ABSTRACT

In this study, we randomly assigned struggling readers in special needs education (n = 23; 8–12 years of age) to a dog-assisted reading intervention or a similar intervention without a dog present. Students participated in 30-minute reading sessions twice a week for a total of six weeks. Using two standardised tests we measured reading skills before, immediately after, and three months after the intervention. In addition, the task-related behaviours and emotional expressions of a sub-group of these students (n = 17) were observed during the sessions. Results show that students who received the dog-assisted intervention had a higher increase between the pre- and post-test in their reading scores on two standardised tests, for both single-word reading and full-text reading. Differences between the groups at the follow-up measurement were present, but not significant. Observations indicated that the group receiving the dog-assisted reading intervention showed a longer duration of on-task behaviour and positive emotions during the sessions. No differences in the duration of off-task behaviour and negative emotions were found.

In the last decade, poor reading outcomes have been documented in primary schools for special needs education in the Netherlands. On average, students read at a Grade-3 level when they leave special needs education, failing to reach the functional literacy level required for secondary education (Houtveen, Van De Grift, and Brokamp Citation2014). Similar findings have been reported in other countries, where the majority of students with learning or behavioural difficulties also read below the required levels (Hudson et al. Citation2020). Reading difficulties can negatively affect children’s wellbeing in school, later social and professional outcomes (Turunen et al. Citation2021), and increase the chance of developing emotional and behavioural problems (Francis et al. Citation2019).

To support struggling readers in special education, several remedial programmes or interventions have been established in which students spend extra time reading, playing word games, or selecting texts based on their interests. A reading intervention rapidly growing in popularity is dog-assisted reading. Although the specific setup and duration of dog-assisted programmes differ, they are all based on the premise that reading in the presence of a dog has a calming effect on struggling readers and contributes to their wellbeing. The dog is thought to provide a safe and non-judgemental context, especially when reading out loud, thereby contributing to the learning process of children with low self-concept, or those who have a hard time motivating themselves to read (Fung Citation2017). This would eventually lead to better reading scores.

Despite the growing number of dog-assisted reading programmes, research is scarce, especially in the special education context. A literature review from 2016 spanning several educational contexts concluded that many studies did not include a control group, randomly assigned participants to conditions, or used follow-up measurements to see if any effects were lasting (Hall, Gee, and Mills Citation2016). Studies after 2016 in mainstream education showed mixed effects. For instance, Kirnan, Siminerio, and Wong (Citation2016) studied the effects of a school-wide dog-assisted reading programme by comparing reading scores before and after the programme was installed, but only found a significant difference for kindergarten students. Connell et al. (Citation2019) randomly assigned 63 primary school students to a condition in which children worked together with a classmate to train a dog, read out loud with a classmate to a dog, and were working on classroom tasks with the dog simply present. Contrary to the expectations, children’s reading ability increased in all three conditions – even when children had almost no contact with the dog in the classroom condition. In the study of Barber and Proops (Citation2019), however, the reading performance of 11–12 year-old students (who read in counterbalanced order to a teacher and dog) was significantly better after reading to the dog. Yet, Schretzmayer, Kotrschal, and Beetz (Citation2017) only found modest effects on reading performance using a similar setup.

So far, only a few studies on reading dog programmes have been conducted with struggling readers or in special educational contexts, with mixed outcomes (Meixner and Kotrschal Citation2022). Le Roux, Swartz, and Swart (Citation2014) studied a 10-week programme in which 102 struggling readers were randomly assigned to sessions in which they read to a dog, an adult, or a teddy bear. The reading accuracy and comprehension scores of the students in the dog-assisted reading group showed a higher increase right after the intervention. Yet, the study of Uccheddu et al. (Citation2019) reported no significant differences when comparing the reading abilities of 5 students with autism who participated in a dog-assisted reading programme with the scores of 4 students with autism who read to an adult. Using interviews and classroom observations, Kirnan, Shah, and Lauletti (Citation2020) focused on special needs students’ behaviours in the presence or absence of a dog in the classroom. Although interviews with teachers indicated a positive influence of the dog on students’ behaviours, this could not be corroborated by the behavioural observations. In sum, although important pioneering work has been done studying reading dog programmes, research is scarce, especially in special education, with either small sample sizes or a lack of follow-up measures. Although one study focused on student behaviours in the presence of a dog, no studies have, so far, combined behavioural and reading measures.

Therefore, the current study examines the effect of a dog-assisted reading programme for students in three schools for special primary education by randomly assigning students to a six-week dog-assisted reading intervention or a similar intervention without a dog present. We measured reading skills before and after the intervention using two different standardised tests (single-word and full-text reading) and complemented these scores with behavioural observations during the sessions. We hypothesised higher gains in reading skills for the dog-assisted intervention group and more positive behaviours during the sessions in which a dog was present.

Materials and methods

Recruitment and participants

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the host university. Three Dutch special education schools for children with complex learning, behavioural, or emotional needs took part. Twenty-four students were selected by the school’s educational specialist to participate based on the following criteria: The student had a significant reading deficit of at least one year; were in (at least) second grade; their standardised reading test scores showed stagnation or deterioration between two consecutive test moments; the student had little or no pleasure in reading as indicated by the student or teacher; additional assistance had little or no effect, and the student was not diagnosed with dyslexia. Eligible students and their parents received an information letter and signed an informed consent.

One student dropped out before the start of the study, resulting in a sample of 17 male and 6 female students between 8 and 12 years of age (grade 2–6; n = 23). The percentage of females (26%) is representative of this type of special education in the Netherlands (Bronsveld-De Groot, Brandhorst, and Zweerink Citation2023). Participants’ median reading level at the start of the study was AVI-M4, which corresponds to mid-second grade. On average students had a reading deficit of 2.5 years.

Procedure

Students were matched on gender, age, and reading level, and then randomly assigned to a reading intervention with a dog and familiar teacher present (experimental group) or a reading intervention with only another familiar teacher present (control group). The experimental and control group consisted of three subgroups of 3–4 students each. All subgroups participated in the intervention twice a week for a total of six weeks (12 sessions). During 30-minute sessions, students joined their subgroup in a separate classroom.

In the first session, students chose an informative text – that appealed to them and that was slightly above their reading level – from a database with texts used to teach reading comprehension, such as human interest articles, backgrounds to the news, etcetera. In the intervention room, they discussed with the teacher how they could best read the text, and started reading in silence, underlining difficult words. During the second and third sessions, students read their own texts in silence, and then aloud for 5 minutes while the other students read their texts in silence. When reading aloud, the teacher helped each student to pronounce the difficult words they underlined. During the fourth session, students read their text aloud to the dog specifically (experimental group) or a fellow student (control group) while the other students kept reading their texts in silence. After this, a second and a third cycle of four similar sessions started.

The dog – a black Labradoodle of two years and nine months old – was present during all 12 sessions of the experimental group and was free to move around or lie down next to reading students. The dog had been present in the school for over 2 years, and was owned by a licenced teacher who guided the experimental group and who was also certified to perform animal-assisted interventions. Prior to the intervention, each subgroup met with the teacher and the dog to receive an explanation of the reading intervention. During this meeting, students were told that the dog calms down when students read to her. During the sessions, students were allowed to choose where they sat in the room, and were allowed to stroke or interact with the dog, as long as they kept reading and did not disturb others. Students played a short game at the end of each session. Students in the experimental group played this game with the dog, such as hiding a treat.

Measurements

Students were assessed using two standardised reading tests before (T1) and after the intervention (T2), and 3 months after the last session (T3). Both tests are also routinely administered as part of the national monitoring system and have received good reliability and validity scores from the Dutch Committee on Tests and Testing (Van Til et al. Citation2018). The AVI test is a standardised instrument measuring students’ reading ability by comparing it to the average reading development of children of the same age/grade in the Netherlands and Flanders. For instance, students are asked to read a text that the average student can read halfway through first grade; if they read this text at a sufficient pace without too many errors they are asked to read the text for the next level, and so on. Students are then classified according to the grade level of the text they mastered, ranging from halfway through first grade (AVI-M3) to the end of fifth grade (AVI-E7) or the highest level (AVI-Plus). The DMT test measures reading accuracy by counting how many single words a student can read without mistakes in three minutes. The student is given a card with rows of separate words of increasing difficulty and is asked to read aloud as many of those words as possible in one minute. This is repeated twice with words increasing in difficulty.

Next to the AVI and DMT standardised reading tests, a number of students were observed during the second and third sessions of the intervention, because these sessions had the most independent reading time and were similar for both groups, apart from the presence of the dog (recall that students spent some time in the first session to select a text and spent the last session either reading to a classmate or the dog, depending on the condition they were in). Using the ‘Behavior Observation Made Easy’ app on a smartphone (Shekhtmeyster Citation2018), each observer (n = 5) focused on one student. By means of tapping buttons, the app recorded the duration of on- and off-task behaviour, positive and negative emotions (). All observers received a codebook with behaviour descriptions and a short observation training. Because of practical reasons (observer availability, room size, school location), the number of observed students varied. Of the 11 students in the experimental group, four were observed twice and three were observed three times. Of the 12 children in the control group, four students were observed once, two students twice, and four students three times.

Table 1. List of observed student behaviours during the second or third reading session.

Analysis

The AVI test scores were converted to a number ranging from 1 to 11. After confirming that the normality assumption was not violated by examining QQ plots and the Shapiro-Wilk tests (all p-values > .05), the AVI and DMT reading tests scores of the experimental and control group were compared at T1, T2, and T3 using a repeated measures ANOVA. We used the partial eta squared (ηp2) as a measure of effect size. As a rule of thumb, ηp2 effect sizes > .13 are considered medium and > .26 as large (Cohen Citation1988). Despite a total sample size of 23, post-hoc power calculations in G*Power version 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al. Citation2009) revealed a high power (99%) because of the three repeated measurements and high correlations between these measures.

The observed task behaviours and emotions were converted into a proportion of the total observed time and, if needed, corrected for the time the student was out of sight. Because all students were observed during similar sessions while they worked on similar reading tasks, we collated the individual proportions into a mean percentage of on-task behaviour, off-task behaviour, positive emotions and negative emotions shown by the groups during the sessions. The median proportions were compared between the experimental and control group using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Reading tests

At the start of the study, the mean AVI and DMT scores were very similar. The mean AVI score at the start of the study did not differ between the groups, t (21) = .01; p = .99. This was similar for the mean DMT score, t (20) = .32; p =.75 (see ).

Table 2. Participant characteristics by group and mean reading test scores over time.

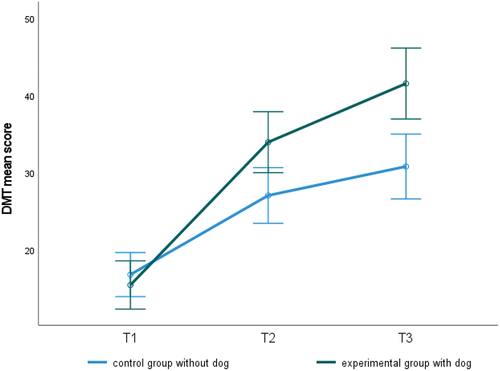

Both groups showed an increase in AVI test scores over time (). The increase over time was significant, F (2,42) = 22.69; p < .001 with a large effect size of ηp2 = .52. No overall group effect was found F (1,21) = .45; p = .51 and the overall interaction effect just fell short of significance, F (2,42) = 2.89; p = .07. Yet, follow-up tests showed that the two groups did significantly differ in their increase from T1 to T2 (F (1,21) = 4.93; p = .04; ηp2 = .19), but not in their increase from T2 to T3 (F (1,21) = .33; p = .58).

Figure 1. Mean AVI scores for the experimental and control group over time.

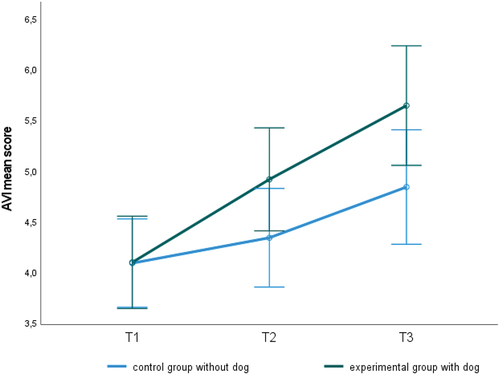

The mean DMT scores of the control group increased over time. For the experimental group, the increase was greater (). The results of the repeated measures ANOVA showed that the effect over time was significant, F (1.28, 25.64) = 58.92; p < .001 with a large effect size of ηp2 = .75. No overall between-group effect was found, F (1,20) = 1.25; p =.28. Yet, the interaction effect showed that the increase in DMT scores of the experimental group was significantly greater F (1.28; 25.64) = 5.27; p = .02 with a medium to large effect size of ηp2 = .21. This was mostly caused by a significant difference in increase from T1 to T2 (F (1,20) = 4.61; p = .04; ηp2 = .19). The increase from T2 to T3 (F (1,20) = 2.98; p = .1) fell short of significance.

Observations

The 7 observed students in the experimental group had physical contact with the dog for 5.98 minutes on average, which was initiated by the student 92.7% of the time. On average, students in the experimental group showed on-task behaviour 66.73% of the time (SD 7.79%), whereas students in the control group were on-task for 56.21% of the time (SD 13.12%). Students in the control group showed more off-task behaviour (16.37%; SD 9.47%) as compared to the experimental group (10.57%; SD 7.10%). The duration of positive emotions in the experimental group was longer (5.13%; SD 3.85%) than in the control group (.94%; SD 1.96%). Only a few negative emotions were observed, but these more often occurred in the control group (1.58%; SD 2.58%) than in the experimental group (.08%; SD .13%).

Mann-Whitney U tests indicated that the experimental group indeed had a longer duration of on-task behaviour (Z = 1.66; p = .049) and positive emotions (Z = 2.94; p < .01) compared to the control group. The duration of off-task behaviour (Z = 1.07; p = .14) and negative emotions (Z = .42; p = .34) did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Discussion

In this study, we randomly assigned 23 special needs education students (8–12 years old) to a dog-assisted small-group reading intervention or a similar intervention without a dog present. We used two standardised tests measuring single-word reading (DMT test) and text reading (AVI test). Although both groups increased in their reading scores over time, students who received the dog-assisted intervention showed a significantly higher increase between the pre- and post-test on both reading tests. The mean scores seemed to indicate that this difference was still present at the follow-up measurement three months after the intervention, but this fell short of significance. Observations of a subgroup of students (n = 17) indicate that the group receiving the dog-assisted reading intervention showed a longer duration of on-task behaviour and positive emotions during the sessions.

Although one might think that a dog could be a source of distraction – especially for students with complex learning, behavioural, or emotional needs – students seemed more focused in the experimental group. Other authors have commented that the presence of the dog has a relaxing effect and releases stress, thereby possibly allowing students to concentrate (Hall, Gee, and Mills Citation2016). This may be even visible on a physiological level, that is, the presence of a dog may have bodily effects such as an increase in oxytocin (Griffioen et al. Citation2023; Schretzmayer, Kotrschal, and Beetz Citation2017). In the current study, the positive behaviours that we observed during the sessions (longer focus and more positive emotions) might be the overt behavioural expressions of a possible relaxation effect of the dog, which may contribute to students’ reading development. We have to keep in mind, however, that both the dog and the students could decide where they positioned themselves in the room. Thus, during the silent reading in sessions 2 and 3, some students were sitting closer to the dog than others, and had more opportunity to touch or interact with the dog.

The current study is one of the first to look at follow-up outcomes measured after the ending of the intervention (Meixner and Kotrschal Citation2022). Such follow-up measures are important for policy reasons when deciding whether interventions are worth the investment. This study did not provide conclusive evidence for a long-term effect of the dog-assisted reading intervention. That said, we do not know whether a longer programme with more sessions would have contributed to a significant long-term effect.

The behavioural observations provide context and a first insight in what happens during the reading sessions, but were, nonetheless, limited. We encourage researchers to use this work as a foundation to build upon and improve our understanding of the mechanisms of dog-assisted reading, using more advanced observation schemes and other research methods, such as interviews on the students’ assumed role of the dog in their learning process (Jensen and Willbergh Citation2023). Notably, researchers could consider video-stimulated recall (e.g. Morgan Citation2007) in which students are asked to reflect on their reading to the dog while watching videos of this. This would provide insight into the lived experiences of students, which may help researchers to define what the added value of dog-assisted reading may be. For instance, is it having a close bond with the dog, a broader sense of social connection, or does the dog help students to maintain attention (Gu and Wright Citation2023)? Furthermore, the effect of the dog could be contrasted with other potentially soothing stimuli while reading, such as classical music.

While post-hoc calculations indicated this study had sufficient power, the sample is undoubtedly limited, with students coming from three primary schools for special education. Other limitations that need to be taken into account when interpreting our findings are that both the teachers administrating the reading tests and the observers were aware of the condition the student was in. At the same time, the random allocation after matching students on gender, age, and reading level of this study allows for more solid confirmation of the positive effects of dog-assisted reading interventions in special needs education.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank participating students and observers.

Disclosure statement

The third author (teacher) provides dog-assisted interventions on a regular basis and provided the experimental group sessions. This author was not involved in the analysis of the findings. No other potential competing interests can be declared.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barber, O., and L. Proops. 2019. “Low-Ability Secondary School Students Show Emotional, Motivational, and Performance Benefits When Reading to a Dog versus a Teacher.” Anthrozoös 32 (4): 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2019.1621522.

- Bronsveld-De Groot, M., B. Brandhorst, and J. Zweerink. 2023. “Vergelijking Populaties Gespecialiseerd Onderwijs en Basisonderwijs [Comparison Populations in Specialised and Mainstream Primary Schools].” https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/longread/aanvullende-statistische-diensten/2023/vergelijking-populaties-gespecialiseerd-onderwijs-en-basisonderwijs.

- Cohen, J. 1988. “Set Correlation and Contingency Tables.” Applied Psychological Measurement 12 (4): 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168801200410.

- Connell, C. G., D. L. Tepper, O. Landry, and P. C. Bennett. 2019. “Dogs in Schools: The Impact of Specific Human–Dog Interactions on Reading Ability in Children Aged 6 to 8 Years.” Anthrozoös 32 (3): 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2019.1598654.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A. Buchner, and A. G. Lang. 2009. “Statistical Power Analyses Using G* Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses.” Behavior Research Methods 41 (4): 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

- Francis, D. A., N. Caruana, J. L. Hudson, and G. M. McArthur. 2019. “The Association Between Poor Reading and Internalising Problems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Psychology Review 67:45–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.09.002.

- Fung, S. C. 2017. “Canine-Assisted Reading Programs for Children with Special Educational Needs: Rationale and Recommendations for the Use of Dogs in Assisting Learning.” Educational Review 69 (4): 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1228611.

- Griffioen, R. E., G. J. M. van Boxtel, T. Verheggen, M. J. Enders-Slegers, and S. Van Der Steen. 2023. “Group Changes in Cortisol and Heart Rate Variability of Children with Down Syndrome and Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder During Dog-Assisted Therapy.” Children 10 (7): 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071200.

- Gu, J., and S. Wright. 2023. “Does Reading Aloud to a Dog Improve Children’s Reading Outcomes? An Academic Critique.” DECP Debates 1 (185): 22–41. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsdeb.2023.1.185.22.

- Hall, S. S., N. R. Gee, and D. S. Mills. 2016. “Children Reading to Dogs: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” PloS One 11 (2): e0149759. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149759.

- Houtveen, A. A. M., W. J. C. M. Van De Grift, and S. K. Brokamp. 2014. “Fluent Reading in Special Primary Education.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 25 (4): 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2013.856798.

- Hudson, A., P. W. Koh, K. A. Moore, and E. Binks-Cantrell. 2020. “Fluency Interventions for Elementary Students with Reading Difficulties: A Synthesis of Research from 2000–2019.” Education Sciences 10 (3): 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10030052.

- Jensen, A. R., and I. Willbergh. 2023. “The Dog as an Unaware Pedagogical Agent in a School Reading Course.” Anthrozoös 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2023.2232657.

- Kirnan, J., S. Shah, and C. Lauletti. 2020. “A Dog-Assisted Reading Programme’s Unanticipated Impact in a Special Education Classroom.” Educational Review 72 (2): 196–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1495181.

- Kirnan, J., S. Siminerio, and Z. Wong. 2016. “The Impact of a Therapy Dog Programme on Children’s Reading Skills and Attitudes Toward Reading.” Early Childhood Education Journal 44:637–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0747-9.

- Le Roux, M. C., L. Swartz, and E. Swart. 2014. “The Effect of an Animal-Assisted Reading Programme on the Reading Rate, Accuracy and Comprehension of Grade 3 Students: A Randomized Control Study.” Child & Youth Care Forum 43:655–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9262-1.

- Meixner, J., and K. Kotrschal. 2022. “Animal-Assisted Interventions with Dogs in Special Education—A Systematic Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:876290. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.876290.

- Morgan, A. 2007. “Using Video-Stimulated Recall to Understand Young Children’s Perceptions of Learning in Classroom Settings.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 15 (2): 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930701320933.

- Schretzmayer, L., K. Kotrschal, and A. Beetz. 2017. “Minor Immediate Effects of a Dog on Children’s Reading Performance and Physiology.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science 4:90. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2017.00090.

- Shekhtmeyster, Z. 2018. “Behavior Observation Made Easy. (Version 2.5) [Mobile App].” https://www.behaviormadeeasy.com/.

- Turunen, T., E. Poskiparta, C. Salmivalli, P. Niemi, and M. K. Lerkkanen. 2021. “Longitudinal Associations Between Poor Reading Skills, Bullying and Victimization Across the Transition from Elementary to Middle School.” PloS One 16 (3): e0249112. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249112.

- Uccheddu, S., M. Albertini, L. Pierantoni, S. Fantino, and F. Pirrone. 2019. “The Impacts of a Reading-To-Dog Programme on Attending and Reading of Nine Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Animals 8:491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9080491.

- Van Til, A., F. Kamphuis, J. Keuning, M. Gijsel, J. Vloedgraven, and A. de Wijs. 2018. Scientific Justification for LVS DMT Testing. https://cito.nl/media/2juinmdl/106-cito_lvs-dmt_gr-3-tm-halverwege-gr-8_wet-verantwoording.pdf.