Abstract

Nephrotic syndrome due to secondary amyloidosis is not so common, and the prognosis depends on primary disease. We report a case of secondary amyloidosis caused by Takayasu's arteritis. Sustained high fever and acute renal failure proceeded to the occurrence of nephrotic syndrome. Secondary amyloidosis was diagnosed by renal biopsy before the diagnosis of primary disease. She was completely recovered from nephrotic syndrome after two years' treatment with prednisolone, aspirin, and dimethyl sulfoxide. This rare case provides meaningful suggestions for the diagnosis and treatment of acute renal failure and nephrotic syndrome caused by secondary amyloidosis.

BACKGROUND

Secondary nephrotic syndrome due to systemic diseases is very common.Citation[1] Systemic lupus erythematosus and diabetic nephropathy are main causes of secondary nephrotic syndrome. Amyloidosis is rare, especially as a primary disease of nephrotic syndrome,Citation[1] and any kind of chronic disease could cause secondary amyloidosis.Citation[2],Citation[3] We experienced a case who presented sustained high fever and subsequent acute renal failure (ARF). She was quickly recovered from ARF after six hemodialysis treatments. However, with the increase of urine volume, nephrotic syndrome appeared after the recovery from ARF. Renal biopsy revealed the presence of secondary amyloidosis, where the causative disease for ARF was different from that for nephrotic syndrome. We followed her for 10 years. We here report a suggestive case with ARF and subsequent nephrotic syndrome.

CASE REPORT

A 33-year-old woman presented to the Department of Gynecology in our hospital in February 1998, complaining of lower abdominal pain and high fever. She had a history of miscarriage and sustained high fever in August 1989, and had been treated with antibiotics and steroids for several months until an abdominal operation was performed. Although endometritis of the uterus was diagnosed at that time, low-grade fever had been occasionally observed.

After her admission in 1998, the administration of antibiotics did not improve her high fever. Anuria was noted from the second hospital day, and serum creatinine level was rapidly increased. She was diagnosed with acute renal failure and was referred to our ward. Her height was 150 cm and her weight was 48 kg, which was 4 kg greater than her usual weight. Body temperature was 38.8°C. Blood pressure was 114/50 mmHg, and there was no difference between the right and left arms. Sinus tachycardia of 102 /min was noted. Slight edema was found in eyelids but not in pre-tibia. Abdominal bruit was heard. Serum creatinine increased from 90 to 803 μmol/L (from 0.8 to 7.1 mg/dL) over three days. Blood urea nitrogen was 46.3 mg/dL, and serum sodium, potassium, and chloride concentration were 133, 4, and 100 mEq/L, respectively. She had an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 70 mm /first hour, C-reactive protein of 24.0 mg/dL, and total white cell count of 34.1 × 109/L. Her hemoglobin level was 10.1 g/dL and platelet count was 23.3 × 104/μL. Hemodialysis was started on her fourth hospital day (first hospital day in our ward). Serum immunoglobulin G, A, and M were 1650, 248, and 183 mg/dL, respectively (normal IgG, 870–1700; IgA, 110–410; and IgM, 33–190 mg/dL). Blood and urine culture was negative, and disseminated intravascular coagulation was not present. MPO-ANCA, PR3-ANCA, and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody were negative. Anti-nuclear antibody was 17 IU/L (normal, less than 12 IU/L), and anti-double- and single-strand DNA antibodies were 29 and 15 IU/L, respectively (normal, less than 12 and 15 IU/L, respectively). Serum amyloid-A protein was 15.5 μg/mL (normal, less than 8 μg/mL). After six hemodialysis treatments, her renal function quickly recovered, and urine volume was increased gradually. However, with the increase in urine volume, massive proteinuria (5–7 g/day), appeared, and she entered nephrotic syndrome.

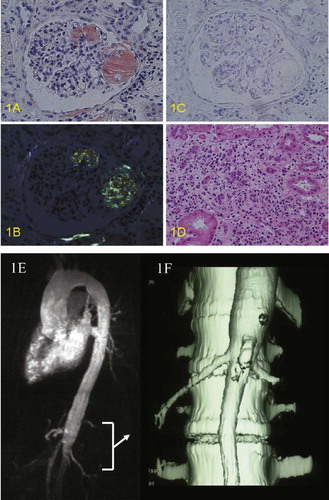

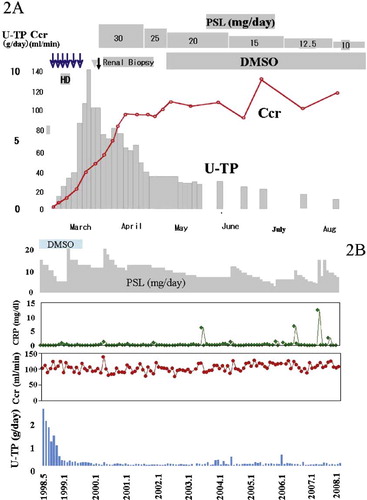

A percutaneous renal biopsy was performed on March 9, 1998. Acute interstitial nephritis and secondary amyloidosis (AA type) were diagnosed (see –). Secondary amyloidosis was confirmed by the biopsy specimen from the stomach. Collagen disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus was initially considered as her primary disease. However, anti-nuclear antibody and anti-double strand DNA antibody were too low to cause sustained high fever, and facial erythema was not found. To examine the primary disease, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and three-dimensional computed tomography (3D-CT) were performed. The narrowing of the lower abdominal aorta distal to the renal arteries was noted (see and ). Finally, she was diagnosed with Takayasu's arteritis and secondary amyloidosis. Treatment with prednisolone (30 mg/day) and heparin (4000 u/day) was started three days after the renal biopsy, and C-reactive protein became 0.08 mg/dL after two weeks. Her proteinuria decreased gradually. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) ointment (5 mL/day) was added in August 1998 and continued until June 2000 (see ). Two years later, she had completely recovered from the nephrotic syndrome. During the subsequent eight years, proteinuria was not observed, and her renal function was normal. Her current serum creatinine and daily urinary protein excretion were 0.67 mg/dL and 0.02 g/day, respectively. However, at least 5–10 mg prednisolone was required to suppress Takayasu's arteritis. Her long-term clinical course is summarized in .

Figure 1. Renal biopsy specimens: (A) Congo-Red staining, (B) Congo-Red staining with polarization filter, (C) Congo-red staining after KMnO4 treatment, (D) HE staining, and (E,F) magnetic resonance angiography. (A,B) Congo-red positive lesions were seen in glomeruli and vascular walls. (C) These lesions were KMnO4 non-resistant (AA type). (D) Severe interstitial nephritis was also noted. Magnetic resonance angiography (1E) revealed the narrowing of the lower abdominal aorta distal to the renal artery. Renal arteries were not involved in her Takayasu's arteritis. 3D-CT (1F) confirmed the stenosis of the abdominal aorta but not the renal arteries.

Figure 2. Short- and long-term clinical course of the case. (A) Nephrotic syndrome appeared after recovery from acute renal failure. The administration of prednisolone gradually decreased proteinuria. The ointment of DMSO further decreased proteinuria. (B) Proteinuria disappeared after two years' treatment with prednisolone, DMSO, and aspirin; however, 5–10 mg prednisolone was required to suppress Takayasu's arteritis. Abbreviations: U-TP = urinary protein excretion, Ccr = creatinine clearance, CRP = c-reactive protein, PSL = prednisolone.

DISCUSSION

The patient's sustained high fever had suggested a presence of chronic infection or collagen disease. Before her primary disease was found, she was diagnosed as secondary amyloidosis. Takayasu's arteritis is not a rare disease and sometimes causes nephrotic syndrome by secondary amyloidosis.Citation[4] However, secondary amyloidosis is a rare cause of nephrotic syndrome.Citation[1] Acute renal failure was caused by acute interstitial nephritis in this case. A gallium scintigram also showed high uptake by both kidneys. Secondary amyloidosis sometimes causes interstitial nephritis and acute renal failure.Citation[5] Long-lasting secondary amyloidosis usually results in a gradual decline of renal function partly by interstitial nephritis. She recovered quickly from acute interstitial nephritis and acute renal failure, but the recovery from secondary amyloidosis required two years, suggesting that interstitial nephritis and acute renal failure are not caused by secondary amyloidosis. Nephrotic syndrome sometimes causes acute renal failure mainly by hypovolemia.Citation[6],Citation[7] The average length of time between the onset of nephrotic syndrome and subsequent acute renal failure is four weeks.Citation[7] However, in this case, acute renal failure occurred before the appearance of nephrotic syndrome. MRA and 3D-CT showed that renal artery stenosis was not present. It is possible that administered antibiotics, NSAIDs, other drugs, or deterioration of Takayasu's arteritis may have caused acute interstitial nephritis. Her miscarriage may have been caused by Takayasu's arteritis. She has been treated with steroids, heparin (later by aspirin), and DMSO ointment. Because her Takayasu's arteritis has been stabilized, secondary amyloidosis and subsequent nephrotic syndrome have been completely improved. The complete recovery from nephrotic syndrome suggests the disappearance of amyloid deposition from the kidney, although renal biopsy was not performed after the recovery from secondary amyloidosis. In this case, the secondary disease was diagnosed before the primary disease, and the acute renal failure made her disease complicated. Although secondary amyloidosis is a rare cause of nephrotic syndrome, any kinds of chronic diseases may cause secondary amyloidosis. Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common primary disease for secondary amyloidosis. The decrease in renal function and the occurrence of nephrotic syndrome in patients with rheumatoid arthritis suggest the occurrence of secondary amyloidosis. Renal biopsy should be performed at least once during clinical course of nephrotic syndrome to examine the causative disease.

In summary, we here report a case with Takayasu's arteritis and subsequent secondary amyloidosis-induced nephrotic syndrome and simultaneous interstitial nephritis-induced ARF. Secondary amyloidosis should be taken into account as a causative disease for nephrotic syndrome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (19590955, 19590957, and 18590895).

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- Orth SR, Ritz E. The nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2001; 338: 1202–1211

- Gertz MA, Kyle RA. Secondary systemic amyloidosis: Response and survival in 64 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991; 70(4)246–256

- Lachmann HJ, Goodman HJB, Gilbertson JA, Gallimore JR, Sabin CA, Gillmore JD, Hawkins PN. Natural history and outcome in systemic AA amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356: 2361–2371

- Numano F, Okawara M, Inomata H, Kobayashi Y. Takayasu's arteritis. Lancet. 2000; 356: 1023–1025

- Tovbin D, Kachko L, Hilzenrat N. Severe interstitial nephritis in a patient with renal amyloidosis and exacerbation of Crohn's disease. Clin Nephrol. 2000; 53: 147–151

- Loghman-Adham M, Siegler RL, Pysher T.J. Acute renal failure in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Clin Nephrol. 1997; 47: 76–80

- Smith JD, Hayslett JP. Reversible renal failure in the nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992; 3: 201–213