material support, such as accommodation for care experienced students will feature in the university website scans.

The analysis of institutional websites has been growing alongside the rapidly changing nature of internet-based marketing (Bennett et al., Citation2017; Divan et al., Citation2019; Graham et al., Citation2013; Lewin-Jones, Citation2019). Marketing is costly and resource-consuming (Wu & Naidoo, Citation2016) and Munro (Citation2018) shows that digital technologies have been used as tools for advancing and intensifying the marketisation of higher education, in this case in the United Kingdom (UK).

For instance, Saichaie and Morphew (Citation2014) in the United States (US) found that websites played an important role in the university search process by communicating messages about the purposes of higher education and the brand of the institution. Morphew et al. (Citation2018) further detailed how public statements by institutions are revealing of institutional strategic plans. Their work showed how analysis of published information can show division and blur boundaries between their publicly espoused and privately held missions (Morphew et al., Citation2018). McCaig (Citation2018) in the UK, finds that the marketing of higher education institutions for widening participation purposes is sometimes performed cynically. Graham et al.’s (Citation2013) investigation about how institutions presented issues of widening participation on their institutional websites surfaced issues around the different statuses of institutions, concluding that there was significant inconsistency in how marketing materials of institutions presented important financial and support information for students.

The issue about the difficulties of finding information spread throughout websites is a major issue to understanding information and reader confidence (Davis et al., Citation2019). This study found that there were fundamental design issues with public-facing elements of college and university websites and highlighted issues where improvements could be made, particularly in clear and easily understandable language, navigational tools and aligning and interconnectedness of information. Davis et al. (Citation2019) argued that institutions should bring greater awareness to the assumptions that are integrated into the presentation of information on higher education websites – specifically invoking the assumption that most students may live at a parental home or have equivalent support.

The issue of sensitivity to assumptions that are baked into the design and development of higher education websites is critical for understanding where the barriers are for students from equity groups. The foregrounding of marketing purposes at the expense of functional information has potentially detrimental consequences to the promotion of fair access for disadvantaged groups. Equity and diversity information has appeared on websites for a significant period; however, it has only been belatedly demonstrated empirically by Ihme et al. (Citation2016) that the presence is important and very much not just a symbolic gesture.

Stensaker et al. (Citation2019) contend that university websites are sites for struggle and performance and have status-stratified practices that homogenise needs. This homogenisation of marketing materials has been identified as raising equity issues and causing barriers to fair access (Knight, Citation2020). In an Australian context, Drew (Citation2013) finds that school websites construct themselves as elite and promulgate the production of competition and their marketing function overtakes their administrative functions and overwhelms other concerns, perhaps including information needs of students (Davis et al., Citation2019). As seen in the next section, there is significant discussion about higher education marketing’s incompatibility with equity and this is a core theme for this article.

Issues of promoting the university as an equitable institution is another part of marketing. Luzeckyj (Citation2009) suggests that equity discourses in marketing which are presented as being open to anyone regardless of background are seen as a marketing strategy not a serious engagement with equity. Lewin-Jones (Citation2019) work investigating internationalisation on the websites of elite and non-elite higher education institutions in the UK found that discursive strategies of websites frame or side-line different disadvantaged groups by mobilising digital technology strategies. For example, the information needs of students from identified equity groups or from non-traditional backgrounds are intensified as Davis et al. (Citation2019) found ‘underrepresented students face disproportionate challenges in navigating informational resources’ (Davis et al., Citation2019, p. 2). These issues with navigating information as Davis et al. (Citation2019) explain, align with Australian bodies of research that develop the concept of navigational capacity (Gale & Parker, Citation2015) where they draw on Appadurai (Citation2004):

For Appadurai (Citation2004), the difference between impossible possibilities and reasonable possibilities is navigational capacity and the archives of experience accumulated from previous successful navigations (of one’s own but also the successful experiences of family and community). (p. 147)

Gale and Parker’s (Citation2015) presentation of navigational capacity draw on de Certeau’s (Citation1984) work and concepts of ‘tour’ and ‘map’ knowledge. It contrasts the prospective student with knowledge of higher education choices gained from another as holding ‘tour’ knowledge, whereas the traditional student with archives of experience has a ‘map’ of how higher education works in their head (Gale & Parker, Citation2015) and therefore their choices can be more confident and less constrained. Molla (Citation2021) in his research on overlooked factors of disadvantage using experiences of African refugee youth in Australia, identifies that a key factor in navigational capacity is the provision of relevant and timely information opportunities. Thus, in this paper we take this a central theoretical framework that the framing of information as freely available is problematic due to factors relating to individual navigational capacity, as Molla (Citation2021) explains that ‘putting resources in place is not a sufficient measure of equity as people are differently positioned to transform such opportunities into valued outcomes’ (p. 2).

Moreover, Chapleo (Citation2011) flagged that accessibility of web communication, particularly in newer universities was of importance and the lack of clarity of information was a barrier to UNESCO’s (Citation1998) goals of ‘equity of access’. Burke (Citation2013) writes about the tendency of higher education institutions to internalise the disparities in representation from different groups and align it with discourses of merit-based rewards:

naturalise social inequalities on the premise that the socially ‘fittest’ groups, those who demonstrate certain (socially legitimated) economic and educational success, gained their superior social position and advantage through their evolved ability, intelligence and merit. (p. 111)

Recruitment strategies emphasising diversity … target the social identity pathway through consolidating students’ confidence that the institution offers a social environment where personal and social characteristics are not a threat to personal success. (p. 1026)

Disadvantage is instead positioned as existing in backgrounds, as if somehow disadvantage has been ameliorated for whatever group of people is in question once entering tertiary education. (p. 428)

Answering this call, this research seeks to provide universities with information about barriers to higher education for care-leavers and all non-traditional students. The specific research question of the project is: How easy is it for care leavers to access appropriate ‘cold information’ about higher education entry on institutional websites and what are the problems with current Australian practices?

Methodology

This research seeks to explore the nature of information presented on Australian university websites as it relates to care-leavers. The study used multiple methods, conducted in two phases, comprising content analysis of university websites and semi-structured with practitioners and stakeholders. Although care-leavers were the focus of this research, researchers practiced unobtrusive methods of research (Kellehear, Citation1993) which do not require interviews. When undertaking the research design, we considered the issues about interviewing care-leavers about their information strategies and it was identified that while first person accounts from care-leavers were well canvassed (Harvey et al., Citation2017 Mendes et al., Citation2014; Michell, Citation2012; Michell & Scalzi, Citation2016) there was a significant gap in both what how higher education institutions presented information and also how care-leavers supporters understood the routes to higher education entry.

The content analysis of publicly available information on university websites aims to provide the basis upon which access to information is ascertained for young care leavers seeking to transition to higher education. Content analysis is defined as ‘a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from data to their content’ (Krippendorff, Citation2004, p. 21). It seeks to contextually analyse the symbolic qualities of the content (Krippendorff, Citation1989, p. 403). Anything that occurs in sufficient numbers and has reasonable stable meanings for a specific group of people may be subjected to content analysis. It aims to be systematic and objective, such that all units of analysis receive equal treatment.

The second phase of the research used semi-structured interviews to gain more detailed qualitative data that provides an insight into the way higher education providers perceive and cater for care-experienced prospective students and the supports available for transitioning from care to higher education. May (Citation2001) recommends semi-structured interviews as an interview technique allowing the interviewer to probe participants beyond initial answers and engage them in a conversation managed by the interviewer. The interviewer still uses an interview topic schedule, but has flexibility in the order of questioning and ability to ask follow-up questions (Noakes & Wincup, Citation2004).

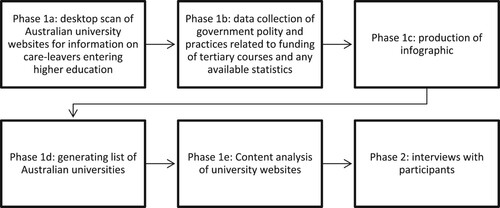

The chronology of our research project is shown in .

Phase 1: Content analysis of university websites

A spreadsheet was used as the main tool for the analysis of university websites. The spreadsheet included column headings for general information such as the university name, the date of the search and the Australian State or territory in which the university is located. Whether or not information was targeted towards different groups was also identified for each university. Forty university websites were scanned for information addressed that would be relevant for care leaving students. Specific identification of information for care-experienced young people was then undertaken. For example, ‘care-leavers’ and parents compared to carers or care providers. The search technique drew on key information areas which had been identified by other work in the sector including Harvey et al. (Citation2017), and from best practice guides in the production of information and literature as well as from the care-leaver researchers who were funded to undertake the search through the authors’ partnership in the project. Employing care-leavers to undertake this research meant that their judgement on whether they believed they had enough information to meet their needs was the basis for the way data was categorised upon collection.

Furthermore, instances where websites specified targeted provision for financial support and funding were identified. This included information regarding scholarships and bursaries for care leavers to facilitate university transitions. Specific information and funding for accommodation was also of particular interest in light of Mendes et al. (Citation2014) insights about the importance of securing suitable accommodation for equity groups whilst studying at university. Furthermore, any mentoring or guidance programmes or additional wellbeing services were also identified and recorded in the spreadsheet. The student life attributes that were selected for searches were based on the attributes identified from the literature on student support (Harvey et al., Citation2017). Lastly, any barriers to university transition for different age groups were identified. This was done by considering the perceptions of university websites from different points of view. For instance, how might a 14-year-old pupil perceive the information presented to them as they plan to transition to university? Similarly, how might an 18-year-old high school graduate perceive the information? Also, it was envisaged how carers undertaking a support role for a young person may perceive the university website’s information. These perspectives were reflected on and recorded in the spreadsheet.

The spreadsheet was filled with information from all the universities. Counts of instances where information was available for care leavers were used to calculate percentages. These percentages highlighted the degree to which information was available for different groups as a proportion of the total websites.

Phase 2: Interviews

The semi-structured interviews were conducted with two cohorts of participants, the first cohort were five representatives from care organisations or professionals employed to provide support and advocacy to care-experienced young people. These interviewees were found from a public search of national organisations supporting young people in care and through associated snowball participation through recommendation of the participants. The participants were asked to identify barriers to accessing university education for out-of-home young people. All those participants in this cohort were given pseudonyms starting with the letter ‘C’.

The second cohort were higher education equity and diversity staff sourced by an open call through the National Association for Equity Practitioners in Higher Education Australasia email network. Institutions that were identified as having good practice in Phase 1 were particularly targeted and followed up for participation in the survey. Further, marketing staff from the institutions where there was information available for OOHC-experienced young people on their sites were recruited. Researchers experienced a good deal of hesitancy to speak on the issue of support OOHC experienced young people in higher education and some significant misunderstandings in the recruitment process where university staff thought the project topic related to students providing care for others or students with disabilities requiring personal care for access to higher education. This cohort ultimately comprised 12 staff from 7 Australian universities employed in marketing, outreach and student equity. The questions they were asked aimed to identify existing knowledge levels of the complex needs of care-experienced people, identify gaps in knowledge, ascertain what admissions support is offered to out-of-home young people, and any existing initiatives to attract them. Participants in this cohort were given pseudonyms starting with the letter ‘H’. Through the course of the project it became clear that some equity practitioners were now based in the marketing departments due to Federal Government initiatives to support higher education participation (e.g. HEPPP funding) and therefore the distinction between staff based in different higher education divisions were not differentiated in analysis or pseudonyms allocated. All participants and their allocated pseudonyms are represented in .

Table 1. Participant log.

The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed and checked by both research assistants and the participants were invited to review their transcripts. Then the transcripts were uploaded to NVivo for analysis. A thematic analysis was undertaken, where the data was coded according to key themes arising from the literature and allowing for new themes to emerge during analysis (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). This analysis resulted in five key findings informing an evidence base from which we have made recommendations to improve admission processes and provide a foundation for policy change to advocate for young people transitioning from care to higher education.

Findings

The project’s interviews with higher education staff, who were involved in equity practice, emphasised the growing importance of attentiveness to the publication of information on university websites:

Universities haven’t changed, for a number of years they [have] seen their websites as the main place to project information. I think the language they use is quite exclusive language, you need to have quite a reasonable level of literacy to be able to understand their words they’re using. Information on the requirements for university. What are the admission processes? You know, it’s not easy to understand. Henry

The website scan highlighted that the majority of the university websites included in this study did not present any information to care-experienced young people about enrolling into university. Specifically, 77 per cent of the 39 university websites displayed no information for such young people. Of the 9 university websites that did include some information, five or 12.8 per cent, were regarded as relevant and included information related to specific support and outreach services such as scholarships, bursaries, student equity programmes and pathways into university courses. Four of the 39 university websites featured information about access and enrolment, but the nature of the information was limited or broad such as notions of ‘support’ without explicitly stating how support would be offered.

One university for instance, required students to contact specialist university equity division for more information. In discussing the presentation and accessibility of information on websites, a participant suggested that there were deficits in understanding in those working on website content development and in recruitment roles:

so from meeting with them, I don’t have this sense that they’re really on top of equity as an issue they are just recruiters, but, um, but they’re not totally insensitive to [equity needs] either. Hattie

In practice, many students are helped by parents and others in the home to understand how these practices work. An interview participant from a higher education institution explained that these issues were hard for institutions: ‘I think that institutions are just totally forgotten that, you know, young people who are in care or leaving care haven’t had any parental influence at all.’ Harold.

Only a quarter of university websites had some available information for parents or carers. ‘Parents’ was the term which was used more prevalently than carers or care providers and guardians was even less frequently used. Most of the information was limited, whereby universities would mention the notion of parents or carers in the context of frequently asked questions or testimonial stories for instance. Four universities had information addressed specifically to carers in relation to accommodation, access programmes and pathways. 25 out of the 39, or Sixty-four per cent of websites did not present any information to carers or parents.

When information was provided to parents or carers, it was presented to both groups simultaneously in a significant number of cases. This is troubling as it is known that parents and carers have different sets of needs. Further, they may be seeking information in very different circumstances concerning their children or care recipient. Using the terms parent and carer or guardian interchangeably overlooks the notion that they are two different groups, which may require different information on topics of varying nature.

Accommodation

Accommodation is a particular problem as state-sponsored care can finish at 18 when students would be starting university. Particularly in jurisdictions where care finishes at 18, our interviewee Charles who worked in the care support sector posed questions about the provision of information and the concomitant responsibilities which come with that provision:

Who are they adults still maintaining in their life? Do they have stable housing. Um, and if things go wrong, uh, what, what is the institution’s responsibility to them? Charles

providing accommodation for young people going to university and other forms of tertiary education and training. Um, so I think on accommodation homelessness, that’s, that’s a pretty clear place where, where universities could make a real significant contribution. Curtis

Funding

The majority, 87 per cent of the 39 university websites, featured information about equity scholarships and bursaries on their websites, but only two, Singleton and Taree University, had information about specific types of funding available for care leavers. The former had six options for scholarships and bursaries applicable to young people with a care experience. The latter had three options: information about the ‘Access Scholarship for students who are care leavers from Australian state or foster care’, a ‘care leaver bursary’, and an initiative specifically for young people who have been involved in the youth justice system.

Most commonly, funding was targeted towards equity groups in the form of scholarships such as low socioeconomic students, Indigenous students, students with a disability and rural and regional located students. Bursaries were less common. Six websites featured information about funding to students experiencing financial hardship, which may be applicable to care leavers. In one case a university displayed information regarding funding for students and euphemised disadvantage as ‘adversely affected by situations out of their control’ Burnie. One of our interviewees, Hector, described the approach to offer support for care-experienced people ‘I think it’s a bit of a scattergun approach from education departments, governments, everyone universities Hector, Bunbury University’.

Information for independent/emancipated young people

Analysing gathered information presented for independent or emancipated young people revealed similar findings to that for care-experienced young people. Most or 87 per cent of the university websites presented no information about university admission for independent or emancipated young people. There was limited information on five institutional websites which addressed the needs of such young people. This information included highlighting university divisions such as student outreach organisations, which could facilitate university enrolment for this group of young people. The onus is on the independent or emancipated student as for care-experienced students to contact the university directly to obtain further information.

Information not for immediate care leavers before finishing school

All of the 39 websites had information for 18-year-olds who may be transitioning to university from high school. In contrast, only 7 website had information for young secondary school studies, such as Year Nine, Ten and Eleven students. Two websites had information for senior secondary care leavers, and three had information regarding outreach programmes for equity group students or programmes designed specifically for outreach to schools with low university attendance rates. 15 had ‘useful’ information for secondary school students in general. These websites included stories from individuals who had successfully transitioned into university. These individuals were often from a diverse range of social and cultural backgrounds. One website featured the story of an Indigenous student, for example. The language was clear and appropriate for communicating to this an older secondary school student age group.

The main potential barrier for secondary school students or those transiting from high school to university was the requirement to contact university staff or organisations for further information. This was the case for four universities where contact information was given for students to obtain further information regarding university enrolment and attendance via phone or email. One website featured a link to a social media account which may facilitate information collection for some, but not necessarily in a confidential way.

Discussion and conclusion

The web search shows that there are significant gaps in when there is information provided which would be useful for care-experienced young people, whether it is useful and useable. While there is some representation of the needs of particular groups, as our participant Hattie says, the websites are mainly promotional tools. Maringe’s (Citation2006) work however, shows us that prospective students do not necessarily see websites as promotional, they class them as informational and therefore the absence of information that is needed can be cast as a significant barrier.

We acknowledge the work of other scholars (e.g. Bluff et al., Citation2012) we regard the lack of university enrolment as product of diverse and significant barriers at the individual and institutional levels to accessing appropriate career information for care-experienced young people. Our position is not that higher education marketing simply enables or prevents care leavers from engaging with universities. Conversely, we argue that these issues cannot be necessarily resolved by any single action, such as university marketing alone, but by a coordinated response from the care sector, tertiary institutions and schools, including managing and disseminating information effectively and appropriately through the system, and with an understanding of the barriers of information retrieval.

This research into the information displayed on university websites found many of the websites that did have information that could help. However many seemed to require some extra sign-posting from career practitioners and guidance in the form of career education about how higher education works. This is not necessarily available in many schools and as our participant Hayden point out, what institution confirmed it is difficult to find in other influencers of care-experienced young people and the individuals have to have been identified to receive the appropriate extra support. This project’s independent review of governmental materials is not much more helpful for care-experienced young people as our public review of websites showed. Only five institutions were found to have easy-to-understand information about the support available for care-experienced young people and only one of these were assessed by the researchers experienced in working with young people with care experience as being easily understandable.

Bunn et al. (Citation2020) explain how although higher education often presents itself as a bastion of social justice and equality it is instead a site for legitimation and reproduction of privilege – in this case a website which re-presents the position that all students may only have standard needs. By not mainstreaming the needs of students who do not have the financial or other resources to understand and access higher education, the public institutional site others these prospective students and reaffirms difference and disadvantage. By not saying anything about care-experienced young people, universities are effectively treating students as the same, which is alienating as Hannah (Citation1999) said: ‘Treating everyone the same can be discriminatory’ (p. 163).

The differential provision of information on the websites and routing of all students to the ‘diversity’ area constructs disadvantage and non-traditional as other and particularly for those students whose needs do not fit into the nationally recognised or most well-known equity groups this is particularly disadvantaging. While there is a move in marketing away from ‘qualifying language’ in the general materials of course promotions, any extra financial or other support is very eligibility criteria framed and higher education marketing has shifted highly marketised messaging in their promotions (Knight, Citation2020).

There are intensifying challenges to enrolment, as noted by Archer (Citation2007) many of these are financial and this impacts students leaving care more frequently and intensely than the norm. While Australia has a specific settlement of higher education arrangements, influenced by the Commonwealth and State nature of funding and bifurcation of higher and vocational education (Moodie, Citation2022) the operations of admissions and marketing can provide wider understandings. Marketing materials of institutions could challenge this by putting front and centre the idea that some supports, such as term-time accommodation during studies are possible as signals to support navigational capacity (Gale & Parker, Citation2015) of all prospective students to explain how higher education transition works. This navigational capacity, of having the map in your head of how it all works, enable students to make more risky choices and possible navigate institutional websites with more ease than those without. Currently, as there is so little information offered, it is implied that everyone has access to the same understanding about how higher education works, when this is not the case (Molla, Citation2021). This change of thinking is the most important contribution this research can make to policy and practice – that marketing professionals in higher education should think of not just the frequent student experience but also take note of what assumptions made about students’ lives may be signalling to all students.

In practical terms understanding that all students may be impacted by specific needs aligns with recommendations made by the project this article is based on. A main suggestion exhorted higher education institutions to move beyond personal categorisations of need and instead to recognise intersectional nature of disadvantage and to support needs-based approach. This could look like thinking about the whole student experience and how individuals could engage with and access all elements of living and surviving as a student and engaging with student life.

Although the accommodation need originates from a particular set of circumstances – e.g. being in state care – for care-experienced young people leaving care the need is not unique to them. For example, in Australia young people leaving regional and remote places to live in urban settings for tertiary education have a concomitant need for clear, affordable and accessible accommodation. Picking up position that institutions should construct their social and study environment in such a way that there is not a focus on individual characteristics as a barrier to success; this research suggests that individual needs-based responses to characteristics do not always work when not particularly well resourced. Therefore instead of linking support to deficit theorised positions; the higher education institutions could realign their thinking to work on the bases that there are barriers, particularly financial, to each course, subject. Choice as Archer (Citation2007) indicates and that if information about access (financial or otherwise) is routinely offered in the marketing then much ground can be gained.

This research shows that currently the marketing of higher education institutions is failing to be an enabling force for the promotion of student equity, there are limitations and benefits to taking such a tightly focused view on care experienced students. Systemically the goals of marketing for an institution ought to align with stated mission for fair access and career information which is both accessible, meets needs and is inclusive of all people is critical for this. There are real possibilities of public information taking a larger role through well thought out interventions and contributing to prospective students’ navigational capacity (Gale & Parker, Citation2015) development and maintenance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Appadurai, A. (2004). The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. In Rao V. & Walton M. (Eds.), Culture and Public Action (pp. 59–84). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Archer, L. (2007). Diversity, equality and higher education: A critical reflection on the ab/uses of equity discourse within widening participation. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(5–6), 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510701595325

- Atkinson, C., & Hyde, R. (2019). Care leavers’ views about transition: a literature review. Journal of Children’s Services, 14(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-05-2018-0013

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Child Protection. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/child-protection

- Bennett, D., Knight, E., Divan, A., Kuchel, L., Horn, J., van Reyk, D., & Burke da Silva, K. (2017). How do research-intensive universities portray employability strategies? A review of their websites. Australian Journal of Career Development, 26(2), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416217714475

- Bluff, B., King, N., & McMahon, G. (2012). A phenomenological approach to care leavers’ transition to higher education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 952–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.020

- Bunn, M., Threadgold, S., & Burke, P. J. (2020). Class in Australian higher education: The university as a site of social reproduction. Journal of Sociology, 56(3), 422–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319851188

- Burke, P. J. (2013). The right to higher education: Beyond widening participation. Taylor and Francis.

- Chapleo, C. (2011). Exploring rationales for branding a university: Should we be seeking to measure branding in UK universities? Journal of Brand Management, 18(6), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2010.53

- Davis, L. A., Wolniak, G. C., George, C. E., & Nelson, G. R. (2019). Demystifying tuition? A content analysis of the information quality of public college and university websites. AERA Open, 5(3), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419867650

- de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. (S. Rendall, Trans.). University of California Press.

- Divan, A., Knight, E., Bennett, D., & Bell, K. (2019). Marketing graduate employability: Understanding the tensions between institutional practice and external messaging. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 41(5), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1652427

- Drew, C. (2013). Elitism for sale: Promoting the elite school online in the competitive educational marketplace. Australian Journal of Education, 57(2), 174–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944113485838

- Evans, C., Rees, G., Taylor, C., & Wright, C. (2019). ‘Widening Access’ to higher education: the reproduction of university hierarchies through policy enactment. Journal of Education Policy, 34(1), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1390165

- Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2015). Calculating student aspiration: Bourdieu, spatiality and the politics of recognition. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2014.988685

- Graham, A., Powell, M. A., Anderson, D., Fitzgerald, R., & Taylor, N. J. (2013). Ethical research involving children. UNICEF Office of Research-Incentives.

- Hannah, J. (1999). Refugee students at college and university: Improving access and support. International Review of Education/Internationale Zeitschrift fr Erziehungswissenschaft/ Revue Inter, 45(2), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003640924265

- Harvey, A., Campbell, P., Andrewartha, L., Wilson, J., & Goodwin-Burns, P. (2017). Recruiting and supporting care leavers in Australian higher education: Report for the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. Centre for Higher Education Equity and Diversity Research, La Trobe University.

- Harvey, A., McNamara, P., Andrewartha, L., & Luckman, M. (2015). Out of care, into university: Raising higher education access and achievement of care leavers. LaTrobe University.

- Ihme, T. A., Sonnenberg, K., Barbarino, M. L., Fisseler, B., & Stürmer, S. (2016). How university websites’ emphasis on age diversity influences prospective students’ perception of person-organization fit and student recruitment. Research in Higher Education, 57(8), 1010–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-016-9415-1

- Jackson, S., & Cameron, C. (2012). Leaving care: Looking ahead and aiming higher. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(6), 1107–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.041

- Jackson, S., Quigley, M., & Ajayi, S. (2003). By degrees: The first year. Hachette.

- Kellehear, A. (1993). Unobtrusive research in the health social sciences. Annual Review of Health Social Science, 3(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.1993.3.1.46

- Knight, E. (2019). Massification, marketisation and loss of differentiation in pre-entry marketing materials in UK higher education. Social Sciences, 8(11), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110304

- Knight, E, & Colvin, E. (2021). Supporting Care Experienced Young People into Higher Education. Collier Fund 4 Report. https://vuir.vu.edu.au/41841/1/Final%20published

- Knight, E. B. (2020). The homogenisation of prospectuses over the period of massification in the UK. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–18.

- Krippendorff, K. (1989). Content analysis. In E. Barnouw, G. Gerbner, W. T. L. Schramm, & L. Gross (Eds.), International encyclopaedia of communication (pp. 403–407). Oxford University Press. http://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/226

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (2nd Ed.). Sage Publication.

- Lewin-Jones, J. (2019). Discourses of ‘internationalisation’: A multimodal critical discourse analysis of university marketing webpages. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 24(2–3), 208–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2019.1596418

- Lomax-Smith, J., Watson, L., & Webster, B. (2011). Higher education base funding review: Final report. Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR).

- Luzeckyj, A. (2009). Are the changing discourses of lifelong learning and student-centred learning relevant to considerations of the first year experience as foundation?

- Maringe, F. (2006). University and course choice: Implications for positioning, recruitment and marketing. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(6), 112–145.

- May, T. (2001). Social research: Issues, methods and process. Open University Press.

- McCaig, C. (2018). System differentiation in England: The imposition of supply and demand. In C. McCaig, J. Hughes, & M. Bowl (Eds.), Equality and differentiation in marketised higher education (pp. 73–93). Palgrave Macmillan.

- McDowall, J. J. (2020). Transitioning to adulthood from our-of-home care: Independence or interdependence? CREATE Foundation.

- McNamara, P., Harvey, A., & Andrewartha, L. (2019). Passports out of poverty: Raising access to higher education for care leavers in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review, 97, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.07.015

- Mendes, P., Michell, D., Wilson, J. Z., & Sanders, R. (2014). Young people transitioning from out-of-home care and access to higher education: A critical review of the literature. Children Australia, 39(4), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2014.25

- Michell, D. (2012). A suddenly desirable demographic?: Care leavers in higher education. Developing Practice: The Child, Youth and Family Work Journal, 33, 44–58.

- Michell, D., & Scalzi, C. (2016). I want to be someone, I want to make a difference: Young care leavers preparing for the future in South Australia. In P. Mendes & P. Snow (Eds.), Young people transitioning from out-of-home care (pp. 115–133). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Molla, T. (2021). Refugee education: homogenized policy provisions and overlooked factors of disadvantage. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 902–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2021.1948892

- Moodie, G. (2022). A typology of tertiary education systems. In E. Knight, A.-M. Bathmaker, G. Moodie, K. Orr, S. Webb, & L. Wheelahan (Eds.), Equity and access to high skills through higher vocational education (pp. 241–267). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84502-5_12

- Morley, L., & Lugg, R. (2009). Mapping meritocracy: Intersecting gender, poverty and higher educational opportunity structures. Higher Education Policy, 22(1), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2008.26

- Morphew, C. C., Fumasoli, T., & Stensaker, B. (2018). Changing missions? How the strategic plans of research-intensive universities in Northern Europe and North America balance competing identities. Studies in Higher Education, 43(6), 1074–1088. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1214697

- Munro, M. (2018). The complicity of digital technologies in the marketisation of UK higher education: exploring the implications of a critical discourse analysis of thirteen national digital teaching and learning strategies. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0093-2

- Noakes, L., & Wincup, E. (2004). Criminological research understanding qualitative methods. Sage.

- Norton, A. (2012). Graduate winners: Assessing the public and private benefits of higher education. Grattan Institute.

- Pollard, L. (2018). Remote student university success: An analysis of policy and practice. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Curtin University.

- Reay, D., Davies, J., David, M., & Ball, S. J. (2001). Choices of degree or degrees of choice? Class, race and the higher education choice process. Sociology, 35(4), 855–874.

- Saichaie, K., & Morphew, C. C. (2014). What college and university websites reveal about the purposes of higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(4), 499–530. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2014.0024

- Stensaker, B., Lee, J. J., Rhoades, G., Ghosh, S., Castiello-Gutiérrez, S., Vance, H., Çalıkoğlu, A., Kramer, V., Liu, S., Marei, M. S., O’Toole, L., Pavlyutkin, I., & Peel, C. (2019). Stratified university strategies: The shaping of institutional legitimacy in a global perspective. The Journal of Higher Education, 90(4), 539–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1513306

- Strauss, A, & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: Sage Publications.

- Tilbury, C., Buys, N., & Creed, P. (2009). Perspectives of young people in care about their school-to-work transition. Australian Social Work, 62(4), 476–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070903312849

- Unesco (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). (1998). World declaration on higher education for the twenty-first century: Vision and action, Adopted at the World Conference on Higher Education, Paris, October 1998.

- Wilson, J. Z., & Golding, F. (2016). Latent scrutiny: Personal archives as perpetual mementos of the official gaze. Archival Science, 16(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-015-9255-3

- Wu, T., & Naidoo, V. (2016). The role of international marketing in higher education (Eds). International marketing of higher education. (pp. 3–9). Palgrave Macmillan, New York.