ABSTRACT

Although some European countries have initiated systemic transformation towards inclusive education since the ratification of the CRPD, the Austrian school system persists in the segregation of mainstream and special schools and is administered by the allocation of special educational needs (SEN). The SEN assessment attempts to provide individual support to foster pupils’ learning by diagnosticing disabilities and deviant behaviour. This circumstance contradicts an understanding of inclusive education without medical and psychological orientated categorisation. The multi-perspective case study contributes to the debate on the requirements of inclusive education and the SEN assessment using the methodological approach of Situational Analysis to understand the experiences of teachers within the inclusion assessment complex. The article follows the research question: How do teachers deal with the dilemma resulting from the requirements of inclusive education and the SEN assessment in Austria? The data set consists of seven focus group discussions with 21 stakeholders (administrators, teachers, and pupils). The findings show that the renewed SEN policy and assessment caused several dilemma. Negotiating this ambiguity is highly dependent on how teachers understand inclusion and to what extend they use their autonomy and discretion to enable inclusion in pedagogical settings.

Introduction

Governments oversee education by managing schools and assessments to track and evaluate how students are learning. The Special Educational Needs (SEN) label is a key indicator of students’ performance and abilities in Austria and other countries. Since its introduction in 1985, the percentage of students with SEN has remained unchanged (Statistik Austria Citation2024). This stagnation persists despite international documents such as the Salamanca Declaration of 1993, the UN-CRPD of 2006, and the Agenda 2030, which advocate for systemic and institutional transformations.

This article analyses the current situation vis a vis the inclusion assessment framework. This framework is shaped by Special Educational Needs (SEN) assessment policies and the concept of inclusion based on human rights. We explore the relationships between education policies, bureaucratic administration and the role of teachers within this context (Lipsky Citation1969). Through application of the Situational Analysis methodology (Clarke, Friese, and Washburn Citation2022), we find that teachers face risks of mental stress when their views conflict with the institutional policies, such as the Austrian agenda of school inclusion as administrative placement. The extent to which teachers are able to navigate this conflict is highly dependent on their worldviews, including their ideas of inclusion, and to what extent they use their autonomy and discretion to enable inclusion in practice.

SEN policies and assessment in austria

Although all countries in Europe use assessments to evaluate pupils’ performance, competences, and ability, they fundamentally differ in aims, policies, and implementation (EASNIE, Turner-Cmuchal and Lecheval Citation2022; Schwab Citation2020). According to Gitschthaler et al. (Citation2021), ‘the implementation of inclusive education systems’ and thus assessment should be ‘a European shared policy goal’ (p. 67). Ebersold and Cor (Citation2016) attribute the lack of systemic and institutional transformation in European education systems to legislative and funding models inherited from the 1990s or earlier.

If we turn to the history of inclusive education, we find that the School Organisation Act of 1962 established the legal basis for Austria’s two-track school system (Buchner and Proyer Citation2020). The nationwide implementation of special schools aimed to educate pupils deemed unsuited for mainstream schooling. Following the 1994 Salamanca Declaration, a paradigm shift introduced strategies, policies, and practices to support students with disabilities in mainstream schools with additional resources (Buchner and Proyer Citation2020). Legislation in 1993 and 1996, as the 15th and 17th amendments to the Austrian School Organisation Act, gave parents the right to choose between mainstream and special schools (Buchner and Proyer Citation2019, 86). The Compulsory Education Act of 1985 allows parents or school heads to request SEN services from the local school authority if a pupil cannot follow the mainstream curriculum despite full pedagogical interventions (BMWFW, Citation2023).

A second international policy milestone, the CRPD, has challenged SEN policies worldwide. Its ratification in 2008 obligated Austria to implement inclusive education, bringing new dynamics into the discourse on the quality of inclusive education and the existence of special schools (Buchner and Proyer Citation2019, 88). The National Action Plan Disability 2012–2020 (NAP) did not reform SEN assessment methods (Biewer et al. Citation2020). In 2018, the nationwide policy reform, Education Package 2018 (in German Bildungspaket 2018), reorganised school inclusion by establishing Units for Inclusion, Diversity, and Special Education within the mainstream school authority. These Units employ ‘diversity managers’ responsible for executing SEN assessments. The SEN assessment procedure now involves three steps: (1) disability identification, (2) curriculum identification, and (3) placement identification according to the policy paper Rundschreiben 2019). In Austria, unlike other European countries, a medical diagnosis is mandatory for allocating an SEN label.

Research on the inclusion assessment complex

The scientific debate on promoting inclusion by assessing pupils’ educational needs is manifest in the inclusion assessment framework. Two fundamental issues are evident: (1) the consideration of human diversity and its complexity in policies and practices, and (2) the construction of boundaries that mirror the degree to which otherness is acceptable within a defined system (Ydesen et al. Citation2022). Both issues ‘are highly dependent on cultural decisions, that is, what and who is to be assessed/included, how to assess/include, and what the implications should be in terms of policy and practice’ (Ydesen et al. Citation2022, 2). A European study compared inclusion policies and practices with the result that education policies still promote the two-track education system, consisting of mainstream and special schools, in countries in which the proportion of students with diagnosed SEN is 1.2% or greater (Schädler and Dorrance Citation2012), including Austria with around 1.5% (Statistik Austria Citation2024).

Contemporary research reveals a mixed picture when it comes to theoretical and empirical contributions to the literature since Austria initially introduced the SEN policy in 1993. The SEN assessment reinforces the medical view of disability and constitutes the tensioned field between exclusion and inclusion (Feyerer Citation2009; Grubich Citation2011). Both of the aforementioned scholars criticised the lack of objectivity and transparency within the SEN assessment procedures. Feyerer (Citation2009) highlighted, for instance, the risk of institutionalised discrimination, especially for pupils with a migration background. Seyda (Citation2020) researched the overrepresentation of migrants in special education, arguing that (institutional) mistrust determines the SEN assessment procedures.

A handful of studies addressed the SEN assessment directly, emphasising its time-consuming nature and lack of accountability due to insufficient analytical methods and assessment documents (Ansperger, Wetzel, and Sauer Citation1999; Hartmann and Urban Citation2011). Klicpera and Klicpera-Gasteiger (Citation2006) confirmed this, attributing the lack of systematisation to special educators’ insufficient knowledge. Scholars speculated that delays were often caused by parental disagreements with authorities. They also criticised disparities between Austrian federal states, resulting in varying integration rates. Krammer et al. (Citation2014) found that SEN assessments for learning disabilities focus more on poor academic and language skills and deviant behaviour than on psychiatric measures like IQ. Schwab et al. (Citation2015) noted that while the quantity of assessment reports doubled, the number of pupils assigned SEN remained stagnant over 10 years, due to fewer specialists writing more reports (Schwab et al. Citation2015., 328). The latest evaluation highlighted two fundamental ambivalences in the SEN assessment procedure: first, defining disability as a monocausal derivation of abilities in the mainstream classroom contradicts international human rights and scientific knowledge; second, an inadequate definition of SEN leads to tautological reasoning, which ‘merely repeats what is to be defined without making a substantive statement’ (Gasteiger-Klicpera et al. Citation2023, 235). Both ambivalences foster an anti-pedagogical attitude within the SEN assessment procedure.

Research gap, question, and the aim of the study

Against the background of the outlined tension between the international right to inclusive education and the conflicting SEN education policies and assessment practices in Austria, it is important to study the inclusion assessment framework with the aim of reducing educational inequality, exclusion, discrimination, and stigmatisation. A review of state-of-the-art literature reveals a lack of fundamental educational research after the policy reformation of 2018/19 in Austria. The role of mainstream teachers has not yet been sufficiently researched, despite the fact that they are pivotal facilitators for implementing inclusive education on the ground. In view of this research gap, the following research question guides this article:

How do teachers navigate the dilemmas arising from the mandate for inclusive education when SEN assessment in Austria continues to be non-inclusive?

The paper contributes to the scientific debate around the inclusion assessment framework. The multi-perspective case study maps the complex situation of implementing inclusive education and assessing pupils diagnostically with the SEN assessment, offering insights into teachers’ roles within the inclusion assessment complex in Austria.Footnote1

Theoretical background of the inclusion assessment complex

Inclusion and assessment are vexed topics in educational theory and practice (Ydesen et al. Citation2022). How we conceive of inclusion, both in its meaning and its value, is key to providing robust theoretical grounding that guides practice. Göranson and Nilholm (Citation2014) identified four different definitions of inclusion in high-impact research, all of which have fundamentally different implications for researching the inclusion assessment framework.

illustrates what the placement definition describes as ‘inclusion as the placement of pupils with disabilities/in need of special support in general education classrooms’ (268). It focuses on placement options in Austria, consisting of either mainstream or special schools. Ahrbeck (Citation2016), for example, argues that placement in a special school constitutes inclusion if it best meets the needs of the pupils. The act of placement requires the identification of an SEN that establishes a difference between pupils (Norwich Citation2008; Skrtic Citation1991), identifying some students as deficient or disabled with respect to a defined norm (Oliver Citation2013).

The second definition shifts focus from placement to pupils’ needs. The specified individualised definition defines ‘inclusion as meeting the social/academic needs of pupils with disabilities/pupils in need of special support’ (268) and is contextualized within the SEN discourse. Since it focuses on some pupils with predefined characteristics in mainstream schools, SEN (re)produces the dilemma of difference, giving rise to the question of ‘whether to recognise or not to recognise differences, as either option has some negative implications’ (Norwich Citation2010, 116). However, the SEN categories, which make the distinction between ‘normal’ and ‘special’, manifest the ‘machine bureaucracy of educational administration’ (Nilholm Citation2021, 361 following Skrtic Citation1991). Clark et al. (Citation1999) present SEN assignments as being ‘artefacts of practices in ordinary schools which can ultimately be traced back to organisational characteristics of those institutions’ (158). Both definitions ‘demonstrate a narrow view of inclusion as they refer only to students with disabilities, while the next two [definitions] refer to [a broad view on] inclusion that aims to meet all students’ needs and create inclusive communities’ (Ydesen et al. Citation2022, 70).

The third definition, the general individualised definition, goes beyond the SEN discourse but still focuses on pupils’ needs, describing inclusion as meeting the social/academic needs of all pupils (268). It requires a structural modification of education to better adapt to all pupils’ needs (Thomazet Citation2009, 558). The fourth definition, the community definition, promotes inclusion as the creation of communities with specific characteristics (558). Both definitions are contextualised within the mainstream education discourse, but the community definition looks beyond the restricted focus on pupils’ individual needs to the broader learning environment. Education forms the foundation of school inclusion, aiming to ensure that all pupils learn together regardless of disabilities or other social inequalities (Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006; Florian Citation2014). However, tension between exclusion and inclusion goes beyond institutional segregation, as communities define themselves through commonalities and construct boundaries through differences manifested in administrative bureaucracy (Ydesen et al. Citation2022). Both the third and fourth definitions of inclusion require not only a paradigm shift in policies and practices (Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006; Slee Citation2011) but also in the organisational paradigm (Clark et al. Citation1999, 158).

Methodological approach

Data & participants

The secondary analysis considers the Austrian data of the Erasmus+ project I AM, consisting of seven focus group interviews (FG1 to FG7) conducted in Vienna by the Austrian project team. Our participatory research group consisted of two university researchers and two mainstream teachers partly employed at the university. The group applied the overarching methodology, namely the situation analysis described by Clarke et al. (Citation2022). The methodology legitimises the sample size of seven focus group discussions. The deciding factor is the systematic exploitation of the data and not the sample size (s. next subsection). shows the relevant demographic information.

Table 1 Demographic information of the empirical data.

The interviews were conducted between June and December 2021, varied between 35 and 70 minutes, and some were held online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A semi-structured interview guideline outlined the topics of general assessment practices and SEN assessment in particular. We serially numbered the focus group discussions, indicating that they involved the same participants as follow-ups. With a more focused interview guideline, subsequent discussions investigated assessment practices in line with the project’s goal to make an ICF-based assessment tool (Barbour Citation2014). Both conducting periods gathered multi-perspective insights around the inclusion assessment complex.

To comply with ethical guidelines for educational research, informed consent guarantees anonymity and confidentiality of data that was obtained from all participants. As the pupilsFootnote4 were between 10 and 12 years old, we sought and acquired the informed consent of their parents.

Data analysis

We chose the postmodern take on Grounded Theory referred to as Situational Analysis (Clarke, Friese, and Washburn Citation2022). This approach allowed us to explore the inclusion assessment framework and to investigate the relationship between inclusion and assessment, drawing out the teachers’ role within the framework. The verbatim transcribed material was coded and prepared using MAXQDA software. The data were analysed chronologically according to the time of conduction. We used the open access online visual workspace MIRO to manage the analysis. Digital memoFootnote5 writing helped us to collect thoughts and to formulate questions aimed at ascertaining the relationships between the key elements. Following the method, we applied the six mapping strategiesFootnote6 in four two-hour workshops in the second project year, 2022. Each strategy revealed key elements and detailed information by progressively reaching theoretical saturation. Theoretical saturation was reached when the research process no longer revealed new key elements and information, which result was verified by switching between mapping strategies 2 and 5. At this point, we decided to use mapping strategy 6 to create the Project Map as the final output.

Empirical findings

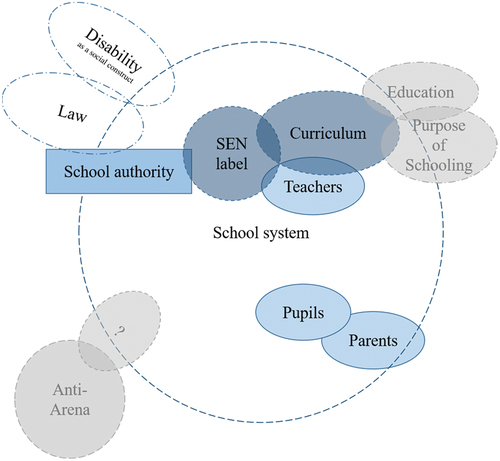

s an introduction to this section, we first provide an overview of the selected findings that describe the structure of the inclusion assessment framework in the context of Austrian schools. These key findings became visible for the first time in mapping strategy 4, the Social Arena Map (). shows the school system as the central arena. The other arenas placed around depict a wide range of key elements (marked in italics) such as social groups or theoretical and philosophical core principles.

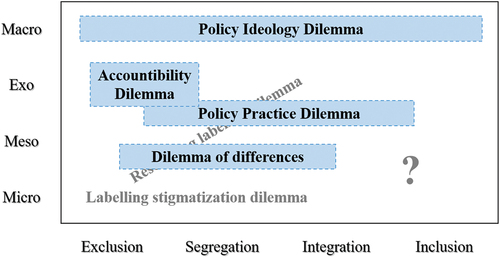

In order to cluster the arenas in a meaningful way, we decided to use a systemic approach from the macro to the micro levels. This allowed us to follow the aim of investigating the inclusion assessment complex holistically. This systematisation was the starting point for one axis of the Position Map ().

The other axis is based on the remaining areas that deal with the theoretical and philosophical core principles which constitute the discourses from exclusion to inclusion (Allman Citation2013; Göranson and Nilholm Citation2014).

Policy ideology dilemma – inclusion as a matter of definition

The Social Arena Map visualises the school system and its ability to define what is included. The school system stands for the ideologies that constitute both policy and practice in Austria. The following conversation between two teachers exemplifies the diversity of ideologies within the inclusion assessment complex (S1, T2 & T3, FG1).

T3: So, how do I address something like that, how do I address diversity, everyone is different, and how do I name it? Do I say you have a disability? I do not know. I am sensitive about it. It is in our society-

T2: Because it is a problem in our society. That is the main problem-

T3: Exactly.

T2: It [inclusion] is written everywhere, but it is not socially lived.

The quotation indicates, on one hand, a high degree of sensitivity to the impact of wording, and, on the other hand, a fundamental confusion of terminologies around the phenomenon of inclusion. Both teachers seemed to share an idea of inclusion, which does not necessarily match the SEN policy definition. This confusion causes the policy ideology dilemma at the macro level. The identification of the underlying ideologies, and thus the ideas of inclusion that influence policies and practices, is necessary for the analysis of assessment practices.

Accountability dilemma – SEN as an attempt to measure inclusion

As the executive bureaucratic body of the Austrian state, the implementation of this finding requires the engagement of the school authority. Situational Analysis showed the diversity managers to be silent actors who play a major background role and occupy a powerful position, deciding on when the SEN label should be applied and thus being the final arbiter on decisions of inclusion and exclusion. The upcoming text fragment illustrates the organisation of the school authority, from which we derived the ideology that underlies the law and policy reformation of 2018.

We are three diversity managers with different areas of expertise. My area is mental retardation and learning, A3’s area is autism only, and A2’s area is a lighter form of SEN. We work similarly, but with different tools to assess things. (B, A1, FG1)

The school boards do not provide any standardised procedures. Each diversity manager invents his or her measures and instruments developed and based on the curriculum. (B, A1, FG1)

The workforce is organised around areas of expertise based on neuropsychiatric-oriented medical diagnoses. Structurally, the workforce is explicitly subject to the medical model of disability rather than the social model of disability (Oliver Citation2013), not to mention inclusion-orientated approaches beyond disability categories. Nevertheless, A1 mentioned exercising discretion by using individualised methods for SEN assessment. In this way, they distanced themselves from the school authority, criticising the lack of guidelines and highlighting the need to take personal responsibility. The next quote confirms the discretionary scope in the light of the inclusion-oriented methods that were applied.

The school psychologist creates the ICD-11 diagnosis. We [diversity managers] are the ones who assess the child´s level of learning with standardized tests, with classroom observation. […] And, we write […] normal reports. We are on the way to making them [the reports] ICF-based. (B, A10, FG2)

The diversity manager distanced her/himself from the requirement of a medical diagnosis because s/he emphasised that the diversity managers had assessed the pupil differently. The use of the word ‘normal’ as synonymous with ‘pedagogical’ confirms the pattern of accountability in this context. To increase the reliability, A10 explained that the SEN assessment had proved its accountability by its systematisation and transparency. The latter statement suggested a certain incompatibility between the current SEN reports and the interviewee’s idea of how inclusion could be increased.

However, the quotes reveal a contradiction: A1 reported a lack of standardised procedures, whereas A10 considered them already established. These very inconclusive findings point to the bureaucratic attempt to create reliability and accountability by measuring inclusion with the SEN assessment procedures. Our Situation Analysis further revealed the link between the dilemma of accountability at the exo level and the meso level, respectively, as addressed in the next subsection.

Policy practice dilemma – discrepancy between administration and pedagogy

The Position Map locates the policy practice dilemma between the exo and the meso levels, which is best exemplified with reference to the teachers’ role from the diversity manager’s perspective:

Teachers have to make a learning assessment, make an error analysis, that they then create a support plan, so to speak, that they should change the method to make the children learn. (B, A1, FG1)

A1 unequivocally allocates the responsibility for pupils’ academic success to teachers’ professional skills. However, the upcoming text fragment represents the teachers’ insecurity regarding their responsibility within the inclusion assessment framework:

I find it difficult to define what my responsibility is. What actually is my area of responsibility? I find incredibly difficult. Um, and I noticed that I face this repeatedly. […] and it is not so […] clear. You have to define it for yourself. (S1, T3, FG1)

This person showed how crucial was the question of responsibility, and with it question of how tasks are distributed. T5 emphasised this point: ‘You mean that people would think you are a bad teacher because so many [pupils] are not supported?’ (S2, T5, FG1) Both quotes illustrate the policy practice dilemma due to the discrepancy between the provision of additional pedagogical support in the mainstream classroom and the initiation of the SEN assessment procedure.Footnote7 In this way, teachers’ professional commitment to support pupils to the best of their ability stands in tension with, so to speak, submitting pupils to the diversity managers. At the point at which teachers are required to use their pedagogical discretion, the only way they can exercise this is by issuing pupils with a negative grade. This is a prerequisite for the initiation of the SEN assessment.

I think when it comes to the SEN assessment, it would be important that we become a bit more flexible again. Pupils should not have to go through standardised programs. That we become a little more individualised again. (S1, T2, FG1)

This text fragment suggests the interpretation that the renewed SEN assessment procedure did not meet the teachers’ needs at the meso and micro level. T2 indicated that the SEN assessment is too rigid due to the administrative demands. The interviewee indirectly reproached the superior authority or the upper echelons of the system for mismanagement and, simultaneously, urged for a higher degree of autonomy and discretion for teachers. At this stage in our analysis, the SEN assessment has not revealed any pedagogical characteristics, which opens space for the following interpretation. The teacher might have criticised the anti-pedagogical attitude in the SEN assessment from their professional standpoint, corresponding to the dilemma of differences on the meso and micro levels.

The dilemma of differences – mental threats for teachers and pupils

The renewed SEN assessment highlights the dilemma of differences. One teacher outlines the interdependencies between the SEN label and the curriculum: ‘This child has special needs. The child needs a different curriculum because it cannot follow the mainstream curriculum’ (S1, T1, FG1). The choice of words (‘has’) suggests that the pupil has a bodily disability without hope of a cure. The pupil’s perspective confirms this: ‘Some children have that [additional lessons] where their parents register them. Pupil C, for example, has that and she does not like it at all’ (S1, P1, FG1). The pupil was referring to a peer attending additional lessons, constructing a boundary between the two students. Additionally, P1 showed empathy as they realised that the peer didn’t enjoy the additional lessons. The pupils seemed aware of the segregated structures reproduced by implementing additional lessons based on the special curriculum and the SEN label.

The following findings show that the dilemma of differences raises a real risk of mental stress. It was a burden to me. The fact that [the SEN assessment] procedures run so slowly until at some point someone comes and assesses the child. […] The child has been already graded as insufficient for the third year because of the wrong curriculum. (S1, T3, FG1) T3 thus reproached the higher powers for mismanagement. The long administrative delays can technically be explained by the reformed SEN policy, which is the legal mechanism for the enforcement of bureaucratic power. The next two quotes demonstrate the impact of the inadequate administration on the pupils from the teachers’ perspective:

If a pupil is graded as insufficient, it has an impact on the student. If s/he perform in the best possible way, so to speak, but simply cannot keep up due to the circumstances. Because s/he is simply being taught in the wrong curriculum. And yes, I think, that is the issue what happens to you when you have to continue with something that is not designed for you. (S1, T2, FG1)

T2 addressed the risk of pupils’ devaluation, rejection, and therefore discrimination and stigmatisation. According to T2, the school system has provoked failure and placed the burden of inadequate administration on teachers and pupils. This further confirms the incorporation and reinforcement of the medical model of disability as illustrated by the following quote (S1, P2 & P4, FG1):

P2: We are, Pupil 1 and I, not registered [for the additional class]. It [the additional class] is for dyslexics.

P4: Yes, so, it is for me. I am dyslexic. But it will stop soon, hopefully’.

P2 highlighted the constructed differences between P4 and themselves caused by the curriculum. They explained that the additional lesson is for dyslexics, indicating an understanding that these lessons compensate for deficits. P4’s response confirmed this understanding, feeling recognised by P2’s explanation. P4 emphasised how deeply these constructed differences have influenced their understanding of relationships between pupils, portraying themselves as a deficient dyslexic rather than just mentioning the additional lessons. They expressed a wish that ‘it will stop soon’, suggesting two interpretations. First, by hoping dyslexia will end, distancing themselves from the idea of dyslexia as an embodied deficit introduced by the additional lessons. Second, by linking the end of dyslexia with the end of additional lessons, implying that the special curriculum had caused the differences.

In sum, the empirical findings presented four main dilemmas (re)produced and reinforced by the renewed SEN assessment procedure. The next section discusses the four dilemmas with special focus on the teachers’ role within the inclusion assessment framework.

Manifesting the bureaucratic power and reducing inclusive pedagogy in and through the SEN assessment

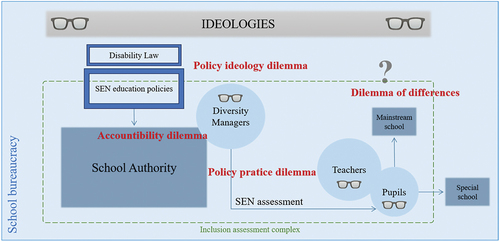

We structure this section as a discussion of the findings in terms of the Project Map (). Through our investigation of the inclusion assessment framework, we attempted to provide information about the management of pupils’ diversity and the construction of boundaries (Ydesen et al. Citation2022). In this way, the case study gave innovative insights into the teachers’ role in school bureaucracy.

First and foremost, we found that views of inclusion vary from exclusionary placement options (Ahrbeck Citation2016) in Austrian SEN schools, on one end of the scale, to community building (Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson Citation2006; Florian Citation2014), on the other. Which view is adopted depends on the teachers’ attitude towards both inclusion and disability. The latter view of inclusion is only implemented case by case in schools or the classroom, but not structurally across the school system. Placement of pupils in a special school, however, is not considered to be a form of inclusion, according to the international scientific debate and the international right to inclusive education (EASNIE, Citation2022; Göranson and Nilholm Citation2014). The variety of definitions leads to the dilemma of policy ideology within the inclusion assessment framework, which is illustrated by the conceptual and terminological confusion of participants of this study. At the macro level, the renewed Austrian policy legally defined inclusion as the placement of pupils based on the medical model of disability. Austrian policy has therefore strengthened the SEN discourse instead of following the international obligation to move national policies towards a broader view of inclusion. From a scientific standpoint, it is highly questionable whether the medical model of disability, as manifested in the SEN discourse, effectively addresses the policy ideology dilemma at the macro level. Indeed, our Situational Analysis points to the risk of reinforcing the dilemma at the meso and micro levels, as the teachers ‘experience public policies in realm that [might be] critical to [their] welfare and sense of community’ (Lipsky Citation1969, xii). In other words, teachers who advocate a broad view of inclusion and who are critical towards the SEN discourse are subject to an increased risk of suffering from mental ambiguity and imbalance. Interestingly, the Situational Analysis did not reveal any explicit criticism about the SEN policy reform per se. This is either because the data collection took place three years after the policy reform, or because feelings of reservation or mistrust influenced how the participants reviewed the reliability of state actors and authorities such as ourselves, who were representing the university.

The renewed SEN policy has the following general aims (1) to argue for an accountable and transparent process for tracking; (2) to emphasise that the SEN assessment is an ‘inherently neutral mechanism for segregating pupils into ability groupings for more effective teaching’; (3) to reduce the ‘pressure […] on the general system’ and legitimises ‘the “special unit” designed to respond to particularly intense client complaints’ (Lipsky Citation1969, 19 and 25). The bureaucratic reasoning behind these reforms has exacerbated the accountability dilemma, as both diversity managers and teachers experienced SEN assessment procedures to be ambivalent and opaque. The very inconclusiveness of these findings thus confirms previous research findings with regard to the establishment of standardised procedures and their transparency (Feyerer Citation2009, Grubisch Citation2011; Klicpera and; Gasteiger-Klicpera et al. Citation2023; Schwab et al. Citation2015). The bureaucratic developments within the last 20 years have shown that quantifiable instruments from disciplines such as medicine, psychology, economics, among others, have been preferred over pedagogical considerations due to neoliberal tendencies towards increased accountability. This in turn renders the question of pedagogy and thus teachers’ role in the context of the SEN assessment increasingly obsolete. Our case study has shown that the quality of pedagogy and inclusive approaches within SEN assessment highly depends on the autonomy and discretion exercised by the diversity managers, with very little involvement from teachers. Nevertheless, there is an essential difference between previous findings and those of this case study. Klicpera and Gasteiger-Klicpera et al. (Citation2023) suggested that the delay in the SEN assessment procedure is mainly caused by the parents’ disagreements with authorities, whereas our Situational Analysis identified the high bureaucratisation of the SEN assessment procedure as an unreliable process that introduces delays. We attribute the new insights to the fact that the renewed SEN policy has reinforced the top-down process and thus leads to a disenchantment with bureaucratic administration, especially among the teachers. At this point, it is highly questionable whether the implementation of the top-down process promotes school inclusion effectively. This problem goes beyond the bureaucratic decisions regarding pupils’ disability, curriculum, and placement, but fails to address pedagogical implications for inclusive education within the mainstream education discourse and practices on the ground.

Although the diversity managers are responsible for assessing the status of pupils in light of teachers’ grading, they do not have an active role in pedagogical practices on the ground. Their decisions on the SEN allocation, however, have far-reaching consequences for pupils’ educational careers and for teachers’ practices. The interconnections between the three constituting aspects of policymaking, administrative, and pedagogical practices within the inclusion assessment complex leads to a policy practice dilemma at the meso level. Teachers are dependent on the administrative decision-making of diversity managers even while they must use their pedagogical skills within the given structures of the mainstream school system. The constant deficits in financial, organisational, and staff resources speak of their dependency on managerial structures to the detriment of inclusion and pedagogical quality. Especially against the backdrop of current teacher shortages, teachers are exposed to the difficulty of teaching a high number of pupils, and being responsible to provide inclusive, high quality pedagogy for every pupil all the while protecting them from the possible threat of stigmatisation by the SEN label. These difficulties, in combination to their commitment to their profession, make teachers subject to the risk of overworking. Consequently, ‘teachers must attend to maintaining order and have less attention to learning activities’ (Lipsky Citation1969, 30). Considering the manifestation of bureaucratic enforcement power, it is highly questionable whether the SEN assessment effectively reduces the difficulties that teachers face or mitigates their risk of mental stress.

The last dilemma of difference, which manifests on the third step of the renewed SEN assessment (Norwich Citation2008), concerns both organisational and pedagogical practices at the meso level, as well as the ‘risks associated with stigma, devaluation, rejection or denial of opportunities’ (Norwich Citation2010, 116) at the micro levels. The perspective of pupils provided the important insight that pupils with and without SEN have internalised the label as marking a bodily and unchangeable deficiency, underlining previous international findings and the importance of considering pupils perspectives within assessment procedures (Knickenberg et al. Citation2020). The bureaucratically generated differences that result from the SEN label create boundaries between pupils that are (re)produced through the exclusionary and segregated school organisation in Austria. Therefore, it is highly questionable whether the SEN assessment reduces pupils’ internalisation of differences.

In sum, while the SEN assessment system is presented under the ideological umbrella of inclusion, it is, in truth, an organisation and administrative bureaucracy (Clark et al. Citation1999; Slee Citation2011) and thus an instrument for maintaining power, rather than an approach to promote pedagogy or inclusive education.

Conclusion, limitations, and outlook

The article researched the inclusion assessment framework with special focus on the role of teachers in Austria. The Situational Analysis found that the framework is a highly tensioned field that (re)produces several dilemmas with which teachers have to deal in their daily work. The policy ideology dilemma as well as the policy practice dilemma showed that these tensions are caused by the contradiction between the nationally renewed SEN policy and assessment practices, on the one hand, and ideology driven by inclusive education, legally binding due to international rights, on the other hand. The outlined difficulty makes teachers subject to the risk of mental stress in line with their professional commitment to providing inclusive education for every pupil. The accountability dilemma underlines that these tensions result from neoliberal tendencies to promote performance- and competence-based measurement. The renewed SEN policy intends to make school inclusion measurable through standardised SEN assessments that identify the disability, shape the curriculum, and guide the placement decisions. Simultaneously, the Situational Analysis has shown that pedagogy, especially inclusive pedagogy, and teachers do not play a significant role in SEN assessment procedures or derive pedagogical interventions from the SEN assessment. Rather, it rather reinforces the well-researched dilemma of differences, which pupils internalise due to administrative segregation and exclusion. In summary, the SEN policy reform has resulted in the reinforcement of bureaucratic power rather than involving teachers and pupils as active subjects of education and pedagogy.

The findings suggest various question for further research. Theoretically, there is a need to investigate the interplay between the various levels of the system, especially the connection between the macro and the micro levels. Special focus should be placed on the representation of pedagogical implications within policymaking. Empirically, it is of scientific interest to further investigate the teachers role in the light of their

– Pedagogical agency and professional ethos regarding inclusion under the enforcement of bureaucratic power.

– Coping strategies with regard to the identified difficulties within the inclusion assessment framework.

– Interactions between the school authority as a bureaucratic machine, and the pupils as subjects of inclusive education

– Use of administrative and pedagogical autonomy and discretion to implement inclusive education in a highly exclusionary and segregating school system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The paper is embedded in Erasmus+ Project I AM (Inclusive Assessment Map). The Project consists of the following participating European institutions: School Authority Board Vienna, Austria; University of Vienna, Austria; School of Education Porto, Portugal; University of Leipzig, Germany; Centre for Special Education, Belgium; Jönköping University, Sweden; UiT The Arctic University, Norway.

2. S1 was a former special school, which underwent a transformation process towards becoming an inclusive school from primary to secondary school with mixed-age classes. Schooling is project-based, with innovative methods and materials according to reformists such as Montessori among others. The pupil body consist of pupils with and without SEN. Mainstream teachers, special educators, assistance teachers, school psychologists, etc. build multiprofessional teams.

3. S2 is a mainstream primary school representing the Austrian standard. Schooling happens in a traditional way. The pupil body is heterogeneous, but pupils are not necessarily diagnosed. Teachers work with a class-size up to 25 pupils. Teaching does not happen collaboratively or in multiprofessional teams.

4. In the case of the pupils, the school principal acted as a gatekeeper. The teachers thus did not know which pupils had attended the focus group discussion, so as to prevent potential disadvantages for the pupils. As pupils are an especially vulnerable population due to their age and dependence on adults, our study required the provision of a sensitive procedure to comply with research ethics (Tangen Citation2008).

5. Each memo contributed to the illustration of the relationships between the codes according to the methodological categorisation of locating memos, bigger picture memos, and specification memos.

6. (1) The Unordered Map aims to collect all relevant aspects in a non-hierarchical manner to provide an overview of the situation. (2) The Ordered Map categorises the codes for the first time. (3) The Relational Map structures the research process by juxtaposing codes and categories, considering memo-writing results. (4) The Social Arena Map focuses on collective interdependencies, relationships, and the active and passive actors within the situation. (5) The Position Map highlights different stances within the research situation, facilitating the identification of emerging discourses. (6) The Project Map synthesises all cumulative findings by integrating empirical results and theoretical backgrounds.

7. The Position Map reveals the resourcing labelling dilemma, which is closely linked to and a sub-dilemma of the policy practice dilemma. We cannot elaborate further on it because the contribution attempt to map the inclusion assessment complex in a superordinated manner.

References

- Ahrbeck, B. 2016. Inklusion. Eine Kritik [Inclusion. A Critique. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Ainscow, M., T. Booth, and A. Dyson. 2006. Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. London: Routledge.

- Allman, D. 2013. “The Sociology of Social Inclusion.” Sage Open 3 (1): 215824401247195. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012471957.

- Ansperger, R., G. Wetzel, and J. Sauer. 1999. “Die Gutachtenerstellung im Rahmen des Feststellungsverfahrens zum Sonderpädagogischen Förderbedarf. Eine Analyse der Praxis in Österreich [The Preparation of Reports As Part of the Assessment Procedure for Special Educational Needs. An Analysis of Practice in Austria].” Heilpädagogik 42 (8): 8–17.

- Barbour, R. 2014. “Analysing Focus Groups.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis, edited by U. Flick, 313–327. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208956.

- Biewer, G., O. Koenig, G. Kremsner, L.-K. Möhlen, M. Proyer, S. Prummer, Resch, K., Steigmann, F., Subasi Singh, S. 2020. Evaluierung des Nationalen Aktionsplans Behinderung 2012–2020 [Evaluation of the National Action Plan Disability 2012–2020]. Vienna: Ministry for Social Affairs, Health, Care, and Consumerisum. https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/detail/o:1126770.

- BMWFW. 2023. “Sonderpädagogischer Förderbedarf”[ Special Educational Needs]. https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/Themen/schule/beratung/schulinfo/sonderpaedagogischer_fb.html.

- Buchner, T., and Proyer, M. (2020). “From special to inclusive education policies in Austria – developments and implications for schools and teacher education.” European Journal of Teacher Education 43 (1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1691992.

- Clark, C., A. Dyson, A. Millward, and S. Robson. 1999. “Theories of Inclusion, Theories of Schools: Deconstructing and Reconstructing the ‘Inclusive school’.” British Educational Research Journal 25 (2): 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192990250203.

- Clarke, A. E., C. Friese, and R. Washburn. 2022. Situational Analysis in Practice. Mapping Research with Grounded Theory. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003035923.

- EASNIE (European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education), Marcella Turner-Cmuchal, and Améie Lecheval, edited by. 2022. Legislative Definitions Around Learners’ Needs: A Snapshot of European Country Approaches. Odense, Denmark.

- Ebersold, S., and M. Cor. 2016. “Financing Inclusive Education: Policy Challenges, Issues and Trends.” In Implementing Inclusive Education: Issues in Bridging the Policy-Practice Gap, edited by A. Watkins and C. Meijer, 37–62. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620160000008004.

- Feyerer, E. 2009. “Ist Integration “normal“ geworden? [Is Integration the New Normal?].” Zeitschrift Für Inklusion 3. 2. https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion-online/article/view/162.

- Florian, L. 2014. “What Counts as Evidence of Inclusive Education?” European Journal of Special Needs Education 29 (3): 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.933551.

- Gasteiger-Klicpera, B., T. Buchner, E. Frank, R. Grubich, V. Hawelka, P. Hecht. 2023. Evaluierung der Vergabepraxis des sonderpädagogischen Förderbedarfs (SPF) in Österreich [Evaluation of the SEN assessment procedure in Austria]. Vienna: Ministry for Education, Sciences, and Research.

- Gitschthaler, M., J. Kast, R. Corazza Ruppert, and S. Schwab. 2021. “Resources for Inclusive Education in Austria: An Insight into the Perception of Teachers.” In Resourcing Inclusive Education, edited by J. Goldan and J. Lambrecht and T. Loreman, 67–88, Bingley, U.K: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Göranson, K., and C. Nilholm. 2014. “Conceptual Diversities and Empirical Shortcomings – a Critical Analysis of Research on Inclusive Education.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 29 (3): 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.933545.

- Grubich, R. 2011. “Zur schulischen Situation von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf (SPF) in Österreich – Analyse im Lichte der UN-Konvention über die Rechte von Menschen mit Behinderung [The school situation of children and adolescents with special educational needs (SEN) in Austria – An analysis in the light of the UN-Convention on the rights of people with disabilities].” Zeitschrift Für Inklusion 2. https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion-online/article/view/90.

- Hartmann, B., and M. Urban. 2011. “Qualitat Förderpadagogischer Gutachten [Quality in Special Education Needs Assessments].” Inklusion in bildungsinstitutionen. Eine Herausforderung an die Heil- und Sonderpädagogik [Inclusion in teaching institutions. Challenges to special pedagogy], edited by B. Lütje-Klose, M.-T. Langer, and B. Serke, 316–320. Bad Heilbrunn, Germany: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

- Klicpera, C., and B. Gasteiger- Klicpera-. 2006. “Erstellung von Gutachten über den sonderpädagogischen Förderbedarf: Ergebnisse einer Befragung der Bezirksschulräte und der Leiter der sonderpädagogischen Zentren in drei österreichischen Bundesländern. [Preparation of SEN assessment reports: results of a survey of school boards and heads of special education centers in three Austrian federal states.].” Heilpädogische Forschung Zeitschrift für Pädagogik und Psychologie der Behinderungen 30 (4): 198–209.

- Knickenberg, M., C. Zurbriggen, M. Venetz, S. Schwab, and M. Gebhardt. 2020. “Assessing Dimensions of Inclusion from students’ Perspective – Measurement Invariance Across Students with Learning Disabilities in Different Educational Settings.” Settings European Journal of Special Needs Education 35 (3): 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1646958.

- Krammer, M., M. Gebhardt, P. Rossmann, L. Paleczek, and B. Gasteiger-Klicpera. 2014. “On the Diagnosis of Learning Disabilities in the Austrian School System: Official Directions and the Diagnostic Process in Practice in Styria/Austria.” ALTER, European Journal of Disability Research 8 (1): 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2013.11.001.

- Lipsky, M. 1969. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. https://doi.org/10.7758/9781610447713.

- Nilholm, C. 2021. “Research About Inclusive Education in 2020 – How Can We Improve Our Theories in Order to Change Practice?” European Journal of Special Needs Education 36 (3): 358–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2020.1754547.

- Norwich, B. 2008. Dilemmas of Difference, Inclusion and Disability. International Perspectives and Future Directions. London: Routledge.

- Norwich, B. 2010. “Dilemmas of Difference, Curriculum and Disability: International Perspectives.” Comparative Education 46 (2): 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050061003775330.

- Oliver, M. (2013). “The social model of disability: thirty years on.” Disability & Society, 28(7), 1024–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.818773.

- Schädler, J., and Dorrance, C. (2012). “Barometer of Inclusive Education – Konzept methodisches Vorgehen und Zusammenfassung der Forschungsergebnisse ausgewählter europäischer Länder.” Zeitschrift für Inklusion (4). https://www.inklusion-online.net/index.php/inklusion-online/article/view/75.

- Schwab, S. (2020). Inclusive and Special Education in Europe. In S., Schwab (Ed.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1230.

- Schwab, S., M. G. P. Hessels, T. Obendrauf, M. C. Polanig, and L. Wölflingseder. 2015. “Assessing Special Educational Needs in Austria: Description of Labeling Practices and Their Evolution from 1996 to 2013.” Journal of Cognitive Education & Psychology 14 (3): 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.14.3.329.

- Seyda, S. S. 2020. Overrepresentation of Immigrants in Special Education: A Grounded Theory Study on the Case of Austria. Bad Heilbrunn: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

- Skrtic, T. M. 1991. Behind Special Education: A Critical Analysis of Professional Culture and School Organization. Denver, CO: Love Publishing.

- Slee, R. 2011. The Irregular School. London: Routledge.

- Statistik Austria. 2024. “Schulstatistik ab 2006.“ https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bildung/schulbesuch/schuelerinnen

- Tangen, R. 2008. ““Listening to children’s Voices in Educational Research: Some Theoretical and Methodological Problems.” “European Journal of Special Needs Education 23 (2): 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250801945956.

- Thomazet, S. 2009. “From Integration to Inclusive Education: Does Changing the Terms Improve Practice?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 13 (6): 553–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110801923476.

- Ydesen, C., A. L. Milner, T. Aderet-German, E. G. Caride, and Y. Ruan. 2022. Educational Assessment and Inclusive Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19004-9.