Abstract

In recent years, some within chaplaincy have advocated for a stronger focus on outcomes, including outcome research, whereas others in the field have questioned an outcome-oriented perspective. In this article, existing outcome studies are reviewed in relation to the ongoing discussion about a process- or outcome-oriented approach to chaplaincy. A central question emerges from this discussion: how can outcome research be designed that respects the integrity of the profession of chaplaincy? A literature search in MEDLINE/Pubmed produced twenty-two chaplaincy outcome studies that met the inclusion criteria. A review of these studies shows that thus far most have focused on secondary chaplaincy outcomes (e.g., satisfaction) using quantitative designs. To respect the integrity of chaplaincy, it is recommended that future studies should also focus on characteristic chaplaincy outcomes, use mixed methods designs, and articulate more clearly how their chosen outcomes, outcome measures, and interventions relate to the work of chaplaincy.

Introduction

Recent years have seen the growth of research in the profession of chaplaincy. Specifically, the importance of research into the outcomes of chaplaincy care has been emphasized by some chaplaincy leaders and practicing chaplains. O'Connor and Meakes (Citation1998) and Peery (2012), for example, argue that outcome research is important for quality development within the profession because chaplains need to know if the care they deliver results in the outcomes they hope to achieve. From another perspective, Handzo, Cobb, Holmes, Kelly, and Sinclair (Citation2014) argue for outcome research because, in the context of modern evidence-based healthcare, the “funding of interventions and care providers is increasingly evaluated against the data for the efficacy of the intervention” (p. 43). They emphasize that chaplains are not exempt from this imperative and are required to prove their added value through outcome research. In Europe, the European Network of Health Care Chaplaincy issued the Salzburg Statement, calling for high quality research into healthcare chaplaincy outcomes in order to provide best spiritual care (Citation2014). In a secularized country such as The Netherlands, the Dutch Association of Spiritual Caregivers prioritizes outcome research to expand the legitimacy and basis for funding of the profession (Vereniging voor Geestelijk VerZorgers, Citation2014, p. 8). Finally, in two studies in the United States and the Netherlands, chaplains describe outcome research as a top research priority for the coming years (Damen, Delaney, & Fitchett, Citation2018; Damen, Schuhmann, Lensvelt-Mulders, & Leget, Citation2019).

Yet, outcomes and chaplaincy care are not obvious partners. Historically, the profession has valued personal competence, presence, and relationship building (inspired by, e.g., Sigmund Freud, William James, Carl Rogers and, in the Netherlands, Andries Baart) over methods and outcomes (Gleason, Citation1998; Kruizinga, Citation2017). From this perspective, chaplaincy is often characterized as process- rather than outcome-oriented, and chaplains are mostly familiar with thinking about process instead of outcome (Cadge, Calle & Dillinger, Citation2011; Lyndes et al., Citation2012). This began to change at the turn of the 21st century, when some chaplains started advocating for a stronger focus on outcomes (e.g., see VandeCreek & Lucas, Citation2001; Vandenhoeck, Citation2007 ). Following Gleason (Citation1998), Peery refers to a paradigm shift within chaplaincy, calling outcome-oriented chaplaincy the “operant paradigm for professional chaplaincy in the twenty-first century” (2012, p. 346). Some chaplains support this shift, as the recent calls within the literature demonstrate. Others, more cautious, suggest a critical approach toward outcomes (Jorna, Citation2005; Nolan, Citation2013, Citation2015), pointing out that “the question for chaplains is whether adapting to the new reality will be at the cost of distorting what we value and believe to be important about spiritual care” (Nolan, Citation2015, p. 94).

This article will discuss the role of outcome research in chaplaincy. Our central question is: How can outcome research be designed that respects the integrity of the profession of chaplaincy? To answer this question, we first start with a review of existing chaplaincy outcome studies in order to not only discuss the question theoretically but also look at empirical examples. We restrict ourselves to quantitative and mixed methods outcome studies. These studies are closer to the peak of the evidence-based pyramid (the level of cohort studies and higher), using the types of evidence considered to be the most reliable in the healthcare research paradigm (Straus, Glasziou, Richardson, & Haynes, Citation2019).

Second, to get insight into how these studies relate to chaplaincy values, we discuss the arguments about process- or outcome-oriented chaplaincy that influence chaplains' outlook on outcome research. Third, based on the arguments for or against outcomes in chaplaincy, we identify four questions that arise when designing chaplaincy outcome research and then critically discuss how to address these questions in order to respect the integrity of the profession. Finally, we turn back to the existing studies to examine how they deal with these questions and what we can learn for future outcome research. In the conclusion, we answer our central question.

Review of outcome studies: Method and results

Method

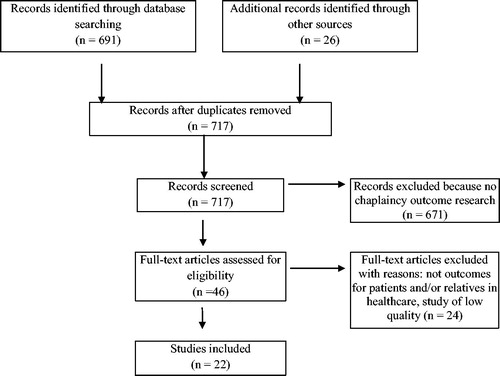

Eligible studies were identified by searching the MEDLINE/PubMed database following the PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, and PRISMA Group, Citation2009). The final search was run on April 24, 2018 with the following keywords: (Chaplain* OR pastor* OR “spiritual care*”) AND (outcome* OR effect*). No restrictions were made regarding the publication date. To supplement the search, review articles of chaplaincy research were scanned for relevant studies (Fitchett, Citation2017; Galek, Flannelly, Jankowski, & Handzo, Citation2011; Jankowski, Handzo, & Flannelly, Citation2011; Kalish, Citation2012; Lichter, Citation2013; Morgan, Citation2015; Mowat, Citation2008; Pesut, Sinclair, Fitchett, Greig, & Koss, Citation2016; Proserpio, Piccinelli, & Clerici, Citation2011; Steinhauser et al., Citation2017). Included articles were (a) peer-reviewed, (b) published in English, and (c) discussed outcomes for patients and/or relatives in healthcare. The flow chart of the search is presented in .

Results

Twenty-two articles reporting chaplaincy outcome research were identified. The articles are presented in . When we look at the chosen outcomes for the studies, we see that satisfaction with (chaplain) care is the outcome that is used most frequently. Other frequent outcomes include quality of life, anxiety, depression, religious coping, and spiritual well-being. Most studies focus on patient-reported outcomes from a wide variety of validated questionnaires; only four studies focus on other types of outcomes, such as care received at the end of life, medical costs, length of stay, and care visits (Balboni et al., Citation2010; Citation2011; Iler, Obenshain, & Camac, Citation2001; Rabow, Dibble, Pantilat, & McPhee, Citation2004). Many of the studies examine the impact of chaplain care by itself. Several of the studies examine the effects of chaplain care as a component of a multi-disciplinary intervention (Balboni et al., Citation2007, Citation2010, Citation2011; Daaleman, Williams, Hamilton, & Zimmerman, Citation2008; Rabow et al., Citation2004; Rummans et al., Citation2006; Sun et al., Citation2016; Williams, Meltzer, Arora, Chung, & Curlin, Citation2011). Most studies have a quantitative design; three studies add a qualitative component, resulting in mixed methods designs (Berning et al., Citation2016; Daaleman et al., Citation2008; Steinhauser et al., Citation2016).

Table 1. Outcome studies.

When we look at the findings, nine studies find a higher satisfaction with hospital or overall care of patients and relatives who were visited by a chaplain (Daaleman et al., Citation2008; Donohue et al., Citation2017; Iler et al., Citation2001; Johnson et al., Citation2014; Marin et al., Citation2015; Sharma et al., Citation2016; Vandecreek, Citation2004; Wall et al., Citation2007; Williams et al., Citation2011). Three studies find a high satisfaction with chaplain care (Purvis, Crowe, Wright, & Teague, Citation2018; Vandecreek, Citation2004; Wall et al., Citation2007). Four studies find a positive relationship between chaplaincy care and better patient quality of life (Balboni et al., Citation2007, Citation2010; Piderman et al., Citation2017; Rummans et al., Citation2006) and four studies show an increase in spiritual well-being (Kestenbaum et al., Citation2017; Piderman et al., Citation2017; Rabow et al., Citation2004; Sun et al., Citation2016). Three studies document a decrease in anxiety by patients visited by a chaplain (Berning et al., Citation2016; Iler et al., Citation2001; Rabow et al., Citation2004). Two studies find an increase in positive religious coping (Bay, Beckman, Trippi, Gunderman, & Terry, Citation2008; Piderman et al., Citation2017). One study finds a decrease in medical costs at the end of life (Balboni et al., Citation2011); one study a shorter length of stay (Iler et al., Citation2001); one study better mental well-being (Kevern & Hill, Citation2015); and one study a decrease in dyspnea, primary and urgent care visits, and an increase in sleep quality (Rabow et al., Citation2004).

It is clear from the articles that the studies are first attempts to research outcomes of chaplaincy care. Most study samples are relatively small; it is often unclear what the chaplain did that brought about the effect, and, in the case of the multidisciplinary interventions, whether the effect could be attributed to the chaplain’s intervention. The results should therefore be understood as initial indications of outcomes of chaplaincy care.

Outcomes and process in chaplaincy: Incompatible views or two sides of a coin?

The studies previously discussed are viewed with skepticism by some within chaplaincy. Understanding these concerns about outcome research will give insight into how research can be designed that respects the integrity of chaplaincy. We therefore continue with a critical analysis of the central arguments put forward in the discussion about chaplaincy as a process- or outcome-oriented profession.

A first key issue presented by chaplains critical of adopting an outcome-oriented approach is the characterization of chaplain activity as “presence.” Nolan writes:

For some, the idea that chaplains are “just there” encapsulates the essence of chaplaincy. Being “just there” means chaplains are those healthcare professionals who have time for people; those who humanize a healthcare system that is driven by the adrenaline of managerialist expediency and the testosterone of medical technology (2015, p. 95).

Being there is understood as forging a caring relationship with the other without the confinement of protocols, a focus on problem-solving, or any predetermined agenda (Baart, Citation2002; Madison, Citation1998). Elements within the intervention of presence emphasize being instead of doing, person-centeredness (leaving the agenda in the hands of those being served), and formation of a healing relationship as a means of providing effective spiritual care (Baart, Citation2002; Bouwer, Citation2003; Handzo et al., Citation2014; Jorna, Citation2005; Madison, Citation1998; Nolan, Citation2015). In summary, a central objection to adopting an outcome-oriented approach is that the focus on relationship will shift toward a focus on identifying and solving problems to attain a desired outcome (Baart, Citation2002; Bouwer, Citation2003; Jorna, Citation2005; Nolan, Citation2015).

Outcome-oriented chaplaincy, rooted in the work of Lucas and colleagues, comprises a cyclical model based on assessing another's needs, hopes, and resources; determining appropriate interventions; and measuring outcomes (Lucas, Citation2001). Chaplains also refer to this model as the diagnostic or medical model. Those who object to this model say that it places the patient in a pathological schema in which something needs to be fixed. It invites stigmatization and dehumanization of the patient because the patient is perceived as an object instead of a subject (Bouwer, Citation2003; Nolan, Citation2015). Moreover, the model encourages standardization, a development that runs counter to the centrality of the relationship in chaplaincy practice, in which it matters who performs the intervention and in which the unique other in his/her context is the focus of the chaplain’s attention. This especially holds true for outcome research, in which standardization is required for the predictability and replicability of the results (Nolan, Citation2015). Standardization could furthermore mitigate variance in practice, restrict professional decision-making, and reduce whole person care by employing predefined interventions for localized needs (Nolan, Citation2015). Finally, it has been observed that some chaplains fear the model instrumentalizes the spiritual that actually transcends us (humanity) (see Gleason, Citation1998, p. 10; Smit, Citation2015).

Chaplains who advocate for an outcome-oriented approach counter that all chaplains, including process-oriented chaplains, carry out assessments and perform specific interventions directed at outcomes because they interpret the other's situation (diagnose) and use this information in their response (intervene) to cultivate a relationship (effect outcome) (Bouwer, Citation2003). They argue that in focusing solely on process, chaplains may not sufficiently attend to their interpretations, responses, and outcomes, forgoing the conscious reflection that increases accountability (Bos, Citation2003; Bouwer, Citation2003; Peery, Citation2012).

Furthermore, pitfalls of the outcome-oriented model can be avoided by developing narrative assessments that provide space for unique individual context and a transcendent reality; such assessments can be carried out in dialog with the patient (Bos, Citation2003; Bouwer, Citation2003). Mackor (Citation2007) proposes to stop talking about standardization in general and start differentiating between various standards. The outcome-oriented model should also not be understood as a goal in itself but as a means to better understand the patient (Bos, Citation2003). A final advantage is that speaking about assessments, interventions, and outcomes aligns with the language spoken in healthcare and therefore promotes integration of chaplaincy into the healthcare system, demonstrating chaplains’ added value to clinical colleagues (Bouwer, Citation2003; Handzo et al., Citation2014; Lucas, Citation2001; Peery, Citation2012). The emphasis on evidence-based chaplaincy (Fitchett, White, & Lyndes, Citation2018) may create related concerns for some chaplains. Frequently, these concerns are based on a misunderstanding of evidence-based practice that includes care informed by the best available research but uses clinical judgment to apply that care in light of patient/client unique values (APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice, Citation2006).

In order to arrive at a nuanced understanding of what it means to respect the integrity of chaplaincy in outcome research, it seems important to take the discussion a step further beyond either-or positions. Models can be found for this in the domain of psychotherapy—where a similar discussion around outcomes is taking place—that support the idea that the focus on process and the focus on outcome “should not really be considered as separate, but rather as two sides of a coin” (Ardito & Rabellino, Citation2011, p. 2). An understanding of the connection between processes and outcomes in chaplaincy can be advanced by the view that chaplaincy practice—like other professions—is directed toward and guided by an aspiration to certain “visions of the good” (MacIntyre, Citation2007; Schumann & Damen, Citation2018; Sennett, Citation2009; Taylor, Citation1989). MacIntyre (Citation2007) argues: “every activity, every enquiry, every practice aims at some good” (p. 173).

Likewise, chaplains aim at effecting some change for the better in their practice. Within chaplaincy, goods are the ends that, however implicit, chaplains strive towards, and these goods constitute what they see as changes for the better. We may understand outcomes in terms of these goods. Chaplaincy practices have a good outcome when they contribute to chaplaincy goods and a bad outcome when they do not. As a result, outcomes, informed by visions of the good inherent in chaplaincy, necessarily resonate in chaplaincy practices.

In this view, processes and outcomes are intrinsically connected in chaplaincy; processes are directed toward outcomes and outcomes guide processes. This also applies to a process-oriented approach to chaplaincy. We might say that chaplains who use a process-oriented approach work with an “agenda” consisting of visions of the good to which they hope to contribute. This is not the same as having an agenda of what they wish to achieve in a particular encounter. Thinking about the outcomes of chaplaincy is then related to the question of what are visions of the goods that guide chaplaincy practices.

In order to evaluate the contribution that chaplains make to chaplaincy goods in certain situations, we need to translate the concept of chaplaincy goods into concrete standards applicable to actual practices. This is where outcome research is important. It involves systematically thinking about the question of how to translate visions of the good into manageable outcomes that allow for empirical exploration. In the case of chaplaincy this is obviously not a straightforward question, bearing in mind the issues raised in the discussion about process- and outcome-oriented chaplaincy. Furthermore, chaplaincy goods involve concepts like spirituality and transcendence, which are notoriously difficult to define, let alone explore empirically. Finally, there is minimal consensus within the profession about what are essential chaplaincy goods and relevant chaplaincy outcomes (Handzo et al., Citation2014). None of these are reasons to give up on outcome research into chaplaincy. These uncertainties do, however, necessitate that researchers be precise, thoughtful, and transparent in their choices when translating chaplaincy goods into outcomes that can be measured empirically. To clarify these requirements for precision, thoughtfulness, and transparency in outcome research, in the next section we take a closer look at several of the choices that researchers face when designing outcome research in chaplaincy.

Designing outcome studies in chaplaincy: Four questions

Based on the arguments in the discussion regarding process- or outcome-oriented chaplaincy, we have identified four questions that come up when translating chaplaincy goods into a specific study design: (a) What is the audience and context of our study? (b) What outcomes do we choose? (c) How do we assess these outcomes? (d) Do we choose to study outcomes in the form of effects of standardized interventions? The answer to (a) will influence the answers to the other three questions.

What is the audience and context of our study?

The first question we need to answer when designing a chaplaincy outcome study concerns the audience of our study: whom do we address with our study? In doing empirical chaplaincy research, we give an account of chaplaincy practices. Giving an account involves addressing an audience, the people to whom we give the account. This audience may just consist of oneself when the motive for doing research is the desire to answer the question: do I deliver good care as a chaplain? When we publish our research, however, we have a larger audience than just ourselves in mind. In chaplaincy research, an obvious audience that we may address is other chaplains. If we also have a strategic objective, then we need to ask ourselves whom we want to convince of the value of healthcare chaplaincy through this research and what this implies for choices in designing an outcome study.

The choice of the study audience indicates the inevitable political aspect of outcome research: the choices we make when designing an outcome study have a bearing on its status as evidence of the value of chaplaincy. In designing outcome research, we cannot avoid issues of power: who has power in deciding what counts as good healthcare, as appropriate outcomes, and as convincing research. For instance, at present, research in healthcare follows the paradigm of evidence-based medicine, valuing quantitative research in the form of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses as the highest levels of evidence (The Council for Public Health and Society, Citation2017). This research follows a positivist natural science paradigm. Researchers get to know reality by deducing general laws from empirical observations in standardized experiments. With its emphasis on individual processes of meaning-making, chaplaincy has a strong connection with the constructivist paradigm, according to which facts cannot be separated from interpretation and meaning making (Gergen, Citation2001).

The previous section showed that, in line with this difference in paradigms, research following the positivist paradigm is often seen as incompatible with chaplaincy values. Taking the political aspect of outcome research into account, however, it may be advisable—to be accepted in certain contexts—to follow the dominant paradigm in healthcare outcome research when designing outcome studies in chaplaincy (Leget, Citation2017).

Yet, more generally, we may argue that to respect the integrity of chaplaincy we need different narratives regarding the value of chaplaincy, not only in order to have this value recognized by different audiences, but also in order to enrich our accounts of chaplaincy. Carl Rogers (Citation1963) distinguishes three types of knowing, all of which are required for the scientific understanding of practice: objective knowing, involving the measurement of operationalized constructs; subjective knowing; and interpersonal knowing (Balkin, Citation2014). In this view, different forms of research add to a better understanding of chaplaincy practice.

What outcomes do we choose?

The second choice we need to make when designing an outcome study in healthcare chaplaincy concerns the outcome itself. Do we want to study characteristic chaplaincy outcomes that represent intrinsic chaplaincy goods, or do we want to study secondary outcomes of chaplaincy care (e.g., clinical or physiological outcomes)?

With regard to the first choice, we have already pointed out that there seems to be no shared understanding among chaplains of what constitute characteristic chaplaincy outcomes. With regard to the second option, when we want to prove the value of chaplaincy in healthcare, restricting ourselves to characteristic chaplaincy outcomes may limit the evidential power of our studies. Still, secondary outcomes of chaplaincy are often regarded with suspicion by chaplains, in particular when these involve hard outcome measures such as cost reduction: “The particular outcomes the system now values, especially cost reduction, are also considered by many chaplains as antithetical to how the profession has seen itself, because they violate what chaplains perceive as their focus on the human spirit as opposed to any alignment with health care being perceived as business-related” (Handzo et al., Citation2014, p. 46).

It might be helpful to notice that an outcome represents a normative understanding of what is seen as important and desirable in a certain context. In particular, outcomes that are generally understood to be relevant healthcare outcomes represent specific understandings of what is considered good in healthcare. For instance, clinical outcomes represent the value that good healthcare cures people; the outcome of cost reduction represents the value that in good healthcare, resources are used efficiently.

Consequently, the question that needs to be addressed with respect to the choice of outcome is: how does the understanding of good healthcare represented by a chosen outcome relate to chaplains’ visions of good healthcare? Addressing this question may prevent us from evaluating chaplaincy using values and visions that are not consistent with chaplaincy’s own values and visions. However, it may also prevent us from too easily writing off outcomes of cost reduction or efficiency as purely “business-related” and therefore antithetical to chaplaincy values. For example, efficient use of resources may also be understood from the perspective of justice: efficiency provides good care to as many people as possible. Therefore, at the level of choosing an outcome, respecting the integrity of chaplaincy requires that we explicate the connection between the chosen outcome and chaplains’ visions of good healthcare.

How do we assess these outcomes?

Given a certain choice of outcome, the next choice we face when designing an outcome study in healthcare chaplaincy is how to assess the outcome. Assessments of outcomes are attempts to capture change that has taken place during a process. What we consider an appropriate method to assess outcomes depends on our (explicit or implicit) understanding of change. For instance, when the focus is on easily observable changes (e.g., behavioral change or symptom reduction), it is more obvious that such change might be measured quantitatively than when we focus on complex changes in, for example, experience, relationships, or meaning making.

Chaplains generally consider themselves to be dealing with extremely complex and idiosyncratic change processes, the richness and depth of which is easily lost, especially when assessed quantitatively with standardized outcome measures. However, outcome studies into chaplaincy do not necessarily need to capture the whole complexity of change that occurs in chaplaincy processes. To respect the integrity of the profession does require an explication of the kind of change we are attempting to capture and our considerations regarding the choice of particular methods and instruments.

Do we choose to establish outcomes in the form of effects of standardized interventions?

As highlighted earlier, a main objection to outcome research is that it requires standardization to make outcomes replicable and predictable (Nolan, Citation2015). According to this view, standardization runs counter to important chaplaincy values. The rejection of standardized interventions can leave chaplain researchers with no description of the substance of their intervention. In this situation some have said the substance of the chaplains’ intervention is “a black box” whose contents cannot be observed. While this type of research informs us about the effect of a visit by a chaplain, it does not clarify what brought about the effect. In light of our previous argument about the importance of various research types for creating a rich account of the value of chaplaincy, simply ruling out research that looks for replicable and predictable outcomes seems too hasty a conclusion.

Another possibility is to look at chaplaincy practice as consisting of several elements, some of which are appropriate for standardized research and others that are not. This requires recognition that any standardized intervention does not represent the whole of chaplaincy practice. Therefore, in respecting the integrity of chaplaincy, it is important that we explicate how the standardized intervention that we choose to research is related to chaplaincy practices more generally.

RCTs probably constitute the most obvious type of standardized outcome research. The use of RCTs is a subject of discussion not only in chaplaincy, but also in other types of counseling where the issue is whether or not the use of RCTs is at odds with a focus on the individual person and the uniqueness of each encounter. Scholl, Ray, and Brady-Amoon (Citation2014) argue that RCTs (and, more generally, quantitative methods in outcome research) should not be written off as inevitably dehumanizing. They describe several possibilities for designing RCTs such that they do not conflict with respect for the individual person. For example, a standardized intervention might include work with the (individual) life story. They also discuss the limitations of a restriction to qualitative methods alone and advocate the use of mixed methods as the approach to research that is “the most thorough approach to research and is also the most theoretically aligned with humanistic principles” (Scholl, Ray, & Brady-Amoon, Citation2014, p. 233). Following these ideas, when we decide to use standardized interventions in our chaplaincy study, we may, for instance, consider how additional qualitative research might add to an understanding of the relation between intervention and outcome in descriptive terms in addition to analysis of quantitative data. If possible, we could include this in our design.

Reviewing existing outcome studies: Audiences, outcomes, outcome measures, and interventions

We will now turn back to the existing chaplaincy outcome studies to take a closer look at the choices that were explicitly or implicitly made in relation to the four questions just discussed. With respect to the first question—what is the audience and context of the study—we see that the studies address roughly two different audiences: clinicians and chaplains. Approximately three-quarters of the studies were published in medical journals and one-quarter in journals on chaplaincy or religion. There is little variation in study designs; the vast majority of the studies have a quantitative research design regardless of audience. Only three studies add qualitative methods, resulting in mixed methods designs (Berning et al., Citation2016; Daaleman et al., Citation2008; Steinhauser et al., Citation2016). We argued that for respecting the integrity of chaplaincy we need different narratives from different forms of research for a good understanding of chaplaincy practices. Following from the existing studies, extra attention could be paid to mixed methods designs.

Applying the second question—what outcomes do we choose—we saw before that the outcome of satisfaction with (chaplain) care was chosen most frequently. Other outcomes included quality of life, anxiety, depression, spiritual well-being, and religious coping. When we look at the chosen outcomes specifically in relation to characteristic chaplaincy goods, the majority do not appear to be outcomes exclusive to chaplaincy; many could also be considered relevant to the work of other healthcare professionals. For example, focusing on patient experience (satisfaction) or well-being is crucial in good healthcare. It is by no means incompatible with chaplaincy values but also not unique to the profession.

The outcomes that seem specific to chaplaincy, for example, spiritual well-being, religious coping, and hope, have been studied less frequently. We argued that respecting the integrity of chaplaincy in choosing an outcome requires that we explicate the connection between the chosen outcome and chaplains’ visions of good healthcare. This explanation is missing in most studies. Only a few studies give a brief description in broad terms, explaining, for example, that chaplains attend to spiritual/religious needs and psycho-emotional distress and, therefore, spiritual/religious and psycho-emotional measures are a suitable choice.

Answering the third question—how do we assess these outcomes—we see that the chosen outcomes were predominantly assessed quantitatively, using a wide variety of patient-reported questionnaires. We argued that in choosing a method to assess an outcome, respecting the integrity of chaplaincy requires explicating both what kind of change we attempt to capture and our rationale for selecting particular methods and instruments. The most frequently researched outcome, satisfaction, is an outcome that can only be assessed in hindsight and therefore does not necessarily give us information about what kind of change is associated with chaplain care.

The other outcomes in the studies referred to more complex concepts like quality of life, anxiety, or depression. Change for these outcomes was assessed with questionnaires developed in contexts broader than chaplaincy. In the studies that focus on apparent characteristic chaplaincy outcomes such as spiritual well-being, religious coping, and hope, the most often used questionnaires are the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual (FACIT-SP) and the Brief Religious Coping Scale (Brief RCOPE), followed by the Religious Problem Solving Scale, the McBride Spirituality Assessment, Steinhauser's “Are you at peace?,” the Spiritual Well-being Scale and the Herth Hope Index. It is outside of the scope of this article to discuss if those questionnaires are valid measures for chaplaincy outcomes; it would be interesting for further exploration. None of the studies explicate their rationale for using these measures in relation to chaplaincy goods. Note that there is a questionnaire specifically developed for chaplaincy: the Patient Reported Outcome Measure (PROM) by Snowden and Telfer (Citation2017). We are looking forward to further results from this questionnaire.

When we review the final question—do we choose to establish outcomes in the form of effects of standardized interventions—we see that most studies worked with a “black box” design. These studies focus on chaplaincy care as usual, without examining specific predefined interventions. It therefore remains unclear which actions of the chaplain brought about a certain effect, a problem compounded in studies in which chaplains contribute to multidisciplinary interventions.

Some studies chose to document the activities of the chaplain (Johnson et al., Citation2014; Sharma et al., Citation2016), giving some information about what could have brought about the effect. Several studies examined a predefined structured intervention, in which it was clear what the chaplain was going to do, despite strong resistance within the field to standardizing interventions. Interestingly, however, the studied interventions;Spiritual AIM (Kestenbaum et al., Citation2017), Hear My Voice (Piderman et al., Citation2017) and the Caregiver Outlook (Steinhauser et al., Citation2016)—offered a framework or semistructured protocol while also keeping the content of conversation highly individualized, since the interventions are intended to enable clients to relate personal stories. We argued that respecting the integrity of chaplaincy requires explicating how the standardized intervention is related to chaplaincy practice more generally. All three studies clearly explicate how the interventions relate to chaplaincy practice, pointing out that the interventions are embedded in the profession's focus on meaning-making, life review, relational well-being, and sense of loss and hope.

Conclusion

In this article we first explored the question: how can outcome research be designed that respects the integrity of the profession of chaplaincy? We started with a literature search of outcome studies to situate these studies in the ongoing discussion about process- or outcome-oriented chaplaincy. Twenty-two articles reporting chaplaincy outcomes were identified that met inclusion criteria.

Second, we reviewed the discussion about chaplaincy as a process- or outcome-oriented profession to get a better understanding of the resistance to outcome research. We stated that chaplaincy practice is ultimately guided by certain visions of the good that can also be understood as outcomes of chaplaincy. We concluded that chaplaincy is necessarily outcome-oriented because it is aimed at supporting some change for the better towards these goods. Hence, processes and outcomes are connected; processes are directed toward outcomes and outcomes guide processes.

Third, we developed four questions from our understanding of the resistance to outcome research, questions that are relevant when relating chaplaincy outcomes to a specific study design: (a) what is the audience and context of the study? (b) what outcomes do we choose? (c) how do we assess these outcomes? (d) do we choose to establish outcomes in the form of effects of standardized interventions? We concluded that respecting the integrity of chaplaincy in study design means: first, we need various narratives in order to get a rich account of the value of chaplaincy that can be recognized by different audiences. Quantitative as well as qualitative types of research can provide this evidence. Second, when choosing an outcome for our study, we have to explicate the connection between the chosen outcome and chaplains’ visions of good healthcare. Third, we need to specify what kind of change we attempt to demonstrate in our study and explain our rationale for using particular methods and instruments. Finally, because no standardized intervention represents the whole of chaplaincy practice, we need to explicate how the researched intervention is related to chaplaincy practice more generally.

We then reviewed existing outcome studies with the help of these considerations. We found that the studies were aimed at two different audiences. Most studies were quantitative, but some added qualitative methods, resulting in mixed methods designs. Only a few of the outcomes studied could be described as outcomes unique to chaplaincy, for example, spiritual well-being, religious coping, and hope. Other outcomes used, such as satisfaction with care, quality of life, anxiety, and depression are also relevant for other professions. The outcome measures used were developed and validated for broader contexts than just chaplaincy. Most studies did not explicate how their outcomes and outcome measures related to chaplaincy practices specifically. Most of the research was “black-box” research; that is, the studies examined chaplain care but remained unclear what the chaplain did that brought about the effect. A few studies focused on more standardized interventions which followed a protocol but invited a highly individualized response. These studies did explicate the relation between the standardized interventions and practices within chaplaincy.

To respect the integrity of chaplaincy, it is recommended that future outcome studies more often use mixed methods designs in order to give a broader account of the variance in chaplaincy practices and to continue reaching different audiences. Furthermore, future studies should focus more explicitly on characteristic chaplaincy outcomes than existing studies, which thus far mainly look at general outcomes of chaplaincy care. As this requires well-founded ideas about what are understood as distinctive features of chaplaincy, we want to point out the importance of having a thorough and continuing dialog among chaplains and chaplaincy researchers about what are characteristic chaplaincy goods and their related outcomes. Finally, more studies could be conducted that focus on opening the “black box” of chaplaincy care. This is an area where the growing body of chaplain case studies may be helpful (Fitchett & Nolan, Citation2015, Citation2018).

Because of the brief history of chaplaincy research and the minimal resources available, most studies so far have been opportunistic in that chaplaincy researchers have taken advantage of available opportunities. We hope that with growing resources the time may be ripe for more intentionally developing chaplaincy outcome research. This would include explicating in research designs how the studied outcomes, outcome measures, and interventions relate to the chaplaincy profession.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the assistance of Marcia Nelson in preparing the manuscript for publication.

References

- APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Journal of Psychology, 61(4), 271.

- Ardito, R. B., & Rabellino, D. (2011). Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: Historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 270. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270

- Baart, A. (2002). The Presence Approach: an introductory sketch of practice. Retrieved from http://///C:/Users/Annelieke/Downloads/Presence_approach__introduction%20(1).pdf

- Balboni, T., Balboni, M., Paulk, M. E., Phelps, A., Wright, A., Peteet, J., … Prigerson, H. (2011). Support of cancer patients' spiritual needs and associations with medical care costs at the end of life. Cancer, 117(23), 5383–5391. doi:10.1002/cncr.26221

- Balboni, T. A., Paulk, M. E., Balboni, M. J., Phelps, A. C., Loggers, E. T., Wright, A. A., … Prigerson, H. G. (2010). Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: Associations with medical care and quality of life near death. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(3), 445. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005

- Balboni, T. A., Vanderwerker, L. C., Block, S. D., Paulk, M. E., Lathan, C. S., Peteet, J. R., & Prigerson, H. G. (2007). Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(5), 555. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046

- Balkin, R. S. (2014). Principles of quantitative research in counseling: A humanistic perspective. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 53(3), 240. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2014.00059.x

- Bay, P., Beckman, D., Trippi, J., Gunderman, R., & Terry, C. (2008). The effect of pastoral care services on anxiety, depression, hope, religious coping, and religious problem solving styles: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Religion and Health, 47(1), 57–69. doi:10.1007/s10943-007-9131-4

- Berning, J. N., Poor, A. D., Buckley, S. M., Patel, K. R., Lederer, D. J., Goldstein, N. E., … Baldwin, M. R. (2016). A novel picture guide to improve spiritual care and reduce anxiety in mechanically ventilated adults in the intensive care unit. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 13(8), 1333–1342. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201512-831OC

- Bos, T. (2003). Levensbeschouwlijke diagnostiek in de GGZ. Tijdschrift Geestelijke Verzorging, 6(28), 63–69.

- Bouwer, J. (2003). De hermeneutisch-diagnostische competentie van de geestelijk zorgverlener. Tijdschrift Geestelijke Verzorging, 6(28), 83–87.

- Cadge, W., Calle, K., & Dillinger, J. (2011). What do chaplains contribute to large academic hospitals? The perspectives of pediatric physicians and chaplains. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(2), 300–312. doi:10.1007/s10943-011-9474-8

- Daaleman, T. P., Williams, C. S., Hamilton, V. L., & Zimmerman, S. (2008). Spiritual care at the end of life in long-term care. Medical Care, 46(1), 85–91. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181468b5d

- Damen, A., Delaney, A., & Fitchett, G. (2018). Research priorities for healthcare chaplaincy: Views of U.S. Chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 24(2), 57–66. doi:10.1080/08854726.2017.1399597

- Damen, A., Schuhmann, C., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., & Leget, C. (2019). Research priorities for health care chaplaincy in The Netherlands - A Delphi study among Dutch chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy. doi:10.1080/08854726.2018.1473833

- Donohue, P. K., Norvell, M., Boss, R. D., Shepard, J., Frank, K., Patron, C., & Crowe, T. (2017). Hospital chaplains: Through the eyes of parents of hospitalized children. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20(12). doi:10.1089/jpm.2016.0547

- European Network of Health Care Chaplaincy. (2014). Salzburg Statement of the 13th consultation of the European Network of Health Care Chaplaincy. Retrieved from http://www.enhcc.eu/2014_salzburg_statement.pdf

- Fitchett, G. & Nolan, S. (2015). Spiritual care in practice: Case studies in healthcare chaplaincy. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Fitchett, G. & Nolan, S. (2018). Case studies in spiritual care. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Fitchett, G. (2017). Recent progress in chaplaincy-related research. Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling, 71(3), 163–175. doi:10.1177/1542305017724811

- Fitchett, G., White, K. B., & Lyndes, K. (2018). Evidence-based healthcare chaplaincy; A research reader. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Galek, K., Flannelly, K. J., Jankowski, K. R. B., & Handzo, G. (2011). A methodological analysis of chaplaincy research: 2000–2009. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 17(3–4), 126–145. doi:10.1080/08854726.2011.616167

- Gergen, K. J. (2001). Social construction in context. London, UK: Sage.

- Gleason, J. J. (1998). An emerging paradigm in professional chaplaincy. Chaplaincy Today, 14(2), 9–14. doi:10.1080/10999183.1998.10767090

- Handzo, G. F., Cobb, M., Holmes, C., Kelly, E., & Sinclair, S. (2014). Outcomes for professional health care chaplaincy: An international call to action. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 20(2), 43–53. doi:10.1080/08854726.2014.902713

- Iler, W. L., Obenshain, D., & Camac, M. (2001). The impact of daily visits from chaplains on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A pilot study. Chaplaincy Today, 17(1), 5–11. doi:10.1080/10999183.2001.10767153

- Jankowski, K. R. B., Handzo, G., & Flannelly, K. J. (2011). Testing the efficacy of chaplaincy care. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 17(3–4), 100–125. doi:10.1080/08854726.2011.616166

- Johnson, J. R., Engelberg, R. A., Nielsen, E. L., Kross, E. K., Smith, N. L., Hanada, J. C., … Curtis, J. R. (2014). The association of spiritual care providers’ activities with family members’ satisfaction with care after a death in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 42(9), 1991–2000. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000000412

- Jorna, T. (2005). De geestelijke dimensie in de geestelijke verzorging. Kritische Noties Bij Bouwers Competenties Van Het Vak. Tijdschrift Geestelijke Verzorging, 8(34), 36–46.

- Kalish, N. (2012). Evidence-based spiritual care: A literature review. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 6(2), 242–246. doi:10.1097/SPC.0b013e328353811c

- Kestenbaum, A., Shields, M., James, J., Hocker, W., Morgan, S., Karve, S., … Dunn, L. B. (2017). What impact do chaplains have? A pilot study of spiritual AIM for advanced cancer patients in outpatient palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(5), 707–714. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.027

- Kevern, P., & Hill, L. (2015). ‘Chaplains for well- being’ in primary care: Analysis of the results of a retrospective study. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 16(1), 87. doi:10.1017/S1463423613000492

- Kruizinga, R. (2017). Out of the blue. Experiences of contingency in advanced cancer patients. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: University of Amsterdam.

- Leget, C. (2017). Spiritual Care als toekomst van de geestelijke verzorging. Religie and Samenleving, 12(2/3), 96–106.

- Lichter, D. A. (2013). Studies show spiritual care linked to better health outcomes. Health Progress, 94(2), 62–66.

- Lucas, A. M. (2001). Introduction to the discipline for pastoral caregiving. In L. Vandecreek & A.M. Lucas (eds.), The discipline for pastoral care giving: Foundations for outcome orientated chaplaincy (pp. 1–33). New York, NY and London, UK: Routledge.

- Lyndes, K. A., Fitchett, G., Berlinger, N., Cadge, W., Misasi, J., & Flanagan, E. (2012). A survey of chaplains' roles in pediatric palliative care: Integral members of the team. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 18(1–2), 74–93. doi:10.1080/08854726.2012.667332

- MacIntyre, A. (2007). After virtue: A study in moral theory (3rd ed.). London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Mackor, A. R. (2007). Standaardisering van geestelijke verzorging. Tijdschrift Geestelijke Verzorging, 10(44), 21–37.

- Madison, T. E. (1998). Can chaplaincy be sold without selling out? Chaplaincy Today, 14(2), 3–8. doi:10.1080/10999183.1998.10767089

- Marin, D. B., Sharma, V., Sosunov, E., Egorova, N., Goldstein, R., & Handzo, G. F. (2015). Relationship between chaplain visits and patient satisfaction. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 21(1), 14–24. doi:10.1080/08854726.2014.981417

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

- Morgan, M. (2015). Review of literature. Melbourne, Australia: Spiritual Health Victoria.

- Mowat, H. (2008). The potential for efficacy of healthcare chaplaincy and spiritual care provision in the NHS (UK): A scoping review of recent research. Aberdeen, Scotland: Mowat Research.

- Nolan, S. (2013). Re-evaluating chaplaincy: To Be, or Not…. Journal of Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 1(1), 49–60. doi:10.1558/hscc.v1i1.49

- Nolan, S. (2015). Health care chaplains responding to change: embracing outcomes of reaffirming relationships? Health and Social Care Chaplaincy, 3(2), 93–109. doi:10.1558/hscc.v3i2.27068

- O'Connor, T. S., & Meakes, E. (1998). Hope in the midst of challenge: Evidence-based pastoral care. Journal of Pastoral Care, 52(4), 359–367.

- Peery, B. (2012). Outcome oriented chaplaincy: Intentional caring. In S. Roberts (ed.), Professional spiritual and pastoral care: A practical clergy and chaplain’s handbook (pp. 342–361). Woodstock, VT: SkyLight Paths Publishing.

- Pesut, B., Sinclair, S., Fitchett, G., Greig, M., & Koss, S. (2016). Health care chaplaincy: A scoping review of the evidence 2009–2014. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 22(2), 67–84. doi:10.1080/08854726.2015.1133185

- Piderman, K. M., Radecki Breitkopf, C., Jenkins, S. M., Lapid, M. I., Kwete, G. M., Sytsma, T. T., … Jatoi, A. (2017). The impact of a spiritual legacy intervention in patients with brain cancers and other neurologic illnesses and their support persons. Psycho‐oncology, 26(3), 346–353. doi:10.1002/pon.4031

- Proserpio, T., Piccinelli, C., & Clerici, C. (2011). Pastoral care in hospitals: A literature review. Tumori, 97(5), 666–671. doi:10.1700/989.10729

- Purvis, T., Crowe, T., Wright, S., & Teague, P. (2018). Patient appreciation of student chaplain visits during their hospitalization. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(1), 240–248. doi:10.1007/s10943-017-0530-x

- Rabow, M. W., Dibble, S. L., Pantilat, S. Z., & McPhee, S. J. (2004). The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164(1), 83–91. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.1.83

- Rogers, C. R. (1963). Toward a science of the person. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 3(2), 72–92. doi:10.1177/002216786300300208

- Rummans, T. A., Clark, M. M., Sloan, J. A., Frost, M. H., Bostwick, J. M., Atherton, P. J., … Hanson, J. (2006). Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(4), 635–642. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.209

- Scholl, M. B., Ray, D. C., & Brady-Amoon, P. (2014). Humanistic counseling process, outcomes, and research. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 53, 218–239. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2014.00058.x

- Schumann, C., & Damen, A. M. (2018). Representing the good: Pastoral care in a secular age. Pastoral Psychology, 67(4), 405–417. doi:10.1007/s11089-018-0826-0

- Sennett, R. (2009). The craftsman. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Sharma, V., Marin, D. B., Sosunov, E., Ozbay, F., Goldstein, R., & Handzo, G. F. (2016). The differential effects of chaplain interventions on patient satisfaction. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 22(3), 85–101. doi:10.1080/08854726.2015.1133203

- Smit, J. (2015). Antwoord geven op het leven zelf. Delft, Netherlands: Eburon.

- Snowden, A., & Telfer, I. (2017). Patient reported outcome measure of spiritual care as delivered by chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 23(4), 131–155. doi:10.1080/08854726.2017.1279935

- Steinhauser, K. E., Fitchett, G., Handzo, G. F., Johnson, K. S., Koenig, H. G., Pargament, K. I., … Balboni, T. A. (2017). State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research part I: Definitions, measurement, and outcomes. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(3), 428–440. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.028

- Steinhauser, K. E., Olsen, A., Johnson, K. S., Sanders, L. L., Olsen, M., Ammarell, N., & Grossoehme, D. (2016). The feasibility and acceptability of a chaplain-led intervention for caregivers of seriously ill patients: A caregiver outlook pilot study. Palliative and Supportive Care, 14(05), 456–467. doi:10.1017/S1478951515001248

- Straus, S. E., Glasziou, P., Richardson, W. S., & Haynes, B. (2019). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (5th ed.). Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier.

- Sun, V., Kim, J. Y., Irish, T. L., Borneman, T., Sidhu, R. K., Klein, L., & Ferrell, B. (2016). Palliative care and spiritual well-being in lung cancer patients and family caregivers. Psycho-oncology, 25(12), 1448–1455. doi:10.1002/pon.3987

- Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of the modern identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- The Council for Public Health and Society. (2017). No evidence without context. About the illusion of evidence‐based practice in healthcare. Retrieved from https://www.raadrvs.nl/en/item/no-evidence-without-context

- VandeCreek, L. (2004). How satisfied are patients with the ministry of chaplains? Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling , 58(4), 335–342. doi:10.1177/154230500405800406

- Vandecreek, L., & Lucas, A. M. (2001). The discipline for pastoral care giving: Foundations for outcome orientated chaplaincy. New York, NY and London, UK: Routledge.

- Vandenhoeck, A. (2007). De meertaligheid van de pastor in de gezondheidszorg. Leuven, Belgium: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

- Vereniging voor Geestelijk Verzorgers. (2014). Beleidsplan VGVZ 2014-2018. Retrieved from http://vgvz.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/MJB_VGVZ_2014-2018.pdf.

- Wall, J. R., Engelberg, A. R., Gries, J. C., Glavan, R., Bradford., & Curtis, R., J. (2007). Spiritual care of families in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 35(4), 1084–1090. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000259382.36414.06

- Williams, J., Meltzer, D., Arora, V., Chung, G., & Curlin, F. (2011). Attention to inpatients’ religious and spiritual concerns: Predictors and association with patient satisfaction. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(11), 1265–1271. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1781-y