Abstract

Retaining talented salespeople is crucial for a company’s survival. One effective strategy for retaining employees is to actively involve them in significant business decisions. Salespeople, however, differ significantly from their colleagues, for example, they are typically highly customer-oriented. Therefore, integrating them into new product development (NPD) may be a potentially valuable approach for firms to retain them. Nonetheless, salesforce integration (SI) into NPD is more intricate than initially thought. It may involve both psychological SI benefits (such as feeling valued or competent) and costs (including potential conflicts with NPD team members or role conflicts), thus differently affecting a salesperson’s willingness to stay with the firm. To learn more about the intriguing link between SI into NPD and salesperson retention, we conducted a qualitative study and applied grounded theory to conceptualize this relationship. We identify key mediators (psychological SI benefits and costs) and moderators (such as company, NPD team, salesperson, procedural, relationship, or product characteristics) that can influence the SI-into-NPD-salesperson-retention connection and develop related, relevant propositions. All of these insights are integrated into a cohesive framework and we present a research agenda to guide future exploration of this critical subject. Furthermore, we derive and discuss implications for both academics and practitioners.

Introduction

Retaining talented salespeople within a company stands as one of the "most enduring and perplexing problems managers face" (Boles et al. Citation2012, 138) and is critical for the long-term viability of firms (Vomberg, Homburg, and Bornemann Citation2015). Research demonstrates that, beyond "hygiene factors" like satisfactory compensation or time off, salespeople are particularly inclined to remain with their firm when they exhibit commitment to it, feeling that they are genuinely integrated into the organization (Boles et al. Citation2012; Futrell and Parasuraman Citation1984; Rosenberg et al. Citation1981).

Yet, although prior studies show that engaging employees in important business decisions may enhance their organizational commitment (Han, Chiang, and Chang Citation2010; Ohana, Meyer, and Swaton Citation2013) and thus help organizations to retain their employees to the firm (Cole and Bruch Citation2006; DeConinck Citation2011a), triggering this commitment in salespeople is particularly challenging. This is especially the case as they differ substantially from other employees within the firm. They are not only typically geographically distant from headquarters, either due to extensive travel or working in remote branches (Chernetsky, Hughes, and Schrock Citation2022; Rouziès et al. Citation2005). They also exhibit specific mindsets, characterized by a high degree of goal orientation (Challagalla and Shervani Citation1996; MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Paine Citation1999) and a strong emphasis on satisfying customer needs (Habel et al. Citation2020; Pass, Evans, and Schlacter Citation2004). Hence, it is essential for firms to find new and innovative ways, especially for retaining salespeople, in order to successfully continue selling their products.

Considering salespeople’s exceptional customer orientation, enabling them to participate in decisions that help better serve customer needs can significantly boost their job satisfaction and their identification with the company (Gammoh, Mallin, and Pullins Citation2014). Integrating salespeople into new product development may serve as a catalyst for that. Consequently, the integration of salespeople (SI) into new product development (NPD) has been a subject of debate from various perspectives (Annunen et al. Citation2021; Kuester, Homburg, and Hildesheim Citation2017). Having the closest contact to the customer, salespeople possess more tacit market knowledge than any other function, such as R&D, operations, or marketing (Ahearne et al. Citation2013; Homburg and Jensen Citation2007), thus helping discover customer needs and latent business opportunities (Liu and Comer Citation2007; Thietart and Vivas Citation1981). Moreover, their direct customer contact allows them to collect customer information particularly quickly and efficiently (Pass, Evans, and Schlacter Citation2004). Hence, scholars and practitioners unequivocally agree that including the salespeople into new product development (NPD) can substantially help enhance NPD performance (Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen Citation2010; Joshi Citation2010; Kuester, Homburg, and Hildesheim Citation2017).

However, not just "hard" outcomes in terms of economic SI outcomes (such as the product’s performance in the market) can result from SI into NPD. Particularly concerning "soft" or social outcomes (in terms of retaining salespeople in the firm), SI into NPD may be a compelling catalyst, yet also a double-edged sword. On one hand, it may entail significant psychological SI costs for an individual salesperson, such as new and additional tasks, increased workloads, or potential conflicts with existing responsibilities, all of which essentially represent adverse outcomes. On the other hand, SI into NPD may offer psychological SI benefits, yielding positive results like improved networks within the firm and an opportunity to fulfill a salesperson’s inherent desire to serve her/his customers effectively.

However, the soft SI outcomes of SI into NPD have not been adequately considered or conceptualized. Thus, it is challenging to form a comprehensive understanding of the impact of SI into NPD on salesperson retention, along with the potential underlying psychological SI benefits and costs. This also renders the role of SI into NPD on salesperson retention uncertain across different contexts, including variations in product or customer importance, NPD teams, or a firm’s internal structures.

Hence, our study unravels the "black box" of SI into NPD's role in retaining salespeople within the firm and organizes it into a structured framework. Given the surprising dearth of literature on the softer outcomes of SI into NPD, our research is grounded in a qualitative study employing a grounded theory approach, and it contributes to the discipline in the following three ways:

First, drawing from our qualitative study and grounded theory approach, we conceptualize the specific potential of SI into NPD for retaining salespeople within the organization. This involves the identification of key mechanisms, encompassing both positive mechanisms related to SI into NPD's impact on salesperson retention (in terms of psychological SI benefits) and negative mechanisms (in terms of psychological SI costs), for which we derive respective propositions. Second, building on our grounded theory approach, we develop propositions regarding how the relationship between SI into NPD and salesperson retention, as well as the underlying mechanisms, may vary based on different situational characteristics. These characteristics may include company, NPD team, salesperson, procedural, relationship, or product characteristics. This theoretical framework can assist academics and practitioners in navigating the fine line and understanding the double-edged nature of SI into NPD, considering both its benefits and costs. Third, we systematically organize all the constructs and propositions within a coherent framework. Based on these findings, we outline a research agenda for future exploration, where our framework can serve as a foundational model for developing innovative concepts and advancing the study of this intriguing yet under-researched field.

Literature review

Multiple literature fields can help explore the role of SI into NPD for salesperson retention. They include not only functional-spanning studies on cross-functional integration in NPD and employee retention but also sales-specific work, such as on SI into NPD and salesperson retention. We will focus on the latter two fields but occasionally also draw on insights from the other two more general literature streams.

Literature on SI into NPD

Research repeatedly recognized the positive outcomes of integrating various functions into NPD (e.g. Griffin and Hauser Citation1996), resulting in a large field of research on cross-functional integration (e.g. Brockman et al. Citation2010; De Luca and Atuahene-Gima Citation2007; Moenaert and Souder Citation1990; Sethi Citation2000). Yet, the sales department as one of the integrated functions has long been ignored, but eventually resulted in a solid body of literature (e.g. Chernetsky, Hughes, and Schrock Citation2022; Dewsnap and Jobber Citation2000, Hughes, Le Bon, and Malshe Citation2012, Rouziès et al. Citation2005). A key part of the studies in this research field is that they clearly recognize the importance of salespeople as a valuable information supplier for NPD (e.g. Gordon et al. Citation1997; Judson et al. Citation2006; Rochford and Wotruba Citation1993). In this context, salespeople have proven to be highly relevant for exchanging so-called tacit knowledge, which is not readily available through classic market research, such as regular customer surveys or marketing analyses (Arnett, Wittmann, and Hansen Citation2021; Arnett and Wittmann Citation2014; Le Bon and Merunka Citation2006).

Unsurprisingly, a large part of research on SI into NPD explicitly explores the performance outcomes of SI into NPD, especially with regard to organizational outcomes, such as product quality or market performance of new products (e.g. Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen Citation2010; Kuester, Homburg, and Hildesheim Citation2017; Li and Calantone Citation1998; Panagopoulos, Rapp, and Ogilvie Citation2017). For example, Joshi (Citation2010) reveals how salespeople succeed at integrating their desired product ideas into NPD and shows that relatedly achieved product modifications can substantially increase products’ market performance. In this context, the work by Kuester, Homburg, and Hildesheim (Citation2017) has shown that to improve product’s market performance, two important mediators play a crucial role, namely sales force adoption and new product advantages whereas Panagopoulos, Rapp, and Ogilvie (Citation2017) highlight the importance of relationship characteristics. However, integrating salespeople for enhancing new products may be differently effective across different stages of the NPD process and cooperation formats. For example, Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen (Citation2010) show that cooperation of salespeople with R&D in the concept and product development stages is crucial for increasing the market share and the financial performance of the new product and that cooperation with marketing is especially relevant in the concept development and implementation phase of NPD.

Newer work on SI into NPD points to the role of fostering proper NPD implementation processes for the sales force, so that they can effectively sell the new products in the market (e.g. Kuester and Rauch Citation2016; Le Bon and Merunka Citation2006). As such, providing salespeople with adequate information on the new product can substantially alter their cost perception on selling a new product, thus affecting their efforts to sell the new product (Van der Borgh and Schepers Citation2018). Specifically, the importance of sales-related planning may vary within the NPD process so that firms need to systematically manage respective NPD sales activities across different phases (Annunen et al. Citation2021; Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen Citation2010) or together with different functions (Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen Citation2010; Homburg et al. Citation2017).

Overall, the literature on SI into NPD provides solid information on organizational outcomes, especially those targeted to the market and thus externally relevant outcomes, such as new product improvements or performance. However, it misses to explore internally relevant outcomes, such as the impact on the involved sales personnel, especially in terms of salesperson retention. In addition, we note that research so far has not investigated either determinants driving SI into NPD.

Literature on salesperson retention

Research on employee retention, or conversely, employee turnover, boasts a long-standing tradition spanning over half a century (e.g. Brown and Peterson Citation1993; Futrell and Parasuraman 1984; Porter and Steers Citation1973), in which researchers have pinpointed a diverse range of factors influencing employee retention or turnover (Allen, Bryant, and Vardaman Citation2010; Hom et al. Citation2017). This vast body of literature has been extensively reviewed in multiple studies (e.g. Boles et al. Citation2012; Brown and Peterson Citation1993; Holtom et al. Citation2008) and meta-analyses (e.g. Wong and Cheng Citation2020). Given the unique characteristics of salespeople, our focus in the subsequent section will center on research specifically pertaining to the retention of an individual salesperson.

One of the most pivotal factors affecting retention is linked to the compensation and incentives provided to salespeople (Rosenberg et al. Citation1981). When salespeople perceive their pay as unfair, they are more inclined to leave the organization (Brashear, Manolis, and Brooks Citation2005). Given the direct association between pay and performance in a sales context (e.g. Ahearne, Mathieu, and Rapp Citation2005), numerous studies have delved into the role of performance for turnover. In this regard, Sunder et al. (Citation2017) showed that relative performance, customer satisfaction, and goal achievement can reduce turnover intentions (i.e. to an individual’s desire to quit the job; Chen et al. Citation2011). Other studies found a link between higher performance levels and diminished turnover intentions or identified moderating effects of performance levels (Futrell and Parasuraman 1984; McNeilly and Russ Citation1992; Russ and McNeilly Citation1995; Rutherford, Park, and Han Citation2011).

Nonetheless, beyond the "hard" economic aspects (including financial and performance-related factors), soft elements, such as relationship quality or stress, may also impact the retention of salespeople (Hartmann and Rutherford Citation2015; Kraft, Maity, and Porter Citation2019; Rosenberg et al. Citation1981; Westbrook and Peterson Citation2022). In connection with this, a wealth of studies has underscored the pivotal role of stress in influencing salespeople’s intentions to leave their positions (Boles et al. Citation1997; Jaramillo, Mulki, and Boles Citation2011; Kraft, Maity, and Porter Citation2019; Speier and Venkatesh Citation2002). Role stress is primarily described across three dimensions: role conflict, role ambiguity, and work overload (Barsky et al. Citation2004; Jaramillo, Mulki, and Solomon Citation2006; Singh Citation1998). This topic is of particular relevance to research on salespeople due to their role as boundary spanners, engaging with various parties (Boles et al. Citation2012; Singh Citation1998).

Likewise, the relationships that a salesperson maintains with her/his supervisor and colleagues are crucial (Gabler and Hill Citation2015; Westbrook and Peterson Citation2022). Challenges in this regard include concerns about perceived injustice and trust (Brashear, Manolis, and Brooks Citation2005), a lack of alignment with supervisors or the organization (Mallin et al. Citation2022), or the perception of inadequate support efforts (DeConinck and Johnson Citation2009), all of which can drive salespeople further away from a firm.

Moreover, a plethora of other factors has been associated with salespeople’s intentions to leave. These factors include the perceived ethical climate, which can impact a salesperson’s role stress, job attitudes, turnover intentions, and job performance (e.g. DeConinck Citation2011b; Jaramillo, Mulki, and Solomon Citation2006), as well as how the breach of a psychological contract influences the job attitudes of salespeople (Hartmann and Rutherford Citation2015). Finally, individual differences among salespeople also play a crucial role, affecting, for example, how they cope with stressful situations (Kraft, Maity, and Porter Citation2019; Lewin and Sager Citation2010).

Literature summary

Previous literature has largely delved into SI into NPD, particularly concerning the "hard" economic SI outcomes mentioned earlier. However, the extent to which SI into NPD may impact the "soft" outcomes within organizations, such as salesperson retention, as well as potential mediators touching benefits and costs of SI into NPD for salespeople, remains unclear.

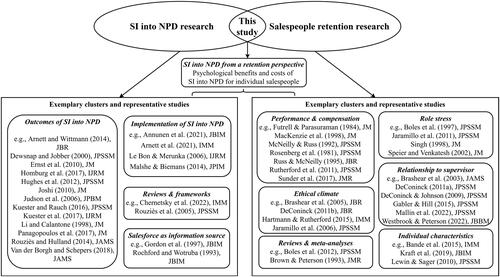

Conversely, a substantial body of literature exists on factors and mechanisms driving salesperson retention in a general sense, offering hints about potential mediators or mechanisms through which SI into NPD might influence salesperson retention. Nevertheless, whether these findings apply to such a context is yet to be explored. Consequently, the goal of our study is to construct a framework that illuminates this significant yet under-researched topic. summarizes the key literature fields and how they relate to our study. In addition, we added as a positioning Table (e.g. Schmitz et al. Citation2020) to further highlight the essence of our study.

Table 1. Positioning of the focal study.

Overall approach for the conceptual development

Due to the limited research on the link between SI into NPD and salesperson retention as well as the potential underlying positive and negative mechanisms, our framework development and propositions will be rooted in a qualitative study using a grounded theory approach. Throughout this process, we will also explore potential situational factors that may influence and shape the relationship between SI into NPD and salesperson retention.

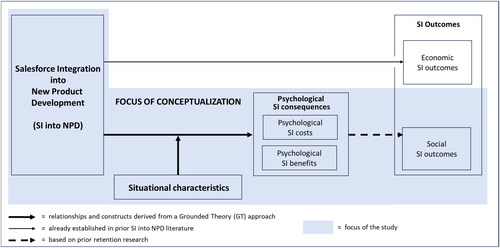

shows the initial conceptual framework based on existing knowledge of the impact of SI into NPD on salesperson retention. Our unit of analysis is a specific NPD integration scenario for a salesperson within a particular company. The shaded area within the base framework represents our primary focus in conceptualization. Although we will not develop propositions concerning economic SI outcomes, as these have already been extensively explored in the literature, we have included them in the base framework to provide a comprehensive view on the outcomes of SI into NPD.

The focus outcome of our framework is salesperson retention, which we define as the willingness of a salesperson to remain with his/her organization (Allen, Bryant, and Vardaman Citation2010; Boles et al. Citation2012). However, the relationship between SI into NPD and salesperson retention seems multifaceted. A base for exploring these facets is to take on a job demands-resource (JDR) perspective (e.g. Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Demerouti et al. Citation2001; Kuester and Rauch 2016). In line with this theory, SI into NPD activities can be considered as the job demands that require “sustained physical and/or psychological effort” (Zablah et al. Citation2012, 21), while the resources provided can enhance employees’ motivation. Assuming that SI into NPD is primarily related to psychological (in contrast to physical) efforts, these demands may ultimately trigger certain outcomes for each salesperson. These may be both positive (benefits) or negative (costs), depending on the resources that a salesperson has available, such as in terms of time (e.g. more or less time depending on other tasks or the number of customers), goal flexibility (e.g. potentially conflicting goals) or the like.

In broad terms, we label these potential outcomes as psychological SI consequences in terms of psychological SI benefits and SI costs. The general differentiation of these types of consequences is rooted in prior literature of different fields (e.g. Hartmann and Apaolaza-Ibáñez Citation2012; Larkin, Pierce, and Gino Citation2012). Typically, psychological SI costs relate to an unpleasant inner state of tension and uncertainty resulting from different types of negative feeling and perceptions (Karakaya 2000; Larkin, Pierce, and Gino Citation2012), while psychological SI benefits describe a pleasant state of emotions stemming from positive feelings of different types (e.g. Brown et al. Citation2005; Ryan and Deci Citation2000). The specific nature associated with these benefits and costs in the context of SI into NPD, as well as their interconnections with SI into NPD and salesperson retention, will be developed through our qualitative study.

Definition of SI into NPD

The concept of SI into NPD has been considered from different perspectives and builds on the general construct of cross-functional integration. Specifically, Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen (Citation2010) point to the two dimensions related to SI into NPD: an attitudinal perspective (see also Kahn Citation1996), focusing especially on mutual goals, understandings, and visions of the team members (including the involved salespeople) as well as the behavioral perspective (see also Kuester, Homburg, and Hildesheim Citation2017), considering the “level of interaction and information sharing between members from different departments” (Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen Citation2010, 81). Interestingly, prior research has demonstrated as well that both, attitudes and behaviors (of oneself and others) may affect salesperson retention (Boles et al. Citation2012; Jaramillo, Mulki, and Boles Citation2011; Sunder et al. Citation2017).

Therefore, we opted for integrating these views into our definition of SI into NPD, supported by views from previous literature (Ernst, Hoyer, and Rübsaamen Citation2010; Kuester, Homburg, and Hildesheim Citation2017). Specifically, we define it as the extent to which a salesperson is involved in an NPD project by its company and is enabled and motivated to contribute customer- and market-specific insights for further use throughout the NPD project.

Conceptualization of the link of SI into NPD on salesperson retention

In this section, we will initially outline the methodology of our qualitative study. Subsequently, we will utilize the insights garnered from this qualitative study to construct our framework and formulate propositions, employing a grounded theory approach.

Methodology

Numerous studies suggest that for investigations in areas lacking theoretical frameworks, a qualitative method holds great promise (Corbin and Strauss Citation1990; Creswell Citation2007; Johnson Citation2015) as this approach “allows for a more discovery-oriented approach in conducting research and can be particularly useful in exploring phenomena where little understanding exists” (Johnson Citation2015, 262). Consequently, we opted for a qualitative study, following a grounded theory approach, to gain a thorough understanding of the connection between SI into NPD and salesperson retention. In this section, we outline our methodological approach, and subsequently, we delve into the conceptualization of the link between SI into NPD and salesperson retention, while also exploring potential situational factors.

A grounded theory approach

We adopted the grounded theory (GT) research approach (Johnson Citation2015), which has been extensively applied in sales literature. Following Johnson (Citation2015), we justified our method, outlined research questions, explained the sampling and data collection methods, provided details about the interviews, data volume, and described the data analysis, including coding schemes, software usage, and the incorporation of quotes to substantiate our statements. Similar decision pathways have been identified in various recent studies (e.g. Johnson and Matthes Citation2018; Johnson and Sohi Citation2016; Malshe et al. Citation2017; Malshe and Krush Citation2021; Malshe and Sohi Citation2009; Paesbrugghe et al. Citation2020).

To explore the role of SI into NPD for salesperson retention, we collected data from individuals who have firsthand experience with SI into NPD, as only they can provide suitable assessments owing to their personal experiences. To do so, we conducted comprehensive in-depth interviews with sales managers who were involved in SI into NPD previously and were supervisors of salespeople who did. As such, they are well-positioned to comprehend both the employee and organizational perspectives in this context. Our goal was to illuminate potential positive and negative consequences in terms of psychological SI benefits and costs, as well as situational factors that may affect the impact of SI into NPD on a salesperson retention.

Data collection and sample

Data for this study were gathered through in-depth interviews with 11 sales managers from various industries in a B2B context. outlines the interviewees’ profiles. We enlisted our informants by reaching out to a prominent sales association in a central European country, disseminated our request and criteria to their members. We ensured that all companies of the sales managers in our sample had distinct sales departments. Our approach followed a theoretical sampling method, as utilized in prior studies, which is particularly suitable when specific experiences are sought for research purposes. This method has been employed in numerous related studies (Johnson and Matthes 2018; Malshe et al. Citation2017; Malshe and Krush Citation2021). Interview scheduling commenced in July 2023, with the interviews conducted between August and October 2023. Interview durations ranged from 30 to 50 min, and we concluded the interviews upon reaching theoretical saturation, following recommendations from several studies (e.g. Creswell Citation2007; Johnson Citation2015).

Table 2. Profiles of our interview partners.

All but one interview took place online, with one conducted via Microsoft Teams, while the others were carried out using Zoom. We recorded the audio of each interview and transcribed them using the Whisper API (Application Programming Interface) from OpenAI. The automatically transcribed texts were subsequently manually proofread, and errors were corrected. During the interviews, we prepared several guiding questions based on the findings of our literature review (see the Web Appendix). However, we encouraged participants to speak openly about their experiences and incorporate real examples when they felt it would enhance the context and depth of their responses. Our intervention was limited to seeking clarification or transitioning to another topic to minimize content bias.

Data analysis

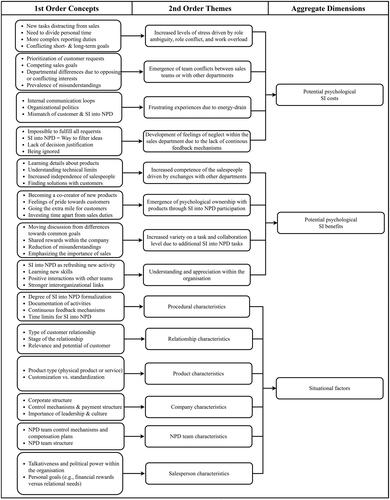

We utilized NVivo qualitative data management software to handle the interview data (Malshe and Sohi Citation2009; Paesbrugghe et al. Citation2020). The initial coding scheme was developed by the authors. In line with previous research, we employed a multi-stage coding process, starting with descriptive first-order codes and then clustering them into second-order themes aligned with theoretical concepts. These themes were subsequently mapped to aggregated dimensions (i.e. psychological SI costs and SI benefits, along with situational factors), as recommended by relevant studies (Corbin and Strauss Citation1990). The data analysis unfolded iteratively, with continuous reviews of the codes throughout the analysis phase. This iterative approach allowed us to identify new categories and apply insights to the coding of subsequent interviews. Our theoretical framework emerged from these higher-order themes ().

We ensured that the coding process during the analysis stage was not influenced by preconceived categories, following the advice of Gummesson (Citation2003). Additionally, we sought feedback from an independent researcher and a sales executive who were not part of this study. displays the first-order codes, second-order themes, and the identified aggregated dimensions. Subsequent sections detail the aggregated dimensions and their categories, supported by quotes from the interviews, which ultimately result in our final framework.

Study results: key formats of SI into NPD in the companies of the interviewees

It became apparent that SI into NPD comes in various forms of activities. Basic variants include customer request forms and salespeople surveys covering market developments, customer churn reasons and ideas that could help salespeople better serve their customers. Some firms also used cloud-based software solutions to collect and update these ideas continuously.

Several firms also relied on more interactive and regular formats such as weekly and well documented meetings within the NPD team including the assigned salespeople. Less regular interactive formats included team workshops or innovation days with customers and salespeople. Another approach was to generate initial product proposals through the marketing department and to frequently discuss them with representatives of the sales department. Some firms assigned test customers to salespeople in NPD teams, who then evaluated new prototypes before going into more in-depth conversations with the broader customer base. Most firms also used the opportunity to build interdepartmental NPD project teams including pre-selected salespeople.

Study results: the nature of psychological SI costs and its link to SI into NPD

All interviewees agreed that SI into NPD may come at the expense of the salesperson involved in an NPD project owing to a variety of challenges, thus causing negative consequences for that particular salesperson. Our study interviews uncovered a broad spectrum of these challenges, with the most prevalent being role stress, team conflicts, frustration, and feelings of neglect. We discuss them in the following sections, drawing on interview quotes and findings form the literature.

SI into NPD and role stress

In line with prior literature, role stress refers to the stress associated with a salesperson’s job and relates to three dimensions: role conflict (i.e. the degree to which a salesperson perceives conflicting expectations and demands, such as from supervisors vs. customers), role ambiguity (i.e. the perceived lack of information necessary for a salesperson to perform their role effectively and the uncertainty regarding the expectations of various role set members) and role overload (i.e. a salesperson’s belief that the combined role demands exceed their abilities to fulfill a task) (Barsky et al. Citation2004; Jaramillo, Mulki, and Solomon Citation2006; Singh Citation1998). Our interviews reveal that SI into NPD may trigger role stress through creating a conflict with a salesperson’s goals. That is because SI into NPD may extend sales employees’ existing workload by requiring them to allocate their limited time to a new activity. This reduces the time a salesperson can devote to customers and thus her/his own sales performance:

“Well, the overall customer facetime is obviously reduced through our sales-tech meetings. But we first need competitive products before we can go out and try to sell something – and that is why we (sales department) need to take part in the development process. I think the key here is to communicate this overarching goal.” [2]

“[…] these activities are, of course, also very much in need of explanation. And if I always have to explain why I am suggesting something, and that’s how it is when you think from the customer’s point of view, it costs much time and energy. The sales guy reports a request and says something like: ‘Hey developer, we need to think about this and that because the customer would like this more.’ And then the discussion starts. This is why they often ask, why do we have to do this now as well when we have so much else to do?” [9]

SI into NPD and experiences of frustration

In addition, interviews indicated that a salesperson engaging in SI into NPD may also experience frustration (i.e. a personal interference with a goal-oriented activity, such as SI into NPD; Spector Citation1978), leading to negative outcomes. This is especially the case when only a limited number of a salesperson’s ideas or customer requests can be integrated due to resource constraints or conflicting company goals and perhaps even suboptimal communication exist (see also Sabnis et al. Citation2013):

“I would say that our weekly tech exchanges are the foundation of our success since they help us being very close to the market. They are a way to consolidate all of the requests and to identify reoccurring topics, distinguish real bugs from unsophisticated ideas etc. However, I also experienced that this can easily lead to severe frustration and misunderstandings, for example if someone brings in a lot of ideas and nothing of it ever finds a place on our software roadmap.” [4]

SI into NPD and feelings of neglect

Another key point from the interview relates to the observation that not every salesperson engaging in SI into NPD may experience tangible outcomes as not all request may be fulfilled:

“We do not sell individual software which differs from client to client. We only sell standardized software and cannot just develop features that would make some of our 3000 clients very happy but likely cause issues or lead to no benefits at all for the other 2800. The thing is, the requests that get fulfilled will have significant impact but making this clear to everybody is a challenge. This really was a learning experience for everyone involved and who reported customer feedback I think.” [4]

“Also, what I have experienced is that when sales colleagues or customer service colleagues come up with some issue from a customer, it gets played back and forth forever […]. Of course, it makes one tired. But creating a platform, co-creation workshops […] everything that moves more towards collaboration, that relieves the representatives, does them good.” [7]

SI into NPD and team conflicts

Another learning from the interviews was that fulfilling one customer request often meant that the NPD team could not fulfill other customer requests due to their limited number of engineers, leading to conflicts between the NPD team members. Following prior work, we refer to these conflicts as negatively charged social interactions between a salesperson and her/his coworkers in an NPD team (Jaramillo, Mulki, and Boles Citation2011; Spector Citation1987). In one case, conflicts arose even between different sales teams. One team closed a substantial deal and had a very satisfied customer, while the other team had to explain to their customers why their requests could not be fulfilled while deadlines were not met:

“We certainly experienced conflicts between teams caused by this but noticed them rather late since some competitive atmosphere is probably normal between teams. For example, we invested our resources into one large customer request which meant we could not do anything for another, arguably equally important, customer. It made sense from a business standpoint at the time but it was very hard to communicate this internally, many considered this unfair – like delighting one customer while failing to meet deadlines for other customers.” [9]

“Well, I think our sales and development teams have very different goals. Sales wants to make deals while the engineers need to be on time with their product roadmap, which is already hard enough without such individual requests. The requests coming from salespeople are just additional work for them. I experienced conflicts about simple renderings in a new color or so. I mean, we deal with humans after all. And these parties do not always agree with each other in terms of what request is how important, how much time fulfilling the request will take and this often creates a lot of tension, sometimes even organizational politics.” [2]

Overall, we find that SI into NPD can entail substantial psychological SI costs for a salesperson, specifically role stress in all its facets, frustration, neglect, and conflicts, making it a delicate balance:

Proposition 1:

SI into NPD can lead to negative psychological consequences in terms of psychological SI costs, which involve an increase in role stress, frustration, perceived neglect, and team member conflict.

Study results: the role and nature of psychological SI benefits

Besides psychological SI costs, our interviews also revealed numerous potential benefits of SI into NPD. We will categorize these benefits into themes related to salesperson’s perceived competence, psychological ownership, appreciation for the salesperson, and task variety.

SI into NPD and perceived competence

Many managers expressed a consensus that SI into NPD significantly enhanced the perceived competence of their salespeople (i.e. the feeling of being effective with respect to reaching a certain objective such as improving a product for one’s customer in the context of SI into NPD; Ryan and Deci Citation2000), subsequently boosting their motivation and commitment to tasks. To achieve this, the salesperson needs to actively engage in these SI activities and to proactively engage with her/his NPD team members:

“Our weekly exchanges made our salespeople much more competent with regard to their technical know-how. At least some of our “tech guys” are always present in these meetings and explain why some things need to be done a certain way, why some things are simply not possible […] and so on. Then, our salespeople can explain such things on their own when talking to customers and even use it when they try to figure out new solutions with them. And I am sure they are very happy about that, although we never explicitly measured this.” [4]

“What I expect from my employees is not to be tech experts, I don’t think that is necessary at all to be able to sell our products. But I expect that they can translate the customer requests into specifications that our engineers understand, to be a good middleman. And they learn to do that much faster when they are involved in our development meetings, when they talk about it and not just sell it. It makes communication much, much easier. We do less mistakes and they probably feel more independent as a result since we do not have to always send engineers with them.” [3]

SI into NPD and psychological ownership

Another theme from the interviews relates to the relationship salespeople build with the products they co-develop in terms of perceived psychological ownership, which we define as the degree to which a salesperson feels that the target of ownership (i.e. the new product) is her/his achievement (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001; Pierce, Rubenfeld, and Morgan Citation1991). Sales managers noted that their team members developed a deeper appreciation for products when they could influence them during NPD. For instance, one manager mentioned that salespeople who participated in an NPD project expressed feelings of pride after gaining technical knowledge about products that they could use during customer interactions.

“If they (salespeople) are involved early on when we develop new products, they become a co-creator that basically knows everything about the product. And then they are obviously more proud and confident when they go out and try to sell this product. Even more so if it was based on a customer request that they successfully moved across the finish line for their customer.” [5]

Expanding on this theme, one manager went as far as to say that the effort that salespeople invest in the development of new products essentially make the new product their “baby”. They feel a sense of co-creation with the product, rather than just selling another item thought up by someone in the organization as a good fit for target customers and the market.

“[…] because it’s their baby, they have co-developed it. They had a say in it, so to speak. They could incorporate their ideas into it and are now passionate about it. And if they are passionate about it and stand behind it, they will love to sell it.” [6]

SI into NPD and appreciation

Apart from these individual-level benefits, managers repeatedly stressed the importance of appreciation that a salesperson may experience from SI into NPD (i.e. the perception that others value the salesperson’s efforts or achievements in NPD; Pfister et al. Citation2020; Stocker et al. Citation2019). A close SI into NPD may substantially improve the perception of the involved salesperson per se and of the sales team within the firm overall. A key cause for these positive changes was the shift in focus among NPD team members from individual goals to larger company goals, highlighting the crucial role of salespeople:

“I experienced that this [SI into NPD] strengthened the standing and the perception of our sales department quite strongly. Especially our developers understood that they (the salespeople) are not just the ones who are running around and who you can’t get a hold of. They saw that the sales guys are the ones who are really working together with them on the added value of the organization, that they are a large team after all and that the sales guys bring in the money, that they just want to make sure we sell the right thing and not just command them around.” [7]

“[…] otherwise they wouldn’t know what something is actually for, why they are working on this particular thing or why something just makes no sense from a technical point of view. Like the next iteration of the design of a particular plug for example that someone wants. They can also see that the requests are not put by some salespeople or supervisor on their table, but that this is rather something that the customer put on the table of the organization through the salespeople they are in contact with.” [7]

SI into NPD and task variety

Moreover, we discovered that SI into NPD can enhance task variety for a salesperson, both in terms of tasks and collaboration. In line with Hackman and Oldham (Citation1976), we define task variety as the extent to which SI into NPD enriches the variety of tasks that a salesperson needs to fulfill. As one manager explained, SI into NPD can be a breath of fresh air for a salesperson’s task portfolio:

“I’d compare it to other extraordinary activities that our employees can engage in, for example guest lectures, attending fares or being a mentor for younger employees and interns. It is basically a change of scenery which can sometimes help recharge the batteries. And it also “forces” you to meet new people which our salespeople usually like since they are pretty outgoing.” [7]

“I think it is really important to think of solution selling instead of just product selling […] and creating a platform, whether it’s through a customer focus group or through co-creation workshops or through other means, like prototyping together with the customer, applying design thinking methods, basically anything that leans more towards collaboration, is great in general.” [7]

Proposition 2:

SI into NPD can lead to positive psychological consequences in terms of psychological SI benefits, which involve an increase of perceived competence, psychological ownership, task variety, and appreciation.

Study results: conceptualization of situational factors

The interviews revealed that success and failure of SI into NPD can vary with various situational factors. We will introduce and elaborate on them in the following sections. Specifically, as will become clear from the interviews, SI into NPD may affect psychological SI consequences to different degrees depending on certain characteristics of the company, the NPD team, the salesperson per se, the procedure of its implementation, the relationship with the respective customers, as well as the developed product. Again, this general notion can be well explained from a JDR perspective which suggests that both demands as well as resources may have mutually moderating impacts on their outcomes, such as psychological SI costs and benefits (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Zablah et al. Citation2012).

The role of company characteristics

During the interviews, it became clear that having a leader who backs the sales team during NPD activities and thus showing a supportive leadership style is crucial. As a sales manager states:

“You definitely need a strong leader for this. The conflicts are always going to be there. But I’d say that this is a good thing and perhaps conflict is not the best word for it. It is some sort of challenging collaboration. But you need someone to guide people, lead the hard communication and sometimes even protect employees from unhappy customers or other departments.” [2]

“You first need to get people do it. And then you need to make sure they keep doing it. So I think it is the supervisor […] who needs to communicate why these processes are so important for the company. But you also need to intervene when things are not working as intended.” [1]

“They are already incentivized because if they want to get the deal/provision, they need to bring the customer requests across the finish line anyways. It is necessary for them to take part in the development process.” [7]

“If everyone simply receives an individual provision which was negotiated based on personal goals, then he or she will also work and act accordingly. No matter how he or she is wired in terms of organizational identification, team spirit etc. I would say.” [6]

The role of NPD team characteristics

According to the interviewees, it is essential to recognize that interpersonal dynamics can also vary within an NPD team, and not all teams function equally well, as the following statement shows:

“I think it all plays together, like the payment structure, how you assign project teams, if you are celebrating successes of new products together as a team or rather as an individual and so on. And, of course, how you deal with all the potential issues that can occur.” [6]

The role of salesperson characteristics

Furthermore, individual differences among salespeople can be crucial to leverage SI into NPD’s impact for retaining them. Some salespeople may have better networks or relationships with engineers, which improves their opportunities to fulfill their customer requests. This “political element” appears to be somewhat typical for processes related to SI into NPD:

„You always deal with people after all. There will always be some sort of interpersonal dynamics going on which you can limit through these processes. We make sure that the exchange of ideas takes place directly, not indirectly through some third-party inside of the company. That is good because sometimes ideas get lost in the hierarchies for political or whatever reasons […] or some ideas do not really want to be heard or are simply not forwarded to the right people etc.“[7]

“I am not a fan of assigning all of my people to these tasks. I generally just talk to them and try to figure out what their interests are and then I can adjust the personal goals. For example, some members of the sales team act as promoters of these internal processes, help manage it [SI into NPD] while others have more revenue expectations. Not everyone has to do everything.” [8]

The role of procedural characteristics

Another major factor in this regard relates to the design of SI into NPD processes. While the exact institutionalization of SI into NPD activities varied among the companies, all managers stressed the importance of procedural characteristics. They may especially relate to elements such as a clear process formalization (such as NPD taskforces or customer innovation days), comprehensible documentation (such as standardized customer request forms), regular feedback loops (such as weekly meetings), or defined time limits per meeting (such as one hour per SI meeting).

When processes of SI into NPD are clearly structured along such well-defined characteristics, it helps the involved salespeople structure and execute their NPD and customer-related activities more effectively and efficiently. In being enabled to share and apply their knowledge for NPD in a more effective and efficient way, salespeople may experience less role ambiguity and workload:

„It was a very little time investment by everyone that lead to huge benefits. Our structure, in this case weekly meetings between sales, service, tech, and marketing, predefined when and how much time had to be invested as well as what the exact outcome was. As a result, the exchange is, I believe, never going beyond the scope of available resources, let’s put it that way.” [10]

“I would say that it (the SI into NPD process they established) even reduced stress to some extent. I mean when you know that you will talk to someone from the tech department anyways in two days or so, so you do not need to try to get a hold of him, prepare a mail or so when you have better things to do. It gives some kind of structure.” [11]

“At the beginning, we are indeed consulted. However, during the development process, which can sometimes take up to two years for us, we are not involved if we don’t take the initiative ourselves. At least, we can’t be certain that we will be included. And we experienced that some adjustments were made during development before that completely disregarded what the customer actually wanted and what was discussed. It was a relatively small adjustment for the developers in that case, but that made a huge difference for the customer. Keeping this dialog (across NPD activities) alive over such a long time is both necessary and challenging I think.” [1]

The role of relationship characteristics

Moreover, all interviewees pointed to the need to consider the specific relationship that salespeople have with their customers. This may involve its relevance, its type (e.g. product or service), and its stage (e.g. early vs. established). For example, interviewees noted that encouraging a salesperson to engage in substantive discussions about new products or solutions with smaller clients may enhance his/her frustration owing to spending time with a client that may not even value the efforts. A senior sales executive in the industrial machines sector highlighted this situation as follows:

“[…] what course of action should our sales team take when they are primarily tasked with selling standard products straight from a catalog? When they align precisely with the customer’s wants and needs? I am sure initiating discussions about innovations or new operational processes under such circumstances would only lead to frustration on both sides.“[9]

„Once won, you rarely want to lose important customers again. Fulfilling these individual requests sends positive signals towards our customers and this improves the business relationship […] but when to invest these efforts certainly depends on the size of the respective customer.“[10]

„These (requests and ideas by bigger customers) are often much more sophisticated requests where some workarounds within the software have been tried beforehand or so and where actual limits and deficits of the software have been identified.” [5]

The role of product characteristics

Besides considering specificities of the individual customers, also the industry as well as the specific type of the product may determine how strongly SI into NPD may drive a salesperson’s psychological SI benefits and costs. This consideration aligns with views of several managers who link the nature of a product to the actual effectiveness of SI into NPD. In particular, one manager emphasized potential over-engineering in case of having a product that satisfies the market sufficiently:

“When we have a great product-market fit for a specific solution and I can win clients very well with it, then it might be more important to make use of this momentum instead of thinking about innovating even further, at least at this point in time.” [6]

Moreover, not all products require individualization as there may be a sufficiently high number of customers being totally fine with the benefits that standardized products provide. In such a case, forcing a salesperson into SI into NPD activities may be emotionally draining for all parties involved – the salesperson not being able to engage in her/his actual sales activities and the customer not understanding as to why a perfectly fitting product needs enforced optimization:

“I don’t think I can expect all of our salespeople to collect customer ideas, to rethink their processes etc. Many of our clients are perfectly happy with the “catalog products” that we sell and making our salespeople force conversations about innovative processes or solutions could quickly become a waste of time and energy for everyone involved.” [9]

Consequently, and in line with the JDR perspective, if leveraged and utilized adequately in a specific context, the situational characteristics will help salespeople cope with the demands of SI into NPD, while at the same time make even better use of the provided resources. Thus, we predict:

Proposition 3:

The extent to which SI into NPD activities affect psychological SI benefits or SI costs depends on a variety of situational factors. In particular, these are company characteristics, NPD team characteristics, salesperson characteristics, procedural characteristics, relationship characteristics, and product characteristics.

Psychological SI costs and benefits on salesperson retention

In this section, we link the psychological SI consequences to salesperson retention. We will do so by relying on general work on employee retention and turnover (e.g. Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner Citation2000; Hom et al. Citation2017; Porter and Steers Citation1973) as well as specific work on salesperson retention (e.g. Boles et al. Citation2012).

The impact of psychological SI costs on salesperson retention

The negative impact of psychological SI costs, such as role stress, on turnover intentions or employee retention is well supported in the literature (Chandrashekaran et al. Citation2000; Fisher and Gitelson Citation1983). The interviews supported these general notions and revealed that stress resulting from SI into NPD related work overload, role ambiguity owing to lack of clarity on how to prioritize SI into NPD, and role conflict with personal selling goals can play their part in impacting a salesperson’s intention to quit, particularly as salespeople typically operate in a very stressful environment (Singh Citation1998). In line with activation theory (Malmo Citation1959; Scott Citation1966), the potential addition of even more stress through SI into NPD and the described negative consequences (SI costs) may lead to an exceedance of an acceptable stress level for a salesperson, thus reducing her/his retention (Scott Citation1966; Singh Citation1998).

Salesperson retention is further likely to be affected by SI into NPD-related team conflicts, which can, for example, be related to feelings of injustice. These have been repeatedly linked to intentions to quit (Hausknecht, Sturman, and Roberson Citation2011; Hom et al. Citation2017) and equity theory (Adams Citation1965), where “contributions (i.e. made by a salesperson in the context of SI into NPD) to his or her organization are termed inputs and the rewards received from an organization are termed outcomes” (Arnold et al. Citation2009, 62). For example, when in an SI into NPD context NPD requests of some salespeople are fulfilled but those of others are not, a perceived lack of fairness can occur since the rewards the “lucky” salesperson receives are higher than those receive whose request have not been fulfilled, whilst the costs of all of the salespeople (efforts put into SI into NPD) involved in the overall process remain comparable.

Moreover, the energy-draining communication loops between NPD-involved people and the resulting frustration can cause emotional exhaustion of salespeople. This depletes energy from salespeople that could have been used for other important tasks and lead to work overload as well since more time than necessary (or previously planned) has to be spent on these activities. Both emotional exhaustion and work overload have been previously linked turnover (e.g. Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner Citation2000; Wright and Cropanzano Citation1998), thus reinforcing the proposed mechanism.

The highlighted potential feelings of neglect can also be related to factors that impact salespeople turnover. If salespeople are expected to engage in SI into NPD activities with their customers, but do not receive adequate feedback on their efforts, it represents a lack of support already known to serve as a major antecedent of turnover (DeConinck Citation2011a; DeConinck and Johnson Citation2009). Thus:

Proposition 4:

Psychological SI costs (specifically role stress, frustration, team conflicts, feelings of neglect) can substantially reduce salesperson retention.

The impact of psychological SI benefits on a salesperson’s retention

Interviewees stressed enhanced competence as a key benefit for a salesperson from participating in SI into NPD. This, in turn, enables a salesperson to provide more comprehensive and independent assistance to customers apart from a firm’s developers. Through increasing their intrinsic motivation (i.e. “doing an activity for its inherent satisfaction”; Good et al. Citation2022, 588) according to self-determination theory (e.g. Ryan and Deci Citation2000) and consequently job satisfaction (Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner Citation2000; Hom et al. Citation2017) as well as a salesperson’s goal performance (Good et al. Citation2022), the increased level of perceived competence can reduce turnover intentions (Rutherford, Park, and Han Citation2011; Sunder et al. Citation2017).

Furthermore, managers underscored the pride their sales employees felt when presenting fulfilled customer requests to their clients. Moreover, they exhibited a profound sense of ownership after participating in SI into NPD activities. Such participation not only grants employees the belief that they can influence the company’s future but has also been extensively linked to employee retention and positive job attitudes (Bakan et al. Citation2004; Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner Citation2000; Grissom Citation2012).

Enhanced appreciation can translate into a higher identification of a salesperson with the NPD team and the company according to social identity theory (Ashforth and Mael Citation1989; Mael and Ashforth Citation1992), with identification defined as “perceived oneness with an organization and the experience of the organization’s successes and failures as one’s own” (Mael and Ashforth Citation1992, 103). This, in turn, can result in a stronger focus on collective team and company objectives, thereby enhancing satisfaction and organizational commitment, fostering a salesperson’s retention (Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner Citation2000; Meyer, Becker, and Van Dick Citation2006).

Finally, higher task and collaboration variety, fostered by SI into NPD, is a critical factor that can positively impact job attitudes (Hackman and Oldham Citation1976). By engaging in SI into NPD, a salesperson gains exposure to new tasks, skills, and collaborates with diverse colleagues. This fosters a sense of integration and yields positive job outcomes, which can lower turnover intentions (Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner Citation2000; Mitchell et al. Citation2001). Overall, we thus propose:

Proposition 5:

Psychological SI benefits (perceived competence, psychological ownership, task variety, and appreciation) can substantially enhance salesperson retention.

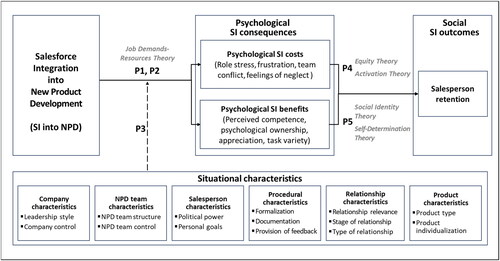

Drawn from our qualitative study and the associated grounded theory approach, we present our final framework proposition (please refer to ), which we will explore in the following section.

Discussion

Researchers have repeatedly emphasized salespeople as a valuable source of (tacit) market information on NPD (e.g. Judson et al. Citation2006; Rochford and Wotruba Citation1993) and have demonstrated that their integration into NPD can enhance economic SI outcomes, such as adoption or performance of new products (e.g. Joshi Citation2010; Kuester, Homburg, and Hildesheim Citation2017). However, SI into NPD’s impact on salespeople themselves, as well as their related social SI outcomes and ultimately salesperson retention, remains largely unexplored. Consequently, we investigated this critical topic through a qualitative study following a grounded theory approach.

Research implications

The core output of our study is the conceptual framework (see ) assuming that SI into NPD can impact a salesperson’s retention through affecting her/his perceived psychological SI benefits as well as psychological SI costs, while it is crucial to consider various situational factors. Thus, this qualitative study and the resulting conceptual framework underscore the complexity of SI into NPD’s role in shaping social SI outcomes and specifically a salesperson’s retention to the firm. It suggests that SI into NPD can act as a connector to attract salespeople more strongly to a firm if done right and psychological SI costs are under control and psychological SI benefits are fostered, but also repel them if it is mismanaged or situational factors are ignored.

Thus, the framework suggests that SI into NPD may be a double-edged sword with regard to maintaining key contributors to the firm, i.e. salespeople. In this regard, this study also extends previous work that investigated SI into NPD from a JDR perspective (e.g. Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Demerouti et al. Citation2001; Zablah et al. Citation2012), which helps explain the observations made in the interviews with regard to the impact of SI into NPD on psychological SI consequences.

Negative psychological consequences of SI into NPD: the role of psychological SI costs

Psychological SI costs can result from multiple sources, of which we identified four. Feelings of frustration and neglect by salespeople, for instance, primarily result from experiences within their own role, often associated with the struggle to meet the daily expectations placed on them, including routine tasks typically handled by salespeople and the associated communication. In contrast, conflicts within the NPD team tend to arise mainly due to disagreements with team members from different departments, notably driven by a lack of consideration for customer needs by those parties. The primary stressors, on the other hand, largely originate from the nature of the tasks themselves, particularly due to an unclear integration of the new responsibilities with salespeople’s primary tasks in terms of role ambiguity and the overall workload. By nature, negative SI consequences in terms of psychological SI costs are likely to diminish salespeople’s loyalty to their company. For instance, they may feel exhausted due to ongoing conflicts with NPD team members or the additional workload resulting from NPD-related tasks.

Our findings also contribute to prior indications that conflicts with other colleagues and perceived role ambiguity may reduce a salesperson’s motivation to engage in market intelligence activities (e.g. Kuester and Rauch 2016). In particular, our study supports this view, further links this notion to salesperson retention, and adds additional context through the content of the interviews.

Positive psychological consequences of SI into NPD: the role of psychological SI benefits

Furthermore, we also found that SI into NPD may lead to psychological SI benefits, which previous research has not considered so far, and which may cause a salesperson to be more likely to stay with her/his employing firm. Specifically, we identified four key dimensions in this regard: perceived competence, psychological ownership, appreciation, and task variety. The interviews clearly suggested that only because some negative consequences of SI into NPD giving salespeople “more reasons to leave the organization” can occur, this does not rule out the possibility of potential SI into NPD upsides that may give salespeople “more reasons to stay”, including higher levels of competence, psychological ownership, appreciation, and task variety. This consequently adds to developments in turnover research that started to differentiate between the psychology of staying and the psychology leaving (e.g. Hom et al. Citation2017; Jiang et al. Citation2012; Mitchell et al. Citation2001).

Our study further suggests that there are also important nuances to consider. For example, task variety may co-occur with some degree of role ambiguity, particularly in the context of SI into NPD where new tasks differ substantially from making product sales. As task variety can positively affect job attitudes according to the job characteristics model (Fried and Ferris Citation1987; Hackman and Oldham Citation1976), and thus a salesperson’s willingness to stay with the current employer, while role ambiguity (and thus role stress) fosters related costs (e.g. Boles et al. Citation1997; Jaramillo, Mulki, and Boles Citation2011; Singh Citation1998), it is vital to observe which of these two impacts is stronger with regard to SI into NPD

Moreover, SI into NPD requires investments of time and energy from salespeople and can thus add to work overload. However, the time salespeople spent on these SI into NPD activities is largely related to tasks conducted together with other people (e.g. within NPD teams). The results suggest that this helps salespeople, who are often rather isolated owing to their frequent travel or customer-located activities, build new links within their company, potentially resulting in them being more embedded within the organization (e.g. Mitchell et al. Citation2001).

The role of situational characteristics

Our interviews revealed six groups of characteristics pertaining to the company, the NPD team, the salesperson themselves, the implementation procedure, customer relationships, and the developed product. The extensive array of identified situational factors underscores the considerable complexity and interdependencies involved in the context of integrating SI into NPD.

While we cannot delve into all aspects of the individual moderating impacts in detail here, it is noteworthy that the general logic behind these characteristics warrants exploration, closely linked to the JDR model (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007; Demerouti et al. Citation2001). Our interview results suggest that the demands imposed by SI into NPD (such as additional time requirements) and related resources (such as effective team collaboration) may not only directly affect a salesperson’s psychological SI benefits and costs but also enhance or reduce the impact of SI into NPD on these psychological consequences.

Therefore, our study emphasizes the observation that integrating salespeople into NPD is essentially a matter of clarifying and minimizing the demands associated with SI into NPD while simultaneously providing sufficient resources to leverage its impact for salesperson retention. This appears particularly worthwhile for firms, especially considering that most of the identified situational characteristics represent factors controllable with regard to new product success (Calantone, Schmidt, and Song Citation1996).

Managerial implications

For managers, particularly those overseeing NPD teams and sales departments, our findings carry significant implications. First, managers must recognize the intangible benefits and costs of SI into NPD. Factors identified through this research should, for example, inform feedback conversations with and performance evaluations of employees. Additionally, organizations should incorporate SI into NPD considerations when recruiting new team members and communicate the SI into NPD culture in a transparent manner in order to align expectations and to mitigate potential future misunderstandings since salespeople retention basically starts during the hiring stage.

In addition to fostering awareness of the dual nature of SI integration into NPD, managers must possess the capability to customize their management approaches to suit the specific requirements of their teams. For example, sales managers overseeing teams with salespeople involved in NPD projects should facilitate open discussions to address any conflicts in goals that may arise, which helps alleviate the risks outlined before. This becomes particularly crucial when NPD involvement demands substantial amounts of additional time, as commonly observed in industries such as machine building or software development. Furthermore, managers should address perceptions of fairness with all affected teams, recognizing that achieving perfect balance in effort distribution across teams is very likely to be challenging in practice. Moreover, NPD team managers should establish clear structures and processes within the NPD workflow to mitigate potential sources of frustration or conflicts with other functions, particularly sales personnel, for example through regular meetings, checklists, forms, or software solutions to manage the SI into NPD process.

Additionally, understanding that SI integration into NPD is an ongoing challenge rather than a one-time event is necessary. It is not sufficient to merely collect ideas from salespeople. Rather, ensuring end-to-end follow-ups to all parties affected is imperative. Our interviews revealed that employees explicitly desire information about the outcomes of their contributions, including whether and how their suggestions were implemented and, if not, the reasons behind it. This feedback not only fosters appreciation, increasing the likelihood of retaining sales personnel, but also serves as a motivational factor for continued engagement in SI integration into NPD activities.

Furthermore, managers, including both sales and NPD team managers, should demonstrate adaptability to specific situations. That is, not all sales personnel may be equally suited for participation in NPD teams. While sales-focused individuals with strict sales targets may not contribute significantly to NPD efforts, open-minded, highly motivated, and product-oriented sales personnel can likely provide substantial value. The latter can likely also take on a liaison role and help gathering insights from within the sales department. Hereby, factors such as customer importance or the stage of development in customer relationships can significantly impact the success of SI into NPD activities as well.

Avenues for future research

Although we emphasized the potential tradeoff or, if managed effectively, the leveraging effect of SI into NPD on both economic and social SI outcomes, only economic outcomes have been empirically examined. Hence, we recommend empirically investigating the social SI outcomes of SI into NPD to gain a more comprehensive understanding of its overall impact on salesperson retention, as well as the underlying mechanisms related to psychological SI benefits and costs including potential interactions. Furthermore, conducting comparisons to assess the individual impacts of SI into NPD on these types of outcomes, particularly in diverse situations (e.g. B2B vs. B2C, or product types), or specific contexts such as selling through influencers (e.g. Schwehm, Prigge, and Schwehm Citation2023), could yield valuable insights. Moreover, it would be intriguing to ascertain the extent to which SI into NPD affects salesperson retention when compared to other pivotal factors, such as compensation levels, especially in the context of the competition for sales talent.

The analysis also revealed that SI into NPD activities can impact the well-being of salespeople, with both positive and negative effects. Notably, as stress levels are on the rise, particularly in sales roles, this topic has garnered increasing academic attention. Previous research has cautioned against the potential pitfalls of autonomy in this context (Matthews et al. Citation2018) and has underscored the heightened risk of burnout among salespeople due to the substantial stress they endure (McFarland and Dixon Citation2021). Many of these findings align with the outcomes of this study. Increased role ambiguity and the resulting frustration stemming from the lack of clear institutionalization of SI into NPD can serve as triggers for employee burnout. Potential conflicts arising from unfulfilled customer requests or internal prioritization of requests can engender negative emotions that may have long-term effects on salespeople. In this regard, it is also important to understand how SI into NPD may affect the revenue performance of a salesperson – both in the short run owing to reduced time for making sales with one’s customers or in the medium and long run owing to psychological overload and burnout whilst considering the potential upsides of SI into NPD.

Additionally, it seems worthwhile to explore SI into NPD also from the customer perspective, for example through a qualitative study to unravel their positive and negative experiences. This can add both robustness as well as further nuance to the framework proposed, particularly in terms of outcomes. For example, misaligned SI into NPD practices may be considered as overly aggressive selling approaches and the continuous rejection of requests may make customers more likely to switch. Similarly, SI into NPD may make the customer relationship more collaborative and interactive, hereby potentially strengthening it. These effects may also differ when interactions take place exclusively within e-commerce presences (e.g. Schwehm, Prigge, and Schwehm Citation2023). Lastly, this investigation started with SI into NPD. Exploring the setting in which SI into NPD is nested in (i.e. the organization as a whole), for example with regard to market and customer orientation, control mechanisms, and leadership styles, can further add to our understanding of the topic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, Stacy J. 1965. “Inequity in Social Exchange.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 2: 267–99. New York: Academic Press.

- Ahearne, Michael, Son K. Lam, Babak Hayati, and Florian Kraus. 2013. “Intrafunctional Competitive Intelligence and Sales Performance: A Social Network Perspective.” Journal of Marketing 77 (5): 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0217.

- Ahearne, Michael, John Mathieu, and Adam Rapp. 2005. “To Empower or Not to Empower Your Sales Force? An Empirical Examination of the Influence of Leadership Empowerment Behavior on Customer Satisfaction and Performance.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (5): 945–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.945.

- Allen, David G., Phillip C. Bryant, and James M. Vardaman. 2010. “Retaining Talent: Replacing Misconceptions with Evidence-Based Strategies.” Academy of Management Perspectives 24 (2): 48–64. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.24.2.48.

- Annunen, Petteri, Erno Mustonen, Janne Harkonen, and Harri Haapasalo. 2021. “Sales Capability Creation during New Product Development–Early Involvement of Sales.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 36 (13): 263–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-06-2020-0274.

- Arnett, Dennis B., Michael C. Wittmann, and John D. Hansen. 2021. “A Process Model of Tacit Knowledge Transfer between Sales and Marketing.” Industrial Marketing Management 93: 259–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.01.012.

- Arnett, Dennis B., and Michael C. Wittmann. 2014. “Improving Marketing Success: The Role of Tacit Knowledge Exchange between Sales and Marketing.” Journal of Business Research 67 (3): 324–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.01.018.

- Arnold, Todd J., Timothy D. Landry, Lisa K. Scheer, and Simona Stan. 2009. “The Role of Equity and Work Environment in the Formation of Salesperson Distributive Fairness Judgments.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 29 (1): 61–80. https://doi.org/10.2753/PSS0885-3134290104.

- Ashforth, Blake E., and Fred Mael. 1989. “Social Identity Theory and the Organization.” Academy of Management Review 14 (1): 20–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4278999.

- Bakan, Ismail, Yuliani Suseno, Ashly Pinnington, and Arthur Money. 2004. “The Influence of Financial Participation and Participation in Decision-Making on Employee Job Attitudes.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 15 (3): 587–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2004.10057654.

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. “The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 22 (3): 309–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115.

- Bande, Belén, Pilar Fernández-Ferrín, José A. Varela, and Fernando Jaramillo. 2015. “Emotions and Salesperson Propensity to Leave: The Effects of Emotional Intelligence and Resilience.” Industrial Marketing Management 44: 142–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.10.011.

- Barsky, Adam, Carl J. Thoresen, Christopher R. Warren, and Seth A. Kaplan. 2004. “Modeling Negative Affectivity and Job Stress: A Contingency-Based Approach.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 25 (8): 915–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.285.

- Boles, James S., George W. Dudley, Vincent Onyemah, Dominique Rouziès, and William A. Weeks. 2012. “Sales Force Turnover and Retention: A Research Agenda.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 32 (1): 131–40. https://doi.org/10.2753/PSS0885-3134320111.

- Boles, James S., Mark, W. Johnston, and Joseph F. Hair. Jr. 1997. “Role Stress, Work–Family Conflict and Emotional Exhaustion: Inter-Relationships and Effects on Some Work-Related Consequences.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 17 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.1997.10754079.

- Brashear, Thomas G., Chris Manolis, and Charles M. Brooks. 2005. “The Effects of Control, Trust, and Justice on Salesperson Turnover.” Journal of Business Research 58 (3): 241–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00134-6.

- Brashear, Thomas G., James S. Boles, Danny N. Bellenger, and Charles M. Brooks. 2003. “An Empirical Test of Trust-Building Processes and Outcomes in Sales Manager-Salesperson Relationships.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 31 (2): 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070302250902.

- Brockman, Beverly K., Melissa E. Rawlston, Michael A. Jones, and Diane Halstead. 2010. “An Exploratory Model of Interpersonal Cohesiveness in New Product Development Teams.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 27 (2): 201–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00710.

- Brown, Steven P., Evans, Kenneth R., Murali K. Mantrala, and G. Goutam Challagalla. 2005. “Adapting Motivation, Control, and Compensation Research to a New Environment.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 25 (2): 155–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2005.10749056.