ABSTRACT

Administrative data sets can play a key role in informing and influencing education provision. To date, longitudinal analysis of special educational needs (SEN) in Northern Ireland (NI) has not been a visible feature of policy discourse, even though the number of these pupils has increased at a rate that is proportionally higher than the general school population. To better understand the prevalence of SEN, this paper utilises secondary educational data collected between 2010/11 and 2021/22 to interrogate trends in NI as well as relative to other jurisdictions. Findings identify the intricacy of comparative analysis, not least due to differing approaches to data collection and reporting, as well as approaches to assessment and identification of SEN. More specifically, within the NI context, the findings identify fundamental trends across school types. The association between these trends and significant policy changes in how SEN is identified, recorded and reported is critically considered. The utility of big data is discussed, including implications for generating robust evidence, contributing to forward-planning on the future monitoring of, and provision for, SEN, and reinforcing the need for accessible new data to improve the visibility of SEN in the region.

Introduction

Pupils with special educational needsFootnote1 (SEN) represent a sizeable proportion of the total school population across the UUK, with up to 20% of children requiring some form of targeted support to meet their learning needs (DE Citation2019; DfE Citation2019b). In the Northern Ireland (NI) context, provision for SEN has been a long-standing and contentious issue. A substantive review was commenced in 2006; over fifteen years later, and at a currently operational cost of £3.6 million, aspects of the review remain incomplete and scrutiny of the system continues to identify profound failings (NIA, Citation2021; NIAO Citation2020). In the interim, a rolling number of measures have been introduced, including refinement of the categorisation system for recording SEN, an update of the graduated framework to support pupils and a revised Code of Practice. Additionally, an independent review of SEN has been commenced and is due to report later in 2022. There is an educational imperative for undertaking this analysis. To date, there has been limited comparative interrogation of SEN prevalence in NI relative to the UK and other jurisdictions, and little distinction of influencing factors at regional level. This paper aims therefore to present administrative data on the prevalence of SEN in NI, comparing it to rates of the other home nations in the UK; generate a useful evidence base upon which to build future data sharing as new data becomes available and accessible; and to demonstrate the utility of administrative data. The numbers of pupils with SEN in NI have increased in the past ten years at a rate that is proportionally higher than the general school population (DE Citation2019), and the percentage of pupils with SEN – including those with and without a statutory statement – has remained higher than in England (NIAO Citation2020). There have also been observable changes in the profile of these pupils. Evidence has established a compelling relationship between their educational profile and the wider circumstances of their lives, with higher rates of socio-economic disadvantage and lower rates of physical and mental well-being (Bunting et al., Citation2020; Equality Commission, 2015). More specifically, McConkey (Citation2020) reported that NI had the highest prevalence rates for autism over a nine-year period from 2010 to 2011, while a report by the NI Children’s Commissioner found that schools lacked the capacity and skill to support the increasing number of children with social, emotional and behavioural difficulties (NICCY, Citation2020).

The paper draws on and expands on data generated as part of an Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) longitudinal secondary data analysis project profiling pupils with SEN in NI (O’Connor et al., Citation2021). Using publicly available data produced by the Statistics and Research Branch of the Department of Education (DE), it has been possible to examine changes over time regionally and by school type and to consider these within the new SEN landscape. Decoding variable prevalence rates nationally and internationally is an intricate task, complicated by differing approaches to data collection and reporting, as well as approaches to assessment and identification of SEN. The complexity of accessing and interpreting diverse data sets is acknowledged at the outset.

National and International Trends

In NI, the term SEN describes children and young people with a learning difficulty which is significantly greater than the majority of children of his/her age, or who have a disability that prevents full use of educational facilities generally provided in schools (DE, 1996). The system for the assessment and identification of SEN broadly follows procedures elsewhere, with a sequential, staged process designed to establish if a child has a difficulty in accessing learning, if additional help in school is needed, what this extra support might be and if the issue of a statutory statement is required to meet their learning needs. Comparative prevalence rates for special educational needs and disability (SEND) are notoriously difficult to record precisely, with the arbitrary and contentious interpretation of data typically attributed to variations at the national level in measurements, classification and categorisation of need (DE Citation2022; UNESCO Citation2020; EASIE Citation2018b). At the European level, a comparison of learners with an ‘official decision of SEN’ (the equivalent of a statutory statement in NI) across 31 countries showed Sweden and Scotland at the opposite ends of a continuum (1% and 25%, respectively), with England and Wales at 3% each and NI at 5% (EASIE Citation2020). In the USA, the proportion of pupils receiving special education services is estimated at 15% (NCES, Citation2022), with a similar proportion identified in Australia (Australian Government Citation2020). To offset the complexity of ascertaining accurate international trends, the remainder of this section will focus on prevalence rates and changing trends in the rest of the UK. Governmental devolution means that each of the four nations (England, Wales, Scotland and NI) has decentralised power across a range of policy areas, including education, enabling this comparative analysis of NI SEN data and processes within the national context.

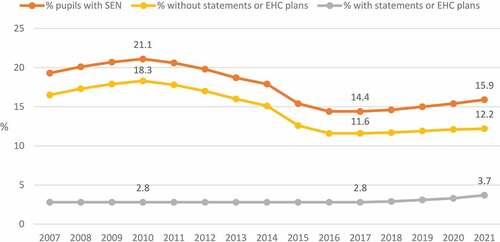

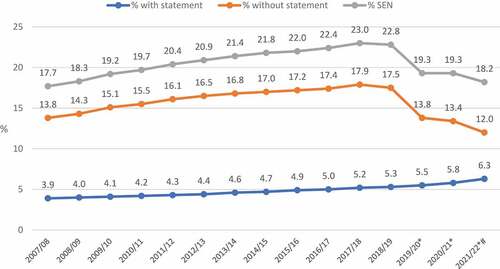

It has been over 40 years since the Warnock Report introduced the term ‘special educational needs’ into UK education policy and concluded that up to one in five children in the course of their school career were likely to need some special education provision (DES Citation1978; Black Citation2019). In England, the proportion of pupils with SEN has fluctuated, peaking at 21.1% in 2010 and decreasing to 14.4% in 2016 (Lindsay, Wedell, and Dockrell Citation2020) with current figures sitting at 15.9% in the 2020/21 school year. Changing rates have occurred alongside changes in SENDFootnote2 policy in England: between 2001 and 2014 provision comprised three stages, two at school level (School Action and School Action Plus) and a third legally based record of provision identified by formal assessment (Statement). These were combined into a classification of SEN support in 2014, via a SEND Code of Practice and Education, Health and Care Plans (EHC plans) (DfE Citation2015, Citation2019a; Black Citation2019). By the end of 2018, most pupils with Statements had been transferred to EHC plans (DfE Citation2019a). Black (Citation2019) noted that while this led to a dramatic drop-off in the number of non-statemented pupils, the numbers with EHC plans stabilised at 2.8% for a decade only to increase in recent years. By 2020/21, the proportion of pupils with EHC plans was at the highest rate (3.7%) since they replaced statutory statements (see ). The DfE (Citation2021a) attributed the overall decline in SEN rates to the better identification of SEN following a SEND review (Ofsted Citation2010) and the implementation of SEND reforms in 2014. At the time of writing, a further review of SEND in England has proposed earlier and greater consistency in how SEND is identified and supported; this includes quality universal services across education, health and care to ensure that pupils are not mis-labelled, a phenomenon generally attributed to inaccessible curriculum, ineffective teaching or weaknesses in service provision (Ofsted Citation2021). It remains to be seen how the roll-out of proposed changes will impact pupil outcomes and SEND prevalence.

Figure 1. % Students with SEN in England 2007-2021 Data source: 2007-2015 data from (DfE, Citation2019b) data tables. 2016-2021 from more recent (DfE, Citation2021b) data tables. Figures as of January each year.

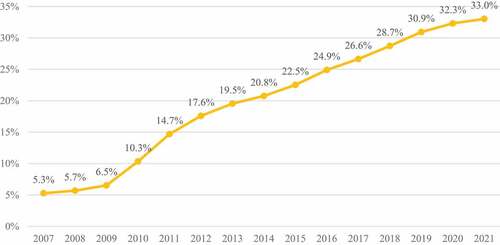

Recent trends in the proportion of pupils identified with Additional Support Needs (ASN) in Scotland have taken a very different trajectory to rates in England. Prevalence in Scotland has risen steadily year on year, from 5.3% in 2007 to 33% in 2021 (). In terms of SEN policy and legislation, Scotland diverged quite significantly from the other UK jurisdictions with the implementation of the Education Act (2004) and the replacement of SEN terminology with the more broadly defined ASN (Black Citation2019). ASN can arise for a range of reasons – the particular learning environment of pupils, wider family circumstances, disability or health needs, and social and emotional factors – each requiring additional support to help pupils reach their full potential (Eurydice Citation2019). Riddell et al. (Citation2019) considered that distinction in rates of ASN in Scotland and SEN in England was largely due to classification and recording differences. While England has 13 types of need to identify SEN, Scotland has 24 barriers to learning within ASN, which capture a wider profile of pupils, including looked after children and young carers.

Figure 2. Percentage of school roll with an ASN in Scotland 2007 - 2021Data source: Calculated based on total pupil numbers and total pupils with ASN from Pupil census 2021 supplementary statistics, available at https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/

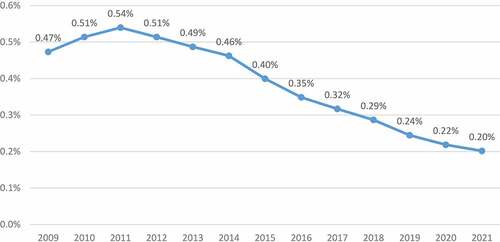

In contrast, the percentage of SEND pupils in England with statutory EHC plans is higher and has increased in the last few years, whereas the percentage of ASN pupils with statutory coordinated support plans (CSPs) in Scotland has declined steeply since 2011 (). In 2021, 3.7% of SEN pupils in England had EHCs, whereas only 0.2% of ASN students in Scotland had CSPs. One explanation is that there are only two types of support plans in England – statutory EHCs and non-statutory SEN support plans, whereas in Scotland, there are a range of ASN support plans of which only CSPs are statutory. Riddell et al. (Citation2019, 37) claimed that this distinction has important implications for pupils with the greatest needs, given that statutory support plans are essential to ensuring appropriate provision and upholding the rights of SEN/ASN pupils. Indeed, the Scottish Children’s Services Coalition (SCSC), an alliance of service providers that campaigns to improve services for vulnerable children and young people, voiced concerns over the decrease in legally binding ASN support plans (SCSC Citation2020; Meighan Citation2022). It was emphasised that, while a disproportionate number of ASN pupils came from the most deprived neighbourhoods, a lower proportion had received CSPs compared to pupils from more affluent areas. This has raised concerns that some pupils would not receive the legal support they are entitled to, a situation exacerbated by perceived local authority preference to use alternative less cumbersome and time-consuming support plans (SCSC Citation2020).

Figure 3. Percentage of school roll with a CSP in Scotland 2009-2021Data source: Calculated based on total pupil numbers from Pupil census 2021 supplementary statistics and number of pupils with CSPs compiled from annual Pupil Census Summary Statistics for years 2010 – 2021 available at https://www.gov.scot/publications/pupil-census-supplementary-statistics/

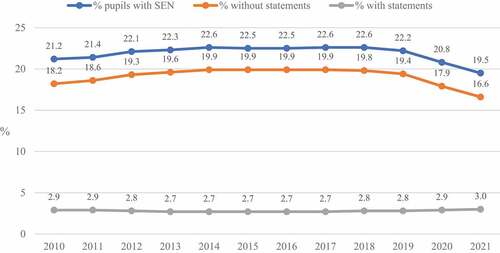

In Wales, the percentage of pupils identified with SEN has remained more stable compared to England and Scotland over the last decade or so (), ranging from a peak of 22.6% pupils in 2014, 2017 and 2018 before decreasing to 19.5% in 2021. The percentage of pupils with a statement of SEN has remained even more uniform at just under 3% over the same period. The system in Wales broadly followed that of England. Like EHCs in England and CSPs in Scotland, Statements in Wales are legally binding. Recent reform of the system introduced a change of terminology through the Additional Learning Needs (ALN) Act (2018) and a corresponding ALN Code (Citation2021). Although the legal definition of ALN is essentially the same as that of SEN, key changes included statutory individual development plans for all identified pupils, extension of the age range from 0 to 25 years and greater collaboration between local authorities and health boards (Dauncey Citation2018; Blenkinsop-Clarke Citation2021). The new ALN system is to be implemented between September 2021 and August 2024 (Welsh Parliament Citation2022); therefore, the longer-term implications of these changes in terms of ALN prevalence have yet to be seen.

Figure 4. % Students with SEN in Maintained schools in Wales 2010-2021Data source: Data as of January each year compiled from Welsh Government's school census results releases, available at https://gov.wales/schools-census-results/. 2010-2014 figures taken from 2014 release. Data is for maintained schools only, does not include data for independent schools. From 2017, percentages without statements are calculated from adding percentages with School Action and School Action Plus.

The prevalence of SEN in NI

About the data

Information on the proportion of pupils with SEN in mainstream Northern Irish schools is drawn from the DE’s annual school census data. It broadly replicates data collection elsewhere in the UK, although in England the additional SEN2 annual survey is a major source of data on pupils with EHC plans. The school census survey collects details on pupils enrolled on Friday of the first full week in October each year, typically recording a range of demographic characteristics including gender, religion, SEN status, ethnicity and Free School Meal Entitlement (FSME). While disaggregated SEN data (e.g. by overarching SEN category or individual SEN type) are available through a formal request to the Department’s Statistics and Research team, total pupil enrolment figures disaggregated at the upper level across school types are publicly available on the DE website. For the purpose of this paper, data have been compiled from corresponding publicly available statistical bulletins. The data cover the school years 2007/08 to 2021/22. In examining these prevalence trends, it is important to contextualise recent changes in SEN categorisation in NI that affect the comparability of the data across the study years. Limitations of the data are acknowledged; for example, due to data protection protocols, it was not possible to access individual pupil-level data which inhibited closer inspection of prevalence trends relative to other variables such as gender, FSME, and socio-economic status. Additionally, direct comparison across years is not possible due to changes in how SEN is identified and recorded. Nonetheless, there is clear potential to begin to monitor this as a policy imperative over the coming years informed, in part, by the changes noted in other UK jurisdictions.

From a five-stage to a three-stage approach

Recording of SEN in NI has been informed by procedures set out by the DE in its Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs and subsequent supplementary guidance (DE Citation1998, Citation2005). From 2010/11 to 2020/21, the identification and assessment of SEN followed a graduated five-stage approach. However, as of April 2021, a streamlined three-stage delivery was introduced within a draft SEN Code of PracticeFootnote3: school delivered special educational provision, school delivered with external provision from SEN services and school delivered plus SEN provision as set out in a statutory statement (DE Citation2021). Transition to the new system effectively has changed how pupils are placed on the SEN Register. For example, the needs of pupils formerly at Stage 1 will be reviewed to determine if they will continue to receive school-based or be removed from the SEN Register (DE Citation2021). Pupils at other former stages were automatically moved to the new Stages 1, 2 and 3, respectively, subject to external special educational provision (DE Citation2021). While all pupils with SEN continue to be recorded in the school census and are represented in departmental data reporting, the rationalised three-stage approach will have implications in terms of consistency and comparability between 2021/22 data and that of previous years.

Implementation of new SEN categories

A further factor affecting the consistency of data has been the implementation of a new SEN Register. During the time span of the original study (2010/11 to 2018/19), pupils with SEN were classified into seven overarching categories, subdivided into individual types of SEN (DE Citation2005). A complete review of SEN categories was undertaken in 2017/18, and a new listing has been in use since 2019. A key distinction of the new system has been the introduction of a Medical Register alongside the SEN Register. The revision sought ‘to promote a common understanding’ of SEN categories, including a distinction between pupils with SEN and those with a medical diagnosis (DE Citation2019, 7). Under the new system, pupils with a medical condition are placed on the Medical Register only, those with a SEN are placed on the SEN Register only and pupils with a medical condition who also require SEN provision are placed on both (DE Citation2019). This change has had implications for how SEN is recorded and reported. For example, Mild Learning Difficulties has been removed from the listing, while Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Attention Deficit Disorder/Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are categorised as medical conditions. It is too early to determine how the new categorisation system will (re)define data collection and reporting; recent data show that 17% of children with autism who previously would have been included in the overall prevalence rates were recorded on the Medical Register only as they had no co-occurring SEN (DoH, Citation2022) although it is not presumed that these pupils no longer require a form of educational support. Equally, any comparison with data collected before 2019/202 should be viewed in light of the revised categorisation that has implications for comparability across current SEN data and data collected before 2019/2020.

SEN rates in NI schools

As can be seen in , the overall proportion of pupils identified with SEN in NI has risen year on year from 17.7% in 2007/08 to 23% in 2017/18. However, changes to the identification and categorisation of SEN discussed above resulted in a notable drop in subsequent years, decreasing to 18.2% in 2021/22; this was matched with a slightly higher decrease in the proportion of pupils without a statutory statement, with a drop to 12.0% in the same time period. The current downward trend in the overall SEN rates is to be expected with the removal of a broad spectrum of medical conditions; however, in contrast, the proportion of pupils with a statutory statement has risen steadily over the past fifteen years, peaking at 6.3% in the most recent school year.

Figure 5. Overall % pupils identified with SEN in Northern Ireland 2007/08 - 2021/22Data source: DE NI School Enrolment Statistical Bulletins, available at https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/articles/school-enrolments-overview. Data for all schools and pre-school education centres (excluding hospital and independent schools). 2019/20 data is for all funded pre-school, nursery, primary, post-primary schools, and special schools * In 2019/20 there was a change in the categorisation of SEN. # In 2021-22 SEN are classified in 3 stages rather than the 5 stages used in previous years.

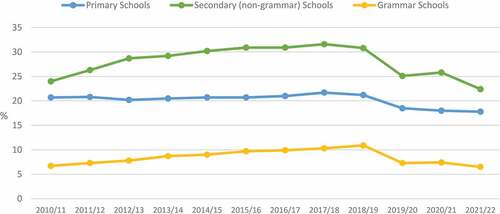

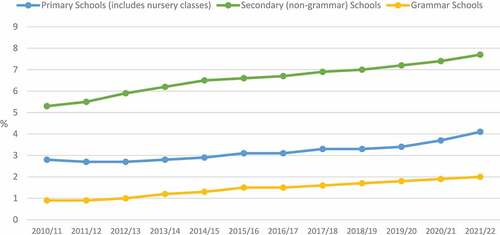

To better understand the distribution of SEN rates, presents data on total enrolment and SEN prevalence in primary, secondary and grammar schools. The total percentage of SEN pupils is shown as well as disaggregation by ‘statemented’ and ‘non-statemented’ status. While the overall prevalence rates of pupils with SEN increased until 2018/19 in post-primary secondary and grammar schools, the proportion in primary schools has remained relatively stable at around 21%. The overall decrease since 2018/19 is evident across all school types (), and this is closely aligned with a reduction in numbers of non-statemented pupils. Conversely, the prevalence rates for statemented pupils have continued to rise across school types (). The highest rate is in secondary schools, with an increase from 5.3% in 2010/11 to 7.7% in 2021/22. However, the analysis of prevalence rates proportionate to total pupil enrolment for each school type at the two time points provides additional distinction. In this instance, the contrast in prevalence rates shows a bigger difference in primary schools, with a 48% change in the numbers of statemented pupils, compared to a 38% change in secondary schools. While statemented pupil numbers are substantively smaller in grammar schools, there was nonetheless a difference of 80% proportionate to pupil enrolments at the two time points, reflecting a growing shift in the pupil profile in these schools.

Table 1. Prevalence of pupils with SEN in mainstream NI schools, 2010/11–2021/22.

Figure 6. % SEN Children by school type, all stagesData source: DE NI School Enrolment Statistical Bulletins, available at https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/articles/school-enrolments-overview

Figure 7. % SEN Children by school type, statementedData source: DE NI School Enrolment Statistical Bulletins, available at https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/articles/school-enrolments-overview

Discussion and Conclusion

The current Independent Reviews of Education and SEN in NI are once-in-a-generation opportunities to critically examine the efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability of education policy and provision in NI (DfE Citation2021b). However, the six-month time frame to complete the latter will arguably affect the extent to which the enduring legacy of unresolved issues can be fully addressed. In this regard, utilising contemporaneously available and accessible administrative data can generate insights, and evidence on the educational situation of these pupils highlights to meaningfully inform, frame and contextualise any policy-relevant discussion.

As identified, the method by which SEN data are collated, categorised and monitored is not a straightforward process. Although international instruments, such as the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, emphasise the value of disaggregated data to monitor inclusive education provision, the complexities of different frameworks and systems present challenges for interpreting comparable prevalence rates across countries. Arguably, the intricacy involved in analysis at this level impacts on universal understandings of SEN. In contrast, utilising data at the country level is an opportunity to benchmark SEN prevalence with precision and consistency and, from this, to extrapolate regional insights of particular relevance – actions that are not immediately evident in international data sets. In this respect, reporting on pupils with SEN in NI benefited from established statistical procedures for annual data collection at the pupil and school level which have provided comprehensive coverage of the school population over time. Although data at the individual level were not available for the original project, the longitudinal information at the school level nonetheless signposted revealing trends in the pattern of SEN incidence, which in itself is informative in terms of monitoring the pace and impact of SEN processes within new policy and legislative frameworks. As access to individual-level data becomes available, it will be possible to undertake further and more detailed analysis to extrapolate deeper associations in prevalence rates among this pupil population.

While the overall prevalence rate of SEN in NI has decreased in line with similar reform in other jurisdictions, the number of statemented pupils has continued to rise as evidenced earlier in the paper, with the current proportion well exceeding the anticipated ratio of 2.0% set out in the original Code of Practice (NIAO Citation2020). Various reasons have been proposed for these increases. Early intervention – particularly in pre-school and lower primary stage – has been highlighted as a fundamental building block for pupils’ development and longer-term prospects, yet there are currently little or no data that quantify the scale of need or gaps in provision (NIA, 2021). In the absence of meaningful data, it is difficult to gauge how timely and relevant support services for pupils with SEN will be identified. Similarly, insufficient access to Educational Psychology Services has a negative impact on the early referral process; critically, reliance on a time allocation model has effectively rationed the numbers of pupils who can access necessary specialist support, relegating some to lengthy waits, with a negative impact on educational outcomes (NICCY, Citation2020). In both instances, the imperative for improved provision is economically and educationally beneficial, offering immediate cost-effective solutions that could ultimately reduce the need for a statutory statement in the longer term (NIA, 2021; NICCY, Citation2020). Shortcomings at the systemic level have also meant that the number of parental appeals against decisions taken by the Education Authority (EA) has grown exponentially. Over the past five years, there has been a steady increase in the number of parents challenging statutory decisions around SEN, and a significantly high proportion is conceded in favour of the parent/carer before the matter proceeds to a tribunal hearing.Footnote4 The absence of an informed explanation from the EA for this trend further points to the need for improved systemic procedures and better synthesis of data across the SEN process.

The new categorisation system of the SEN and Medical Registers has undoubtedly affected the contextual trajectory of prevalence rates. It is highly likely that the decrease in prevalence rates among non-statemented pupils – which is where the biggest proportion is placed – relates to the placement of those with a medical condition only in a separate Register and schools moving to a more streamlined three-stage approach. Nonetheless, it would be informative to examine if and how these data have been deflated; in particular, where the analysis of overall trends can enable the better understanding of the pattern and spread of individual conditions. For example, research nationally and internationally has indicated increases over time in the prevalence of dyslexia (Knight and Crick Citation2021), speech, language and communication needs (Van Herwegen Citation2022) and intellectual disabilities (Zablotsky et al. Citation2019). The principle also applies to conditions now recorded as Medical and the placement of pupils on this register only. Reported increases in prevalence rates for ASD and ADHD (McConkey, Citation2020; Hire et al. Citation2018) reinforce the need for condition-specific data analysis not least since the presentation of these can continue to affect pupils’ access to, and experience of, education even if they do not have an identified SEN.

The scale and scope of big data sets have enabled in-depth exploration of associations between SEN prevalence and the wider circumstances of pupils’ lives over time and across a range of demographic and circumstantial variables – including age, gender, religion, ethnicity and socio-economic status. These correlations reveal strong patterns between SEN and social background (O’Connor et al., 2021), with implications for health, social care and education organisations who provide interventions and support continuously or at times throughout a pupil’s school career and beyond. The current state of SEN provision cannot be separated from educational and wider social and political contexts of Northern Ireland. In school terms, there is potential to explore trends in SEN at more discrete levels, for example based on school sector (distinguishing between pupils educated in denominational and integrated schools) as well as school type (distinguishing between pupils attending selective and non-selective schools). In social and political terms, there has been limited examination of the relationship between SEN and the legacy of a society in transition from conflict. While the association between SEN and social disadvantage has been reported elsewhere (Shaw, Citation2016), its nexus with the Troubles[2] provides a unique situational lens through which to better understand the continued high prevalence rates locally. Much of the most intense conflict was located within areas of the greatest social disadvantage which have remained largely unchanged in the intervening years. It would be useful, therefore, to identify and draw upon comparative data with another region in the UK with a broadly similar population density and socio-economic profile to differentiate the prevalence rates of SEN and distinguish any discernible causal factors with the period of the conflict in NI. More specifically, the Northern Ireland Census 2021 included a greater number of questions on learning disabilities providing, for the first time, an opportunity to extrapolate data on the gradient relationship between dimensions of SEN and a range of environmental variables. The availability of administrative data has been a step change in educational research to inform understandings of the sizeable, and growing, SEN pupil population. Its utility and contribution to policy discourse are likely to become increasingly important as new procedures become embedded.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the ESRC Secondary Data Analysis Initiative (Project No.: ES/S00601X/1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Special educational needs is the term currently used in Northern Ireland.

2. SEND is the term used in England.

3. The draft Code of Practice is available at https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/consultations/consultation-draft-sen-code-practice.

4. Freedom of Information request to the EA, April 2022.

References

- Australian Government. 2020. People with Disability in Australia. Web report. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/people-with-disability-in-australia/contents/education-and-skills/engagement-in-education [ Accessed 28.06.22]

- Black, A. 2019. “A Picture of Special Educational Needs in England–An Overview.” Frontiers in Education. Frontiers Media S.A 4: 79. doi:10.3389/FEDUC.2019.00079/BIBTEX.

- Blenkinsop-Clarke, K. 2021. ‘Leading Change: The Impending Changes of Additional Learning Needs in Wales’, ECSDN Student Papers.

- Bunting, L. M., C. Davidson, G. Grant, A. McBride, O., et al. 2020. The Mental Health of Children and Parents in Northern Ireland. Results of the Youth Wellbeing Prevalence Survey. Northern Ireland, Health and Social Care Board.

- Dauncey, M. 2018. Act Summary: Additional Learning Needs and Education Tribunal (Wales) Act 2018. Cardiff: National Assembly for Wales.

- DE. 1998. Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs. Bangor: Department of Education NI.

- DE. 2005. Supplement to the Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs. Bangor: Department of Education NI.

- DE. 2019. Recording SEN and Medical Categories - Guidance for Schools. Bangor: Department of Education NI.

- DE. 2021. Recording Children with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Schools-New Guidance-Move to Three Stages of Special Educational Provision, Circular Number: 2021/06. Bangor: Department of Education NI.

- DE. 2022. Annual Enrolments at Schools and in Funded pre-school Education in Northern Ireland, 2021-22. Bangor: Department of Education NI.

- DES. 1978. ‘Special Educational Needs: Enquiry into the Education of Report of the Committee of Handicapped Children and Young People (The Warnock Report)’. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

- DfE. 2015. Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-code-of-practice-0-to-25.

- DfE. 2019a. Special Educational Needs in England: January 2019. Darlington: Department for Education.

- DfE. 2019b. Special Educational Needs in England: January 2019, Department for Education. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england-january-2019.

- DfE. 2021a. Special Educational Needs: An Analysis and Summary of Data Sources. Sheffield: Department for Education.

- DfE. 2021b. Special Educational Needs in England: January 2021, Department for Education. Available at: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england.

- EASIE. 2018b. European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education:2016 Dataset Cross-Country Report. Edited by J. Ramberg, A. Lénárt, and A. Watkins. Odense, Denmark: European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education.

- EASIE. 2020. European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education: 2018 Dataset Cross-Country Report, European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Edited by J. Ramberg, A. Lénárt, and A. Watkins. Odense, Denmark: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education.

- Eurydice. 2019. United Kingdom - Scotland: Special Education Needs Provision within Mainstream Education. Available at: https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/special-education-needs-provision-within-mainstream-education-79_en (Accessed 7 May 2022).

- Hire, A. J., D. M. Ashcroft, D. A. Springate, and D. T. Steinke. 2018. “ADHD in the United Kingdom: Regional and Socioeconomic Variations in Incidence Rates Amongst Children and Adolescents (2004-2013).” Journal of Attention Disorders 22 (2): 134–142. doi:10.1177/1087054715613441.

- Knight, C., and T. Crick. 2021. The Assignment and Distribution of the Dyslexia Label: Using the UK Millennium Cohort Study to Investigate the socio-demographic Predictors of the Dyslexia Label in England and Wales. PLOS ONE. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256114

- Lindsay, G., K. Wedell, and J. Dockrell. 2020. “Warnock 40 Years On: The Development of Special Educational Needs since the Warnock Report and Implications for the Future.” Frontiers in Education 4 (January): 1–20. doi:10.3389/feduc.2019.00164.

- McConkey, R. 2020. The Increasing Prevalence of School Pupils with ASD: Insights from Northern Ireland. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(3), 414–424. 10.1080/08856257.2019.1683686

- Meighan, C. 2022. Scottish Children’s Group Warns Additional Support Needs Students Being ‘Failed’, The National. Available at: https://www.thenational.scot/news/19852532.scottish-childrens-group-warns-additional-support-needs-students-failed/ (Accessed 7 May 2022).

- NCES. 2022. Students with Disabilities. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg/students-with-disabilities.

- NIAO. 2020. Impact Review of Special Educational Needs. Belfast: Northern Ireland Audit Office.

- N.I.A. 2021. Report NIA 75/17-22. Public Accounts Committee. Report on Impact Review of Special Educational Needs. Belfast, Northern Ireland Assembly Commission.

- NICCY. 2020. Too Little Too Late. A Rights-Based Review of SEN Provision in Mainstream Schools. Belfast: NICCY.

- O'Connor, U. A., G. Ferry, F. McElroy, E. Mulhall, P. Murphy, J. Taggart, L., and R. McConkey. 2021. A Profile of Special Educational Needs in Northern Ireland Using Educational and Social Data. ESRC Report ES/S00601X/1.

- Ofsted. 2010. The Special Educational Needs and Disability Review: A Statement Is Not Enough. Manchester: Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills.

- Ofsted. 2021. SEND: old issues, new issues, next steps. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/send-old-issues-new-issues-next-steps/send-old-issues-new-issues-next-steps. [ Accessed 28.06.22]

- Prevalence of Autism (Including Asperger Syndrome) in School Age Children in Northern Ireland. 2022. Belfast: Department of Health.

- Riddell, S., Gillooly, A., Harris, N., Davidge, G. 2019. Autonomy, Rights and Children with Special Needs: A New Paradigm? The Rights of Children with Special and Additional Support Needs in England and Scotland (Swindon: ESRC)https://gtr.ukri.org/projects?ref=ES%2FP002641%2F1#/tabOverview) ‘Autonomy, Rights and Children with Special Needs: A New Paradigm? the Rights of Children with Special and Additional Support Needs in England and Scotland Report’.

- SCSC. 2020. Coalition Urges Action As Figures Highlight A More Than 50 Per Cent Drop In Legal Support For Children With Complex Needs, Scottish Children’s Services Coalition. Available at: https://www.thescsc.org.uk/coalition-urges-action-as-figures-highlight-a-more-than-50-per-cent-drop-in-legal-support-for-children-with-complex-needs/ (Accessed 7 May 2022).

- Shaw, B. 2016. Special Educational Needs and Their Link to Poverty. York, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- UNESCO. 2020. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All. Paris: UNESCO. doi:10.4135/9788132108320.n14.

- Van Herwegen, J. 2022. Why Has There Been a Rise in Number of SEN Children, Especially in the Early Years? London, UCL, Centre for Educational Neuroscience. http://www.educationalneuroscience.org.uk/2022/04/01/why-has-there-been-a-rise-in-number-of-sen-children-especially-in-the-early-years/.

- Welsh Parliament. 2022. The new Additional Learning Needs system: the tough task of implementation. Available at: https://research.senedd.wales/research-articles/the-new-additional-learning-needs-system-the-tough-task-of-implementation/ (Accessed 8 May 2022).

- Zablotsky, B., L. I. Black, M. J. Maenner, L. A. Schieve, M. L. Danielson, R. H. Bitsko, S. J. Blumberg, M. D. Kogan, and C. A. Boyle. 2019. “Prevalence and Trends of Developmental Disabilities among Children in the United States: 2009–2017.” Pediatrics 144 (4): e20190811. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0811.