Abstract

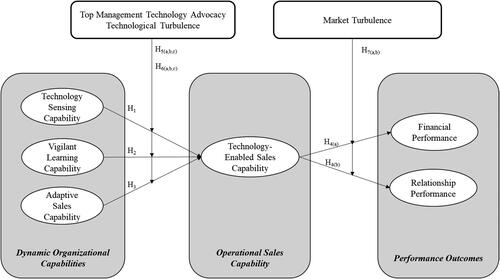

As organizations emerge from the disruptions induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is becoming evident that the sales function has shifted irrevocably toward increased reliance on technological resources to facilitate inherent processes and activities. Integrating research from the dynamic capabilities and sales capabilities literature, this study examines why some organizations are more adept than others at harnessing and leveraging emergent technological resources to enhance sales operations. Specifically, we develop and test a theoretical framework of the antecedents and consequences of technology-enabled sales capability, a firm-level operational capability that captures the embeddedness of technology in sales processes and activities. The framework proposes that three firm-level dynamic capabilities—technology-sensing capability, vigilant market learning capability, and adaptive sales capability—are positively related to technology-enabled sales capability, which in turn is positively related to financial performance and customer relationship performance. The framework also explores the moderating effects of top management technology advocacy and two environmental variables—technological and market turbulence—on the development and deployment of technology-enabled sales capability. Based on findings from data gathered from 224 business-to-business sales managers, we extend theoretical and managerial contributions and provide directions for future research.

Over the past two decades, the rapid emergence of technologies for enabling and enhancing sales force routines and processes has been one of the most significant trends in the sales environment (Guenzi and Habel Citation2020; Hunter and Perreault Citation2007; Rayburn et al. Citation2021). Although investments in sales technologies have been steadily increasing over the years, especially as organizations transitioned into the age of sales digitalization and artificial intelligence (Singh et al. Citation2019), the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the pursuit of technological solutions for transforming sales operations (Hartmann and Lussier Citation2020; Rangarajan et al. Citation2021). Initially, the widespread infusion of technology within the sales function was regarded as a crisis response to the pandemic; however, it is now becoming apparent that organizations are likely to persist with technology-enabled sales operations even in the post-pandemic “new normal.” For instance, a recent report by McKinsey & Company attests that technology-enabled sales will be a persistent change stemming from the pandemic and that top managers in sales organizations regard it to be equally or even more effective than pre-pandemic sales practices (Bages-Amat et al. Citation2020). Likewise, it has also been noted that the pandemic has created enduring shifts in the interaction and purchase preferences of business-to-business customers, forcing organizations to explore technological tools and solutions that support the sales process, customer engagement, and go-to-market strategies (Rangarajan et al. Citation2021).

Consequently, for organizations to be competitive in the post-pandemic era, it has become imperative to manage technological resources that enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of sales operations and, ultimately, secure positional advantages (Mattila, Yrjölä, and Hautamäki Citation2021; Rangarajan et al. Citation2021; Zoltners et al. Citation2021). Yet, as the 2020–2021 State of Sales Report released by the CRM platform organization, Pipedrive, points out, although sales professionals who received appropriate technological tools and resources reported greater levels of job performance, job satisfaction, and quota attainment than others, a majority of respondents also disclosed that their companies are yet to identify or implement the right technological tools to support sales activities. These trends lead to the hitherto unaddressed research question: why are some firms better than others in harnessing technological resources to enhance sales operations? Accordingly, in this research, we draw attention to the development and deployment of technology-enabled sales capability as a valuable organizational capability focused on empowering the sales function with appropriate technological advancements. Specifically, technology-enabled sales capability is defined as an organization’s ability to leverage technology resources to facilitate or reinforce sales force processes and activities. This conceptualization and level of analysis distinguishes technology-enabled sales capability from seemingly related constructs such as digitalization of selling capabilities (Johnson and Bharadwaj Citation2005) and digital selling (Mullins and Agnihotri Citation2022). Whereas digitalization of selling capabilities focuses on the creation of technological interfaces for customers to engage in self-directed interactions with an organization without the intervention of salespeople, technology-enabled sales capability involves an organization’s ability to empower its sales force with appropriate technologies to perform sales routines and processes. Likewise, whereas digital selling is an individual-level activity subsuming salespeople’s ability to utilize available technological resources, technology-enabled sales capability is an organization-level capability that captures a firm’s ability to adopt and make available a wide array of technologies that support sales operations.

Broadly stated, the purpose of this study is to develop and test a capabilities-based contingency framework of the antecedents and consequences of technology-enabled sales capability. In doing so, we address several gaps in the extant literature. First, although researchers have pointed out that organizational capabilities with respect to managing the sales function are distinct from capabilities possessed by salespeople within the sales function (Cron et al. Citation2014), studies on firm-level capabilities are limited in the sales literature. Barring a few notable exceptions (e.g., Guenzi, Sajtos, and Troilo Citation2016; Johnson and Bharadwaj Citation2005; Krush et al. Citation2013; Siahtiri, O’Cass, and Ngo Citation2014), few studies have explored how organizations differ from their competitors in developing and deploying capabilities pertaining to the sales function. In this regard, technology-enabled sales capability is positioned as an essential firm-level capability that captures how organizations differ in their ability to leverage technological resources that are pertinent for supporting sales operations.

Second, the limited research on firm-level capabilities in the sales literature is somewhat singularly focused on deploying capabilities (e.g., Guenzi et al. Citation2016; Krush et al. Citation2013; Siahtiri et al. Citation2014), with little attention on why organizations differ in the development of such capabilities. Indeed, while researchers have shown that organization-level sales capabilities can engender positive outcomes (e.g., Johnson and Bharadwaj Citation2005; Krush et al. Citation2013), knowledge on how firms could cultivate such capabilities is limited. Given that the success of sales operations in contemporary organizations depends heavily on coordination and collaboration amongst different functional units, it is important to investigate organization-level drivers of sales capabilities and, ultimately, firm performance (Guenzi, Sajtos, and Troilo Citation2016). Correspondingly, we draw from the organizational capabilities literature, which offers insight on how dynamic and adaptive capabilities are instrumental in developing operational capabilities (Day Citation2011), and identify three dynamic capabilities—technology sensing capability, vigilant market learning capability, and adaptive sales capability—as critical drivers of technology-enabled sales capability. Third, studies on technology in the sales context have predominantly focused on two salesperson-level issues: how to promote salespeople to adopt or use technology and how technology use influences their performance (Jelinek Citation2014). While there is considerable research on the antecedents and consequences of technology use by salespeople (e.g., Ahearne et al. Citation2008; Hunter and Perreault Citation2007; Mullins and Agnihotri Citation2022; Schillewaert et al. Citation2005), very little is known regarding how organizations can benefit from their ability to leverage technology in the context of the sales function. Addressing this gap, we propose that technology-enabled sales capability is an important antecedent of a firm’s financial and relational performance.

Fourth, studies in the sales literature are increasingly focusing on understanding the impact of shifts in the internal and external environment on the sales function. For instance, research has explored the contingent effects of top management characteristics (Dishop and Good Citation2022; Krush, Agnihotri, and Trainor Citation2016) as well as environmental turbulence (Guo et al. Citation2018; Hartmann and Lussier Citation2020; Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015) to provide more holistic theoretical frameworks and nuanced explanations of sales phenomena. Similarly, we investigate the moderating effects of an internal environmental factor, top management technology advocacy, and two external environmental variables, namely, technological turbulence and market turbulence, on the relationships involving the antecedents and consequences of technology-enabled sales capability.

In the following sections, we review relevant background literature and develop the proposed framework. Next, we articulate data collection and analysis procedures and present the results of hypotheses tests. Finally, we discuss theoretical and practical contributions as well as study limitations and directions for future research.

Theoretical background

Dynamic capabilities refer to a “firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece et al. Citation1997, 516); whereas, operational capabilities refer to a firm’s ability to “perform an activity on an on-going basis using more or less the same techniques on the same scale to support existing products and services for the same customer population” (Helfat and Winter Citation2011, 1244). When firms possess and leverage dynamic capabilities, they are in a better position to continuously build, integrate, and reconfigure resources and competences for enhancing productivity (Badrinarayanan, Ramachandran, and Madhavaram Citation2019). Particularly, as dynamic capabilities help a firm continuously evolve and reconfigure the resources underlying its operational capabilities to better match the environment (Teece Citation2007), dynamic capabilities theorists (e.g., Eisenhardt and Martin Citation2000; Teece Citation2007) consistently advocate for researchers to model the indirect relationship between dynamic capabilities and performance through different types of functional and operational capabilities.

In this regard, a considerable amount of research has investigated how dynamic capabilities enhance activities of the marketing function and, consequently, firm performance (e.g., Day Citation2011; Krasnikov and Jayachandran Citation2008; Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015). Yet, as can be seen from the literature review in , the impact of firm-level dynamic capabilities on the sales function has received far less attention (Badrinarayanan et al. Citation2019; Menguc and Barker Citation2005; Peterson et al. Citation2021). In fact, as can be seen from , research on firm-level capabilities, in general, is also extremely limited in the sales literature. The few existing studies focus predominantly on the consequences of sales or selling capabilities (e.g., Krush et al. Citation2013; Siahtiri et al. Citation2014), and offer little insight on the antecedents of such capabilities. This lacuna is surprising, considering the extensive evidence on how organizational capabilities contribute to superior performance and competitive advantage (e.g., Kozlenkova, Samaha, and Palmatier Citation2014; Krasnikov and Jayachandran Citation2008; Madhavaram and Hunt Citation2008; Menguc and Auh Citation2006; Vorhies and Morgan Citation2005).

Table 1. Review of research investigating firm-level sales-specific capabilities.

As organizational capabilities are the “glue” that binds resources and optimizes resource deployment for maximum advantage (Day Citation1994), they take on added importance for sustaining firm performance in the midst of disruptions caused by exogenous shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. As Hartmann and Lussier (Citation2020, p. 101) point out, the COVID-19 pandemic brought about severe and persisting “social, technological, and structural changes for many B2B sales forces” that rendered them “vulnerable” and “partially paralyzed.” In this regard, firm-level dynamic capabilities can enable the sales function to be more resilient and responsive to unexpected disruptions by facilitating the reconfiguration of resources that are essential for ongoing sales operations and activities. Against this backdrop, drawing from the foundations of resource-based theory (e.g., Barney Citation1991; Kozlenkova et al. Citation2014), competences/capabilities theory (e.g., Day Citation1994), and dynamic capabilities theory (Makadok Citation2001; Teece Citation2007; Winter Citation2003), we extend current understanding of the relationship between dynamic capabilities and operational capabilities pertaining to the sales function. Specifically, we develop and test a model (see ) that investigates technology-enabled sales capability, an operational capability that merges aspects of technology and sales, as a key mediating variable between three dynamic capabilities (i.e., technology sensing, vigilant market learning, and adaptive sales) and financial and relational performance. Additionally, because recent works advocate for understanding how both organizational and environmental factors influence the relationships between dynamic capabilities and operational capabilities (e.g., Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015), we incorporate top management technology advocacy and two environmental factors (i.e., technological turbulence and market turbulence) as moderators in our model. In doing so, our efforts extend prior research on dynamic capabilities in marketing (Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015) and firm-level sales capabilities (e.g., Guenzi et al. Citation2016; Krush et al. Citation2013; Nijssen, Guenzi, and van der Borgh Citation2017; Töytäri and Rajala Citation2015; Trainor Citation2012). The following sections outline the constructs in our model and their associated hypotheses. We begin by discussing technology-enabled sales capability and the role of the three dynamic capabilities. Then, we discuss how technology-enabled sales capability influences performance outcomes and, subsequently, how top management technology advocacy, technological turbulence, and market turbulence moderate specific relationships in our model.

Hypotheses development

Dynamic capabilities and technology-enabled sales capability

Prior research has emphasized the importance of technology in facilitating sales force effectiveness (e.g., Hunter and Perreault Citation2007; Singh et al. Citation2019; Zoltners et al. Citation2021). Nevertheless, how firms differ in their abilities to leverage available and emergent technology for enhancing sales operations is poorly understood. Within the broader marketing literature, studies (e.g., Moorman and Slotegraaf Citation1999; Saboo, Kumar, and Anand Citation2017; Song, Di Benedetto, and Nason Citation2007; Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015) have largely treated marketing capabilities and technological capabilities as distinct entities (for exception, see Johnson and Bharadwaj Citation2005; Trainor et al. Citation2011; Yadav and Pavlou Citation2020). However, other studies in management and information systems note that technological capabilities can be fully realized only when merged with complementary functional capabilities (e.g., Bhatt and Grover Citation2005; Clemons and Row Citation1991). For instance, Nevo and Wade (Citation2010) make a compelling argument that technology assets can achieve their strategic potential only when they are synergistically combined with other organizational resources to form technology-enabled resources. In line with this notion, Ayabakan et al. (Citation2017) argue that information technology (IT) adds business value when it serves as an input resource for augmenting a firm’s IT-enabled production capability. Similarly, Dong et al. (Citation2009) note that a technology-enabled supply chain capability is critical for supply chain process performance and competitive advantage. Other studies have illustrated the relevance of technology-enabled process integration (Rai et al. Citation2015), new product development (Pavlou and El Sawy Citation2010), infrastructure flexibility (Benitez et al. Citation2018), and strategic flexibility (Tafti et al. Citation2013), among others. Extending this perspective, and consistent with the etymology of the term “enable” (Oxford English Dictionary Citation2020) and research investigating technology-enablement in sales (e.g., Badrinarayanan, Madhavaram, and Granot Citation2011; Johnson and Bharadwaj Citation2005; Shoemaker Citation2001), we define technology-enabled sales capability as a firm’s ability to leverage technology resources to facilitate or reinforce the activities and processes inherent in the sales function.

As per our conceptualization, technology-enabled sales capability (i) refers to the integration of available or emergent technology, in general, rather than the adoption of a specific technology (e.g., salesforce automation) and (ii) reflects that organizations can be more or less effective at using technology to strengthen, support, or make possible the activities involved in the sales process, which can enhance the entire sales function as a whole. Thus, technology-enabled sales capability differs from the broader concept of sales enablement (Peterson et al. Citation2021). For instance, Peterson et al. (Citation2021, p. 543) define sales enablement as “an overarching dynamic capability that aligns varied firm resources to benefit the customer journey and selling productivity.” According to this conceptualization, sales enablement refers to firms’ ability to coordinate a variety of intra-firm resources, including technology, to reinforce the sales process and, thus, technology-enabled sales capability could be construed as an important constituent element of effective sales enablement. Next, we discuss the dynamic capabilities that drive technology-enabled sales capability.

Technology-sensing capability

Srinivasan, Lilien, and Rangaswamy (Citation2002) define technology-sensing as “an organization’s ability to acquire knowledge about and understand new technology development” (p. 48). Firms with a stronger technology-sensing capability are better positioned to take advantage of technological changes in their environment by regularly scanning and searching for technology-related opportunities and threats, both externally and internally (Mikalef, Conboy, and Krogstie Citation2021; Srinivasan et al. Citation2002; Teece Citation2007). Thus, this capability enables firms to continuously explore and exploit technology-related knowledge from diverse sources such as salespeople, inhouse research and development, vendors, customers, and competitors, among others. The constant influx of technology-related knowledge from dynamic environmental scanning creates a climate to respond to environmental change by making targeted investments toward updating technological resources (Srinivasan et al. Citation2002). According to a recent industry survey of 750 business-to-business sales professionals, about 45% of respondents’ organizations have invested in new sales technologies after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, including customer relationship management systems, contract lifetime management systems, performance management and sales analytics software, communication and quote management tools, digital experience interfaces, and customer data platforms among others (DocuSign 2021). Prior studies have found that technology-sensing capability is positively related to the infusion of technology into marketing and customer service functions (e.g., Trainor et al. Citation2011). In a similar vein, as firms with superior technology-sensing capability would have a greater appreciation of the importance of existing and emergent technology for sales force activities, they are expected to be better positioned to actively leverage available technologies within the sales function. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1: A firm’s technology sensing capability is positively related to a firm’s technology-enabled sales capability.

Vigilant market learning capability

Building on the notion of organizational vigilance (e.g., Day and Schoemaker Citation2006), Day (Citation2011) introduced the concept of vigilant market learning, which is at the confluence of market sensing (e.g., Day Citation1994; Morgan, Slotegraaf, and Vorhies Citation2009) and market learning (e.g., Luo, Slotegraaf, and Pan Citation2006; O’Cass and Weerawardena Citation2010). Specifically, vigilant market learning capability is defined as a firm’s ability to continuously scan, search, interpret, and act on changes in customer preferences and competitor behaviors. Due to the dynamic, hypercompetitive nature of the global economy, developing and maintaining vigilant market learning capability is critical for firms if they want to stay ahead of their competition. Indeed, as vigilant market learning capability is a type of proactive, sense-and-respond capability, it can help firms make proactive adjustments to their underlying resource base to match emerging trends in the market (Jayachandran, Hewett, and Kaufman Citation2004). In particular, research has pointed out that, after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, customers are evincing shifts in exchange preferences and are now favoring digital technologies, virtual communication interfaces, online and social media platforms, videos and live chat, and automated channels for interactions with salespeople and sales organizations (Rangarajan et al. Citation2021). Thus, the ability of firms to sense and respond to changes in technological preferences in the market is essential for technology-enabled sales capability because firms with superior vigilant market learning capability will be better able to reconfigure their technology resources and adjust how they leverage technology to better address the expressed and latent needs of current and potential customers (Narver, Slater, and MacLachlan Citation2004). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H2: A firm’s vigilant learning capability is positively related to a firm’s technology-enabled sales capability.

Adaptive sales capability

A common feature underlying dynamic capabilities is a firm’s ability to adapt to changes in the environment, or what some have referred to as adaptive capability (Wang and Ahmed Citation2007). Rindova and Kotha (Citation2001) note that adaptive capabilities enable firms to engage in “continuous morphing” of form, function, offerings, resources, and business models through which they can regenerate competitive advantage under conditions of rapid change. Within the sales domain, scholars mainly investigate the adaptive nature of sales through the adaptive selling behaviors of salespeople (e.g., McFarland Citation2019; Rapp, Agnihotri, and Forbes Citation2008; Spiro and Weitz Citation1990). However, some scholars have recently highlighted the firm’s role in reconfiguring the salesforce's structure, budget, and activities to deal with to pandemic-induced changes in the market (e.g., Gavin et al. Citation2020; Rangarajan et al. Citation2021; Sharma, Rangarajan, and Paesbrugghe Citation2020). Such reconfiguration reflects the emphasis firms place on adapting their resources and organizational form (e.g., sales approach, channels, interaction platforms) to facilitate change and continuity when confronted with significant environmental turbulence (Rindova and Kotha Citation2001). Because our focus is on firm-level capabilities, we draw from the literature on adaptive capabilities (Day Citation2011; Guo et al. Citation2018; Hunt and Madhavaram Citation2020) to define adaptive sales capability as a firm’s ability to alter its sales strategy, sales structure, and/or sales activities in response to buyer characteristics or selling situations.

When confronted with a need to adapt their sales approach, firms reconfigure their resources to better fit their strategic needs. In fact, firms that have higher adaptive sales capability are better able to reconfigure available resources to more closely align with their adapted sales approach. For example, prior to the pandemic, many organizations were already altering their sales approaches by transitioning toward implementing virtual sales teams (Badrinarayanan et al. Citation2011) and/or placing greater emphasis on the role of the inside salesforce (Sleep et al. Citation2020) and hybrid sales structures (Thaichon et al. Citation2018). However, due to the pandemic, most, if not all, organizations had to rapidly transition to a primarily remote sales approach, consisting of virtual sales, inside sales, and/or hybrid sales structures (Bages-Amat et al. Citation2020; Gavin et al. Citation2020). Such structures rely more heavily on technologies, such as videoconferencing and webchat, to conduct sales activities. Thus, when a firm is prompted to adjust their sales strategy, sales structure, and/or sales activities due to changes in the environment (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic), they must also adjust how available technology resources are used within the firm. Accordingly, firms with superior adaptive sales capability are better able to reconfigure their available technology resources and leverage such resources to match the firm’s adapted sales approach. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3: A firm’s adaptive sales capability is positively related to a firm’s technology-enabled sales capability.

Technology-enabled sales capability and performance outcomes

Although capabilities have long been recognized as drivers of firm performance and sources of competitive advantage (e.g., Day Citation1994; Krasnikov and Jayachandran Citation2008; Morgan, Slotegraaf, and Vorhies Citation2009; Morgan, Vorhies, and Mason Citation2009; Vorhies and Morgan Citation2005), there is relatively little research on performance outcomes of firm-level sales capabilities. Some studies have examined the outcomes of variations of sales capabilities on financial and customer performance (e.g.,Guenzi et al. Citation2016; Keszey and Biemans Citation2016; Nijssen et al. Citation2017; Worm et al. Citation2017). Just as with other functional capabilities, technology-enabled sales capability is largely tacit, internalized, distributed, and difficult to imitate, perhaps more so than function agnostic technological capabilities. Thus, the development of technology-enabled sales capability could enable organizations to achieve superior performance standards. Accordingly, we investigate two outcomes of technology-enabled sales capability, financial performance and customer relationship performance.

Financial performance

Research has shown that technology can improve a firm’s ability to prospect potential customers and close sales (Moutot and Bascoul Citation2008), and, in turn, positively influence financial performance. Further, while there is evidence that technology enables salesperson performance (Ahearne, Hughes, and Schillewaert Citation2007), research understanding the financial implications associated with technology enabling the sales function is limited. However, because the impact of technology capabilities on firm performance is well-understood (e.g., Krasnikov and Jayachandran Citation2008; Song et al. Citation2007) and the literature suggests that firms gain competitive advantages from technology when merging technology with complementary resources (Bhatt and Grover Citation2005; Clemons and Row Citation1991), we expect technology-enabled sales capability to be positively related to financial performance. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H4a: A firm’s technology-enabled sales capability is positively related to a firm’s financial performance

Customer performance

Scholars have recognized the importance of technology for enhancing and supporting firms’ customer-relating capabilities (e.g., Jayachandran et al. Citation2005; Trainor et al. Citation2014). Indeed, extant research supports the premise that merging technology resources with sales practices and routines can improve customer acquisition and retention (Ahearne and Rapp Citation2010; Hunt, Arnett, and Madhavaram Citation2006; Rapp, Trainor, and Agnihotri Citation2010). Overall, firm-level technology-enabled capabilities can influence customer relationships. Accordingly, we contend that technology-enabled sales capability enhances customer relationship performance by improving an organization’s ability to effectively and efficiently build and manage customer relationships (Trainor et al. Citation2014). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H4b: A firm’s technology-enabled sales capability is positively related to a firm’s customer relationship performance.

Moderating role of top management technology advocacy

Extensive research has established that a firm’s leadership plays an important role in setting the overall initiatives and priorities for the organization as a whole (Carpenter, Geletkanycz, and Sanders 2004; Hambrick and Mason Citation1984; Menz Citation2012). Indeed, for any strategic initiative to be successful, it requires advocacy and support from top management to establish legitimacy and importance and to allocate the necessary resources for the success of the initiative. In fact, extant literature provides strong evidence that top management support is a critical factor influencing the success of technology implementation and use within the firm (Chatterjee, Chaudhuri, and Vrontis Citation2022; Sabherwal, Jeyaraj, and Chowa Citation2006; Srinivasan et al. Citation2002). Accordingly, we include top management technology advocacy as a moderating variable that influences the relationship between the three dynamic capabilities and technology-enabled sales capability. Top management technology advocacy refers to “the efforts of the top management team to emphasize the importance of organizational responsiveness to new technologies” (Srinivasan et al. Citation2002, 55). Because resource reconfiguration is a central tenet of dynamic capabilities, firms that have superior top management technology advocacy will be better positioned to reconfigure technology resources to enhance how the firm leverages technology for sales purposes.

Technology sensing capability

Top management technology advocacy is critical for convincing the members of an organization of the importance of technology (Speier and Venkatesh Citation2002). Indeed, when technology advocacy is high, executives are more likely to allocate resources toward technology initiatives and emphasize the importance of understanding and applying technology to benefit the firm (Oliveira, Thomas, and Espadanal Citation2014), which has been shown to influence employees’ orientation toward technology (Hunter and Perreault Citation2006). In fact, drawing from the attention-based perspective in management (Ocasio Citation1997; Ren and Guo Citation2011), we contend that top management technology advocacy can influence the relationship between technology sensing capability and technology-enabled sales capability because greater top management technology advocacy directs employees’ limited attention toward identifying and exploiting technology and technology-related opportunities and threats. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H5a: Greater top management technology advocacy amplifies the positive relationship between technology sensing capability and technology-enabled sales capability.

Vigilant market learning capability

Additionally, because top management technology advocacy helps direct employees’ attention toward identifying technology opportunities and threats, firms with greater top management technology advocacy are more effective at anticipating emerging technology-related trends in the market before competitors, which helps reduce technological and market uncertainties (March Citation1991), and, in turn, helps firms proactively respond to technology-related opportunities (Guo et al. Citation2018). Moreover, because vigilant market learning can “be amplified with emerging technologies for seeking patterns in micro data and sharing insights quickly” (Day Citation2011, 188), greater executive commitment to technology can enhance vigilant market learning due to greater resource allocation efforts toward technology initiatives (Sleep, Hulland, and Gooner Citation2019), which “will ready the organization to act ahead of rivals” (Day Citation2011, 189). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H5b: Greater top management technology advocacy amplifies the positive relationship between vigilant learning capability and technology-enabled sales capability.

Adaptive sales capability

Top management technology advocacy can also amplify the effects of adaptive sales capability by providing the necessary leadership and allocating the necessary technology-related resources to support reconfigurations in the salesforce structure and activities (Hatami et al. Citation2016). As adaptive sales capability requires firms to reconfigure resources, processes, and activities, it tends to be resources and effort intensive in general, and in influencing technology-enabled sales capability in particular. Further, all resources and effort intensive strategies and activities need top management advocacy and support. Indeed, because many salesforce restructuring initiatives require reconfiguring the underlying technology resources used for sales purposes, greater top management technology advocacy can improve the likelihood of successfully implementing technology resource configuration (Speier and Venkatesh Citation2002). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H5c: Greater top management technology advocacy amplifies the positive relationship between adaptive sales capability and technology-enabled sales capability.

Moderating roles of technological and market turbulence

Consistent with the majority of research investigating the moderating role of turbulence in capabilities-based research, we examine the effect of environmental turbulence on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and technology-enables sales capability as well as between technology-enabled sales capability and performance outcomes (e.g., Coreynen et al. Citation2020; Vanpoucke, Vereecke, and Wetzels Citation2014; Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015). However, while some studies have investigated environmental turbulence as a single, aggregate construct (e.g., Auh and Menguc Citation2005), we follow prior scholars who investigate the moderating role of different types of turbulence separately (e.g., Hanvanich, Sivakumar, and Hult 2006; Kumar et al. Citation2011; Menguc and Auh Citation2006; Slater and Narver Citation1994; Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015). Specifically, because technological turbulence can influence how a firm structures its underlying technology resource-base, we contend that technological turbulence influences the relationship between dynamic capabilities and technology-enabled sales capability; whereas, because market turbulence can influence how the deployment of operational capabilities affects the achievement of business and financial objectives, we propose that market turbulence influences the relationship between technology-enabled sales capability and the two performance outcomes discussed above. In the following paragraphs, we provide a detailed rationale for the moderating role of each type of turbulence.

Technological turbulence

Possessing dynamic capabilities becomes more important for firms in more turbulent, vs. more stable, environments because a firm that lacks dynamic capabilities will struggle to align its operational capabilities with turbulent market conditions (Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015). The few studies that have investigated the moderating effect of technological turbulence on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and operational capabilities have found mixed results: some non-significant (e.g., Coreynen et al. Citation2020; Vanpoucke et al. Citation2014; Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015) and others positive (e.g., Carbonell and Rodriguez-Escudero Citation2014; Danneels and Sethi Citation2011). Such mixed findings prompted careful consideration regarding the role of technological turbulence in our model. Technological turbulence represents the degree and predictability of technological changes in an industry (Wilden and Gudergan Citation2015). When an industry experiences a higher degree of technological turbulence, dynamic capabilities become more important because firms are forced to alter and reconfigure their technology resource-base to keep up with the technological changes in the market (Teece Citation2007).

Accordingly, because technology-enabled sales capability encapsulates how firms leverage available technologies, when a firm experiences greater technological turbulence, technology sensing becomes more critical for being able to detect technological changes in the market. Indeed, firms that are more active at scanning for technology opportunities and threats will be better positioned to address higher levels of technological turbulence because “‘sensing’ requires learning about the environment and about new technological capabilities” (Teece Citation2007, 1339). Further, firms with higher technology sensing capability will be better positioned to take advantage of the additional technology-related opportunities that emerge under conditions of higher technological turbulence (Pavlou and El Sawy Citation2011). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H6a: Greater technological turbulence amplifies the positive relationship between technology sensing capability and technology-enabled sales capability.

In rapidly changing environments, vigilant market learning becomes more important for detecting, assessing, and acting on technological changes and understanding “how and when competitors, suppliers, and customers will respond” (Teece Citation2007, 1322). In fact, Hanvanich et al. (Citation2006) note that learning is critical for adapting to rapid technological changes. Furthermore, when an industry is experiencing rapid technological change, there are more opportunities from which a firm can learn and, in turn, improve existing organizational processes and routines (Pavlou and El Sawy Citation2011; Zollo and Winter Citation2002). Indeed, the literature suggests that learning is more critical for firms experiencing higher levels of technological turbulence (Zollo and Winter Citation2002). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H6b: Greater technological turbulence amplifies the positive relationship between vigilant learning capability and technology-enabled sales capability.

Additionally, rapid technological changes increase the importance of adaptive sales capability because such changes often require firms to adjust their sales structure and/or sales activities to accommodate new technologies. Indeed, several scholars have examined how significant technological changes have forced organizations to alter the way they conduct sales activities (e.g., Ahearne et al. Citation2008; Buehrer, Senecal, and Pullins 2005; Rapp et al. Citation2008; Singh et al. Citation2019). Further, because adaptive sales capability entails reconfiguration, greater technological turbulence is expected to enhance the value of adaptive sales capability (Teece et al. Citation1997). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H6c: Greater technological turbulence amplifies the positive relationship between adaptive sales capability and technology-enabled sales capability.

Market turbulence

Scholars investigate market turbulence to understand how a capability’s effectiveness is contingent on the degree and predictability of changes in customer demands and preferences in an industry (Jaworski and Kohli Citation1993; Tsai and Yang Citation2013). When market conditions are more volatile, firms are more likely to utilize newer technologies more often (Kim and Pae Citation2007). Thus, because technology-enabled sales capability entails leveraging technology to facilitate or reinforce activities in the sales process, firms that possess technology-enabled sales capability will be better positioned to use technology to understand and capitalize on changes in customers’ current and future needs, in turn, influencing firm performance outcomes.

Technology can be extremely important for uncovering key insights about customers (Day Citation2011), which can improve the firm’s ability to prospect potential customers and close sales (Jelinek et al. Citation2006; Zoltners, Sinha, and Lorimer Citation2020). Additionally, technology-related capabilities are more valuable when a firm is experiencing higher levels of market turbulence. Indeed, Wang et al. (Citation2015) note that “market turbulence is often driven by intense competition and unpredictable timing of technological advances… making technology-related capabilities more desirable, and forcing companies to invest more in technological competencies in order to keep up with the competition” Thus, in the context of high market turbulence, by drawing more effectiveness and efficiency from technology resources, the sales function can accrue competitive advantages. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H7a: Greater market turbulence amplifies the positive relationship between technology-enabled sales capability and a firm’s financial performance

Further, technology-enabled sales capability becomes critical for account management capability when there is market turbulence because firms extensively rely on technology for acquiring new customers and for developing and maintaining customer relationships (Becker, Greve, and Albers Citation2009; Rodriguez, Peterson, and Krishnan Citation2012). Additionally, technology, when used to provide on-the-job sales training (e.g., Lassk et al. Citation2012), can be used to help a firm be more customer-oriented and improve a firm’s salesmanship skills (Román, Ruiz, and Luis Munuera Citation2002) especially when firms are in an industry experiencing higher market turbulence. Thus, technology-enabled sales capability is more critical for customer relationship performance when firms are experiencing higher levels of market turbulence. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H7b: Greater market turbulence amplifies the positive relationship between technology-enabled sales capability and a firm’s customer relationship performance.

Method

Sample and data collection

Using the services of Centiment, a marketing research company, data were collected through an online survey of business-to-business sales managers employed in organizations across different industries in the United States. This population was deemed appropriate for this study since sales managers are (1) at the forefront of navigating shifts in sales force tasks, personnel, structure, and notably, technology brought about by the exogenous shock of the COVID-19 pandemic (Hartmann and Lussier Citation2020), (2) actively involved in implementing and fostering adoption of technology within the sales function (Alavi and Habel Citation2021; Schillewaert et al. Citation2005), and (3) sufficiently aware of organizational capabilities, sales capabilities, and relative performance outcomes (Alavi and Habel Citation2021; Schillewaert et al. Citation2005; Siahtiri et al. Citation2014). Respondents were screened for their knowledge regarding their firms’ investments in sales force technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic and only those respondents who reported high levels of knowledge were qualified to complete the survey. A follow-up question regarding technological investments in specific sales processes and routines (e.g., hardware and software for customer relationship management, communication and interactions, productivity, research and analytics, monitoring and tracking, etc.) was also employed for additional validation. In addition to the screening questions, attention and speeding checks were incorporated in the survey to preserve response quality. To maintain objectivity (Babin, Griffin, and Hair Citation2016), the research company removed respondents who failed these checks before delivering the dataset to the researchers. Overall, 224 qualified respondents completed the survey. About sixty (forty) percent of the respondents were male (female) and the average age was reported as approximately 47 years.

Measures

All constructs in the proposed framework were measured at the organizational level using multi-item, seven-point scales. As for the three dynamic organizational capabilities, technology sensing capability was measured using a scale from Srinivasan et al. (Citation2002), vigilant market learning capability was measured using a scale developed by Guo et al. (Citation2018), and adaptive sales capability was measured using a scale from Spiro and Weitz (Citation1990) that was modified to broaden the scope beyond sales behaviors and capture an organization’s ability to alter its sales activities, sales strategies, and sales force structure in accordance with market changes. The key operational sales capability, technology-enabled sales capability was measured by adapting scales on sales capabilities (e.g., Krush et al. Citation2013; Siahtiri et al. Citation2014) to capture the extent to which emergent technology was leveraged or deployed to enrich sales processes and activities. Consistent with our definition, a pool of items was identified to capture an organization’s ability to embed technology within the sales function’s activities and processes. These items were then evaluated by four marketing academicians who were not associated with the study to determine face validity and adequacy. Subsequently, the items were shared with four sales executives and based on their feedback, were subjected to additional minor refinements. Through these steps, a final set of parsimonious and representative items was generated. Notably, whereas existing measures of firm-level sales capabilities (e.g., Krush et al. Citation2013; Siahtiri et al. Citation2014) examine aspects of organizational knowledge, skills, and resources to engage in selling activities, in general, the current scale merges technology with sales capabilities and assesses the extent to which firms deploy, leverage, exploit, and integrate technology to assist the activities of the sales function.

As for the two performance outcomes, financial performance was measured by borrowing items from Menguc and Auh (Citation2006) and Morgan, Vorhies, and Mason (Citation2009), while relational performance was measured using a scale from Rapp et al. (Citation2010). Finally, as for the moderating variables, top management technology advocacy was measured using a scale developed by Srinivasan et al. (Citation2002), while technological turbulence and market turbulence were assessed using scales reported by Wilden and Gudergan (Citation2015). Scales for all constructs were anchored with 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 7 = “Strongly Agree,” except financial performance and relational performance which had 1 = “Much Worse Than Competitors” and 7 = “Much Better Than Competitors” as anchors.

Preliminary analysis

Data analysis was conducted using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS 3.0. PLS-SEM is regarded as a suitable analytical procedure for testing complex theoretical frameworks from a prediction perspective (Hair et al. Citation2019) and has been utilized in several recent sales studies published in leading marketing and business journals (e.g., (Badrinarayanan, Gupta, and Chaker Citation2021; Bolander et al. Citation2015; Dugan et al. Citation2019). Following recommended guidelines, we adopted a two-step analytical procedure in which we evaluated the measurement model, before analyzing the structural model and testing hypotheses (Hair et al. Citation2019).

Accordingly, in the first step, the following procedures were undertaken to evaluate the adequacy and psychometric properties of all latent constructs. First, we examined individual item loadings to assess item reliability. Outer loadings of all items, except one item each for technology sensing capability and technological turbulence, exceeded the recommended cutoff of .708 [range .73 to .90] (Hair et al. Citation2019), thus offering evidence that respective constructs explain more than 50% of an indicator’s variance. The two items with low loadings were dropped from further analysis after determining that eliminating them did not diminish their respective construct’s content validity. Second, we examined construct reliability values to assess internal consistency reliability. Cronbach’s alphas [range .70 to .88], composite reliabilities [range .82 to .92], and ρA [range .71 to .89] fall within acceptable thresholds (Hair et al. Citation2019), offering sufficient support for internal consistency reliability of all latent constructs included in the study. Third, we evaluated the average variance extracted (AVE) values to assess convergent validity of construct measures. The AVE values exceeded the recommended threshold of .50 [range .60 to .78], thus indicating that each construct converges to explain more than 50% of variance of its items (Hair et al. Citation2019). Fourth, we examined differences between AVE values and shared variances as well as the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations to evaluate discriminant validity. As the square root of the AVE for each construct was greater than that construct’s shared correlations with other constructs (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981) and as the HTMT ratio of average correlations of indicators across constructs [range .39 to .89] was below the recommended cutoff of 0.90 (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2015), it was concluded that each construct is empirically distinct from other constructs in the model (Hair et al. Citation2019). Finally, we checked for multicollinearity by examining the variance inflation factor (VIF) scores. As all VIF scores were well below 5 [range 1.42 to 2.52], it was concluded that multicollinearity was not a problem. All items, loadings, Cronbach’s alphas, composite reliabilities, and ρA are provided in . Construct properties such as means, standard deviations, inter-construct correlations, and AVEs are provided in . The matrix of HTMT values is provided in .

Table 2. Construct properties.

Table 3. Correlations, means, standard deviations, and AVEs.

Table 4. Matrix of Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios of correlations.

Given that data were collected from a single source, we undertook several steps to control for and evaluate common method variance, which “occurs when responses systematically vary because of the use of a common scaling approach on measures derived from a single data source” (Fuller et al. Citation2016, 3192). While designing the survey, we implemented procedural precautions to avoid or counterbalance the effects of common method variance, such as reviewing questions to fix ambiguous wording, presenting questions for independent and dependent variables in different sections, promising anonymity to respondents and stating upfront that there are no right or wrong answers for survey questions, and employing different scale anchors to measure latent constructs (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). Next, we employed Harman’s one-factor test, and the factor solution revealed that no single factor accounts for a majority of the variance explained in the measurement items (Podsakoff and Organ Citation1986). Finally, the marker variable approach (Lindell and Whitney Citation2001; Podsakoff et al. Citation2003) was applied and no notable differences were observed in either the predictive relevance of endogenous constructs or the statistical significance of theorized paths when comparing path models with and without the addition of an unrelated marker variable, attitude toward the color blue (Simmering et al. Citation2015). These precautions and tests, in addition to the study’s utilization of reliable and valid measures (Fuller et al. Citation2016), offer confidence that common method variance is not a threat to the relationships in the proposed model.

Hypotheses tests

As the measurement model assessment yielded satisfactory results, we proceeded to test the proposed hypotheses using 5000 bootstrapping sample runs to evaluate statistical significance. Overall, the results from the structural model analysis provide support for all of the five hypothesized direct effects (see ). Technology sensing capability (β = .48; p < .001), vigilant market learning capability (β = .20; p < .05), and adaptive sales capability (β = .15; p < .05) were found to be positively related to technology-enabled sales capability, thus supporting H1, H2, and H3, respectively. Further, technology-enabled sales capability was positively related to both financial performance (β = .49; p < .001), and relationship performance (β = .48; p < .001), thus supporting H4(a) and H4(b), respectively.

Subsequently, we evaluated the moderating effects of top management technology advocacy and technological turbulence as specified in the theoretical framework. For this purpose, we employed the two-stage calculation approach, where the latent variable scores of the latent predictors and latent moderator variables are computed in the first stage and used to calculate the product indicator for the interaction term that is added in the second stage of analysis. Top management technology advocacy was found to positively moderate the effects of vigilant market learning capability (β = .08; p < .05) and adaptive sales capability (β = .08; p < .05)—but not the effect of technology sensing capability—on technology-enabled sales capability. Thus, whereas H5(a) was not supported, both H5(b) and H5(c) were supported. Next, technological was found to positively moderate the effects of technology sensing capability (β = .09; p < .05) and vigilant learning capability (β = .11; p < .05)—but not the effect of adaptive sales capability—on technology-enabled sales capability. Thus, while H6(a) and H6(b) were supported, H6(c) was not. Finally, market turbulence was found to positively moderate the effects of technology-enabled sales capability on relational performance (β = .14; p < .10) but not financial performance, thus offering support for H7(b) and not H7(a). The results from hypotheses tests are presented in . Although not hypothesized, we evaluated whether technology-enabled sales capability mediates the effects of the three dynamic organizational capabilities on the two performance outcomes. In addition to the significant paths from the three dynamic organizational capabilities to technology-enabled sales capability as well as from technology-enabled sales capability to the two performance outcomes, the direct effects from the three dynamic organizational capabilities to the two performance outcomes were also significant, thus indicating the presence of complementary (partial) mediation effects. Specifically, technology-sensing capability, vigilant learning capability, and adaptive sales capability were positively related to financial performance (β’s = .23, .10, and .07, respectively; p < .05) and relationship performance (β’s = .22, .09, and .07, respectively; p < .05). Finally, we investigated whether relationship performance was related to financial performance. As demonstrated in previous research (e.g., Rapp et al. Citation2010), we also found a significant positive relationship between these variables (β = .55; p < .05).

Table 5. Results from hypotheses tests.

Next, we evaluated the explanatory power, predictive relevance, and robustness of the proposed model. To ascertain the explanatory power of the model, R2 (the coefficient of determination) and Q2 (the blindfolding-based cross-validated redundancy measure) values were examined for key endogenous variables. The R2 and Q2 values, respectively, for technology-enabled sales capability performance (52.8%, p < .001; .39), financial performance (23.9%, p < .001; .18) and relational performance (22.7%, p < .001; .16), suggest that the model has adequate predictive relevance (Hair et al. Citation2019). To estimate the model’s out-of-sample predictive power, PLSpredict was used to execute k-fold cross-validation with 10 subgroups. None of the indicators of both endogenous latent variables, financial performance and relational performance, demonstrate higher root mean squared error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE) in the PLS-SEM analysis when compared to the naïve benchmark linear regression model (LM), thus indicating that the proposed model has high predictive power (Hair et al. Citation2019). In the following section, we discuss the results and highlight theoretical and managerial implications based on our findings.

Discussion

As organizations are emerging from the disruptions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is becoming evident that their approach toward the sales function has transformed permanently, specifically with regard to how they are leveraging technological resources to enhance sales operations (Bages-Amat et al. Citation2020). Sales researchers have begun to investigate this phenomenon by exploring issues such as how to transform the sales function through digitization (Guenzi and Habel Citation2020), how sales managers can unlearn outdated practices and embrace technology infusion (Mattila et al. Citation2021), and how salespeople can be motivated to use emergent technologies (Mullins and Agnihotri Citation2022). The current study complements this evolving body of knowledge by adopting a novel theoretical perspective that integrates knowledge on dynamic capabilities and sales capabilities to conceptualize technology-enabled sales capability, a firm-level capability that relates to how the embeddedness of technological resources enhances operational capabilities of the sales function.

In our empirical analysis, we test a holistic framework of technology-enabled sales capability that captures how dynamic capabilities (i.e., technology-sensing capability, vigilant learning capability, and adaptive sales capability) influence performance outcomes (i.e., financial performance and relational performance) through operational sales capabilities (i.e., technology-enabled sales capability) contingent on certain organizational (i.e., top management technology advocacy) and environmental factors (i.e., technology turbulence and market turbulence). Below, we outline our theoretical and managerial contributions.

Theoretical contributions

First, our study contributes to literature on technology and the sales function, which has hitherto been heavily skewed toward research on the salesperson-level of analysis, by drawing attention to firm-level capabilities that enable firms to better manage technological resources pertaining to the sales function. Although prior researchers have alluded to the role of firm-level dynamic capabilities in engendering functional unit-level operational capabilities (Day 2012), analogous to research on capabilities of the marketing function (Vorhies and Morgan Citation2005), very little research exists on how organizational capabilities exert antecedent effects on capabilities of the sales function. Thus, our study extends the literature on firm-level dynamic capabilities and sales capabilities by demonstrating the relevance of specific dynamic capabilities that enable organizations to sense and respond to environmental changes and contribute toward enhancing capabilities of the sales function. Although prior researchers have examined technology-sensing capability, vigilant learning capability, and adaptive sales capability in different contexts—to our knowledge—no prior study has examined their influence on operational capabilities of the sales function. Thus, the current study adds to extant research on sales-related capabilities (e.g., Krush et al. Citation2013; Siahtiri et al. Citation2014) by identifying relevant firm-level dynamic capabilities that facilitate operational capabilities at the sales function level.

Second, we contribute to the sales literature by drawing attention to a newly conceptualized construct—technology-enabled sales capability. While prior researchers have expounded on how firms can deploy their sales capability (e.g., (Krush et al. Citation2013; Siahtiri et al. Citation2014), attention has not been afforded to how firms can leverage technology to enhance their sales operations. At the intersection of sales and technology, technology-enabled sales capability is distinct from context-deficient “technology capability” or technology-deficient “sales capability” and, as such, can be an important construct to complement emerging research on digital transformation in sales, digitization and digital selling, and artificial intelligence in sales. Importantly, we demonstrate that technology-enabled sales capability is positively related to financial performance and customer relationship performance, which adds to the limited research on the consequences of firm-level capabilities pertaining to the sales function (Guenzi et al. Citation2016).

Third, by examining top management technology advocacy and environmental turbulence, we contribute to research on how internal and external environment factors affect firms’ abilities to develop and deploy operational capabilities. By evaluating the effects of distinct facets of environmental turbulence, which yield mixed results, we provide preliminary evidence that investigating environmental turbulence as an aggregate construct may result in loss of meaning. The results illustrate that the impact of dynamic capabilities on technology-enabled sales capability is bolstered by top management technology advocacy and technological turbulence, thus highlighting how dynamic capabilities can be fully leveraged to enhance functional capabilities with adequate top management support for technology and in times of rapid technological advancements. Further, the results also support that the impact of technology-enabled sales capability on relationship performance is strengthened by market turbulence, thus demonstrating business value of leveraging technology-enabled sales capability especially during periods of rapidly shifting market conditions. Contrary to our expectations, the proposed moderating effect of top management technology advocacy on the relationship between technology sensing and technology-enabled sales capability was not supported. This could be attributed to the fact that technology sensing capability is already driving organizations to detect and respond to changes in the technological environment and, thus, top management advocacy of technology is not necessarily a catalyst for augmenting its impact on technology-enabled sales capability. Similarly, the proposed moderating effect of technological turbulence on the relationship between adaptive sales capability and technology-enabled sales capability was not supported, suggesting that the posited direct relationship does not fluctuate with technological disruptions. Finally, the proposed moderating effect of market turbulence on the relationship between technology-enabled sales capability and financial performance was also not supported, perhaps indicating that the direct relationship remains relevant irrespective of whether market characteristics are stable or shifting. By unearthing the varying effects of different types of turbulence on the effects of dynamic and functional capabilities, this study extends current knowledge by demonstrating the added value in disentangling such environmental variables.

Managerial contributions

For managers, we offer several actionable directions. For firms emerging from the grips of the COVID-19 pandemic, we demonstrate the importance of developing robust dynamic and operational capabilities. As these capabilities are critical for sensing and responding to changes in the business landscape, firms must invest in developing a portfolio of capabilities that enable them to cope with environmental shifts. Without question, the COVID-19 pandemic created unexpected and unprecedented disruptions for organization and the sales function. Yet, a valuable lesson from this pandemic is to future-proof organizations by identifying capabilities that help with continuously combining and reconfiguring resources such that firms are better able to handle emergent exogenous shocks.

First, we suggest that the value of technology is contingent upon the extent to which organizations are able to integrate technological resources with function-specific resources to create technology-enabled capabilities. That is, organizations must carefully consider the complementary value of technological resources as well as their ability to seamlessly integrate it within business functions to realize operational benefits. Indeed, our results show that when organizations integrate technological resources with activities and processes of the sales function, the resultant technology-enabled sales capability leads to superior financial and relationship performance. Second, it is apparent that organizations that utilize dynamic capabilities will be better positioned to reconfigure resources and enhance operational capabilities that are critical for capturing marketplace advantages. In line with this reasoning, we identify specific firm-level dynamic capabilities that could be utilized by organizations to influence technology-enabled sales capability, which we show as important for financial and relational performance. Specifically, when organizations are dynamically scanning the environment for new technological advances (i.e., technology sensing), adopting an agile and customer-oriented approach toward trends in market (i.e., vigilant market learning), and adapting their sales approaches to suit the characteristics of key customers (i.e., adaptive selling), they are more likely to integrate technological resources with sales capabilities. Thus, the leveraging of these dynamic capabilities is a theoretically grounded explanation as to why some firms are better than others in harnessing technological resources for sustaining sales operations. To function effectively in the post-pandemic “new normal,” organizations must develop and deploy an array of dynamic capabilities for continuously making sense of the environment and orchestrating resources for the cultivation of operational capabilities. Toward this end, organizations must assess and diagnose gaps in their capabilities dashboard, acquire and strengthen vital capabilities, monitor implementation of these capabilities, and constantly recalibrate capabilities based on organizational learning (Day Citation1994).

Third, an additional actionable implication is that top management needs to emphasize the importance of technology and champion the integration of technology to reconfigure existing resources. The influence of dynamic capabilities, notably vigilant market learning and adaptive sales capabilities, on technology-enabled sales capability is strengthened when top management strongly advocates the importance of technology. Fourth, managers should also note that the effects of dynamic capabilities on technology-enabled sales capability are amplified during periods of technological turbulence. Thus, when rampant shifts are occurring in the technological environment, dynamic capabilities should be vital for identifying and deploying appropriate technological resources for enhancing sales operations. Similarly, when there are high levels of market turbulence, our results indicate that technology-enabled sales capability will hold organizations in good stead with respect to managing relational performance. For organizations investing in digital transformation and sales enablement, periodic assessment of their technology-enabled sales capability could provide timely feedback on whether their investments are yielding targeted improvements in the sales function, sales force, and sales activities.

Limitations and future research directions

First, we acknowledge that the current conceptualization of the focal construct, technology-enabled sales capability, focuses broadly on how technology can be leveraged to enhance sales operations. However, this perspective does not encompass aspects of sales management such as hiring, training, onboarding, and evaluation of sales talent—areas which are witnessing rapid integration of technology (Wiseman et al. Citation2022). Future research can expand on our current conceptualization and evaluate the feasibility of additional dimensions of technology-enabled sales capability. Second, we acknowledge that our exploration offers insight into development and deployment of firm capabilities solely from the sales manager perspective. Although prior studies have adopted this approach (e.g., Schillewaert et al. Citation2005) given that sales managers are well informed about organizational capabilities, integration of technology in the sales function, operational sales capabilities, and performance outcomes (Alavi and Habel Citation2021; Badrinarayanan et al. Citation2019), the perspectives of senior sales executives, managers in other functional units, frontline salespeople, and customers are not included in our framework. Therefore, future studies can further enrich our understanding of the role of technology-enabled sales capability by investigating factors such as resource constraints, rigidities, and orchestration (Badrinarayanan et al. Citation2019), marketing-sales interface characteristics (Mullins and Agnihotri Citation2022), salespeople’s utilization of and satisfaction with sales technologies (Habel, Alavi, and Linsenmayer Citation2021), and customer preferences and responses (Ahearne et al. Citation2022) by collecting data from different sets of respondents. Third, while we limited our attention to examining the moderating effect of one internal environment factor, namely, top management advocacy for technology, we acknowledge the scope for future research to consider additional organizational capabilities, orientations, and affinity for technology (Fleming and Artis Citation2010). Fourth, since our analysis relied on data from a cross-sectional, single-source survey, we acknowledge inherent limitations on assessing causality and generalizability. To overcome this, future studies can undertake longitudinal explorations and field experiments with data from multiple sources, including objective performance measures, and provide a more nuanced understanding of the antecedents and consequences of technology-enabled sales capability. On a related note, given that the scales for the dynamic capabilities and technology-enabled sales capability are newly adapted to the sales literature, future studies can further validate these scales in their explorations. Furthermore, given that the proposed framework included conceptually similar variables that were all measured at the firm-level, three HTMT values were between the conservative and liberal thresholds of .85 and .90, respectively (Hair et al. Citation2019). Future researchers need to pay attention to the discriminant validity of these constructs, potentially by drawing data from different populations and through statistical tests. Fifth, we acknowledge that the proposed model could be strengthened by the inclusion of additional antecedents (e.g., strategic orientation, dynamic managerial capabilities, etc.), mediating variables (e.g., other operational capabilities and process variables), and control variables (e.g., industry type, multinational vs. national operations, and firm characteristics). Given that continuous technology integration within the sales function will be an ongoing trend in the foreseeable future, we conclude with a call for more systematic research on how organizations can enhance their capabilities to sense and respond to emergent technological developments that benefit their sales operations and overall performance.

Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ahearne, Michael, Yashar Atefi, Son K. Lam, and Mohsen Pourmasoudi. 2022. “The Future of Buyer–Seller Interactions: A Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 50 (1):22–45. doi: 10.1007/s11747-021-00803-0.

- Ahearne, Michael, Douglas E. Hughes, and Niels Schillewaert. 2007. “Why Sales Reps Should Welcome Information Technology: Measuring the Impact of CRM-Based IT on Sales Effectiveness.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 24 (4):336–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2007.09.003.

- Ahearne, Michael, Eli Jones, Adam Rapp, and John Mathieu. 2008. “High Touch through High Tech: The Impact of Salesperson Technology Usage on Sales Performance via Mediating Mechanisms.” Management Science 54 (4):671–85. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1070.0783.

- Ahearne, Michael, and Adam Rapp. 2010. “The Role of Technology at the Interface between Salespeople and Consumers.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 30 (2):111–20. doi: 10.2753/PSS0885-3134300202.

- Alavi, Sascha, and Johannes Habel. 2021. “The Human Side of Digital Transformation in Sales: Review & Future Paths.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 41 (2):83–6. doi: 10.1080/08853134.2021.1920969.

- Auh, Seigyoung, and Bulent Menguc. 2005. “The Influence of Top Management Team Functional Diversity on Strategic Orientations: The Moderating Role of Environmental Turbulence and Inter-Functional Coordination.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 22 (3):333–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2004.12.003.

- Ayabakan, Sezgin, Indranil R. Bardhan, and Zhiqiang Zheng. 2017. “A Data Envelopment Analysis Approach to Estimate IT-Enabled Production Capability.” MIS Quarterly 41 (1):189–205. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.1.09.

- Babin, Barry J., Mitch Griffin, and Joseph F. Hair. 2016. “Heresies and Sacred Cows in Scholarly Marketing Publications.” Journal of Business Research 69 (8):3133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.12.001.

- Badrinarayanan, Vishag, Aditya Gupta, and Nawar N. Chaker. 2021. “The Pull-to-Stay Effect: Influence of Sales Managers’ Leadership Worthiness on Salesperson Turnover Intentions.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 41 (1):39–55. doi: 10.1080/08853134.2020.1820347.

- Badrinarayanan, Vishag, Sreedhar Madhavaram, and Elad Granot. 2011. “Global Virtual Sales Teams (GVSTs): A Conceptual Framework of the Influence of Intellectual and Social Capital on Effectiveness.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 31 (3):311–24. doi: 10.2753/PSS0885-3134310308.

- Badrinarayanan, Vishag, Indu Ramachandran, and Sreedhar Madhavaram. 2019. “Resource Orchestration and Dynamic Managerial Capabilities: Focusing on Sales Managers as Effective Resource Orchestrators.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 39 (1):23–41. doi: 10.1080/08853134.2018.1466308.

- Bages-Amat, Arnau, Liz Harrison, Dennis Spillecke, and Jennifer Stanley. 2020. “These Eight Charts Show How COVID-19 Has Changed B2B Sales Forever.” McKinsey & Company (October):1–11.

- Barney, Jay B. 1991. “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage.” Journal of Management 17 (1):99–120. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700108.

- Becker, Jan U., Goetz Greve, and Sönke Albers. 2009. “The Impact of Technological and Organizational Implementation of CRM on Customer Acquisition, Maintenance, and Retention.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 26 (3):207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2009.03.006.

- Benitez, Jose, Gautam Ray, and Jörg Henseler. 2018. “Impact of Information Technology Infrastructure Flexibility on Mergers and Acquisitions.” MIS Quarterly 42 (1):25–43. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2018/13245.

- Bhatt, Ganesh D., and Varun Grover. 2005. “Types of Information Technology Capabilities and Their Role in Competitive Advantage: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Management Information Systems 22 (2):253–77. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2005.11045844.

- Bolander, Willy, Cinthia B. Satornino, Douglas E. Hughes, and Gerald R. Ferris. 2015. “Social Networks within Sales Organizations: Their Development and Importance for Salesperson Performance.” Journal of Marketing 79 (6):1–16. doi: 10.1509/jm.14.0444.

- Buehrer, Richard E., Sylvain Senecal, and Ellen Bolman Pullins. 2005. “Sales Force Technology Usage - Reasons, Barriers, and Support: An Exploratory Investigation.” Industrial Marketing Management 34 (4):389–98. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.09.017.

- Carbonell, Pilar, and Ana Isabel Rodriguez-Escudero. 2014. “Antecedents and Consequences of Using Information from Customers Involved in New Service Development.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 29 (2):112–22. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-04-2012-0071.

- Carpenter, Mason A., Marta A. Geletkanycz, and Wm Gerard Sanders. 2004. “Upper Echelons Research Revisited: Antecedents, Elements, and Consequences of Top Management Team Composition.” Journal of Management 30 (6):749–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.001.

- Chatterjee, Sheshadri, Ranjan Chaudhuri, and Demetris Vrontis. 2022. “Does Remote Work Flexibility Enhance Organization Performance? Moderating Role of Organization Policy and Top Management Support.” Journal of Business Research 139 (November 2021):1501–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.069.

- Clemons, Eric K., and Michael C. Row. 1991. “Sustaining IT Advantage: The Role of Structural Differences.” MIS Quarterly 15 (3):275–92. doi: 10.2307/249639.

- Coreynen, Wim, Paul Matthyssens, Johanna Vanderstraeten, and Arjen van Witteloostuijn. 2020. “Unravelling the Internal and External Drivers of Digital Servitization: A Dynamic Capabilities and Contingency Perspective on Firm Strategy.” Industrial Marketing Management 89:265–77. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.014.

- Cron, William L., Artur Baldauf, Thomas W. Leigh, and Samuel Grossenbacher. 2014. “The Strategic Role of the Sales Force: Perceptions of Senior Sales Executives.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 42 (5):471–89. doi: 10.1007/s11747-014-0377-6.