Abstract

In this editorial, we introduce the special issue on measurement in selling and sales management research. We discuss a number of interesting developments in recent measurement theory of importance to sales researchers and bring together a set of key considerations that we believe researchers need to consider. Following this, we summarize the articles submitted to the special issue.

Given the importance of methods to all academic research, we are very pleased to present you with this special issue of the Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management on “Measurement in Sales Research.” We were delighted to be invited to edit this special issue because we feel measurement plays a critical, yet at present somewhat underappreciated, role in the creation of useful knowledge in selling and sales management. Without strong links between the concepts in our theories, and the empirical data we claim to be measures of those concepts, our conclusions are meaningless. It is our view that the zenith of attention received by measurement in the sales (and marketing) literature was quite some time ago, and since then, measurement issues have perhaps been considered by scholars to be resolved and unworthy of further significant attention. We feel this is an incorrect assumption, and measurement remains an active research frontier in itself, as well as within other fields relevant to sales and marketing. New ideas and techniques are emerging, and strong critiques of concepts and methods that are accepted practices in sales and marketing are also evident. Some of these issues will be discussed in the hope of inspiring new research on measurement from sales scholars.

Our goal when editing this issue was to give a forum both for outstanding cutting-edge empirical and theoretical research on measurement in selling and sales management and for excellent empirical investigations of existing or new sales-relevant measures. When considering the large pool of articles that we and the reviewers had to select from to create this special issue, we found a number of very positive signs for sales scholarship. In particular, it is clear that sales scholars remain committed to their ideas around good measurement as a key part of theory testing and knowledge creation. That said, we did notice a lack of variety in the measurement techniques applied in the articles and an absence of conceptual discussions on measurement itself and how best to apply measurement theories in the sales context. All of our articles either took existing established measures and examined them in depth or developed new measures using techniques already well established in the discipline (some of the issues of which are discussed in the following). Thus, while we are pleased with the quality of the individual articles we are presenting here, we cannot help but feel that a broader conversation in sales (and marketing) research is needed around measurement. We hope to begin such a dialog with this editorial, and as such we provide next a brief discussion of a number of key issues around our current accepted measurement practice in sales and marketing research, drawing from the broader literature on measurement itself where necessary.

Issues in current measurement theory and practice

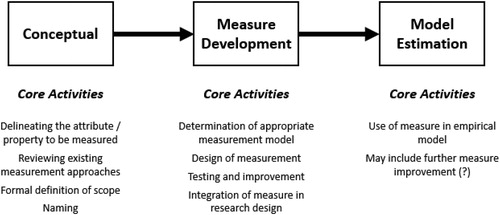

We suggest that the process of developing a new measure for use in a research project looks something like . At the most general level, one must (a) conceptualize what the measure is for, then (b) actually design and test the measure, before (c) using it in an empirical model. If one is using a preexisting measure, one may sometimes enter this process somewhere in the middle, with exactly where being dependent on one’s confidence in the quality of the preexisting measure. Outlining the process in this way allows a number of interesting observations to be made about the treatment of measurement issues in current and past literature of relevance to sales scholars.

First, while there have been many heavily cited articles in the marketing literature written about the specific activities involved in the measure development stage (e.g., Churchill Citation1979; Gerbing and Anderson Citation1988; Rossiter Citation2002), considerably fewer have been written about the conceptual activities involved in measurement (e.g. Lee and Cadogan Citation2016; Mowen and Voss Citation2008). Indeed, about the only area that has received any significant conceptual debate is what is known as the “formative” model (e.g., Cadogan and Lee Citation2013; Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer Citation2001), although as will be discussed later, many scholars do not consider this to be a “measurement” model at all (e.g., Edwards Citation2011; Howell, Breivik, and Wilcox Citation2007; Lee, Cadogan, and Chamberlain Citation2014). Interestingly, this pattern is also observed in the present special issue of JPSSM, with none of our articles primarily focusing on broader conceptual issues around measurement itself. We suggest that there is a need for more research on conceptual issues around measurement in marketing and sales research (and related fields such as psychology and economics). Indeed, there is little variety in the measurement methods used by sales scholars; nor is there substantive reflection on the appropriateness of the models that are used (Rigdon et al. Citation2011). It seems to us that many scholars in sales and marketing assume something akin to “measurement is done” as a topic of study, and that there is little controversy in the field. As such, all they need to do is do what has been done before and cite some precedence.

Second, it is our view that contemporary research in marketing and sales-related fields places too much emphasis on the model estimation step and not enough on measurement in general. This is consistent with the aforementioned dominance of the idea that there is little controversy in measurement anymore, with the focus then turning to other substantive methodological issues. In particular, our experience (and that of our colleagues) suggests that the attention of top-level marketing and sales journal reviewers is – methodologically speaking at least – now focused almost entirely on issues around parameter estimation, and particularly those that may influence causal inference. Yet surely the foundational influence on causal inference is whether the measures of key concepts are of high quality. Unfortunately, an acquaintance with the relevant methodological literature outside sales and marketing might hold quite a few surprises for those who think of “measurement is done” as a topic. Informed by that literature, in what follows, we briefly note a number of possible issues with existing measurement practice in sales-related research, which should serve to help sales scholars orient themselves to important topics in the area.

Conceptual issues: what exactly are we measuring?

Before making any decisions about measurement models or techniques, the most fundamental measurement-related question any researcher must answer is “what am I trying to measure?” This question itself raises a number of key issues, but it also assumes the answers to a number of foundational questions. Most important of these is the issue of exactly what it is that can be measured. Guildford (Citation1954, 3) stated that “whatever exists in some amount can be measured,” which in turn begs the question of what it means for something to exist (Lee and Chamberlain Citation2016). Borsboom (Citation2005) suggested that the only plausible answer to this question is based on the realist philosophical position, which assumes the existence of real attributes, which may or may not be observable, which then cause variation in measuring devices. The causal effect thus flows from the attribute to the measure (Markus and Borsboom Citation2013).

However, simply appealing to what Lee and Cadogan (Citation2016, 1963) termed “blanket realism” does not in itself provide a strong solution on closer inspection. One key issue regards the criteria that should be used to ascribe “reality” to any given unobservable attribute (Chakravartty Citation2015). Unfortunately, Lee and Cadogan (Citation2016) noted that it is difficult to find substantive discussion in recent social science (and by extension sales and marketing) literature on criteria that could be used by researchers to make decisions on how justifiable it is to claim the reality of unobservable attributes in models. One attempt at this is provided by Cadogan, Lee, and Chamberlain (Citation2013, 47), who define two questions that researchers could use when considering how convincing the “existence proposition” is for the attributes1 in their models:

Is it easy to define some “class” of attribute it may belong to? For example, could you call it a type of “attitude,” “perception,” “emotion’” “elementary particle,” and so forth? And, could this theoretical attribute exist if a researcher had not first conceptualized it?

Is it easy to define the theoretical attribute in a way that does not involve it as some combination of other more fundamental components? Pragmatically, can you define it in a way that does not imply, for example, certain observable items, or subdimensions?

That said, while these questions provide a starting point, there is a long way to go before sales and marketing research can come close to convincing claims as to the reality of many of the attributes used in its models. For example, Bagozzi and Lee (Citation2019) showed how challenging it is to conceive and test claims regarding the independent reality of psychological attributes such as emotions. How difficult will it be to provide convincing claims as to the reality of social constructs such as power or organizational concepts such as market orientation?

Taking a realist position on unobservable attributes also illuminates a number of common conceptual misunderstandings about the actual process of measurement often used in sales and marketing research, most particularly the use of multiple items to measure a single attribute. These multiple items are assumed to have a common cause of the attribute of interest, and thus the items are reflective indicators of the attribute (the attribute causes variation in the measure). It is commonly considered that one should use the multiple items to “capture the breadth” or “capture all facets” of the conceptual definition of a construct. However, this is in fact a misunderstanding of the central idea of multiple-item reflective measurement from a realist perspective. The clearest statement of this is by Edwards (Citation2011, 374), who stated: “Reflective measures [i.e., items] are assumed to represent a single dimension [i.e., attribute], such that the measures describe the same underlying construct, and each measure is designed to capture the construct in its entirety… Because they describe the same dimension, reflective measures are conceptually interchangeable, and removing any one of the measures would not alter the meaning or interpretation of the construct.” Thus, it is conceptually impossible for individual items in a multi-item reflective scale to each measure “different facets” of the underlying attribute. Indeed, from the perspective of realism as discussed, the attribute should not have different facets, it should have a singular meaning (Lee and Cadogan Citation2016).

Given the preceding discussion, what then should we make of some common practices in sales and marketing research? Consider first the idea of “multidimensional constructs” (sometimes called “higher-order factors”). The logic behind these constructions is invariably that the individual “dimensions” of each capture unique aspects of some kind of overarching (or “higher-order”) construct. However, in light of the preceding, this does not make sense under a reflective model, and it is more likely that each of the individual dimensions would be better treated as a unique singular attribute itself (see also Lee and Cadogan Citation2013). Researchers also appeal to what is known as the “formative” model in many cases. Formative models are inherently multidimensional in that they bring together multiple measures in a single construction, the meaning of which is defined by the collection of measures. Removing one of the measures in essence removes a part of the meaning of the construct (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer Citation2001). However, numerous authors have pointed out that this means that the formed construct has no meaning apart from being a combination of the measures (e.g., Lee, Cadogan, and Chamberlain Citation2014; Edwards Citation2011; Howell, Breivik, and Wilcox 2008; Markus and Borsboom 2014). While such formative constructs may still perform useful summative functions, it is important not to mistake this for “measuring” some unobserved attribute (Cadogan, Lee, and Chamberlain Citation2013).

Technical issues: is our current measurement practice fit for purpose?

The conceptual concerns discussed center around what it actually means to be measuring something and, by extension, what the things we are trying to measure actually are. However, apart from these more metaphysical ideas, recent developments have raised some issues for a number of empirical measurement practices that are common in sales and marketing research.

The first issue concerns the increase in use of secondary data sources (for example from company databases), sometimes of extremely large scale. Obviously, there are some advantages to using such data sources. However, when one uses secondary data, one is naturally bound by the data that has been collected by others, usually for some other purpose. Researchers need to take care that they do not inappropriately “stretch” the meaning of variables in these data sets, to claim they are measuring something that they are not. Sociological researchers have long been aware of such issues, given the necessity of dealing with large secondary data sources such as national census data (e.g., Blalock Citation1963). In this context, a given variable in a data set might be considered to “measure” different things by different researchers. For example, does quarterly revenue generated by a salesperson measure their performance, their sales skills, or their territory potential? Does the number of calls a salesperson makes in a day (e.g., as collated on a company CRM system) measure their effort or something else? One could think of a multitude of other attributes such variables could measure, if one thought long enough and had a good enough reason to do so. This does raise issues for research consistency and the cumulative building of knowledge.

Interestingly, Hayduk and Littvay (Citation2012) suggested that one could actually change the meaning of what is being measured by changing the amount of error one assumes the measure has, which brings us to the concept of error in measurement. All measures have some greater or lesser amount of error, and it is important that researchers remain cognizant of this. In particular, the use of the term “objective” to refer to some types of data rather than others is a potentially dangerous development in this regard. Even if one has access to (for example) company databases of performance, there remains some error in those measurements. The researcher may choose to ignore that error of course, but this should be an active decision to do so, with good justification, rather than one based on the notion that simply because the data were not measured by a survey of salespeople, it is somehow “objective” and thus without error. It is important that researchers do not forget the importance of measure assessment, even if they are using large-scale company databases and/or other so-called objective data. Further, no matter how sophisticated the estimation technique, the results are meaningless without good measures. Certainly in the past, techniques such as structural equation modeling were inherently bound up with measure assessment. However, in more recent years, estimation and modeling techniques have moved on. One consequence of this is that measure assessment appears to receive less attention than estimation of causal effects. This is unfortunate in our view, and we would encourage researchers to remember the central importance of measurement to the validity of their conclusions.

The final issue we would raise concerns the inherent nature of the measure development and assessment process, in light of recent concerns about the lack of replicability of many research findings (e.g., Open Science Collaboration Citation2015). In particular, a number of researchers have raised awareness of the dangers of inadvertently (or deliberately) overfitting models to data, due to, for example, multiple testing on the same data set (Gelman and Loken 2013; John, Loewenstein, and Prelec Citation2012; Nosek, Spies, and Motyl Citation2012; Simmons, Nelson, and Simonsohn Citation2011). However, inherent to the measure assessment process many sales and marketing researchers were taught is the need to modify measures according to the results of factor analysis, coefficient alpha analysis, and other such techniques (e.g., Churchill Citation1979). If one then tests a substantive theory on the same data set, does this invalidate the conclusions? Certainly, most of us are aware of the need in an ideal world to collect a separate data set for developing a new measure and then to collect a new set to test a theoretical model based on that data (although it is debatable how many of us actually do this). However, what about the case where one is assessing a set of preexisting measures? If one modifies those measures on the basis of the results from measure assessment analysis, and then uses the data to test the theory, is this permissible? Does this have an effect on the likelihood of false positives? These are issues that are yet to be addressed anywhere, to the best of our knowledge, and yet the process of measure development and assessment in sales and marketing is founded on what essentially amounts to the repeated analysis of the same data set.

The articles in this issue

As mentioned earlier, the articles that were submitted to this special issue tended to focus on either developing new measures using well-established techniques and models or deeply evaluating existing popular measures. Each of the articles published in this issue offers important insight into its chosen topic and deserves to be read and used by future researchers. Interestingly, the articles in this issue follow two general themes: adaptive selling and sales force management. As such, it can be seen that what might be called an “individual difference” approach dominates, and we saw little attention given to broader organizational or social measurement. This is understandable given the typical microlevel concepts and theories examined by many sales researchers, but it is worth noting that models of measurement that may work well in measuring individual differences may not directly transfer to measuring broader organizational and social-level concepts.

Adaptive selling: We were particularly interested in the submission of so many articles on the single concept of adaptive selling, which speaks to both the contribution of the original idea of adaptive selling (but also the potential controversies over the concept itself) and its operationalization. While significant work has stemmed from the seminal works on adaptive selling (Spiro and Weitz Citation1990; Weitz Citation1978; Weitz, Sujan, and Sujan Citation1986), the articles in this issue address key conceptual and measurement questions of this stream of research and move the field significantly forward.

First, McFarland disentangles the adaptive selling framework into micro- (i.e., adaptive selling process) and macrolevel (i.e., global construct) adaptive selling. By contrasting the micro- versus macrolevel theories, this article provides the sales literature with a clearer conceptualization of adaptive selling, overview of the ADAPTs measure, and summary of ISTEA (impression, strategy, transmission, evaluation, and adjustment) model, including related theories and outcomes. An important contribution of McFarland’s article is a roadmap for future research on adaptive selling, particularly on the microlevel view (i.e., ISTEA model).

Second, Gabler et al. take a deeper dive into how salespeople form impressions of their customers. They find that salesperson interpersonal mentalizing (IM) skills are critical to sales performance by impacting salesperson self-efficacy and adaptive selling ability. This work helps highlight the importance of impression formation of the microlevel view of adaptive selling.

Third, McFarland and Dixon provide a thorough investigation of salesperson selling behaviors and influence tactics. The authors improved prior definitions and measurement of sales influence tactics and, as a result, provide researchers with enriched conceptualizations and measures. Further, they found an additional influence tactic, personal appeals, that was missing from prior research.

Fourth, while much has been written in the academic literature on adaptive selling, Habel, Alavi, and Linsenmayer take an interesting and needed perspective on the topic – what do practitioners think about adaptive selling and its measurement? The authors lay the foundation for improvements to measuring adaptive selling so that it aligns with practice.

Sales-force management: We received a series of measurement articles dealing with aspects of sales-force management covering various stakeholders of the sales force. To develop a logical coherence to these submissions, we present them in an order that runs from the salesperson up to the manager.

First, given the recent series of sales research involving how a salesperson’s peers (e.g., other salespeople) influence the salesperson’s behaviors, emotions, and performance, Atefi and Pourmasoudi provide a thorough review of past literature, common problems facing researchers, and strategies of measuring peer effects in sales. This article is a great starting point for any peer-related research.

Second, Edmonton, Matthews, and Ambrose also provide a review of an important sales-force topic, salesperson emotional exhaustion. In their meta-analysis, the authors find that emotional exhaustion impacts on turnover intentions, job satisfaction, and role ambiguity are significantly stronger than indicated by prior meta-analytic research (Lee and Ashforth Citation1996). For practice, the article offers strategies and tactics that managers and firms can use to reduce salesperson emotional exhaustion.

Third, building off the previous article on emotional exhaustion, Rutherford, Boles, and Ambrose take a new perceptive on measuring salesperson job satisfaction. The authors examine the 95-item INDSALES scale to find a reliable, shortened version that academia and practice can utilize. Through their investigation, the authors reduced the INDSALES scale to 21 items, three items for each dimension of job satisfaction – pay, promotion, work, customers, supervision, policy, and coworkers.

Finally, Nguyen et al. close out this special issue with their development of a scale on effective sales coaching. Through in-depth interviews and input from almost 10,000 B2B salespeople, the authors find effective coaching involves three facets: adaptability, involvement, and rapport. As managers play an integral role in salespeople’s effectiveness, this research should help springboard research on how to improve sales manager coaching.

Conclusion

It was an honor assembling the articles and working with both the review team and authors for this special issue. Again, the purpose of this special issue was to highlight the importance of measurement in sales and provide researchers a platform to create, update, and review important measurement issues. Reflecting on the process, we are overjoyed about the quality of work as well as the evident passion for measurement in sales.

We offer these last thoughts, drawn from the submissions to this issue. First, we hope the academic community sees the value for more review and meta-analysis research. As is evident in this special issue, the thorough reviews of adaptive selling, influence tactics, peer effects, and so on provide the research community with a unified foundation to conduct research as well as offer road maps for future research. Second, there are still many unresolved measurement issues regarding adaptive selling and other contingent sales processes. Third, we encourage more rigor around content and construct validity. That is, researchers should consider whether the measures they are using and developing align with the business community and business practices and, if not, what implications this has for the attribute they are claiming to measure. Last, most of the work submitted for this issue focused on individual differences. Echoing Cron’s (Citation2017) previous call, we feel that significantly more research, particularly in measurement, should focus on macrolevel sales issues. We hope you enjoy the issue.

Notes

1 Cadogan, Lee & Chamberlain (Citation2013) used the term “entity” in their discussion, rather than “attribute” as used herein. However, on reflection, “entity” is probably not the appropriate term for the idea they are discussing. Specifically, an “entity” that exists would have “attributes” that could be measured, but one does not specifically measure the “entity” itself (other than detecting its presence or absence). As such, we reword their statements to replace “entity” with “attribute.” This is an ongoing discussion within philosophy of science, however, and we can only scratch the surface here.

References

- Bagozzi, Richard P., and Nick Lee. 2019. “Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience in Organizational Research: Functional and Nonfunctional Approaches.” Organizational Research Methods 22 (1):299–331. doi: 10.1177/1094428117697042.

- Blalock, Hubert M. 1963. “Making Causal Inferences for Unmeasured Variables from Correlations among Indicators.” American Journal of Sociology 69 (1):53–62. doi: 10.1086/223510.

- Borsboom, Denny. 2005. Measuring the Mind. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

- Cadogan, John W., and Nick Lee. 2013. “Improper Use of Endogenous Formative Variables.” Journal of Business Research 66 (2):233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.006.

- Cadogan, John W., Nick Lee, and Laura Chamberlain. 2013. “Formative Variables Are Unreal Variables: Why the Formative MIMIC Model Is Invalid.” AMS Review 3 (1):38–49. doi: 10.1007/s13162-013-0038-9.

- Chakravartty, Anjan. 2015. “Scientific Realism.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. N. Zalta, Fall 2015 edition. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2015/entries/scientific-realism/.

- Churchill Jr., Gilbert A. 1979. “A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs.” Journal of Marketing Research 16 (1):64–73. doi: 10.2307/3150876.

- Churchill Jr., Gilbert A. 1992. “Special Section on Scaling and Measurement: Better Measurement Practices Are Critical to Better Understanding of Sales Management Issues.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 12 (2):73–80.

- Cron, William L. 2017. “Macro Sales Force Research.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 37 (3):188–197. doi: 10.1080/08853134.2017.1352449.

- Diamantopoulos, Adamantios, and Heidi M. Winklhofer. 2001. “Index Construction with Formative Indicators: An Alternative to Scale Development.” Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2):269–277. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.38.2.269.18845.

- Edwards, Jeffrey R. 2011. “The Fallacy of Formative Measurement.” Organizational Research Methods 14 (2):370–388. doi: 10.1177/1094428110378369.

- Gelman, Andrew, and Eric Loken. 2013. The Garden of Forking Paths: Why Multiple Comparisons Can Be a Problem, Even When There Is No “Fishing Expedition” or “p-Hacking” and the Research Hypothesis Was Posited Ahead of Time. Department of Statistics, Columbia University, New York.

- Gerbing, David W., and James C. Anderson. 1988. “An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment.” Journal of Marketing Research 25 (2):186–192. doi: 10.2307/3172650.

- Guildford, Joy P. 1954. Psychometric Methods, Rev. ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Hayduk, Leslie A., and Levente Littvay. 2012. “Should Researchers Use Single Indicators, Best Indicators, or Multiple Indicators in Structural Equation Models?” BMC Medical Research Methodology 12 (1):159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-159.

- Howell, Roy D., Einar Breivik, and James B. Wilcox. 2007. “Is Formative Measurement Really Measurement? Reply to Bollen (2007) and Bagozzi (2007).” Psychological Methods 12 (2):238–245. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.238.

- John, Leslie K., George Loewenstein, and Drazen Prelec. 2012. “Measuring the Prevalence of Questionable Research Practices with Incentives for Truth Telling.” Psychological Science 23 (5):524–532. doi: 10.1177/0956797611430953.

- Lee, Nick, and John W. Cadogan. 2013. “Problems with Formative and Higher-Order Reflective Variables.” Journal of Business Research 66 (2):242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.004.

- Lee, Nick, and John Cadogan. 2016. “Welcome to the Desert of the Real: Reality, Realism, Measurement, and C-OAR-SE.” European Journal of Marketing 50 (11):1959–1968. doi: 10.1108/EJM-10-2016-0549.

- Lee, Nick, and Laura Chamberlain. 2016. “Pride and Prejudice and Causal Indicators.” Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives 14 (3):105–109. doi: 10.1080/15366367.2016.1227681.

- Lee, Nick, John W. Cadogan, and Laura Chamberlain. 2014. “Material and Efficient Cause Interpretations of the Formative Model: Resolving Misunderstandings and Clarifying Conceptual Language.” AMS Review 4 (1–2):32–43. doi: 10.1007/s13162-013-0058-5.

- Lee, Raymond T., and Blake E. Ashforth. 1996. “A Meta-Analytic Examination of the Correlates of the Three Dimensions of Job Burnout.” Journal of Applied Psychology 81 (2):123–133. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.81.2.123.

- Markus, Keith A. and Denny Borsboom. 2013. Frontiers of Test Validity Theory. New York, NY: Routledge

- Mowen, John C., and Kevin E. Voss. 2008. “On Building Better Construct Measures: Implications of a General Hierarchical Model.” Psychology and Marketing 25 (6):485–505. doi: 10.1002/mar.20221.

- Nosek, Brian A., Jeffrey R. Spies, and Matt Motyl. 2012. “Scientific Utopia: II. Restructuring Incentives and Practices to Promote Truth over Publishability.” Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 7 (6):615–631. doi: 10.1177/1745691612459058.

- Open Science Collaboration 2015. “Estimating the Reproducibility of Psychological Science.” Science 349 (6251):aac4716.

- Rigdon, Edward E., Kristopher J. Preacher, Nick Lee, Roy D. Howell, George R. Franke, and Denny Borsboom. 2011. “Avoiding Measurement Dogma: A Response to Rossiter.” European Journal of Marketing 45 (11/12):1589–1600. doi: 10.1108/03090561111167306.

- Rossiter, John R. 2002. “The C-OAR-SE Procedure for Scale Development in Marketing.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 19 (4):305–335. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8116(02)00097-6.

- Simmons, Joseph P., Leif D. Nelson, and Uri Simonsohn. 2011. “False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant.” Psychological Science 22 (11):1359–1366.

- Spiro, Rosann L., and Barton A. Weitz. 1990. “Adaptive Selling: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Nomological Validity.” Journal of Marketing Research 27 (1):61–69. February, doi: 10.2307/3172551.

- Weitz, Barton A. 1978. “Relationship between Salesperson Performance and Understanding of Customer Decision-Making.” Journal of Marketing Research 15 (4):501–516. doi: 10.1177/002224377801500401.

- Weitz, Barton A., Harish Sujan, and Mita Sujan. 1986. “Knowledge, Motivation, and Adaptive Behavior: A Framework for Improving Selling Effectiveness.” Journal of Marketing 50 (4):174–191. doi: 10.2307/1251294.